6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

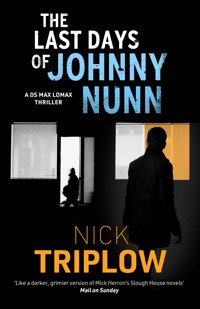

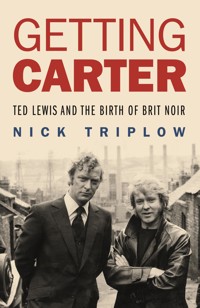

The story of Ted Lewis carries historical and cultural resonances for our own troubled times Ted Lewis is one of the most important writers you've never heard of. Born in Manchester in 1940, he grew up in the tough environs of post-war Humberside, attending Hull College of Arts and Crafts before heading for London. His life described a cycle of obscurity to glamour and back to obscurity, followed by death at only 42. He sampled the bright temptations of sixties London while working in advertising, TV and films and he encountered excitement and danger in Soho drinking dens, rubbing shoulders with the 'East End boys' in gangland haunts. He wrote for Z Cars and had some nine books published. Alas, unable to repeat the commercial success of Get Carter, Lewis's life fell apart, his marriage ended and he returned to Humberside and an all too early demise. Getting Carter is a meticulously researched and riveting account of the career of a doomed genius. Long-time admirer Nick Triplow has fashioned a thorough, sympathetic and unsparing narrative. Required reading for noirists, this book will enthral and move anyone who finds irresistible the old cocktail of rags to riches to rags.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

GETTING CARTER

Get Carter are two words to bring a smile of fond recollection to all British film lovers of a certain age.

This cinema classic was based on a book called Jack’s Return Home, and many commentators agree contemporary British crime writing began with that novel. The influence of both book and film is strong to this day, reflected in the work of David Peace, Jake Arnott and a host of contemporary crime & noir authors. But what of the man who wrote this seminal work?

Ted Lewis is one of the most important writers you’ve never heard of. Born in Manchester in 1940, he grew up in the tough environs of post-war Humberside, attending the Hull College of Arts and Crafts before heading for London. His life described a cycle of obscurity to glamour and back to obscurity, followed by death at only 42. He sampled the bright temptations of sixties London while working in advertising, TV and films and he encountered excitement and danger in Soho drinking dens, rubbing shoulders with the ‘East End boys’ in gangland haunts. He wrote for Z Cars and had some nine books published. Alas, unable to repeat the commercial success of Get Carter, Lewis’s life fell apart, his marriage ended and he returned to Humberside and an all too early demise.

Getting Carter is a meticulously researched and riveting account of the career of a doomed genius. Long-time admirer Nick Triplow has fashioned a thorough, sympathetic and unsparing narrative. Required reading for noirists, Getting Carter will enthral and move anyone who finds irresistible the old cocktail of rags to riches to rags.

About the author

Nick Triplow is the author of the South London crime novel Frank’s Wild Years and the social history books The Women They Left Behind, Distant Water and Pattie Slappers. His acclaimed short story, ‘Face Value’,was a winner in the 2015 Northern Crime competition. Originally from London, now living in Barton upon Humber, Nick studied English and Creative Writing at Middlesex University and, in 2007, earned a distinction on Sheffield Hallam University’s MA Writing course. Since completing his biography of British noir pioneer, Ted Lewis, Nick has been working on new fiction.

It began with the laughter of children, and there it will end.

‘Drunken Morning’ – Arthur Rimbaud

Prologue

I’d exchanged emails with Mike Hodges about Jack’s Return Home – Ted Lewis’s punchy, defiant, distinctly non-metropolitan noir novel written in the twilight of the 1960s, which he’d adapted, then directed, as Get Carter in eight white-hot weeks in 1970.After the acclaimed dramas, Suspect and Rumour, made for television, it had been Hodges’ first feature film, his first adaptation, and the film that established his reputation as a great British filmmaker. For the cinema-obsessed Lewis, quite simply it had been a dream come true.

I met Mike in Hull in November 2013. I’d been invited to host the Q&A following a screening of Get Carter as part of that year’s Humber Mouth Literature Festival. Mike didn’t want to watch the film so we went to a nearby restaurant along with festival director, Shane Rhodes, the writer, Kevin Sampson, and music consultant, Charlie Galloway – Kevin and Charlie were friends of Mike’s from Liverpool, in town for the event, and Charlie had played a key role in the reissue of the Get Carter soundtrack in 1998. Over dinner, we talked about Lewis, his relationship to Hull and the Lincolnshire towns across the river where he’d lived and where Jack’s Return Home was set. We were back in time for the film’s final scenes: Jack Carter kidnapping and murdering Margaret in the grounds of Kinnear’s country house, exacting revenge on those responsible for his brother’s death, then the Fletcher brothers’ call to an anonymous hitman famously in place from the opening title scene. Mike wrote in the screenplay: The deserted beach is like the end of the world… Eric is halfway along the beach, struggling in the mud. Carter closes in on him.

From the rear of the gallery we watched Michael Caine and Ian Hendry’s chase along the slag-blackened beach of Blackhall against a grey North Sea backdrop. It looked incredible, as it always does. Mike said, ‘It’s like watching someone else’s film.’

Afterwards, a group of us walked to the pub. The wind whipped off the Humber near Victoria Quay where the ferry once moored and a 16-year-old Ted Lewis commuted between art school and his mum and dad’s home in Barton-upon-Humber. The pub, the Minerva, was his regular pre-crossing haunt. It features in his first book, All the Way Home and All the Night Through, and the 1971 novel, Plender. As the barman poured the pints, I thought about the times Lewis would have stood at the bar as we did and I wondered what he’d have made of Mike being there. I had a sense of this being the final stretch of some great circumnavigation, as if somehow I was bringing the story home. A few days later Mike emailed and asked, what was the name of that pub?

The Minerva.

Ted Lewis’s story is as much about these unfashionable, unheralded places and how they fed into his work as it is about the zeitgeist-riding moments: 50s trad jazz, the Beatles’ Yellow Submarine, the dark corners of 1960s Soho, the creation of Brit noir, Z Cars and Doctor Who. It’s also about what happens when a good-looking, jazz-loving, cinema-obsessed kid from a small town on the banks of the Humber writes his way into history then drinks his way out again.

That Lewis remains in the public consciousness at all is mainly down to a small band of dedicated admirers in Britain and America, and, of course, that Jack’s Return Home was the basis for the greatest British crime film of the 1970s, arguably of all time. Truth is, ask a room full of people to raise a hand if they’ve heard of Get Carter and you’ll witness a sea of hands. Ask, do they know the name Ted Lewis and you’ll be lucky if there are one or two. But without Lewis there is no Jack Carter, Sir Michael Caine is short of one career-defining iconic role, and the course of British crime fiction is changed forever.

When I moved to Barton-upon-Humber from London in 2001, my knowledge of Lewis extended no further than a dog-eared Get Carter paperback and a DVD of the film. For me, it was a one-way ticket to a place I’d never known. I had no idea it had been Lewis’s home town. I learned more when his name came up in interviews for a social history book I was researching in 2007. Broadly speaking there were two responses: the first, usually delivered with bluff Northern Lincolnshire dismissiveness, was that he’d left, moved to London, made and lost a fortune and returned home with his tail between his legs and died of drink. The marginally more sympathetic view was that he was a local lad who’d done well – ‘he wrote that film with Michael Caine’ – but whose boozing and philandering in later years had made him difficult to like. As one notable local told me, ‘Barton is a small town and small towns have long knives’. More than once I was reminded of the lack of any formal recognition of him in the town. The Civic Society, guardians of Barton’s heritage, pin plaques on the homes of notable local citizens. At that time Lewis had not been so honoured. I asked around. The suggestion was that he’d been too controversial a figure to warrant the tribute.

What really stirred my interest was an interview I recorded with the novelist Karen Maitland for a regional arts magazine in January, 2008. Karen’s first mediaeval crime novel, A Company of Liars, had just been published and we spoke at length about the story, its inspirations and its journey to publication. Our conversation turned to crime writers we admired, specifically Ted Lewis. Some years previously, Karen had worked as a librarian in Barton. At the time, the library kept a virtually complete collection of Lewis’s books locked away in a metal cabinet. When the county of Humberside broke up in 1996 and local libraries were placed under the authority of North Lincolnshire Council, a team from the Central Library arrived in Barton to review the stock. They told the staff to throw Lewis’s books on the tip. ‘They were old and battered,’ said Karen, ‘and they couldn’t think why we were wasting valuable cupboard space keeping out of date novels by a local author no one had ever heard of.’

To begin with, it seemed Ted Lewis had left little other than his published work and the memories of those who knew him. People entered and left his life with regularity and only a very few can claim to have been close for any length of time. Others suffer from the vagueness of memory that advances with age and the after-effects of 1960s and 70s lifestyles. Some are fiercely protective of his reputation and reject any enquiry. Others were hurt by him with the same outcome – he could, it was said, ‘turn on a sixpence’: charming, entertaining, boyishly attractive one minute; obnoxious, paranoid, self-destructive and abusive the next. For those closest to him, raking over the past is frequently a painful experience. I’ve sat down with friends, lovers, schoolmates, drinking pals, neighbours and colleagues; I’ve met with his ex-wife, his daughters, and his literary agent, Toby Eady. I’ve collected scraps of reviews and interviews from long defunct magazines. Primary sources are scarce. Verification is rarely straightforward. No formal archive or collection of correspondence exists, only a few pieces written about him for magazines and websites. Lewis didn’t keep a diary for most of his life and the majority of his papers and personal documents were destroyed after his mother’s death in 1990.

Yet the popularity of contemporary British crime fiction can be traced directly to the aesthetic he pioneered in Jack’s Return Home, found again in Plender and Jack Carter’s Law, and took to new levels of dark intensity in his final novel, GBH. That unflinching mix of tawdry underworld violence combined with an unerring eye for detail, an evocative connection with landscape and the reek of the authentically domestic, the brutal and banal, dark and psychological, and a gift for crafting language like no one who came before him, helped define the concept of present-day British noir. So why had he fallen into relative obscurity? Why, since his death in 1982, had there been no significant posthumous rediscovery? Why are his books, with the obvious exception of Get Carter, out of print in his home country?

For much of his life, Lewis exhibited the virtues and flaws of a classic noir antihero: nobility, infidelity, weakness, sickness, sex, cigarettes, love, booze and bad choices play a part. He was the star of his own film, damaged and dangerous. As a writer, he achieved an astonishing amount in a short period of time, though never enough to satisfy his expectations. His fall, when it came, was rapid. I’ve tried to fill the gaps and provide a narrative certainty, but there remain ambiguities, complexities, mysteries and half-remembered fragments which I’ve agonised over and learned to reconcile, avoiding the temptation to neaten loose ends on his behalf.

Interviewed shortly after the publication of Jack’s Return Home in 1970, he said he’d tried to ‘make it real’. The least I can do is to follow his lead and tell it straight as I’ve found it.

1

Heartache

1940–1951

Ted Lewis had a sense that something had been missing. Born on 15 January 1940 in Stretford, Manchester, among his imperfect and chaotic wartime recollections it was his father’s absence that resonated. A space which, for the first five years of his life, was dominated by his mother, Bertha, and his maternal grandmother’s matriarchal presence. In this his experiences were no different to those of countless other wartime babies and young children, their consciousness formed in an uncertain and austere time of absent fathers, air-raid warnings, rationing, bomb-damaged streets and the filtered realities of war reported each evening on the BBC news. A rare family snapshot from the period, taken while his father, Harry, was home on leave from the Royal Air Force, shows father and son together. Harry Lewis is on his haunches, tanned and healthy in the uniform of an RAF Corporal. His broad hands encircle his young son’s waist. Perhaps a little more than a year old, Edward is pale, blond and chubby-cheeked, smiling and alert in the sunshine.

By the time Harry returned home from active service for the final time in 1945, his son, christened Alfred Edward, but always known as Edward to his parents, was a fit and energetic five-year-old. Readjusting to home and family life after the war proved difficult. For a short time, Harry went back to work at the Manchester Ship Canal Company where he’d been employed as a shipbroker’s clerk before the war, but his experience had equipped him for greater responsibility. When the opportunity of a management position arose at one of the company’s subsidiary concerns across the country in Lincolnshire, he accepted.

In early September 1946, the Lewis family migrated 100 miles west to east from Manchester to North Lincolnshire. Harry Lewis took out a mortgage on 118 West Acridge, Barton-upon-Humber, a modest three-bedroom semi-detached in one of the town’s most established streets. The family moved in and Harry took up the post of manager at Elsham Quarry some ten miles away, one of several similar works peppering the landscape south of Barton which provided raw materials for building, engineering and railway industries.

The Barton that welcomed the Lewises was a small, insular market town on the south bank of the River Humber, some 25 miles from the fishing port of Grimsby to the east and 20 miles from the steel town of Scunthorpe to the west. They knew no one and the town’s few thousand inhabitants were, in the main, families which could trace their local heritage back generations. The town had built up around two distinct geographical locales: the Waterside area close to Barton Haven, a busy inlet from the River Humber, where once a ferry had connected to Hessle on the opposite bank of the river a mile and a quarter away; and Top Town, which centred on two mediaeval churches – Saint Peter’s with its Saxon tower and nearby Saint Mary’s. A few local shops and half a dozen pubs led up to the town square, home to the weekly market. Beyond its own boundaries, the town had made its name through Hopper’s bicycle factory whose machines were exported around the world; Hall’s Barton Ropery which made ropes for the Royal Navy and the Empire for 150 years; and for the manufacture of bricks and tiles – there were a number of traditional works dotted along the river’s south bank making use of Humber clay.

Across the river, accessible only by ferry from New Holland, a short train journey from Barton, or a lengthy detour inland by road, the lights of the city of Kingston upon Hull represented a distant world. The house in West Acridge gave Lewis a clear view of the river and the city beyond. After Trafford Park’s industrial grime, Barton was an idyllic setting for the Lewises. Nestling in the hillside as the landscape scoops from the outer edge of the Lincolnshire Wolds to the wooded fringes and pebbled beaches of the Humber foreshore, it would have felt clean, its broad outlook offering an uncluttered panorama of the wide river, its air unpolluted. It was a free and safe playground for the young Lewis. In his first novel, the autobiographical All the Way Home and All the Night Through, Lewis wrote his observations of Barton, describing the easy pace of living and the ordinariness of the town, concluding that although the youth complains about the claustrophobia of life, ‘hardly anyone leaves the place’.

In 1947, Lewis was enrolled at Barton County Primary School on Castledyke. Although he felt some affection for his headmaster, a quiet man called Jack Taylor, the bulk of the teaching staff were, according to childhood friend and classmate, Nick Turner, ‘formidable old spinsters’. The most draconian was Miss Crawford, a strict disciplinarian who inflicted liberal doses of corporal punishment on her young charges. Children were terrified of her. Turner remembers the consequences if Miss Crawford suspected someone had broken wind. ‘She would walk round smelling our backsides until she found the culprit and then slipper them in front of the class.’ Miss Crawford’s comeuppance came while attempting to teach the children to bunny-jump during a PE lesson when she fell on her back and had to be carried out. After the comfort of home, the sensitive Lewis was unsettled by the severity of Miss Crawford and the other teachers. They upset the sense of fairness he had come to depend on with his mother and grandmother and he withdrew, quietly shielding himself from the school’s worst excesses.

Lewis’s days at Barton County were curtailed abruptly when, in 1948, he contracted rheumatic fever. In pre-antibiotic, late-1940s Britain, cases were still fairly common, particularly among children. The disease was a major cause of death until around 1960. It would attack the heart’s mitral valve, causing it to leak, often leaving the sufferer with chronic heart problems. In addition to its effect on the heart, it was a highly debilitating illness – we know from friends that Lewis suffered severe pain in his joints. In extreme cases, rheumatic fever could lead to brain damage. Recovery was primarily dependent on the ability of the patient’s immune system to fight back and it was generally accepted that, if the sufferer kept to a minimum any potential strain on the heart, the disease would be less likely to cause lasting harm. Whilst the exact severity of Lewis’s bout of rheumatic fever isn’t known, it was certainly a grave cause for concern, serious enough for Bertha to ensure her son received complete bed rest for many months. Throughout the latter part of 1948 and into the spring of 1949, he remained at home, convalescing.

When it was suggested to John Dickinson, whose parents had become good friends of the Lewises, that he visit this young chap who was ill in bed, he found a pale boy a couple of years younger than himself, quite shy, and with a mop of blond hair, his bed littered with comic books and a pencil and paper constantly to hand. Dickinson recalls ‘he would draw all the time, always these figures of people’.

With recurrences of rheumatic fever as common as the disease itself, particularly in the years immediately after the first incidence, Harry and Bertha would have been told that another episode could cause lasting and serious, possibly fatal, damage to their son’s heart. But, as Lewis’s ninth birthday approached, Bertha dared to hope the worst was over. Thinking a birthday party would raise his spirits, she made a cake, iced with the family’s saved sugar rations. The boys who sat on the edge of the bed at his party have a clear recollection of Edward Lewis, sitting up in bed and ‘holding court’. It was as if the illness had conferred a degree of celebrity.

The friends drawn to Lewis around this time called themselves the Riverbank Boys. Barton was no different to many towns where discrete areas became territories for loosely associated groups of friends. The Riverbank Boys were hardly a gang in any contemporary sense, more a bunch of lads who played together, shared interests and made a point of looking after each other. Lewis was welcomed on board. Along with Nick Turner and Alan Dickinson, he was one of the youngest of the group that included Martin Turner, John Dickinson, Mike Shucksmith and Neil Ashley. They were Barton born and bred and came from similarly respectable families. Here, for the first time, Edward Lewis of 118 West Acridge became Ted Lewis of the Riverbank Boys after Nick and Martin Turner’s father, Arthur, decided Edward was too effeminate a name. Ted was ‘more manly’. Lewis’s friends called him Ed or Eddy. Bertha would make sandwiches for the boys and they’d sit around in her son’s room, talking, drawing, reading comics, usually with Lewis as the centre of attention. Sometimes Harry set up a hand-cranked film projector, plugged into the light socket with a bulb behind it for the boys to watch cartoon films screened against the blank wall at the foot of the bed.

In hindsight, Lewis’s rheumatic fever and the enforced period of recuperation and reading which followed, gave him a degree of knowledge and insight beyond his years. Temporarily released from the constraints of formal education, in its place, encouraged and supported by Bertha, his natural artistic ability was given licence to flourish. In the dull rhythms of convalescent days, he discovered an inner world of imagination, invention and story. Escape from the everyday came first through the wireless, particularly radio thriller serials like Dick Barton – Special Agent. Lewis was an avid listener.

He was also a keen reader of comics. While British comics of the time were, for the most part, limited to the traditional – Beano, Dandy – and boy’s own titles like Hotspur or Eagle, increasingly Lewis’s older friends were attracted to glossier American titles from the Entertaining Comics (EC) stable of crime, horror and science fiction. Crime Patrol, War Against Crime!, Vault of Horror, Tales From the Crypt, Weird Fantasy and The Haunt of Fear were captivating reads, particularly for lads raised on a diet of Desperate Dan, Biffo the Bear and old-fashioned heroes and villains of Empire. EC comics were no ordinary adventures. These were stories of violent revenge, punishment, guilt and retribution. Death’s Double Cross, Under Cover and Snapshot of Death and countless stories like them delivered a jolt to Lewis’s pre-teenage imagination. He was enthusiastic about the vivid colours and graphic narratives, the more horrific the better. The byline of his and Nick Turner’s favourite comic featured a gleefully sadistic character hunting roadkill in dark city streets spouting the mantra: ‘Blood and guts all over the street, and me without a spoon to eat.’

Retrospectively viewed as a highpoint in pop culture in the period before concerns about juvenile delinquency in the United States prompted senate hearings to neuter their alleged impact on American youth, early EC comics have a parallel in the pre-censorship film industry of the early 1930s. Eventually, they would be codified and sanitised. They were bold, entertaining and featured tough heroes, deviant victims, good stories, sharp dialogue and eye-catching artwork. Some stories, like those of artist Johnny Craig, were naturalistic and had moral undertones. Others were gratuitously violent or overtly sexual. Lewis was enthralled by torture scenes, double-crosses in shadowy alleyways, gangsters in fedoras and hard-bitten detectives. They also began to influence the way he wrote, finding expression in the pages of his drawings. His comic strips and fictional characters were more colourful and they now had speech balloons.

An American comic in Barton in the early 1950s would have seemed a wildly exotic item and a prized possession. Although Bertha enthusiastically provided her son with whatever he needed to keep him happy and occupied, it is unlikely she would have been able to find, or would necessarily have approved of, the comics had she been aware of their content. Buying comics was a challenge for Lewis and the other boys. Often they were handed on by the older members of the Riverbank Boys, those with pocket money, part-time jobs or paper rounds. It was said they could be bought from sailors who came through the docks at Hull and Immingham. Martin Turner remembers buying them from a novelty shop in Cleethorpes – a thriving holiday resort and popular destination for daytrippers an hour or so from Barton on the train.

Lewis was absent from school for several months. Illness had left him physically fragile. It had also deepened the already close bond between mother and son. In later years, he told one friend of a game they played in which Bertha would ask, ‘Who are you going to marry?’ To which he would answer, ‘You, mummy’. Bertha was determined he should be back to full health before returning to school. On warm afternoons, she set a chair in front of the house and allowed him to sit outside. Friends remember passing on their way home from school, stopping to talk to the boy swathed in blankets. He became something of a curiosity, the illness marking him out as different. When they asked why he wasn’t at school he told them he had ‘heartache’.

A school class photo, taken in the summer of 1949, shows a group of children, smart, but perhaps a little dowdy in hand-me-downs or the best that clothing coupons could buy. Lewis sits at the front, distinct, with his longish blond fringe swept across his forehead. He looks healthy, smiling. By the time he left Barton County in the summer of 1951, a promisingly bright boy, perhaps a little more fragile than most and extremely shy, the strict regimen of schooldays had sown the seeds of a quiet rebellion. As he regained strength, Lewis spent more time with friends, exploring the landscape and absorbing his surroundings: the River Humber, its windswept shores, rolling grey-brown tides, hidden nooks, disused tile and brickworks, jetties, broad bays and river-borne traffic were fertile grounds for the imagination. Here in the riverside wilderness, he found freedom from illness and a place to play.

2

Voice of America

1951–1956

The Barton Grammar school which opened its gates to Lewis in September 1951 had been founded, like so many others, on principles borrowed from the public school system. Conservative by instinct and ethos, it sought to produce young men and women of sound learning, high academic achievement and traditional values. Established in 1931, the school had done much to elevate the town’s standing. Its teachers were among the most respected members of the community, their status as educators and moral guardians unquestioned. Entrance was by no means a formality. Earning a place at ‘the grammar’ was an achievement, an indicator of aspiration for the children of Barton’s working class and lower middle class families. For Lewis’s friends, Nick and Martin Turner, John and Alan Dickinson, Mike Shucksmith and Barbara Hewson – all former pupils – schooldays are recalled with mixed feelings. For some, Barton Grammar was the passport to opportunity their parents had worked for, fought for, and on which they’d staked their children’s futures; but it could also be intolerant of any pupil who did not, or could not, fit the mould socially and academically.

The school population, mainly from Barton and nearby villages, had been increasing year on year. By the time Lewis arrived, student numbers had risen to around 300. The proximity of the war and its after effects continued to shape the way people lived. Clothes were only available on coupons and food was still subject to rationing. Boys bragged of their shrapnel collections and told stories of the bomber crews from RAF Kirmington and the godlike American fighter pilots who had frequented local pubs – the RAF station at Goxhill had been transferred to the US 8th and 9th Air Force in 1942. Sixth former John Grimbleby would describe how he had found the impression of a German airman in the earth in a field outside Barton, the victim of a failed parachute. Luftwaffe raiders had routinely used moonlight reflecting off the Humber to navigate into Hull, turning home over the south bank. Barton people remembered the drone of bombers night after night when it had seemed as though the entire waterfront and city of Hull was ablaze. John and Alan Dickinson’s father, a wartime fireman, told stories of how his fire crew had been strafed by a German fighter at New Holland quayside – most credit went to the ‘heroic’ Salvation Army officer who continued to serve tea throughout the raid. At school, teachers returning from the services had resumed their careers, readjusting to civilian life in the classroom. Physical education and geography teacher Jack Baker still wore his khaki battledress jacket to classes, just as he had for his job interview.

The school’s headmaster, Norman Goddard, was a modern languages scholar. Hard-featured, with cold grey eyes, a Mozart specialist and strict disciplinarian, Goddard had established a fearsome reputation on his arrival in the spring of 1951. Martin Turner remembers that ‘within a week, he had tamed the school’. Boys were expected to lift their caps to senior teachers; minor uniform, timekeeping and homework indiscretions were routinely punished, with one hundred lines the standard penalty. At the conclusion of each morning’s assembly, Goddard took his place in front of the stage and read the list of names of those he wished to see. ‘If he wanted to see you at lunchtime,’ says Nick Turner, ‘it was a ticking off. If it was break time, you might be able to talk your way out of it. But if he wanted to see you straight after assembly, you were in big trouble.’ Goddard caned boys across the hand, a punishment from which girls were exempt, but which seemed only to make his verbal and psychological admonishment of them more severe. Teachers used the threat of being made to stand under the clock opposite the headmaster’s office to deter bad behaviour. It came with an ever present fear of interrogation should the door open and Goddard demand to know why you were there. Nick Turner remembers, ‘Say you’d been talking in class, he’d ask, “Why were you talking?” That was his thing, he’d say, “Why? Why? Why? Why?” again and again until you were an abject mess and you’d say, “Because I’m stupid, because I’m a fool.” He’d wear you down with the same question over and over.’ When the rumour circulated that Goddard had spent the war working for British Intelligence, interrogating captured German prisoners, no one had difficulty believing it.

In September 1951, Edward Lewis arrived in his new navy and light blue quartered cap, stiff navy blue wool blazer, polished shoes, striped tie and grey flannel trousers. Still finding his feet a few days into the new term, he was leaning against a wall near the boys’ entrance to the playing field, hands in pockets, hair uncombed, tie loose around his shirt collar. Taking exception to this apparently insolent attitude from one of his boys, particularly a first former, Goddard walked purposely towards him. Lewis, 1M wasn’t it? After a sharp ticking off, Goddard slapped him hard across the face. The shock of the assault caused Lewis to wet himself. Goddard continued with his lunchtime inspection, leaving the new boy to clean himself up.

For the pupils, many of whom had recently arrived from village primary schools, none of whom had witnessed anything quite like it, this was a salutary lesson. They might have been used to corporal punishment – in common with most lads, Lewis had been ‘walloped’ by his father for misdemeanours in the past and there was the memory of Miss Crawford – but this was different. Goddard had decided to make an example of him. News spread through the school that ‘Ed Lewis had pissed himself’. Inevitably, for the next few days he ran the gauntlet of snide comments. For the most part, his friends recall that these did not last and he was treated with sympathy; others, you suspect, were less kind-hearted. A new boy in a new school, he was humiliated and now vulnerable, knowing the incident was in reserve for the opponent in any argument. While Harry and Bertha may have disapproved, they weren’t about to challenge their son’s new headmaster and the episode was to remain with Lewis for the rest of his life. In his 1975 novel, The Rabbit, he included a graphic retelling of the story of the headmaster’s slap, the sickening sensation of wetting himself in public and locking himself in the toilets until everyone had gone home.

Lewis’s introduction to the school could hardly have been worse. The quiet distaste for authority he’d begun to nurture at Barton County grew deeper and he withdrew further. As others fell into line, conforming to the everyday rigours of school life, the injustices – real and perceived – hurt him deeply. Unfortunately, his place in the modern language form 1M brought him into regular contact with Goddard who would take the class for German lessons. Here Goddard reserved special treatment for boys not paying attention, pulling up the desk lid at the same time as sharply pushing the boy’s head down. Inevitably, there were bloody noses. For entertainment one Friday afternoon, he sat them to attention on PE benches in the school hall and played an LP of Mozart’s Eine Kleine Nachtmusik. In the verbal examination that followed, Nick Turner remembers, he asked, ‘Had we heard this part or that? And if not, why weren’t we listening?’ For Lewis, always nervous in Goddard’s presence, lessons like these were unbearable.

Reading Enid Brice’s book, A Country Grammar School Remembered, which tells the story of the school, there are former pupils who consider Goddard embodied a necessarily ‘strict but fair’ brand of school discipline. It was hardly unheard of for 1950s schoolteachers to be authoritarian and corporal punishment was commonplace, but this seems different. Years later, on being told he had terrified one former pupil, Goddard said, ‘Ah, but it worked, didn’t it?’ Mike Shucksmith thinks otherwise. ‘There were tough teachers, and you respected them. I got it a couple of times for being a silly bugger, but Goddard was a shit. I hated him.’ Interviewed by the Manchester Evening News in 1970, Lewis would recall an occasion he’d been seen eating fish and chips in the street and was publicly rebuked by Goddard for ‘eating comestibles out of a paper bag’. It was not the kind of thing a Barton Grammar School boy ought to do. Lewis warmed to his theme, ‘If you weren’t a machine storing up maths, French, and anything moving away from the arts, they’d frown on you. I’ve written three novels and the first, about school, was rejected. The publisher I took it to at the time considered it libellous.’

Life outside the school gates offered plenty of distractions. In July 1952, the Lewises moved from West Acridge to a larger property at nearby 46 Westfield Road, a few doors down from the Shucksmiths. The new house, bought for £1,500, had previously belonged to a local doctor, Charles Hawthorn. It had a sizeable basement and attic and, in the front room, stood a newly bought upright piano on which Lewis began having lessons with a local teacher, Harold Johnson. Outside there was a small piece of adjoining land with an orchard and a few chickens. In the garden, which had a small, deep dip-pond filled with foul-smelling water, Lewis and his friends were soon making the most of the space, experimenting with homemade artillery, firing rockets along a length of drainpipe through an old dustbin lid. Health and safety was of the ‘duck when you see one coming’ variety. Past the pond and through the orchard, there was a collection of outbuildings in various states of repair, accessible via an old carriage drive from West Acridge.

With the extra space in the new house, Bertha’s mother, Mrs Shaw, came to live with the family on a permanent basis. It was not a comfortable arrangement for Harry. In truth, as Lewis eased into adolescence, Harry was rarely around. A nine-hour day, six-day week at the quarry kept him from home. Travelling to work in the lorry that picked up and dropped off workers in Barton station yard, the boys would see him walking home of an evening, covered in a film of white limestone dust, visibly exhausted, trilby tilted on the back of his head. John Dickinson remembers him as a tall, dour, deep-voiced Lancastrian with a dry sense of humour, calling wearily, ‘It’s alright for you lads, you ought to be doing a bit of this digging in the garden.’ Lewis would invariably give him some chat back.

For Harry, the new house marked a change in status, an aspirational step towards something more than respectable working class. He accepted an invitation to join the local masonic lodge and, in doing so, became one of a group of influential local businessmen with a keen – some have said controlling – interest in the town’s affairs. Able to favourably interpret or circumvent the rules as suited their interests, there were rumours of good turns given and received, and planning consents for business premises in the town granted without question. By all accounts, Lewis found the masons and their arcane customs faintly ridiculous. He would refer to ‘that lot up there’, goading Harry about his visits to the lodge on Brigg Road, and threatening to read and expose the secrets in his mysterious masonic handbook.

Westfield Road became a home from home for the Riverbank Boys. Bertha provided an endless supply of tea and would also turn a blind eye if they smoked. She and Harry were heavy smokers and the kitchen was routinely a fug of cigarette smoke. Lewis and Nick Turner had been 12 years old when they bought their first pack of 10 Robin cigarettes from Mr Rowley’s shop at the corner of Newport and Fleetgate and made their way to the riverbank, hiding in one of the disused brickworks kilns to smoke all 10. At school, a smokers’ circle congregated behind the groundsman’s hut at break times, which led to a running battle with the school groundsman, Mr Stamp, who frequently threatened to report the ‘little bastards’, but never did.

The easy availability of cigarettes was due, in part, to local shopkeeper, Bill Doughty, who sold them in singles from his shop in Market Lane. He kept a room at the back of his shop for his boys to smoke in and there were usually one or two dragging away. He also sold lemonade in a penny or twopenny glass and after each boy had finished drinking would take out a dirty rag and wipe the glass for the next.

Around this time, Lewis became ‘Lew’ to his friends. No one can quite remember how it came about, other than it sounded more American, like the names he’d heard in films. Cigarettes became a prop, adding to the image he was cultivating, the careworn private eye with a cigarette clamped between his lips. He adopted the smoking styles of screen stars he admired. Often he would smoke in the two-storey stable block beyond the orchard with its horseboxes and hayloft. It became the boys’ de facto headquarters and Lewis christened it ‘Kexby Hall’. It allowed him a superficial independence whilst remaining under Bertha’s watchful eye, although the carriage path from West Acridge meant a surreptitious entrance and exit could be virtually assured. Kexby Hall also housed Lewis’s collection of pornographic magazines. Not, as it turned out, the safest place to store them. On a slow day at the quarry, Harry sent workmen to the house to clean the stable block. By the time Lewis found out, it was too late to retrieve the magazines. He was horrified, later telling Martin Turner, ‘Have you ever stood and shivered at the awful realisation that there’s something you really didn’t want anybody else to see?’ Petrified the workmen would find the magazines and tell his father, he said, ‘I just froze.’ If they were found and if Harry was told, Lewis never ascertained.

A mile or so outside Barton town centre, close to the river, is the site of what was once the Adamant Cement Works. Monuments of the river’s industrial past reveal themselves; remains of buildings and kilns, a brick border underfoot, remind you that this riverside waste ground was once a working factory. If you break off the main path and work your way through the bracken and brambles until it opens to the foreshore, you’ll come across an expanse of stony beach and the wide grey river. There you’ll find cement set in the shape of the sacks, the sacking long since rotted away, which marks the place where barges would dock to load cement and tiles to be transported upriver to Goole, or across to Hull docks and beyond.

The ‘old cements’ and ‘pebbly beach’ were important places for Lewis and his friends. They spent countless days, weekends and school holidays setting up camp with the Turner brothers’ ex-army pup tents pitched end to end, a groundsheet and a couple of blankets. They cooked beans, sausages, eggs and bacon on an open fire. In season there were wild strawberries and blackberries. Water for a brew came from a nearby spring. Away from prying eyes, says John Dickinson, they would ‘go wild’. Just how wild is open to conjecture. When the old wooden jetty, known as Ferriby Goss, burned down, a rumour circulated that the fire had been started by the Riverbank Boys. The surviving boys, now in their 70s, are saying nothing. Evidence remains in remnants of weatherworn wooden piles on the riverbank a few hundred yards west of the Humber Bridge. On desolate winter mornings when the fog is at its thickest, the wooden spars and pilings of the wrecked jetty stick out from the sucking mud like Normandy tank traps. On those mornings it feels like a haunted place.

In All the Way Home and All the Night Through, Victor Graves describes the roofless and decaying works with their peeling paint and plaster, loose bricks tumbling. He speaks of their darkness and mystery, concluding that they were ‘holy places’, sanctuary from long days at grammar school, where he and his friends could truly be themselves. A collection of black and white snapshots captures what now seems like a last blast of childhood lived out in roughhouse re-enactments at Ferriby Cliff or the old cements: Lewis and Neil Ashley’s re-creation of Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing’s final ascent of Everest in 1953; a horseplay battle in progress – the life and death manhunt for the meanest hombre in town; and a group photo of Lewis, the boys, and Jane Guymer and Pat Parkin, two Barton girls invited for the evening.

For a group of energetic adolescent boys used to making their own amusement, the Humber bank, the old brickworks and its surrounding wilderness held limitless ways to have a good time. Here they played endless games of hunter and hunted and made hand grenades from damp clay moulded around bangers, with the fuse left exposed. Lines scored in the clay as it dried made them look like Mills Bombs. ‘You’d light the fuse, wait, then throw the grenade,’ says Nick Turner. High quantities of gunpowder made for impressive explosions.

The only rules were those they agreed amongst themselves. There were occasional fallings-out. Once, when Lewis came across E LEWIS in chalk graffiti on the wall of one of the deserted tileworks buildings, he was incensed, shouting, ‘Fucking hell, everyone knows me, I’m gonna get the blame for this.’ Mike Shucksmith picked up the chalk, adding a ‘T’ and ‘H’ in front of the ‘E’. Eventually the graffiti read THE LEWISHAM ART CLUB and Lewis was placated. Neil Ashley, suffering with a headache, was tormented by Shucksmith chasing him up and down the foreshore, banging on a dustbin lid with a rock. Nick Turner remembers he and Lewis would stand at the river’s edge, close to the navigation channel on the south bank, and taunt barge skippers in cod pirate accents, ‘What be yer cargo? Be it shit?’

Time was immaterial. One summer morning Neil Ashley was due to cycle down as soon as he’d finished his early morning paper round. At camp, the others got up, had breakfast and ‘buggered about’ for a few hours and were finishing lunch when Ashley arrived on his bike. They asked where he’d been. ‘Doing me job,’ he said. They asked why he hadn’t joined them for the morning. He said, ‘What d’you mean? It’s only nine o’clock.’ When darkness fell, the boys told ghost stories by the light of a hurricane lamp, taking turns to ‘scare the pants’ off the youngest, usually Alan Dickinson. Sometimes Gandi Smith from nearby South Ferriby visited and the Barton boys made up horrific tales, then watched Gandi cycle home in terror, his bike’s rear light deviating erratically across the riverbank path until it disappeared into the darkness.

Pinning an exact time and place to Lewis’s first taste of beer takes you to those days on the riverbank. Older than Lewis by a couple of years, Martin Turner, Michael Tink and John Dickinson were served in local pubs from the age of sixteen or seventeen. For camping weekends, the closest pub was the Nelthorpe Arms in South Ferriby. From there they would buy bottles of beer, smuggling them out to the more obviously underage Lewis, Nick Turner and Alan Dickinson waiting in the car park. Or they’d take the beer back to camp. At The George in Barton, landlady Lila Harrison would serve the older boys and Lewis drank pints of bitter bought for him. He had no great capacity for alcohol and after three or four pints would make his excuses, go outside, throw it all up and then carry on drinking. Other times, the boys went to village pubs in nearby Winteringham or Elsham where they weren’t so well known. Later, there were holidays at Butlins, one illustrated in a photograph of an obviously sloshed Lewis, suited, booted and grinning from ear to ear as he leans on Martin Turner’s shoulder. He looks no older than fourteen or fifteen. Friends recall he began to use beer as an antidote to his usual shyness. He was more sociable and less self-conscious, but after a couple of pints, could become uncharacteristically argumentative.

On the corner of the High Street and Fleetgate, stood the Star cinema; the Oxford cinema was nearby in Newport Street. Both were a few minutes’ walk from Westfield Road, or a smart gallop if you’d seen a western. From the age of nine or ten, Lewis had adored the thrill of an afternoon at the pictures. His first heroes were the cowboys: Roy Rogers, Gene Autry and John Wayne. Walking home, the boys would keep the stories going, excitedly imagining scene after scene. Sometimes a tethered horse grazing in a field on the way home found itself playing a role in re-enactments as they took turns riding bareback, shooting imaginary renegades.

Of the two Barton cinemas, the Star had earned a reputation as something of a fleapit; its down at heel quality wasn’t helped by frequent projector malfunctions. The manager, ‘a pompous little man’, would take to the stage to offer apologies to a tirade of catcalls from the boys in the stalls. But with two performances on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday, beginning with a cartoon or a short – the Three Stooges were firm favourites – followed by a ten minute Pathé News Reel and a main feature; then a change of programme for Thursday, Friday and Saturday, the pictures were a cheap diversion from school and homework. A sixpenny stalls seat in the Star wasn’t much of a dent in Lewis’s pocket money. At every programme change, he would take his seat in the darkened auditorium, revelling in outsider stories of the American frontier, imagining himself as John Wayne in The Searchers or James Stewart in Bend of the River. He loved gangster films, the more hard-hitting the better, favouring flawed tough guys like Lee Marvin in The Big Heat or The Wild One over the clean-cut, smooth mannered heroes who dominated the posters. Lewis preferred the kind of men for whom violence was second nature, capable of sadistically crushing weaker characters without a second thought.

Lee Marvin had walked out of Lee Strasberg’s Actors’ Studio in 1950, reputedly with a ‘fuck you’ to the venerable acting coach. He’d already established himself as Lewis’s favourite film actor when Edward Dein’s Shack Out on 101 showed at the Star.Shack was one of a series of low budget red-peril paranoia B-movies. For Lewis, the politics was a marginal consideration. Marvin played ‘Slob’, a wisecracking short-order cook in a rundown roadhouse on the eponymous Route 101. Violent, mouthy, vindictive, revealed to be acting as a courier in the sale of state secrets from a nearby government establishment to an unnamed foreign power, Marvin steals the film entirely and bags the best lines – ‘It’s a good job I’m not wired, you could push me around like a vacuum cleaner’. In the week it played, Lewis saw Shack Out on 101 enough times to memorise much of Slob’s dialogue. In the film’s climactic scene, to avoid discovery, Slob roughs up all-American girl and Shack waitress, Kotty, played by Terry Moore. He shoves her head through a window, then makes to stab her with a cook’s knife, before meeting his match on the business end of a harpoon gun. Only then do his treacherous secrets come tumbling out.

Taking his lead from dialogue like Marvin’s, Lewis was acquiring his own way with a one-liner. In a tender moment from one long-forgotten film, as the hero cradled a dying woman in his arms, Nick Turner remembers a voice calling out, ‘Fuck her while she’s warm!’ Smart throwaways and sharp-tongued putdowns became part of his repertoire and a useful teenage defence mechanism.

Lewis’s interest in cinema bordered on obsession. He bought Picturegoer magazine and shared a subscription to Films and Filming with John Dickinson. He immersed himself in the minutiae of filmspeak, memorising names and functions of those involved in the production as the credits rolled, staying in his seat until the final frame, delaying the moment he would have to rejoin the real world. Afterwards, it was as if he needed to carry the stories with him from the cinema. Talking about them kept them real and alive.

Once the early Saturday house had finished around eight o’clock, the boys would walk up the hill to Westfield Road where Bertha waited with tea and sandwiches. She’d sit with them in the kitchen, giggling at in-jokes and stories about how they’d got on with girls. Some nights they played three card brag for pennies and ha’pennies at the kitchen table. Lewis might be persuaded to play the piano, improvising or playing tunes from memory. Mostly they went upstairs to the attic sitting room to smoke and go over that evening’s film with Lewis leading long conversations and pulling the plot to pieces, dismantling the action scenes, glorying in the violence. ‘This was the best bit’ or ‘this was the cruellest’.

In his room at Westfield Road, film books, magazines and annuals competed for shelf space alongside the crime and horror comics and detective novels. Gathering detailed knowledge of the directors, writers, actors and designers – the people who made films – was just as important as knowing the stars. To most people they were remote figures, names and functions scrolling past as you tipped your seat and collected your coat, but for Lewis, by the time Shack showed at the Star, they represented his burning desire to work in film.

The second of Barton’s cinemas, the Oxford, was marginally more sophisticated than the Star. It had an upstairs balcony with double seats for couples and a small foyer of its own, attended by an usherette, usually the formidable Mrs Haddock. A couple of ancient sofas with zigzag patterned upholstery and a standard lamp gave the foyer the feel of a slightly dowdy 1930s lounge. Afforded a little more discretion, the Oxford was the place Lewis began to take girls.

The shy, good-looking blond boy who had a way with words and could make you laugh then cut you dead had no shortage of offers to hold hands. Lewis had a succession of on-off girlfriends, most of them adolescent affairs over almost as soon as they began. He rarely broke off one relationship before assuring himself the next girl was waiting in line. Sometimes the chase was all that mattered. The affections and attentions of girls seemed to fulfil his need for reassurance. With friends he might not have lacked confidence, but alone or with girls, he could be deeply insecure. He was certainly self-conscious about his teeth, which he considered imperfect. He developed the habit of keeping his mouth closed when he laughed. It didn’t seem to bother anyone else, other than the time he had a cold and a closed-mouth sneeze landed projectile snot on the sweater of the girl he was chatting up.

This phlegmatic attitude to girls changed when he met Jean Walker. She was a year or two older than Lewis. Her brother, Michael, had been on the fringes of the Riverbank Boys’ friendship group for a while. On visits to the Walkers’ house when their parents were absent, Jean and Lewis would disappear upstairs where, according to one friend, ‘She taught Ted all he got to know about sex’. A group photograph taken at what looks to be a Christmas party shows Lewis sitting front and centre, every inch the young adult in suit, shirt and tie, flanked by his friend, Barbara Hewson, on his right and Jean on his left. He and Jean angle their bodies towards each other, somehow separating themselves from the others, as if in their own photograph.