Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Bedford Square Publishers

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

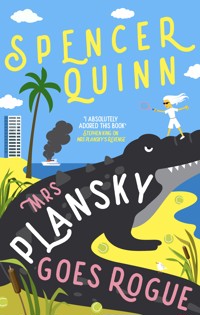

'I absolutely adored this book. Mrs. Plansky is a terrific character.' - Stephen King on Mrs Plansky's Revenge The irresistible and unforgettable Mrs. Plansky goes rogue in this whirlwind adventure that will lead her up and down coastal Florida and beyond! Mrs. Plansky is fresh off of winning a thrilling senior tennis championship with her doubles partner, Kev Dinardo, and is gearing up to celebrate with him on his yacht. That is, until the yacht is destroyed in a fire. Kev claims the fire was caused by a lightning strike, pure bad luck, but there's one small problem―Mrs. Plansky didn't see any lightning. Already certain there's more going on than she's being told, Mrs. Plansky's curiosity turns to concern when Kev goes missing. Her suspicion gets the better of her and leads her to break into his house, only to find it ransacked. But Kev isn't the only person Mrs. Plansky has to worry about. A conversation with her dad reveals that not long ago, he'd introduced Kev to Jack, Mrs. Plansky's wayward tennis pro son. And now, her dad―distracted by arrangements for his upcoming wedding―either can't remember or has no interest in divulging any details. Worse? Now Jack has gone missing, too.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 453

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

JOIN OUR COMMUNITY!

Sign up for all the latest news and and exclusive offers.

BEDFORDSQUAREPUBLISHERS.CO.UK

Praise for Mrs Plansky Goes Rogue

‘Loretta Plansky – and Spencer Quinn – are more charming and clever than they have any right to be. In Mrs Plansky Goes Rogue, our resident seventy-one-year old with an artificial hip is up against love, villainy, and exploding yachts. Quinn’s writing is Mercedes-smooth, carrying us through another caper with verve and delight’ Gregg Hurwitz, New York Times bestselling author

‘In her second adventure, Quinn’s heroine brings the same charm, humor, and sturdy constitution that readers enjoyed from book one. Mrs Plansky uses others’ perceptions of older people to her detecting advantage to find answers. Fans of Only Murders in the Building, Richard Osman’s ‘Thursday Murder Club’ series, and senior detectives in general will love Loretta and wish for many more adventures’ Library Journal, starred review

Praise for Mrs Plansky’s Revenge

‘I absolutely adored this book. Really fun but with a few teeth, as well. Mrs Plansky is a terrific character. The story ticks along like a good watch’ Stephen King

‘Mrs Plansky’s Revenge is a triumph that pits an original, memorable, and deeply human protagonist against a plausible threat, then takes us on an unexpected, thrilling, and satisfying journey. Heartfelt, thoughtful, and always suspenseful’ Michael Koryta, New York Times bestselling author of An Honest Man

‘Mrs Plansky is a wonderfully memorable heroine, full of wit and equally plausible as an ace tennis player and a motorcycle-driving detective with Romanian gangsters hot on her tail. Readers will be eager to see what Mrs Plansky gets up to next’ Publishers Weekly

‘Quinn’s briskly plotted nail-biter takes unexpected twists and turns that are nicely balanced by Mrs Plansky’s memories of her husband... Her age never becomes a detriment. Rather, she works it to her advantage, employing great ingenuity to solve a crime that elevates her into an immensely likable, wholly appealing heroine’ Shelf Awareness, starred review

For Seth, Ben, Lily, and Rosie, who mean so much

1

‘What’s your favorite sports cliché?’ said Kev Dinardo.

‘In general?’ Mrs Plansky said. ‘Or possibly useful at the moment?’

Kev turned to her and smiled, a sweat drop quivering on the end of his chin. They hadn’t known each other long, just a few months, mostly getting together on the tennis court, but it was enough for her to have learned he had two smiles: a big one when he was happy about something, which was often, and a small, quickly vanishing one that flashed when he was struck by an unexpected insight. This particular smile was the second.

Mrs Plansky searched her mind. Her background was not one of those sports-free backgrounds, so she knew many sports clichés, but now she came up empty. That was frustrating. This whole situation, taking place on Court #1 at the New Sunshine Golf and Tennis Club, was frustrating. Her face felt flushed, and not just from the exertion and the heat. Mrs Plansky loved playing tennis. She liked to win. She did not hate to lose. Her son, Jack, out in Arizona, a gifted player with professional experience on the satellite tour and now a teaching pro, hated to lose. He liked to win. Did he still love or had he ever loved playing tennis? She shied away from that question. What if he’d devoted his whole professional life to something he didn’t love? What kind of toll would that take? But this wasn’t the slightest bit relevant, not at the moment. What was relevant? The fact that although she didn’t hate to lose, she hated to lose like this.

‘Here are some,’ Kev said. They were on a changeover between games, sitting on a courtside bench. The sweat drop wobbled off his chin – a strong, squarish chin that might have been a bit much on some male faces but not his – and fell, somehow landing on her bare knee, cooling a tiny circle of her skin. ‘It ain’t over till it’s over. One play at a time. Go down swinging.’

Mrs Plansky was unmoved by any of them, especially the last. Over on the other courtside bench their opponents had set aside their energy drinks and were rising. Changeovers lasted forty-five seconds, but at club level events no one was strict about it, although the umpire in her chair did seem to be glancing down at them. Also the opponents, representing the Old Sunshine Country Club in this North Beaches Sixties and Over Mixed Doubles Championship match, were now on their feet and bouncing a bit, eager to get this – what would you call it? Demolition? Close enough. This demolition over and done. The two clubs were ancient rivals, ancient for this part of the world, going all the way back to the 1995 founding of New Sunshine. Old Sunshine dated from 1989 and had old Florida pretensions. Its members had to wear white on the court. Half white was the rule at New Sunshine: Kev, for example, now in white shorts and a crimson tee, and Mrs Plansky in a sleeveless peach-colored tennis dress with white trim perhaps making up ten percent of the whole, or not even. She could be something of an outlaw at times.

‘Just choose one,’ Kev said. ‘I hate to point it out, Loretta, but we’re running out of time.’

Mrs Plansky rose and picked up her racket. The opponents were striding onto the court, the woman, Jenna St. Something or Other taking her place at the net and the man, Russell Curtis or possibly Curtis Russell, heading to the baseline to serve. Neither of them looked older than forty-nine. They’d had work done, of course, but still. Mrs Plansky, too, had had work done, just the once a few years ago, on an afternoon outing with her daughter, Nina, down for a few days from her home in Hilton Head. A nice mother-daughter Botox bonding experience that had resulted in temporary simulacrums of rejuvenation here and there on her face. She was trying to recall some funny remark of Nina’s on the subject of needles when Kev said, ‘Loretta?’

‘Right,’ said Mrs Plansky. She sipped from her water bottle and took in the here and now. They had an audience, maybe fifty or sixty members of both clubs, sitting in lawn chairs and on the clubhouse patio, some fanning themselves. It was the first hot and humid day of the year. Mrs Plansky was unsure of Kev’s age but probably no more than five or six years less than hers, and she herself was seventy-one. She had an artificial hip, in no way detrimental, and in fact the best joint in her body, a sturdy body that had served her well in many ways, even capable of some foot speed at one time. She’d been a tomboy as a kid, played PeeWee hockey with the boys back home in Rhode Island. But actually irrelevant to the present situation, the headline for which would be: trailing 6–1, 5–love in a best-of-three set match. She didn’t have to look to know that some of the spectators were glancing at their watches, planning drinks, dinner, perhaps a quick sail or swim. That was the overview. Mrs Plansky, going back to her days in business, believed in overviews. Norm had been more about winging it; a bit strange since he’d been the one with the engineering degree.

She put her hand on Kev’s shoulder, a thick shoulder, much more muscular than Norm’s, Norm being husband, business partner, tennis partner, and love of her life, with whom she’d played countless matches and had looked forward to many more when they retired down to Ponte d’Oro, but one of those quick and merciless cancers had felled him soon after. How she’d loved playing with him! But Kev was the better player. The thought gave her a pang of disloyalty. Was this the time for all that? Certainly not! Overviews yes, but you could overdo the over part and end up with a blurry picture. Focus, Loretta!

‘Kev,’ she said. ‘You’re wrong about running out of time.’

‘Oh?’ he said, an expectant expression crossing his face. For a second or two she could see how he’d looked as a kid.

‘There is no clock in tennis. Let’s stretch it out, way, way out.’

Kev laughed. ‘Like Einstein’s relativity!’

‘I don’t know about that,’ said Mrs Plansky.

And they were both laughing when they took their places on the court to return serve. Puzzled frowns appeared on the faces of their opponents. Who laughs when they’re getting their asses kicked?

Late afternoons in April could bring enormous thunderheads looming in off the sea, and somehow those four players – Russell Curtis, Jenna St. Something or Other, Kev, and Mrs Plansky – were still on Court #1 to see those thunderheads closing in. By that time Mrs Plansky knew that Russell was the first name, since Jenna had taken to hissing to him after some of the points, as in ‘Russell! Hit to the open court!’ And ‘Russell! He’s getting you with that wide serve every goddam time!’ Also, ‘Her backhand volley, Russell? Hello? How many times do you need to see it?’

Mrs Plansky and Kev chipped and sliced, lobbed and dinked, came to the net, stayed back, served Australian, used signals, pretended to use signals, went down the middle over and over until Russell and Jenna were squeezing in so close that they whacked each other’s rackets trying to make the shot, which Mrs Plansky and Kev took as an invitation to start hitting down the line. Time expanded beautifully. Mrs Plansky stopped feeling flushed, her flush perhaps finding its way to Jenna’s face. Mrs Plansky’s kick serve even appeared, after an absence of fifteen years. Not a word was spoken, not between Mrs Plansky and Kev. There was no need. Had she actually patted him on the butt as he pulled off yet one more killer backpedaling overhead? Good grief.

Final score: New Sunshine 1–6, 7–6 (11), 6–4. They’d hugged at the end, pretty standard in mixed doubles. Kev had lifted her right off the ground – which was not standard – somehow making it look easy. She’d been struck by a strange and simple thought at that moment: More.

The first raindrops were falling by the time Mrs Plansky and Kev left the clubhouse. He’d come on his bike, so they stowed it in the back of her SUV – Mrs Plansky, a mother and grandmother, drove SUVs by long habit – and she took him home, their two trophies bumping together in the backseat.

‘Wow,’ Kev said. ‘Unreal.’

Mrs Plansky nodded. She tried to think of any other time in her life when the unreal had really happened, and found several right away. For example, there was the camping trip when the kids, Nina and Jack, were small, Norm working at a small engineering firm and making little, Mrs Plansky a paralegal and making slightly more, when she, fixing sandwiches, said, ‘Wouldn’t it be nice if the knife could toast the bread while you sliced?’ An unreality that just popped out. Norm, dozing in his sleeping bag, sat right up. Three years later came the Plansky Toaster Knife, and the small fortune – quite small given the kinds of fortunes that are out there these days – that followed. Or how about Norm on his deathbed – Norm, who couldn’t hold the simplest tune – suddenly singing ‘My Funny Valentine’ in a smooth, lovely baritone? And he a tenor to boot? Or take that fairly recent Romanian adventure where after decades of law abidance, she’d purloined—

‘Next left,’ Kev said, gesturing toward a lane lined with silver buttonwoods and paved with sun-bleached seashells. His hand touched down on Mrs Plansky’s hand, resting on the console. He gave a little squeeze. Her hand, acting strictly on its own, rolled over and squeezed back. Rolled over? Rolled over like… like some… some eager beaver rolling over in bed! Eager beaver? For God’s sake! Get a grip. The flush, maybe just on loan to Jenna, returned to her face. What with endorphins and all that, Mrs Plansky knew she was in a heightened state, just from the length of the match, never mind the triumphant conclusion, but still. Was something about to happen? If so, what? Despite the fact that she was not dating – although she and Kev had had dinner together at the new sushi place by the marina once or twice, which couldn’t be called dating – and had never visited any of those apps – Match.com, OkCupid, Mishmash.net, whatever all those names were – and was perfectly content with things as they were, deep down Mrs Plansky knew the answer to what could happen. It could be… anything! Somewhere in the middle distance thunder boomed.

Kev’s hand moved away. He pointed. ‘Second driveway.’

Ah, a baritone. She hadn’t realized that until this moment. A full-time baritone. The rain was pelting down now, the windshield wipers on max, the car steaming up inside. Steaming up would be an example of that literary technique where nature imitates the moods of man, the word not coming to her at the moment, although she could picture Mr Cabral, tenth-grade English teacher, a little guy with nicotine fingers and nicotine mustache, explaining the whole thing. Mrs Plansky took the second driveway. Thunder boomed again, closer now, and the sky tried out a rapid color selection, settling on purple.

Kev’s house rose at the end of the driveway, an elevated house with hurricane-resistant curved lines, streamlined and perhaps bigger than it appeared. Through the gun barrel pilings she could see the ocean, a strip of beach, a white, crimson trimmed boat with a tall tuna tower, tied to a wooden dock. Perhaps yacht would be the right word, more precise than boat. How big? Mrs Plansky was no expert on yachts – Norm prone to seasickness in anything bigger than a kayak – but she guessed about fifty feet, although the yacht, streamlined like the house, also might be bigger than it appeared.

Mrs Plansky parked in front of the house. ‘My, my,’ she said, ‘what a lovely—’

Time, which had slowed down so nicely on Court #1 now sped up in a way that made it hard to keep track of things and was not nice at all. First came another boom, this one the loudest yet, practically right on top of them. Then – but more accurately at the same instant – the sleek white yacht with the crimson trim burst into flames, exploded, was replaced by a ball of fire.

Kev jumped out of the car and ran under the house, toward the dock. Mrs Plansky jumped out, too, and ran after him through the pouring rain, for no reason, just instinctive heart-pounding thoughtlessness on her part, her mind completely empty of thought. Well, not quite true. There was one thought: What about the lightning that always preceded thunder, thunder actually being the sound of lightning, as Norm had explained to the kids on another one of those camping trips? Mrs Plansky had seen no lightning.

2

Too late. There was nothing to be done, the fire already in its roaring midlife stage. Mrs Plansky realized all that but at the same time she found a hose coiled on the dock, turned on the faucet, and was now sending a limp stream of water into the conflagration, somehow all the more pitiful since it was still raining pretty hard to no effect on the fire. From where she stood she could see the name of the boat, gold-painted on the stern: Lizette. The name melted away, slowly at first and then fast. The lines tying the boat burned up and Lizette tilted toward the sea and began drifting off. Roaring amped down. Sizzling amped up. Mrs Plansky glanced at Kev. He stood by a mooring bollard, arms folded across his chest, face impassive, the fire reflected in his eyes. Mrs Plansky turned off the faucet, recoiled the hose, and moved beside him, putting her arm around his back. They were both soaked through and through.

At first he didn’t seem to notice her, might as well have been a statue with a pulse. She thought about saying, It could have been worse, but that was stupid. What would be helpful or comforting or at least relevant that wasn’t stupid? She still hadn’t come up with anything when the rain stopped all at once. Kev suddenly came to life, turned, took her in his arms, and kissed her, a kiss that grew deep, passionate, intimate, and took Mrs Plansky completely by surprise, but which she returned in kind. Surprise number two, although in kind might not have been accurate, since she’d been out of practice with Norm gone – as long as you didn’t count the events of one unplanned night during her Romanian adventure, a sort of sub-adventure. But now the memory of that got mixed in with present-time action, a super-charging combo of mind and body, so who knows what would have come next there on Kev’s dock, with Lizette, her fire flickering out, now mostly underwater, only the sport tower and the ends of the outrigger rods still showing? Mrs Plansky’s heightened state had heightened some more, so much that she felt like a different person and not a seventy-one-year-old widow with an artificial hip and perhaps – well, no perhaps about it – a few extra pounds on board a body that had always been strongly built, which was how she preferred to look at that whole question. So the truth was that anything could have come next out on Kev’s dock despite – or because of! – the end of Lizette, but right then sirens sounded, close by and urgent. They let go and backed away from each other. Thunder boomed one more time, distant now and in the west, the storm drifting inland.

A fire truck rolled up the driveway, lights flashing, siren off, seashells crunching under the big wheels. Three firefighters hopped out and hurried toward the dock, two men and a woman. They had numbers on their helmets – 27, 99, 133. They took in the remains of the fire and didn’t bother unspooling their fire hose. 99 snapped a few photos on his phone and 133 made a call on his. 27, the woman, turned to Kev and Mrs Plansky, gave them each a quick close look.

‘Anyone on board?’

‘No, thank God,’ Kev said.

‘This your place?’

‘Yes. Well, mine. My name’s Dinardo.’

27 motioned toward what remained of Lizette. ‘What happened, Mr Dinardo?’

‘We were just driving in and the rain was coming down hard but I got a pretty good look. It was a lightning strike. Toward the stern, I think, but I’m not sure. It was just a big bright flash.’

27 glanced at Mrs Plansky. ‘Anything to add to that?’

Mrs Plansky didn’t quite know what to add. She would have preferred subtraction, specifically regarding the lightning strike. There had to have been one but that wasn’t the same as seeing it. She ended up saying, ‘I don’t think I’ve ever heard a louder boom.’ And thus sounding stupid.

27 didn’t seem at all surprised by that. She turned back to Kev.

‘What kind of vessel?’

‘Bertram Fifty-S.’

‘Diesel?’ she said.

‘Yes.’

‘Tank capacity?’

‘Twelve hundred and some.’

‘How full?’

‘Only about a quarter, maybe less.’

27 turned to the other two firefighters, standing on the edge of the dock. ‘Any slick on the water?’

‘Nope,’ said 99, a short, broadly built guy with a grizzled beard.

‘Musta all combusted,’ said 133, a tall, skinny kid who looked like he might still have been in high school.

‘Uh-huh,’ said 27, her tone discouraging further comment on his part. The kid looked down at his shoes – not shoes, of course, but heavy rubber boots with yellow toe caps. ‘And get hold of the harbormaster.’

‘Already done,’ said 99.

27 turned to Kev. ‘How’s your insurance?’

‘Good,’ said Kev.

‘Don’t want to jump the gun but the harbormaster will be wanting to short haul what’s left down there.’

‘Should be covered,’ Kev said.

27 nodded. ‘Act of God.’

‘Yeah,’ said Kev. He shot Mrs Plansky a quick glance.

‘How about we get started on the paperwork?’ 27 said.

‘Sure.’ Kev gave Mrs Plansky a little smile and followed 27 to the fire truck.

The sky began to darken, night moving in fast the way it did down here, down here being how Mrs Plansky still thought of Florida. A bright light appeared to the south, grew brighter very fast, and soon the harbormaster’s patrol boat was gliding into the dock. 133 helped the harbormaster tie up. 99, the short, thickly built guy with the grizzled beard, approached her.

‘Mrs Plansky?’ he said.

‘Uh, yes?’

‘Thought I recognized you.’

That was the moment Mrs Plansky realized she was still wearing her sleeveless peach-colored tennis dress with white trim, not at all a water-repellent garment and still soaked from the rain and therefore on the clingy side. Very clingy, in fact. She could feel just how clingy it was, especially here and there, but dared not look.

‘Ah,’ she said, ‘I’m sorry but I don’t—’

‘No, we never met but I’ve seen you a few times.’

‘Oh?’

‘From out in your parking lot. Picking up Lucrecia when her car was in the shop. I’m her worser half, Joe Santiago.’

‘Of course, of course.’ Although she would have preferred to somehow arrange her arms in a body shield position, she shook hands with Joe Santiago. ‘I don’t know what we’d do without Lucrecia.’

‘Same,’ said Joe.

Lucrecia was the home health aide who came to Mrs Plansky’s place for four hours every weekday to… well, to basically entertain Mrs Plansky’s dad – who despite being ninety-eight had no apparent health problems, although he himself in toto was just about unfailingly problematic – and Mrs Plansky regretted her last remark immediately. Did it sound patronizing? What could she say to smooth things over? Nothing came to her. Then something sizzled out on the water, actually more of a hiss. They both turned to look but there was nothing to see except dying embers. Lizette was gone.

‘We were just playing tennis,’ she said.

Joe sounded very surprised. ‘You and Lucrecia?’

‘No, no, although I’m sure it—’ Mrs Plansky slammed on the brakes before she began a description of the fun she and Lucrecia would have on the tennis court, both she and Joe knowing full well that Lucrecia had no interest in tennis or any other sport. She gestured toward the fire engine, where Kev was saying something and 27 was writing it down on a notepad. ‘With Kev. Mr Dinardo. He lives here.’

Joe glanced around. ‘Where’s the court?’

‘Not here, but earlier, over at—’

Before she could make herself even more ridiculous, the man at the wheel of the patrol boat called over. ‘Joe? Got a sec?’

‘Nice seein’ ya,’ said Joe, walking away.

Mrs Plansky wanted to call after him: I’m not even rich! Just comfortable! In her mind she heard what that would sound like before she could speak.

She stood alone on the dock, watched the harbormaster’s crew shine flashlights on the water. Somewhere farther off a piece of wreckage burst into flame. She watched it die down to nothing. Did people still use the word comfortable to mean whatever the hell she meant by it? Probably not. Your language gets outdated as you age. You end up becoming like a foreigner. My goodness! What thoughts were these? She heard Norm’s voice in her head. Hook.Just the one word, his customary signal that it was time for them to leave wherever they were, the hook being the kind that whisked vaudeville performers offstage.

Mrs Plansky walked off the dock, slowing down when she reached the fire engine. Kev interrupted whatever 27 was telling him and turned to her. ‘Sorry for all this, Loretta.’

‘I just hope everything’s okay,’ she said.

‘Should take a few days to sort out. I’ll be in touch.’

‘When you have time,’ said Mrs Plansky. In her mind – and so brazen! – she thought but absolutely did not say, To be continued. Instead she waved what she imagined was a noncommittal goodbye, then got into her car and drove away. The fire engine lights kept flashing in all her mirrors until she made the turn onto the coast road. She dialed up the heat, hoping it would dry out her tennis dress but it only made things clammy. First thing when she got home would be a shower.

As she passed the Green Turtle Club, a Bahamian-style bar with conch fritters Mrs Plansky craved now and then, she hit a little pothole and the trophies bumped together in the backseat. What remained of her heightened state lowered itself back down to ground zero. Mrs Plansky’s eyesight was kind of marvelous since the cataract surgery, a tiny personal miracle. But she hadn’t seen the lightning strike. She probably didn’t see a lot of things.

Sometimes Mrs Plansky pictured abstractions in her mind. She’d been doing it since childhood, had never really thought about it, or wondered if others did the same. For example, she now pictured a door, just a plain simple wooden door, like you’d find in millions of homes. She closed it on the lightning question.

After Norm’s death, Mrs Plansky sold their nice little house on the inland waterway – certainly little compared to the other houses around – and bought a condo on a rise overlooking Little Pine Lake, not far away. Rises were rare in the county and the Little Pine condos, all twelve units, took advantage of the slope, facing away from the entrance and overlooking the lake, a perfectly round spring-fed lake that was refreshing year round, although no one had been swimming in it lately. Mrs Plansky’s condo was number 12, an end unit. She parked and went inside.

Lucrecia was in the front hall, dusting the top surfaces of the picture frames. She didn’t have to do that. Cleaning wasn’t part of the job but bringing that up was pointless. Lucrecia liked to keep busy. She was in her late fifties, looked something like Carmen Miranda, minus the glamour part, but somehow just as impressive or maybe more, at least in Mrs Plansky’s eyes.

‘Lucrecia? You’re still here?’

Lucrecia was not one to respond to questions in a traditional manner, if at all. ‘Oh my God! You look like a drowned rat. Joe just told me all about it. What a scare!’ From out of nowhere she produced a towel and tossed it to Mrs Plansky. ‘But at least you won. Felicidades.’

‘Thanks.’

‘Where’s the trophy?’

‘Left it in the car.’

Lucrecia laughed. ‘What a cool customer!’ she said. ‘Dry your hair.’

Mrs Plansky, the uncoolest customer Mrs Plansky knew, dried her hair. ‘How’s he doing?’

‘Just fine. Had a nice dinner – spaghetti with that meat sauce he likes, with the anchovies, plus they shared a bottle of red wine – and went to bed.’

‘They?’

Lucrecia nodded. ‘She claimed to be suddenly tired. They both claimed to be suddenly tired.’

Mrs Plansky glanced past Lucrecia. The condo had two bedrooms: Mrs Plansky’s on the first floor and a guest room upstairs. There’d also been a small first floor study, but it had been converted into a bedroom for her father when… when how to put it? When he got thrown out of Arcadia Gardens? Close enough. Arcadia Gardens was an assisted-living place about forty-five minutes away, where her dad had passed two or three somewhat disruptive and expensive years, the expense borne willingly by Mrs Plansky and the disruptiveness just borne. He’d had many disagreements with fellow residents and staff, although none violent – with the exception of the beer bottle incident – but the climax, as it were, had come, as it were, on account of his romantic life, of which Mrs Plansky had been unaware for a long time and was now way too aware. It turned out he’d had a girlfriend, as he put it, or two in Arcadia Gardens, but on different floors and supposedly ignorant of each other’s existence. Both were named Polly, a setup for trouble, but in the end trouble had come from somewhere else, much closer to home. One of the Pollys was just a few years younger than Mrs Plansky’s dad, but the other was still in her seventies, meaning not much older than Mrs Plansky. She’d squirmed, an actual physical squirm, when she first heard that. There was some disagreement among the staff whether the Pollys knew what was going on, or if they even cared. When it was all over Mrs Plansky had asked her dad about that. ‘I wouldn’t know,’ he told her. None of that mattered. What blew things up was the appearance of Clara Dominguez de Soto y Camondo, Lucrecia’s mother. She’d met Mrs Plansky’s dad when he was staying here at the condo, with Lucrecia hired to watch over him while Mrs Plansky was in Romania, Arcadia Gardens being closed to him on account of Mrs Plansky’s money difficulties at the time, which turned out to be temporary. Not that she’d made a complete financial recovery but she had more than enough. Those with more than enough, in her opinion, should keep their traps shut about… well, practically everything. The point was that the recovery had made it possible for him to return to Arcadia Gardens, reluctantly, and as it had turned out also briefly.

Like a college kid from the fifties – which was what Mrs Plansky’s dad had been, Princeton as he mentioned at every opportunity and even non-opportunity, although people seemed to care about that less and less – smuggling a date back to his dorm room, he’d snuck Clara into Arcadia Gardens on a few or possibly more than a few nights. Clara was her dad’s age or even older. That was what finally incensed the Pollys, first the younger and then the older, or possibly the reverse. Things had gotten noisy late one night, first in her dad’s room but then spilling out and involving a lot of spectators and kibitzers on several floors. The next day Mrs Plansky and her dad checked out other assisted livings within a hundred-mile radius. That night he was back at Little Pine Lake.

‘Hungry?’ Lucrecia said. ‘I can fix you something.’

‘Thanks,’ said Mrs Plansky. ‘I’m fine.’

‘Want me to wake her up, take her home?’

Mrs Plansky shook her head. ‘She’s no trouble.’

‘We both know that’s a crock,’ said Lucrecia. ‘I’ll swing by first thing.’

After Lucrecia left, Mrs Plansky took her shower. To get to the master suite she had to pass the former study, now her dad’s bedroom, on the way. She slowed down when she came to his closed door. She heard Clara saying something. Although Clara had come penniless from Cuba at the age of nineteen, where she’d been something of a figure on whatever they called their debutante scene, she still didn’tseem to speak any English at all. Her dad knew only a few words of Spanish, such as toro, which he’d picked up on a long-ago trip to Seville with a cigar club he’d belonged to, and con hielo, which he used when ordering his Scotch from any olive-skinned bartender. Nevertheless Mrs Plansky was pretty sure she heard him chuckle at whatever Clara had just said. A low chuckle, but somehow weighty, as though powered by the lungs of a much younger man. Perhaps there was a much younger man in there, and things were even more off the rails than she thought.

3

Mrs Plansky awoke to find herself in her favorite sleeping position, a sort of twisted K. Norm – an engineer, don’t forget – had come up with an inverted C that fit the twisted K perfectly. Once, at a boring party, or maybe even at a not-so-boring one, she’d turned to him and said, ‘How about some of that old KC?’ Perhaps raising her voice a bit over the din. Some nearby guest overheard and jumped in. ‘Can’t beat the barbeque,’ she’d said. But Norm got the message and they’d skedaddled soon after. Wouldn’t a little skedaddling now be just the—

She sat up. The light coming through the curtains wasn’t right. Well, it was right, but just for later. Had she slept in? Mrs Plansky awoke naturally between 6:45 and 7 every single morning. She checked the bedside clock: 8:20. 8:20? Good grief. The day was practically wasted already. Wasting time was a sin in Miss Terrance’s book, Miss Terrance having been her ninth-grade home ec teacher, back in a time when there was such a thing as home ec. ‘God gives us a certain amount of time, girls. Wasting any of that gift is an insult to him.’ Classroom instruction from another time – and a time Mrs Plansky was unwilling to say was better than the present – but it still lived inside her as part of her ramshackle philosophy of life. So get up now! That was the point.

Mrs Plansky got out of bed. There was some bodily resistance, especially from her new hip, the left one. Not a brand-new hip – now in its second year – but it was a big success, had been quiet for months. Of course she’d been on the court yesterday for what must have been almost three hours, so what did she expect? After all… At that moment she remembered what had happened at Kev’s: storm, explosion, fire. She checked her phone. A bunch of congratulatory texts from New Sunshine members, but nothing from Kev. She gave her head a smack – very light, mostly symbolic – to encourage it to remember faster in future. Then she put on her robe, steadied herself by the dresser, moved her left leg this way and that. Good enough.

Mrs Plansky went down the hall. The door to the former study – she wasn’t ready to call it her dad’s room just yet, preferred to think in terms of a visit with no fixed end date – was open, no one inside, and the bed was made, which was a first since he’d arrived. Not that he didn’t care whether his bed was made. He cared very much and had specific and detailed beliefs on proper bed making, which he was happy to share with any actual bedmaker.

Mrs Plansky found her dad on the patio, a nice patio, private and overlooking the lake, where a brown pelican was rising heavily off the water, a squirming crab in its long yellow beak, a beak with a strange red mark near the tip. Her dad was taking no notice of that, instead was sitting at the round glass table, his wheelchair nearby, and polishing off a fine-looking breakfast of bacon and eggs over easy but not too easy, which was how he liked them. Therefore, since neither he nor Clara could cook anything, Lucrecia had already been by.

‘Morning, Dad.’

He didn’t look at her but he did wave a fork in her direction. ‘Take a seat.’

And just like that, she was a guest in her own home. ‘Don’t mind if I do,’ she said, sending a message he showed no sign of receiving. He dipped a strip of bacon in a marmalade jar and chewed on it slowly. Her dad had once been handsome in a Mad Men way but there wasn’t much of that left, and from certain angles he even looked a little orc-like, although he did have an almost full head of hair, and not all of it white. He was wearing pressed khakis with a golf-themed belt, polished tassel loafers, and a pajama top.

‘Pour me some coffee?’ he said. ‘There’s a princess. And have some yourself.’

Lucrecia had left the Thermos-style carafe on the table, plus an extra mug. Mrs Plansky poured and sat down, not opposite her dad but sideways to him, partly so she could enjoy the view, but also so she could keep an eye out for Fairbanks. Like many gators in the ponds, lakes, springs, and backwaters of Florida, Fairbanks had been given a harmless-sounding name by the locals, in his – or possibly her – case by Ms Pietsch of condo #9, a retired professor of film history who’d been the first to encounter Fairbanks on a morning kayak paddle some months before and sold out soon after.

‘Too bad I hadn’t known about that,’ her dad said, still at Arcadia Gardens at the time. ‘Woulda snapped it up.’

With what money? Mrs Plansky hadn’t said at the time.

Chandler Wills Banning – Mrs Plansky’s dad – came from a family that, as Mrs Plansky now understood in retrospect, had been on a descending glide path for a long time, but he was the one who tipped the nose straight down, buying for real into a personal financial image he had to have known, if he simply checked the numbers, was false. First he’d wasted his inheritance, then had a career in various corners of the finance industry where he had to compete against people who’d gotten there by competing, which – again she understood in retrospect – he had no idea how to do. In some ways, maybe all, he was the exact opposite of Norm. Once – this was after it was clear that the Plansky Toaster Knife was a big success, although not crazy big, Mrs Plansky never under any illusions about that, and around the time her dad requested that first ‘eeny weeny super short term’ loan – she’d said to Norm, ‘Did he misread the scorecard? Thinking it says he was born on third base when it was actually first?’ How Norm had laughed at that! Just delighted. He’d kissed her on the forehead and told her she was the best. To have someone in your life who was delighted by you: who was luckier than she was? Norm himself had never said one bad word about her dad. Neither had Mrs Plansky’s mom, who’d died at forty-nine of breast cancer when Mrs Plansky and Norm were just starting out, long before thetoaster knife. On her deathbed she’d said to Mrs Plansky, ‘I just don’t understand.’ Which Mrs Plansky at the time had assumed was a reference to dying so young, and not her husband.

‘What kind of coffee is this?’ her dad said.

‘Same as always,’ Mrs Plansky told him. ‘The dark roast from Panamanian Moon.’

‘It tastes different.’

Mrs Plansky had no comment on that. She waited for him to make sure she understood he meant different in a bad way, but that wasn’t the direction he took.

‘We need a TV out here.’

‘We’ve discussed that, Dad.’

‘Not when I was around. The TVs are better now. Ever heard of pixels? The picture’s great outside.’

‘I like having TVs inside,’ said Mrs Plansky.

He gestured at her with a butter knife. ‘What if there’s something good on when you’re outside?’

‘Like what?’ That was unfair and Mrs Plansky regretted it at once. He had no defense to a comeback like that. Why was she crabby today? Crabbiness was intolerable, meaning in herself. She could tolerate it in others, within limits.

But now he surprised her. ‘Like a space shot,’ he said. ‘When they walk on the moon.’

Mrs Plansky laughed. She reached out and patted his hand. ‘Next time they walk on the moon we’ll have a TV out here, I promise.’

Her dad laughed, too. Maybe a little too long and edging into crazy, but it was nice to hear. She was wondering whether her mention of the coffee shop name was somehow twisted into all of this when he dabbed his chin – and then his forehead – with his napkin and said, ‘Had a nice powwow with Jack yesterday.’

‘With Jack?’

‘A confab. Or maybe the day before.’

‘You called him?’

‘Nope. He calls me.’

‘He does?’ Mrs Plansky tried to remember the last time Jack had called her. Last Christmas? No, she’d called him, actually waking him up even though it was noon, Arizona time. ‘How often?’ she said.

Her dad shrugged. ‘That’s the trouble these days. All this…’

‘This what?’

His forehead, already furrowed plenty, furrowed more, deep Vs of annoyance. ‘You know.’

She took a guess. ‘Quantification?’

‘So why’d you ask in the first place?’ He buttered a slice of toast, then turned it over and buttered the other side.

‘What do you talk about?’

‘Huh?’

‘You and Jack. When he calls you.’

‘He’s my grandson.’

‘I know that, Dad.’

‘Also there’s Nina, my granddaughter. Did she end up marrying that asshole?’

Which asshole are you referring to? That was what some devil in Mrs Plansky wanted to say. She went with, ‘Who do you mean?’

‘That guy, Matt, Matthew, whatever the hell.’

‘They broke up.’

‘Any reason?’

A perfect question that seemed to show a brutal but defensible understanding of Nina, but did he mean it that way or was it just some by-product of what was going on in his brain these days, all the firings and misfirings? Mrs Plansky sipped her coffee. Was he right about that, too? It did taste different, less… well, just somehow less. She’d been surprised by the breakup of Nina and Matthew, as Nina liked to call him, or Matt as it seemed he preferred to be called. Mrs Plansky had heard several explanations for the breakup and didn’t know what to believe. She did know that Nina was the marrying type. First had come Zach, father of Emma, Mrs Plansky’s granddaughter, now on a semester abroad. Next in line was Ted, father of Will, her grandson, possibly back in college in Colorado, and if not then a ski tech at Crested Butte, or maybe a chairlift attendant. Then there’d been a second Ted, called Teddy, unless the first Ted had been Teddy. Mrs Plansky would not have bet money on the answer to that, not a surprise because she’d never in her life bet money on anything.

‘Well?’ said her dad.

‘Well what?’

‘I’m waiting for an answer.’

For a troubling moment Mrs Plansky couldn’t remember the question. She even considered asking her dad to repeat it. What if he could? That would be worse! But oh, what a nasty, selfish thought! She banished it immediately and as it left the tiny realm of her mind, the question – any reason? – popped up its place.

‘I guess Matthew wasn’t the marrying type,’ she said.

‘Who is?’ said her dad. Then all at once he grew agitated. He shook his finger at her. ‘I never cheated on your mother while she was alive. Not once! Well, maybe once.’ He began to deflate. ‘And that wasn’t even…’

He left that, whatever the hell it was, hanging. Mrs Plansky drank more coffee and ignored him. Pointedly? Possibly, but she did nothing to moderate that.

He picked up another bacon strip, dipped it in the marmalade jar, and paused. ‘Had a nice talk with Jack,’ he said.

‘You were going to tell me what it was about.’

‘Business.’ Her dad made a dismissive gesture with the bacon, like business wouldn’t interest her, or perhaps would be over her head. Mrs Plansky had helped build a successful company in a highly competitive space from nothing. She’d been in charge of sales and marketing, done all the hiring and firing, handled the banking relationships. What was there to say?

‘In what context?’ Mrs Plansky settled on that, mastered any temptation to be infuriated, disdainful, or even amused. She had been, after all – and maybe still was, except for the lack of an actual paying job – a businesswoman, and had talked more productive business than he’d dreamed – She shut her mental trap.

‘Picking my brain, mostly,’ her dad said, or something like that. He seemed to be chewing on the whole bacon strip at the same time, a little marmalade blob oozing from the side of his mouth. ‘Jack values my opinion on various…’ He thought for some time and added, ‘… aspects.’

‘Aspects of what?’

‘Business. For example, business opportunities.’

‘Jack’s looking for a job?’

‘Wouldn’t say that. More in the line of business opportunities. Happy to help. I know something about the subject, of course, stands to reason.’

‘I thought he was happy at that place.’

‘Place?’

‘The tennis center in Scottsdale. The membership is huge and hasn’t he been helping out with the ASU program?’ Dark thoughts stirred in Mrs Plansky, threatening to make inroads into her consciousness. Dark thoughts about her son – like, maybe the ASU thing was actually a suggestion of hers, a suggestion Jack might never have followed up on; like, maybe she had no actual data on the membership numbers at the tennis center in Scottsdale; like, maybe Jack’s previous gig, also in Scottsdale, had been a lot better, but he’d left to pursue some sort of start-up that had soon dead-ended; like, maybe Jack saw himself as a failure, making it even worse than his simply not loving what he did. That was excruciating to her, not because it made her a failure, too, at least partially, which was true, but because she loved him so much he was part of her soul. But last time she’d seen him – two Thanksgivings ago – there’d been failure-knowledge lurking in his eyes, which she realized only now in retrospect. A two-year time lag? Was there a slow-on-the-uptake competition? She had the goods.

‘What’s ASU?’ her dad said.

‘Arizona State.’

‘Never heard of it. And didn’t he graduate from college already? I thought Will was the one who…’ His voice trailed off. His tongue emerged, found the marmalade blob, reeled it in. ‘Broaden your thinking,’ he said.

‘Excuse me?’

‘You gotta broaden your thinking, Loretta. Jack sees what’s out there. Wants to be a part. Why don’t you get that?’

Mrs Plansky got that. The year before, Jack had fallen in with a couple of entrepreneurs from Mesa – their names not coming to her – who wanted to partner with him in opening a chain of cold storage facilities coast-to-coast. Through Jack – ah, yes, the last time he’d called her, now filling its box in her disordered mental spreadsheet – they’d invited Mrs Plansky to be a supporter to the tune of $750K, which she hadn’t had the time to decline gracefully before they were indicted on a number of federal charges, luckily regarding an earlier scheme that hadn’t involved Jack.

‘Tennis is just a game,’ her dad said. ‘A fine game.’ He gave her a big smile. Somehow he still had all his original teeth and they weren’t even particularly yellow. ‘And I know you were always good at games. For God’s sake! That’s what I liked about you! But Jack’s a man, after all. He’s looking for bigger things.’

All at once, Mrs Plansky wanted to laugh. She felt an enormous laugh building inside her, just bursting to burst out, her natural self saving her from potential hurt, at least as far as she knew. But her dad wasn’t done.

‘He was thanking me for putting him in touch with that guy,’ he said.

‘What guy?’

‘You know.’

‘I don’t.’

‘Yeah you do. That tennis partner of yours.’

‘Kev Dinardo?’

‘Sure about that? I thought it was Dev.’

4

‘Dad?’ Mrs Plansky said. ‘How do you know him?’

‘Who are we talking about?’ said her dad.

‘Kev Dinardo.’ Kev had never been to the condo and how could her dad have met him out in the world?

Her dad gazed out at the lake, the surface unruffled as it often was in the morning. ‘Who says I know him?’

The ruffled one was her. She forced her voice not to show it. ‘You must,’ she said, ‘if you recommended him to Jack.’

He thought for a while. ‘I’m not buying it.’

‘Not buying what?’

He gestured at the lake. ‘All that crocodile business.’ His eyes lit up. ‘It’s a crock!’ He laughed and slapped his knee. ‘Get it?’

Mrs Plansky got it but she was not in a laughing mood. ‘It’s a gator not a croc.’

Now he turned to her and the look in his eyes grew crafty. ‘So I’m right. There is no croc.’

She toyed with the idea of explaining that the Florida crocodile was rare and also not found this far north, that Fairbanks was a gator and had been spotted by a number of people, including she herself, but before she could launch into that – even though she knew it would be headed off some new unforeseen cliff – she was struck by a nasty revelation: her father had needed assisted living, in the broadest sense, his whole life. She shied away from that thought and ended up saying nothing.

Then came a long silence, broken only by the sounds of her dadenjoying his breakfast: buttering toast, stirring coffee, chewing bacon. Mrs Plansky watched the lake, willing Fairbanks to put in an appearance, but he did not. Finally her dad leaned back, dusting off his hands.

‘Kev?’ he said. ‘You sure about that?’

‘Yes, Dad.’

‘Not Dev?

‘No.’

‘Dev Dinardo sounds better. What’s that word?’

‘Alliteration. But it’s Kev.’

‘A mover and a shaker.’

‘Kev? He’s retired, Dad.’ She had Kev’s card somewhere, a very simple card with a sketch of a sailboat. There was also his phone number and one line of text: Retired from paying work, but nothing else.

‘There’s no retiring from success, as they say.’

Mrs Plansky had never heard that one. ‘What kind of success are you talking about?’

‘He made a lot of money.’ His tone turned angry, not over the top, maybe more like bitter. ‘What other kind is there? Of success, I mean. Try to keep up, Loretta. The point is I thought he’s the kind of guy Jack oughta know. I’m his grandfather. Hello?’

‘I’m his mother.’

‘Your point?’

What was her point, exactly? She couldn’t define it but plunged ahead anyway. ‘This success of Kev’s – what sector was it in?’

‘He hasn’t told you?’

‘We never discussed business. We’re tennis partners, Dad.’

‘Is he good?’

‘Very.’

‘Good as Jack?’

‘Nothing like Jack. Kev’s a fine senior club player. Jack was a touring pro.’

‘But he never made the big time.’

‘No.’

‘How come?’

How come? That was a question she and Norm had discussed many, many times, approaching it from all sorts of angles. Jack was strong, fast, just the right size at 6’2, 175 pounds, crushed the ball from both sides, served 120 with no seeming effort, had 20/15 vision in both eyes. In short, he looked like a top 100 player, but the highest he’d risen – to 319 – was nowhere in tennis, the curve at the top being so steep. Three hundred nineteen: why did she have to remember that number so well? But therefore, if the problem wasn’t physical didn’t it have to be mental or emotional? Perhaps rooted in his upbringing, and thus roping in Norm and Loretta? Not that they’d been pushy parents, their self-image wrapped up in the performance of their kid. They’d actually been more like Roger Federer’s parents – if stories about them were true: hands-off, encouraging Jack to play other sports, in all of which he excelled – he was a qualified scuba diving instructor, for example – not attending all of his matches, not close. Should they have taken the opposite approach, been parents of the intense type, even crazed? Mrs Plansky had made that argument a few times, one of those for sake of argument arguments, unreflective of her true beliefs. Norm loved when she got to the crazed part. He’d lean in and kiss her cheek and say, ‘How long could we have kept that up? Tennis players are like mathematicians. There are lots of great ones but only a few make a difference.’

‘The pyramid is very steep at the top,’ Mrs Plansky told her dad. ‘In almost anything else you can think of three nineteen would be fabulous.’

‘Huh?’

‘That’s why it’s so hard to make it on the tour.’

‘What tour?’

‘The tennis tour, Dad.’

‘Cry me a river,’ he said.

An annoying remark but she had no time to deal with it because all at once she had the answer to the riddle: Oh, Norm! Did we let him forget the most important thing – it’s supposed to be fun!

Silence.

‘Did you just say something?’ her dad said.

‘No.’

‘Like in a whisper?’

‘No.’ She leaned forward. ‘Do you know if Jack actually got in touch with Kev?’

‘Affirmative.’

‘Affirmative you know or affirmative he did?’

‘All of them.’

‘How do you know?’

‘I know a lot of things.’

She searched her mind for some sort of shortcut. ‘Good to hear,’ she said. ‘Among all those things do you know what Kev did or does for a living?’

‘Do I look like…’ He blinked a few times, slow blinks that were somehow more disturbing than fast ones. ‘A middleman?’ Ah, he’d been searching for a word. And found it. There was lots to admire about him. That was something to keep in mind. ‘So,’ he finished up, ‘why don’t you go to the horse’s mouth.’

‘Good idea.’

Mrs Plansky walked into the house, searched for her phone, which she thought was by her bed but turned out to be in the kitchen by the coffee machine, and called Kev. Straight to his voicemail, which was not accepting messages. Then she tried Jack, with the same result. She tried Jack again, hoping he’d seen that she called and would now pick up. He did not. She tried once more, just because.