10,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Parkstone International

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

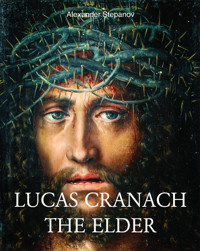

Lucas Cranach (1472-1553) was one of the greatest artists of the Renaissance, as shown by the diversity of his artistic interests as well as his awareness of the social and political events of this time. He developed a number of painting techniques which were afterwards used by several generations of artists. His somewhat mannered style and spending palette are easily recognized in numerous portraits of monarchs, cardinals, courtiers and their ladies, religious reformers, humanists and philosophers. A part of the Great Painters Collection, translated from the Russian by Paul Williams. 109 full color plates and numerous black and white and two-color illustrations interspersed by text. Includes a chronological table of the work of Cranach and his notable contemporaries.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 125

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Author: Alexander Stepanov

© Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

© Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Image-Bar www.image-bar.com

ISBN: 978-1-64699-964-4

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers, artists, heirs or estates. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

Alexander Stepanov

Lucas Cranach

Contents

His Life

His Work

Biography

Index

Notes

His Life

At Epiphany, 6 January 1508 the artist named Lucas from the town of Kronach, then in Nuremberg in the retinue of Frederick the Wise, Elector of Saxony, was granted the right to bear arms by his royal patron. The patent specified: “A yellow shield bearing a black serpent with black bat’s wings in the middle, on its head a red crown and in its jaws a gold ring with a ruby stone; on the shield a helmet with a black and yellow coil, and on the helmet a heap of blackthorn, over which there is a servant of the same kind as on the shield”. A surviving copy of a drawing made by Lucas fits this description very well, apart from the fact that the dragon is light-coloured and its wings shine out against the dark ground of the shield, while the thornless blackthorn might be taken for brushwood. This dragon became Lucas’s device. He used it to sign his works, sometimes adding the monogram LC. The dragon above a heap of brushwood on the coat-of-arms looks like smoke and flame; in the paintings it is a living fire, persuading all who see it that it is Cranach. The mercurial, life-affirming sign of the dragon accorded with the artist’s own perception of himself. Otherwise, why bother to include those fine curves and membranous wings, the fabulous crown and ruby ring in hundreds of works? It would have been far easier to use just the monogram.

The coat-of-arms which Lucas happily adopted could only have been devised, at the elector’s instigation, within the small circle of people who knew the artist well and knew how to express their ideas in the esoteric language of heraldry. In 1502 Frederick founded a university in Wittenberg, the royal Saxon residence situated halfway between Leipzig and Berlin. Drawn by the magnanimity, tolerance, intelligence, broad interests and generosity of the elector, the “knight errant” of the scholarly world began to collect there: admirers and experts on ancient literature and philosophy, lawyers, natural scientists, physicians, theologians, mathematicians, alchemists and astrologers - in short, many of those whom we now collectively call humanists, who had not managed to find a place for themselves at other centres of learning less positively inclined towards free-thinking. At Frederick’s court humanist enlightenment ran along with the traditions of the knightly era: the service of one’s chosen lady, single combat at tournaments, the extravagant royal hunt and noisy feasts. The old science of heraldry was undergoing a revival due to the erudition of the humanists.

Since Cranach was a respected figure among the scholars and intelligent courtiers in a place where everyone was on close terms with everyone else (inevitably as the whole “city” numbered only 400 households and a couple of thousand inhabitants), the artist may himself have been involved in creating his own coat-of-arms. The twists and turns of the dragon’s body are similar to the lightning-like zigzag which Cranach used to sign an engraving in 1502. It is an illusion to Cranach’s fiery, impetuous character.

1. Golgotha, before 1502. Oil on beech, 59 x 45 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

2. St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata, c. 1502. Oil on pinewood, 86.8 x 47.5 cm. Akademie der Bildenden Künste, Gemäldegalerie, Vienna.

3. St. Jerome in Penitence, 1502. Oil on limewood, 56 x 42 cm. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

4. Portrait of Dr Johannes Cuspinian, c. 1502. Oil on wood, 60 x 45 cm. Oskar Reinhart Collection ‘Am Römerholz’, Winterthur.

5. Portrait of Anna Cuspinian, 1502. Oil on wood, 60 x 45 cm. Oskar Reinhart Collection ‘Am Römerholz’, Winterthur.

At the same time, the dragon as an alchemic symbol for fire, the changeable element that brings about transformations is a metaphor for creativity. It is in fire that the gold ring set with a ruby is born. The artist, like the alchemist, creates beautiful forms with the fire of creativity. The dragon breathes fire and is fire-like in its shape, movements and greed. It soars into the air, yet lives below the ground or in the depths of the waters, thus symbolizing the unity of the four elements. In the same way Cranach’s art embraced the whole of nature. Lucas’s dragon wears a crown. The German for “crown” is Krone, which is phonetically linked with Kronach, Lucas’s birthplace. It also means that Cranach is a monarch in his profession. Wherever we come across the crowned dragon, it tells us with all its appearance: “I was placed here by crafty Lucas from Kronach, an artist who enjoys life and is given to inconstancy and mockery.

In his work he is jealous, fast and indomitable. His art is all-embracing, ingenious, wondrous and mysterious.” When Lucas acquired his coat-of-arms, he was in his thirty-sixth year, a little short of halfway through his long life. We know that he included a self-portrait in the painting, The Holy Kinship, produced three years later on the occasion of his own marriage. In the painting he is the husband of the sister of the Virgin Mary, and, in a personal, everyday sense, the head of the family. From that moment on, he possessed the right to set up a studio and could earn his daily bread, relying only on his own skill and God’s mercy. He humbly donated the painting to one of the churches in Wittenberg, but it was the gift of a man aware of the greatness of his talent. In the humanist circle, whose moods and opinions Lucas heeded, it was customary to consider talented people melancholic. However, that particular affectation expresses itself only perhaps in the fact that the character in the painting is wrapping himself in his gloomy cape.

It is as if he, a Wittenberg “Childe Harold” of the early sixteenth century, finds it uncomfortably cold in a room where his female relatives are wearing low-necked dresses and the children nothing at all! In the facial expression, humanist fashion gives way to the direct presentation of the soul. The artist looks out at the viewer, but his spirit is looking to the future. Concern over the worthy fulfilment of his earthly vocation and hope for the salvation of his soul fuse in a gaze that challenges fate. Lucas still did not know that he would become one of Wittenberg’s richest burghers, a member of the city council, treasurer, burgomaster and friend of the prince. Yet in the golden-yellow robe turned into burning tongues by the black slits, in the elusive transformation of locks of hair into a translucent plume and the fiery festoons of the headdress, in the secretive, insinuating manner there is something which links the figure with the yellow, black and red dragon device. This is a man who will not deviate from the course preordained by his coat-of-arms. The first thirty years of his life are cloaked in obscurity. He probably learnt his trade from his father who was known as Hans Maler - Hans the Painter. In about 1502 this young provincial turned up in Vienna, the residence of the Habsburg rulers.

6. Portrait of a Lawyer, 1503. Oil on softwood, 54 x 39 cm. Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg.

7. Lamentation Beneath the Cross, 1503. Oil on pine, 138 x 99 cm. Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

8. The Crucifixion, 1506-1520. Oil on panel, 67 x 46.5 cm. Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen.

By that time the efforts and interests of Emperor Maximilian I had turned the University of Vienna into one of the greatest humanist centres. Among the rising stars in the humanist firmament of the imperial capital was Johannes Cuspinian. A poet crowned with laurels by the Emperor, a historiographer and outstanding physician, Cuspinian became rector of the university at the age of twenty-seven, then its chief administrator, and in 1502 the Dean of the Medical Faculty. He was the same age as Cranach and from the same part of the world. Was that not perhaps why the young artist decided to try his luck in Vienna?

He can hardly have been moved by strong humanist inclinations, though. It was more likely a question of his reckoning on commissions from the teaching staff of the university, book publishers, the rich religious houses of the capital and, with luck, the court itself. Vienna was the place where Lucas’s earliest surviving works were created, including Calvary, St. Francis Receiving the Stigmata and St. Stephen. They are very different, and Lucas’s talent had many facets. In trying to recreate the hour of Christ’s death, Lucas felt himself to be a living witness, overflowing with heart-rending impressions and prepared to depict everything in an unvarnished manner.

But Lucas the painter saw everything primarily as an occasion to work with colour. The two were unable to find a common tongue. The person missing here is “Lucas the director”: he would have convinced the witness that not everything in the painting was of equal importance and would have reined in the painter’s fascination with colour where it was inappropriate. In that event, perhaps, the witness would not have placed a dog gnawing human remains in the foreground and the painter would not have been carried away by the rivulets of blood running down to the foot of the cross. If the lower half of the painting is covered, one’s heart feels the saviour’s agony and hears that last cry like a hand raised up to Heaven: “My God, my God. Why hast thou forsaken me?”

But looking at the cavalcade of tormenters, one forgets about their victim, such is the power of the enchanting play of colours around the white horse with a silver mane. St. Francis was painted by an artist who knew how to subordinate all means to a single end. The Franciscans who commissioned the work probably had a very ambivalent attitude to the sentimental legend of their altruistic founder, St. Francis, who lived in almost pagan harmony with nature, blessing it, preaching to the birds and calling the sun, the moon, fire and water nothing less than a “brother” or “sister”. Lucas was supposed to depict the saint as an ascetic whose tireless struggle with worldly temptations reached its apogee near the summit of Mount Alverna, when, striving with all his soul to Christ brought Francis a vision of the crucifixion inspired by a seraph, and his body became marked with the same wounds as the saviour. Lucas rejected the tradition that the saint’s noble origin and spiritual purity should be stressed by a fine physique and regular features. His Francis of Assisi is huge, with a low forehead, prominent cheekbones, heavy arms, and weather-beaten skin. It seems that anyone who dared to approach him would be reduced to ashes by his love of God. The snow-capped peaks in the distance are like a piece of ice in a hot palm. The mirror surface of the water is like untroubled sleep after a sleepless night; the calm sky like a fine day after a storm. But the saint in his mystical frenzy does not see the mountains, the water or the sky. On the other hand, the artist did see, and reverentially recreated the chaste charm of nature which knows neither sin nor repentance and stands ready to console the sufferer.

9. Saint George, 1506. Woodcut, 37.8 x 27.5 cm. Ursula and R. Stanley Johnson Collection.

10. The Beheading of St. John the Baptist, c. 1509. Engraving on wood, 40.1 x 27.7 cm.

11. St. John Chrysostome in Penitance, 1509. Copper engraving, 25.5 x 20 cm. The Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg.

12. The Sacrifice of Marc Curtius, c. 1506-1507. Woodcut, 33.5 x 23.5 cm. C.G. Boerner Collection, Dusseldorf.

13. The Altarpiece of the Holy Kinship or Totgau, 1509. Tempera and oil on lime, central panel, 121 x 100 cm. Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt.

14. The Rest on the Flight into Egypt, 1504. Oil on wood, 70.7 x 53 cm. Staatliche Museen, Gemäldegalerie, Berlin-Dahlem.

The tree repeats the agonized twist of the saint’s body and tenderly touches his halo with its leaves. While he paid tribute to Francis’s self-abnegation, Lucas was nonetheless spiritually closer to the saint’s unspecified companion who has settled down against a hillock with a blithe smile on his face. The woodcut of St. Stephen may have been used to produce individual prints which circulated separately, but it was mainly intended as an illustration for a service book. It was usual practice at the time to tint such illustrations with watercolour. Stephen was the first Christian martyr stoned to death by a crowd at the instigation of the pharisees. Today we can point in the woodcut to a strange juxtaposition of the tragic and the amusing. The martyr with his terrible burden has humbly bowed his head beneath trees which have grown together with all sorts of evil creatures.

Acorns grow alternately with grapes on the trees while two mischievous putti have settled on their tops and play a drum and a pipe. The music suggested is lively, martial, and the coiling monsters might amuse but they do not frighten - the knotted ears of one of them alone are worth a fortune!

This strong grotesque element came into Lucas’s work from the traditional decoration of manuscripts, where the margins were adorned with ornamental designs teeming with all manner of real and imaginary plants and creatures. The figure of Stephen seems to have been cut from a mighty tree trunk. Lucas revelled in the combination of various types of line and stroke with which he conveys the density of fabrics, the hardness of stones and the softness of hair. He drew with relish all that was twisting, turning and pulsating with the mysterious currents of life, everything akin by nature to the dragon. These early works already indicate an artist who dared to testify truthfully about dreadful things and who possessed a good-natured sense of humour; an artist capable of expressing the impulses of the human soul, and of showing his human subject as a restless particle in the infinite realm of nature.

It was these qualities in Lucas that won over Cuspinian who became his friend, and commissioned a wedding portrait from him on the occasion of his own nuptials. Johannes and his bride, Anna, sit on the grass beneath the canopy of two trees whose branches most probably interlace somewhere far above their heads. The young people have only to stretch out their hands to touch each other. Reflecting on the aphorism, he has just read in a book, the famous professor raises his gaze pensively and spots above Anna a falcon that has taken a heron. His cheeks redden, a gust of air causes his golden curls to fluff out and the barely noticeable shadow of a smile plays across his face. The sixteen-year-old Anna sees nothing of this. Scowling childishly, she waits for the moment when her scholar bridegroom will come down from the clouds. Her fingers pluck nervously at a carnation, a symbol of fidelity, while her heart burns like fire blazing in the distance. And so they communicate with each other, silently and passionately.

15. Venus and Cupid, 1509. Oil on canvas, 213 x 102 cm. The Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg.

16.