Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Wissenschaft und neue Technologien

- Sprache: Englisch

Time travel is a familiar theme of science fiction, but is it really possible? Surprisingly, time travel is not forbidden by the laws of physics - and John Gribbin argues that if it is not impossible then it must be possible. Gribbin brilliantly illustrates the possibilities of time travel by comparing familiar themes from science fiction with their real-world scientific counterparts, including Einstein's theories of relativity, black holes, quantum physics, and the multiverse, illuminated by examples from the fictional tales of Robert Heinlein, Larry Niven, Carl Sagan and others. The result is an entertaining guide to some deep mysteries of the Universe which may leave you wondering whether time actually passes at all, and if it does, whether we are moving forwards or backwards. A must-read for science fiction fans and anyone intrigued by deep science.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 182

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

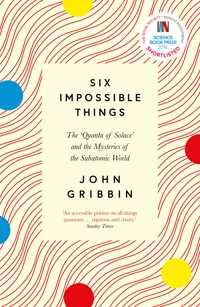

Praise for Six Impossible Things

‘[A]n accessible primer on all things quantum … rigorous and chatty.’

Sunday Times

‘Gribbin has inspired generations with his popular science writing, and this, his latest offering, is a compact and delightful summary of the main contenders for a true interpretation of quantum mechanics. … If you’ve never puzzled over what our most successful scientific theory means, or even if you have and want to know what the latest thinking is, this new book will bring you up to speed faster than a collapsing wave function.’

Jim Al-Khalili

‘Gribbin gives us a feast of precision and clarity, with a phenomenal amount of information for such a compact space. It’s a TARDIS of popular science books, and I loved it. … This could well be the best piece of writing this grand master of British popular science has ever produced, condensing as it does many years of pondering the nature of quantum physics into a compact form.’

Brian Clegg, popularscience.co.uk

‘Elegant and accessible … Highly recommended for students of the sciences and fans of science fiction, as well as for anyone who is curious to understand the strange world of quantum physics.’

Forbes

Praise for Seven Pillars of Science

‘[In] the last couple of years we have seen a string of books that pack bags of science in a digestible form into a small space. John Gribbin has already proved himself a master of this approach with his Six Impossible Things, and he’s done it again … [Seven Pillars of Science is] light, to the point and hugely informative. … It packs in the science, tells an intriguing story and is beautifully packaged.’

Brian Clegg, popularscience.co.uk

Praise for Eight Improbable Possibilities

‘We loved this book … deeply thought provoking and a book that we want to share with as many people as possible.’

Irish Tech News

‘[Gribbin] deftly joins the dots to reveal a bigger picture that is even more awe-inspiring than the sum of its parts.’

Physics World

‘A fascinating journey into the world of scientific oddities and improbabilities.’

Lily Pagano, Reaction

‘Gribbin casts a wide net and displays his breadth of knowledge in packing a lot into each chapter … a brief read, but one that may inspire readers to dig deeper.’

Giles Sparrow, BBC Sky at Night Magazine

NINE MUSINGS ON TIME

Science Fiction, Science Fact and the Truth About Time Travel

JOHN GRIBBIN

CONTENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

John Gribbin’s numerous bestselling books include In Search of Schrödinger’s Cat, The Universe: A Biography, 13.8: The Quest to Find the True Age of the Universe and the Theory of Everything, and Out of the Shadow of a Giant: How Newton Stood on the Shoulders of Hooke and Halley.

His most recent book is Eight Improbable Possibilities: The Mystery of the Moon, and Other Implausible Scientific Truths. His earlier title, Six Impossible Things: The ‘Quanta of Solace’ and the Mysteries of the Subatomic World, was shortlisted for the Royal Society Insight Investment Science Book Prize for 2019.

He is an Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the University of Sussex, and was described as ‘one of the finest and most prolific writers of popular science around’ by the Spectator.

For Teresa, who understands the importance of time

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks once again to the University of Sussex for continuing to provide facilities including a warm place to work and plenty of coffee. My interest in the nature of time and time travel goes back many years, and has led to fruitful discussions with many friends and colleagues, too numerous to list here, but I would particularly like to mention Paul Davies from the world of science and Douglas Adams from the world of fiction. The rest of you know who you are!

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Astounding magazine cover

Ourania

H.G. Wells

Arthur Eddington

Gregory Benford

Newton’s prisms experiment

Isaac Asimov

Frank Tipler

Jodie Foster in Contact

Fred Hoyle

Julian Barbour

David Deutsch

Robert Heinlein

Buddy Holly

xv‘Come thou, let us begin with the Muses who gladden the great spirit of their father Zeus in Olympus with their songs, telling of things that are and that shall be and that were aforetime.’

Hesiod, in his Theogony

‘It is owing to their wonder that men both now begin and at first began to philosophize; they wondered originally at the obvious difficulties, then advanced little by little and stated difficulties about the greater matters, e.g. about the phenomena of the moon and those of the sun and of the stars, and about the genesis of the universe.’

Aristotle, Metaphysics

PREFACE

Musing on the Muses

I have been fascinated by time travel since I started reading – I was going to say, since I started reading science fiction, but some of my earliest reading memories revolve around Jules Verne (Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea) and H.G. Wells (The Time Machine), quickly followed by anything and everything by Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov, with monthly doses of Astounding magazine,* under the editorship of John W. Campbell, long before it metamorphosed into Analog. One of the great things about Astounding was that each issue included a fact article, describing genuine scientific discoveries that were of a kind to appeal to a science fiction fan. Verne, Wells, Clarke and Asimov, of course, were all authors who included a healthy dose of real science in their stories. They became, along with Astounding, my personal muses, the inspiration for my career writing about science that sometimes sounds like fiction, and (eventually) fiction based on science – a highlight of my career was when I first had a story published in Analog, although by then Campbell was no longer with us.

xviii

Astounding magazine cover

Penny Publications/Dell Magazines

xixOver the course of that career, I have often returned to the themes of time and time travel, and it seems like a good idea to pull the threads together in one tapestry. This is not a reprint collection, but a reworking of highlights, some of which may be familiar to you and others which may come as a surprise, with new material as well as updating. The whole, I hope, is greater than the sum of its parts, and I have enjoyed writing it almost as much as I enjoyed seeing my first short story in Analog.

The idea of my personal five muses gave me a pattern for the project. It reminded me of the nine Muses of Ancient Greece: Clio, Euterpe, Thalia, Melpomene, Terpsichore, Erato, Polymnia, Ourania and Calliope. They were the goddesses that embodied science, literature, and the arts; if any of them have been looking over my shoulder, it must surely be Ourania, the inventor of astronomy and the Muse of astronomical writings.

But the Muses were – or are – pretty versatile. Two of them invented the theory of learning, three invented musical vibrations, four invented the four dialects of Ancient Greek, and five invented the five human senses. You will have noticed that this already adds up to more than nine; each Muse had several roles. Indeed, there is still more – seven Muses invented the seven chords of the lyre, the seven zones of the celestial sphere, the seven planets known to the Ancients, and the seven vowels of the Greek alphabet. As a tribute to them, and because I couldn’t fit everything into five themes, I have distributed my own thoughts about time, and in particular time travel, across nine essential topics – nine musings on time.

John Gribbin, April 2022

xx

Ourania

Sepia Times/Getty

* During its long history, Astounding appeared with several different variations on longer names, but always as Astounding something, before metamorphosing into Analog in 1960. For simplicity I will always refer to it by the short title.

INTRODUCTION

Time Travel is Not ‘Merely Science Fiction’

‘Time flies like an arrow – but fruit flies like a banana.’

Terry Wogan

There is a kind of science fiction in which all of the science is factual, but the action occurs in a fictional time or place. One of my favourite examples is the series of stories in the collection The Outward Urge, by John Wyndham,* which offers a blueprint for the exploration of near space. At the other extreme of the science fiction world there are stories which occupy the blurred frontier between science fiction and fantasy, a territory sometimes ventured into by Arthur C. Clarke, who once said: ‘Science fiction is something that could happen – but usually you wouldn’t want it to. Fantasy is something that couldn’t happen – though often you only wish that it could.’ It’s a good quip. I have my doubts about the accuracy of the last part, since The Lord of The Rings is 2archetypal fantasy but not something one would wish for, but it highlights where most people would think time travel sits on the spectrum between science fiction and fantasy.

Unlike space travel, a staple of fiction which is certainly possible, even if the propulsion systems invoked in stories are not yet (and may never be) practicable, time travel is, surely, something that couldn’t happen – though you wish that it could. Or is it? As I hope to make clear in this book, time travel is not forbidden by the laws of physics, and if it is not forbidden then it must be possible. Don’t just take my word for it. Oxford physicist David Deutsch has said: ‘I myself believe that there will one day be time travel because when we find that something isn’t forbidden by the over-arching laws of physics we usually eventually find a technological way of doing it.’

Time travel is not fantasy, and is not just science fiction either, although like space travel it is a common trope in science fiction. Also like space travel, it is serious science that has come under intense scrutiny from theorists (no surprise there) and has also been the subject, which may surprise you, of serious experimental tests. Anyone who dismisses time travel as ‘merely science fiction’ is wrong on scientific grounds, as well as being wrong to use the epithet, because the use of time travel in science fiction often highlights scientific truths in a way that scientific publications do not – I provide a good example in my Fifth Musing. But before I get into such deep waters, I need to lay out the landscape of space and time within which travel is possible.

* Originally published under the name Lucas Parkes; John Wyndham Parkes Lucas Beynon Harris, to give him his glorious full name, used several variations for his writings.

MUSING1

Time and Space are Components of a Flexible Spacetime

‘In some sense, gravity does not exist; what moves the planets and the stars is the distortion of space and time.’

Michio Kaku

‘Everybody knows’ that it was Albert Einstein who first described time as ‘the fourth dimension’ in his special theory of relativity, published in 1905. And ‘everybody’ is wrong – doubly so.

Ten years earlier, in 1895, H.G. Wells’ classic story The Time Machine was first published in book form. It was actually Wells who wrote, in The Time Machine, that ‘there is no difference between Time and any of the three dimensions of Space, except that our consciousness moves along it’. He goes on to describe objects we perceive in three dimensions, such as a cube, as actually being fixed entities extending through time, and therefore as having the four dimensions of length, breadth, 4height and duration. Even in 1905, though, Einstein did not describe time as the fourth dimension. The idea was actually introduced to the special theory by Hermann Minkowski, in a lecture he gave in Cologne in September 1908. Minkowski had been one of Einstein’s lecturers when he was a student in Zurich, and had famously described him then as a ‘lazy dog’ who ‘never bothered about mathematics at all’. But he was one of the first to appreciate that the lazy dog had achieved something remarkable with his special theory of relativity. In the introduction to his Cologne talk, Minkowski said:

The views of space and time which I wish to lay before you have sprung from the soil of experimental physics, and therein lies their strength. They are radical. Henceforth space by itself and time by itself are doomed to fade away into mere shadows, and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality.

That union soon became known as spacetime. But at first, Einstein hated the idea, which he saw as a mere mathematical trick; he rather ungraciously commented: ‘Since the mathematicians have attacked the relativity theory, I myself no longer understand it.’

‘The only reason for time is so that everything doesn’t happen at once.’

Albert Einstein5

H.G. Wells

Hulton Archive/Getty

6It is, actually, very easy to understand. Any location at street level in a city, for example, can be specified in terms of two numbers, or coordinates. I might arrange to meet you outside the building on the corner of First Street and Third Avenue. A third coordinate comes into play if we arrange to meet in the coffee shop on the second floor of that building. And time comes into the equation as the fourth dimension if we arrange to meet in that place at, say, three o’clock. Any location in space can be represented by three numbers, and any location in spacetime can be represented by four numbers. We all know the game where a series of dots on a page can be joined up to make a picture. The location of each of those dots is represented (in this case) by two numbers, its coordinates on the page. If the page is actually a rubber sheet and it is stretched, the picture becomes distorted, and the distorted picture can be described in terms of the way each of the dots has moved from its starting point. Equations that measure the relationships between the dots can be used to describe the distortion. In the same way, equations linking coordinates (dots) in spacetime can be used to describe distortions in spacetime.

Einstein came round to accepting this geometrisation of his theory when he realised that it was one of the keys to developing a more general theory of relativity, which would describe gravity as well as space and time. The special theory describes what happens to things moving at constant velocities through space. The general theory also does this, but in addition it 7describes what happens to things when they accelerate, and how gravity affects things. The equations (which, happily, I do not need to go into here) tell us that acceleration is exactly equivalent to gravity. Among other things, this produces the force on an astronaut in a rocket blasting off from Earth, usually measured in terms of ‘G’, the force of gravity at the surface of the Earth. A force of 4G literally means that the astronaut weighs four times as much as when on the ground. In orbit, falling freely around the Earth, which is a form of acceleration that never ends because the orbit is a closed loop, the astronaut is literally weightless because in this case the acceleration cancels out the Earth’s gravity.

In terms of the geometry of spacetime, gravity is a result of a dent in spacetime produced by the mass of the Earth (or any large object; technically, any object, no matter how small, makes a dent in spacetime, but the effects are too small to notice for everyday things like you, me, a coffee cup or the Taj Mahal). Nobody has yet come up with a better analogy for this than one involving a trampoline. If the trampoline is stretched tight then it forms a flat surface, equivalent to ‘flat spacetime’ where everything behaves in accordance with the special theory of relativity. Roll a marble across the surface and it travels in a straight line. Now place a heavy object, like a bowling ball, on the trampoline. It makes a dent. Try rolling a marble closely past the heavy object, and it will curve round the dent before proceeding on its way. This is like the effect of mass on spacetime, affecting the trajectories 8of objects so that it seems as if they are attracted by a force pulling them towards massive objects. But it is important to appreciate that the dent is in spacetime, not just in space. Time ticks by at a different rate in the distorted region of spacetime near a massive object, compared with the rate it ticks away at in flat spacetime.

We are now ready to look at the implications of all this for time travel. One possibility emerges from the special theory of relativity, which only applies in flat spacetime. It also emerges from the general theory, because the general theory contains everything the special theory contains, and more besides. For objects moving at constant velocities (which means at constant speeds in straight lines) in flat spacetime, the equations tell us about the relative behaviour of clocks (meaning any timekeeping devices) and measuring sticks (meaning any device to measure length) when things, such as spaceships, are moving relative to one another. It is all relative, because any ‘observer’ (such as an astronaut on board one of those spaceships) is entitled to say that they are stationary (‘at rest’) and everything else is moving relative to them. They are said to be in a ‘frame of reference’. Compared with that stationary observer, clocks on board a moving spaceship run slow, and the moving spaceship shrinks in the direction it is moving. Time literally runs more slowly in the moving spaceship, and the faster the ship goes (up to the speed limit set by the speed of light) the slower time passes. One reason why the speed of light is the ultimate speed limit is that at the speed of light time stands 9still – but this also has interesting implications for time travel which I discuss in my Fourth Musing. Because the astronaut in the moving spaceship is entitled to say they are at rest, and you are moving, to them it is your clocks that are running slow. Both viewpoints are valid, and there is no paradox because the two spaceships are never at rest alongside each other in the same frame of reference. But interesting things happen if they are brought together in that way.

If one spaceship goes off on a journey at a good fraction of the speed of light and then turns around and comes back to compare clocks, the astronauts will find that time has indeed passed more slowly in the spaceship that went away and came back, and any passenger on board that spaceship will have aged less than any companions who stayed at home. This is still not a paradox, because the situation is no longer symmetrical. We know which spaceship went away and came back, because it had to turn around. This involves acceleration, and a proper calculation of the time difference uses the general theory; but life is made easier for anyone wanting to do the calculation because it turns out that if we use the equations of the special theory applied to the outward and return legs of the journey separately, and make the unrealistic assumption that the turnaround happens instantly, it gives the same answer. At half the speed of light, time is slowed (‘dilated’) by 13 per cent; at 99 per cent of the speed of light, it is slowed by 86 per cent. At that speed, for every year that passes for the stay-at-home friend, just over a month passes for the traveller. 10A voyage lasting 50 years by the traveller’s clock would bring them back to find that while they had indeed got 50 years older, 350 years had passed at home, and their friend was long dead. The traveller has moved 350 years into the future while only living through 50 years.

‘You have to get old because of the geometry of spacetime.’

Brian Cox, Forces of Nature

This time dilation effect has been used as the basis for many science fiction stories, providing a means to take a one-way voyage into the future. My favourite is Poul Anderson’s Tau Zero, which pushes the idea to its logical limit.