Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

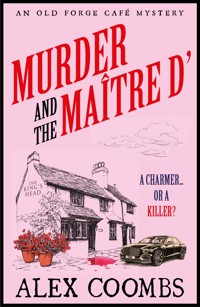

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: An Old Forge Café Mystery

- Sprache: Englisch

The Chilterns are at their best in May and The Old Forge Cafe is flourishing, which makes Charlie think about furniture that lives up to the standards her menu sets. Which is what persuades her to take on a job for a wealthy local businessman who suspects his daughter has fallen for a man who is not only a gold-digger but also a murderer. To Charlie's surprise, she knows him – he's the Maitre d' at the Michelin-starred restaurant at the other end of the village. Does his charm conceal a killer?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 379

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Also by Alex Coombs

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

About the Author

About the Publisher

Copyright

JOIN OUR COMMUNITY!

Sign up for all the latest crime and thriller news and get free books and exclusive offers.

BEDFORDSQUAREPUBLISHERS.CO.UK

Also by Alex Coombs

The Old Forge Café Mysteries

Death of a Mystery Guest

A Knife in the Back

Death in Nonna’s Kitchen

Murder on the Menu

The Hanlon PI Series

Silenced for Good

Missing for Good

Buried for Good

The DCI Hanlon Series

The Stolen Child

The Innocent Girl

The Missing Husband

The Silent Victims

MURDER AND THE MAÎTRE D’

ALEX COOMBS

To Mike W. Miss you every day, old friend.

Prologue

And you were there with Mummy, down by the lake. Of course, the locals didn’t call it a lake, they had their own word for it. You still remember it well that August, brilliantly blue, the white shapes of boats seen from afar on it. You recall the details, that’s not surprising, how could you ever forget? That summer’s day, she had been lovely to you at first, this was Nice Mummy. You knew that there were two of her, Nice Mummy and Nasty Mummy, in that pretty, oval face of hers with the soulful brown eyes. If only, you used to think, you could tell what was going on inside that head of hers, you wanted to be able to see what she was thinking, maybe change it. Maybe one day you would study how people think. Because now Nice Mummy had changed into Nasty Mummy. It was hard to know when it was going to happen, you had some ideas by now… she didn’t like other women around her, especially pretty ones. That brought out Nasty Mummy.

Right now there was no room for thought about these things. She was lying on the grass, her eyes open, unmoving, unblinking. A crow cawed and then the harsh sound stopped, disappearing into the blue sky with its decorative, puffy white clouds. The enormity of your act had stunned you, but the world didn’t seem to notice. The birds were fine, the earth revolved, the breeze blew and you looked at her lying there, motionless. And you smiled, you felt as if a rock had been lifted from your shoulders. She couldn’t hurt you anymore, that venomous tongue, her speech that was always alive to all your faults and none of your virtues, was now silent. Silent as the vanished crow.

You took a couple of breaths, tried and failed, for a tear to come, appearances are important. You looked at the lake far in the distance, the scene was unchanged. You realised then that despite the enormity of your act, the world still turned. You knew you would be unscathed by what you had done. Then you turned towards the big white house.

‘Dad, Dad…’ you shouted, ‘there’s been an accident.’

Chapter One

That gloriously sunny morning was May Day. I was prepping rhubarb in my kitchen and listening to Beech Tree FM, the local radio station, playing undemanding background music while I trimmed the stalks. It was a Wednesday, not usually a busy day of the week, and I was looking forward to a relatively relaxed lunch and dinner time service.

Gloria Gaynor was on the Golden Oldie Hour and I sang ‘I Will Survive’, along with her, a timeless classic musically, just like Steak Diane, Tournedos Rossini or Hollandaise sauce were classics of the kitchen. However, Gloria’s eternal feminine wisdom was wasted on my co-worker. Not that he objected to the message she conveyed, who wouldn’t have changed that stupid lock and thrown away the key? It was just the medium he didn’t like, that is pop music.

‘Can we turn this pish off please,’ he complained. Murdo, my Scottish sous, a metal fan, strongly disliked any other genre of music. Particularly pop music. Pop music of any description, and he wasn’t age discriminatory. Gloria Gaynor, Taylor Swift, baby-boomer pop like ABBA or Charli XCX, to his ears they were all equally unacceptable. Such is the cross I have to bear. But I was deeply fond of him and I uncomplainingly put up with the godawful racket he called music. Youngsters are famously intolerant, and Murdo was only twenty-one but with five years’ top quality kitchen experience behind him.

‘In a moment, Murdo,’ I promised, ‘after this song finishes.’

He muttered something inaudible and went on making the timbales for the vegetarian section of my menu. A timbale is a dish cooked in a mould. Mine had layers of aubergine and a filling of chopped sweated veg, herbs, capers and goat’s cheese. Then, once cooked through, they were inverted onto the plate and were served with hasselback potatoes and dressed curly endive. If you wanted, you could have them paired with a sous-vided chicken breast. It was a very popular dish.

‘That okay, Chef?’

I walked over to the prep table and glanced down at what he’d done. Twenty dariole moulds full to the brim; they looked good, I knew they would be. Murdo had a great pedigree, a Michelin-starred background from one of Edinburgh’s best restaurants. Not so shabby.

‘They are great, Murdo.’

The track we’d been listening to ended and then, what had previously been drowned out by the music and the din of the kitchen extractor fans became audible. Floating through the open door of the kitchen we could hear the distant sound of sirens. Murdo and I looked at each other questioningly and then I shrugged and we got back on with our respective jobs. So that’s how I was able to pin-point the time when I first heard the ambulance and the police cars that were the first signs that something terrible had happened, bookmarked in my memory between the rhubarb and the aubergine timbales.

Francis, my kp, looked up from scrubbing plates before stacking them in the large, Hobart dishwasher, his face red and sweaty through the steam, and wondered aloud. ‘Seems to be a bit of a thing going on in the woods, I saw three police cars there on my way over.’

‘Hope it’s the police cracking down on the fly-tippers,’ I grumbled. ‘The council have been promising to get tough for weeks now.’

‘Bet it’s not,’ Francis said, ‘they’re as much use as an ashtray on a motorbike.’

I was wrong about it being a quiet day. We only had a few bookings but we had a surprising number of walk-ins, and ended up having a ferociously busy lunch service and no time to think or speak until we started clearing down at half two. By then we’d forgotten about the police and the sirens, all external thoughts driven out by the volume of work.

Later I found out it wasn’t fly-tippers. It was something much more serious.

It was 3 o’clock and I was sitting in my now empty restaurant with Jess, my manager, relaxing over a pot of tea when there was a knock on my door. I looked up in surprise and saw a familiar face peering at me through the window. It was the police, in the form of DI Slattery.

‘Wonder what he wants?’ I muttered as I stood up to go and let him in. Jess caught my eye and grinned. She had a theory that the policeman had a thing for me.

Slattery and I had a somewhat complicated relationship. Initially, when I had first come to the village a couple of years ago now, he had been extremely hostile. He had suspected me of involvement in a sausage theft. That sounds like some kind of stupid joke; it wasn’t. The robbery had been from a local pig-farmer. Someone had broken into his refrigerated shed and stolen several thousand pounds’ worth of meat.

Then he had made me his lead suspect in a murder investigation, but since that terrible start, our relationship, initially so frosty, had thawed. Now we were friends. He lived just across the common from me, you could see his bedroom window 500 metres or so from mine. I knew he had a thing for me. I sometimes imagined him standing there late at night, forlornly looking out at the restaurant opposite and my lit bedroom windows, hoping.

He was a hard bastard, tough and uncompromising. I liked him a lot.

‘Hello, Charlie.’ His presence filled the room. He was six three, powerfully built and exuded an aura of command that made him seem even larger than he was. He looked like he wouldn’t need one of those sledgehammers that the police have to knock down doors, he could just run through it. He was also good-looking, if you like your men slightly rough around the edges. A kind of home counties Heathcliff. The trouble for DI Slattery though was that I wasn’t Cathy.

‘DI Slattery,’ I remarked. ‘Always a pleasure. Coffee?’

Slattery ran on coffee it seemed. Jess pulled a chair out for him and he sat down.

‘Please.’

I switched on the machine and ground the beans for his espresso. I looked at him expectantly, eyebrow raised, waiting for him to tell me why he was here.

‘Have you heard about what happened in Potter’s Wood earlier today?’ he asked.

I shook my head as I finished making the espresso and brought it over to him, sitting down opposite. ‘No, I’ve been in the kitchen all day, only just finished.’

‘I’m surprised no one noticed.’

‘Look, we were so busy we wouldn’t have noticed if World War Three had broken out,’ I said.

Jess frowned. ‘Is it anything serious?’

‘Very serious.’ He sighed. ‘It’s rather bad news, I’m afraid…’

Not the words you want to hear from anyone, least of all a policeman. I hoped it didn’t involve anyone that I knew. Slattery took a sip of coffee, nodded in approval and said quietly, ‘John Mayhew was attacked and killed there earlier this morning.’

I stared at him in disbelief. I thought of Mayhew, I could still picture everything about him with complete clarity. I was hardly overcome by grief. Memories of John, his unpleasant attitude, his rudeness, his shorty shorts, the stooped way he ran with his shoulders hunched up. I can remember thinking the wrinkly skin on his upper arms could do with a bloody good iron. And now, bastard or not, he was gone.

‘Well,’ Jess said, judiciously, ‘there’ll be a long list of suspects.’

Chapter Two

Jess had left; Slattery had told her he wanted to interview me alone and we sat opposite each other in the silent restaurant.

‘So what happened?’ I asked. I wondered if it was an argument that had got out of hand, John was a pugnacious kind of guy. Maybe he had confronted a fly-tipper, in which case he would have died a hero’s death, in my eyes at least.

‘How did…’ I didn’t like to say how did he die. That sounded morbid. I didn’t have to, Slattery guessed my question correctly.

‘He was shot with a crossbow bolt,’ he said, ‘at point-blank range by the looks of things.’ He shook his head wonderingly. ‘I mean, now I’ve seen everything. Not what I expected when I was called in. You don’t happen to know if he had any current enemies, do you, Charlie? You were in the same running group as him. Did you notice anything amiss, or did he happen to mention anything?’

‘I’m sorry,’ I replied, shaking my head. ‘Nothing in particular springs to mind. Look, this has been a bit of a shock. Give me some time and I’ll see if I can remember anything he said or anything else that might be of relevance.’

Slattery looked deep into my eyes, I think more because he liked the look of them than to see if I was lying. ‘I’d be grateful,’ he said, then he finished his coffee and stood up. ‘Thanks for the coffee, I’ll keep you in the loop. It kind of centres my thoughts talking to you Charlie.’

As I let him out I said, ‘I’ll keep my ears open.’

‘Thank you.’

I watched him walk away down the common heading for the wood and the crime scene. I shook my head and thought about how I had met John and where I should begin. I knew a lot more about him than I’d let on to Slattery, and not just him.

John had been involved with highly suspect people. One of them I knew was a potential killer. But now was not the time to tell Slattery that.

Begin at the beginning I suppose. On an April morning, three weeks previously.

My knowledge of John Mayhew was bookended by rhubarb. I had met him thanks to the maître d’ at the Michelin-starred place in the village, just round the corner from where I lived and worked in my restaurant. It had been the second week in April and with eerie synchronicity it had also been a Wednesday and I had also been prepping rhubarb in the kitchen.

I chopped the stalks into two cm sections and weighed what I had, about a kilo. I put them in a pan with 200 grams of sugar, five to one is the ratio I like to use. I went to the cupboard where I keep the herbs and spices. I was going to add a few star anise for a hint of background flavour, 100 ml of water and then on the stove.

I stared into the cupboard; it was far from bare but it didn’t have what I wanted. ‘Shit.’ I was annoyed. I organise my things in alphabetical order, the shelf I was looking at had a gap in between Smoked Paprika and Sumac. No Star Anise. I asked Murdo if he’d seen it. Shake of the head.

‘What’s it for anyway?’ Murdo asked, pointing at the pan. ‘That rhubarb compote?’

‘It’ll go with the panna cotta,’ I enthused. ‘They’ll look great standing in the middle of the rhubarb. They’ll be all white and wobbly and they’ll be surrounded by the pink of the compote, sprig of green mint on top for garnish, fantastic.’

‘Sounds good.’

‘It will be.’ And to make matters even better, it was local, seasonal, organic produce fresh from my friend Esther’s vegetable garden. It ticked all the boxes. Well, it would, if only I had the star anise. I didn’t want to drive to the shops, an hour out of my busy day. Then an idea came to me.

‘Hold the fort, Murdo, I’m going to go and borrow some off Strickland.’

‘Give him my regards.’

Upstairs, I pulled off my chef’s jacket, dragged a T-shirt over my head and left my restaurant, the Old Forge Café, and lightly jogged over the common to the other restaurant in the village, the imposing King’s Head, once a large country pub, now home to the Michelin-starred Graeme Strickland, the Napoleon of haute cuisine, as I liked to think of him. Mainly because he was short and a megalomaniac rather than Corsican or fond of tricorne hats.

I knocked on the front door and was let in by the maître d’, Tristan Smith.

‘Charlie!’ He looked delighted to see me. Tristan was a posh kid. Not outrageously so, just well-spoken and assured, good-looking in a public school kind of way, semi-glossy. He also had the floppy hair and the chinos and brogues to match. I thought of him as a kid, but he was about thirty and had done stints at a couple of Gordon Ramsay places. He was dark-haired, slightly taller than medium height, with a neat, dark beard and was generically handsome. He looked like a man in one of the catalogues that I get sent periodically for up-market outdoorsy leisurewear, normally accompanied by a leggy, slender wife with perfect teeth as they look delightedly in unison at some view or other. Tris was also very good at his job – you would have to be if Strickland employed you.

I’d eaten there a while ago. Strickland had owed me an apology and said it with food rather than flowers, which was a nice gesture. It was then I’d seen Tris in action, directing the service of the food and wine like a conductor of a small orchestra, not missing a beat and treading that fine line that lay between professional politeness and obsequiousness. He obviously had a way with the female clientele in particular, and I noticed that he had clearly memorised biographical details, asking after their children, jobs, husband, dogs, holiday with polished ease. I was impressed. He made people feel welcome but not in a fawning, unctuous kind of way.

‘What brings you over here, Charlie?’ he asked with an engaging grin. I explained and he said immediately, ‘I’ll go in the kitchen and get you some. It’s a bit of a madhouse in there today.’

He went away and left me alone in the dining room where I floated in a kind of sea of envy. Michelin stars are awarded not just for the food. Consistency, flair, the chef’s personality and the overall dining experience go into the mix. Strickland did not go in for minimalism. The King’s Head was classic. The furniture was flawless, the tablecloths heavy, ironed linen, the walls, some exposed brick and beam, others a kind of light creamy-grey alabaster effect. There was an eye-catching floral display on a table by the door, geometric in its execution. I contrasted it unfavourably with my shabby old tables and chairs, relics of the previous owner. I must do something, I thought to myself. Not for the first time.

Tris returned with ten pieces of star anise wrapped up in clingfilm. I could smell the heavy aromatic odour through the plastic. As he handed them to me, he said, casually, ‘You run, don’t you Charlie?’

‘Er, yes.’ It was true, I ran a few kilometres six days a week.

‘Me too.’ He hesitated. ‘Look, I’m starting a little local running group that will meet on Sunday mornings. It’s just for fun really. Your wine supplier Cassandra is coming, so you’ll know someone already. Are you interested?’

‘How far do you run?’ I asked. I had no wish to sign up to serious, agonising distances. He frowned, thinking. ‘Between five and ten k, certainly no more than that, usually nearer the five mark.’

I thought for a moment. I was certainly interested. I’m good at being self-motivated, but it’s easier if there’s a group of you. You stretch yourself more. I was conscious of the fact that I tended to do the same routes and the same times again and again. And it would be good for me to meet some other people for a change. I was in a rut, both in running terms and socially.

‘Yes,’ I nodded, ‘I am.’

‘Good. We meet on the common on Sunday at eight.’ He gave me a high wattage, professional smile. ‘See you then.’

Chapter Three

That Sunday morning was cool and grey, an unwelcome return to more usual British weather. We met up at 8 o’clock, as instructed by Tris, by the bench on the village green. Looking around me was like looking at an image from a picture-postcard book of a traditional English village: the green fringed by houses, and of course my café/restaurant; the play area halfway down the common next to the boundary hedge; the huge blue sky arcing overhead and views across the fields and woods to the neighbouring village, Frampton End. Trees and hedges marked the demarcation line to the adjacent meadow where horses were kept. Above us a couple of red kites with their distinctive V-shaped tails soared high on the thermals. At the bottom of the common, like a convention of undertakers, rooks and crows wandered around solemnly hunting for food.

There were six of us in the running group: myself; a guy called Matt who worked in IT; John, an elderly man in his late sixties; my wine supplier, Cassandra; a woman called Suzi; and Tris.

Tris introduced me to my fellow runners. ‘Cassandra you know.’

‘Hi Cass.’

‘Hi Charlie.’ She smiled her rather charming, slightly toothy grin. I had known Cassandra for over a year now. She was an independent wine supplier specialising in the unusual, more off-beat varieties from a varied group of countries. Since she’d taken over my wine list, sales had improved dramatically, as had customer satisfaction. I’m clueless when it comes to the stuff. I’m good with food, crap at wine. I can tell you the quality points of meat, fish and veg, I can sniff a ripe and ready to eat cantaloupe melon at 20 paces, but wine is a closed book to me. The only red I can recognise is the stuff served by the local pub, the Three Bells, because it’s so disgusting. Luckily, Cass knew her stuff. She was tall and slim, in her mid to late thirties, with long dark hair and large soulful eyes. Andrea, my Italian boyfriend, who likes art and knows a thing or two about it, said she looks like a pre-Raphaelite heroine. I hadn’t got a clue what he was talking about, so he brought up an image on his phone of women painted by some guy called Burne-Jones. Porcelain skin, long dark hair, soulful expressions. Yep, she did look like a Burne-Jones kind of girl. ‘A tragic heroine in the making,’ Andrea had called her.

Cassandra, or Cass as I usually called her, had a long jaw and a wide mouth; when she laughed (she didn’t behave like a tragic heroine, no matter how much she might have looked like one) she showed a lot of very white teeth. She wasn’t conventionally good-looking but she was very attractive. She was Strickland’s ex as well, which was interesting. I didn’t know the whys and wherefores (I had heard it said he had dumped her) but I can imagine finding life as Strickland’s girlfriend practically impossible. She was a real find as a wine supplier. Pre-Cassandra, my wine list was utterly uninspired, chosen by me on price and whether or not I thought the bottle looked nice. Now it was something to be proud of. Another interesting thing about her was that she was a wine dealer who didn’t drink. I never asked her about it, it was none of my business. When I was a kid I knew a boy who was training to be a butcher and he was vegetarian. It takes all sorts.

‘And this is Suzi… Charlie.’

‘Hi.’ Suzi was about thirty, Tristan’s age group. Everyone was, except me – mid-forties – and the old guy who was standing to one side watching on blearily with folded arms and sour disapproval. Suzi didn’t have a runner’s build the way Cass and the men did. She was sturdy, with a noticeably large chest. Good, I thought, that’ll slow you down. I knew that I wasn’t going to shine in this group but I didn’t want to be trailing along, way in the distance. She also had, like just about everyone these days – I was unusual in this respect being ink-free – a tattoo. It was a colourful hummingbird at the base of her neck. It was very pretty. Quite unusual, I thought.

‘This is Matt…’ Tris made an introductory gesture with his open hand. A tight smile from Matt, another thirty-something. He was tall and slender but muscular. I’d had a boyfriend once, very briefly, who had done calisthenics and I recognised the build, very strong but without the hypertrophy that say, a weightlifter or bodybuilder has. Matt was intimidating. He had a shaven head, not because he was going bald, you could see the dark stubble on top, but presumably because he liked it that way. He had slightly protuberant grey eyes and a reserved, quiet air. Despite this, or maybe because of it, he looked rather frightening, almost psychotic. But to be honest, what really stuck out were his shoes. Not literally, he didn’t have freakish feet, but he was wearing those shoes that have toes, like a glove has fingers. They were lime-green, Day-Glo; it looked like he had frog’s feet.

‘And, last but not least, John.’

This was the old guy. He wasn’t wearing hi-tech weird shoes, but he was wearing very short shorts, the kind that were popular in the 1970s. I guessed that he was probably a former club runner who had competed at some high level. He looked the kind, there was a certain rock-hard arrogance lurking under that ageing bodywork.

‘Hello John,’ I said with a warm smile, a smile that was not reciprocated. If anything the expression in his eyes was one of dislike. Sod you too, I thought.

‘Okay, guys,’ said Tristan with a warm, encompassing grin, ‘warm-up time.’

He led us in about five minutes of stretching exercises, lunges (boy do I hate lunges). I took a surreptitious glance at my fellows. Suzi was struggling like me, Matt kind of sprang from right knee bent, left on the ground to left knee bent, right on the ground, as if his legs were springs. His facial expression was one of calm concentration. It was a calisthenics move, very tough to do. I huffed and puffed.

Hip rotations, heel to butt, well, no problems there, ditto arm rotations. Tris had good biceps, Matt’s were like anatomical drawings. I knew that they were called biceps because they’re really two muscles, not one as you might think. You could actually see that in Matt’s arms, the divide was visible, he had so little body fat.

I carried on with my warm-up, quad stretches and ankle flexion. Tris certainly knew his stuff. After about five minutes more, we finished. ‘Okay, guys,’ Tris said, ‘we’ll be doing just a seven k today, a loop round Frampton End,’ this was the neighbouring village whose church spire you could see in the distance, ‘not fast, this is a slow run. Any questions? No? Off we go then.’

Just a seven k, I thought, mentally groaning. A couple of kilometres more than I usually ran these days. Well, I told myself, this was the point wasn’t it Charlie, you wanted to stretch yourself, you only have yourself to blame. We set off running down the common and then over the main road at the bottom, passing a lay-by that now contained a stained double mattress and some tipped black bin bags disclosing their contents of splintered wood and ripped up wallpaper. I wondered, as I always did, what kind of arsehole deliberately desecrates the beauty of the countryside like this for the sake of saving a few quid down at the dump. The problem was getting worse and worse, not simply with the fly-tippers (who at least had some kind of rationale behind their actions) but also the litter that pock-marked the sides of the road. Fast food packaging and cans tossed out of car windows. It enraged me, like gobbing in the face of Mother Nature.

I tried to forget this depressing reality as we turned up a footpath into a field. Our legs pounded along at a rate that was fast for me. We ran through Potter’s Wood, which lay between the two villages. The green leaves above our heads were a gentle, glowing sylvan cover over the track we were running along. It felt like being underwater somehow. As I ran, I reflected on the adjective Tris had used to describe the run. ‘Slow’ is a relative term. It may have been slow for the others, to me it felt anything but. To say it felt like a sprint, well, that would be an exaggeration but it was uncomfortably swift. Still, as I told myself, that’s what I was here for, to push myself, not to just plod along securely within my comfort zone.

I glanced at my fellow runners. Tris was leading but would turn around and shout encouragement to the two slowest, me and Suzi. John, the old guy, seemed perfectly happy, his hairless, skinny old legs effortlessly covering the ground, and Matt was, of course, running like a well-oiled machine, his expression a perfectly blank mask. Cassandra at first had seemed well within her comfort zone. Tall and leggy, she looked to have the perfect build, but as we approached the 25-minute mark she was starting to fade and fell in beside me and Suzi.

She grinned her toothy grin at me. ‘I’m not feeling it today, Charlie.’

‘Me neither,’ panted Suzi.

A significant gap was widening between us and the three men. Tris noticed it and must have said something because their pace dropped and he ran back to us.

‘There’s only a couple of k left,’ he said, joining us, ‘you can do it… just think of yourself as a car and drop down a gear… you can run a bit slower, it’s still running, we’re not trying to make the team.’ Obediently we slowed even more. There were some further encouraging slogans from Tris – ‘the only run you regret is the one you didn’t do’ – that kind of thing.

‘That’s it…’ Tris said, enthusiastically. Tris was certainly growing on me, none of the PE teacher about him. He must have been studying a manual of coaching psychology. It sounded very professional. We ran along a bit. Suzi’s breathing grew noticeably more laboured, unhappiness etched on her face.

‘There’s only one k left,’ he said, glancing at his watch, then looked at Cassandra and me. ‘You two can run off now, I’ll help Suzi over the line.’

‘You. Go. On.’ Suzi gasped, pain written over her pretty features.

‘Okay,’ Cassandra said, ‘see you back on the bench, Tris.’

We both accelerated away from the two of them as they settled down to a walk. Now we were alone, Cass turned the conversation to business and she told me about some incredible value South African wines that she had access to. They were a Cabernet Sauvignon and a Chenin Blanc that, because of the low value of the rand, were a really good buy.

‘I’ll bring them round when I call in at your place next time,’ she said. ‘Tris said he’d be interested too.’

I looked at her in surprise. ‘I didn’t know that you were supplying the King’s Head? I thought Strickland used someone else.’

‘Graeme uses a variety of suppliers. He likes to play them off against each other.’

I thought that was why she had avoided his restaurant, because of her hurt feelings. Maybe she was over that now, it must have been three or four years since they had split up. Almost certainly with his characteristic ruthlessness.

She may have guessed what I was thinking because she sighed and said, ‘We’ve obviously got a history, but I decided to let bygones be bygones. Anyway, I need the business. Tris is obviously more interested in the higher end of the market than you are, but he does like to keep a few cheaper wines for those who’ve decided they’re already spending enough as it is.’

‘Obviously,’ I said, without rancour. Strickland’s clientele could afford three or four hundred pound bottles of wine, mine certainly couldn’t.

‘Great, bring some round, I’m in.’ I had faith in her.

‘Okay.’ She nodded. ‘I’ll see you in the week; I’ll let you know when later today.’

So we finished our run and I walked the short distance back to the Old Forge Café, my restaurant and home. I made myself an espresso from the machine in the dining room, and was sipping it when there was a sharp knock on the restaurant door. I was surprised, my staff would go round the back, it was too early for customers. I walked over, unlocked it and opened it.

There was a man I didn’t know on the threshold. He had shoulder-length silver hair, a casual blue suit and an open-necked white shirt with no tie. He was stocky with a bull-neck. Short, but he had an air of almost aggressive self-assurance which counter-balanced it. My first impression was one of immediate dislike.

‘Are you Charlie Hunter?’ he asked.

‘Yes, but we’re closed,’ I said, firmly. I was suddenly very aware of the fact that I was dressed in sweaty running clothes. Not a great look for a restaurateur.

‘I know’ – his voice was sharp and to the point – ‘I’m not here as a customer.’

That threw me slightly. ‘Well what do you want then?’ I asked with a touch of asperity in my voice.

‘Your help,’ he said simply.

There was something in the way he spoke those two words that made me know he wasn’t talking about food.

‘You’d better come in,’ I said.

We went inside and I indicated a chair. ‘Please…’ He sat down heavily. I sat down opposite him and evaluated him. He was wearing expensive-looking ox-blood colour leather loafers with his suit. He had a bit of a gut on him which strained his shirt, not a good look. His face looked like one of the less crazy Roman emperors; he had the nose as well as the attitude. Imperious. Arrogance and latent aggression hung around him in a cloud as thick as his aftershave. If he had been there as a customer I would have put him down as the type likely to make a complaint, just for the hell of it.

‘So,’ I said, ‘how can I help you?’

‘My name’s David Summers.’

He had quite a coarse voice, London or thereabouts, none of the well-educated smoothness of Tris Smith. A working-man made good, I thought to myself. He was obviously making his own evaluation of me as he looked me up and down. I was conscious of the dark ring of sweat around the neck of my running top and under my arms. My hair was stuck to my scalp. I felt I looked a totally unprofessional mess.

‘And you are Charlie Hunter?’ Obviously making sure that this sweaty woman was indeed the boss.

‘I am indeed.’ I wondered where this was going.

‘You were recommended to me by Edward Hamilton.’ He looked at me questioningly as if a mistake might have been made somewhere along the line.

‘I’m…’ I said. Who? I tried hard to think of an Edward Hamilton but came up with nothing. David Summers noted my confusion.

‘The lawyer,’ he explained testily, in a tone that said, ‘Sharpen up!’

‘Oh, yes…’ I remembered now. He had been Lance Thurston’s lawyer, a slightly intimidating man. I’d rather liked him. Lance was a well-known podcaster who lived locally. I had done some work for him about a year ago, both a catering event, his birthday, and a personal matter; I had helped to get him off a murder charge.

‘Would you like to tell me what this is about?’ I asked, intrigued. Was I going to be hired for catering or to clear someone’s name?

I could hear movement now in the kitchen followed by music drifting through the door as Murdo started work prepping for Sunday lunch. I say, drifting, it was more of a thunderous racket. I recognised the gentle strains of ‘Life Sentence’ by Malevolence, one of Murdo’s latest enthusiasms. David Summers frowned. Perhaps he wasn’t a fan of metalcore. Maybe he would have preferred some Tool instead. I had become an unwilling follower of metal.

‘It’s about my daughter,’ he said.

‘What’s the matter with your daughter?’

‘Right now, nothing.’ He rested his hands on the table, the fingers bent over, the knuckles shining through the skin. ‘Nothing at all.’ He took a deep breath. ‘But I am very much afraid that her fiancé is going to kill her.’

My eyebrows arched, my eyes widened. That was unexpected.

‘What?’ I said, startled by what I had just heard. Especially the ‘going to’. Like it was a scheduled event.

Summers explained. ‘My daughter, Lizzie, is engaged to be married. I did some digging about her fiancé, I had my suspicions about him, and I think he plans to murder her.’

I frowned. This sounded terrible, but what did he expect me to do about it? I didn’t know his daughter and I didn’t know the man she was going to marry. I don’t know what David Summers was thinking, but I wanted no part of this.

‘Look,’ I took a deep breath as I backed away from the situation, ‘this sounds an awful situation for you and your daughter, but I’m not sure how I can help.’

He considered what I had just said and then, with the air of a man laying down a winning hand in poker, said, ‘This fiancé,’ a pause, a heartbeat, ‘he’s a friend of yours.’

I stared at him, confused, disbelieving. ‘What! Are you serious?’

He nodded. ‘Absolutely.’

‘Who?’ I asked. Various images of people I was close to flashed through my mind. My boyfriend, Andrea. DI Slattery, the policeman who lived across the common from me. My godfather, Cliff Yeats. The man sitting in front of me smiled bitterly and put me out of my misery.

‘Tristan Smith.’

Chapter Four

I opened my eyes wide in what I felt was almost a pantomime of surprise.

‘Tris! Are you sure?’ It seemed highly unlikely to say the least. Of all the people that I knew, this floppy haired former public-school boy seemed the unlikeliest candidate to be a killer.

Summers nodded. ‘Quite sure.’ He pointed a commanding finger at my coffee machine behind the bar. He had the air of a man used to being obeyed.

‘I’ll have an Americano and I’ll tell you all about it.’

I obligingly made him his coffee and an espresso for myself, the smell of the coffee drifting through the restaurant. The slightly chintzy decor and early morning sun made it an incongruous place for these revelations.

‘So, please go on,’ I said as I put the cups down on the table in front of us and took my seat opposite him.

And he did. It concerned Elizabeth Summers, his daughter. ‘Lizzie’ as she was known, was now coming up to her birthday. ‘It’s on the first of July; she’ll be twenty-four.’

‘What’s she like?’ I asked. He seemed puzzled by the question, threw out some generalities about his daughter, few of them flattering. Maybe he was one of these judgemental parents, but a kind of hostile judge. I gathered that she was not what you would call intellectual.

‘What does she do?’

‘She works at Stanley Wood eco-centre,’ he said. I nodded. I knew where it was, it was just off one of the neighbouring main roads; I had seen the sign for it probably hundreds of times. It lay at the bottom of a turning but it was a dead-end road that just led to the eco-centre.

‘What do they do there?’ I had always been curious.

‘They do stuff with schoolkids.’ He shrugged. ‘It’s an educational place. They take them on trail-walks, put up nest boxes, visit schools, that kind of thing. It’s all very commendable.’

He didn’t look like he was particularly happy about it. He’d managed to make the word ‘commendable’ sound like it was a bad thing. I was beginning to have my initial feeling that I didn’t like him justified. He was not overflowing with the milk of human kindness.

‘What do you do, David, may I ask?’ Something exploitative, I thought to myself.

‘Property,’ he said. ‘I make a lot of money.’ Ha! I thought, I knew it. He pursed his lips. ‘That is what attracted Smith to Lizzie.’

Silence. I was tempted to ask, the property or the money? Just to annoy him, but I didn’t.

I finished my coffee. ‘Go on,’ I prompted.

‘Look, there are some things that you need to know about Lizzie.’ He straightened up in his chair and shook his head for emphasis, then he pushed his fingers through his leonine locks. I was beginning to think he was a bit over-proud of his hair. Men are often self-impressed with weird things, like guys in bro T-shirts flexing their biceps to try and impress women. Summers’ barnet certainly didn’t impress me, my hair’s great.

Not content with the hair action, he pushed the sleeves of his jacket up so I could admire what I assumed was a very expensive wristwatch with several dials. I’m not keen on men with showy watches, I think it’s compensatory. I wondered what the different dials signified.

‘It pains me to say it, but she is not the brightest,’ he confided. ‘I had her tested. I thought maybe she was autistic or something, but no.’ I got the impression he would have liked her to be on the spectrum; she had disappointed him again. She didn’t have a rare condition, she just wasn’t very clever. I was beginning to feel a bit sorry for Lizzie. He continued. ‘She is though, extremely caring.’ He repeated the word for emphasis. ‘Caring, gentle and always trying to help.’

‘Hence the eco-centre,’ I said.

‘Exactly.’ He pulled a face. ‘Glis glis, hedgehogs…’

Last year he had taken her to a leading London restaurant for lunch on her birthday, and there she first laid eyes on Tristan Smith.

‘She started eating there regularly.’ He sighed. How could she afford it on her eco salary, I wondered. He noticed my interrogative glance. ‘She gets a good allowance. I later learned she was going back just to look at him. Eventually he noticed her…’

They started dating and they had been engaged now for about six months. The expression on Summers’ face made it clear what he thought of that.

‘They moved out here when he got the King’s Head job. I will freely admit he’s a persuasive little bastard. I think it suited him too because it got her away from her friends’ group; she doesn’t really know anyone out here apart from work colleagues. She’s isolated.’

‘And you think that Tris wants to kill her? Why?’

‘He is after money, Charlie,’ he said. ‘I’m a wealthy man.’

‘How do you know it is for your money?’

He gave a somewhat cold smile. ‘I’m a realistic man,’ he said, ‘I’ll be frank.’

I knew he would be. He was the kind of man who would say that, usually with great relish I guessed.

‘Look, Charlie, when I was younger – I won’t lie.’ He sighed. ‘Lizzie was a grave disappointment to me. I wanted a trophy daughter and I didn’t get one.’ Poor you, I thought, how dare she. How dare she not be stunningly attractive and bright. ‘But I’m nearly seventy, I’ve got a heart problem,’ he waved a hand, ‘stents… diabetes, I’ve had prostate cancer, I’m running out of road. Lizzie is all I have. When I go I can’t look after her. I can’t protect her. This needs sorting out now.’

‘Okay…’ I said in an unconvinced kind of way.

‘Before it’s too late.’

‘I see.’

He carried on. ‘He’s very good-looking and my daughter isn’t.’ Summers said tetchily. I frowned. Surely there was more to a relationship than this. He continued the ruthless demolition of his daughter’s looks by seasoning it with a sprinkling of self-awareness. ‘She inherited my looks, not her mother’s and she’s going to inherit my money. That’s the problem.’

‘Is that a problem though?’ I tried to put across my point. ‘Surely, attraction doesn’t depend purely on looks. And why shouldn’t money be as valid a reason to find someone as attractive as, say, personality? Both rely on a certain amount of luck, don’t they?’ I warmed to my theme. ‘You can be born pretty or rich or with drive or brains, it’s down to chance. You play the hand that life has dealt you.’

He nodded. ‘There’s a certain amount of truth to that,’ he admitted. ‘Ordinarily, maybe I’d have gritted my teeth and let things be. I could have accepted that, that he was interested in her money.’ He sighed again. ‘And if he was a good enough husband, gave her a couple of kids and a happy home life, well, I would have thought, okay I’ll pay for that… but for one thing.’

‘What one thing is that?’

David Summers settled back in his chair. ‘Could I have another coffee?’

‘Sure.’

I went round the bar and made him a second Americano then brought it to him and sat down. He sipped it appreciatively and smoothed his hair again. Maybe he thought the coffee would be good for it.

‘I can understand what you’ve been saying,’ I said, ‘but what makes you think Tris is so mercenary? And even if he is after her money, why do you think he wants to kill her? Maybe he genuinely loves her.’