12,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

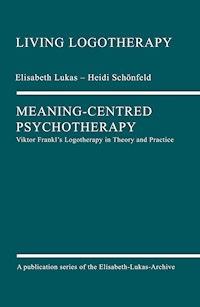

- Herausgeber: tredition

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Living Logotherapy

- Sprache: Englisch

Viktor E. Frankl, the founder of the "meaning centred psychotherapy" called logotherapy, was awarded 29 honorary doctorates from around the world for his work. One distinguishing feature of this form of psychotherapy is that it works well in the long term as well as providing short time relief. This is more and more important in view of the increasing numbers of people in the world who suffer from mental instabilities or disorders. The two renowned authors of this book offer exciting insights into the practical application of logotherapy. In doing so, they inspire readers to come up with ideas and tips for their own lives.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 312

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Living Logotherapy

Published by

www.elisabeth-lukas-archiv.de

© 2019 Elisabeth-Lukas-Archiv gGmbH

Dr. Heidi Schönfeld

Nürnberger Straße 103 a

D-96050 Bamberg

This English edition published with the kind permission of Profil Verlag. Originally published in German as Sinnzentrierte Psychotherapie. Die Logotherapie von Viktor E. Frankl in Theorie und Praxis. © 2016 Profil Verlag GmbH München Wien

Elisabeth Lukas, Heidi Schönfeld

Meaning-Centred Psychotherapy

Viktor Frankl’s Logotherapy in Theory and Practice 2019

Translated from the German by:

Dr. David Nolland, Oxford

Cover design, typesetting and layout:

© Bernhard Keller, Köln

distribution: tredition, Hamburg

ISBN 978-3-00-064274-6

Elisabeth Lukas – Heidi Schönfeld

MEANING-CENTRED PSYCHOTHERAPY

Elisabeth Lukas – Heidi Schönfeld

Meaning-Centred Psychotherapy

Viktor Frankl’s Logotherapy in Theory and Practice

LIVING LOGOTHERAPY

A publication series of the Elisabeth-Lukas-Archive

Foreword for the series "Living Logotherapy"

"In our time, people usually have enough to live on. What they often lack, however, is something to live for." This is how Viktor E. Frankl, the Viennese psychiatrist and founder of logotherapy, summarised a problem that is just as relevant today as ever. Elisabeth Lukas, a clinical psychologist and psychotherapist, has an international reputation as Frankl's most important student. In her many books, she illustrates how logotherapy provides help in cases of mental illness, enriches the everyday life of healthy people and inspires us all to lead a meaningful, fulfilling life. Her books illustrate how humane, authentic and up-to-date a "living logotherapy" can be. The main objective of this new series is to make her books, which have enjoyed lasting success in the German-speaking world, more accessible to speakers of English.

Many people have worked hard to make it possible for the Elisabeth Lukas Archive to publish this new series. Particular thanks are due to our translator Dr. David Nolland, who has produced a fluid text that remains very close to the original. He has excellent knowledge in the field of logotherapy and supervises this series in all matters relating to the English-speaking market. Thanks are also due to Prof. Dr. Alexander Batthyány, who supported us from the beginning and will accompany this series as a guide. The formatting and layout is due to Bernhard Keller, and the beautiful presentation of the books is wholly attributable to his expertise.

The first book in this series is a collaborative project. It combines discussions of the theory of logotherapy by Lukas with numerous case studies by Schönfeld. Thanks to Dr. Kagelmann of Profil Verlag, the holder of the rights for the German version of the book, for generously giving his permission for an English language version.

All that remains is to wish this book success in the Englishspeaking world. May it give readers a glimpse into the vitality and relevance of logotherapy!

Dr. Heidi Schönfeld

Director of the Elisabeth-Lukas-Archive

Translator’s Note

Logotherapy presents a particular challenge for the translator. Viktor Frankl’s own works are full of humour and metaphor, and his distinctive way of making his point often relies heavily on wordplay, poetic forms of expression and nuances of language that combine colloquial language with philosophically suggestive formulations distilled from a profound understanding of the history of European thought. He coined a number of original terms and concepts that play a key role in his work. Frankl was often dissatisfied with the published translations of many of these key terms, and his own translations, where available, provide valuable clues to his thinking.

Elisabeth Lukas has a distinctive written style that shares the aforementioned features of Frankl’s writing. She has continued in Frankl’s footsteps linguistically as much as she has intellectually and spiritually. Frankl never saw the logotherapy he had originated as something finished and set in stone, but as a system of thought that should continually be developed in response to the inexhaustible insights into human nature arising from his focus on meaning and the possibilities of the human spirit.

I have done my best to capture the personality and nuance of Elisabeth Lukas’ and Heidi Schönfeld’s writing by staying very close to the original text, and I have benefited from extensive help and advice from the authors and other experts in logotherapy in the case of various technical points which have proved difficult. We are satisfied that the result is a text that remains faithful to the legacy of Viktor Frankl and Elisabeth Lukas, and provides a valuable reference of "living logotherapy" for the English-speaking world.

Dr. David Nolland

Contents

Foreword for the series "Living Logotherapy"

Translator’s Note

PROLOGUE Elisabeth Lukas

THE ANTHROPOLOGICAL FOUNDATIONS OF LOGOTHERAPY Elisabeth Lukas

CASE STUDIES IN APPLIED LOGOTHERAPY

I've not slept for years Heidi Schönfeld

Topic: on sleep disturbances Elisabeth Lukas

Mrs B and her "schlurfed"-away anxiety Heidi Schönfeld

Topic: panic attacks Elisabeth Lukas

Compulsion, let go! Heidi Schönfeld

Topic: intrusive thoughts Elisabeth Lukas

Chinese jump rope in God’s hands Heidi Schönfeld

Topic: paranoid psychosis Elisabeth Lukas

Couples’ therapy with "half a couple" Heidi Schönfeld

Topic: marital problems Elisabeth Lukas

An ambivalent separation Heidi Schönfeld

Topic: alcoholism Elisabeth Lukas

Florian, Fritz and "Jürgen" Heidi Schönfeld

Topic: bereavement counselling Elisabeth Lukas

EPILOGUE Elisabeth Lukas and Heidi Schönfeld

The Authors

PROLOGUE

Elisabeth Lukas

Viktor E. Frankl, who lived from 1905 to 1997, is one of "Austria’s great sons". His name is extremely well-known internationally – and not only amongst specialists. Countless people all over the world know of Frankl from his bestselling book Man ’s Search for Meaning (… trotzdem Ja zum Leben sagen), which has been translated into many languages and sold millions of copies. The book describes his captivity in German concentration camps during World War II as seen through the eyes of a psychiatrist and philosopher. It is an immensely powerful book because it bears witness to the inalienable dignity of human beings even under inhuman conditions and shows how it is possible to preserve an intact soul in times of disintegration. As can be seen from the flood of positive reactions, a significant percentage of the countless readers have derived courage from the book to keep going in their own challenging circumstances. Every kind of misery and suffering traps a person in some way – one is hemmed in, hopes and plans are destroyed, and one’s existence is threatened. The cause does not need to be the effect of external violence, for example from a cruel political regime, but may instead result from illness, family disaster, excessive deprivation, selfinflicted tragedy or hard-to-overcome loss, which create apparently hopeless situations of despair or resignation. Frankl’s book throws significant light on such situations; it does not gloss over or distort anything. It remains factual in tone, but its message is deeply moving: life has meaning until one’s last breath. Life offers possibilities for meaning until one’s last breath. Meaning is attainable even in the face of suffering, adversity and death. This is no illusionary assertion given literary expression by an incorrigible optimist, but a document full of genuine testimonies realistically reported on the basis of personal experience. This is exactly what gives this work from the immediate postwar period such overwhelming influence and vibrancy. Frankl’s own struggle with the challenges of incipient despair and resignation meets people in the places where they experience the same things, and gently leads them to the conviction that, in principle, they also have the strength and capability needed to survive – even in a manner that proves rewarding. And this survival is not only for themselves. What has meaning spreads out, flows towards others, unites itself via mysterious channels with the logos, which was in the beginning and never ceases to be. Frankl’s book is a hymn to the fundamental spiritual values of humanity that have emerged over millennia of cultural history.

Nonetheless, it would be a shame if Viktor E. Frankl were known and remembered by his large readership primarily for his heroic survival of concentration camp experiences. This would not do justice to his overall achievement. Frankl was a scientist at heart, and he would have developed his groundbreaking ideas just the same under different political circumstances – perhaps even more quickly than he was able to in his own time. It is for good reason that he is these days referred to in dictionaries of psychology as the founder of the Third Viennese School of Psychotherapy. He developed a comprehensive therapeutic method that decisively complemented, corrected and humanised the new discipline of psychotherapy, which was only in gestation as an independent discipline at the beginning of the 20th century. The concepts that he introduced continue to be effective in the same way at the beginning of the 21st century, even though social, economic and technological structures have radically changed worldwide – and with them the perspectives, mindsets and problems of modern society. There is something so generally valid about the picture of humanity advocated by Frankl, something so deeply resonant with the soul about the healing methods designed by him, that they are not anchored in fashions and traditions, and therefore cannot fall out of fashion.

Some of the medical terms used by Frankl, however, may now appear a bit outdated, for example the old idea of "neurosis", which was still common in the years during which he was practicing, and which he made use of in his seminal work On the Theory and Therapy of Neuroses. But what does it matter whether one speaks of "anxiety neuroses", or (as one does today) of "anxiety disorders"? Are those affected happier to have a "disorder" than a "neurosis"? Their problems are the same, no matter how they are classified, and they are what have to be remedied! What Frankl’s book has to say about how to achieve this is brilliantly thought through and meticulously explained; it continues to be valid today.

The present book has set itself the task of bringing into the foreground the merit won by Frankl as a brilliant doctor of the soul. His meaning-centered psychotherapy – logotherapy – is unique amongst the many treatment methods and approaches of varying seriousness that are on offer in today’s psychotherapy market. It stands out for many reasons.

For one, logotherapy rests on an anthropological foundation which has been worked out in detail. Every psychotherapist knows how important that is. All methods, strategies and psychotherapeutic techniques are limited in scope and fail for certain patients who are simply not responsive to them. Human responses are not predictable like those of machines. What should one do when nothing works? It is a blessing when there is a foundation that one can fall back on in such cases. A foundation is incomparably more than the sum of all individual therapeutic methods. It is a way of seeing the world and beyond the world, of seeing what it means to be human and to be oneself; it is the last and most real thing that one can believe in and hold on to. An exchange of views about this reaches even patients who otherwise refuse all offers of help. Frankl was completely convinced that the effectiveness of therapy was only to a small extent dependent on the strategies used. He thought that it was much more to do with successful "optical adjustments" – and most evaluations have proved him right. Ever since Plato’s allegory of the cave, it has been known that people make "pictures" of reality, of their own and others’ essence and existence, which, of course, can never be perfectly grasped or understood. Metaphorically, the "image quality" and even the "colour quality" of such pictures are decisive for the quality of life of the "picture maker". It is not possible to live well with distorted or excessively dark perceptions of reality. For those who constantly doubt their own value, see their environment as full of rivals or enemies, give themselves over to an absurd destiny, or torment themselves with images of a punishing God, it is difficult to experience spiritual regeneration. To want to affirm one’s life only insofar as it promises pleasure and enjoyment will soon lead to a permanent state of frustration. A false philosophy, however, cannot be overcome by purely psychological means. What is required is precisely the anthropological foundation that Frankl delineated.

For another, logotherapy also stands out because it can be used for both long-term support and short-term therapy. It has come to be recognised that long-term therapy should be avoided if at all possible. It is expensive and tends to make people dependent rather than responsible and self-reliant. There are, however, disorders that make longer-term specialist monitoring desirable (in addition to any necessary medication), because these illnesses are accompanied by emotional and cognitive breakdowns which require continual alleviation. Logotherapy is ideally equipped for this task. It also, however, proves itself to be just as well-adapted to short-term therapy in common cases of conflict and dramatisation that were previously referred to as "neurotic". Furthermore, it is ideal for use as an intervention in times of crisis or emergency, whenever a real cause for suffering has fallen upon a person and the burden seems too heavy to be able to be borne.

It is indeed rare to find such a sophisticated psycho-therapeutic concept that is so firmly rooted in its theoretical foundations and at the same time so flexible in its practical applicability as logotherapy. Frankl’s theory has been used in South American drug rehabilitation centres, in North American prison counselling, in South African peace initiatives, in Japanese clinics for psychosomatic medicine and trauma therapy, in Israeli gerontology projects, in ethics classes in European schools, in consultancy for the business leaders of international corporations – the list could be continued for many pages. The healing effect of logotherapy transcends the bounds of psychotherapy and has been enthusiastically seized upon by practitioners of psychology, philosophy, pedagogy, social work, medicine, youth work, nursing, care of the elderly, family assistance, and business management, being adapted in each case to the specific challenges involved. It cuts so close to the heart of the human species in all its complexity that it is compatible with the findings of prominent university researchers and scholars as well as with the common sense of ordinary people, with the essence of the great world religions as well as with homely wisdom, handed down over the centuries, about the question of how to live a happy life.

The present book is the result of a collaboration between one of my best students and myself. With our combined forces we would like to shine a spotlight on both the theoretical and the practical sides of Frankl’s teachings about mental health. I have taken on the difficult task of making transparent the challenging foundations of Frankl’s body of teaching, from which logotherapists all over the work derive their therapeutic successes – in this concrete case, the therapeutic successes of my co-author. She is blessed – in addition to having profound knowledge of Frankl’s teachings – with the right intuitions about how to deal with people seeking advice. She also has a mastery of what Frankl called "the art of improvisation and individualisation", which is absolutely essential in the face of individual beings and unique encounters, and she benefits from a great wealth of personal experience (see Epilogue) with which she unfailingly and with persuasive power wins back unhappy and despairing people to a life filled with meaning. She has selected seven case studies from her extensive repertoire, which in contrast to the case histories in Frankl’s books and my own, are discussed and explained in detail. This grants interested readers hitherto unsurpassed insights into the "logotherapy workshop" and the gradually flourishing healing processes within it that eventually allow patients to grow beyond their psychic weaknesses and take full spiritual control over the way they lead their lives. It has given me great pleasure to participate in this joint project, and I sincerely hope that this pleasure will be shared by you, the reader.

THE ANTHROPOLOGICALFOUNDATIONS OFLOGOTHERAPY

Elisabeth Lukas

The word logotherapy derives from the Greek word logos and signifies meaning in the context of Frankl's theory. Logotherapy is a meaning centred psychotherapy that acknowledges the fundamental role of the human spirit (Greek nous). The human spirit is rooted in the unconscious, which is why a clear distinction will be made between unconscious instinct, which is psychophysical, and the unconscious spirit. The human spirit, however, is not merely reason and intellect, which are further aspects of the psychophysical dimensions. What is in fact meant is the specifically human dimension of the multidimensional entity that we call the human being.

A specifically human dimension

The term existence is often used in philosophy for the special nature of being human. Frankl characterised as existential every process for which nothing comparable can be found in the animal kingdom. Thus, for example, the explication – in other words the unfolding of the human person – is an existential process as it goes beyond pure psychophysical development and entails unique choices and decisions. Frankl justified his focus on human spirituality with a dual argument. First, a psychotherapy which neglects the existential nature of the human being fails to make use of one of the most important weapons in the battle for the psychic recovery of a patient. Second, there is a danger of corrupting a patient with a "spiritless" view of human nature, of corroborating the patient's nihilistic thoughts and deepening the (neurotic) disorder.

In fact all forms of psychotherapy are based on anthropological premises, whether or not these are explicitly stated. In logotherapy they are openly set forth and meticulously worked out. Logotherapy attributes to human beings an ability to transcend – a "lifting power" – by means of which they can lift themselves out of psychophysical enslavement into the heights of spiritual freedom. Thus they cross over from simply being to having the ability to be otherwise. So, for example, a patient can to a significant extent either give into gloomy moods or defy them, can allow inner fits of anger to run their course or control them, can laugh off excessive anxieties or take them seriously, and so on. This invites us to make use of the resistive power of the human spirit for therapeutic purposes as a weapon in the battle for psychic recovery. Indeed, if this power is not mobilised, the focus becomes the psychophysical enslavement and dependence of the patient and the root cause therein of that gloomy mood, inner rage or excessive anxiety. In this case the affected person admittedly still possesses the existential lifting power granted by human existence, but without being conscious of it, and thus hardly daring to make use of it. Thus the erroneous assumption is strengthened that the individual is at the mercy of his or her physical and psychic nature. This is what Frankl meant by the danger of a corrupting view of human nature. Instead, the patient should be inspired and encouraged in the direction of being able to transcend the psychophysical realm.

Of course this lifting power – which Frankl also called the defiant power of the human spirit – is not able to remove all pathological determinants. The spiritual resistance of a fragile and limited being is itself fragile and limited. But spiritual freedom also includes the ability to achieve reconciliation with psychophysical limitations when and where they cannot be counteracted; for example, in the case of severe psychotic or neurophysiological disorders. As meaningful as it is to defy unnecessary states of suffering, it is equally meaningful to encounter the necessities of fate, that is, unavoidable states of suffering, with heroic acceptance. Moreover acceptance or nonacceptance is in itself a decision-making process that emerges from the human spirit and represents the final reservoir of the existential being.

Normally, it is not necessary to grapple with something difficult or to reconcile oneself with unpleasantness on a continuous basis. In a fulfilled life with a healthy balance between creative activities, satisfying experiences and sufficient periods of relaxation, physis, psyche and spirit are united together in a harmonious whole. But while the connection between the physis and the psyche is rather rigid and entrenched, the human spirit has surprising agility. The human spirit cannot be tied down: not in time, not in space–and not in body. The spiritual is movement–in one's being. Thus "being human" always shows itself most clearly when it is in motion, for example when a person is able to create distance from a part of his or her self, or transcend current boundaries. In this context, Frankl spoke of the uniquely human abilities of self-distancing and selftranscendence.

Multidimensional ontology

The logotherapeutic healing approach can only be understood in the context of Frankl’s dimensional ontology, which addresses the ontological multiplicity of the physical, psychic and noetic (=spiritual) dimensions of the anthropological unit "man" as in a coordinate system. The three coordinates (corresponding to length, breadth and height) completely interpenetrate one another without being identical. Unlike a coordinate system, however, one of the three dimensions – the noetic – is more than just one of three, as it is the one responsible for making human beings actually human: it is the essentially human dimension. In contrast to the other two dimensions it is constitutive of human existence. Biologists and zoologists are always insisting that there are species of animals, particularly apes, which are capable of extremely complex acts of thought and communication. No logotherapist denies this fact. There are only gradual distinctions between the cognitions and emotions (psychic dimension) of animals and those of humans. But it is impossible to find something "uniquely human" (as Frankl as defined the noetic dimension) amongst animals – indeed it cannot be there, because then it would not be specifically human. If anyone denies the fundamental difference between humans and animals, namely the existence of the human spirit, it is the same as denying "being human" as a distinct quality and equating it with a higher evolved "being animal".

Frankl vehemently resisted projecting the human into the animal – in other words, interpreting statements about the human spirit at a psychophysical level (even broadly defined) – which is the traditional psychoanalytic approach. Interpretations along the lines of an artistic design only having been created to compensate for a deeply seated feeling of inferiority in the artist, were deeply rejected by Frankl. When the noetic dimension is included, artistic inspiration is more than a struggle for social recognition, true human love is more than a sublimation of the sexual drive, genuine love of knowledge is more than an attempt to gain power over others, and religiosity is more than an expression of the human fear of death. Not every grief over a loss of values is a psychic depression. Not all dissatisfactions with the world's shortcomings are whining or being a know-it-all. Not every vision dear to the heart is a pathological hallucination. Within the physical and psychical dimensions, research scientists can discover "closed" systems that operate according to the rules of causality. But as soon as the spiritual dimension comes into play, which thanks to the unity and wholeness of the human is almost always the case, freedom comes into play alongside it. And freedom knows no fixed rules. Freedom resides beyond compelling causes. Freedom is open and receptive to the new, which can neither be predicted nor derived from what has come before – because otherwise it would not logically be "new". The spirit is the power which creates the new – this is and has always been the case with the human being "made in God's image", to use Biblical language.

Of course, in the mutual interpenetration of the various ontological dimensions of the human, the human spirit is not the sole ruler. To claim this would be to fall into a spiritualism which logotherapy takes care to avoid. Someone like Frankl, with his decades of experience in psychiatry and neurology, did not underestimate dependence on the somatic and psychic, and, in particular, on the workings of the brain. The psychophysical foundations of human existence are what enable spiritual phenomena in the first place (which does not necessarily mean that they produce them) and can therefore also make them impossible, for example in the case of unconsciousness and in disorientation by various causes. This is also the reason why human freedom (of will) varies in each instance and is "according to ability". However, freedom should not be underestimated. For example, in popular motivation theories there is often too much emphasis placed on instincts that drive human behaviour, or on acquired/learned behaviour that is blindly followed; thus there is a failure to recognise that a spiritually endowed being has an ineradicable yearning for meaning and is attracted to values to which it devotes itself freely, if at all.

Need satiation and intention

The intentions of the nous specifically rise above the satiation of needs towards which all almost all the undertakings of living beings strive in order to secure the preservation and continuation of life. According to philosophical insight, the spirit cannot get sick or die, but its expression can be thought of as "made impossible", just as lamplight is not mortal per se, but no longer emerges from a broken bulb. As an entity beyond death and destruction, it is only logical that the spiritual is not directed towards its own preservation and continuation, which is guaranteed anyway. What is it directed towards, then? Towards an encounter with meaning and values, according to Frankl – towards surrender to them and service to them, towards the "illumination" of reality, just like the literal illumination provided by the lamplight of the metaphor.

This all mixes colourfully together in people. On the one side there are physical and psychic needs and the call for their satiation. One who is thirsty wants to drink. One who is angry wants to complain. This is completely legitimate and according to nature. On the other side there is the spiritual seed of what Frankl called the will to meaning, which points beyond one's own self.

The person who loves the flowers in a garden wants to water them to protect them from drying out. The individual who loves his or her family speaks respectfully with them, even when annoyed, not wanting to hurt them. In both cases, "wanting" is what holds things together, but the goal lies in opposite directions. The goal of any need fulfilment is the maintenance or restoration of one’s well-being. The goal of a drive is its own elimination, as Frankl pointedly noted. Drinking quenches thirst. Complaining takes the burning edge off of annoyance. In contrast, the goal of the discovery and fulfilment of meaning has nothing to do with the attainment of one's own wellbeing nor with the driving away of ill-being. It doesn't apply to the self, but to a "non self-ish" other. The flowers, the family … perhaps the self benefits from these goals, but perhaps it does not. Maybe it is happy about the beautiful flowers. Maybe it groans and sweats while it waters them. Maybe it is proud of a calm discourse with its family. Maybe this feels like miserable hard work. Whatever the situation, meaning doesn't question it. Within the framework of what is reasonable for an individual, its standard of measurement consists of the realizable values in the external world outside the self. And it would be pure reductionism to claim that solely self-centered motives control human action: that, in actuality, the flower lover only thinks about him- or herself and wants to impress the neighbors with a well-tended garden, or that the respectful communicator is really nothing but a fugitive from conflict who doesn’t dare to speak openly.

The potential for freedom (of will)

As mentioned earlier, the potential freedom of will is one of the premises of logotherapy. A second premise is the will to meaning. Both of these are needed to establish the existential responsibility of the human being. No one can be held responsible for wrong decisions without possessing the power of choice and – if this power exists – having an awareness or a feel for what he or she should choose in the name of logos. There are certainly stages of development, diseases, and disabilities, that on a permanent or temporary basis compromise individuals' spiritual freedom and recognition of meaning. There is no need for a debate amongst social scientists about this. What always triggers such debates, however, is the reverse situation, namely the question whether "normal" mature people actually possess freedom and recognition of meaning. The young Frankl had to engage with the deterministic view of human nature prevalent in his time, which on the basis of psychologising considerations built up the image of a "homunculus" so controlled and steered by unconscious impulses that it had practically no independent voice. At that time the unconscious was considered to be the exclusive domain of the drives, so that there was no place in it for meaning and values.

Today, the generation of Frankl's successors is once again confronted with deterministic trends; this time, however, based more on neurophysiological considerations. For example, the mirror neurons are responsible for empathy – people who don't have enough of them behave pitilessly and without consideration for others. As a result, the responsibility of criminals for their acts is a thing of the past. But what about sadists who specifically enjoy inflicting harm on other people? Without mirror neurons could they even know what those other people suffer for the sake of their enjoyment? The same applies to overinterpretations of the body's endorphins, which are responsible for feelings of pleasure. If their production is underdeveloped, there is automatically a significant increase in the appetites of the affected person, which are steered in unethical directions – this is the opinion of some neurophysiologists, for whom "evil deeds" are just "accidents of nature".

In Evil as the Price of Freedom, Rüdiger Safranski puts forward arguments which lean heavily on Frankl's theses of over 70 years ago. Thus, like Frankl, he establishes that determinism confuses the causes of an event with the reasons for human action, or at least throws them together in the same pot. He states:

Causes and reasons are fundamentally different phenomena. One is causality in the strict sense, the other is – as Kant put it – causality born out of freedom … The physiological understanding of humans sets itself the task of exploring what nature does to people. Pragmatic understanding sets itself the task of exploring what a person can or should make of him or herself as a freely acting agent. Seen from the outside there is causality, but experienced from the inside there is freedom. We act now and will always be able to find a causal explanation for our action afterwards. But at the moment of decision it doesn't help us to know that we are dependent on the physiology of our brain. We can't say to our brain: "Well go ahead and decide!" We have to do this ourselves as people. We don't just see ourselves as beings caught up in a chain of causality, we experience ourselves as beings who can act: impulsively, habitually, with calculation, and so on. This is what Kant fittingly called the "causality of freedom" … Freedom presupposes that man is a spiritual being …

The spiritual as movement of being

Let us leaf through what else Frankl has gathered together about the human spirit, the source of freedom and awareness of meaning. We have already mentioned that it is not synonymous with intelligence, or with rationality and intellect. Cognitions and emotions are (psychic) tools of the spirit, which it freely uses for purposes which are either meaningful or anti-meaningful. These purposes, the intentions of the spirit, the goals within being itself towards which the spiritual is directed, are what is truly interesting, because they are essential. All spiritual being is drawn towards other being: it is only truly "with" itself insofar as it is simultaneously "with" other being; a complicated situation. According to Frankl, this is the spirit's true natural wealth. When someone values someone else, he or she will move towards this person in spirit, will be spiritually near, will linger with him or her. If a person occupies him or herself with the history of the Middle Ages, then he or she is spiritually immersed in the time period of the Middle Ages and is "with" the character and events of that time. If someone listens avidly to a concert, then he or she is spiritually "with" the sound of the music that is currently being played. If someone is carefully investigating chemical samples in a laboratory, then he or she is "with" the results that are being worked on. If a person prays, then he or she is "with" God. We move towards the contents of our love, our belief, our hope, our interest, our selfimposed task, our joy – not in space but in being. As Frankl eplained, to "be with" is simply one's personal way of being: "The I becomes I only in the you."

Sometimes, however, we move away from all of these things spiritually: we turn away from dignity and value; we distance ourselves in spirit from truth, beauty, goodness; we live in a state of alienation from God and the world. But even hatred is an intentional phenomenon. Someone who rejects and dismisses the "being with" another being so strongly that he or she would like to remove, erase, destroy the other, discovers that a punishment follows closely. Hatred binds the hater with the object of hate as with red-hot iron rings. Paradoxically, the hater doesn't escape from the hated person, but flounders involuntarily in self-negation. Only with the help of conciliation and compassion summoned through the defiant power of the human spirit can the person escape. Indeed, hatred is not the opposite of love, but a hideously deformed variant of spiritual "being with", whereas indifference is the true opposite of love: a spiritual turning away from a being who has no significance for the person who turns away.

Inadmissible anthropomorphisms

Just as human love can't simply be derived from the sexual drive, we see that human hatred can't simply be explained by the aggressive drive unless we make ourselves guilty of projecting the three-dimensionality of the human onto the two dimensions of mere animal existence. Love and hate have to do with valuations, with upgradings and downgradings in which emotions are admittedly heavily involved, but which extend beyond the realm of emotion. They are existential acts, and, as such, specifically human. A male bird that attacks a rival doesn't hate him. A mother bird who feeds her chick doesn't love it. However, in both cases it looks exactly like this from a human perspective because we inevitably see nature through human eyes. But one can only understand beings on the same level as oneself, with the corollary that equality is interpreted into non-equal beings, as Frankl warned us in connection with the countless anthropomorphisms (erroneous attributions of humanness) of which we are constantly guilty. Without any idea of its wisdom, birds carry out a wise program that evolution has engraved into their genes, and which is initiated by particular triggers. In animal experiments, the male will attack dummies if they send out electrically induced threatening stimuli. And they cuddle with real rivals whose attack signals are artificially suppressed. The female will feed balls of wool when they chirp like hungry chicks. And they ignore their own chicks if they are prevented from chirping.

Not that we, as humans, are not also subject to the dictates of our genes, or that countless motors cannot be initiated (or suppressed) in us by triggers. Our human spirit, however, allows us to react to them in a differentiated manner. In this small room for manoeuvre first brought into being by evolution, an agency of orientation appears which would not be perceptible where this room does not exist (as in the case of birds), because it would be meaningless. The wisdom that has programmed all life, but which has breathed an additional choice into human life, lights up. It lights up – and can be received on the fine antennae of our conscience.

The threefold perceptivity of conscience

Frankl engaged intensively with the phenomenon of conscience. In logotherapy the ancient maxim – that life cannot fail so long as a person for the most part follows his or her conscience – comes to fruition for psychotherapy. The conscience, as a human organ of meaning, can admittedly be wrong, but nevertheless it has been and remains our most reliable standard of measurement, more certain than all codes of behaviour that invoke rights, morals, rules or traditions. It is our innermost and most honest "meaning organ", even if we are sometimes inclined to suppress or override it. The conscience can be decidedly bothersome, because it resists all attempts at corruption and sticks out even from under a thick carpet of lies that one unfolds for one's own assuagement. It is a perceptive faculty that can reveal things even through closed spiritual eyes.

Free will allows us to keep a lookout for everything that we can, want to, are allowed to, should decide for ourselves. The will to meaning allows us to keep a lookout for the one thing that we should decide for ourselves right now. The conscience is able to discern this one thing. Frankl divided up the topic of the perceptive faculty of the spiritual unconscious – also called intuition – and explained it in a threefold way. The hallmark of such a spiritually unconscious perception, whose image eventually rises into the consciousness, is that what it has in its sights is not the real, but only the possible. However, seen from a higher vantage point, this possibility is a necessity; in other words it concerns a potential that is worth making actual. But how could something be made real if it was not first spiritually anticipated? This is exactly what the conscience achieves: it doesn't see a being but a should be.