2,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

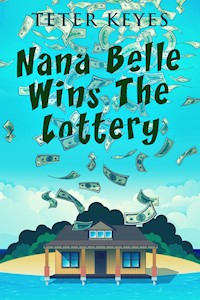

10-year-old Henry Rowley's family life is about to change, big time. After his grandmother Belle McNally wins $109 million in a lottery, she decides to use the money to bring her estranged daughters together and mend their relationship.

But soon after arrival, Belle passes away and rest are left to fend for themselves. The sisters, Rita, Mary Beth and Jennifer, couldn't be different from each other, and to make things worse, Belle's will states that the three have to stay together in the same place for thirty days, or be disinherited.

With the stakes high and no TV, internet or cell phone service, tensions soon rise. But will the sisters be able to overcome their differences, and who will inherit the money?

Told from young Henry's perspective, 'Nana Belle Wins The Lottery' is a hilarious, warm-hearted family comedy for readers of all ages.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

NANA BELLE WINS THE LOTTERY

TETER KEYES

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

About the Author

Copyright (C) 2022 Teter Keyes

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2022 by Next Chapter

Published 2022 by Next Chapter

Edited by Graham (Fading Street Services)

Cover art by CoverMint

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author's permission.

To my brothers Dave and Jim, and my grandsons, Zachary and Roy III. Over the years, they have allowed me to observe the fascinating workings inside the brains of ten- and eleven-year-old boys. Love you guys.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many thanks to my writer friends. Your input helped me shape the work and smooth the rough spots. As always, thank you to my daughters, Cher and Chasta, and my grandchildren for supporting my writing habit. Thank you to Joe, chief driver on our research trip to the Carolinas.

CHAPTERONE

Mom is pinching the skin between her eyebrows. It’s a totally familiar thing. What normally follows is, “Henry, to your room. Now.” When that happens, I claim innocence, but I usually know the reason she’s angry. This time I am innocent and whoever is on the other end of their phone conversation is the one in deep doo-doo.

“Are you sure?” she is saying. Pinch, pinch. “Calm down. Just tell me what happened.”

The caller is one of my grandmothers. I know this because she said, “Hi, Mom,” when she answered. What I don’t know is whether it is Nana Belle, her mother, or Grandma Grace, Dad’s mom.

“What, what?” I ask her, bouncing on my toes.

Mom waves me away and turns her back to me, listening. Pond scum, I’m ten years old and still being treated like a baby.

“Okay, okay,” Mom is saying. “Did you talk to anyone about this yet?”

Silently, she listens.

“No, I don’t mean Rita and Mary Beth. I mean someone at their office. At least talk to a lawyer before you–” She stops talking, listens again.

Rita and Mary Beth are my aunts, Mom’s sisters, so I now know it must be Nana Belle on the phone.

Bounce, bounce.

Mom turns back around and points at my feet. I try to stop bouncing. It’s hard.

My grandpa, John McNally, died before I was born, and Mom asked Nana if she has already talked to my aunts, so that means no one has died. That leaves someone is sick, there’s been a fire, or a sinkhole opened up under Nana Belle’s old Nebraska house. Dad says I have a calculating mind. He claims credit for that since he writes complicated software and says it requires serious machinations. Mom says I’m just a Curious George, like in the book she used to read to me, and that all my curiosity will get me in trouble one day, just like George.

I’d like to watch a big sinkhole swallow a house. Not with Nana Belle inside, of course. I picture a deep, round hole gobbling up Nana’s home. I imagine the panicked squeal of her squeaky screen door as the old porch is sucked down.

Mom pushes the button to end the call and drops onto a chair. She pulls her hair back with both hands like she’s trying to keep the top of her head from popping off.

“What, what?” I ask again, bouncing on my feet.

“I gotta call your dad,” she says and stands up.

“Mom!” I shout. “Did Nana Belle’s house fall into a sinkhole?”

“A what?”

Oops, imagination overflow.

She looks at me, puzzled. I take a big breath and ask as calmly as I can, “What did Nana say?”

She put her hands on my shoulders. Her eyes are all shiny. “Henry, your nana just won the lottery.”

My turn to ask, “What?”

“The Powerball. The big one. Nana won it.” She twirls around the room, singing, “Momma won it. One hundred and nine million smackers. She won, she won. One hundred and nine million. I can’t believe it.”

She stops mid-twirl and puts a hand over her mouth. Around it, she says, “I gotta call your dad.” Then she picks up her phone and goes outside.

The lottery? This is better than watching Nana’s house flush down a hole.

I didn’t think all the twirling was just happiness for my nana. I’m guessing Mom believes some of that money will come to her and my aunties.

And aren’t I the only child of loving parents? Snap, I am. Visions of new gaming systems and the upcoming new video game I saw on TV dance in my head.

The next two days are busy. Mom acts all weird. She made a jillion, million calls to my nana and aunties. She takes my old clothes out of drawers and closets, the ones I already grew out of, but then she gets all distracted and the piles sit on my floor for a couple of days. Once she was fixing supper, and the chicken almost burned because she kept on staring out the window. She and Dad have conversations in their room with the door shut. Hello, did you forget you had a kid?

“Mom?” I keep asking, but she just pats me on the back and says things will all work out. Zombieville.

Mom gets tickets so we can fly out to visit Nana Belle. I want Dad to come with us. Mom does too, but he tells Mom he loves her, but there was no way he is going to spend time with her family.

They talk in whispers in the kitchen while I’m a room away with my earphones on. I don’t have music playing, but they don’t know that. Curious George I am, but how else can I know what’s going on? Dad says “dysfunctional” in a loud whisper. I peek around the edge of my door and see Mom turning to him with the knife she had been using to chop tomatoes and she asks him if he wants to say that again. Apparently, Dad does not because he leaves.

“What’re you listening to, Henry?” he asks when he walks past and pats my head.

“Just some music,” I tell him. “Why don’t you want to come with us?”

We had gone to Nebraska where Nana Belle lives two Christmases ago. What I remember is that everything was brown and dead-looking, and when I stood outside all I saw was sky in every direction. That is if anyone wanted to stay outside long enough in the cold and wind. It’s totally different from Seattle where we live. I’m not even mentioning having to see my bratty girl cousins. No, I’m not looking forward to Nebraska.

“Mom,” I ask over dinner, “Why can’t I stay with Dad, and you go? It’s cold at Nana’s and Heather’s a brat.”

“Don’t call Heather a brat,” Mom said. “Plus, it’s summer now.”

Then what she says changes everything. “We’re not going to Nebraska, anyway, honey. Nana rented a beach cottage on one of the islands off the South Carolina coast.”

“Island? You mean with an ocean and boats and swimming and everything?” This is good news.

“That’s right.” Mom beams me a smile. “It’s on the Atlantic Ocean, not the Pacific like Seattle. There’ll be sandy beaches, and you can swim. But, young man,” she continues, pointing a fork at me, “you will not swim without an adult present.”

“Will Heather and Sarah Beth be there?”

“I think it’s just going to be us, your aunts, and Nana, at least for now.”

This is even better news.

She looks at me for a long time as if seeing how much I have grown. I straighten in the chair to make myself look taller. Then she tells my dad, “I hate to admit it, but you’re right, my family is not a normal, healthy one.”

Dad snorts.

“Things were, I’d guess you could say, difficult growing up, especially for Rita and Mary Beth. They’re older than me. My dad, your Grandpa John, had problems.”

“He was a drunk,” Dad says.

“Hush, Peter. My dad was in the war, and he didn’t come back the same. Now, he would have been diagnosed with PTSD, that’s post-traumatic stress disorder,” she explains to me. “Back then it was different; people didn’t understand the condition. Plus, the vets coming back were criticized, some were even spat on.”

She points a fork at my dad.

What is it with her today with the sharp stuff?

“He was still a successful man. He operated his pharmacy and provided for Mom and us. It’s just that—”

“He drank,” Dad says. “To excess. Often.”

“Hello, I was there. I know he did, and it made home life difficult. Especially when my mother was—”

“An enabler,” finishes my dad.

“Well, he had cut back a lot by the time I was in junior high. Life was easier then.”

“Because he had cirrhosis of the liver. Not that it stopped him.”

“Enough!”

“Anyway,” she goes on, looking at me, “Your Nana Belle wants to get us girls together for a couple of weeks, see if we can talk things over, and find a way to come closer. We all suffered as kids, then we scattered across the country, and no one discussed it. Now with the money, there’s an opportunity to get together, talk, and heal.”

CHAPTERTWO

Wednesday morning we get on a plane to South Carolina. Mom’s a teacher, and it’s July, so she’s free. Me, too.

We change planes in Denver. Mom’s already told me it will be a long flight and packed snacks. I’m making a list of things I want to buy in the notebook I always carry with me when I hear my mom sniffle. She pulls her purse out from under the seat, digs for a tissue, and wipes her eyes and nose.

“You okay, Mom?”

“Sure, honey, just thinking about things. The cabin air must be too dry.”

We’re quiet for a while. Me working on my list and Mom reading her Kindle.

“Mom?”

“Yes?”

I whisper, “You think Nana is going to give you some of the money she won?”

“Yes,” she whispers back. “She already told us she wants to give us a share.”

I lean in close. “Does that mean I get a bigger allowance?”

Mom laughs and hugs me. “We’ll see, young man. Don’t think I haven’t seen you working on your wish list.”

Finally, we land. While we wait for our luggage, Mom talks on the phone. I look around, but all I see are people talking on phones or waiting. The carousel finally jerks awake, and Mom clicks off the phone. She’s frowning.

“Is Nana Belle going to pick us up?” I ask.

“No. Apparently, Mary Beth is just too busy making dinner, and Nana isn’t feeling well.” She sighs then shakes her head. “Let’s look for a cab that will take us to the ferry. It sounds like that’s the only way to get to the island.” She says something under her breath that I can’t catch, picks up her suitcases, and we make our way to the door.

I do the same, except for the muttering.

A cab takes us to the harbor where we find the ferry. Last trip, the captain announces as we get on.

By the time we get off at the small dock on the island where Nana is staying, it’s starting to get dark.

I’m starving. We had eaten at McDonald’s when we switched planes in Denver and had snacks, but that seems like years ago. At least that’s what my growling stomach claims.

We walk up the lighted path to the beach house Nana rented. I wonder what Aunt Mary Beth cooked for supper. Is it fried chicken, or maybe grilled? We walk a few more steps up the slope. Is it hamburgers with gobs of ketchup and fluffy white buns that have been smashed on top of the burgers while they’re still in the pan? Yum.

Mom gives Nana a big hug.

“Mary Beth said you weren’t feeling well, Mom. Are you okay?”

“Yes, honey,” Nana tells my mom. “Just been tired is all with all the excitement and then the move here. Now you come here, young man, and give your nana a hug.”

I do, breathing in the nana scent of flowers and baking bread.

It’s Mary Beth’s turn next. She hugs Mom, but it is a quick hug and release. My auntie is even fatter than the last time I saw her, and I’m glad she didn’t swallow mom up in a bigger hug. She’s wearing a baggy dress, and I see crooked toes on her bare feet. I wouldn’t have noticed the toes except for the bright red toenail polish. She ruffles my hair but skips the hug. I sniff, still wondering about dinner.

“I wish you would have said something earlier,” Mary Beth says. “Mom and I had TV dinners since it was just the two of us.”

“Fried chicken,” Nana says. “Mary Beth had two and then finished mine.”

“Momma,” Mary Beth says. “You said you weren’t hungry. She pats her big belly. “I, on the other hand, was starving.”

“Sure,” Mom says, looking around. “Any of the frozen dinners left? We haven’t had anything to eat since the Denver airport. I’m sure Henry’s famished.”

I nod big time.

“You can look, Jennifer,” Nana says.

I sit down at the kitchen bar. Mom opens the freezer and rummages around.

“Rita will be here later,” Nana says.

“Not if she’s taking the ferry. We took the last one out for the day,” Mom says, still searching. She pulls out a package, looks at it, and puts it back. “Don’t you have anything other than fried chicken dinners?”

“I’m fine with that,” I chime in.

“Nothing wrong with fried chicken and spuds,” Mary Beth says. “Least it sticks to your ribs.”

“I can tell,” Mom says in that tone Dad and I know so well.

“Mom, chicken is fine with me,” I say for the second time.

“Girls, I’m not going to have any bickering,” Nana tells them. “I invited you all here, Rita too, because I want us to sit down and really talk with each other. God knows we had some difficult times when you were little.”

“Dad drank and we all suffered, you mean,” my mom says.

“Hush, don’t speak badly of the dead. I know your dad had problems, but he still did well for us. We always had a roof over our heads and food on the table. That’s better than some men I know. He worked hard and if he had a drink to relax, well—well, I just want us all to get along.”

My mom goes over and hugs Nana. “Sorry, Mom. I think it’s a great idea to get everyone together for a reunion. Thank you.”

Nana sniffs, pulls a tissue from her pocket, and wipes her eyes. “I just thank God that I was blessed with the winning lottery ticket.” She makes the sign of the cross—a touch to her forehead, stomach, left shoulder, right shoulder—then kisses her fingers and lifts them to the ceiling. I am surprised, considering I thought Nana was Methodist like us, but I don’t say anything.

“It came just in time,” she continues. “We’ve always owned the house, the one you girls grew up in, but I need to replace the roof. And the plumbing is bad. I haven’t used the bathroom upstairs forever since the pipe under the vanity rotted out. Got tired of having to empty the bucket whenever I ran water in the sink.”

“Mom, you should have said something. Peter and I would have paid to have a plumber come out and fix that.”

“You have enough going on in your life, with teaching school and taking care of Henry. I didn’t want to bother you.”

Everyone turns to stare at me.

Awkward.

“I’m thinking of selling the old house, anyway,” Nana continues. “I’m just rattling around in that big place, too much space. And the taxes and upkeep. That’s the expensive part.”

“But we all grew up in that home,” Mary Beth says all whiney. “Think of all the memories we have there.”

“So, you’re saying your terrible childhood wasn’t all that bad?” This from my mom in the sarcastic voice again. Two zingers in one day, a new record.

“How would you know anyway, Jennifer,” Mary Beth shoots back. “You being the baby and all, growing up after Dad started Alcoholics Anonymous.”

“Not that he ever took that seriously.”

“Stop it,” Nana says, slapping her hand on the countertop. “This is exactly what I was talking about. Bicker, bicker, that’s all this family has done for years. I’m tired of it.”

I keep my head down and go on eating the dinner Mom cooked in the microwave. This is interesting. Mom doesn’t talk about being a kid other than to say she couldn’t wait to go to college and get out of Nebraska. I pick up a chicken leg and chew on the bone. Mom watches, and then without me asking, pulls another dinner out of the freezer and puts it in the microwave. Mom’s good at reading minds.

“I’m gonna fix up the house and sell it,” Nana tells them. “Buy me a condo somewhere. A warm place on the beach, maybe. It’s beautiful here, and I’ve always wanted to live near the ocean. Winters are pleasant, everyone says.” She sighs, smiles. “I’m not going to miss snow at all.” The smile widens. “Think I’ll have enough money to get a little condo on the beach?”

Everyone laughs, and Nana grabs more hugs from us all.

The beach house Nana rented is big. In the great room are large windows and a sliding glass door that opens out to the beach. I step outside on the deck. There’s a full moon, and the light makes the waves look like they’re waving at the moon’s face. I can see that the deck wraps all the way around the side of the house. This is going to be fun. I breathe in the warm salt air and then go back inside, holding a hand over my yawn.

“You’re sleeping in the bedroom on that side,” Nana says, pointing to a door.

The kitchen is open to the great room, and, on both sides, I see other doors leading to what looks like a bunch more rooms.

“There’s a Jack and Jill bathroom between your room and the one on the other side.” Nana points to a door near mine. “Jennifer, you can sleep in the room on the other side of the bathroom, next to Henry.”

“I have the room closest to Mom,” Mary Beth says smugly, and motions to the opposite corner. “Mom has the master, of course. There’s a balcony off it, facing the sea.” She looks at me for a moment and then says, “Jen, if I knew you were bringing Henry here, I would have brought my girls. But,” she pauses, “I thought this was supposed to be a time for just Mom and us girls.”

Inside I groan but manage to clamp it before the groan pops out.

“Peter’s working on a big project,” Mom explains. “He’s been working ten to twelve hours a day.”

“And what does he do again that’s so all-fired important?” Mary Beth asks, one fist on a plump hip.

“Like I’ve explained to you before, Sis, his company writes software programs.”

She waves the hand not on her hip. “That seems to be, I don’t know, such a fuzzy science. At least my Stephen does something that we can visualize. He puts a ‘For Sale’ sign in front of a house, shows it to people, writes contracts, and then puts up a sold sign when the house sells. Real estate, that’s something you can see, touch, feel.”

“Touch and feel are the same,” I say.

“You know what I mean, Henry,” Mary Beth snaps. “Don’t get smart.”

Mom starts to say something back to her sister, but Nana Belle puts out a hand in a ‘stop’ gesture and gives a loud whistle. Go, Nana.

“This is exactly what I wanted to avoid,” she says. Then speaking slowly and deliberately, “We are all going to have a nice visit, and we are going to get along.”

Suddenly, I’m very tired. I grab a suitcase and go to my assigned room.

Five minutes later, I come back out.

“Nana, how do I connect with your Internet? You have a router set up?”

Nana looks puzzled for a moment then says, “No Internet out here, honey. And cell phones don’t work this far from the mainland. All we have is the landline. When it works, that is. That’s the number your mom called on earlier.”

“No Internet?” I can’t believe it. “I guess I’ll just watch TV.”

“No television reception either,” Nana is smiling. I’m feeling doom.

“Sorry, honey,” Nana went on. “That’s one of the reasons I selected this place. No distractions. There’s plenty to do. There are fishing poles in storage under the house. You can walk on the beach looking for shells, read, swim, snorkel. I think there are even a couple of bicycles around.”

I’m so doomed, I think as I slump back to my room.

CHAPTERTHREE

Aunt Rita is in the kitchen the next morning when I go for breakfast. Unlike Mary Beth, she looks the same way she did two years ago when we went to Nebraska for Christmas. She’s as tall as my mom when she wears high heels, and she always wears them. Opposite of Aunt Mary Beth, she’s skinny, and her face is all tight like her bones are about to pop through. This morning, she’s talking fast and searching through the kitchen cabinets, just as fast.

“I can’t believe it. My plane gets in late. Then I find out the damn ferry quits running at seven o’clock. Can you believe that?” She goes on before anyone has a chance to answer. “I even told the guy running the fuel pumps at the dock that I was willing to pay fifty bucks to get across the bay. But apparently, gas jockeys make so much money he could turn me down. Can you believe that?”

No one even tries to answer this time.

“I ended up having to get a motel room for the night, and then I caught the first ferry out. Where in the hell are the bowls? I need one for my yogurt.”

“Up there.” Nana points to a cabinet. I’m positive I saw Aunt Rita open it already.

“Then the motel charges me a fortune.”

She suddenly stops, looks at Nana, and smiles.

“I guess we can afford that now, can’t we, Mom? Have you hired an attorney to get, you know, things arranged yet? That’s a lot of money. I hope it’s someone we can trust.”

Two things. My Aunt Rita, Margarita is her real name, but no one ever calls her that, is a lawyer in Chicago. Dad said she works for a firm that specializes in civil law, whatever that is. He told me it means that she rarely goes to court since the parties prefer to settle, and no one ever goes to jail. Second, I noticed she used the word “we” when she talked about the money Nana won.

“I’m sure Momma’s already done that. Right, Momma?” Mary Beth asks.

“Yes, I already set up a trust,” Nana Belle answers. “Stan Daniels helped me. He’s been our family lawyer for years, and I trust him.”

“Stan Daniels?” Rita squeaks. “What is he, a hundred years old by now? Hell, he was old and cranky when I was still in high school.” She turns and glares at Nana, hands on hips. “You’re playing in a whole new ballpark now, Mom. Daniels was competent for when Dad died, and we had to probate his estate. But that’s nothing compared to now.” She snorts. “Your game just got upped. A hundred million. Hell, it takes skill to work with that amount.”

“It’s a hundred and nine million,” Mary Beth says.

“What?”

“Momma won a hundred and nine million, not a hundred.”

Rita waves a hand, dismissing her sister. “A hundred, a hundred nine, what the flip. It’s a damn lot of cash. Too much for some little country lawyer to sort through.”

“Momma,” Mary Beth says. “You do what you want with it. You know I love you and whatever you decide to do is fine.” She pauses. “I know you love us, too, and you’ll do what’s best for your family, right?”

My mom joins us, hair still damp from the shower.

“Morning, Rita, glad you made it.”

She kisses the top of my head. “Morning, sweetheart, you sleep well?”

“Yes,” I say, “but I’m starving.”

“You ate a ton last night, Henry, and you’re still hungry?” Mary Beth huffs. “What is it with boys that age? All they think of is food.”

“He’s growing fast.”

Go Mom. My aunt really can’t complain since she obviously eats. A lot.

Mom finds the cereal and pours us each a bowl. “What’s the plan for today, Mom? You said you wanted to get together and talk with us.”

“Mom said old Stan Daniels set up a trust,” Rita tells her, spooning yogurt into a bowl. “I’m wondering if the old coot is even competent to do something so complicated. We have skilled estate and trust attorneys in our Chicago office that I’m sure would be better. What does the trust say, anyway, Mom?”

Nana starts to answer, but Rita keeps on going. “And then there’s the matter of money management. You’ll want to invest so that the trust can grow and provide a suitable income for you. Are you saying Stan’s going to do all that, too?”

Again, Nana starts to answer, but again, my aunt runs right over her.

“There’re all kinds of cons out there that would be glad to assist,” Rita's fingers make quote marks in the air when she says ‘assist.’ “And then poof, your money disappears along with the adviser. She makes quote marks around ‘adviser,’ too. “I can’t tell you how many clients we have that this happened to.”

“Clients who are victims, or who perpetrated the fraud?” asks my mom, all innocent-like.

Rita glares at Mom, but my mom is concentrating on pouring orange juice, so she doesn’t see.

“All kinds. That’s why I know how easily Mom can be separated from her winnings.”

“Girls, stop, please,” Nana says, putting her hands over her ears. “All this bickering has to stop. For God’s sake, you’re all adults now with your own lives, but here you are acting like children. When I’m gone, you three girls will be all the family that’s left. I want you to love each other, spend holidays together, turn to each other for support.”

“But, Momma, we’re all very different,” Mary Beth says.

“I know, honey. Rita’s a successful lawyer. Jen teaches, that’s an important job, and you,” Nana turns to Mary Beth, “you have a busy life with your three daughters.”

“And I help Stephen in his real estate business,” Mary Beth huffs. “Plus, when the girls all get in school, I plan to finish my degree so I can work as an LPN.”

“Yes,” Nana says, drawing out the word, “and how is Stephen’s business doing, anyway? He always tells me he’s doing great but then again, you asked for—”

“What?” Rita jumps in. “Did you ask Mom for money already? After all the bragging Stevie does about the big deals he puts together?”

“His name is Stephen, I’ve told you that before, and we just asked for a little loan to tide us over. He has expenses, you know, and it’s not like he has a regular paycheck. Sometimes we have to wait a while for his commissions to come through.”

“Mom’s right,” my mom says. “We’re family here. We have a shared history. Even though some parts were difficult with Dad, we’re all grown now and it’s time to get past all that.”

“You just tell us what you want to tell us, Momma,” Mary Beth says.

Finally, no one is talking. I jump right in. “Mom, can I be excused so I can go outside?”

“You’re excused, Henry. Put your dishes in the sink, first, and don’t wander too far.”

I stack my bowl and spoon in the sink and escape.

A wood-planked walk leads down the hill from the house to the beach. The sun is out now, and I can see sand between the scrubby grass and the ocean. Living in Seattle, I know about the Pacific Ocean, but the Atlantic is different. The water here is a blue-gray and makes soft waves that chase my bare feet. I play catch with the waves, chasing them toward the ocean and jumping over the line of shells that have clumped at the tide line. Then I run back, again leaping over the shells.

A dead jellyfish has washed up, the round clear body like a bubble. When I poke it with a stick, it doesn’t move. I poke harder and the jelly inside it squishes to the side. Poke, squish. Poke, squish. Just to make sure it’s dead.

The beach curves around the front of the house and ends at a thick bunch of trees. In it are palms with their narrow trunks topped with fan-like leaves: tall, twisty trees with hairy clumps of Spanish moss, low bushes, and vines like ropes that dangle off the trees toward the ground. I put my sandals on and push through the shrub and vines. The ground is thick with dead leaves and stuff.

I’m an explorer deep in the jungle. I’m stalking wild beasts, walking really quietly, and getting closer and closer to a spotted panther.

Overhead, something chatters, and I quickly back out, vines grabbing at my ankles.

Blood-sucking squirrels, that’s what lurks overhead, I discover when a little gray creature jumps from branch to branch chattering a warning.

I walk along the forest edge, past the beach house, and discover a place where the shrubs aren’t as thick. I look around to make sure no one is watching, and then step into the deep green shade. No blood-sucking squirrels here. Good. It’s hard to walk; dead leaves and stuff hide feet-trapping roots. I hear skittering noises. Snakes? Giant people-eating bugs? Panthers? It’s spooky and, except for the skittering, so quiet I can almost hear the trees breathe. Something bites my neck, and I slap at it. Creepola, it’s a blood-sucking, vampire mosquito.