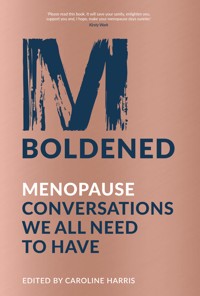

It's time to change the global menopause conversation. Let's stop talking just in terms of the stereotyped sweaty, hot-flush beleaguered female, the infertile crone or the wise woman – the reality of the menopause experience is so diverse and deserves to be heard. M-Boldened: Menopause Conversations We All Need to Have is a book about menopause unlike any other. Its contributors, speaking from many different walks of life, open up the conversation in new and profound ways for people across the globe. Recognising menopause as a human rights issue that affects everyone everywhere, these 21 chapters cover an astounding range of perspectives, from harrowing experiences of surgical menopause, the impact on relationships and hormonal realities of transitioning, to revelations of shocking neglect in the UK criminal justice system and compelling chapters on menopause as a time of activism, rage, reawakening, transformation and realising your own power. The honesty, intimacy and passion shared in these pages will make you see menopause in a whole new light. Each chapter shapes a much-needed courageous conversation about how we can and should view menopause and midlife. Read on to be part of the new conversation.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 533

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2020

FLINT is an imprint of The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.flintbooks.co.uk

© Flint Books, an imprint of The History Press, 2020

With the following exceptions where individuals have granted the Publisher the exclusive license to publish material for a set term, but have retained the copyright in their own individual contributions as follows:

© Chapter 5: Sophia Tzeng, 2020

© Chapter 8: Carren Strock, 2020

© Chapter 9: Lee Hurley, 2020

© Chapter 12: Emily Steinberg, 2020

© Chapter 14: The Medical Women’s International Association, 2020

© Chapter 15: Caryn Franklin, 2020

© Chapter 16: Arzu Qaderi, Diba Naikpay, Noorjahan Akbar, Mawloda Tamana Nazari, 2020

Each individual contributor has retained the moral right to be identified as Author of their own contribution in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The moral right of Caroline Harris to be identified as General Editor of the whole work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

General Editor: Caroline Harris

Consultant Editor: Jo de Vries

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9639 6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Praise for M-Boldened

Introduction: Beginning to Break the Silence by Caroline Harris

Chapter 1: It’s Time to Make ‘Normal’ Visible

Compassion in Politics founder and bestselling author of WE: A Manifesto for Women Everywhere, Jennifer Nadel explores how the menopause turned her life upside down and set her out on a new path

Chapter 2: Menopause: A Human Rights Issue

Dr Padmini Murthy, Global Health Lead of the American Medical Women’s Association and First Vice President of the Global NGO Executive Committee associated with the Department of Global Communications to the United Nations, argues that understanding and awareness of menopause needs to be viewed as a fundamental human right

Chapter 3: Making Menopause Matter

Activist and founder of the groundbreaking #MakeMenopauseMatter campaign and not-for-profit organisation Menopause Support, Diane Danzebrink offers a compelling account of how menopause awareness is vital for a healthy society

Chapter 4: Reflections on a Period of Change

Acclaimed screenwriter Carol Russell, whose screen credits include writing for the BAFTA 2020 nominated series Soon Gone: A Windrush Chronicle and being part of the BAFTA-winning team behind The Story of Tracy Beaker, explores how her own menopause experiences inspired her to champion midlife representation on screen and in life

Chapter 5: From Menarche to Menopause: A Mother’s Journey

Sophia Tzeng, entrepreneur and non-profit executive, reflects upon the periodicity of her life as she charts the journey from her first period through to menopause and how her own experiences have helped shape her conversations with her daughters, who include Nadya Okamoto, founder of Period. The Menstrual Movement

Chapter 6: Pakistan: Where There Are No Words

Shad Begum, recipient of the International Women of Courage Award for her pioneering work in Pakistan, asks how women can begin to have a conversation about something for which there is no word in places where women’s health has been underprioritised for so long

Chapter 7: In This Together

Sophie Watkins, menopause blogger and co-host of ‘The Good, the Bad and the Downright Sweaty’ podcast, and her fiancé Stephen Purvis talk with moving honesty about how Sophie’s surgical menopause, due to endometriosis and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), affected them and their lives

Chapter 8: A Time of Letting the Baggage Go

Carren Strock describes herself as an all-round Renaissance Woman, and as a writer she is probably best known for her groundbreaking book Married Women Who Love Women, now in its third edition. Hers is an exploration of how menopause can be a time of release, renewal and rediscovery

Chapter 9: Menopause and Transition

Journalist and freelance writer Lee Hurley discusses the shock of his journey into menopause as a trans man and explores what menopause means as you move through the landscape of gender, relationships, sex and parenthood

Chapter 10: A Cellular Experience

Writer Clare Barstow explores how her time in prison exposed her to the harrowing lack of provision for and understanding of women’s health in the UK criminal justice system. Her experiences shed light on an often neglected area of menopause care

Chapter 11: A Flâneuse of This Sickness

Cat Chong is a poet in their twenties, who is also a PhD student in Medical Humanities at Nanyang Technological University (NTU) in Singapore. They explores how we use language to frame the menopause and reflects in conversation on society’s difficult relationship with the female body from a non-binary perspective

Chapter 12: Men O Pause

Acclaimed graphic narrative artist, painter and fine art educator Emily Steinberg visualises the grim history of menopause, from the Salem Witch Trials and nineteenth-century treatments for hysteria to the medical menopause of the twenty-first century, ending with her own positive experience of empowerment and self-actualisation

Chapter 13: Making the M-Word Go Viral

Aisling Grimley, founder of the hugely successful online community My Second Spring, and Ireland’s first menopause coach Catherine O’Keeffe (Wellness Warrior.ie) explore the mystery of perimenopause and the power of sharing our experiences and knowledge

Chapter 14: Menopause Is Global

The Medical Women’s International Association (MWIA) offers an insight into menopause across the world, including contributions from doctors and practitioners in North America, Italy and Nigeria

Chapter 15: An Act of Renaming and Reclaiming

Journalist and broadcaster Caryn Franklin looks at how we can address society’s unrealistic obsession with youth and negative projections of the maturing feminine appearance by reframing the postmenopause picture

Chapter 16: Our Unspoken Needs: The Women of Afghanistan

Award-winning filmmaker, presenter and activist Arzu Qaderi has filmed and interviewed women throughout Afghanistan about their lives, and uses this to give voice to what is for many the unspoken topic of menopause and women’s health

Chapter 17: Nursing the Menopause

2020 is the International Year of the Nurse and Midwife – in honour of this, the Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation brings together voices from across its membership to reflect on their own and their patients’ experiences of menopause

Chapter 18: Demystifying the Menopause: The Research, Medicine and Education We All Need

Dr Wen Shen, Assistant Professor in the Johns Hopkins Medicine Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Baltimore, and Dr Christine Ekechi, Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist at Imperial Healthcare NHS Trust, London, share their specialist expertise in treating women throughout their lives and their passionate advocacy for better menopause health education

Chapter 19: Becoming Wise Women

Lynne Franks, communications powerhouse, founder of the SEED women’s empowerment network and author of the globally renowned The SEED Handbook, on sustainable enterprise with feminine values, champions how women can harness their innate wisdom and power as they age

Chapter 20: The Menopause Café Story and Conversations

The Menopause Café, founded by Rachel Weiss, is a safe, open space for everyone to explore what menopause means to them, regardless of gender or age. Rachel shares her inspiration and vision for the movement, followed by a series of real Menopause Café conversations

Chapter 21: Loving Life Now

Olympic gold-medal-winning athlete, first Black woman to win gold for Great Britain, first woman Vice Chair of Sport England and Patron of Adoption UK, Tessa Sanderson CBE explores how her attitudes to health, exercise and family helped her through the menopause

Acknowledgements

Menopause Literacy and Sources of Support and Information

Praise for M-Boldened

‘Please read this book. It will save your sanity, enlighten you, support you and, I hope, make your menopause days sunnier.’

Kirsty Wark FRSE, award-winning BBC journalist andNewsnightpresenter

‘It’s thanks to women and conversations like these that the story of menopause as something to dread and suffer is changing to something to embrace and thrive through.’

Clare McKenna, acclaimed Irish radio and TV presenter and broadcaster

‘A powerful book that captures some raw truths and unique stories of menopause from woman across the globe. Thank you to Caroline Harris for her outstanding work on producing M-Boldened, a must read and a book that has the power to both unite and empower woman of all generations.’

Australian Nursing and Midwifery Federation

‘Menopause is a natural process to ageing but unfortunately due to cultural barriers many women in the traditional societies hide this change. On top of that due to a lesser focus on women’s own health, a large number of women have no knowledge about the effects of menopause on their emotions and health. I hope this scholarship will be a great effort to help women to get answers to unsolved questions.’

Rukhshanda Naz, the first woman Ombudsperson-KP for the Protection of Women against Harassment at Workplace, activist and lawyer, previously Head of UN Women Pakistan’s Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa/Federally Administered Tribal Areas division

‘This is a book that every woman needs to read. Unabashedly truthful and real. I’m so happy this discussion has finally started!’

Laura Dowling BSc(Pharm) MPSI, The Fabulous Pharmacist (@fabulouspharmacist)

‘The subject of menopause is very serious because this natural state which is part of the normal sexual and reproductive life of women is often negatively treated by harmful traditional behaviors [sic]. Postmenopausal women are thus excluded from sexual relations, including with their husbands, on the grounds that it would cause illnesses in them. One of the consequences of this practice is that all pathological bleeding, including that caused by cancer of the uterus, is paradoxically welcomed by victims who believe they are having a return to menstruation. In my long struggle against female genital mutilation, child marriage, and other harmful traditional practices, I have always spoken out against the harmful traditional practices including those associated with menopause. This is why I am very happy to see that renowned and very committed specialists like yourself [in reference to Dr Eleanor Nwadinobi, see Chapter 14] have participated in the in-depth analysis of the phenomenon of menopause through this excellent book entitled: M-Boldened: Menopause Conversations We All Need To Have, edited by Caroline Harris.’

Dr Morissanda Kouyaté, Executive Director of Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices; laureate of the 2020 United Nations Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela Prize

Introduction

Beginning to Break the Silence

Strangely, I can’t remember what age I was when my periods started, but I do remember the emotion that accompanied them: rage.

Rage at this uncalled-for transformation of my body. Rage at the lack of control; that I was no longer the person I had become accustomed to being; the remoulding of what and who I was and how I would be seen. Rage that I might bleed at any time (my periods were irregular for the first few years); that I would be ‘caught out’. Rage, too, at becoming a woman – something that, from what I had picked up during childhood and early teens, and parts of my own family history, seemed a limiting, perhaps even dangerous, thing to be.

At the other end of my oestrogen lifespan, in 2015, rage was again my overriding and defining emotion. I was outraged not so much by the hot flushes (I used to suffer from chronic panic attacks, which for me were a considerably more horrible experience); not so much by the grief of my fertility ending (I had miscarried trying for a second child some years before and so had already faced losing my reproductive ability). It was more about the sensuality and embodiment of menopause: about sex, arousal, the forest architecture of my vagina and, particularly, how I smelled.

This may sound trivial, especially to those whose experience of menopause has been much more physically and psychologically challenging than mine, but for me, it struck at the heart of those feelings of lost control and of my body suddenly becoming another country. My geography – my ecosystem – was changing, and I was a stranger to myself in this strange land. I no longer got wet with desire when I expected to. My scent, when I explored, was not the soft fragrance I had known; instead, as I grappled with trying to pin down and name it, all I could think of was bitter seaweed and burnt rubber. Before menopause, my body was my ‘familiar’ and I felt comfortable with it, even in its ageing (well, most of the time, anyway). I had adapted to the changes that come after giving birth, and the anxieties that those transformations can bring. But this was something else. Somewhere else. And I didn’t like it.

As I navigated through the physiological upheavals – like many others on the same journey, gathering information via the internet, and the occasional conversation with one or two friends – I was gripped by a different kind of anger. Why wasn’t any of this being talked about? Why had I arrived at menopause so unprepared? Why had I not previously been made aware of any symptoms apart from hot flushes? The rhetoric of menopause seemed to be either silence or joke. And as much as humour can be essential in weathering both the absurdities of life and the particular difficulties we each face, all too often the ‘jokification’ of menopause is belittling, uncomfortable and barbed.

As I looked further, I began to unearth books and articles, from the feminist-inspired Our Bodies, Ourselves series, which arose from the Boston Women’s Health Collective in the 1970s with its aims of empowering women through increased health awareness, to Gail Sheehy’s The Silent Passage, first published in the early 1990s. In the original Vanity Fair article that laid the ground for her book, Sheehy referred to menopause as ‘the last taboo, the stigma of stigmas’. This was more than twenty-five years ago; so why does it still feel bold and exposing to speak up publicly about menopause? Why can it still feel for so many of us as though we are making our way through this transition on our own, when it is something that will affect half the world’s population who attain this stage of their lives?

I wanted to explore these questions: about what menopause is, and what it means not only individually, but in our wider societies. I wanted to hear from other people about their own experiences, knowledge and understandings, not only from my own position in the UK, but globally.

What is menopause?

The word ‘menopause’ is a relatively recent term, but in these times of cultural globalisation and tech-speak, it has established itself as the modern way to refer to this life transition. Coming from the ancient Greek via Latin, ‘meno’ means ‘month’ and through this the menses: women’s ‘monthlies’ or periods; ‘pause’ is here an ‘end’ or ‘stop’, rather than a brief interlude. As a medical term, menopause was coined by a French doctor in 1821, according to sociologist Cécile Charlap, author of La Fabrique de la Ménopause (which can be translated as The Construction of the Menopause). From here it passed into the English language through the dialogue of nineteenth-century doctors discussing their surgical experiments on women (Emily Steinberg’s ‘Men O Pause’ chapter, which relates some of this history, is a graphic account in more than one sense). ‘Menopause’ was first used in print in 1872 and became increasingly common during the twentieth century. Charlap notes that ‘climacteric’, more common today in the US, has a much longer history in this context: ‘Inherited from antiquity, [it] was used to qualify this critical turning point in human ageing, thus not at all specific to women nor focused on the end of menstruation and fertility,’ she explained in an interview with Sandrine Hagège for the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS). ‘The change’ – the phrase my mother used to speak of her midlife in the late 1970s – today has mixed connotations; it may be seen as outmoded and related to old-fashioned ideas and stereotypes, and thus derogatory, but at the same time can offer a non-medicalised way of talking about transition.

Most people in the twenty-first-century West are used to viewing menopause through the lens of medical categorisations and processes: a language of symptoms, diagnoses, deficiencies, treatments, replacements. We list those we have, those we don’t. Those we’ve tried, those we won’t. Such naming can be an important step in understanding. Even after some years of regular panic attacks, for example, I still had no word for these profound bodily and emotional episodes. I vividly recall browsing the shelves of a a bookshop and first discovering a book that gave this daily scourging phenomenon a name. The panics immediately became more knowable, less scary. Symptom names can give us ways to define intense experiences of pain or amorphous senses of unease; ways to compare what we are going through with other people; courses of action we might therefore follow. But the medical language of menopause is not a friendly or attractive one; it is a lexicon of atrophy and dysfunction, of parts shrivelling, drying, not working according to the manual, and of offputting and impersonal drug and treatment names.

What if we enacted a new language, or a reclamation – as in the refiguring of ‘queer’ and ‘crip’? Cat Chong (Chapter 11) brings our attention to the language around menopause and endometriosis. What might a new person-centred, ritual-centred language of menopause sound like? A language of tenderness and care, of respect and richness of knowing? How might such language shift our perceptions and experiences? It is worth reminding ourselves, as Lynne Franks does in discussing the wise woman (Chapter 19), that menopause as a health issue is not the only way of characterising the changes that occur as we humans age.

Menopause has come to be understood mainly as a confluence of hormonal changes, commonly categorised into three stages: perimenopause, which can last for a number of years as the hormone balance shifts, stops, starts, stutters; menopause, when periods have ended (often recognised as when there have been no periods for a year); and postmenopause, when, although hormones may have levelled out, changes continue as we age (see the Menopause Literacy section for medical as well as common usage of these terms). There is also hormonal menopause, deliberately induced by blocking oestrogen and sometimes by prescribing other hormones; and surgical menopause, where the womb and sometimes also ovaries are removed. Several chapters in this book relate different experiences of the deliberate withdrawal of female sex hormones. Cat Chong’s friend Paige (not their real name) talks about hormonally induced menopause and Lee Hurley voices the often unheard issues of female-to-male transition (Chapter 9).

As Dr Padmini Murthy discusses in her global view of menopause, human rights, and social and anthropological research (Chapter 2), women of different ethnicities and in different countries can experience symptoms in a multitude of ways. These variations can be cultural, so that where older women are more valued, or have greater freedom or power than those of childbearing age, they may experience menopause as a more positive change. However, it is worth noting that greater respect and freedom for older women in a community does not necessarily mean a valuing of older womanhood: Dr Eleanor Nwadinobi, president of the Medical Women’s International Association (MWIA), highlights, through a personal anecdote, how it can in fact be that women of this age are seen as, or more like, ‘men’ and this is where the respect comes from (Chapter 14). Patriarchal power structures have not necessarily been dissolved or challenged.

Variances in symptoms may also involve physiological and dietary factors; for example, women in Japan consume large amounts of phytoestrogens and also report fewer hot flushes and night sweats than women in North America. The lack of a specific term for menopause in Japanese is often mentioned and became noted in the West particularly through the writing of anthropologist Margaret Lock, who spent a decade researching the subject. Where there is no specific word in a language for a condition of being, we need to be careful: it could be because it is not experienced, or because it is understood within a different social context; however, it may also be because it is under-recognised or under-valued.

Income level, social position, sexual orientation, cultural background, ethnicity, primary relationships, work, support networks, self-image – all of these will feed into and form our experience of menopause, along with our ability or desire to access medical treatments for problematic symptoms. The differences in access to appropriate healthcare can be shocking: Clare Barstow, for example, exposes the ways in which women in the UK criminal justice system have been appallingly let down (Chapter 10).

We will also be affected by our relationship to fertility and motherhood. Menopause for someone with no children, or who had wanted more children, may bring very different emotions and accommodations than for someone who is a parent comfortable with the size of their family. It can carry a particularly poignant grief for those who have longed for children but been unable to conceive or carry to term. Tessa Sanderson (Chapter 21) speaks movingly and frankly about her journey through IVF, and how, after menopause, she decided to adopt. However, even where the desire for parenthood has not been so close to one’s heart, menopause itself can trigger an unexpectedly shocking recognition of this loss. It is also worth remembering that early menopause – or premature ovarian insufficiency (POI), as it is called in the medical terminology – and other gynaecological or hormonal difficulties can afflict much younger people, bringing that loss into years when there can often be an assumption that the ability to become pregnant is a given.

‘In Ireland I am hearing from more young women with POI, which supports the growing evidence that it is on the increase,’ menopause educator Catherine O’Keeffe told me. She continued:

POI occurs under the age of 40 and can happen as early as your teenage years. The ovaries stop producing eggs, generally years before they should. The ovaries also stop producing oestrogen and progesterone and so menopause commences. It is further compounded by the fact the ovaries often don’t stop fully – they can fluctuate over time. So, as in perimenopause, a period, ovulation and even pregnancy can occur, but this is at a much younger age, and for pregnancy the statistics are much lower – 5–10% of women with POI may still conceive.

As those with POI can be very young, there are long-term health concerns that need particular focus and attention, for example, heart, bone and brain health. ‘The Daisy Network in the UK is a fantastic support for POI and I run the Irish support network for this group,’ says Catherine (see page 188). ‘I often say to women, if they find natural menopause a challenge then POI and surgical induced menopause come with a harder burden. Who of us would like to be experiencing hot flushes at the age of 15? And this does not touch on the psychological impacts of POI. Much more needs to be done to educate women on POI and ensure we have the right supports in place.’

Each person will also have their own particular blend of hormones, their own individual menstrual cycle, their own perception of themselves and what it means to be a woman (or man) against which to judge whether menopause brings relief or anguish, new curse or new freedom, or not a great deal of change at all. I myself had probably always been ambivalent about gender. I did not relish the idea of being a woman, and in the years of my childhood and early secondary school, I had not needed to consider myself in that way. As an only child, learning from father as well as mother, feeling their dual support and bearing their twin ambitions, I had received the message that I could go wherever my own capabilities and hard work took me; it was as though I would be excused from sexism. In my voracious reading, I cast myself as the knight, not the princess; I would be Galahad, not Guinevere. Over the years since, I have explored, been troubled by, experimented with, come to love, forgotten about, accepted and wrangled with being a woman, and all that this has entailed in personal life, society and culture in Britain from the late 1970s to 2020. This is the context of my own menopause.

Carol Russell writes eloquently (in Chapter 4) of the rage and grief brought to the surface by her questioning of the memory talents that have been central to her identity as a storyteller, and by societal attitudes: ‘At this time in my life, society doesn’t expect me to want to achieve the dreams that have been deferred by my womanhood and my African descent, but instead it would prefer me to take a step back and allow the young to have their turn.’

Menopause is not the neat cut-off that the term itself or medical definition suggest. Not just hormones; not only an end of menstruation. It is also, as Sophia Tzeng contemplates (Chapter 5), a shift in our relationship with mortality, with ageing, with our bodies and their rhythms. We also need to question what is collected into the ‘bundle’ of what we are referring to in our day-to-day use of the word: what is down to menopause and what is about midlife? What is hormonal shift and what is life shift? What aspects of our experience are more about the ongoing progressions of ageing than a single event or condition – especially one that is often characterised as a ‘lack’: a loss of oestrogen and loss of youth and fertility?

The time of menopause can also be about a transformation of energies – of wanting change, of needing energy to move things that are stuck. A time of risks and of surprise – of being surprised by ourselves. A time of finding and developing a new voice. In my case, poetry suddenly seemed the only way to adequately express what I was feeling, and this has become a new and welcome direction in my life. For Jennifer Nadel (Chapter 1), co-founder of Compassion in Politics, menopause compelled her to speak out about the injustices in the political and social landscape around her.

It can be a time of questioning existing relationships and either revitalising them or embarking on new ones. Our closest ties can be re-forged or newly forged. Sophie Watkins and Stephen Purvis (Chapter 7) discuss with candour and warmth how their own relationship had to evolve and grow to cope with Sophie’s surgery and its aftermath, right from the beginning. We may also review our accepted ideas of our sexuality, or decide to live it more authentically. Carren Strock, for example, points out that the majority of the women she interviewed for her book Married Women Who Love Women were in their mid-thirties to mid-fifties when their same-sex feelings became apparent – when many were going through perimenopause or reaching menopause (Chapter 8).

For my generation of women in the UK, and other countries where motherhood is being put off until later (I was a month shy of my fortieth birthday when I had my son) and our elders are living longer, menopause also sits between or overlaps the caregiving roles of mother and daughter. My son was 6 when I began perimenopause at the age of 46; 11 when my periods stopped in 2015. My parents were in their eighties. For me, the meno-‘pause’ was that tiniest of gaps between nurturing a young child and taking on increasing care and life responsibilities for my own mother and father. I am most definitely part of the so-called sandwich generation. In some ways, I hardly allowed menopause symptoms any attention at the time: there was too much else going on.

It really sank in, talking with Sandra in our Menopause Café conversation (Chapter 20), that I had been hugely stressed, just not noticing it. I was lucky that my partner and son were understanding and supportive, but in a way I had ‘put off’ dealing with uncomfortable symptoms because there was no space to recognise or think about them properly; no time to stop and do anything about them. Symptoms around vaginal dryness, painful sex, and what I now realise was probably the beginnings of urinary incontinence, and vulval tissues that had become so thin they suffered small tears if I wasn’t careful when washing. It was only later, after I had confided in a sympathetic GP when everything became too much, that I felt able to take stock and look at what I myself might be needing. I know I am not alone in this pushing down of my own health needs. It is something that women have traditionally done, and something that is highlighted particularly starkly in Shad Begum’s conversations with women in her Pashtun region of Pakistan (Chapter 6).

In both my own lived experience and the experiences of the many people I’ve spoken to, it is clear that menopause cannot be defined neatly; but part of the issue we face in demystifying the menopause is wrapped up in the lack of an open and honest conversation about it across the spectrum, from policy-makers and medical practitioners to those going through it.

So why do we struggle so much with the M-word?

Talking about female bodies, and acknowledging their humanity – their pains, their discomforts, their amazing imperfections, their wonderful physicality – has been a taboo across many cultures for many hundreds and thousands of years. Female physicality remains a subject that can be difficult to discuss outside an intimate circle, whether of friends or relatives, or of those strangers we quickly connect with through the discovery of shared life events.

In women’s medicine, this taboo, and biases around research and drug testing, gender and ethnicity, and believing (or more precisely, not believing) the lived experience of women who present as patients, have led to misinformation and to women going without essential and even life-saving treatments. Gender bias in medicine, and in data collection and analysis more widely, has been laid bare in works such as Caroline Criado Perez’s Invisible Women and Gabrielle Jackson’s Pain and Prejudice. Women have been systematically omitted from clinical trials, even of treatments for women, and female animals not used in relevant experiments (although personally I welcome any omission of animals from experimentation). Jackson cites Maya Dusenbery, who wrote how ‘a National Institutes of Health-supported pilot study from Rockefeller University [in the US] that looked at how obesity affected breast and uterine cancer didn’t enrol a single woman’. During my research I interviewed Mandu Reid, leader of the Women’s Equality Party (WEP) and founder of The Cup Effect, which works to empower women and girls across the world by raising awareness about menstrual cups, and she spoke passionately about this issue:

The genesis of that problem is something really deeply structural and it is this fact of how research isn’t done on female subjects and historically hasn’t been done on female subjects to the same degree as male subjects. There is this extraordinary example of a libido drug called Addyi [flibanserin] and the safety testing on this female libido drug was carried out on twenty-three male subjects and two female subjects. Now that for me is a ‘poster girl’ or poster boy example of exactly what’s wrong with our medical system.

Reid also referred to the difference in diagnosis rates between men and women as a further example of the challenges women’s healthcare faces: ‘I was really alarmed when I learned that despite women visiting the GP significantly more frequently than men do, it will take four and a half years or longer for a woman with cancer to be diagnosed and two and a half years longer for a woman with diabetes to be diagnosed.’ There are also numerous worrying examples that come up throughout the book, and these differences are not just found between men and women, but also between women, depending on ethnicity and cultural or socioeconomic background. Dr Christine Ekechi calls for more and better research, pointing out the lack of understanding, for example, of why there is a prevalence of fibroids in Black and Asian women (Chapter 18). Dr Wen Shen, in the same chapter, reflects on the incredibly difficult experiences women have been through and continue to suffer with – when better research, education and attitudes towards women’s health could make all the difference.

As well as the paucity of medical dialogue and research, the missing conversation around menopause has personal, social and cultural consequences. When locked in our own concerns, without a communal space to share experiences and be validated in them, anxiety and fear can take hold. Finding a companion on the road of menopause, going through something of what we are going through, can bring the ‘oh thank God, it’s not just me’ moment that a number of people I have spoken to for this book have talked about. It’s not just about information, it’s about being part of a collective rather than out on our own. In her Menopause Café conversation (Chapter 20), Helen Kemp speaks of finding a ‘tribe’ among those experiencing menopause.

I have also been struck by the number of people who did not learn about menopause, or even much about menstruation, from their mothers or other older female relatives. In my family, menarche – the beginning of periods – was something my parents were open about. We even went for dinner to mark it as an achievement to celebrate (I was slightly mortified, not appreciating the attention in my mid-teens). Both my mother and father were involved in discussions around puberty and relationships: perhaps unusually in suburban 1970s England, given that they were of the generation who reached adulthood in the recently post-Second World War years, before the so-called ‘permissive society’. My mother also talked about menopause, and in particular hot flushes, in her later forties, though not other symptoms that I can recall. (Perhaps hot flushes are the most-recognised symptom of menopause because they are simultaneously prevalent and hard to hide in public.) Going back further, her own mother – my grandmother – had struggles with her mental health, which returned in her late forties and fifties and for which she experienced the harrowing treatment of the day, which included ECT (electroconvulsive therapy). Although there were other factors, I now wonder whether part of her psychological distress may have been prompted by the hormonal turbulence of menopause? How many women, over the decades and centuries, might have been misdiagnosed in this way? How many given inappropriate and even damaging treatments that made matters worse, not better? We come back here to the drastic surgical ‘treatments’ of the nineteenth century – and the fact that women today can still be dismissed as ‘hysterical’ when they describe pains and symptoms that a doctor does not readily understand.

For some, the intergenerational silence results from specific cultural and religious traditions and taboos, which are touched upon in chapters throughout the book, and perhaps highlighted most powerfully in the voices of women from Pakistan and Afghanistan. In more secular Western societies, the silence can also be related to the construction of shamefulness and diminishment associated with being a woman, and in particular becoming older as a woman – as Caryn Franklin analyses (Chapter 15). But there is a more widespread disconnect, too, which applies to other areas of what used to be traditionally passed-down knowledge. These days, we turn to YouTube for cookery tips and websites for health advice. We have gained computer memory but lost familial memory – a generalisation, as I know from the fact my own pastry-making skills were passed on to me by my mother, but worth noting in relation to women’s health and knowing what and who to trust when it comes to caring for our reproductive and bodily selves. Faye Clarke, one of the Australian nurses who has contributed her experience (Chapter 17), also points out the disconnect brought by colonisation for First Nations people there: ‘The impact of colonisation has been difficult in that generational conversations have been interfered with and the knowledge of times past has been interrupted. This has a big impact on future generations of women.’

It feels important to reconnect, so that education is not only what we read in leaflets, but what we share face to face, generation to generation – even if, in the socially distanced times in which I am writing this introduction, in the midst of the spring 2020 coronavirus lockdown, that ‘face to face’ has to be digitally enabled.

If we don’t engage with others, we can become sealed in the bubbles of our own particular demographics, either believing on the one hand that every-one else’s experience will be similar to our own, or that other people’s lives are ‘different’ in some essential way. This can lead to damaging assumptions and the perpetuation of prejudices and bias, which need to be actively recognised and countered. In her film-making and advocacy, Afghan-born Arzu Qaderi, for example, challenges the media stereotypes of women in her home country to provide a more nuanced understanding, by talking to Afghan women and sharing their real stories (Chapter 16). Throughout the book, we have conversations and perspectives from the UK and US, from Pakistan, Australia, Italy, Nigeria, Afghanistan, Ireland, Canada, Singapore, which are by turns heartfelt, eye-opening, lyrical, shocking, galvanising and speak to the profound impact menopause can have on all areas of life from the personal to the political, from the social to the economic.

Indeed, it is estimated that 14 million working days a year are lost to the UK economy due to women being unable to work because of menopause. But if we go beyond nation and economy, to look at people’s actual lives, what do those figures mean in terms of lost household income, job anxiety, halted career progression, workplace bullying, the gender pay gap? To what extent does menopause – like pregnancy and motherhood – shape and limit the choices people make in their work, and affect how they are perceived in that work? Beyond the stereotypical (and also true) image of the menopausal woman having a hot flush in the boardroom, this is something that has a deep effect on those in all kinds of employment, and unemployment. Recognition of the impact of menopause in the workplace, and steps to address this, are thankfully beginning to be taken seriously, certainly in European countries and the US. Catherine O’Keeffe reports on the new initiatives around women’s health in the Republic of Ireland, for example (Chapter 13).

A re-education through listening and talking

Learning and understanding is a collaborative process: it is about a making of knowledge with others; it is a relationship. This relationship may be with people we speak to in person, or with what others are writing in our own time; with collective understandings passed down orally, or with the writings of individuals stretching back through the centuries. It is also a knowledge ‘written in the body’: in our relationship to our selves. Certainly, this is how I have come to view my own knowledge and understanding about menopause.

In the making of this book, I have spoken to and heard from many people, nudging my understanding forward with each encounter. The book itself has also been developed in relationship with my commissioning editor at Flint, Jo de Vries, with whom I have talked through ideas and directions, all along the way. We have each of us been changed by the process. As Jo wrote to me, in the final stages of putting together the manuscript:

One of the most profound things for me has been how much it’s made me think about how I’ve passively accepted so many things about my own menstrual and gynaecological health as being a ‘woman’s lot’. I now realise how often I’ve ignored or felt ashamed of so much of that part of being a woman; how little I’ve educated myself about things that could have been addressed or I could have got help with. Working on this book has really changed my perspective on that and I hope will mean that I can enter the menopause feeling more empowered to ask the right questions and find out information rather than being fobbed off or being too ‘frightened’ or ashamed to complain.

The need for education and empowerment is a theme that runs through the contributions to this book. As I gathered information myself, I decided I wanted to know more about HRT, since hormone therapies (‘replacing’ oestrogen and sometimes progesterone) are often the main treatment route offered by GPs and other health professionals. As Dr Shen points out, however, a number of potential symptoms listed for menopause (see page 293) are due to more complex interactions, including lifestyle factors and the ageing process. I also wanted to know why HRT remains far less prescribed, certainly in the UK, in the early twenty-first century than in the 1990s. I had known that I did not want to take so-called systemic HRT (for the whole system, in tablet, gel, patch, or implant form), but I did research and opt for oestrogen pessaries to alleviate the vaginal dryness and skin thinning. I talked to Dr Caroline Marfleet, a consultant in reproductive and sexual health who has specialised in women’s health for more than forty years, to discuss this further. Issues around HRT, which was first introduced in 1965, arose with the publication in 2002 of initial findings from the Women’s Health Initiative, a clinical trial in the US, and results from the Million Women Study in the UK that came out in 2003. These studies taken together suggested links between types of HRT and increased risk of coronary events, stroke, thrombosis and cancers, in particular breast cancer, although later analysis has questioned some of the risk levels given in initial published findings.

The NHS, said Dr Marfleet, does not have a specific policy to avoid prescribing HRT, but ‘some [GP] practices decided against HRT and took a “no risk” approach rather than finding out more’. In part, this was a financial as well as a health decision: they did not want to be called to account in our current ‘blame society’. Dr Marfleet pointed out that recent studies show HRT can have preventative and protective aspects for quality of life and moods, osteoporosis, vulvovaginal and urinary issues, and heart disease (if started within ten years of menopause). ‘Not all HRT is the same; the types of oestrogens and progestogens used in HRT are now known to have different effects and outcomes on the female system,’ she explained. ‘There are also different effects depending on the method of delivery as evidence has shown a small increased risk of blood clots with oral HRT, which is generally not seen with transdermal HRT (gels and patches) as these do not pass through the liver.’

HRT is one, hotly debated, way in which menopause has become medicalised in the modern age, and in the past few years there have been more radical developments that may change our definition of it altogether. While the Medical Women’s International Association (MWIA) and other organisations define menopause as a natural part of ageing, scientists in Greece have apparently been able to ‘reverse’ it by ‘rejuvenating’ the ovaries of menopausal women using a blood plasma treatment. At the same time, many women are continuing with long-term HRT. So, one question is whether we now live in postmenopausal, or even non-menopausal times? Some people advocate an acceptance of menopause as an important stage of life: one that should be ritualised and recognised, and that can bring spiritual maturity and wisdom. For others, HRT has been a lifeline through changes that have undermined their physical and mental health, and relationships. Any questioning of the medicalisation of menopause (and the profits of the pharmaceuticals industry, for example) needs at the same time to prioritise and think through what is important for women’s health and well-being.

What of the future? Initiatives that put this reclaiming of women’s health at the foreground are beginning to spring up. Dr Shen has set up a new Women’s Wellness and Healthy Aging Program at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, bringing together specialists from the many different areas of health that can be impacted. Mandu Reid, as leader of the Women’s Equality Party (WEP), is excitingly proposing a Women’s Health Institute in London:

What we’re fighting for in London is an acknowledgement of all the ways in which women are disbelieved, misdiagnosed and let down by the health system. And it’s the whole cycle – it starts at research, it moves on to diagnosis and it moves on to treatment. In a way women are second-class citizens when it comes to health outcomes that they’re on the receiving end of.

We spoke about the need, identified by many contributors to this book, for better training for primary care doctors. ‘When GPs are being trained, as part of their core training there need to be modules that are compulsory for them to undertake that are designed and informed not only by those who have medical qualifications but also women who have been through menopause and, crucially, have had to navigate the health system blind spots around how menopause is treated,’ said Reid.

She and the WEP are keen to ensure there is a focus not only on the inequalities for women, but between women. Asked about the differences in health outcomes for BAME women and women in low-income groups, Reid spoke, like Dr Ekechi, about the importance of research. This needs to be high-quality research that will:

Examine and drill down to understand what the source or sources of these inequalities are. We know that in this country Black women are five times more likely to die in childbirth than their white counterparts and I find it devastating to know that that’s the case, although I am pleased that someone has studied that. But what’s missing are further lines of enquiry and proper research to understand why … More money needs to be invested in women’s health research full stop, but a portion of that cash needs to be ring-fenced as a deliberate, purposeful thing to examine the differences between groups.

This will mean convincing senior medical and clinical practitioners. ‘Unfortunately, money talks,’ admits Reid. ‘But if you look at healthy quality of life, women’s healthy quality of life is shorter than men’s, even though women live longer in total. Now, if women have a better healthy quality of life that would be better for our families, for our communities and for the economy. So, if somebody needs a business case for this research, then this is it.’

Reid’s mother is originally from Malawi, and she herself, with The Cup Effect, works with girls and women in lower-income countries. One of the things that Reid has been passionate about with The Cup Effect is engendering better ‘menstrual literacy’. She reflects that:

Actually a 13-year-old girl in Sheffield has a lot more in common with a girl growing up in a rural part of Malawi, when it comes to her attitudes and experiences of menstruation, than I would have thought. So, the shame, the stigma, the embarrassment is really shared by the people in both of those communities. The big difference is really the ready access to menstrual products.

And she feels that this also applies to the menopause:

I think this whole thing of informed choice applies as much to menopause as it does to menstruation. We need menopause literacy too … It was certainly absent from my education. I’m 39 now and I’m training myself to be vigilant as I know I could be heading for the perimenopausal part of my life, but I didn’t even learn the word perimenopause until 2 years ago. Why didn’t I learn that when I was a youngster? … It’s really important whether you’re talking about puberty or the later periods of your life where your body is changing, so your life is changing.

On the one hand, menopause may be seen as a universalising experience – something all those with female anatomy or hormone cycles will go through, in one form or another – but that doesn’t mean putting forward a model of menopause that privileges particular experiences and understandings. From the outset, the aim of this collection has been to bring together voices from different walks of life and cultural backgrounds, to begin unravelling and listening to the complex, difficult, worrying, poignant, creative variety of lived experiences.

As with the menstrual movement before it, the debate and the mood around menopause are changing. In the past few years, there has been a shift – something that Rachel Weiss reflects on (Chapter 20), when talking about setting up the groundbreaking and now international Menopause Café movement. There is a growing body of people and websites providing support, campaigning, making menopause matter to the wider population – people like Diane Danzebrink, founder of the #MakeMenopauseMatter campaign in the UK (Chapter 3), Catherine O’Keeffe, who extended this campaign to Ireland, and Aisling Grimley, who set up the My Second Spring website from her home in the Republic of Ireland (Chapter 13).

The aim of this book is to open up the exchange of conversations about menopause, so that they can take place not only in local gatherings, whether in person or online, but internationally, by reaching out to people across the globe. It is not a ‘how to’ manual or advice book – although you may find the stories of those here strike a chord in mapping your own menopause and deciding what might be helpful or necessary for you. It is based on an understanding of menopause as unique for every person; there are commonalities that reach across continents, and at the same time stark differences within families – between mother and daughter, sister and sister. This book is also based on a belief that all of us, whatever our gender or assigned sex, could benefit from understanding more about that variety of experience. Menopause as not just a ‘women’s problem’, but something social, cultural, familial and a fact of life that affects almost everyone in some way: as sister, brother, friend, partner, child, or as someone going through it.

This book is only a beginning, however, and there is only so much it has been able to cover in these pages: there need to be more and wider conversations; more women, men and non-binary people of different backgrounds and experiences brought to the table, having their contributions valued and listened to. There needs to be a range of culturally appropriate safe spaces in which we feel able express and share, and discover what will be helpful in our own particular context. We also need places and networks to debate and grow what can and should be done on a broader societal and global level.

In exploring the physical and very human geography of menopause, putting this book together, talking to and virtually ‘meeting’ with people around the globe, I have learned so much, both about other people’s experiences of menopause, health and ill health, their lives and hopes, and also about my own understanding of menopause. I hope that, as readers, it touches and empowers you too.

This book is dedicated to my mother, June Marjorie Harris (June 1931–April 2019), and to her mother, and her mother, and her mother … and to all of our future generations.

Caroline Harris

May 2020

Caroline Harris is an author, educator, publisher and poet. With more than twenty-five years’ experience in journalism and publishing, she began her career at feminist magazine Spare Rib and spent seven years with The Observer. More recently, she co-founded book creation business Harris + Wilson and has lectured in publishing, including as Course Leader for the BA Publishing at Bath Spa University. She is the author of Ms Harris’s Book of Green Household Management (John Murray) and young adult novel Consequences: Holding the Front Page (Hodder Children’s). Her debut poetry pamphlet, SCRUB Management Handbook No.1 Mere, is published by Singing Apple Press. She currently lives in Bath with her partner and son, and is studying for a PhD in poetic practice at Royal Holloway, University of London. Her interests range from yoga to deer, cycling to ecological philosophy, women’s lives to the life of words.

1

It’s Time to Make ‘Normal’ Visible

Compassion in Politics founder and bestselling author of WE: A Manifesto for Women Everywhere, Jennifer Nadel explores how the menopause turned her life upside down and set her out on a new path.

I’ve just finished writing my first novel. It’s the spring of 2010 and I’ve been invited to read from it at a conference hosted by one of my writing heroes – an attractive, distinguished and celebrated male novelist. The conference’s theme is sex. So, I begin to read the scene where my 15-year-old female narrator loses her virginity. I’m comfortable with the material. I’m confident reading in public. But within seconds of standing up, I feel myself flush deep red and beads of sweat begin to form on my forehead. By the end of the reading I have sweat running down my face. I must look as if I’ve just finished running a marathon. Those around me – including my literary heart throb – comfort me, assuming it has been a traumatic ordeal to read so explicitly about sex in public. They were wrong. It was, I now know, my first hot flush.

I was unprepared. Like the girl in the shower at the start of Carrie, who becomes hysterical when she discovers she is bleeding because she doesn’t know about periods, I knew nothing about this biological and inevitable process. A process whereby my periods would dry up and I would begin an intense and largely uncontrollable biological, intellectual and spiritual journey.

In my forties, the menopause wasn’t something any of my normally liberal friends had discussed. My initial shock and embarrassment soon gave way to fascination. I was intrigued that my body could suddenly and unexpectedly generate so much heat. I had a new superpower. I could go from cold to boiling in no time at all. My body had become an out-of-control radiator that would suddenly perform its turbo-charged stunt without warning. At night, I’d wake to find my sheets sodden. Pools of sweat would collect on my chest between my breasts. My hair would be drenched.

But the hot flushes were the least of it.

To accompany them came all manner of hormonal shifts, not dissimilar to a second puberty. Mood swings. Uncontrollable rage. A loss of control. I found myself furious over the smallest thing, sometimes aware that I was overreacting, sometimes not, but never able to stop myself once I’d started. I couldn’t explain how my personality had changed so dramatically. For my first forty-eight years on this planet I’d been dismissive about all things domestic. And now, here I was raging about the cutlery. My children started to walk on eggshells, and I began to wonder if I’d had an unrecognised head injury or perhaps a brain tumour. At the same time, I noticed a diminishing of maternal feelings: a hardening in the heart area. For the first time, I became able to loosen my vampiric grip on my offspring. I went from smother-mother to laissez-faire in lightning speed: ‘They’ll work it out’ replaced ‘How am I going to make this better for them?’

At the same time came a desire to be free – to upend my life and finally give it a full and true expression. I was well aware of the privileges in my life, as a middle-class, cis, professionally educated white woman, but I was overcome by a deep dissatisfaction with the state of things in the world and haunted by a feeling that whatever I had done was not enough. I felt that I was surrounded by phoneys – a throwback to my adolescent rage against the hypocrisy of all things. I felt an urgent need to remedy the situation, accompanied by a gnawing dread that change was now impossible: it was too late.

There was also a crippling anxiety, out of all proportion to the task at hand. I found myself at an airport one day about to leave for a holiday with close girlfriends but unable to get on the plane, sobbing and seized by an unexplainable terror. A haziness took hold of my brain. I used to think I was reasonably intelligent, but now I lost the car on a regular basis and forgot close friends’ names. I could no longer be sure that if I started to express an opinion my brain would be able to marshal the facts I knew were there to back it up. My kids booked me in for dementia testing; luckily I didn’t qualify but it was close.

I had been privileged with a good education, but still I knew nothing. It took me the first few years to piece together the many disparate ways in which the menopause was affecting me.

Physically there were more seemingly unrelated symptoms. Like the thinning of my hair, which would fall out by the handful. I thought I was going bald and not just on my head – eyebrows, lashes and elsewhere as well. Sunburn down the parting became a thing and, like a middle-aged man, I had to start wearing hats in the sun. Simultaneously, hairs grew unbidden in all sorts of random and unwelcome places. Those occasional mole hairs doubled in size. They could now appear unpredictably almost anywhere, obliging me to make a coma-pact with my best friend – a reciprocal agreement to tweeze out the worst offenders if either of us should end up paralysed. The snowy down of an early adolescent boy appeared on my cheek and chin. Nostril hair, it turned out, was not just for hirsute men. My skin lost its elasticity; my stomach became distended, my boobs emptied. My periods stopped and then returned heavier than ever. A last desperate throw of the dice by a cycle that knew it was on the way out. Stress incontinence was now not just for trampolines but for any energetic activity when my bladder hadn’t been fully emptied. Scaly, old-person skin emerged on my legs. Everything began to dry out.

Then, when the penny finally dropped, came the panic over HRT. Would it cause cancer? Would it give me a stroke?

I resisted the very idea of it to start with. This was a natural process, I argued; surely I should feel and learn whatever lesson was buried in it? But, like childbirth, not all of us can rely on our breath. Some of us need medical intervention and extra help. As the symptoms ramped up and my unexplained mood swings took their toll on an already wobbling marriage, I succumbed to the idea that I might not be able to manage this myself.

By this point, those friends who could afford to were spending small fortunes on alternative therapies. I myself visited a string of passionately recommended ‘experts’ who prescribed a cocktail of creams that would be mixed specially for me in another country. One such ‘expert’ suggests that rubbing these creams into my labia will bring me heightened sexual pleasure in a way that makes me feel this is more about his sexual gratification than mine.