5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

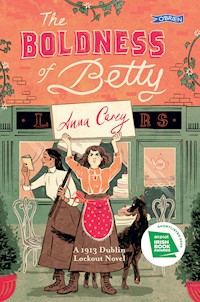

- Herausgeber: The O'Brien Press

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

Mollie Carberry is a suffragette! Well, sort of. Mollie and her best friend Nora have been bravely fighting for women's rights – even though no one else really knows about it. But when they hear a big protest is being planned, they know they have to take part. If only they didn't have to worry about Nora's terrible cousin, her awful brother and her neighbour's very annoying dog … An engaging story about a strong and intelligent girl fighting for the right for women to vote. WHEN DID IRISH WOMEN GET THE VOTE? The Representation of the People Act 1918 became law on 6 February 1918. It gave the vote to virtually all men over 21, and women over 30 who met certain requirements. In November 1918 an act was passed which enabled women to stand for parliament in the forthcoming elections. The only woman to win a seat in parliament across England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales in December 1918 was Constance Markievicz, who was elected by the people of south Dublin but who did not take her seat. In 1922, the new Irish Free State gave the vote to all women over 21, finally giving Irish women the same voting rights as Irish men.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Praise for Other Books by Anna Carey

The Making of Mollie

‘I loved Mollie – she is rebellious … thoughtful and funny.’

thetbrpile.com

‘A girl’s eye view of early feminism … exciting, vivid … with the impulsive and daring Mollie.’

Lovereading4kids.co.uk

‘A historical novel with a contemporary edge.’ Sunday Business Post

The book is set in Dublin, 1912, when Home Rule was being lobbied for, and women were arguing that the vote should be for all. The plot revolves around the irrepressible Mollie becoming both politically aware and active. The family servant, Maggie tartly sums up her own shaky existence, ‘I may very well be part of the family, but it’s a part that can be sent packing without a reference.’ I … curled up on the couch and did not put it down.’

Historical Novel Society Review

‘For junior feminists … a must-read.’

The Irish Times

‘Carey brings to life Mollie’s struggles in a way that makes the book strikingly relevant to the teenagers of today. A historical novel with a contemporary edge.’

Sunday Business Post

‘A cracking book.’

Irish Independent

The Real Rebecca

‘Definite Princess of Teen.’

Books for Keeps

‘The sparkling and spookily accurate diary of a Dublin teenager. I haven’t laughed so much since reading Louise Rennison. Teenage girls will love Rebecca to bits!’

Sarah Webb, author of the Ask Amy Green books

‘This book is fantastic! Rebecca is sweet, funny and down-to-earth, and I adored her friends, her quirky parents, her changeable but ultimately loving older sister and the swoonworthy Paperboy.’

Chicklish Blog

‘What is it like inside the mind of a teenage girl? It’s a strange, confused and frustrated place. A laugh-out-loud story of a fourteen-year-old girl, Rebecca Rafferty.’

Hot Press

Rebecca’s Rules

‘A gorgeous book! … So funny, sweet, bright. I loved it.’

Marian Keyes

‘Amusing from the first page … better than Adrian Mole! Highly recommended.’

lovereading4kids.co.uk

‘Sure to be a favourite with fans of authors such as Sarah Webb and Judi Curtin.’

Children’s Books Ireland’s Recommended Reads 2012

Rebecca Rocks

‘The pages in Carey’s novel in which her young lesbian character announces her coming out to her friends and in which they give their reactions are superbly written: tone is everything, and it could not be better handled than it is here.’

The Irish Times

‘A hilarious new book. Cleverly written, witty and smart.’

writing.ie

‘Rebecca Rafferty … is something of a Books for Keeps favourite … Honest, real, touching, a terrific piece of writing.’

Books for Keeps

Rebecca is Always Right

Fun … feisty, off-the-wall individuals and a brisk plot.’

Sunday Independent

‘Be warned: don’t read this in public because from the first sentence this story is laugh out loud funny and only you’ll make a show of yourself … this book is the funniest yet.’ Inis Magazine

‘Portrays a world of adolescent ups and downs … Rebecca is at once participant in and observer of, what goes on in her circle, recording it all in a tone of voice in which humour, wryness and irony are shrewdly balanced.’

The Irish Times

To all the women still marching for our rights in Ireland today.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to everyone at the O’Brien Press, especially Emma Byrne and my ever-patient and supportive editor Susan Houlden; Helen Carr for being generally encouraging; Lauren O’Neill for another wonderful cover; everyone who generously spread the word about Mollie, especially Marian Keyes, Claire Hennessy, Nina Stibbe, Sarra Manning and Sarah Webb; Nicola Beauman of Persephone Books; the historians without whose work I couldn’t have written about Mollie’s adventures, Rosemary Cullen Owens, Margaret Ward and especially Senia Paseta. Any historical errors are, of course, entirely my own; the extended Carey and Freyne families; and Patrick, for making me laugh and keeping me going.

Contents

HISTORICAL NOTE

This book is set in Dublin in 1912. At the time, Ireland was part of the United Kingdom, but there was a big demand in Ireland for what was called Home Rule. This meant that Ireland would be part of the UK, but would have its own parliament in Dublin. In 1912, the only people who could vote in general elections in the UK were men (and not even all men – only men who owned or lived in property of a certain value). Lots of women, however, were campaigning for the vote, and they were known as suffragists or suffragettes. In June 1912 several members of the Irish Women’s Franchise League broke windows of various government buildings as an act of protest.

25 Lindsay Gardens

25 Lindsay Gardens, Drumcondra, Dublin.

21st June, 1912.

Dear Frances,

I AM NOT IN PRISON

I know this sounds awfully dramatic, but I last wrote to you just after Nora and I had broken the law as daring suffragettes, and since then I’ve rather been caught up in revising for exams and things. So I thought you might have been worrying about us. But I am happy to say that we are still free.

Or at least, we are not in prison, like the brave suffragettes who broke windows all over Dublin last week. I know Nora and I are very lucky not to be languishing in a jail cell right now, but I must admit that I don’t feel very free. We still have a couple of exams left to do, and when I’m not studying my mother keeps making me do all sorts of stupid chores. This is particularly unfair as Harry, who also has exams, doesn’t have to do his usual task of helping Maggie with cleaning the boots. (This is literally the only thing he ever has to do, and it’s barely a chore at all as he actually LIKES mucking about with boot blacking, and besides, at this time of the year, there’s hardly any cleaning to do because the streets aren’t muddy, just dusty.) What with the studying AND all the mending I barely have a moment to think. In fact, I’m worried I might come down with a brain fever from overwork. Though when I told Mother this before school this morning she just laughed cruelly.

‘I don’t think there’s much chance of you working yourself into any sort of fever,’ she said, callously. Then she must have felt a bit guilty because she said, ‘But I suppose I could let you off the mending this afternoon. Just this once.’

‘Thank you so much,’ I said, very sarcastically, but she didn’t seem to realise I was being sarcastic because she said, ‘You’re welcome.’

So anyway, that’s why I’m upstairs lying on my bed writing to you right now, instead of downstairs sewing buttons onto Father’s shirts, which is what I was meant to be doing this afternoon. Father is stuck in the office working on some dull bill or other so I am not missing the latest installment of his epic novel. Hopefully he will read it tomorrow evening.

I haven’t told you much about his novel recently, have I? It’s still very exciting. The brave hero Peter Fitzgerald is pretending to be a German spy, but unfortunately he can’t really speak German so he has to say ‘ja’ and ‘nein’ to everything and hope for the best. That means ‘yes’ and ‘no’, in case you don’t know. Those are pretty much the only German words I know – they teach German in my school, but you have to choose between it and French and I chose French. I think it would be good to learn both, then if you had to pretend to be a spy (or if you actually were a spy), you would have more options. I’ve always thought being a spy sounds awfully exciting. Phyllis has accused me of spying on her often enough so maybe I have a natural talent for it. In fact, perhaps I should learn Russian too, just in case. Russian spies are always cropping up in books.

Anyway! I am so sorry you won’t be coming to Dublin this summer. You could have joined in my and Nora’s suffrage activities! I don’t know if we will paint any more postboxes though. Just painting one postbox was terrifying enough. But we will do something, especially as the Prime Minister is coming to visit Dublin next month, and there will definitely be some sort of protest then. And in the meantime, we will try and go to more meetings. Of course Phyllis is refusing to take us to any, especially since the brave women from the Irish Women’s Franchise League got arrested for breaking windows.

‘Anything could happen now,’ she said. Remember, we had both been at that big meeting in the Phoenix Park a few days after the women got arrested. Loads of protestors turned up and yelled horrible things at the suffragette leaders, and the police had to step in when the mob started pushing and shoving them. That was bad enough, but Phyllis seemed to think that things would only get worse.

‘And,’ she said, ‘I won’t be able to keep an eye on you and Nora if things get dangerous.’

As if we couldn’t take care of ourselves! She’s being so unfair. She needs us at meetings, if you ask me. If it weren’t for us, she’d have been caught holding a banner at that Phoenix Park gathering a few months ago. After all, me and Nora were the ones who told her that Mother’s friend Mrs. Sheffield was passing by. And what thanks did we get for that? None! She didn’t even buy us a bun in the Phoenix Park tearoom afterwards. We had to buy our own. She’s so ungrateful. I told her this and she didn’t even have the good grace to look ashamed of herself.

‘I never asked you to come to that meeting,’ she said. ‘And you needn’t look so martyr-ish. You only found out about the movement in the first place because you were sneaking around spying on me.’

This was true, I suppose. But still!

‘Besides,’ Phyllis went on, ‘you’ve talked me into taking you to enough things already.’

I was going to remind her that when she actually took us to the biggest suffrage meeting that ever there was, her stupid friend sold our tickets and we had to sit in the vestibule outside the concert hall for about five hours. But I didn’t get a chance to mention it because she immediately marched off into the drawing room where Mother was sitting with Aunt Josephine. I think she only went in there to avoid talking to me, as no one would ever join Aunt Josephine voluntarily. Poor Mother doesn’t have a choice, because Aunt Josephine just turns up at the house whenever she feels like it, whether she’s invited or not (which she hardly ever is).

Phyllis should remember the movement needs all the support it can get at the moment because the IWFL heroines finally had their trial yesterday. Phyllis wanted to go along to support them, but Mother had made an appointment at the dressmaker to get some new summer frocks fitted, and Phyllis couldn’t think of a convincing excuse to get out of it. But her friend Mabel went to the court and she came over yesterday evening to tell Phyllis all about it. I already knew that Mabel had planned to go to the trial so when she called to our house and Phyllis took her straight upstairs to her room, I knew what they’d be discussing. And so – and this is NOT sneakish, Frances, I wasn’t spying on them – I followed them and knocked on the door.

‘Go away,’ said Phyllis, without even bothering to open it.

I opened it myself and stuck my head in. ‘Please let me hear what happened at the trial,’ I pleaded. ‘You know you can trust me not to breathe a word.’

‘Oh go on, Phyl, let her stay.’ Mabel gave me an apologetic smile. ‘I still owe her for that business at the big meeting.’

If you recall, it was Mabel who sold our tickets to someone else.

Phyllis sighed.

‘Very well,’ she said. ‘But promise me you’ll just sit quietly on the floor and won’t interrupt.’

‘I wouldn’t dream of it,’ I said, and I sat down on the floor in a very dignified manner.

‘So, Mabel,’ said Phyllis. ‘Tell us all.’

Mabel took a deep breath.

‘Well,’ she said, ‘the bad news is they got two months.’

Two whole months! In a horrible dank prison, full of black beetles and other horrid things. I thought of the terrible bits about prison in No Surrender, that book about English suffragettes.

‘They won’t force feed them, will they?’ I said.

‘It depends on whether they go on hunger strike,’ said Mabel.

I hoped they wouldn’t, for their own sakes. They do awful things to women who go on hunger strike. They shove mashed-up food down their noses and throats with a rubber tube, which sounds like utter agony. I read that some women can barely speak after they are released.

‘How did they seem?’ said Phyllis. ‘In the court, I mean.’

‘Jolly cheerful, actually,’ said Mabel. ‘Mrs. Sheehy-Skeffington had two huge bouquets of flowers with her. And they all seemed pleased so many of us were there to support them. I heard someone say there were nearly two hundred suffragettes in the gallery.’

‘Gosh,’ I said.

‘Even the judge seemed quite sympathetic,’ Mabel went on. ‘He said they were ladies of “considerable ability” and he didn’t seem particularly keen on having them there at all. But I suppose once they had been caught and admitted what they’d done, he had to give them some sort of prison sentence.’

‘So there weren’t any Antis in the court?’ asked Phyllis.

Mabel shook her head. ‘I didn’t see any,’ she said. ‘Everyone seemed terribly supportive. And the ladies themselves were simply marvellous. When they were being led off, Mrs. Palmer cried “Keep the flag flying!” And we all cheered and cheered.’

‘Oh, I do wish I could have gone, instead of standing in a stupid dressmaker’s being poked with pins for hours,’ said Phyllis longingly.

‘And Mrs. Sheehy-Skeffington gave an awfully good speech,’ Mabel continued. ‘She pointed out that a man had got a shorter sentence that morning for beating his wife than they’d been given for breaking a few windows. And then she reminded us all that they might be going to jail, but that the rest of us were free and we had to remember that the Prime Minister is coming over in July.’

‘There aren’t any fixed plans for his visit yet, are there?’ said Phyllis. ‘I mean, no special meeting or anything.’

‘I don’t think so,’ said Mabel. ‘Mrs. Mulvany was saying something about making banners and posters and things to greet him on his way into town from Kingstown. But I don’t think anything’s been decided yet.’

As soon as I heard this, I decided that me and Nora must find some way of taking part in the protests. I’m not sure the IWFL would let us hold an official IWFL banner (I know Phyllis wouldn’t), but I don’t see why we couldn’t march along behind one. Or even make one of our own.

I knew better than to mention this straight away, though. Phyllis would only tell me it was too dangerous. She’s always convinced something really awful and violent will happen, and as far as I can tell it never does. Even the rowdies at that last meeting weren’t too frightening (though I suppose the police did step in before they could go too far). Whatever happens I am ready to face it for the cause. Besides, as you know, I can run pretty fast, so if the Antis did start throwing cabbages and things I’m sure I’d be able get away before I got hit by one. At least, I hope so.

I am sad that you won’t be coming over here this summer, but how exciting that you are getting to visit America! Will you get to go to the place where Little Women is set? I remember Professor Shields telling us that it’s somewhere in New England. I love that book, even though the March sisters are a lot more devoted to their mother than I am to mine. They never really complain about her making them sew on buttons. Maybe Americans are all more saintly than we are. Please find out and report back.

Part of me wishes that we were going away somewhere exciting and novel for the whole summer like you, but another part of me is glad that I won’t miss out on any suffrage activity, especially with Mr. Asquith coming over. And we will get to go on our usual holiday to Skerries in August, which isn’t particularly exciting but is always good fun, especially when the weather is nice. We can swim in the sea and go and look at the boats and spot seals. Harry says he’s going to hire a boat and row over to one of the islands off the coast all by himself ‘to get away from all you women’, but I bet he won’t. It’s just more of his usual boasting. I don’t think he even knows HOW to row a boat.

I suppose I should go and learn some French verbs now, not that I want to. Oh, writing about verbs reminds me, in your last letter you asked how Grace Molyneaux had been carrying on since she threatened to tell Nora’s parents about me and Nora being suffragettes. Well, I am pleased to inform you that she has kept her word about not telling. In fact, now that the exams are about to begin she is in a complete frenzy, because this is her last chance to win the Middle Grade Cup, with which of course she is totally obsessed. She spends all her lunchtimes with her nose in her special study notebook which she guards with her life.

She probably will win the stupid cup at this rate, which will make her worse than ever (if that’s possible – perhaps it’s not). I still hope Daisy Redmond gets it. Daisy studies because she likes learning things, not so she can lord it over everyone else like Grace does. And Daisy’s been working very hard even though her mother has been very sick recently and she hasn’t been able to see her because she (Daisy) is a boarder and her parents live in Waterford. So she definitely deserves something good happening to her. But anyway, in the meantime Grace seems more interested in studying than tormenting me and Nora, which can only be a good thing.

I am going to send this letter first thing tomorrow. Good luck in your own exams! I hope I do well in mine, if only because if I don’t Mother and Father will probably force me to study all summer and then I won’t be able to do any suffragette things.

Best love and votes for women Mollie

30th June, 1912

30th June, 1912.

Dear Frances,

This is not going to be a long letter because I want to make sure you get it before you head off to America. I am pleased to say that I am FREE. Yes, I have survived my exams, and they weren’t actually that bad apart from Historical Geography, where I made an utter hames of explaining how a glacier is made. But the rest were all right, and in fact I actually did very well in English, so hopefully my parents will remember this success next term when they’re going on about how I need to study more.

Harry, of course, made a huge fuss about his own exams, demanding tea and toast at all hours of the evening ‘to fuel my brain’ during his studies. And what’s worse is that he actually GOT it. No one brought me any brain fuel when I was studying, but then I suppose I didn’t ask for it, because I’m not a baby like him. Honestly, you’d think he was working to become a doctor or something, the way he carried on, instead of just a boy doing some summer tests. He’s finished now too. He and his friend Frank came round to our house for a celebratory tea today after their last exam, though in fairness to my mother, I must say that she gave me a celebratory tea yesterday after my exams had finished. For once, Harry did not get preferential treatment.

For both teas there was a special lemon cake made by Maggie. Maggie is a much better baker than any of the rest of us. Mother sometimes says she worries that Maggie will get fed up of working for our family and will go off and start her own bakery and make cakes all day, which I must say sounds like a better job than sweeping our floors and chopping vegetables for our dinners. But when I said this to Maggie – adding that of course I would miss her very much if she went off to make cakes – she said that it was a nice idea, but she’d never have the money to start her own bakery. Which is rather unfair, but on a shamefully selfish level I am quite glad she won’t be leaving us any time soon, because I do love her.

Sorry, I got distracted there. I find this often happens when I’m trying to tell a story. I start off writing about one thing and then I think of something else, and before I know it I’ve gone off on what in geometry class we call a tangent. I will try to stick to the point for the rest of this letter. Although now I’m not entirely certain what my point was.

Oh yes! I was talking about Harry and Frank. Well, there is quite interesting news on that front which is that Frank is coming to stay with us. Yes, he will be staying in our house for just over a week in July. His parents are going to visit an elderly aunt who lives somewhere in Kerry and apparently she (the aunt) can’t abide having children in the house. Frank’s father tried to explain that Frank wasn’t exactly a child anymore and was quite capable of being quiet, but the aunt didn’t care. She sounds worse than Aunt Josephine. Frank says that his parents want to stay on her good side because apparently she is quite rich, and they hope she’ll leave them something when she dies, though they will never admit this to Frank. So they decided that he could stay with another (nice) aunt and uncle in Meath. And Frank wasn’t particularly looking forward to it as his cousins are all much, much younger than him.

When Harry heard this, he asked our parents if Frank could stay with us instead and they said yes. I told Nora this yesterday and she looked at me in an extremely irritating way.

‘So he’ll be there for ten whole days,’ she said. ‘Maybe he will finally declare his love.’

I hit her with a pillow. (We were sitting on her bed at the time.)

‘Shut up Nora Cantwell, you vile creature,’ I said. ‘He won’t do anything of the kind. And I hope you’ll drag your thoughts out of the gutter while he’s staying in the house.’

‘I was only teasing,’ said Nora. ‘To be perfectly honest I think it’s more likely that you’ll declare your love to him.’

So of course I had to hit her with a pillow again, and she fell off the bed, which shut her up. That was a few days ago, and she hasn’t come out with any more rubbishy nonsense since, so I hope she has decided she’s not going to subject me to vulgar teasing. She does still keep giving me significant looks whenever Frank’s name is mentioned, but she’s been doing that for a while anyway so it doesn’t really bother me anymore.

It will be rather strange having Frank in the house all the time, though, especially as it’s the holidays so we’ll be free all day. (Well, free when Mother isn’t expecting us to do tedious chores, and by us I mean me and Phyllis and Julia because Harry does barely anything.) But Frank’s not coming until the week after next (I think) so I suppose I have plenty of time to get used to the idea.

And there is even more good news: Grace Molyneaux didn’t win the Cup! Daisy Redmond won it instead. I was very happy about this, not just because I hate Grace (although I must be honest, I do a bit). But Daisy deserved it AND when she got the prize she was very happy and didn’t lord it over the rest of us at all, which we all know Grace would have done.

Unsurprisingly, Grace was not a good loser. When Mother Antoninas announced the winner Grace looked so horrified I actually felt sorry for her for a moment. (I was quite surprised by that, but it turns out that sometimes seeing your enemies humiliated and miserable gives you a strange sort of wormish feeling in your stomach and you can’t enjoy it at all, even if you thought you would beforehand.) After the prize giving was over and we all went to the refectory for milk and buns, Grace ran away to the lav and when she came back she looked like she’d been crying. Even Nora looked a bit uncomfortable when she saw that.

‘I know I wanted this to happen,’ she whispered to me and Stella. ‘But she does look rotten.’

But just as we were all starting to feel sorry for Grace, she marched up to Daisy and unintentionally reminded us why we’d been yearning for her downfall. At first I thought she was going to congratulate her successful rival, which would have been very gracious for Grace (living up to her name, for once). But no! She folded her arms, tossed her curls and hissed, ‘I suppose you think you’re very clever.’

Daisy looked quite startled.

‘Not particularly,’ she said.

‘You know they only gave you that cup because they felt sorry for you,’ said Grace. ‘Because of your mother.’

I knew Grace was capable of dealing low blows, but this was very low, even for her. Daisy’s face went very white and she ran out of the room. For a moment no one said anything, but then Stella ran over to Grace. I’ve told you before that Stella can be a tigress when roused, especially for a good cause. Well, if looks could kill, Grace would have been lying stone dead on the refectory floor.

‘You utter beast,’ she said furiously. ‘Didn’t you know Daisy got a telegram this morning? Her mother’s much worse. Daisy’s going straight home after lunch. Sister Henry’s taking her to the station. And the only reason she hasn’t left already is because there isn’t a train until three.’

Grace obviously has some human feeling left because she looked pretty guilty when she heard that.

‘Well, how was I to know?’ she said. And before Stella could say anything else to her she marched over to a seat in the corner of the room with her plate of buns. Her faithful follower Gertie went after her. But May Sullivan, who you probably remember has been hanging around them since she started at the school earlier this year, didn’t follow them.

In fact, ever since the day when Grace threatened to tell our parents about our suffrage activities and Stella showed us how ferocious she could be when it comes to important things, May has been spending more time with other girls in the class. She’s become friendly with Nellie Whelan and Mary Cummins, who are jolly decent and who are both supporters of our suffrage cause. When Grace marched off, Nellie had already taken a seat next to Johanna Doyle, and May went over there and asked if she could join them. I really think she might have finally had enough of Grace. Hopefully when we come back in September she will have totally escaped her former friend’s clutches.

It seems so strange that we won’t see lots of our classmates for months and months (well, two months). I know we’ll see some of the girls who live in our part of Dublin, and poor Nora will probably be forced to see Grace at some stage, seeing as she’s her cousin, but all the boarders will be scattered all over the country and in some cases beyond – there are a few girls who come over from Scotland. I shall miss Stella terribly, she has been simply marvellous this term. I can’t believe I ever compared her to a white mouse. It was awfully sad saying goodbye on the very last day. Nora and I had to promise to write every week, which of course we will.

‘And do let me know …’ Stella’s voice dropped to a rather loud whisper. ‘If you do any suffragette things. I’ll be cheering you on from Rochfortbridge.’ That is the name of the nearest town to Stella’s family house. At least, the house they live in at the moment. Her father is a bank manager and they have lived in quite a few places. I’m not sure why bank people seem to move around a lot but they do. It’s rather like being a diplomat – you get posted to exotic environs.

‘If we commit any more crimes for the cause,’ said Nora solemnly, ‘we will wear our suffragette scarves in your honour.’

Stella, in case you’ve forgotten, knitted wonderful scarves for me and Nora in the IWFL colours. It was nice of Nora to promise to wear them, but I couldn’t help thinking it might be a bit warm if we do anything in July. Anyway, the more I think of it, the more I feel I don’t actually want to break the law again. Every time I think of Mrs. Sheehy-Skeffington and the other ladies languishing in their prison cells I feel a bit sick. And then I feel a bit cowardly because really, I should be prepared to do anything for the cause, including breaking the law. But I don’t want to go to prison if I can help it.

Our IWFL heroines are not on hunger strike like the poor English suffragettes, so thankfully they haven’t been force fed or anything like that. But it must be extremely horrid to be locked up in a nasty jail, all because they were fighting for their rights – for all of our rights, I should say. I shall pray for them tonight. (After all, Jesus did talk about visiting prisoners being a good thing, so praying for them can’t be wrong, can it?)

I hope your journey to America goes safely. It sounds very exciting to me. I do understand why you feel a bit nervous – I bet I’d keep thinking about the Titanic too – but really, how likely is it that TWO ships will be hit by icebergs in just a few months? Now I’ve written that sentence down it doesn’t look very consoling, but you know what I mean. Ships cross the Atlantic all the time and practically all of them get there safely, so I’m sure you will too. Phyllis’s friend Mabel went to visit relatives who live in Boston a few months ago. (They are very grand, much more so than anyone we know here, and live in a giant sort of house Phyllis called a brownstone, which I imagined being rather like a castle, but which according to Phyllis is just an ordinary big terraced house.)

Anyway, Mabel got there and back quite safely, and Phyllis says she had a jolly good time on the boat so I am sure you will too. Apparently Mabel’s cabin was very nice and there was a dear little round porthole, through which she could gaze out at the vast ocean, though she felt rather guilty whenever she caught a glimpse of the poor people down in third class, which wasn’t nearly as comfortable. I don’t think they even have portholes down there. Maggie’s cousin Bridie went to America a few years ago by third class and she arrived safely too – but she hasn’t come back and Maggie says she never will.

‘What has she got to come back to here?’ said Maggie, when I asked about Bridie the other day. ‘She’s got a good job in a nice little hat shop in New York now.’

‘Do you hear from her often?’ I asked, handing Maggie a tea towel. She was putting away some dishes in the kitchen at the time. Maggie shook her head.

‘She’s not a great one for writing,’ she said, carefully drying her favourite teacup. (It has strawberries on it, and Julia gave it to her for her birthday a few years ago.) ‘But she sends me a card every Christmas so I know she’s still alive and well.’

‘Do you think she might ever get home for a visit?’ I said.

‘Goodness, no,’ said Maggie, putting the cup on the dresser shelf. ‘She’d never be able to afford the journey here and back. No, she’s over there forever now.’

It seemed awfully sad that Maggie’s cousin will never see her family again, but Maggie pointed out that lots of people leave Ireland and never come back.

‘So there’s no point in crying over it,’ she said. But I still think it’s sad. I know I complain about my family a lot, but I couldn’t bear the thought of going to the other side of the world (well, almost) on my own and never seeing any of them again. Even Harry (not that I would ever admit that to him). I suppose I wouldn’t mind if Aunt Josephine went to America and never came back, but I don’t think that’s very likely to happen.

Do write before you get on the boat, and if you don’t have time, maybe you could write me a letter once you’re actually on it – Mother said that sometimes you can send letters from steamships because little boats call in and take letters back home. Imagine getting a letter that was sent from the middle of the Atlantic Ocean! What would the postmark be? Mother was a bit vague on the details so she may be all wrong about this, but if it turns out you can send letters from the middle of the sea, please do send me one.

Also, I’ve been thinking of what you said about getting post once you’re in America, and I have come up with a solution. Why don’t I keep writing letters here and then send them all to you when you’re back in England? If I try sending them to all the places you’re visiting in America then I would probably keep missing you, but this way you will eventually have a full report on all the doings in Dublin. Of course, there may not be much to write – probably not anything as exciting as the last few months. But I will keep writing to you anyway, while you’re off in Boston and New York and New Orleans and all those other exciting places. And then you can read them all when you come back and have a record of summer in Dublin in 1912.

Much love and votes for women – and bon voyage, as we say in French class, Mollie

4th July, 1912

4th July, 1912.

Dear Frances,

I know you are on a boat right now and I wish I was there with you because something awful has happened. In fact, it’s so terrible I can barely bring myself to write about it. Don’t worry, no one has died or been horribly ill or been arrested (no one I know, anyway). But it is still pretty dreadful.

GRACE IS STAYING IN NORA’S HOUSE.

FOR AT LEAST TWO WHOLE WEEKS.

Remember when Harry had to come home from our cousins in Louth because one of them had scarlet fever? Well, Grace’s brother goes to boarding school in Louth and clearly there is some sort of terrible scarlet fever epidemic up there because he (the brother) arrived home for the holidays this morning and promptly came down with it as soon as he walked in the door, as far as I can tell. And Grace had been away visiting an aunt for the day and her parents had to telephone the aunt (so it turns out the Molyneauxs did have a phone after all, I always thought that was just Grace showing off) and tell her that Grace couldn’t come home.