Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

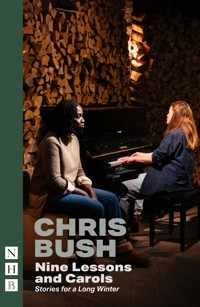

A play about connection and isolation, forged during the Covid pandemic, exploring what we hold on to in troubled times. Chris Bush's play Nine Lessons and Carols: Stories for a Long Winter, with songs by Maimuna Memon, was first staged at the Almeida Theatre, London, in 2020, directed by Rebecca Frecknall. 'A reminder of the power of theatre and our need for it' - Telegraph 'Tender and embracing, Nine Lessons and Carols leaves you with the glow that only comes from a true sense of shared experience' - The Stage

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 80

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CHRIS BUSH

Nine Lessons and Carols

with an Introduction by the author

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Dedication

Introduction

Original Production

Characters

Nine Lessons and Carols

About the Author

Copyright and Performing Rights Information

For Roni, of course

Introduction

These plays were first performed in the three-year period between autumn 2018 and autumn 2021, a period which, I think we can all agree, was generally fairly quiet and uneventful on a global scale. They don’t represent the beginning of my writing career, but do mark the point where I was increasingly able to make the work I wanted to, pursue the ideas I found most interesting, and stretch my theatrical muscles in new and exciting directions.

I wrote my first play when I was thirteen. It is not included in this volume. I sincerely hope that no one will ever have to read it again. Even so, I knew pretty much from that point that I wanted to write theatre for a living, and started to plan accordingly. Growing up in Sheffield, theatre was never presented to me as something rarefied or inaccessible. The Crucible remains the best theatre anywhere on the planet, and there was nowhere better to fall in love with the form. I studied at the University of York, primarily because of the reputation of its drama society, and took my first show to the Edinburgh Fringe in 2006 (which spectacularly sank without a trace). I fared far better the following year with the none-too-subtle TONY! The Blair Musical, and graduated in 2007 fully convinced I was skyrocketing towards a glittering career. Then nothing happened for about five years.

Actually, that’s not quite true. I was writing lots, and continually sending scripts off into the void (occasionally trying to stage them myself, which was never the best idea), while working whatever minimum-wage/zero-hour/low-commitment jobs would pay my rent. Towards the end of 2012 I received a year-long attachment to the Crucible through the Pearson Playwrights’ Scheme (now the Peggy Ramsay/Film4 Awards), and a two-month residency at the National Theatre Studio. It was while on attachment in Sheffield that I was commissioned to write my first piece of large-scale community theatre (The Shef field Mysteries in 2014, directed by Daniel Evans), something that has formed a huge part of my practice over the last decade. It’s complete madness that big community plays are often entrusted to less-experienced, emerging writers, seeing as they’re just about the most technically challenging work there is, but I’m not complaining. These vast logistical undertakings taught me a huge amount about storytelling and practical theatre-making, as well as about community and purpose and audiences and collective ownership of work, and this grounding has informed just about everything I’ve written since.

So, by the time we reach Steel, the first play in this volume, I’d been writing theatre on and off for eighteen years. I think this is worth mentioning as a useful counter-narrative to all the overnight successes who get their debuts staged at the Royal Court before they can legally drink, and fame and fortune seems to follow immediately. 2018 was a real breakthrough year for me, and felt like it had been a long time coming. I made The Changing Room for National Theatre Connections, The Assassination of Katie Hopkins for Theatr Clwyd, my adaptation of Pericles in the Olivier (my first NT Public Acts project), and Steel for the Crucible Theatre Studio (now the Tanya Moiseiwitsch Playhouse). By this point I’d written three large-scale community shows for the Crucible, and was looking for a new challenge. Somehow, I managed to corner incoming Artistic Director Robert Hastie within his first couple of weeks on the job, and pitched him an ambitious political epic spanning several decades. He agreed to commission it just so long as I could make it work with two actors, and Steel was the result. I knew Rebecca Frecknall from some shared time together at the National Theatre Studio, and was delighted when she agreed to direct. Having made so many big and complex shows in the run-up to Steel, I found the whole process a joy, and a fairly straightforward prospect, although I remember at the time Rebecca saying it was the most stressful thing she’d ever done. In a two-hander there really is nowhere to hide, no bells and whistles or theatrical dazzle camouflage to distract an audience from anything that doesn’t quite work. Fortunately we were blessed with a superb cast and phenomenal team, and of course now everybody knows what a genius Frecks is. The themes contained within – those of power, female agency, northern identity, a sense of place and belonging, and good people fighting a flawed system – can be found throughout much of my work.

2019 was another full year, with the inaugural production of Standing at the Sky’s Edge in Sheffield and The Last Noël for Attic Theatre. I was also busy working on a string of other projects, including Faustus: That Damned Woman for Headlong, which was commissioned in late 2018. I had been wanting to put my own spin on the Faust myth for years, but initially struggled to get going. I got it into my head that I wasn’t just writing a play this time, but proper literature – this was to be big, serious, grown-up work for an internationally renowned company, and it had to be just right. The self-imposed pressure to create something great – or even worse, important – is a terrible thing for a first draft. But I persevered, first developing the script with the brilliant Amy Hodge, and later with Caroline Byrne once she was attached to direct. We opened at the Lyric Hammersmith in January 2020, before embarking on a small UK tour. Far beyond anything else I’d written, I was convinced this was the show that would make my career.

Then the world fell apart.

Faustus was playing at the Bristol Old Vic in March 2020 when theatres across the country closed. By chance, I ended up catching what would be the penultimate performance of the run, and I’m so glad I did. Faustus wasn’t an easy make and took some critical flak along the way, never quite making the splash in London that I’d hoped for. Still, by this point in the tour it felt like it had really found its feet. Jodie McNee and Danny Lee Wynter were firing on all cylinders, and the whole production had gained the confidence and propulsion it always needed. The Bristol Old Vic is an exceptionally beautiful theatre, which wears the scars of its history for all to see. Sometimes plays reveal their true nature to you very late in the day. My Faustus is about morality, religion, patriarchy, ambition, gender, vengeance, and many other things besides, but sitting in that ancient auditorium that afternoon, it fully struck me how much the piece is about disease – not just the great plague of 1665 in which the action starts, but sickness and medicine and mortality are at its core. Because theatre is a live art form, our understanding of a text will always be influenced by the circumstances under which we experience it. At a recent student revival I attended, themes of AI and technology felt particularly prevalent. In future productions, should I be fortunate enough to have them, who knows what will leap to the fore? Still, on that strange day in March, this was a show about plague. On the train back to London I got a call from one of the producers – the theatres were closing, but this was just a temporary measure. With a bit of luck we’d be off for no longer than a fortnight, and able to finish the run in Leeds as planned. It turns out everything took a little longer.

I’m not sure I’ve made a ‘normal’ show since Covid, by which I mean a show not in some way impacted, curtailed, postponed, reimagined or somehow interfered with as a result of the pandemic. Maybe that just is what ‘normal’ looks like now. In October 2020, while everything was still extraordinarily uncertain, I got a call from Rebecca Frecknall to make a show with her for the Almeida. A week later we met actors, and a week after that we were in rehearsals for what became Nine Lessons and Carols: Stories for a Long Winter