Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nosy Crow Ltd

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

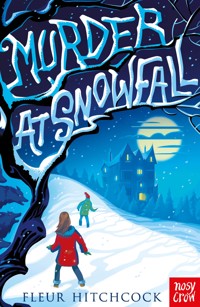

Sitting on the top deck of a bus days before Christmas, Maya sees a couple arguing violently in the middle of a crowded Regent Street. They see her watching, she looks away, and the woman disappears. Maya goes to the police, who shrug and send her away. Then a body turns up... Now convinced she is a vital witness to a crime, the police send Maya into hiding in rural Wales. She resolves to get to the bottom of the mystery. Then the snow comes and no one can get out. But what if someone can still get in? From the author of Dear Scarlett and Saving Sophia. "Fleur Hitchcock... has cornered the market in hard-boilers for beginners." - Alex O'Connell, The Times "A taut and exciting thriller. Fleur Hitchcock beautifully captures Maya's sense of unreality and fear as she untangles family relationships along with the mystery." - Scotsman "For a young readership, this is surprisingly no-holds-barred, but it handles a potentially traumatising subject with just the right balance of tenderness and gusto." - The School Librarian

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 214

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Ruby

Chapter 1

The bus stops for the millionth time and I look down at my phone for the millionth time.

A little envelope appears in the corner of the screen. I click on it.

It’s my sister, Zahra.

What you gonna wear to the party?

Staring out of the window at the thousands of people stumbling along the pavement I imagine my wardrobe, mentally discarding clothes that I can’t possibly wear to the end-of-term party: too cheap, too old, too “princessy”.

My green dress? Just right. Not sure about shoes though…

Dunno. You? I text back.

Dunno, she replies. The bus creeps forward. There’s a long pause from Zahra.

My phone buzzes again.

Can I borrow your black jacket

We judder to a halt. There are even more shoppers now, in layers. The ones nearest the bus fall on and off the kerb, jamming along faster than those in the middle who struggle past each other, pulling their shopping close, their faces grey under the street lights.

In x change for purple platforms I type.

I press send and a huge woman comes and lands her enormous bottom on the seat next to me. She’s got a ton of shopping and she’s too hot and I can see a bead of sweat trickling down her skin just in front of her ear. She’s damp. Hot and damp.

She glances at me, and then looks away. Then looks back again.

“Unusual that,” she says.

“What?”

“Mallen streak, it’s called, isn’t it?” She puts her hand up to her hair. “The white bit.”

I nod. I know it’s unusual, but I like it. It makes us special, me and Zahra and Dad. Black hair, white streak. Hereditary. Like skunks, or Cruella de Vil.

The bus makes a dash over a set of lights and I find myself staring at a new set of shoppers. We head towards one of the huge Christmas window displays and I get my phone on to the camera setting so that I can take a picture for Zahra. It’s difficult to get a decent shot, there are so many people in the way, but I hold it up ready to click. We judder to a halt and I start taking photos even though the windows are slightly further ahead.

Click

Flash

Click

Flash

Click

Click

What was that?

Click

Looking through the viewfinder, I see a man. He’s in a gap in the crowd. He’s tall, with curly hair. Ginger hair, I think. Everyone else seems to be rushing past him but I notice him because he’s standing still. There’s a woman there, she’s still too. They’re arguing. He disappears as the crowd swirls around him. A couple with shopping bags swing across the view, some kids, a large family, but my eye goes back to the man the moment he reappears.

Click

Click

He’s holding something.

Click

Is that a gun? He’s drawn a gun on her?

I keep taking the photos, and the flash goes off half the time and then the man looks at me and so does she. I take another photo and he runs and the bus pulls away, stop-starting through the crowds all the way down to Piccadilly Circus.

I stare back up the pavement but I can’t even see the lights of the department store now. The woman next to me gets off, and a bloke reading a book gets on. It’s all really normal, but what have I just seen?

Was that a gun or not?

I flick through the photos.

There are quite a few where the flash just reflects on the window, one really good one of the window display, and then three blurry pics of the man and the woman. Two from the side, one straight on, looking right at me. I zoom in on his hand.

Definitely a gun. Or definitely the barrel of a gun.

A man holding a gun? In Regent Street, ten days before Christmas.

The time on the photo is 17.14. It’s only 17.26.

I swallow, feel sick, excited then terrified. I doubt myself.

But he did have a gun. I’ve seen enough movies to know that’s what he was holding.

The bus swings down towards Trafalgar Square. People pile on and off and I look at the pictures again. I text Zahra.

I’ve just seen something really weird – scary.

What?

A man with a gun on the street.

I look around on the bus to see if there’s a policeman. Or should I jump off and look for one on the street?

Whaaat? Are you OK?

Yes – I’m OK. I type, but my hand shakes and the phone shakes with it.

Come home, says Zahra.

Waterloo Bridge whizzes by and I jump off at my stop and wait, shivering, for the next bus to take me home.

Chapter 2

The huge windows of our shop illuminate the pavement and light up the underside of the railway bridge that crosses the road. This time of year, it’s all made brighter by a host of random flashing Christmas lights that Dad’s wrapped around everything possible. The really posh bath in the window manages to look utterly bargain basement, festooned with tiny glowing Santas, and he’s jammed the matching £600 toilet with miniature reindeer lamps. It’s all going on and off all over the place, but it makes the shop look warm and welcoming, even more warm and welcoming than it does normally.

I rush in, desperate to talk to Zahra. She’ll be upstairs, but I have to pick my way through the shop to get there.

Azil’s in the showroom, discussing copper piping with a man in overalls, and Mum’s trying to persuade a woman that the cream bathroom suite that’s been in the middle of the shop for two years would look brilliant in her new loft conversion. It’s so normal in here it feels unreal.

Granddad comes through from the kitchenette. I could tell him?

“Granddad,” I say.

He’s behind the till now. He holds up a finger and points to the phone.

“Just a sec, Maya darlin’,” he says. “Yes, Michael, seventy quid each – but I can do them at sixty-five if you take all three? What about it?” He pauses, his finger still held up to keep me silent. “Yes, so Tuesday? Cutting it fine but they should be here by then … well sixty each OK, but you’re breaking my heart, Michael, you know that…”

Granddad listens, his head nodding, as he scribbles something on the corner of an envelope before tapping an order into the computer.

I can see he’s going to be more than a minute so I squeeze past a pregnant woman, who’s admiring a mirror that plays three radio stations, and push through a stack of cardboard into the kitchenette.

The twins are sitting on the floor peeling coloured wrappers from a giant tin of Quality Street.

“My,” cries Ishan.

“My,” echoes Precious.

Precious offers me a naked toffee, spreading the yellow wrapper over her eye and staring at me through it.

“Thank you, Precious,” I say. “But d’you know, I think I’ll pass this time.”

“Maya!”

I look up towards the door that leads up to our flat. It’s Zahra. She looks exactly like I did two years ago. Same black hair, same streak of white front to back.

“What happened?” She takes the toffee off Precious and jams it in her mouth.

“I just saw him.”

“Was he threatening anyone?”

“Well yes, this woman … I’ve got a picture here, somewhere.” I pull out my phone and click through the images. “Look.”

Zahra peers over my shoulder. “What am I looking at?”

“There,” I say, expanding the image to show the glint between the two black coats.

We stare at each other. Her black eyes looking back at mine. Reading each other’s thoughts.

“Tell Mum,” she says in the end.

I stick my head back past the cardboard into the shop. Mum’s on her own with a box of toilet joints. “Twelve, thirteen, fourteen,” she counts, dropping them into a wire basket.

“Mum,” I say. “Can you talk?”

“Course, fifteen, sixteen, seventeen.” She folds over the top of the box. “What is it?”

I look around at the aimless customers lifting up toilet seats and turning display taps. “Can I tell you upstairs?”

Mum’s face goes from unconcerned to concerned in a millisecond. “What is it? What’s happened?” She bustles behind me, shoving me past the cardboard, around the twins and up the stairs until we burst into our flat. “Tell me,” she says, flumping into an armchair and giving me all of her attention. “What’s happened?”

“I want to ring the police,” I say.

“What? Why?”

I show Mum the picture. It takes ages to load. It’s a rubbish reject phone of Dad’s, but it’s still a smartphone.

Her mouth drops open. “Is that what I think it is?” she says, reaching for Granddad’s extra-strong specs. “Blimey,” she says looking up at me. “What happened next?”

“The bus went on, and I left them behind.”

Mum puts my phone on the table and stares out of the window into the flats behind.

The twins scrabble up the stairs and thump off to their room.

“Well,” says Mum, “you’d better use the landline.”

* * *

“Hello? Police please.” I’ve never rung the emergency services before, and it makes my heart go poundy. “I want to report something I saw earlier.”

The woman on the other end is in a call centre full of noise that I can hear in the background. Someone near her says: “The ambulance is nearly with you.” And I wonder whether I’ve rung the right number.

“Are you in danger?” asks my operator.

“No, I’m at home, safe.”

“Can you give me your address?”

I give her my address, tell her I’m fine, but try to explain what I saw. “He had a gun.”

“How old are you?”

“Thirteen – why?”

“Can you get an adult to make this call?”

“No – because I was the one that saw it.”

There’s a pause.

“What time was this?” asks the operator. I check my phone. “About quarter past five.”

“Thank you caller, I’m transferring you.”

So I run through the whole thing again. And I’m transferred again. And I stop feeling panicky and begin to feel somehow stupid and actually cross. By the third transfer I’m sitting cross-legged on the floor, pinging the elastic on my tights but I don’t put the phone down because that would be giving up.

“Yes,” I say when I finally get through to someone who listens. “I saw a man with a gun in Regent Street.”

“And you recorded this?”

“Yes, sort of, on my phone.”

“What time?”

I don’t need to check again. “Quarter past five,” I say.

“We’ll send someone just as soon as we can,” they say, and I put down the phone hoping very much that I’ve been taken seriously.

Chapter 3

I hold up my hand. It’s still shaking.

“Thing is, Granddad, I don’t think I’ve ever seen a gun before. I mean a real one.”

Granddad nods. He’s listening to me, I can tell – but he doesn’t answer. Instead, he reaches into a cupboard and pulls out an oily cardboard box. “Let’s do a bit of work on the old motorbike, take your mind off it while we’re waiting.” He hands me a pot marked valve paste and a mushroom-shaped piece of metal. I take a blob of the paste and rub it gently into the metal, smoothing away the old carbon. I could use a drill to do this, but I prefer doing it by hand.

“Nothing like really good craftsmanship,” he says, laying the pieces out on the kitchen table. “Don’t make them like this any more. Keep going forever this will, when we’ve got it fixed.”

He’s right, doing this is comforting. It’s something I’ve done a thousand times before, while listening to the football on the radio with Granddad or talking to the family, or outside on the balcony in the summer.

“Feeling better, sweetheart?” he says after a couple of minutes. He’s peering at an ancient manual over his wonky reading glasses.

“It was scary, Granddad.”

“I’m sure it was, love. But, you’ve done the right thing, calling the police.”

The twins run through the kitchen, scattering Lego across the floor. They crash into the table, giggling, and run back the other way.

“Get out of it, you two,” says Mum, driving them into the lounge.

I glance at the old electric clock on the wall. Fifteen minutes since I rang.

“What’s going on?” asks Dad, struggling through the door with a stack of pizza boxes. “Why are you all looking so worried?”

* * *

It takes the police forty-four minutes. Two men in uniform arrive, take off their hats, sag on to chairs and clutch gratefully at Granddad’s treacly cups of tea. They both look like people who have been on duty since early morning and would like to go home. But they do take me seriously.

“I saw a man pull a gun on a woman in the middle of town, with like, loads of shoppers all around them,” I blurt. “From the bus.”

The policemen look surprised and I make myself breathe slowly. I’ve obviously said too much too quickly but Zahra chooses that moment to pour a load of popping corn into a pan full of hot oil and the little explosions that follow fill the empty space, giving the policemen a chance to catch up and me a chance to be ordinary.

I stuff my hands under my armpits to stop them from shaking, and stretch a smile over my face.

“So, Maya, first things first – who was on the bus – you or him? And which bus?” says the tall one, looking at the bike-engine parts spread all over the table.

“I was on the 139, in Regent Street.”

He fumbles for a pen and starts writing.

“And … what, in your own words, did you see?” he asks, his eyes flick from the paper to the box of motorbike parts.

I run through it all again. “A tall man, holding a gun, pointing it at a woman, on the street. Regent Street, at more or less exactly five fourteen. I took a photo, it’s on my phone.”

“Can we see?” says the short one.

“Yes – it’s just here,” I peer round the boxes and Granddad moves them to look underneath.

“I saw it earlier,” he says.

“Is that an old Ducati?” The policeman asks Dad, who’s sorting through the pizza boxes in case the phone’s got caught inside.

Dad blinks at the question. “The bike? No idea,” he says. “Ask her,” he points to me.

“No,” I say. “It’s a Vincent.”

Moving the fruit bowl and some cereal packets, I check the worktop, while Mum scans the dresser and Zahra stops making popcorn to look on the floor under the cupboards. The policemen stand and examine the chairs and stare at the clock, as if the phone might materialise there.

“It was here a moment ago – I showed the pictures to Mum,” I say, feeling desperate and stupid. “It can’t be that difficult to find. It’s got this pink cracked case.” I don’t tell them that the case falls off all the time and that all the pieces inside go flying all over the place.

“Have another look under this lot,” says Granddad and the policemen join in, picking through the boxes and scrabbling on the floor.

“It’ll be the twins,” says Mum, sighing. “Ishan!” she shouts down the corridor. “Precious!”

The twins waddle into the kitchen. “Have you seen my phone?” I ask.

Precious shakes her head and looks at the floor. Ishan swings from foot to foot, looks at me sideways before he runs out of the room and Mum follows.

“NO!” I hear her shout and race to see what she’s found.

The pink case is in the bathroom doorway. The battery’s lying on the bath mat, the phone too. The screen’s cracked but the first thing I really notice is the memory card.

“It’s gone,” I say. “The memory card’s gone.”

The short policeman appears behind me. “Is that important?”

I nod, blinking back tears and glaring at the twins, who yelp and run away. “Yes, I changed the settings so all the pictures get saved to the card.”

“Stick it all back in the phone anyway,” says Mum, already on her hands and knees, peering down the cracks in the floorboards. “Just in case…”

“I’ll talk to the twins,” says Zahra. “See if they can tell me what they did with it.”

“Let me see if anything’s been reported, although I think we’d know by now,” says the tall policeman, thumping back towards the kitchen, pressing the buttons on his phone as he goes.

He says something muffled and then I hear him say: “Five fourteen … Regent Street … just verify will you?”

I sniff back a tear and struggle to get the battery working in the phone. Slowly it switches on, pinging and swirling into life, and tells me that there’s no memory card. I press the gallery icon and there are no pictures.

“Sorry,” I say. “Nothing…”

The tall policeman smiles. He looks very tired. “Never mind. While your memory’s fresh, tell us what you saw. Tell us who you saw.”

They put down their mugs, pick up their pens, and write…

Chapter 4

When they’ve gone, we watch a Spider-Man film on the telly. All of us together. I sit between Mum and Dad, and Granddad snoozes in the corner. Rain taps on the windows, and I get up every now and again to check the street below. It’s empty.

The twins graze, passing through, grabbing handfuls of Zahra’s popcorn, before scuttling off to fight over the Lego.

Mum keeps jumping up to search in places where the twins might have hidden the memory card, but it’s so small, we’ll never find it.

I don’t really watch the film. No one in the family’s said anything, but I know we’re all feeling unsettled.

Zahra goes to bed. I go to bed.

I hear Mum and Dad locking up, Granddad coughing his way up to the attic.

I pull back the bedroom curtain and look out on to the street again. Two figures stand in the shadows under the bridge. Is that unusual?

A shiver goes down my spine.

“Zahra?” I whisper. “You still awake?”

“Yes,” she says.

“Can we share?”

“Yes.” And I clamber out of my bed and snuggle in alongside her. She feels much warmer than I do. We fold into each other, me behind, her in front, which means that I have a warm chest and she has a warm bum. She holds her funny old rabbit, the one Dad bought on the day she was born, so he’s warmest of all.

“How are you?” she asks.

“OK,” I lie.

“You’re not, are you?”

I lie there, feeling her warmth. It’s like cuddling a huge teddy bear. I don’t answer for a long time. I think about what I saw: a gun, a woman frightened and angry. The red-haired man. The camera flash. Them looking back at me. “If you want to know, I’m scared.”

“You don’t need to be. You saw him but why would he have seen you?”

“The camera flash. They looked up. He looked right at me.”

“Oh!” she says, pulling me tighter.

We lie there listening to the trains thundering over the railway bridge, the endless helicopters circling overhead.

“Can I sing you our song?” she says, eventually. “For the Christmas concert?”

* * *

I go through school the next day feeling jangly, but everything’s really normal. We’re doing Romeo and Juliet and we’ve just got to the death bit. Half the class is in tears, the rest are balancing pencils on their noses.

“So when Romeo sees Juliet, apparently dead—”

A cascade of pencils hits the floor.

Mr Nankivell pauses, and sighs. “What is it, Nathan?”

“What time are we doing the Secret Santa – Sir? Only I’ve got football practice and I don’t want to be late.”

“Just – let me get to the end – so Romeo says: ‘O true apothecary! Thy drugs are quick. Thus with a kiss I die’, priming the audience for…” Mr Nankivell stops and stares at Nathan who has slung his bag over his back and is trying to sneak out of the classroom unseen.

There’s a pause. Nathan freezes. We all stare.

Mr Nankivell sighs. “I give up,” he says, and thirty chairs scrape across the floor. The entire classroom stampedes past him and I see that Zahra’s making signs at me from the doorway. As I half stand to wave at her, the bell rings.

“So what do you think?” she asks me, waving toxic purple fingernails under my nose.

“Great,” I say. “Brilliant, are those allowed?”

She ignores that. “And I’ve found sick yellow tights online. You know, that half shade between green and yellow, almost lime – and the shoes, you should see the shoes, Maya – well, you will see the shoes, they’re so cute.”

“Good,” I say.

“You don’t care, do you?” she says. “You’re still thinking about last night, aren’t you?”

“What if he killed her?” I say, and she hugs me.

* * *

Later, I walk back home with her and together we veer on to the South Bank. We’re quickly caught in the bustle of people coming and going along the river, and like them, stop to stare at the coloured lights of the bridges and the Tate Modern warming up the freezing London dusk. A few leaves crunch under the thousands of feet and the smell of roasting nuts catches in my throat. The near horizon is a perfect pale green pierced by a single star, and the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral shows as a lit silhouette against it.

“God, London’s beautiful,” says Zahra.

“Yes,” I say. My mind is miles away, playing and replaying the scene from yesterday, all the way up to the police visit. The pictureless police visit.

“When we get home I’m going to search the twins’ room,” I say.

“Again?” she says.

Throwing our school bags to the ground we sit on a bench by the Globe and watch a small crowd form against the river railings. They’re pointing at something below them, but I don’t care, I’m too unsettled.

A man with a briefcase sits next to me and pulls out a newspaper.

Zahra and I watch a police boat buzzing up the river towards us.

The police boat is joined by another police boat. They’re still racing in our direction.

A toddler lets go of a balloon and howls as it takes off into the indigo sky. Her mother laughs and drags her off along the pavement.

The man leans forward to tie his shoelace.

A siren goes off behind us and an ambulance pulls around on to the cobbles in front of the Globe, closely followed by a police car. We stay on our bench and watch the ambulance crew and the policemen struggle over the railings and disappear.

“This looks too interesting – I’ve got to take a look,” says Zahra.

Reluctantly, I leave the bench and follow her to the railings. The two police boats are tied up at the jetty. Below us, on the little beach, there are several people standing in a ring around something on the sand. There’s a man in a white cover-all suit, several policemen and a paramedic. They’re all staring down.

“’S’a body,” says Zahra.

I peer at the darkened shore. People with reflective strips on their clothes catch the light from mobile phone cameras and police torches.

“My husband spotted it,” says a woman with pride.

“Yes,” says her husband. “I did.”

I tilt my head and realise that the thing I thought was seaweed is actually a pair of shoes. I trace my way up the body, slowly, just in case I see something horrible, but I can’t see the head, until one of the policemen gets out of the way.

The beam of a torch flashes across the hair. Ginger. Ginger curls.

“Oh my God!” I mutter. “It’s him. The man I saw from the bus.”

Chapter 5

But it isn’t.

“Have a cup of tea,” says Granddad. “How was school?”

I know he’s trying to change the subject.

“I’m still not convinced it wasn’t him,” says Zahra, as she reaches into the bread bin with one hand and the fridge with the other.

“It wasn’t,” I say. “Definitely not.”

“People look different when they’re dead,” says Granddad.

“Not that different,” I say. “Wrong-shaped face, wrong nose. The man on the beach was skinny. The man on the street was solid.” My voice sounds cheery and matter-of-fact, but I don’t really feel like that inside. I’ve never seen a dead body before. It was weird. Waxy.

“Just a coincidence, then,” says Zahra. “You know, two red-headed men in a city of eight million.”