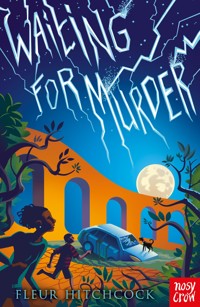

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nosy Crow Ltd

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

Shortlisted for CrimeFest Awards' Best Crime Novel for Children 2019 When Viv has a fight with Noah, she doesn't think it'll be the last time she sees him. But when she gets back from school, he's nowhere to be found and there are police cars everywhere, lights flashing and sirens blaring. Viv is sure Noah's run away to get attention. But it's really cold, and getting dark, and the rain just won't stop falling. So she sets off to look for him, furious at his selfishness, as the floodwaters rise. And then she finds him, and realises that a much more dangerous story is unfolding around them... From the author of Dear Scarlett, Saving Sophia and Murder in Midwinter "The story creeps in on you like darkness at dusk - a truly intriguing mystery!" - Chris Bradford, author of the Young Samurai series

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 233

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For the Children of Abbots Worthy

Prologue

I’ll start at the beginning, because that’s what you’re supposed to do.

Although that would be me falling in the river when I was two and him falling in afterwards because he thought I was waving, not drowning. That was the first time I met him.

Apparently.

No, I’ll start at the second beginning.

The one before where it all kicked off.

That one.

Chapter 1

Mum and I are having the same row we always have. About changing the way we live. I want to change everything; she doesn’t want to change anything.

“For goodness’, sake, Viv!” says Mum, lobbing her tea bag into the sink. “There’s no point in you taking the bus. I’m already driving past your school on the way to Noah’s!” She bangs her mug on to the kitchen table. “And that – is that. Now, are you ready?”

“Why doesn’t Noah take the bus too?”

Mum doesn’t answer.

“Because he’s too precious – that’s why, isn’t it?”

“Stop it, Viv. It’s all hard enough without you–” Mum shakes her head from side to side, “making it worse.”

Tai, our dog, yaps and dances around the table legs. He thinks we’re playing.

Too angry to even stroke him, I yank up my tights and jam my feet into my battered school shoes without undoing the laces. It’s always like this. We always please them. We’re always going to have to fit in with the Belcombes. Because Mum was Noah’s nanny. Mum wiped baby Noah’s bottom, read baby Noah his bedtime stories, patched up baby Noah’s cuts and bruises. She still drives him to school, buys his clothes, makes him practise the violin. Noah is Mum’s job. I’m – well, I’m me.

I shoulder my school bag.

And he’s super precious because he’s the last of the family line. There isn’t another one. Noah Nathaniel Simeon Belcombe, only child, otherwise known as Viscount Alchester, is first in line to the family throne. He’s an endangered species.

I’m plain old Vivienne Lin.

I crash through the kitchen door, letting it slam back against the wall, and stomp down the stone steps into the leaves swirling around the main courtyard.

“But you didn’t even touch your toast!” shouts Mum behind me.

At the top of the steps Tai tilts his head to one side, looking hopefully at my breakfast sagging in Mum’s hand.

I don’t answer.

“Viv! You’ll be starving by lunchtime.”

I still don’t answer.

Behind me, Mum sighs.

“Bye, Tai,” she says, closing the door to our little flat above the old stables and sweeping past me to the shiny green Mini parked on the gravel in front of the main house. Lights flash and the Belcombes’ third car makes a smug little electronic bleep as she unlocks it.

“Get in, please, Viv,” she mutters.

I lean on the front passenger door and slowly her eyes come up to meet mine. “Back seat, please, Viv. Now, please.”

I stay put, conscious that defiance is making me tremble slightly, and I wait, still leaning on the outside of the car, while she lets herself into the big house and comes out a moment later, followed by Noah, gleaming in his dry-cleaned St David’s uniform, his new shoes polished, his blond curls brushed into a golden froth.

“Morning, Noah,” says Mum, pulling a tight smile.

“Morning, Marion,” he says, coming round to the front of the car and nudging me out of the way, before yanking the door open and throwing his school bag inside. Following the bag, he squeezes himself into the front seat and immediately starts to fiddle with the stereo.

“I wonder,” says Mum, standing at the driver’s door. “I wonder if you two could manage a journey, together, in the back?”

“What?” says Noah, his stupid forelock of curls flopping over his face. “But I always sit in the front!”

“You do at the moment,” says Mum, super calmly, “but you didn’t used to – if you remember, it’s only been a month … since you…” She stops.

“Since you threw my bag out of the window on the main road,” I add, my arms tightly folded. “And didn’t get out to pick it up, and didn’t apologise.”

“Viv,” snaps Mum. “So I thought we could return to the way it was before. The two of you together, getting on nicely in the back.” She hesitates. “It’s fairer.”

Part of me wants to whoop with joy. Mum, standing up for my rights over the little lordship, holding a valiant flag up against the tyranny of the family that has everything. And part of me wants to climb into the boot and sit in the dog hairs to avoid sitting next to him.

He’s a bully and I don’t want to share a seat.

If he could disappear, right here, right in front of me and Mum – I wouldn’t shed a single tear. I’d laugh.

“No,” he says, clicking his seatbelt across his chest. “No. I won’t.”

Mum’s jaw drops open.

“Noah Belcombe. Would you please sit in the back of the car so that Viv can sit next to you. Please.”

He gets out his iPhone and starts to swipe through his photos.

“Don’t worry, Mum. He’s just a pig – an inbred pig,” I say, walking round to the driver’s side and pulling the seat forward. “I wouldn’t sit next to him if you paid me.”

Noah swings round as I’m about to get into the seat behind him. “Take that back, you little –” And he lunges for my hair.

I’ve got faster reactions than him – always have had – and I thrust my hand out to stop him, but the outer side of my palm connects with the underside of his nose.

“Ow!” He yowls and blood explodes across the car.

“Oh, god! Viv – Noah – stop it!” says Mum, reaching for tissues.

But actually, I don’t want to stop it and I punch Noah’s nose just a little bit more, so that the blood sprays down the front of his trousers.

Mum jumps into the front seat and closes the door. I don’t think she wants Noah’s parents to see what’s going on in the car, although in the last ten years we’ve had some pretty spectacular fights – and she can’t have kept them all hidden.

“Oh, no.” She dabs at him with kitchen roll that she finds in the glove compartment. “Oh, Viv – you idiot.”

“Not my fault,” I say, settling back, feeling horrible mixed emotions about Mum scrabbling to clean Noah’s face balanced with enormous satisfaction in having caused him so much discomfort.

“You’re dangerous, you are!” Noah splutters, pinching the top of his nose to stop the blood.

Mum looks anxiously at the fall-out. A mass of bloody tissues and kitchen roll bounce across the car. Noah’s white shirt is still white, but his jacket has dark marks on it; his bag too. “It’s not too bad,” she says, starting the car and rolling gently out of the drive. “It’ll stop in a minute.”

“Not bad – I should call the police on you!” he says, jabbing his finger in my direction.

“Oh, yeah,” I say. “Like calling someone inbred when they come from one of the most inbred families in the world is wrong? I’m just being scientific. The gene pool in your ridiculous family must be—”

“Shut up, Viv,” barks Mum. “And apologise.”

“I didn’t do anything,” I say, crossing my arms and staring out of the window. “He started it. He wouldn’t share.”

“Silence! Both of you!” yells Mum as we pull out on to the road.

No one speaks as we glide through the woods down the long, long drive. Connor Evans, the gamekeeper, is stoking a bonfire on the edge of the grass and he waves at us. None of us wave back. I would, but honestly, I’m too angry. Mum pauses as the electric gates open and we pull out into the lane, leaving the Blackwater Estate behind. The village flashes past and soon we’re in the suburbs of Alchester. Mum negotiates the traffic and still we sit in silence, listening to the tick-tick of the indicators. Noah texts me.

I’ll get you later, he says.

In your dreams, troll I text back.

And the beginning of the chain-link fence that surrounds my school appears on our right.

We approach Herschel High and Mum pulls into the usual lay-by, leaps out and tips her seat forward. Without a word to Noah, I clamber out.

“Bye, Mum,” I say, turning my back on the car and walking into school, ears burning, face burning, everything burning.

Chapter 2

I’m still furious when I bump into Nadine, Sabriya and Joe by the bus shelter. Nadine takes one look at my face and says, “Noah?”

“He’s a…” I can’t actually think of a word.

“An amoeba,” says Joe.

“A slug,” says Sabriya.

“A school sausage roll, with school gravy,” says Nadine.

“A school-mash-and-roast-beef smoothie,” says Joe, and they laugh. Although I don’t, because inside, I seem to have lost my sense of humour.

“Yes,” I say. “He is. He’s all of those things.”

We join the living stream of Herschel High students pouring in through the gates. The two-minute bell rings.

“Hey, Viv, you’ve got ketchup or ink or something on your hand,” says Joe as we spill into the corridor.

“Oh! Yuk.” I wipe it off on my bag. “It’s Noah’s blood. I actually punched him.”

Sabriya raises her eyebrows. “Noah’s blood – for real?”

I nod. “Yup,” I say, a blush racing up my face. “And he bled like a … a…”

“…pig?” suggests Joe, shoving me towards my tutor room, just as the bell begins to ring.

* * *

“Vivienne Lin!” calls Miss Parker.

“Here,” I say.

She marks me down in the register and I look at my timetable. Double Maths next. OK, I can do this. I’m not bad at maths, and if I want to become an architect, I’ve got to get a good grade. If I could just get Noah out of my head and start breathing properly everything would be fine.

I peek down at my bag. There’s the dark stain from his blood. I wish I’d spotted it earlier – I could have washed it off before Tutor.

Mindfulness – isn’t that what they call it? I stare out of the window. Autumn sunlight streams through towards me, blinding me. I try to concentrate on the little scraps of dust floating in the sunbeams. I try to control my breathing but an image of Noah’s curly blond hair, catching the sunlight, creeps into my mind. The hair thing’s always happened, and when we were little, all the adults would go ahhhh. How sweet, and then they’d look at me sideways and say, I bet she’s clever.

Well, I am. I’m cleverer than him, I always have been, and I haven’t had any of his advantages. For a start, I’m here at crummy old Herschel High – not perfect St David’s. I’m plain old Vivienne Lin, he’s Viscount Alchester – lord-of-the-manor-to-be. Then there’s the squillions of acres and the whole feudal thing of everyone treating you like a lord. It’s like a place that got stuck. No one can ever leave working there because they live in houses that belong to the Belcombes and there are no other houses to live in because the Belcombes own everything for miles. It’s like everything you ever earn goes back to the people you earn it from. I’ve heard them all complaining, especially the people with large families to support – they have to rent bigger cottages, which means more rent, less money left over. That’s why I want to be an architect and build affordable housing for me and for others. And I want to build my own modern house on my own patch of land. I want to be my own person.

My mindfulness has flown straight out of the window and I look down at the bloodstain on my bag. I wonder if his nose is still sore? I feel a slight twinge of guilt. Very slight. Noah does get nosebleeds. Always has. But they’ve mostly been to do with altitude, not fists. Examining the back of my hand for spatter, I think of all the blood shooting out across the car – there was a lot. It was spectacular.

The bell rings and we fill the corridors, queuing to get into lessons, blocking the doorways. To get to Maths I’m going to have to go past the toilets, so I rush along the corridor and dive into the ladies’, running my bag under the cold tap and washing my hands with a thick glob of pink goo soap. It takes minutes rather than seconds so I get into Maths after everyone’s sitting down.

“Nice to see you at last, Vivienne,” says Mr Marlow, swinging in his chair, arms raised above his head revealing two perfect circles of sweat on his checked shirt. I try not to look, or sniff, but can’t help myself and begin to laugh as the stale sweat reaches me. Maths is hard enough without this.

“Can we open the window, sir?” I ask.

“Just sit down, please, Vivienne,” he says, leaning forward and clunking his chair.

“But,” says Sonny next to me, “it’s really hot in here, sir.”

“Yes, sir,” says Juliet. “I can hardly breathe.”

“Yes, sir – it’s like, boiling in here,” says someone.

“So stuffy,” says someone else.

“Can we at least take off our jackets?”

“Sit down, please, Vivienne, and quiet, everyone,” says Mr Marlow, his arms down, the offending armpits out of sight, but not out of smell.

“But, sir,” I say. “Windows, please, sir – or we won’t be able to concentrate.”

Mr Marlow stands and points at the clock. “I’ve wasted seven minutes of my life waiting for you lot to be lesson ready,” he says. “Seven minutes. That’s seven minutes I won’t get back.” He sits on top of his desk and taps his fingers against the side.

“And I’ve wasted seven minutes of mine breathing in your stinking armpits,” I whisper, slightly too loud in the sudden silence.

* * *

I don’t really mind detention. Apart from anything else it means I won’t be stuck in the car going home with Noah. I text Mum to tell her I won’t be ready on time and she texts back an emoji of a bus.

Fair enough.

Today, we’re litter-picking with Señora Delgado. She’s actually lovely and when I tell her how I ended up in detention, she laughs. “Oh, you are so naughty, Vivienne. Poor Mr Marlow.”

But because detention overruns, I miss the late school bus.

That means I’m going to have to walk into the centre of town. And catch the ordinary bus home.

And the beautiful sunlight that’s been streaming all day suddenly fades, and it feels like winter and I wish that I’d eaten the toast Mum made, or grabbed my bobble hat or gone home at normal time in the car.

A police car screams down the road towards St David’s.

Shivering, I clutch my jacket across my chest and hunch up my shoulders. There isn’t much wind but it feels as if there is, and the cold creeps in through my neck and my cuffs and everywhere. Tights just aren’t enough protection when the temperature’s plummeting and my legs turn to lumps of ice.

By the time I reach the bus station, I’m frozen.

I get out my phone and send Mum a text to say I’ll be on the next bus, but she doesn’t reply.

Then I send Nadine a photo of my frozen feet.

She sends me one of her feet in slippers on her duvet.

I send her one of the scary woman in pink sitting on the line of chairs.

She sends me one of her cat.

I send her a selfie of my head against the announcement board.

She sends me one of a cheese toastie.

The bus comes and I have to wait while thousands of people with bus passes fill all the easy seats.

I sit at the very back and slowly warm up as the bus wanders through the edge of town. Then the house lights fade away and it’s just cold countryside out there.

We stop in Easton Abbas. An old woman with a trolley slowly shuffles to the front of the bus and gets out. She vanishes in the gloom and the bus pulls away, lunging through potholes, speeding around the bends in the road, and tossing me back and forth along the back seat until I feel sick. Finally we rumble into Blackwater Abbas, where I ring the bell and lurch down the middle towards the door. No one else gets off and I’m surprised to see the reflective strip of a police car caught in the bus headlights as it slips past. There are never any police around here. Nothing ever happens.

I wait as the bus pulls away, the roar of the engine and the glow of the rear lights vanishing in the direction of Lower Marston. Pulling up the collar of my jacket, I run past the few houses and along the footpathless lane as far as the gates of Blackwater House. There are no lights, but I’m used to this road in total darkness. And it isn’t totally dark, there’s a candy sunset streaking the western sky. Reaching the gates, I stop and punch in the entry code. With a groan they open and let me through.

An owl hoots.

The light from my phone seems over-bright as I text Mum.

Any chance of a lift from the gates?

But there’s no answer, so I try ringing. Again, no answer. It goes to voicemail straight away. That’s odd. Mum keeps her phone switched on all the time. In case of Noah. He may not be four any more, but he still seems to need her holding his hand.

She’s probably helping him with his homework. Or taking his jacket to the dry cleaners.

Putting my phone back in my inside pocket, I pause for a moment, listening to crunching noises all around me. At first I can’t work out what they are, and then I realise they must be ice crystals forming. My jacket has no more warmth to give. No amount of dragging it across my chest is going to make any difference, and the pockets are stupid not-real ones so all I can do is jam each hand inside the cuff of the other sleeve and clutch my arms across my chest. It’s like wearing a cold straitjacket.

Off to my right are the glowing remains of Connor’s bonfire, and for a moment I stand with my toes in the ash, hoping the feeble embers might do something to warm me up.

They don’t.

Right now, I’m kind of regretting that detention. I could have come home with Mum and Noah in the Mini. Instead, there’s the whole drive to walk. Though – I glance off to the left – there are the bushes; I could take a short cut. Leaving the fire and brushing through the beech hedge, I strike out over the lumpy verge where there’s a kind of badger footpath. The ground crunches under my feet and when I look up at the sky it’s perfectly clear and there’s a star already twinkling. It’s going to be seriously cold tonight.

The hedge closes behind me and I navigate using the tops of the trees silhouetted against the greeny-orange sky. There are fewer of them to the right, which must be the path to get to the house. Although I’m fairly sure of my way, branches thwack against my face and drag at my clothes. It’s been some time since I tried to come through here and I wonder if I’m going to walk into a wall of brambles. I must have been with Noah last time. It must have been one of our getting-on moments. I’d convinced him that there was a ghost living here, in the drive woods. We sat for hours waiting one night until a badger appeared and spooked us. We ran home screaming.

As I approach the house I’m met by flashing blue lights. Police? Here?

Three squad cars fill the courtyard outside the house and there are some massive lamps floodlighting the Mini. People in white all-over suits are rummaging inside and underneath it. They’ve set up a white plastic gazebo and the lights are so strong it looks like a film set.

“What’s going on?” I say to the air.

This is not normal.

Chapter 3

No one seems to notice me, and I pause at the entrance to the courtyard, trying to decide whether I should go up to our flat or talk to a police person or try the doors of the big house.

In the end, I decide to try the flat. The door’s unlocked, it’s nice and cosy, but there’s no sign of Mum. Instead, Tai bounces up to me, his tail wagging. He yaps and trots over to the back door so I let him out down the back steps to wee in the stable yard.

“What’s going on, Tai?” I ask, resting my hands on the radiator. “Why are the police here?” He answers by squeezing back in through the gap in the door, rolling on to his back and squirming around until I rub his tummy. “And where’s Mum?”

Flipping back on to his feet, he examines his empty food bowl, prodding it with his nose and making sad noises. Eventually, he pushes it right across the floor and looks up at me. Hopeful.

“You haven’t been fed?” I say, finding half an open tin of dog food in the fridge. It looks like the same tin of food Mum opened this morning. “You really haven’t been fed – you must be starving.” Prising the lid open I spoon out the disgusting jellied lumps. “Here.”

Tai snuffles around me and makes extravagant eating sounds. I rub his ears and the food vanishes in seconds. “What have you done with Mum, eh?”

While he licks the bowl clean I wander over to the little window next to the front door and peer out through the slatted blind into the courtyard. I don’t think anyone can see me, so I watch for a few minutes, trying to make sense of everything. The people in white are very busy sticking things into bags, and one of them is crawling across the tarmac on their hands and knees with their nose about an inch above the ground.

If it wasn’t really disturbing it would be funny.

As I stare out, the front door at the top of the steps to the main house opens, and framed in a rectangle of orange light is Sharon, Chris the waterkeeper’s girlfriend. She’s looking down at her phone, so I can’t really see her expression because she’s got this long blonde hair that hangs down in a sheet on either side of her head. Behind her comes Dave McAndrew, the man from the sawmill, and Connor Evans, the gamekeeper, both looking worried. They’re followed by Lord Belcombe and Chris himself. They all bundle into the Land Rover and sweep out of the courtyard.

Then Lady Belcombe, Noah’s mum, appears at the top of the steps, watches the white-suited people for a moment, checks her phone and goes back inside, without closing the door properly.

“What shall I do, Tai?” I ask, stepping back from the window.

In answer, Tai lies down, crosses his paws and rests his head on my foot.

“I need to do something, I can’t just stand here waiting.” I don’t usually go into the main house, but I really want to find out what’s happened – and if anyone asks, I’ll say I’m searching for Mum, which I kind of am.

A little bit terrified, I run down our steps, cross the courtyard and walk up the grand marble steps that lead to the house. I know Lord B’s out, I saw him go, but Lady B’s not easy. Mum’s very good with her but she can be scary, mostly because she’s used to people following her orders. She ran a newspaper or something before becoming a Belcombe. She doesn’t fit here in the middle of the countryside. I don’t think I’ve ever seen her outside unless the sun’s shining. She’s too towny and she probably knows it. Maybe that’s why she’s so prickly. Perhaps country people make her feel uncomfortable.

Or am I kidding myself?

The heavy oak door swings open as I touch it and I stick my head around. It gives straight on to the hallway – which is really a giant open barn thingy, as big as most people’s whole houses, with a fireplace, sofas and a table. Portraits of ancient Belcombes line the walls and the corners of the room disappear in polished wood murk.

Lady Belcombe is standing in front of the fireplace, her face streaked with tears. When she sees it’s me she rushes forward to grab my arm. “Vivienne, darling, I’m so glad you’re back. Have you heard anything from little Noah? Have you seen him? He hasn’t come home, he wasn’t there when Marion went to pick him up, and…” She shakes her head as if there’s something more she’s not going to tell me. “I’m so worried about him.”

“What?” I say. “Mum went to pick him up from school and he wasn’t there?” I try to keep the excitement out of my voice. This is thrilling on many levels.

“He’s vanished,” she says, sniffing. “Has he contacted you?”

I reach for my phone. “No,” I’m saying already. “No – not as far as I know, nothing.” I hold it up. Apart from this morning’s I’ll get you later, the last message from Noah was six months ago, when he’d sent me the charming words, Suck it up, loser.

That probably marked the absolutely final end of our not very beautiful friendship.

“Vanished – like, disappeared?” I say. She’s not listening to me though.

A policewoman comes out of the sitting room and takes Lady B by the elbow. “Shall I make you another cup of tea?” she asks.

“I’ve had enough of tea, you stupid woman,” Lady B snaps, and then, as if remembering that she’s talking to a police officer, she says, “No, no thank you very much,” sniffs and sinks into one of the monumental leather sofas, trembling and blowing her nose. “Vivienne, sit down and help this woman find my son.” She points at the other vast sofa, one that must have seen the death of several cows.

Ignoring everyone, Tigger, the Belcombes’ cat, struts over and wipes his head on my shin then sits and licks his chest. I bury my hand in the thick fur behind his head and try to feel normal. Because she’s told me to, I sit down, but it feels surreal sitting here with Lady B and the cat.

“Ah – Vivienne? Vivienne Lin.” Not at all bothered by Lady B, the policewoman checks a notebook. “You live here, don’t you?” she says. “We need to talk to you.”

“What’s happened to Noah?” I ask. “Where’s my mum?” Tigger leaps from the floor and settles on my lap, purring.

“Your mother? Oh, yes, she’s showing one of my colleagues the route she took to St David’s this morning. As for Noah, we’re just checking every avenue at this stage.” The policewoman delivers a glowing smile. “As you’re sitting down, would you like to talk here? Just an informal chat. We’re trying to establish one or two things about him – his interests, that sort of thing.”

Of course I’ll answer questions. Anyway, I don’t suppose I have much choice.