Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Max Lomax

- Sprache: Englisch

'Like a darker, grimier version of Mick Herron's Slough House novels, this is a highly promising debut.' Mail on Sunday 'Mesmerising'. The Financial Times A senior civil servant dies in suspicious circumstances. A sensitive file in his possession and evidence of contact with a human rights lawyer lead the authorities to believe he is a whistle-blower. This needs a police officer used to operating in the murky world between policing and intelligence. DS Mark (Max) Lomax is a former Special Demonstration Squad officer – a Special Branch unit dedicated to infiltrating political and extremist groups, a world he thinks he has left far behind. Following a botched stakeout of a north London gangster, he finds himself on enforced leave and is called back into his old world of half-truths and conflicting agendas. As he digs into the death of the civil servant, Max is obstructed at every turn, forcing him to turn to the people he once betrayed for help. With political reputations on the line, the case becomes less about uncovering the truth, than burying it for good.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 453

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

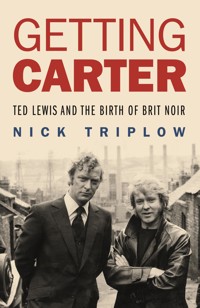

Praise for Nick Triplow

‘An exhaustively researched, brilliantly crafted recounting of the turbulent life of one of crime fiction’s most influential authors’ – Howard Linskey on Getting Carter

‘Triplow manages to extract several noteworthy points from what might seem to be the unprofitable wreckage of a wasted life – a major achievement as he has had few primary sources to work with’ – Nicky Charlish, 3am Magazine on Getting Carter

‘Exhaustive, informative, incisive and a damned good read… you’re in for one hell of a ride’ – Martyn Waites,Crime Timeon Getting Carter

‘Triplow is unsentimental in his study of a man whose work offers much to admire. Perhaps this fascinating portrait is the beginning of an overdue revival’ – Ben Myers, New Statesman

‘Triplow does a fine job of demonstrating why Lewis’s work should be rediscovered’ – Jake Kerridge,Daily Telegraph on Getting Carter

‘Triplow’s writing is always elegant and perfectly at the service of the material’ – Barry Forshaw,Crime Time

Look into my eyes See the descent of a nation

James Varda – Just a Beginning

Part One: February 2006

1

Max

Tottenham, London N17

Saturday 18 February, 01:13

Everyone told Max he was wasting his time. Andre Connor wasn’t coming back to Tottenham. Two weeks surveillance in a dank flat on Mount Pleasant Road paid for out of his own pocket and Max was ready to concede the point. One more night, he told himself. He shut out the cold, narrowing his focus until there was only him and the terraced house across the street.

Street detail blurred into shadow as minutes and hours passed. He came away long enough to rub the tiredness from his eyes and was back in time to see a group of kids amble into view, patrolling the postcode. A tight little crew, this lot. They dressed well, which meant someone was paying. Max reckoned it had to be Connor. They made their way towards Lordship Lane like they owned every inch of pavement, which effectively they did. A lad on a bike Max hadn’t seen before rode alongside for a time, pulling stops and wheelies, then jumping the kerb and heading north, leaving the others to turn back towards the estate.

A shouting match broke out between the sisters from the flatshare three doors down. Sounded like it had been brewing indoors before they brought it to the street: Sister One claiming Sister Two had ripped off her phone and racked up a bill neither could pay. Sister Two said Sister One was a tight bitch and she’d paid for the phone in the first place. Sister One said Sister Two never paid for a thing in her life. The spat grew louder, more vicious. A police patrol car came by. A second car and van pulled in behind. It took half a dozen uniforms to calm the girls down and persuade them back inside.

Max noted the time, 2.43am.

Twenty minutes later, the uniforms drove away and the neighbourhood locked itself down for the night. A black dog loped from an alleyway into the arc of a streetlight, cocked its leg and sauntered back to the shadows.

After that came a lull. Max lost track of time; his thoughts drifted as boredom set in. His mind wandered into dark places, dipping in a well of what-ifs and if-onlys, pulling out every lie he’d told, every time he should have stayed quiet, every time he’d screwed up. He saw the faces of people he’d lied to, people he’d hurt, settling on a line from the song he’d listened to last, walk away – in silence. He repeated the words like a mantra until they lost their meaning and slipped away.

The drizzle that had fallen since early evening turned to rain. Rain from the cracked gutter dripped against the outside wall. Some nights it was so loud he could barely think. Tonight, it gave him something to listen to that wasn’t that nagging inner voice revisiting the chain of events that brought him here. DI Redding maintained the guns Connor was known to have stockpiled somewhere in north London were at his girlfriend’s flat in Bounds Green, because that’s what Tanesha Dorgan had told him. Tanesha was a player in her own right; she was also Connor’s cousin and her story of a petty rift between them over money hardly justified selling out Connor, who’d raised her when her mum died, bringing her through the ranks of his crew as soon as she was old enough. But Redding had invested in Tanesha and wanted what he’d paid for.

Max disagreed.

Redding said nothing at the time, summoning Max back later and telling him he didn’t like being called out in front of his own team. If he was so sure, go his own way and run his own damn surveillance. Redding was serious. Max was to provide daily written reports, accounting hour by hour, sharing every scrap of intelligence. He couldn’t help thinking he’d dug himself a hole and Redding had walked him in. For weeks, he made those few square miles of north London his ground, walking the streets, tea and toast in the cafés, making himself a regular in the pubs. He’d blagged games of darts with locals in The Ship on the High Road, bought pints and had them bought for him. What they knew, he knew. All Redding had to do was trust him, but he wasn’t about to do that. So he’d taken on the flat, paying up front out of his own pocket. Fourteen nights being Billy No-Mates and he had nothing to show for it other than creeping self-doubt and a stiff back.

He took a break, rubbing warmth into the backs of his legs. He pulled his coat around him. It gave off stale cigarette smoke and something of the flat’s fustiness. That smell had got into every scrap of fabric in the place – the curtains, the rug, the sofa where he slept in daytime. He reached in his pocket for the last cigarette, the one he’d been keeping for morning. What the fuck, he’d toss for it. He balanced a ten pence piece on his thumbnail. Make your choice, he thought. He flipped. As he grabbed for the catch, there was a flicker of light in Connor’s house. The coin hit the carpet and rolled onto bare boards.

Max refocused the night scope as a shape passed left to right across Connor’s upstairs window. When the second pass came, he was certain and reported the contact. He heard static. He sent DI Redding a text: Connor came home.

A dark SUV cruised by and turned into Adams Road. When it came back the other way moments later, brake lights glowed red and it pulled to the kerb. Its occupants sat tight, waiting. Max couldn’t say for sure who was in the car with the rain and net curtains between them. His earpiece crackled. Redding demanded a call sign and codeword.

Max got to the point. ‘I’ve got movement here. Three IC3 males in an Audi Q7 and one other in the target address.’

Silence.

‘You get that?’

‘Do you have a confirmed ID on the target?’ Redding wanting Max to be wrong.

‘It has to be him.’

‘That’s not what I asked.’ A longer silence. Thinking time. ‘We’re about ready to go at the Bounds Green address. I’ll get some people to you once we’ve secured this place. Stay put.’

The men stepped out of the Audi and went inside the house. A light came on in the upstairs room. The curtains closed. Shortly afterwards, the driver came out of the front door. Max hadn’t seen him before. He’d have remembered; the guy was like fat fucking Larry. Larry checked the street then stuffed himself behind the wheel. A second man followed, carrying two large holdalls that he lifted into the car’s open boot.

Max updated Redding.

‘Enough. Backup’s on its way, just wait and hold your position.’

Max cut the link.

The Audi stayed parked, engine idling, Fat Larry smoking. There was no other movement. Max sensed the entire neighbourhood knew the score. Ten minutes since he’d called in. He whispered to himself, ‘C’mon, what are you waiting for?’

The answer came with a rattle of the downstairs door handle and the crack of a bolt being forced. Evidently, not backup. A low murmur of voices in the hall. Two at least. Max slipped his coat over the chair, adding a body-shaped shadow in the darkened room, knowing it wouldn’t fool anyone. He crouched out of direct sight-line of the door and listened to footfall, heel to toe on the stairs. Stair seven gave a hollow groan.

He shouted, ‘Police, drop your weapon.’

The first shot split the door panel and sent a thick splinter into Max’s cheek, knocking him off his feet. A second thudded in the plasterwork behind him. A third, presumably aimed at the coat, shattered the window. He held his breath, frozen, waiting. Couldn’t have been more than seconds. He heard them go downstairs and followed, vaulting the last half-dozen stairs. Twenty feet behind, walking on broken glass in the kitchen and gaining through the backyard. They saw he was following and fired two shots blindly behind. Max’s feet slipped from under him on the wet path, palms stinging as he broke the fall. He picked himself up and gave chase through the alley between the houses into Mount Pleasant Road, then into the estate. They ran without looking back and split by the community centre. Max followed the slower of the two towards Willan Road. He turned the corner and almost ran into the parked Audi, doors open, occupants waiting: four masked, hooded figures; four handguns aimed at him.

Max stopped dead, his chest heaving. Rain soaking through his sweater. He kept his arms away from his body and caught his breath. ‘I’m a police officer. I’m unarmed. You want to see some ID?’

‘I know who you are.’ The voice muffled behind a red scarf. ‘I know where you eat, where you drink, where you shit.’

One by one the gunmen retreated to the safety of the Audi until only the last was left. Andre Connor pulled the scarf from his face. He lifted his gun high, walked up to Max and pressed the business end firmly against his forehead. ‘Down on your knees.’

Max felt blood run warm down his face. His teeth bit on splintered wood and he spat.

Connor pushed the gun harder. ‘On your fucking knees.’

Max made eye contact. ‘Not in this life.’

‘You know what this is gonna look like?’ said Connor.

Max imagined news footage zeroing in on the moment of impact. His body dropping. Cold, grey silence. It would look like what it was, a police officer killed in the line of duty. For the mute witnesses in the glow of phone screens in Stapleford House, it would look like a settled score. Another line in Andre Connor’s legend. For every fucker with an opinion to sell, it would be content.

Connor said, ‘That’s my mum’s house you’re snooping on.’

‘She’s not there now, though, is she?’

Max felt Connor’s grip tighten. This was the moment.

Connor looked up at the windows. ‘My streets. My neighbourhood. My estate. I own it like I own you right now. I see you again…’ Connor dragged the barrel across Max’s forehead, twisting it into his eye. ‘I will shoot your fucking eyes out.’

Connor gave a nod and the Audi reversed slowly. Fat Larry behind the wheel, Tanesha Dorgan in the back, phone pressed to the window filming one for the family album.

‘My estate, remember that.’ Connor climbed in and they were gone.

The sun dragged itself over the houses on Mount Pleasant Road as Max sat on the arm of the chair by the broken window. He held a wad of gauze to the wound on his cheek. The paramedic said he’d need stitches and a tetanus shot. DI Redding wanted to see him first – just arrived, now hunched in the rain in conversation with a uniformed sergeant in the street below. Max was distracted by the bullet buried in the plaster just above head height. Closer than he’d realised. Waiting gave him time to think through the night’s events: changes in the street’s rhythms he’d failed to connect; the foot soldiers calling it a night too soon; the messenger on the bike; even the sisters’ screaming match distracting the community police team. Connor had known he was there. The rest had been a show for his benefit.

Redding’s tread was heavy on the stairs. He threw a cursory glance at the door panel shot to matchwood and ran his fingers through thinning hair – he hated getting his hair wet. ‘You got a towel?’

‘Bathroom. Second left.’ Max nodded towards the corridor. His tongue felt fat in his mouth.

Redding came back, gently rubbing his hair with Max’s ragged blue hand-towel. ‘So, you want to tell me why you couldn’t wait ten minutes?’

‘You didn’t have ten minutes.’

‘I told you to stay put. Your brief was to observe and report.’

‘Did you find anything?’

‘What?’

‘Bounds Green, Connor’s girlfriend. Did you find anything?’

‘Not as yet.’

Redding turned to leave, then changed his mind. ‘I took you on because you were an experienced officer. I was told my people would benefit from your knowledge, your influence. It’s not working, is it?’

It wasn’t true. Redding had accepted Max under sufferance because he’d shown himself incapable of handling organised operators like Andre Connor.

‘Yeah,’ said Max, ‘which part of being your asset did I get wrong exactly?’

Redding picked his words precisely, as if he’d drafted his statement on the way over. ‘The part about being a lone police officer pursuing armed suspectsinto Broadwater Farm Estate without due consideration for yourself or my operation, and against my explicit orders. That part.’

‘And what about Tanesha? Sends her love, by the way.’

Redding ignored the comment. He scanned the room. ‘I don’t know how you live like this. This place is disgusting, a bloody tip.’ He tossed the soggy towel on a chair.

‘You want me to get a cleaner?’ Max fished the flattened pack of Marlboro Lights from his coat pocket and lit his last, slightly bent, cigarette.

2

Tyler

Oakwood, London N14.

Saturday 18 February, 15:20

Michael Tyler came out of Oakwood Station and took his bearings. The fog had barely lifted. Traffic was slow and exhaust fumes caught the back of his throat. He pulled off his gloves and reread the directions he’d written down. He took his place in the bus queue. Unfamiliar route numbers and names of places he’d never been made him feel a long way from home. He wrapped his arms around himself against the cold. Even with the extra thick socks Emily insisted he wear, his toes were numb within minutes. He fumbled through layers of clothes for his watch. By the time the bus sailed through the murk and pulled to a stop, he was late.

He sat downstairs on the bus and watched tree-lined suburban streets pass, looking for the church he’d noted as a landmark and wishing he was in the spare room at home, quietly researching the Tyler family tree as he did most Saturdays. But this was important, he assured himself. The previous evening he’d had a call from Patrick Theobold, senior consultant in the director’s executive team, asking if he’d retrieve a file from the director’s home address and return it to the department on Monday morning. He didn’t go into the specifics over the phone, but there was, he said, the issue of a ‘classified data breach’ – something on the file that ought not to have been there. He rattled on about ‘documents sent in error’ and needing to ‘avoid embarrassment’. After thirty years as a civil servant, the last fifteen in the Home Office, Tyler had said yes without thinking.

As he approached Derek Labrosse’s home on the outskirts of Enfield Town, the porch light came on, but it wasn’t the director who opened the door before he’d had a chance to ring the bell. The woman looping a pale grey silk scarf around her neck was clearly irritated at being made to wait. ‘About time,’ she said. ‘I’m supposed to be meeting my daughter in town at four.’ She spoke over his apology, waving away the ID badge he presented for her to check that he was who he said he was. A clutch of thin wooden bangles slid down her wrist. ‘Christ knows why this couldn’t wait until Monday. You’d better come in. And wipe your feet, will you, I’ve just had the floors polished.’

Tyler did as he was told.

She softened a little. ‘Jesus, you’re freezing. Do you want a hot drink, I could heat up some coffee from this morning, if you don’t mind it nuked?’

He must have looked confused.

‘Microwaved.’

‘Please, that would be lovely.’ Tyler pocketed his gloves and warmed his backside against the hall radiator. A series of muted modern paintings hung on the walls. Thick oil-textured rusts and browns; spindly wind-bent trees edging unploughed fields. He looked up at a wide open-plan staircase which opened out on a galleried landing and a series of wooden panelled doors. The air was thick with the smell of furniture polish.

‘It’s a touch on the grandside. I always feel I ought to wear a ball gown when I come down for breakfast.’ The woman smiled and handed him a mug. ‘We’d better get on with it. I’ll take you up to Derek’s study.’

Tyler followed up the stairs. He stood aside while she unlocked a door at the far end of the upstairs gallery. A monumental desk filled a third of the room, its leather top littered with not-so-neat piles of paperwork. ‘Presumably you know what you’re looking for.’

Patrick Theobold’s direction had been unambiguous: the file would be in a green cardboard jacket, stamped Confidential, and have a unique reference number. The way he described it, Tyler assumed it would be ready to collect. He showed the woman the reference.

‘That means nothing to me.’

Tyler scanned the loose papers, shelves crowded with books and management journals, battalions of box and lever arch files, and a squat oak filing cabinet. ‘It’s difficult to know where to start.’

‘I really don’t have time for this.’ She keyed some numbers into her phone and waited. ‘Bugger, he’s not answering… Derek, look it’s me. I just wanted to let you know Mr…?’

‘Tyler.’

‘Mr Taylor is here to pick up this file your people called about. I’m supposed to be meeting Ruth from the train at four. God knows what time I’ll get there. I’ll leave my car at Oakwood and give Mr Taylor the keys to lock up. We’ll see you later for supper.’

She ended the call and issued instructions about which keys fitted which locks, which he should leave unlocked and to post the keys back through the letterbox. Her boot heels sounded hard on the wooden staircase. When she slammed the front door, the house shook.

Tyler unzipped his jacket. He told himself that, by working systematically, he’d be done and home sooner. On the way he’d buy flowers for Emmy and a bottle of Merlot to go with the lasagne she was cooking for their dinner. He had told her only that he was going into work and given an excuse about preparing for a meeting that had been brought forward unexpectedly. Mr Theobold insisted the task remain confidential between the two of them. She’d given his hand a sympathetic squeeze before he left and asked that he call when he was on his way home.

He pulled box files from the shelves one at a time, leafing through the contents until only the desk remained to be searched.

The desk drawer opened part way, then stuck. He tugged sharply and it opened fully, sending a muddle of notes, receipts and paper-clipped theatre tickets fluttering to the carpet. Beneath a stack of correspondence was an A4 manila envelope, sealed and addressed to Mr Jonathon Coles at an address in St Albans. Most of one corner had been torn – the result, he assumed, of his wrenching the drawer open. A green cardboard cover was visible through the tear. Tyler slit the envelope seam from its ripped corner, pulled out the file and checked the reference, 62A/47/09.

He stared at the file for a few seconds, trying to make sense of how it had been in the possession of anyone from his office, let alone how it was mistakenly sent to the director or was being forwarded to what appeared to be a private address in St Albans. Mr Theobold said that, if he returned the file, its absence would be overlooked. Any problems, contact him and only him. Tyler flicked through the first few pages, absorbed by what he was reading. It was inconceivable that such privileged information had ever been allowed to leave the building. Correspondence between directors and ministers was subject to strict protocols. He’d seen enough to realise 62A’s confidential designation was woefully underpowered. Tyler told himself he didn’t need to know. All that mattered was that he’d accomplished the task. He closed the file. As he stood up, something made him look behind. Derek Labrosse filled the doorway, red-faced, running his gaze over the chaos of his office. ‘Who the fuck are you?’

Tyler’s heart thumped. He slid the file back into its envelope. ‘I’m sorry. I was sent to pick this up and bring it back to the office.’

Labrosse motioned for him to put the file on the desk.

‘Is there a problem?’

Labrosse raised an eyebrow. ‘Other than you breaking into my house, ransacking my office and reading classified material? No, no problem at all.’

‘Your wife let me in. She left you a message. Please, check your phone. My name is Michael Tyler. I work in the third floor registry.’

‘It comes to something when they send an amateur from my own department. What’s your end of this, you getting paid? Or you doing someone a favour?’

‘Neither. Please, you need to ring Mr Theobold.’

Labrosse snorted. ‘Theobold. That makes a kind of sense. Him and the Americans. What about Lillico, is he a part of this? Of course, he is. Who else?’

Tyler tried to remember, had Theobold mentioned other names? ‘I don’t –’

‘Don’t tell me you don’t know.’ Labrosse slapped his hand down hard on the desktop. The keys dropped from the drawer. ‘Who else?’

Frightened to say he didn’t know a second time, Tyler shook his head.

‘Bugger this, we’ll let the police deal with it. You can explain to them. Stay here.’

As Tyler remembered it, what he did next was the result of fear; it paralysed his thinking in a way that made the irrational seem perfectly sensible. All that mattered was removing himself from the situation, the wrongness of it suddenly blindingly obvious. Others would have to explain. He put on his coat and picked up the envelope containing the file. As he started down the stairs, Labrosse was coming to meet him. ‘I told you to stay.’

‘I’m sorry, I have to go.’

Labrosse snatched at the file. It slipped from the torn-open envelope. Off balance, Labrosse lurched backwards, his free arm flailing for a non-existent banister, striking Tyler in the mouth, then clutching air. In almost comical slow motion he struggled to regain his footing, trying to correct the bizarre backwards stride he’d taken. He twisted, stumbled and fell. His face hit the stairs, wrenching his neck. He slumped on his side to the bottom stair and was still. Blood spilled from his nose across the newly polished floor.

Tyler was in the bathroom for a long time. Labrosse’s backhand had split his lip and he let it bleed into the sink. He rinsed his mouth and washed his face in cold water, letting the tap run until the blood disappeared. He dried his face and refolded the towel, placing it on a pile of fresh laundry in the airing cupboard. A week’s worth of crisply ironed white Van Heusen shirts hung on identical padded hangers.

The house was in darkness. The porch light’s orange glow shone into the hall across Labrosse’s body. Tyler made his way down the stairs, stepping carefully over the dead man. His eyes were partially open, the neck twisted, bulging oddly. Until that moment Tyler had known death only as a controlled experience, hospice-clean and in the hands of those for whom it carried a quiet certainty. This was not like that at all: it had blood, the crack of broken bone, and a dead weight fall. It carried culpability. He should call people, he realised that. Tyler dialled Patrick Theobold’s number.

An hour later, he stood at the end of the platform at Oakwood with the file and its bloodstained pages in a Sainsbury’s ‘Bag for Life’. Thinking but not thinking, unable to see more than ten feet ahead as the fog grew denser, muffling the slow beat behind his eyes.

On Saturday evening he thought through what would happen when the police came, running the sequence in his imagination: dark figures crowding the hall, their uniforms and their bulk. An invitation to answer questions as they sat on the edge of the sofa. Where were you this afternoon between the hours of two and five o’clock? And he would have no answers, only the truth. He imagined Emily’s expression when he came clean and brought out the bloody pages from the file.

The police didn’t come on Saturday night. On Sunday, they visited Morden Hall, Emmy’s favourite place for a browse among the gardens and a skinny latte overlooking the wintry pond. Snowdrops were in flower; the daffodils and crocuses wouldn’t be far behind. Back at home, she brought out her sketch pad and pencils. Morden had inspired her, she said. Plans for their own garden. It needed freshening up.

Tyler waited for the knock at the door.

On Monday, he phoned in sick. After breakfast, he locked himself in the spare room, trying to pick up the thread of family history he’d left on Saturday morning. The names and dates held no interest. All the project had confirmed was that he was the latest in a succession of middling achievers: tradespeople, shopkeepers, conscripts and clerks. He closed down the PC and stared at the blank screen. Later in the afternoon, he slept on the sofa in front of The Third Man, waking up to Anton Karas’s zither and Joseph Cotten’s long, long wait for the girl who walks by.

That night they were in bed when the house phone rang once and stopped. He was halfway into his dressing gown, heart pounding. He rested his head on the pillow, wondering if he’d heard the phone or dreamed it. Emmy’s breathing had kept its familiar sleep rhythm. He listened to footsteps in the street outside, envisioning the front door off its hinges, the lock smashed in one blow. His imagining had boots on the stairs, torches shining in their eyes. Hard men with harsh voices. Accusations as they hauled him from bed in his pyjamas. Emmy crying. They were at the front gate, waiting. He was afraid to move, then the voices and laughter grew distant, footsteps echoing in the silence long after they’d gone.

When the children were small, Tyler had developed the ability to rest in a semi-awake state, sensing the slightest noise – those little coughs and cries the kids had – almost before they happened. Sometimes they would want to be held; a few quiet words could bring them back from their bad dreams to a place where daddy would make everything safe. That night he prayed. Our Father, who art in Heaven. Words of comfort, doing for him what he’d done for his children. He slept, but only for seconds. Give us this day our daily bread. Then another noise outside. Then sleep. Then awake. Lead us not into temptation. Temptation, the word repeated. But he hadn’t said the part about Forgive us our trespasses. Or had he? Amen. Amen. Amen. Amen. Please God, don’t let them come.

On Tuesday morning the phone rang three times and stopped.

‘Probably a call centre.’ Emmy kissed him. A friend was giving her a lift.

When she’d gone the phone rang again. Tyler picked up.

It was Theobold. ‘Your mobile is switched off and I haven’t seen you in the office. I was wondering whether you were dead. Apparently not.’

‘I was expecting a call,’ said Tyler.

‘And now you’ve got one.’

‘From the police.’

‘It’s been dealt with.’

‘But I didn’t report what happenedto the police.’

Theobold paused as if conferring with someone else. ‘That won’t be necessary.’

‘They’ll want a statement, and Mrs Labrosse –’

Theobold said, ‘I’ve given the police the statement you gave me over the phone. Mrs Labrosse is being supported by us and by her family. Everything else is taken care of. I can clarify any other issues when you come into work. Tomorrow would be good, if that’s okay with you. Don’t forget the paperwork.’ He hung up.

That evening when Emily came home, she tossed the Evening Standard on the table open at a photograph of Derek Labrosse.‘One of the girls at work showed me this. Didn’t you know him?’

Tyler shrugged. ‘I met him once or twice in passing.’

He changed the subject, talking about booking a weekend away at the coast, but Emmy wasn’t deterred. ‘You must have known of him, people always know things about people.’ Her smile grew thinner.

Tyler forked through the leftovers on the edge of his plate. ‘Please can we let it go? I’m not going to gossip about someone I hardly knew.’

Emmy cleared the dinner things, crockery and cutlery clattering in the dishwasher. When she left for her evening class, Tyler retrieved his old brown briefcase from the cupboard under the stairs. He worked the combination and clicked the catches. He spread File 62A’s contents across the kitchen table. Some loose pages were stuck together with blood. Those that were difficult to separate, he steamed over a boiling kettle. He moved everything upstairs to the office, turned on the computer and scanned a Home Office letterhead. He retyped the content of the spoiled pages using the same corporate font, then printed and filed the copies in date order, marking their file number identically to the originals, destroying each blood-stained page as he went. It wasn’t perfect, but it would do.

Just after ten o’clock, he heard Emmy’s key in the door. There were, he counted, six pages stained to varying degrees that he hadn’t had time to retype. He locked them back in the case with the doctored file and left it under the desk. He came downstairs and kissed Emmy on the cheek. While the kettle boiled for tea, he polished his shoes ready for the morning.

Second carriage from the front on the 07.12 to Victoria Station. He opened the biography of Francis Walsingham he’d been reading. Sunlight flickered between city buildings across the passengers’ faces. As the train movement rocked him to sleep, his grip on the book loosened and it fell through his fingers. Jerked to consciousness, he reached down to pick it up and touched the hand of the woman sitting next to him. He sensed the other passengers measuring the mishap and his reaction to it. He straightened the book’s creased corners, thinking how closely they watched.

In the office, he placed the file in a new envelope, resealing and taping the seams and placing it inside another envelope as Theobold instructed. He addressed the outer envelope and took it upstairs to the Director’s office. The atmosphere was subdued, the Director’s PA had been crying. He handed over the envelope. ‘It’s for Mr Theobold.’

‘I’ll see he gets it when he comes out of his meeting.’

As he walked down the back stairs to his office, it struck him how easy it was for people like Patrick Theobold to construct their morality in a way that allowed rule-breaking without consequence. He’d never been one of those people. For him, without honesty there was no release.

Theobold found him later as the afternoon team meeting broke up. His appearance hurried Tyler’s colleagues from the conference room. When they were alone, he closed the door and sat next to Tyler, clasping his hands in front of him. Tyler stared ahead.

‘What did you make of it?’ said Theobold.

‘I didn’t read it.’

Theobold smiled. ‘Of course not.’

Tyler turned in his seat. ‘You knew full well that noone in my office could have had hands on that file. Why did you send me?’

‘Think of yourself as a courier.’

‘He thought I was stealing. And he was right wasn’t he? And his wife – oh my God, his poor wife. She needs to understand what happened.’ Tyler took off his glasses, rubbing his eyes.

‘Give me those.’ Theobold took the glasses, removed a cream silk handkerchief from his breast pocket and polished the lenses. ‘Do you think she has a right to know her husband came home half-pissed and fell down his own stairs – surely you realised he’d been drinking. Or perhaps we could tell her that instead of delivering government policy, he’d been working to undermine it and contravened the Official Secrets Act in the process. Do you think that would be a comfort to her right now?’

‘Can I have those?’

Theobold lifted the glasses to the light. ‘What I’m doing is supporting you, Michael. Just as I’m supporting Mrs Labrosse.’

‘I should go to the police.’

He laughed. ‘For what reason?’

‘To explain for Christ’s sake.’

Theobold refolded the handkerchief, picking it off the table like a cabaret conjurer, fussing until it was perfect with three peaks visible in his breast pocket. ‘I can see why you’d think that might be the right thing to do, but ask yourself, who gains? Certainly not you.’

Tyler said, ‘I think the police –’

‘Your conscience. Is that what this is all about? You feel bad?’

‘Of course, I do. Bloody terrible. Please may I have my glasses?’

‘But the police aren’t interested in you, are they? They’re satisfied there’s no case to answer. The coroner will deliver a verdict of accidental death, which according to you is what happened. Am I right?’

Tyler nodded.

‘So, if you present yourself now, you’d just be muddying things and making the police appear incompetent. Though I do admire your honesty.’ He placed the glasses back on Tyler’s face, settling them gently on the bridge of his nose. ‘Better?’

‘Yes. Thank you.’

‘Just be aware of the pressure you’d put yourself and your family under. It would be far worse than you imagine. You’d lose your job for a start. There’d be a court case. You don’t strike me as the sort of person who’d keep up a principled stand in the dock for very long. That’s aside from the cost. Legal representation does not come cheap. Go cheap and risk a custodial sentence. Are you ready to tough that one out? What if the CPS decided somehow that it was manslaughter? It’s not impossible.’ He patted Tyler on the back and went to the corner table, tilted one of the flasks and poured a coffee. ‘Some left, you want one?’

Tyler’s hands were shaking. ‘It doesn’t alter the fact that you sent me to the Director’s house and before then I’d never touched that file.’ His voice dropped. ‘I should tell the police I was there. I’ve made up my mind.’

Theobold emptied a carton of creamer in the cup. He walked towards Tyler and slapped him hard across the cheek. His glasses flew across the table and over the edge. Instinctively, his hands rose to protect his face. When he dropped them a few seconds later, Theobold hit him again, harder than the first time. ‘You want this? Is this what you want? What it’ll take for you to understand?’

He flinched again when Theobold sat next to him. As the ringing in his ear subsided, Theobold’s voice took on a note of concern. ‘Please Michael, take my advice, you really don’t have a choice, so put the thought out of your mind. No one wants it. And you wouldn’t be able to handle the consequences. Understand?’

He swallowed hard. ‘Yes.’

‘Do. You. Understand?’

‘Yes.’

‘Say it.’

He looked up, tears pricking. ‘I understand.’

3

Max

Max slept a lot in the first week of his suspension. After that, barely at all. He stayed close to home around Swiss Cottage. He’d paid cash for his second-floor, one-bedroom flat in Goldhurst Terrace after a windfall some years ago. It had been legal, if not entirely above board. Either way he’d taken advantage of the last, brief window of affordability for someone like him in a neighbourhood like this. It wasn’t an especially affluent part of London compared with others nearby, but it still priced out most Londoners. Max was content here. His corner of NW6 was home and sanctuary. A world away from the noise of the job. It had his books and records, and a framed Down By Law film poster on the wall.

On Friday morning, he received the call he’d expected, inviting him to a session with an HR welfare officer. Certain this was DI Redding looking to force him out, he said he couldn’t talk and hung up. But somewhere along the chain of command the decision was made for him. A second call later that day made it plain, he was to make the appointment. Damned if he did, damned sooner if he didn’t. He said he needed the weekend to think about it; he’d get back to them on Monday morning.

There was something he needed to do first.

The morning of the appointment was clear, bright and cold. Max dared to think the worst of the winter had passed as he walked the short distance from Victoria to a Georgian townhouse on the corner of Ebury Street.

The receptionist buzzed him in, leading him through to Sally Meehan’s consulting room: a neutral space decorated with the kind of artless prints sent as freebies from your friendly office stationery supplier. Maxdropped into one of the two easy chairs, recognising the counsellor’s voice – soft, posh Geordie – somewhere in another room. In their phone conversation she’d assured him she had a track record of tidying up the lives of men who lied for a living. It had sounded like a threat.

She breezed in on the dot at ten-thirty and set her laptop on the table. As she leaned over, a small gold crucifix dropped out from her sweater. She replaced it quickly, ordering her notes, resting them in her lap. ‘So, Mark, it’s good that we can meet finally. Before we start, I want to explain what I’d like to get from the session and we can take it from there.’

‘People call me Max. From my surname, Lomax.’

She didn’t ask why. If she had, he wouldn’t have told her. Covert operations meant creating an identity close to your own. In his previous job he’d been Max for so long he answered to no other name. It was who he was.

‘As you know, Max, we should have been having this conversation last week, but you didn’t want to do that, which makes it doubly important that we make headway today. Otherwise I’ll need to submit a report which says you’ve decided not to cooperate and, based on the statement of your senior officer and several colleagues, you’re unfit for work and unlikely to return for the foreseeable future, if at all.’ She twisted a biro between her fingers. ‘Inspector Redding has accepted you were working under extreme pressure and that your reaction was –’

‘Justified.’ He sat back in the chair.

‘Not exactly, but we can start there. Pursuing suspects into Broadwater Farm without support from colleagues and against DI Redding’s orders, you feel that’s justified?’

‘In context, yes. Andre Connor was an important target. Still is as far as I know. I was attempting to arrest one of his crew. That makes a difference. Shows he’s fallible, gives us a chance to learn more about his intentions and who knows, maybe persuade a young kid there’s a better life possible, one that doesn’t end with him dead on the street.’

‘The suspects were armed.’

‘I’m aware of that.’

She flicked a page from her notes and quoted, ‘In 2003, you were a member of the Special Demonstration Squad under command of the then Detective Chief Superintendent, now Assistant Commissioner, Kilby. On that occasion you also made choices that endangered an ongoing operation.’

Kilby. Out of nowhere, Max sensed the hand of his former mentor, otherwise how had she had access to Special Operations details? ‘That was different, personal. I had a relationship with a woman who was involved with the organisation I’d infiltrated. I’d lived under an assumed identity for an extended period. That kind of thing happens.’

‘Often?’

‘Once was enough.’

‘It says here you were withdrawn because there were doubts regarding your reliability, that you were “politically and personally compromised”.’ She turned another page. ‘According to the file, an independent security services assessment considered you a security risk. You placed yourself and other officers in danger as well as jeopardising the integrity of an operation into a known subversive organisation. You allowed this woman to influence your actions. I’m quoting here, “the officer was manipulated into making decisions that were not in his best interests or those of the operation, suggesting, at best, that his loyalties were split.”’ Ms Meehan looked up. ‘She suspected you of being a serving police officer. You maintained your cover was intact, when you knew it wasn’t.’

Max counted off. ‘One, there were no other officers involved other than my handler, who had no issues at the time and certainly wasn’t in danger. Secondly, the threat within the group, so far as it had been a threat, was nullified. It broke up, a natural process. People move on, they have disagreements, whatever. Lastly, I came out when Kilby ordered me to, because we’d achieved all we set out to achieve. At which time the relationship ended. I moved on.’

‘But you placed yourself at risk. Just as in Tottenham.’

‘That’s not how I see it.’

Ms Meehan closed her notes, folded her hands in her lap. ‘Even if we accept that and even if we back your judgement that you had cause to go after the armed suspects, as reckless as that was, it doesn’t explain this…’ She turned the laptop, lifted the screen and pressed play. Max recognised the raw image of Mount Pleasant Road in CCTV monochrome. ‘We’ve got a man in a hoody with a scarf around his face. Timeline says 03:24, Monday before last. The man walks towards a parked four-by-four. He takes out the headlights with a hammer, then empties a can of liquid over the roof and the bonnet, judging by the effect on the paintwork, some kind of corrosive. A second man appears and confronts him. The second man is assaulted and left on the pavement. The assailant walks out of frame and we pick him up further along the street at which point he drops his hood and is caught cold by a second camera. She paused the footage with Max’s image frozen on screen. ‘So?’

He said nothing.

Ms Meehan persisted. ‘Come on, Max. It deserves a response, doesn’t it? What do you think about that person? Because I think he looks out of control.’

She was wrong. He’d known exactly what he was doing. That night was a parting shot, the sum of his frustrations after months of work, gathering intelligence and setting the operation up. There was no chance of Connor’s arrest now. The guns would have gone, stashed across north London and beyond. He glanced at the screen again, then looked straight at Sally Meehan. ‘Andre Connor thought by shoving a gun in my face he’d owned me. That was my considered answer and it made me feel better.’

‘Considered. I’ll say. This is twoweeks later.’

Max sat up. ‘Do you really want to know what it makes me think? It makes me question why there are CCTV cameras covering Connor’s place that weren’t there before, given that I asked Redding for covert cameras in exactly those locations on three separate occasions. It makes me think that a senior officer is covering himself because he knows he’s not very good at his job.’ He reached forward and closed the laptop. ‘Redding shoved me into that hole with zero support because I challenged his authority. He paid lip service to wanting my know-how, then dumped on me when it wasn’t what he wanted to hear. But what do I think? That it really doesn’t bother me.’

She lowered her voice. ‘The footage alone is enough to have you convicted of a dozen offences. It could get you sent to prison. This…’ she motioned to the closed laptop, ‘it’s a form of surrender. A failure of reason, of training, of common-sense, of instinct. I think when you ran into the estate, you knew Connor would be waiting. I think you wanted him to be. You wanted the confrontation and that worries me.’

She waited for a reaction and when none came, she said, ‘You need to give Assistant Commissioner Kilby a call. If you’re serious about finding a way back, I suggest that would be the route.’

Max shook his head. ‘You’ve read my file. He buried me.’

‘Let me put it another way, you might want to ask yourself how this has been kept quiet. DI Redding was all for asking Connor to make a formal complaint. You’ll need to make another appointment to see me. Come back in a couple of weeks and we’ll talk again. In the meantime, speak to Kilby. Make your decision and I’ll rewrite my report.’

As she wound the session to its close, Max felt a slow release of intensity. His world had become diminished in recent weeks, preoccupied by the thought he’d be forced to resign. But that wasn’t going to happen. Not today and not on DI Redding’s say-so. They drifted into conversation, feeding off generalities until the end of the allotted time. Afterwards, he walked through the streets of Belgravia, past embassies and gated gardens in tree-lined squares. A bright day and Kilby wanted him back. That was worth something.

Part Two: June 2006

4

Max

A hot Saturday afternoon in mid-June and Turnpike Lane was a collision of colours, rhythms, transactions and smells, not all of them legal. Max passed doorways reeking with dope smoke. His first weekend off since he’d rejoined Kilby’s staff, he had no trouble turning a blind eye, slowing his pace to match the afternoon crowd. Sally Meehan had been as good as her word, signing him off on the condition that his work was restricted to back office functions. Since then he’d functioned as Kilby’s proxy in routine meetings, taking on policy research and strategic analysis, if not with relish, at least appreciating the favourable odds of not being shot at. Today was about something else, a conversation with an old friend. Something he’d been meaning to do since that morning in Sally Meehan’s office.

He was drawn by the gaze of a dark-skinned young woman leaning against the open door of a convenience store. In the window a handwritten sign claimed: We Sell Everthing. He returned her smile. She asked if he was thirsty.

‘I’m fine, thanks.’

‘You are tired, buy a cold drink.’ She walked a few steps alongside. ‘I have cold beer in the fridge.’

In the shop it was cooler and darker. Max lifted his sunglasses. A group of older men played dominoes behind a hooked-back bead curtain, the air around them heavy with cigarette smoke. One of the players glanced over his glasses, slamming down a tile to a riot of protest. Max watched the next hand transfixed. The old boys played with the aggression of prizefighters. One guy waved him through. They wanted him to play. The girl was at his shoulder. ‘No, no, no, time for games is later, maybe.’ He got it, by the time they’d finished with him, he’d have nothing left to spend. She drew him into the shop, sweet-talking him through a tour of the crowded shelves, pulling out arbitrary food items – groceries without which, she insisted, his life would forever be incomplete. He came out after ten minutes with Spanish red wine, bread, cheese, apple tea, and chilled Evian. She waved him on his way towards Wood Green High Road. When he looked back, she was reeling in someone else. His shirt smelled faintly of her perfume.

He stopped at an anonymous green front door. A white-on-black embossed nameplate read DELANEY AND COLES SOLICITORS above a faded Legal Aid logo. Max looked up and saw movement at the blinds. He took a chance that it was Delaney not Coles and pressed the intercom: three short rings, one long.

A woman’s voice. ‘Who is it?’

‘It’s Max.’ A silence, the sun beat the back of his neck.

The intercom crackled. ‘I’m working.’

‘Can I come up?’

‘No.’

The intercom went dead.

Max waited a few moments, then pressed again. A pimped BMW slid into the kerb, bass-bins pounding. Three Asian lads gave him the once-over, gunning the engine. After a few seconds, the door buzzed open. He took the stairs two at a time. ‘I think I’ve upset the locals.’

Liz waited on the landing, dress-down Saturday in dark jeans and a pale blue collarless shirt. She lifted her glasses to hold back her hair. She looked tired, the lines at her eyes heavier than he remembered. It had to be three years since they’d last met. There hadn’t been a week go by that Max hadn’t wanted to see her again.

They’d first met soon after he began to infiltrate the activist groups that came together around Green Lanes in the early 2000s. Liz was a notable and vocal presence in meetings at Tottenham Green Centre on Tuesday evenings. Their first proper conversation was at an impromptu post-pub gathering in a flat just off Bruce Grove. In the back room, away from heartfelt discussions of student activists, charity workers, teachers, and a handful of refugees chewing over injustice and real-world suffering, Liz and Max talked mostly about music and books. They’d both been at a Television gig at the Town and Country Club in 1993. On the night, Max had found himself standing next to Robert Plant. Liz ragged him about white boys appropriating the blues. Going their separate ways at dawn, he’d known he was in trouble. His cover as a mature student on an English course at Middlesex University, with little life experience, kept him at the periphery of political debate. As the weeks went by, he discovered that Liz had a watching brief over the groups that used Delaney and Coles’ office as a holding address. It didn’t take Max long to work out that her heart and soul were set on where the real work was. Quietly authoritative, thoroughly professional, Liz was committed to legal activism, making her name by taking on hard-to-win immigration cases against the Home Office. Max had done his research and gradually they were drawn together. Falling in love was the last thing either of them needed. But it had happened and it was real. For Max, it’d never gone away.

Liz said, ‘You know the only white faces that knock at this door are lawyers and police.’

‘It’s not like I’m in uniform.’

‘Might as well be.’

On the landing there were crooked pillars of books, piles of law journals, Amnesty International magazines and stacks of string-bundled files. ‘You moving house?’ Max picked up a loose folder and flicked open the cover.

‘Some of it’s for the shredder, some for archiving and a load of it just needs to be kept out of harm’s way. Since last summer your people have raided once a month.’ She snatched the file. ‘Anyone’d think you had a pain in the arse quota to hit.’

Max held his hands up. ‘Not my people. I’m strictly deskbound. I just do the boss’s legwork.’

‘New boss same as the old boss?’

‘Same boss, as it goes.’

‘You’re still undercover pig for Kilby?’

‘Less pig, more gopher. Strictly above board.’

This wasn’t the conversation Max wanted. It had the hallmarks of their last fretful and increasingly resentful meetings. ‘I’m back with him in the administrative sense. I’ve spent the last month in meetings, in-between organising his archive. The dark and dirty doings of a career in covert policing. You’d love it.’

‘So, he wasn’t purged last year.’

Max gave a little. ‘The consensus is that no one could have – or did – see it coming.’

She nodded. ‘So no one read the papers, saw what two lads from Bradford could do in Tel Aviv and thought maybe it could happen here?’

‘Like I said, whatever loop there was, I’m out of it. Can I come in?’

Liz fingered the faint outline of an old chickenpox scar at her temple. ‘Leave your shopping here,’ she said.

‘It’s a picnic.’ He opened the bag. ‘No hidden cameras, no wire.’

She turned her back. ‘I’ll check it when you leave.’

Delaney and Coles’ legal practice occupied most of what had once been a residential flat over a sari shop. They paid the owners a peppercorn rent as part repayment for a favour. Downstairs, the shop was thriving. From the look of the place, you couldn’t say the same for Delaney and Coles. Max followed Liz through the warren of individual rooms that functioned as offices.

‘These were full a few months ago. Now we can’t get tenants for love nor money. People are frightened to do their work here.’