Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: libreka classics

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

libreka classics – These are classics of literary history, reissued and made available to a wide audience. Immerse yourself in well-known and popular titles!

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 164

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Titel: My Summer in a Garden

von ca. 337-422 Faxian, Sir Samuel White Baker, Sax Rohmer, Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, Maria Edgeworth, Saint Sir Thomas More, Herodotus, L. Mühlbach, Herbert Allen Giles, G. K. Chesterton, Algernon Charles Swinburne, Rudyard Kipling, A. J. O'Reilly, William Bray, O. Henry, graf Leo Tolstoy, Anonymous, Lewis Wallace, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Edgar Allan Poe, Jack London, Elizabeth Cleghorn Gaskell, Jules Verne, Frank Frankfort Moore, Susan Fenimore Cooper, Anthony Trollope, Henry James, T. Smollett, Thomas Burke, Emma Goldman, George Eliot, Henry Rider Haggard, Baron Thomas Babington Macaulay Macaulay, A. Maynard Barbour, Edmund Burke, Gerold K. Rohner, Bernard Shaw, Sir Joshua Reynolds, Bret Harte, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Jerome K. Jerome, Isabella L. Bird, Christoph Martin Wieland, Rainer Maria Rilke, Ludwig Anzengruber, Freiherr von Ludwig Achim Arnim, G. Harvey Ralphson, John Galsworthy, George Sand, Pierre Loti, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Giambattista Basile, Homer, John Webster, P. G. Wodehouse, William Shakespeare, Edward Payson Roe, Sir Walter Raleigh, Victor [pseud.] Appleton, Arnold Bennett, James Fenimore Cooper, James Hogg, Richard Harding Davis, Ernest Thompson Seton, William MacLeod Raine, E. Phillips Oppenheim, Maksim Gorky, Henrik Ibsen, George MacDonald, Sir Max Beerbohm, Lucy Larcom, Various, Sir Robert S. Ball, Charles Darwin, Charles Reade, Adelaide Anne Procter, Joseph Conrad, Joel Chandler Harris, Joseph Crosby Lincoln, Alexander Whyte, Kate Douglas Smith Wiggin, James Lane Allen, Richard Jefferies, Honoré de Balzac, Wilhelm Busch, General Robert Edward Lee, Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, David Cory, Booth Tarkington, George Rawlinson, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Dinah Maria Mulock Craik, Christopher Evans, Thomas Henry Huxley, Mary Roberts Rinehart, Erskine Childers, Alice Freeman Palmer, Florence Converse, William Congreve, Stephen Crane, Madame de La Fayette, United States. Army. Corps of Engineers. Manhattan District, Willa Sibert Cather, Anna Katharine Green, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Charlotte M. Brame, Alphonse Daudet, Booker T. Washington, Clemens Brentano, Sylvester Mowry, Geoffrey Chaucer, Ellen Anderson Gholson Glasgow, Gail Hamilton, William Roscoe Thayer, Margaret Wade Campbell Deland, Rafael Sabatini, Archibald Henderson, Albert Payson Terhune, George Wharton James, Padraic Colum, James MacCaffrey, John Albert Macy, Annie Sullivan, Helen Keller, Walter Pater, Sir Richard Francis Burton, Baron de Jean-Baptiste-Antoine-Marcelin Marbot, Aristotle, Gustave Flaubert, 12th cent. de Troyes Chrétien, Valentine Williams, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Alexandre Dumas fils, John Gay, Andrew Lang, Hester Lynch Piozzi, Jeffery Farnol, Alexander Pope, George Henry Borrow, Mark Twain, Francis Bacon, Margaret Pollock Sherwood, Henry Walter Bates, Thornton W. Burgess, Edmund G. Ross, William Alexander Linn, Voltaire, Giles Lytton Strachey, Henry Ossian Flipper, Émile Gaboriau, Arthur B. Reeve, Hugh Latimer, Baron Edward Bulwer Lytton Lytton, Benito Pérez Galdós, Robert Smythe Hichens, Niccolò Machiavelli, Prosper Mérimée, Ivan Sergeevich Turgenev, Anatole Cerfberr, Jules François Christophe, Victor Cherbuliez, Edgar B. P. Darlington, David Grayson, Mihai Nadin, Helen Beecher Long, Plutarch, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Margaret E. Sangster, Herman Melville, John Keats, Fannie Isabel Sherrick, Maurice Baring, William Terence Kane, Mary Russell Mitford, Henry Drummond, Rabindranath Tagore, Hubert Howe Bancroft, Charlotte Mary Yonge, William Dean Howells, Jesse F. Bone, Basil Hall Chamberlain, William Makepeace Thackeray, Samuel Butler, Frances Hodgson Burnett, E. Prentiss, Sir Walter Scott, Alexander K. McClure, David Livingstone, Bram Stoker, Victor Hugo, Patañjali, Amelia Ruth Gere Mason, Bertrand Russell, Alfred Russel Wallace, Molière, Robert Louis Stevenson, Simona Sumanaru, Michael Hart, Edmund Gosse, Samuel Smiles, Pierre Corneille, Clarence Edward Mulford, Mrs. Oliphant, George Pope Morris, Aristophanes, baron de Etienne-Léon Lamothe-Langon, William Morris, Henry David Thoreau, E. C. Bentley, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Hippolyte Taine, Pedro Calderón de la Barca, John Philip Sousa, Wilhelm Grimm, Jacob Grimm, William Gardner, J. M. Judy, E. M. Forster, Percival Lowell, Alexandre Dumas père, William Greenwood, John Dryden, William T. Sherman, John Kendrick Bangs, Burton Egbert Stevenson, Eugene Wood, John Arbuthnot, Sir Richard Steele, Sir George Otto Trevelyan, William Charles Henry Wood, Marcel Proust, Philip Henry Sheridan, Abraham Lincoln, John Pinkerton, Thomas Hardy, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Oliver Goldsmith, Freiherr von der Friedrich Trenck, Eugene Field, Charles Dudley Warner, Andrew Everett Durham, Emily Dickinson, Emperor of Rome Marcus Aurelius, Edgar Wallace, Annie Roe Carr, Eleanor Stackhouse Atkinson, George McKinnon Wrong, Heinrich Zschokke, Harold Howland, Grace S. Richmond, Louisa May Alcott, Thomas Edwards, William Kirby, John McElroy, Margaret Sidney, Ford Madox Ford, Clara Louise Burnham, Karl Friedrich May, Friedrich Schiller, Baroness Emmuska Orczy Orczy, Margaret Penrose, Joseph Addison, Silvio Pellico, Alfred Ollivant, Irving Bacheller, James Harrington, Helen Hunt Jackson, Abraham Cahan, G. A. Henty, Mary Johnston, Marcus Tullius Cicero, Hamlin Garland, George Washington Plunkitt, the Younger Pliny, James Joyce, Henry Adams, Tommaso Campanella, Marshall Saunders, Don Manoel Gonzales, Friedrich Heinrich Karl Freiherr de La Motte-Fouqué, Saki, Oscar Douglas Skelton, Nathaniel W. Stephenson, João Simões Lopes Neto, Heinrich Heine, Flavius Josephus, Henryk Sienkiewicz, Melville Davisson Post, Howard Pyle, William Harrison Ainsworth, Fergus Hume, John Lydgate, Robert Browning, Louis Ginzberg, Carolyn Wells, Jean-Henri Fabre, Christian Friedrich Hebbel, Frederic William Moorman, Hugo Ball, James Stephens, Khristo Botev, Franklin Hichborn, Walter Lynwood Fleming, Solon J. Buck, Holland Thompson, Johan Bojer, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Sidonia Hedwig Zäunemann, Octave Thanet, May Agnes Fleming, Giacomo Casanova, Albert Bigelow Paine, W. B. M. Ferguson, Edward Carpenter, Francis Pretty, Henry Festing Jones, Cornelius Tacitus, Neltje Blanchan, Allen Johnson, Willis George Emerson, A. R. Narayanan, John Bursey, Frederic Austin Ogg, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Dorothy Miller Richardson, William Hazlitt, Robert Frost, John Fox, Lucretia P. Hale, Max Farrand, Emerson Hough, Jesse Macy, John Moody, Burton Jesse Hendrick, Samuel Peter Orth, James Elroy Flecker, Henry Jones Ford, William R. Shepherd, Sydney George Fisher, Will N. Harben, Theodor Mommsen, Ellsworth Huntington, Constance Lindsay Skinner, Walter De la Mare, John Reed, Guy de Maupassant, Carl Lotus Becker, Archer Butler Hulbert, Ralph Delahaye Paine, James Legge

ISBN 978-3-7429-3026-2

Alle Rechte vorbehalten.

Es ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Erlaubnis nicht gestattet, dieses Werk im Ganzen oder in Teilen zu vervielfältigen oder zu veröffentlichen.

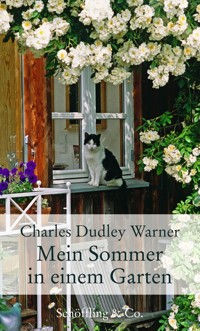

SUMMER IN A GARDEN

and

CALVIN,

A STUDY OF CHARACTER

By Charles Dudley Warner

Contents

INTRODUCTORY LETTER

BY WAY OF DEDICATION

PRELIMINARY

FIRST WEEK

SECOND WEEK

THIRD WEEK

FOURTH WEEK

FIFTH WEEK

SIXTH WEEK

SEVENTH WEEK

EIGHTH WEEK

NINTH WEEK

TENTH WEEK

ELEVENTH WEEK

TWELFTH WEEK

THIRTEENTH WEEK

FOURTEENTH WEEK

FIFTEENTH WEEK

SIXTEENTH WEEK

SEVENTEENTH WEEK

EIGHTEENTH WEEK

NINETEENTH WEEK

CALVIN

INTRODUCTORY LETTER

MY DEAR MR. FIELDS,—I did promise to write an Introduction to these charming papers but an Introduction,—what is it?—a sort of pilaster, put upon the face of a building for looks' sake, and usually flat,—very flat. Sometimes it may be called a caryatid, which is, as I understand it, a cruel device of architecture, representing a man or a woman, obliged to hold up upon his or her head or shoulders a structure which they did not build, and which could stand just as well without as with them. But an Introduction is more apt to be a pillar, such as one may see in Baalbec, standing up in the air all alone, with nothing on it, and with nothing for it to do.

But an Introductory Letter is different. There is in that no formality, no assumption of function, no awkward propriety or dignity to be sustained. A letter at the opening of a book may be only a footpath, leading the curious to a favorable point of observation, and then leaving them to wander as they will.

Sluggards have been sent to the ant for wisdom; but writers might better be sent to the spider, not because he works all night, and watches all day, but because he works unconsciously. He dare not even bring his work before his own eyes, but keeps it behind him, as if too much knowledge of what one is doing would spoil the delicacy and modesty of one's work.

Almost all graceful and fanciful work is born like a dream, that comes noiselessly, and tarries silently, and goes as a bubble bursts. And yet somewhere work must come in,—real, well-considered work.

Inness (the best American painter of Nature in her moods of real human feeling) once said, "No man can do anything in art, unless he has intuitions; but, between whiles, one must work hard in collecting the materials out of which intuitions are made." The truth could not be hit off better. Knowledge is the soil, and intuitions are the flowers which grow up out of it. The soil must be well enriched and worked.

It is very plain, or will be to those who read these papers, now gathered up into this book, as into a chariot for a race, that the author has long employed his eyes, his ears, and his understanding, in observing and considering the facts of Nature, and in weaving curious analogies. Being an editor of one of the oldest daily news-papers in New England, and obliged to fill its columns day after day (as the village mill is obliged to render every day so many sacks of flour or of meal to its hungry customers), it naturally occurred to him, "Why not write something which I myself, as well as my readers, shall enjoy? The market gives them facts enough; politics, lies enough; art, affectations enough; criminal news, horrors enough; fashion, more than enough of vanity upon vanity, and vexation of purse. Why should they not have some of those wandering and joyous fancies which solace my hours?"

The suggestion ripened into execution. Men and women read, and wanted more. These garden letters began to blossom every week; and many hands were glad to gather pleasure from them. A sign it was of wisdom. In our feverish days it is a sign of health or of convalescence that men love gentle pleasure, and enjoyments that do not rush or roar, but distill as the dew.

The love of rural life, the habit of finding enjoyment in familiar things, that susceptibility to Nature which keeps the nerve gently thrilled in her homliest nooks and by her commonest sounds, is worth a thousand fortunes of money, or its equivalents.

Every book which interprets the secret lore of fields and gardens, every essay that brings men nearer to the understanding of the mysteries which every tree whispers, every brook murmurs, every weed, even, hints, is a contribution to the wealth and the happiness of our kind. And if the lines of the writer shall be traced in quaint characters, and be filled with a grave humor, or break out at times into merriment, all this will be no presumption against their wisdom or his goodness. Is the oak less strong and tough because the mosses and weather-stains stick in all manner of grotesque sketches along its bark? Now, truly, one may not learn from this little book either divinity or horticulture; but if he gets a pure happiness, and a tendency to repeat the happiness from the simple stores of Nature, he will gain from our friend's garden what Adam lost in his, and what neither philosophy nor divinity has always been able to restore.

Wherefore, thanking you for listening to a former letter, which begged you to consider whether these curious and ingenious papers, that go winding about like a half-trodden path between the garden and the field, might not be given in book-form to your million readers, I remain, yours to command in everything but the writing of an Introduction,

BY WAY OF DEDICATION

MY DEAR POLLY,—When a few of these papers had appeared in "The Courant," I was encouraged to continue them by hearing that they had at least one reader who read them with the serious mind from which alone profit is to be expected. It was a maiden lady, who, I am sure, was no more to blame for her singleness than for her age; and she looked to these honest sketches of experience for that aid which the professional agricultural papers could not give in the management of the little bit of garden which she called her own. She may have been my only disciple; and I confess that the thought of her yielding a simple faith to what a gainsaying world may have regarded with levity has contributed much to give an increased practical turn to my reports of what I know about gardening. The thought that I had misled a lady, whose age is not her only singularity, who looked to me for advice which should be not at all the fanciful product of the Garden of Gull, would give me great pain. I trust that her autumn is a peaceful one, and undisturbed by either the humorous or the satirical side of Nature.

You know that this attempt to tell the truth about one of the most fascinating occupations in the world has not been without its dangers. I have received anonymous letters. Some of them were murderously spelled; others were missives in such elegant phrase and dress, that danger was only to be apprehended in them by one skilled in the mysteries of medieval poisoning, when death flew on the wings of a perfume. One lady, whose entreaty that I should pause had something of command in it, wrote that my strictures on "pusley" had so inflamed her husband's zeal, that, in her absence in the country, he had rooted up all her beds of portulaca (a sort of cousin of the fat weed), and utterly cast it out. It is, however, to be expected, that retributive justice would visit the innocent as well as the guilty of an offending family. This is only another proof of the wide sweep of moral forces. I suppose that it is as necessary in the vegetable world as it is elsewhere to avoid the appearance of evil.

In offering you the fruit of my garden, which has been gathered from week to week, without much reference to the progress of the crops or the drought, I desire to acknowledge an influence which has lent half the charm to my labor. If I were in a court of justice, or injustice, under oath, I should not like to say, that, either in the wooing days of spring, or under the suns of the summer solstice, you had been, either with hoe, rake, or miniature spade, of the least use in the garden; but your suggestions have been invaluable, and, whenever used, have been paid for. Your horticultural inquiries have been of a nature to astonish the vegetable world, if it listened, and were a constant inspiration to research. There was almost nothing that you did not wish to know; and this, added to what I wished to know, made a boundless field for discovery. What might have become of the garden, if your advice had been followed, a good Providence only knows; but I never worked there without a consciousness that you might at any moment come down the walk, under the grape-arbor, bestowing glances of approval, that were none the worse for not being critical; exercising a sort of superintendence that elevated gardening into a fine art; expressing a wonder that was as complimentary to me as it was to Nature; bringing an atmosphere which made the garden a region of romance, the soil of which was set apart for fruits native to climes unseen. It was this bright presence that filled the garden, as it did the summer, with light, and now leaves upon it that tender play of color and bloom which is called among the Alps the after-glow.

NOOK FARM, HARTFORD, October, 1870

PRELIMINARY

The love of dirt is among the earliest of passions, as it is the latest. Mud-pies gratify one of our first and best instincts. So long as we are dirty, we are pure. Fondness for the ground comes back to a man after he has run the round of pleasure and business, eaten dirt, and sown wild-oats, drifted about the world, and taken the wind of all its moods. The love of digging in the ground (or of looking on while he pays another to dig) is as sure to come back to him as he is sure, at last, to go under the ground, and stay there. To own a bit of ground, to scratch it with a hoe, to plant seeds and watch, their renewal of life, this is the commonest delight of the race, the most satisfactory thing a man can do. When Cicero writes of the pleasures of old age, that of agriculture is chief among them:

"Venio nunc ad voluptates agricolarum, quibus ego incredibiliter delector: quae nec ulla impediuntur senectute, et mihi ad sapientis vitam proxime videntur accedere." (I am driven to Latin because New York editors have exhausted the English language in the praising of spring, and especially of the month of May.)

Let us celebrate the soil. Most men toil that they may own a piece of it; they measure their success in life by their ability to buy it. It is alike the passion of the parvenu and the pride of the aristocrat. Broad acres are a patent of nobility; and no man but feels more, of a man in the world if he have a bit of ground that he can call his own. However small it is on the surface, it is four thousand miles deep; and that is a very handsome property. And there is a great pleasure in working in the soil, apart from the ownership of it. The man who has planted a garden feels that he has done something for the good of the World. He belongs to the producers. It is a pleasure to eat of the fruit of one's toil, if it be nothing more than a head of lettuce or an ear of corn. One cultivates a lawn even with great satisfaction; for there is nothing more beautiful than grass and turf in our latitude. The tropics may have their delights, but they have not turf: and the world without turf is a dreary desert. The original Garden of Eden could not have had such turf as one sees in England. The Teutonic races all love turf: they emigrate in the line of its growth.

To dig in the mellow soil-to dig moderately, for all pleasure should be taken sparingly—is a great thing. One gets strength out of the ground as often as one really touches it with a hoe. Antaeus (this is a classical article) was no doubt an agriculturist; and such a prize-fighter as Hercules could n't do anything with him till he got him to lay down his spade, and quit the soil. It is not simply beets and potatoes and corn and string-beans that one raises in his well-hoed garden: it is the average of human life. There is life in the ground; it goes into the seeds; and it also, when it is stirred up, goes into the man who stirs it. The hot sun on his back as he bends to his shovel and hoe, or contemplatively rakes the warm and fragrant loam, is better than much medicine. The buds are coming out on the bushes round about; the blossoms of the fruit trees begin to show; the blood is running up the grapevines in streams; you can smell the Wild flowers on the near bank; and the birds are flying and glancing and singing everywhere. To the open kitchen door comes the busy housewife to shake a white something, and stands a moment to look, quite transfixed by the delightful sights and sounds. Hoeing in the garden on a bright, soft May day, when you are not obliged to, is nearly equal to the delight of going trouting.