2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

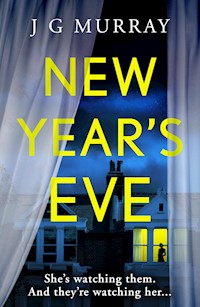

New Year's resolution: Murder... When Hayley and Ethan move into Palace Gardens, they feel their luck has finally changed. No more run-down flats in dodgy areas. But behind the exterior of this beautiful Victorian house, things are less than picture-perfect, and the tight-knit community is unwelcoming. When Hayley befriends the woman next door, no-one is pleased. Least of all the man from upstairs. The one who watches them all from behind his window. Then they receive an invite for a New Year's Eve party. But what seems like a friendly gesture, proves to be anything but... READERS LOVE NEW YEAR'S EVE! 'An excellent read... I loved this book from start to end.' Manju, NetGalley review 'So dark and edgy... Truly gripping and wonderfully written.' Karena, Netgalley 'A cracking read, fast-paced, full of surprises and twists - brilliant!' Joanne, NetGalley

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

J G Murray grew up in Cornwall and, after a spell selling chocolates in Brussels, worked as an English teacher in Bangkok. Murray won the 2018 Deviant Minds Crime Thriller Prize for his debut The Bridal Party. He lives and writes in Hove.

Also by J G Murray

The Bridal Party

Published in e-book in Great Britain in 2020 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © J G Murray, 2020

The moral right of J G Murray to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 011 8

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

Chapter One

New Year’s Eve

‘Are you ready?’

Every part of me says no. Of course I’m not ready.

There’s no way I could be.

Ethan sees my expression and laughs. It is part mockery, part sympathy.

‘This is a party we’re going to, right?’ he teases. ‘By the look on your face, you’d think we were headed to a funeral.’

I shake my head, not in the mood to respond. We’re in the hall, preparing to leave. Our New Year’s Eve best on. I’ve managed to convince Ethan to put on a shirt and blazer he normally uses for work, and I’m in a black dress with sequins that I’ve never worn before. Ethan has even bought a bottle of what we guessed was good-quality Prosecco. Bizarrely, he’s placed it by the front door: it sits there like a pet waiting to be let out.

We still don’t quite know what to do with such luxuries – they don’t belong in our world yet, much as we want them to.

Ethan slips my coat off the hanger and offers it to me. I don’t take it.

‘I’m still not sure about this, Ethan,’ I tell him.

He exhales in a way that is just enough to hint at his irritation. ‘Hayley, this was your idea. When I think about how many times you’ve talked about the neighbours, how you wish we got on with them …’

I get it. I’ve been pacing around the flat for hours, unable to make a decision. I’ve even changed out of my outfit, deciding to abandon the evening altogether, only to put it back on again minutes later. I know how infuriating it must be: for him, none of this is a big deal. It’s just a party. We’re popping down to the flat downstairs for a drink, then heading out to meet our actual friends in town.

But then he doesn’t know. He hasn’t put his ear to the walls of this building and heard the blood pumping through its veins. He hasn’t met the cold looks of Flat B; the flashes of resentment from Flat A. Nobody stares at him from their window in Flat F whenever he goes outside. No one has hurt him the way they have hurt me.

Ethan steps forward. He towers over me; he is tall, sinewy. There is a leanness to him, from his buzz cut to his wiry limbs: although he eats and drinks whatever he wants, his body never gains an ounce of fat. He runs a thumb along my cheek and holds my chin like I’m an infant. His face looms close, his dark eyes finding mine. I catch the scent of his deodorant.

‘Let’s just take a deep breath and do it,’ he murmurs. ‘The sooner we go, the sooner it will be over. And then we can get out of here and have an actual good time.’

I don’t answer; just trail a finger down his arm, thinking it over.

He continues, very quietly now. Intimate. ‘Or not. We can blow it off. I don’t care. But it’s decision time.’

I glance up at that face, so close and familiar. At those eyes.

I take the coat out of his hand and begin to put it on. ‘No, you’re right,’ I say. ‘Let’s get it over with.’

He looks at me for a moment, as if deciphering whether I really mean it.

‘All right then.’ He nods. His eyes flicker; a glimmer of regret. As if maybe he wanted me to call the whole thing off.

But now it’s settled. Without another word, we go through the rituals: we gather our coats, check our phones, wallets and keys. Ethan grabs the bottle of Prosecco; he holds it awkwardly by its neck, like he’s going to wield it as some sort of weapon. I think of telling him that he’s probably shaking it too much by holding it that way, but hold my tongue. I can hardly claim to be an expert.

We are both doing our best to avoid tension and disagreement. I have, after all, just come back from staying at my father’s house after we agreed to spend some time apart. We are acting as if everything is normal, that this is a night like any other. I wonder when that will stop, and when we will have the conversation that determines our future.

With our coats and shoes on, we look at each other one last time. Ethan gives a little shrug. I’m not quite sure what it means, but I know that I don’t like it. Until we talk things over properly, every gesture and word is loaded with subtext.

He shuffles out of the front door and holds it open behind him, inviting me to leave. I take a final look at our flat; the hall is a stretch of comfort and familiarity, underlined with our coats, shoes and bags. I still think of it as new, even though we’ve lived here for the best part of a year. But that doesn’t stop it from being ours; a little pocket of us in the alien world of our apartment block.

I switch off the light, and the hallway disappears into gloom.

In all the apartment blocks we’ve lived in before, the stairs and entrance were just extensions of the street. They were dirty places, filled with dust, takeaway leaflets and letters addressed to past residents. No one took ownership of such areas; they were merely passageways into our homes.

Palace Gardens is different.

The walls are spotless white; the stairs carpeted and soft, so much so that you can go up and down in ghostly silence. The banisters gleam, the wood dusted and polished regularly. I don’t know who cleans the stairs, nor when they do it. It’s all part of the clockwork mechanics of a building I still can’t pretend to understand.

As we head down the stairs, I glance at the mark on the wall. I made it when scraping a guitar case against it on the day we moved in, and I can’t help but look at it every time I pass by. It’s a smear of grey against white, like a forensic thumbprint. Every time I see it, I want to cast a furtive glance up and down the stairs, as if someone is ready to launch out of their flat and accuse me of blemishing the property.

Ethan doesn’t pay any attention to the mark. He doesn’t tend to notice such things.

At the bottom of the steps is the entrance hall. There is a wooden pigeonhole assigned to each flat; another first for us when we moved in. Opposite is an oval mirror circled by a copper-coloured frame in the shape of a knotted rope.

I cast a quick glance at myself as I leave: beneath my thick coat, the sequins of my dress gleam. I wonder if it will be too eye-catching for the neighbours; they always seem to be impossibly well put together, elegant but simple.

Ethan doesn’t wait for me. He hunches a little, getting ready for the cold outside, and charges out of the front door. Freezing air floods into the hall; my skin tingles with winter. I glance one last time at the sight of my face framed in copper knots, then head into the chill.

There’s always a strange energy at the beginning of New Year’s Eve. The world is poised, holding its breath. It’s the only evening of the year when you know that everyone is awake, readying themselves. The restlessness can be felt in the air. A gust of wind surges across the road once we emerge from the building, rattling the bushes. The trees that line our street stretch this way and that, grasping and fumbling at each other like drunken lovers. Their leafless arms fracture a night sky coloured deep purple, as close to black as it gets in London.

With our heads hunched into our coats, Ethan and I make our way around the gravel drive, heading to the side entrance of the ground-floor flat. The cold quickens our pace, the ground crunching underfoot as we pass a row of gleaming cars. Inconveniently large for city living, the vehicles are a demonstration of wealth that belittles our own financial status. Since moving here, I’ve made it a habit to scoff at the petrol-guzzling vehicles whenever I can. Ethan never joins in with me.

We circle round the building, and an automatic light sears on, turning the gravel to gold at our feet as we approach the door to Flat A. The fact that it has a separate entrance is a sign of the property’s importance and superiority.

I don’t have time to gather myself before Ethan steps forward and rings the doorbell. There’s light beyond a layer of frosted glass, and I can hear voices inside. Soon we will be among them. The neighbours.

My throat tightens a little.

Ethan and I step back from the door, the way you do when you don’t really know the person about to open it. He takes my hand, gives it a squeeze, but it is perfunctory. He doesn’t want to be holding hands when the door opens. Affection, for him, is only demonstrated in private.

I wish he’d hold me a few seconds longer.

It’s only a short moment before the frosted glass darkens with the shape of someone behind it. The lock clicks, and the door opens.

Silhouetted by the light inside, a figure gazes out at us.

I can already feel my insides protesting in discomfort. It’s George, the owner of Flat A. He is the richest man in Palace Gardens; with the ground floor flat spilling onto the gardens under our balconies, his property is inarguably the most valuable and extravagant.

He nods at us. It is less a greeting and more an acknowledgement of our presence. He is a short, stocky man who has lost all his hair. As if to make up for it, his limbs bulge with personal-trainer bulk. His outfit of a shirt, waistcoat and chinos is, as always, well judged. He is just the right side of flamboyant, the image of someone I tend to think of as fashionable, but only because his looks communicate wealth and good living.

Last time we met, he shouted at me. Threatened me. Hurt me.

The tension between us is still there. I can see it in his features. A smile that looks more like a grimace. Eyes open slightly too wide, belying pent-up excitement. An eagerness for something to begin.

‘Finally,’ he breathes. ‘You’re here.’

When we are led inside, it is all smiles and handshakes.

George takes the bottle of Prosecco out of Ethan’s hands. ‘I’ll put it in the fridge,’ he says, as if that suffices as thanks. Then we are in the main kitchen and living room, surrounded by our neighbours, flutes fizzing with champagne in our hands.

Ethan hasn’t met many of the people in Palace Gardens; he goes around shaking hands and introducing himself. He’s always known how to work a room, to make his presence felt. But he has rarely been in company such as this. I wonder whether his boisterousness will work its charm here as it does everywhere else.

I follow him round the party. I’m more familiar with the neighbours and know all of them by name. There’s Teresa and Joshua from Flat B; the neighbour I call Staring Harold from the floor above us; and, of course, Beatrice from down the hall. She is the only one who doesn’t conform to what I like to think of as the Palace Gardens type: wealthy, proud and suspicious.

In the driveway, in the hall, the neighbours tend to be quiet and judgemental. Now, though, it seems they have all decided to adopt different personas. Gathered around an island counter in a spacious kitchen on New Year’s Eve, you’d never suspect the secrets they’re hiding. You’d never know there are people in this room who hate and loathe me, so much so that they would banish me from the building if they could. Here, everyone seems perfectly decent; they laugh at each other’s jokes and enquire about each other’s families.

Two-faced, the lot of them.

I feel the first sting of resentment, as though a false note has been played inside me. It is always this way with the neighbours in Palace Gardens. I oscillate between contempt and fear, unable to decide whether I am beneath them or better than them – or both.

In total, there are seven of us at the party. We don’t even begin to fill the room, which seems to expand with every glance. Last time I was here was a blur; now I have time to take in my surroundings.

The kitchen gives onto the living room: it is sparse, with every object set in its correct place. The television is large, but everything else is tasteful. There is none of the usual London-flat cramming; in fact, the lack of clutter is downright disarming, giving the place the air of a showroom. It is a completely alien world from our own home, just a short walk away. The room is bordered by French doors giving onto the stretch of grass outside, the lawn gleaming yellow from the lights within. It is hard to believe it is the same garden I can see from our balcony upstairs.

A photo on the mantelpiece catches my eye. It is one of the few personal touches in the flat, and it stands out as a result. At first I don’t recognise George in the picture. He has his arm around the shoulder of another man, and I’m taken aback by the clear display of affection. He has only ever treated me with scowling resentment, and even to the other neighbours he has always seemed civil rather than affectionate. The features of the smiling, warm-hearted man in the photograph feels like they belong to a different person.

It is clear that the two men are related: they have the same pattern of balding hair, the same strong brow, the same beard shading their jaw. But apart from the broad strokes, they look completely different: the brother, the famous Curtis I’ve heard about, has pale skin and sunken eyes. A worried look is buried under his smile, contrasting with the composure and authority of his brother.

‘You’re just in time,’ Staring Harold says, bringing me out of my reverie. I would recognise the thick-cream softness of his voice anywhere. He is both the elder statesman of Palace Gardens, and its embodiment; he, more than anyone, is able to mask his cold judgements with pleasantries and good manners.

Everyone murmurs in agreement. They always do when Harold has spoken.

‘Oh yeah?’ I reply. I don’t know what else to say; I feel like I haven’t uttered a word since I’ve walked in, and am still adjusting to the presence of my neighbours.

‘In time for what?’ asks Ethan, looking around, sipping at his champagne. He is trying to sound enthusiastic, but his question comes across as blunt. I wonder whether the importance of etiquette is holding him back. Everyone else has their drink delicately poised between their fingers; he holds his champagne like a mug of tea.

‘In time for the game,’ Beatrice says, looking at me with a forced smile. She is the one in the group I know best, and the only neighbour with whom I have a rapport. The smile is, I imagine, supposed to be encouraging. I have not seen her made up before; she is wearing a loose orange dress and a mismatching shawl, and lipstick that only reminds me how thin her lips are. Her hair, curly at the best of times, is a mangle of brown, scribbled unevenly into the air. It’s like she wanted to wear something special but was distracted while she got ready.

Maybe she was in a rush because of Zander, I think. I glance around for her child; he is not here. Who on earth is babysitting him?

‘A game?’ Ethan says. He gestures in my direction. ‘This one’s good at games. She’ll love it.’

The focus shifts to me. What games do I like? a few of them ask in a chorus. As if they care. With the Palace Gardens lot, any subject of conversation deemed safe and uncontroversial is immediately pounced upon and milked for all it’s worth.

Ones that I play with people I like and trust, I think to myself. It’s true: I enjoy playing board games. I’ve played some with Zander, Beatrice’s son. In fact, our entire relationship is founded on playing Mouse Trap, Guess Who? and Uno.

But playing a game here, in this environment? With people I barely know, and who dislike me?

I can’t think of anything worse.

Before I can respond, George reappears from somewhere with strips of paper and pens. He does not seem to realise that he is interrupting a conversation. He is manic; a host who is just a little overeager, unable to let the party breathe.

After passing everything out, he takes a breath, and looks over at Staring Harold, who nods as if giving him permission to continue.

‘This is a New Year’s game to see how well we know each other here in Palace Gardens,’ George declares. ‘It’s time to see who knows the community best.’ He throws a look in my direction. ‘This might be a little difficult for you. You’ll have to guess, I suppose.’

Was that thinly veiled criticism? I wonder. Or – even worse – is this game designed to make Ethan and me feel excluded? I wouldn’t put it past George. In fact I wouldn’t put it past anyone in this room, apart from Beatrice.

Ethan and I exchange a glance. Whatever the reason for the game, it will be embarrassing for us. Embarrassing because we won’t be any good at it, and because of what it will force us to reveal about ourselves.

I am starting to lose my nervousness; it is slowly being replaced by anger, gnawing away at my good will.

‘Hayley, I’m relying on you for this one,’ Ethan says, picking up his drink for a too-large glug of champagne.

‘Don’t worry,’ says Beatrice to me. ‘It’s just a bit of fun.’

Her voice trembles a little. Is she upset? I wonder. Her eyes seem bloodshot, and she is on edge. Is it because she’s apart from Zander? Or is she overly concerned about me? It’s hard to tell: she always seems to be on the verge of a nervous breakdown, no matter what the situation.

I put on a neutral face and nod back at her.

With everyone supplied with paper and pen, George, oblivious once more to the conversation, announces the rules.

‘It’s called the resolution game,’ he announces. ‘Everyone writes down their New Year’s resolution on a piece of paper and puts it in a hat. Whoever manages to guess who wrote which resolution wins a point, and the person with the most points wins the game.’

There’s a murmur of anticipation.

‘I haven’t decided on my resolution yet,’ says Teresa in mock protest. She is all calmness and warmth, and even though she is heavily pregnant, she still has that yoga-perfected posture and skin as unblemished as a Palace Gardens wall. Of course you haven’t, I think. It’s hard when you’re so bloody perfect.

‘I don’t need one. I’m flawless as I am!’ grins her husband, Joshua. He is pleased with himself at the joke. The others laugh as if they’ve never heard it before, and another current of hate runs through me. Satisfied at the reaction of the room, he grins. How can a man be so utterly pleased with his own mediocrity? I wonder. I force myself to forget about it, to gulp down the anger like a pill. I’m here to make friends, I tell myself.

To make things better.

‘Right,’ says George, when the laughter has died down. He grins. Again, it looks pained, like he has swallowed something foul. ‘Write down your resolutions,’ he orders.

He is rushing the game. Trying to get it over with. I am momentarily distracted, wondering why he is so eager for us to play at all.

Everyone settles down to write and the conversation dies. The music, the kind of lifeless background jazz I can’t bear, fills the room with its inadequacy. I tap the paper with my pen, unable to think of anything. I must have had dozens of ideas over the past few months, but I can’t remember any of them.

Apart from the very one I can’t say, of course.

Unearth the secret of Palace Gardens.

I look over at Ethan, who shrugs. I know he hasn’t thought of a resolution. He doesn’t agree with them. Ethan only self-reflects in jumps and starts, at moments of crisis and change or not at all. He will write something banal, I think. Like Get back to playing football. He’ll put down anything to get this over with: I can imagine that he’s just as uncomfortable as I am, in his own way.

‘Okay, fold your papers twice and put them in the hat,’ declares George. It feels like we’ve barely had any time at all: I haven’t written a thing.

I scribble down Take better care of balcony and put it into the hat George is passing round. Of course, it’s an expensive-looking fedora; even a silly game such as this is a chance to boast. To me, it’s like something only a TV character would wear.

Everyone else throws their paper in and looks around with anticipation. Putting my pen down, I am more than happy to have my glass back in my hand. I take a large swig; I’ve already knocked back most of my flute.

The first one to take a paper out is Beatrice. There is a moment or two of silence as she unfolds the slip, turns it the right way up and holds it at a distance; she is long-sighted, and normally wears glasses. I notice that her hands are shaking a little. Why is she so nervous? Again I think of how odd it is that Zander isn’t here.

‘Learn to scuba dive,’ she reads out finally. She pulls a puzzled expression and looks around, inspecting people’s reactions like a schoolteacher. It is forced; a pantomime. She is struggling to mask her emotions, just as I am.

Comments go back and forth as the guests start to discuss who might have written the resolution, and Ethan and I are asked for our opinion. We answer, truthfully, that we have no idea. Ethan has gone silent; he tends to either dominate a conversation or not speak at all.

‘I think it must be Joshua,’ Beatrice decides, giving the paper to him. ‘Is this after you went to the Seychelles in the summer? You said it gave you a taste for it, didn’t you?’

‘Guilty!’ he chuckles.

A short conversation follows as everyone coos admiringly over Teresa and Joshua’s holiday travels.

‘Don’t even bloody know where the Seychelles are,’ says Ethan. ‘Near Worthing, aren’t they?’ The joke falls flat; the Palace Gardens residents smile politely and then return to discussing the holiday.

As Joshua’s resolution has been picked, he is selected to make the next guess. He takes out a paper, unfolds it and reads out: ‘Take better care of balcony.’

There’s a weight in my stomach; I glance furtively around the room. Silence. They are stumped, trying to ascribe the words to each other. The resolution doesn’t fit. It’s not the Seychelles. It’s not scuba diving. It is, quite simply, not Palace Gardens enough.

‘I know,’ George says, that grimace smile painted all over him. ‘I think it must be Hayley.’

‘Oh. Why?’ asks Beatrice.

‘When I’m in the garden, I have a view of everyone’s balcony. And there is one that stands out. It’s a bit … unkempt, shall we say.’

I grit my teeth. Yes, there are a bunch of dirty flowerpots with dead plants on our balcony. Filled with energy when I first moved in, I tried to make it look pleasant. But, not having had any experience with gardens or flowers, I quickly lost my enthusiasm and stopped bothering.

The words sting. Everything George has said so far just reiterates what he thinks of us: that we are outsiders, unworthy of Palace Gardens. I’d hoped that the invitation to this party was a clue that he’d forgiven me. Now I can see that it was the opposite: an opportunity to humiliate me and see how I’d react.

I throw another glance at Ethan; he is stony-faced. Perhaps he doesn’t register how rude this is. I will have to talk it through with him later and make him understand. It’s all right for him; he’s never going to be accused of not taking care of the flowers. Not in the backwards bubble of Palace Gardens.

But perhaps I won’t have to: I can detect a glimmer of anger in him, in the clenching of his jaw. He might not know about flowerpots, but he can detect the hostility in George’s tone.

Emboldened, I look George in the face, and smile like it’s a retaliation. ‘Guilty,’ I say, parroting Joshua earlier. This eases the situation; people appreciate the repetition, as if a fun new tradition has been established. Joshua in particular seems pleased that his phrase has been reprised. He holds his gut as he laughs.

I keep my gaze fixed on George.

‘One point to me, then,’ says George. ‘And now it’s your turn to read out a resolution, Hayley.’

He walks up to me and offers the hat. Our eyes are still fixed on one another, as though we are in a one-upmanship competition. As though we are playing a different game altogether.

There is something wrong here, with both Beatrice and George. I can sense it. There is a secret they’re not sharing; an anticipation. It’s as if they are just biding their time, the whole party a preamble to something else.

I finish my drink. If George is going to be like this, at least I’m going to enjoy his expensive champagne. I put my glass on the counter and turn back towards him. I take my time before dipping my hand into the hat, slowing the game down to an excruciating standstill. Conversations die out and the music fails to mask the absence of chatter.

Finally I take a slip. George steps back so that the guests form a circle once more. I straighten out the note and read what’s written.

It takes me a moment to fully realise what the word in front of me says. My throat catches in shock; I can’t speak.

‘What is it?’ someone asks.

But I still can’t answer. It’s like my lungs have ceased to function.

I feel a hand on my back. Ethan.

‘Hayley?’ he enquires. I look up from the strip of paper to a line of staring Palace Gardens faces.

I finally mange to force the words out.

‘It just says Murder,’ I say.

Chapter Two

28 May

The first time I stepped into the world of Palace Gardens is seared into my memory.

I was just finishing a guitar lesson at a student’s house, placing my instrument back into its case, when my phone chimed, announcing a text. It was from Ethan.

I think I’ve found it! Can you come and check it out now?

I’d forgotten that he’d been visiting properties that afternoon: my head was still full of scales and chords, octaves and keys.

Found what? I sent back.

His reply was just one word. Home.

I felt an excitement and a charge, all coming from that word. Ethan wasn’t much for emotional phone communications: for his excitement to spill out in text form was an indication of just how thrilled he was. There was another string of messages, urging me to come quickly and giving me the address. The estate agent was keen to close the deal; there were, apparently, other couples who were also interested in renting the flat, and if we wanted it, we would have to sign a contract quickly. It was a by-the-book trick, employed by estate agents everywhere to goad us into accepting. We’d seen enough places by now to know that.

But it didn’t make the trick any less effective.

I didn’t think. I whirled out of my student’s house, barely even remembering to take my pay. I clattered along pavements and down escalators, and launched into a Tube carriage, wielding my guitar case clumsily and almost battering commuters with it. I hadn’t thought about where I was going: I’d simply typed the address into Citymapper and allowed it to lead me blindly into the Underground.

It was only when I started to get closer to my destination that I realised where I was going, and how long the journey was taking. The carriage started to become more spacious, shedding masses of people at every stop. People started to sit more comfortably, reading their papers, briefcases tucked between legs.

I tended never to be without music; I hated crowds and needed my noise-cancelling headphones to help me ignore the world around me. With the rush, and with my mind churning with thoughts, however, I hadn’t even bothered to fish them out. And now here was a new experience. A Tube journey without stress or hustle; without an armpit to one side of my face and a sharp elbow in another. A journey where I didn’t need to close my eyes, shut out the world and focus on the melodies hushed into my ears. A journey where I had space to breathe.

There were seats available, but I remained standing. I don’t entirely know why; perhaps it was because I was still adrenalised by the rush. Perhaps I just wasn’t used to it.

I was still a bus ride away from the flat when I emerged from the Tube. The bus clipped around Highgate Wood, and I was aware of the blur of imagery around me: a valley of woodland, rising and falling by the side of the road, full of families, dog walkers, runners. Facing the woods were lines of expensive-looking houses with front porches and drives that belonged to one family and one family alone.

I got off at Muswell Hill, a name that meant next to nothing to me. I’d never been to this area; I’d never had friends or students who lived here.

I half ran through the grand streets; they were wide and seemed even wider because of the curiously long gaps between cars at the sides. Parking spaces, normally an anomaly in London, yawned between the vehicles. I took in my surroundings, but never fully acknowledged them; they were just images, flitting through my vision.

It was only when I saw Ethan waving at me from the pavement that my mind fully took in why I was there.

I’d been acting like I’d been heading to a lesson. But that wasn’t the case. I was here because my boyfriend had told me he’d found somewhere for us to live. Ethan, in a slim-fit white shirt with a loosened blue tie dangling carelessly from his neck, was grinning, beckoning to me. An estate agent, grey-suited and phone in hand, looked at me curiously as I rushed towards him, guitar case bashing against my knees.

As I approached, I caught sight of the building in front of which they were standing. Amidst the bushes I got snatches of a grand entrance, wide windows and Victorian arches. My immediate thought was that it couldn’t possibly be true – that Ethan couldn’t think we were actually going to live here.

And yet there he was, looking at me, then back at the house, beaming helplessly. It was my favourite smile in the whole world: the cocky, childish grin that he broke into whenever he felt like we were getting away with something.

We musicians talk sometimes of the fact that when you pluck at a string of an instrument, the corresponding string on the neighbouring instrument will reverberate a little too, joining in on the same note. That’s how I liked to think of Ethan and me. As two instruments picking up each other’s reverberations. Whenever he grinned like that, I knew I was incapable of doing anything else but grinning straight back.

We must have looked like loons to the estate agent, rushing towards each other, laughing like we’d won the lottery.

But we didn’t care.

I crashed straight into his arms, and he picked me up, guitar and all, and set me down facing the building. The name, Palace Gardens, was written on a gold plaque at its gates.

‘Is this it?’ I breathed. ‘Can we afford it?’

‘You bet we can,’ came the answer, very close to my ear.

The estate agent stepped forward and introduced himself. He had a bunch of keys in one hand and shook mine with the other.

His watch, and the keys, caught the sun at the same time, the gleam flaring my vision. I blinked as I heard his words.

‘Welcome to Palace Gardens,’ he said.

Chapter Three

22 June

We moved in during a hot spell in June. It was a Sunday.

I spent most of the day in a daze.

Palace Gardens was every bit as grand and impressive as the first time I’d seen it. As the van entered the drive, and the building loomed above me with its facade of dark-red brick and white windows, I was dazzled all over again. It was the kind of place that belonged to others; the kind of place that adorned the windows of estate agents with a price tag that made me want to either laugh or scream.

The idea that we were going to live there was enough to make me shake my head in disbelief.

No matter how many times I climbed up and down its steps, no matter how much of the apartment filled with our familiar mess, the feeling never left me. I couldn’t quite accept the reality that Palace Gardens would be my new home. The whole building was quiet, and we didn’t meet a soul. But every time I passed a door, I wondered who lived behind it, and what their lives were like. I wondered how their experiences compared to my own.

Ethan was excited; he grinned throughout the day and made silly jokes. He bowed in exaggerated fashion when we crossed each other on the stairs, as if we were now the lord and lady of the manor. He referred to the man we’d hired to drive us over in his van as our chauffeur. But I was too distracted to join in.

At one point he poked me to get my attention. I was standing in front of the built-in wardrobes in our bedroom, wondering how I would ever have enough clothes to fill the gaping spaces. ‘Happy?’ he asked, checking on me.

‘It’s huge,’ I breathed. It was as close to an answer as I could give in my stupor.

It was only when I took up my final piece of luggage – my guitar case – that I managed to emerge from my bewilderment. As I was climbing to our floor, my legs starting to strain with the exertion of carrying our belongings up the flights of stairs, I heard a scraping sound.

I turned and saw that the case had knocked into the perfect whitewashed walls and left a dark smudge. It was small, no longer than a finger. But it stood out nonetheless: a blot of ink on a clean page.

My first instinct, for some reason, was to look around to check whether anyone had seen me. But that was absurd. Clearly the other residents were capable of living in the building without blemishing its walls.

Everyone would know that their new neighbours were the culprits.

I rubbed the mark with my thumb, but it didn’t come off. It only smeared a little. I couldn’t tell whether it was better or worse that way.

So I left it, and hoped that no one would mention it.

Moving day was a blur of stress and exertion, of too-empty rooms and sandwiches eaten while perched on cardboard boxes. We ate an absent-minded dinner at a local chippy, the kitchen still too much of a mess for us to navigate.

The day after, however, was a Monday, and I remember it perfectly.

Ethan had gone to work, and I found myself alone in the flat for the first time. I remember that it was hot: the light and heat were searing through the windows, and unpacking was causing me to sweat.

But most of all, I remember the novelty of silence.

Our old flat had been next to a main road, and I’d always assumed that living in London meant that one had to put up with a constant buzz of traffic, punctuated by the occasional shrieks of teenagers. Here, however, the silence seemed to permeate the air. Someone once told me that places like Muswell Hill used to be where Victorians would go to escape the smog of central London, and that felt right to me. I did not really feel as if I was still in the city here: I was divorced from it, floating above it.

The silence dominated Palace Gardens so much that even the floor beneath my feet was soundless. I was barefoot, enjoying squashing my toes into the carpet. I’d never liked carpets. They were quick to stain and difficult to wash, and I preferred a floor that could be swept, the chance to make things look new with a few quick movements. But here, the carpet was clean, like a blank sheet. Whoever had lived here before had been immaculate – intimidatingly so.

After stacking all the new plates and bowls in a kitchen cupboard, I paused to take a breath. Even with all the windows open, and wearing just shorts and a dirty tank top, I felt unbearably hot. There was nowhere to rest; just more boxes to shift and unpack. The flat barely had any furniture, and my surroundings were the physical representation of a to-do list.

I picked up a dining chair and took it outside onto the baking slabs of the balcony floor. We didn’t have a table or chairs for the outside yet: it was empty. Placing the chair down, I went back inside to fish out a bag of weed from one of my rucksacks.

In our last neighbourhood, I’d had a regular dealer; God knows where I was going to find one here in Muswell Hill. Ethan had decided that we were now above such things, but I’d never quite agreed. In any case, he wasn’t due back from work for hours, and I was free to smoke to my heart’s content.

With my Ray-Bans perched on my nose, I sat in the sun to roll my joint. Once it was lit, I put my feet on the balustrade and took a long drag, savouring the taste and the sensation in my throat. Beneath me, a well-kept garden was bordered by trees and bushes, which shone green with health. The world was still, the only movement the sweet-smelling trails of smoke easing through my fingers.

I was able to appreciate the calm of Palace Gardens, and it felt like bliss. A tune came to my lips, like a speaker freshly plugged into an instrument. The melody soothed out of me.

Clamping the joint in the corner of my mouth, I went to my guitar case in the bedroom and clicked it open. I took my battered guitar back out onto the balcony, cradled it in my lap and strummed. It was out of tune, so I spent a few minutes puffing, humming while I plucked at the strings. I tried out some basic chords; a G and a D. Pinched away at some harmonics. Soon it was there; every note in its place, filling up the hollow of the guitar’s body. The joint dangled at my lips, almost forgotten now. I took the tune I had hummed and put it to chords, creating a melody.

Perched awkwardly on the dining chair, I sang and played and smoked. The sun was burning hot: if I wasn’t careful, I’d get my usual blush of sunburn on my cheeks. But I didn’t care; all I wanted to do was keep playing until I could tease out the rest of the song. Life had been so hectic in the build-up to the move that my song-writing had taken a back seat. Here, even with stacks of boxes in the living room behind me, I felt enough freedom to open myself up, to let music flow out.

I’d once read that places have a chord and a note that suits them best. I’d never quite believed it, romantic though the idea was. But here, I could get a sense of what that might mean. The vibrations from my old guitar felt like they belonged in the quiet of this balcony, in this summer air. In Palace Gardens.

I played the melody out and sang. Not any words in particular, just placeholders for what would eventually become lyrics. I got through one chord progression, which then led to another. Within minutes, I had both a verse and a chorus. I smiled and allowed myself to pause for a moment; to enjoy the sun on my brow, the trees painting my vision a luscious shade of emerald. I indulged in imagining my next gig and hearing the applause that would follow this new song.

Then something caught my eye in the garden below, and I looked down.

There was a man looking right back up at me.

He’d emerged from a shed at the end of the garden, a bag in hand. He was wearing shorts, deck shoes and an open shirt; simple but expensive-looking clothes that made him seem taller than he actually was. He appeared to have stopped in his tracks just in order to stare at me; he was craning his neck to observe me, his brow furrowed.

‘Hi,’ I called down to him, trying to ignore the intensity of his gaze. ‘I’m Hayley. I just moved in.’

At first he didn’t reply. He scanned me and my balcony, his eyes pausing for a moment on the joint between my lips.

I waited for his response, suddenly very aware of myself. His look was difficult to read, but I thought I could discern suspicion – confusion, even – at my presence.

‘Hi,’ he said, not offering his own name. There was no warmth to it, the greeting an unconscious reaction to my own.

Without uttering another word, he turned away and strode into the building beneath me.

I pondered what kind of first impression I’d made with my dirty tank top, bare feet on the balustrade and joint dangling from my lips. It hadn’t been ideal, but hardly enough to warrant such a rude reaction, surely?

My mind, which had been so clear just a moment ago, immediately became clouded. I couldn’t shake the vision of the man looking at me in that judgemental way. I tried to dismiss my thoughts; I picked up my guitar again and attempted to return to the song, but it didn’t sound right any more. The moment was lost.

I put my guitar back in its case, stubbed out the joint and got back to unpacking.

Chapter Four

23 June

I lifted my glass of wine. ‘To our first Palace Gardens meal,’ I said.

Ethan raised his bottle of beer, and repeated: ‘To our first Palace Gardens meal.’

We held each other’s gaze and clinked glasses. After the rush of moving day and the dinner of chips hastily grabbed in the middle of unpacking, we’d decided that the previous night did not count: this was to be the first official meal in our new apartment. There were still boxes in every room, but it didn’t matter: our new life together in Muswell Hill started now.

‘This,’ Ethan motioned towards the food in front of him, ‘looks awesome.’

I’d made a meal, removed as many boxes from the vicinity of the table as I could, and even found some candles to light.

‘Well, it’s something, I guess,’ I answered. I’d hardly prepared a gourmet feast. It was a stir-fry with udon noodles, a classic dish that we tended to make out of laziness or lack of ideas. I could tell that he was overdoing the praise, but I appreciated his words all the same. Ethan was excellent at gauging my needs; at saying the right thing at the right time.

‘Didn’t have much time to look around,’ I said. ‘But I noticed that there are butchers and fishmongers around Muswell Hill.’

‘Really?’ He started to eat, twirling a mass of noodles around his fork. ‘Didn’t used to have that in the old neighbourhood. Wasn’t enough room between the fried chicken shops.’

‘Maybe we could experiment a little, get some fresh meat or fish every once in a while.’

‘Right on. Although I bet it’s bloody expensive.’

‘I just meant when we have people over or whatever.’

Ethan took my hand. It was supposed to be a romantic gesture, but it was mistimed. Having just pitchforked an over-large clump of noodles into his mouth, some rogue strands dangled from his lips.

I burst out laughing. ‘Classy,’ I commented.

He held his hand up in apology, finishing his mouthful. ‘I’m sure this is how people round here eat, right?’ he joked.

‘Oh yeah. I’m sure they always dribble half their food down their shirts.’

‘You say that, but aren’t you supposed to eat some posh food with a bib? Like, lobster or something?’ He put on his mock-posh accent, which sounded like Jane Austen narrated by a strangled parrot: ‘It all sounds pretty bloody barbaric to me, wouldn’t you say, what?’

I rolled my eyes but couldn’t quite suppress my laughter.

He grasped my hand again and started once more in earnest. ‘What I was going to say is that I don’t want us to get into the habit of me depending on you. I don’t like the idea of you being a fifties housewife, going to the butcher’s and the baker’s and preparing dinner for when I get home. I want to do my bit.’