Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Hard Case Crime

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Hard Case Crime

- Sprache: Englisch

QUENTIN TARANTINO on NOBODY'S ANGEL: "My favourite fiction novel this year was written by a taxi driver who used to hand it out to his passengers. It's a terrific story and character study of a cabbie in Chicago during a time when a serial killer is robbing and murdering cabbies. Kudos to Hard Case Crime for publishing Mr. Clark's book." TWO KILLERS STALK THE STREETS OF CHICAGO—CAN ONE TAXI DRIVER CORNER THEM BOTH? Eddie Miles is one of a dying breed: a Windy City hack who knows every street and back alley of his beloved city and takes its recent descent into violence personally. But what can one driver do about a killer targeting streetwalkers or another terrorizing cabbies? Precious little—until the night he witnesses one of them in action...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 273

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Raves for the Work of Jack Clark…

Some Other Hard Case Crime Books You Will Enjoy

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Nobody’s Angel

Raves for the Workof JACK CLARK…

“My favorite fiction novel this year was written by a taxi driver who used to hand it out to his passengers. It’s a terrific story and character study…Kudos to Hard Case Crime for publishing Mr. Clark’s book.”

—Quentin Tarantino

“Nobody’s Angel is a gem…which doesn’t contain a wasted word or a false note…it’s just about perfect.”

—Washington Post

“Heartbreaking…captivating…each page turn feels like real, authentic Chicago.”

—Chicago Sun-Times

“A pure delight for many reasons, not the least of which is the way Jack Clark celebrates and rings a few changes on the familiar private-eye script…There’s a memorable moment [on] virtually every page.”

—Chicago Tribune

“The cynical, melancholy cabbie point of view is perfect for this kind of neon-lit, noir-tinged, saxophone-scored prose poem, and Clark hits all the right notes.”

—Booklist

“Nobody’s Angel has the wry humor and engaging characters typical of the best of the hard-boiled genre, but Clark’s portrait of Chicago in the 1990s, with its vanishing factories and jobs, its lethal public housing projects, its teenage hookers climbing into vans on North Avenue, is what gives it legs.”

—Chicago Reader

“Nobody’s Angel is a powerhouse of a book, a genuine work of noir and one of the best books of the year…This is an incredible book that you will not soon forget.”

—Book Reporter

“Jack Clark’s descriptions are beautifully haunting and his plotting is exceptional.”

—Romantic Times

“[A] slim, sparse, and heartbreaking novel.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Engaging.”

—Library Journal

“There’s a world of intriguing and memorable detail expertly packed into two hundred pages and just the right amount of heartache. The book’s close features one of the best final lines of any book I’ve ever read. Please don’t pick it up and read that last page first, it’s so worth getting there naturally.”

—Barnes & Noble Ransom Notes

“A likeable protagonist and spirited, uncluttered prose: a promising debut by a Chicago cabbie who may drive a hack but doesn’t write like one.”

—Kirkus Reviews

As I slowed for the light, a young girl got off a bench. She was dressed in jeans and a powder blue jacket, with her hands pushed deep in her jacket pockets to guard against the cold.

The girl did a little step and shrugged slightly, and her jacket opened just a touch.

Her breasts were small and rounded. They seemed lighter than the surrounding skin, almost yellow, I thought, but maybe that was the glow of the street lights. Her nipples were hidden just beyond the edge of the jacket and I was almost ready to pay to see them. It was that nice a tease.

She closed the jacket and I looked up, and she smiled and blew me a kiss.

She was just another whore out on the street at five in the morning. But she was still subtle enough, or fresh enough, that she was also just a kid in jeans and sneakers.

A horn sounded and I looked up to find the light green. I pulled into the left-turn lane and looked back in the mirror. A van had pulled to the curb and the girl was leaning in the passenger window, casting a lean profile in my mirror.

I waited for a car to clear, then made the turn and headed north.

Maybe if I hadn’t been drinking it wouldn’t have taken so long to register. As it was, I was almost a mile away before it hit me. I made a U-turn and sped back, but the van and the girl were both gone…

SOME OTHER HARD CASE CRIME BOOKS YOU WILL ENJOY:

JOYLAND by Stephen King

THE COCKTAIL WAITRESS by James M. Cain

THE TWENTY-YEAR DEATH by Ariel S. Winter

BRAINQUAKE by Samuel Fuller

EASY DEATH by Daniel Boyd

THIEVES FALL OUT by Gore Vidal

SO NUDE, SO DEAD by Ed McBain

THE GIRL WITH THE DEEP BLUE EYES by Lawrence Block

QUARRY by Max Allan Collins

SOHO SINS by Richard Vine

THE KNIFE SLIPPED by Erle Stanley Gardner

SNATCH by Gregory Mcdonald

THE LAST STAND by Mickey Spillane

UNDERSTUDY FOR DEATH by Charles Willeford

A BLOODY BUSINESS by Dylan Struzan

THE TRIUMPH OF THE SPIDER MONKEY by Joyce Carol Oates

BLOOD SUGAR by Daniel Kraus

DOUBLE FEATURE by Donald E. Westlake

ARE SNAKES NECESSARY? by Brian De Palma and Susan Lehman

KILLER, COME BACK TO ME by Ray Bradbury

FIVE DECEMBERS by James Kestrel

THE NEXT TIME I DIE by Jason Starr

THE HOT BEAT by Robert Silverberg

LOWDOWN ROAD by Scott Von Doviak

SEED ON THE WIND by Rex Stout

Nobody’sANGEL

byJack Clark

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

A HARD CASE CRIME BOOK

(HCC-065-R)

First Hard Case Crime edition: February 2024

Published by

Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street

London SE1 0UP

in collaboration with Winterfall LLC

Copyright © 1996, 2010 by Jack Clark

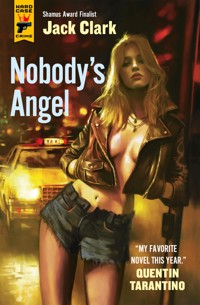

Cover painting copyright © 2024 by Claudia Caranfa

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher, except where permitted by law.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Print edition ISBN 978-1-80336-747-7

E-book ISBN 978-1-80336-748-4

Design direction by Max Phillips

www.signalfoundry.com

Typeset by Swordsmith Productions

The name “Hard Case Crime” and the Hard Case Crime logo are trademarks of Winterfall LLC. Hard Case Crime books are selected and edited by Charles Ardai.

Visit us on the web at www.HardCaseCrime.com

To the memory of Mayor Harold Washington,the best friend Chicago cabdrivers ever had.

NOBODY’S ANGEL

SKY BLUE TAXI

INITIAL CHARGE$1.20FIRST 1/5th MILE.20EACH ADDITIONAL 1/6th MILE.20WAITING TIME (EACH MINUTE).20ADDITIONAL PASSENGERS (EACH).50TRUNKS.50HAND BAGGAGE CARRIED FREE(RATES IN EFFECT FROM MARCH 1990 TO JANUARY 1993)

CITY OF CHICAGO

INCORPORATED 4th MARCH 1837

PUBLIC PASSENGER CHAUFFEUR’SLICENSE

EDWIN WMILES

Department of Consumer Services

It was a beautiful winter night but everybody was home hiding from a snowstorm that would never arrive. Everybody but the cabdrivers. We were sitting around the Lincoln Avenue round-table—a group of rectangular tables and the surrounding booths in the back of the Golden Batter Pancake House—everybody bitching and moaning, which is the routine even on good nights.

Escrow Jake was into a familiar rant about TV weathermen. “When they say, ‘Whatever you do, don’t go outside,’ what they really mean is: ‘Stay home, watch TV and see how fast my ratings and my paycheck go up.’”

Jake had been a lawyer until he got disbarred for squandering escrow accounts at various racetracks. He was still a degenerate gambler but now he drove a cab to feed his habit. Only his very best friends called him Escrow to his face.

In the booth behind Jake, Tony Golden and Roy Davidson were schooling a rookie in the art of survival. Golden had grown up on the black South Side. Davidson was white, from the hills of Kentucky. But they were the best of friends. And they both loved the rookie. Everybody did.

There weren’t many Americans entering the trade, and the kid was white to boot, which made him about as rare as a twenty dollar tip.

“Don’t go south,” Davidson warned him.

“Keep your doors locked,” Golden advised. “Especially that left rear one. They love to slip in that left rear door.”

“Don’t go west,” Davidson added.

“Then they can sit right behind you and when the time comes, bam, they’re over the seat.”

“Don’t go into the projects.”

“I don’t even know where all the projects are.” The rookie sounded shaky.

“You know what Cabrini looks like?” Davidson asked.

The rookie said he did. Everybody knew what the Cabrini-Green housing project looked like.

“That’s all you got to know. Don’t go south. Don’t go west. Don’t go anywhere looks like Cabrini.”

“But I won’t know till I get there,” the rookie said.

Good point, kid, I thought. Good point. And I remembered my own days as a rookie and my first trip to the pancake house.

I’d cut off another taxi. The cab came around me at the next red light, pulled into the intersection, then backed right to my bumper.

The guy who’d gotten out wasn’t that big, but he walked back slowly, with plenty of confidence, ignoring the horns that started to blare as the light turned green.

“Jesus, you’re white,” Polack Lenny said as cars squealed around us. “Why you driving like a fucking dot-head?” I was to discover that this was Lenny’s harshest insult.

“Sorry. I didn’t see you,” I lied. “Just trying to get back to O’Hare.”

“Oh, boy. How long you been driving?”

“Couple months,” I admitted.

“Never go back,” he said. “Haven’t you learned that yet? You never go back.”

“It’s really moving out there,” I said.

He shook his head sadly. “Stop by the Golden Batter on Lincoln some night. You can buy me a cup of coffee.”

He jogged back to his cab, jumped in, and made the light as it was changing. I waited for the next one, then wasted twenty minutes speeding to O’Hare to find the staging area full of empty cabs.

Later that night I bought Lenny a cup of coffee. It was the first of a few thousand conversations we would have at the roundtable. It was easy to learn when Lenny was talking. “People don’t want to hear how bad business is,” he told me that first night. “They got problems of their own. So if they ask, just lie and say you’re having a great time. You might even start to believe it.”

Tonight, drivers were remembering and concocting long trips. St. Louis, Louisville, Miami, Los Angeles, Anchorage. Lenny, sitting at the head of table number one, cut everybody off. “You want to talk about long trips, I’ll tell you about a long trip.”

Ace, sitting across from me, winked.

“Here we go,” I whispered.

But the whole place shut up. There must have been thirty drivers, and many had already heard Lenny’s favorite story. I’d heard it several times myself. But this is the night I always remember.

“This is years ago,” Lenny said. “I’m on LaSalle Street in the Loop when this guy in a bowler hat flags me with his cane. ‘Buckingham Palace, please.’ Like it’s right ’round the corner. ‘Listen, pal,’ I tell him. ‘I can get you to the fountain for a couple of bucks but the palace is about four thousand miles.’ ‘The palace, please.’ Well, I’m getting a little annoyed. ‘You think I got wings?’”

Lenny does the English guy with puckered lips: “‘I believe there’s a ship leaving the Port of New York in seventeen hours, twelve minutes.’ So, what the hell, I get on the horn and dispatch comes back with an even twelve grand. ‘Get the money up front and save the receipts.’”

“Twelve thousand dollars?” the rookie whispered as Lenny began to reel in the line.

“The English guy opens his briefcase and counts out twelve thousand in hundred dollar bills. Then he says, ‘Drive on, Leonard.’”

Leonard. Half the room died. It was a brand new touch.

“Six days later we pull up in front of Buckingham Palace and he says, ‘Ta-ta, Leonard. Thank you very much.’ And he hands me a ten pound tip.”

“Lenny, you are so full of shit,” someone said, and someone else said, “You’re just figuring that out?”

Didn’t faze Lenny. “Hear me out. You ain’t heard the kicker. So I start back for the docks. Haven’t gone two blocks when all a sudden I hear, ‘Sky Blue! Sky Blue!’ I stop and here’s this guy lugging a couple of guitars and a suitcase. ‘You’re a Sky Blue Cab from Chicago, right?’ ‘What’s it look like, pal?’ ‘Can you take me back there? I was just on the way to the airport but I hate to fly.’ ‘Well, sure. But, look, it’s twelve grand and I gotta have it up front. Cash.’ ‘That’s no problem,’ he says. ‘Can you get me there by Saturday night? I got to be at 43rd and King Drive by six o’clock.’”

Lenny held up his hand like a cop stopping traffic. “‘Whoa. Look. Sorry, pal, nothing personal but…’” He gave it a long beat. “…‘I don’t go south.’”

The place exploded in laughter. Even guys who’d heard it before were howling. I looked over and the rookie was laughing along with the crowd but you could tell he didn’t really get it. He was probably thinking about driving a truck for a living or something sensible like that.

Clair, my favorite waitress, came by with a coffee pot and a rag to clean up the spills. She caught my eye and flashed a smile.

Ace winked. “She likes you, Eddie.”

“She’s married.”

“And?”

“And she’s not that kind of girl,” I said. But in my dreams she was.

“The things you don’t know about women,” Ace said.

All taxicabs shall have affixed to the exterior of the cowl or hood of the taxicab the metal plate issued by the Department of Consumer Services. No chauffeur shall operate any Public Passenger Vehicle without a medallion properly affixed.

City of Chicago, Department of Consumer Services, Public Vehicle Operations Division

It was another quiet night—the tail end of that same winter—the last time I saw Lenny.

I was northbound on Lake Shore Drive, fifteen over the special winter speed limit, which was supposed to keep the road salt spray from killing the saplings shivering in the median.

The lake was a vast darkness on the right. To the left lay the park and beyond that a string of high-rent highrises climbed straight into the clouds.

A shiny Mercedes shot past in the left lane. A rusty Buick followed along. I flipped the wipers on to clear the mist that had risen off the road.

A horn sounded. I looked over as a brand new cab slipped up the Belmont Avenue ramp. I slowed down a bit and the cab pulled alongside. The inside light went on and Polack Lenny pointed a long finger at his own forehead. I couldn’t read his lips but I knew that he was once again calling me a dot-head. “Hey, Lenny.” I turned my own light on and gave him the finger in return.

For most of the years I’d known him, we’d both driven company cabs. I hadn’t known his real name until he’d won a taxi medallion in a lottery and put his own cab on the street. I’d been one of the losers in that same lottery, and I was still driving for Sky Blue Cab.

LEONARD SMIGELKOWSKI TAXI, Lenny’s rear door proudly proclaimed. His last name took up the entire width of the door, which had some obvious advantages. He might never get another complaint. Everybody’d get too bogged down with the spelling.

Lenny took both hands off the steering wheel and waved them around for me to see. I could almost hear his gravelly voice, “Look, Ma, no hands.” He was obviously having a good time and he was probably rubbing it in a little. I was driving a three-year-old beater with 237,000 miles on it. If I took my hands off the wheel I’d end up bathing with the zebra mussels, and Lenny knew it.

He put one hand back on the wheel and turned the other thumb down. I pointed a thumb in the same direction. It had been that kind of night. I held an imaginary cup of coffee to my lips and took a sip. Lenny shook his head, then laid his head on a pillow he made with one hand. He waved one last time, then his inside light went out and his cab dropped back.

“What was all that?” my passenger asked as I sped back to 55.

“Just your typical bitching and moaning,” I explained.

“It must be kind of scary.”

“What’s that?”

“All those drivers.”

“What drivers?”

“The ones getting shot. It must be kind of weird.”

I’ll bet, I thought, and I glanced in the mirror. He was slouched in the corner of the seat, looking towards the lake. His face had lost some battle years ago and was now dotted with scores of tiny craters. His hair was long and streaked with grey. He was too old to be dressed in trendy black, to be nightclubbing on a quiet Tuesday night. He was the kind of guy who would always go home alone.

“What’s your line?” I asked.

“I don’t follow you.”

“What sort of work you do?”

“Graphic design.”

“Now that sounds scary.”

He laughed. “Yeah, but nobody shoots us.”

“Probably all shoot yourselves out of boredom,” I said.

“Hey, what’s the problem, man?” The guy sat up straight and gave me a hard look.

“Just making conversation,” I said, the most easygoing guy in the world.

I took the Drive until it ended, then followed Hollywood into Ridge. Past Clark Street, Ridge narrows and winds along, following some old trail. A few blocks later, parked cabs lined both curbs. Lenny wasn’t the only one who’d given up early.

A skinny guy with a beaded seat cushion under his arm was leaning against one of the taxis. He looked my way and drew a circle in the air. A nothing night, I deciphered the code. I waved and tapped the horn as I passed.

The meter was at $12.80 when I stopped just shy of the Evanston line. The guy handed me a ten and three singles and got out without a word.

“Thanks, pal. I’ll buy the kid a shoelace.”

Everybody wants a driver who speaks English until you actually say something.

A few years earlier I would have cruised Rogers Park looking for a load. It had been one of Chicago’s great cab neighborhoods. There’d always been somebody heading downtown.

There were still plenty of decent folks around, black and white, but just to be on the safe side, I turned my toplight off, flipped my NOT FOR HIRE sign down and double-checked the door locks.

The sign didn’t necessarily mean what it said, and the decent folks usually knew to wave anyway. But with the sign down, I could pass the riff-raff by without worrying about complaints.

I drifted east, working my way to Sheridan Road, and then headed south back towards the city.

On Broadway, I spotted Tony Golden locking up his Checker. I tapped the horn. He looked my way and pointed both thumbs straight down.

A few minutes later, in the heart of Uptown, a couple staggered out from beneath the marquee of a boarded-up theater. I slowed to look them over, then stopped.

The woman opened the door behind me. Her blouse was undone. Someone had been in a big hurry and popped all the buttons. She’d tucked the tail into her skirt, but when she leaned into the cab, I had a clear view of some very inviting cleavage.

“Hello,” I said.

“You go Gary?” she asked. She didn’t sound like she’d been in country too long. She was small and dark, with high cheekbones and probably more than a trace of Indian blood. One tiny brown hand rested on the back of my seat.

“Indiana?” I asked.

She nodded and her breath reached me and suddenly she wasn’t pretty at all.

“Sure,” I said. Gary was thirty miles. I pushed a button to lower the driver’s window and took a deep breath of city air.

“How much dollars?” she wanted to know.

“Say forty bucks.” I gave her the slow-night discount. “But I gotta have the money up front.” And I would have to keep the window cracked all the way.

She turned to her partner and spoke in Spanish. He was a sawed-off guy wearing cowboy boots that still left him well below average height. He pushed her out of the way and leaned in the door. His breath wasn’t any better. He could barely stand. “Fucking thief,” he said, and slammed the door.

I coasted a few feet then sat waiting for the light to change. In the mirror I watched the pair stumble up the block to a big, beat-up Oldsmobile, a gas guzzler if there ever was one. They were a couple of drunks left over from some after-work saloon and now little man was going to drive the lady all-the-way-the-hell to Indiana. When they got there, their breath would mix nicely with Gary’s coke-furnace air.

The light changed and I started to roll.

“Cab!”

Two guys in business suits bolted out of a nearby nightclub. I stopped halfway into the intersection. A car trapped behind me blasted its horn.

The first one in the door was a kid of about thirty. He was lean and trim with short, sandy hair. He wore a pale pinstripe suit. Some sort of junior executive, I decided. The second guy looked more like the genuine article. He was ten or fifteen years older and somewhat heavier, with lines in his face and grey in his hair. His suit was a deep, dark blue with tight, gold stripes.

“Jesus Christ, get us the fuck out of this neighborhood,” Junior said.

The trapped car finally got around me. “Asshole!” somebody shouted as it squealed past.

“Hey, this is a good neighborhood,” I said. I followed Broadway as it curved east and went under the elevated tracks. Off to the right a group of winos were passing a bottle around. They hadn’t even bothered with the time-honored paper bag.

“Looks like New York to me,” Senior decided.

“You want to see some bad neighborhoods,” I offered. “I’ll show you some bad neighborhoods.”

“I’ve seen enough,” Senior said. “Take us back to the Hilton.”

I cut over Wilson Avenue and headed towards Lake Shore Drive, a few blocks away.

“Sorry about tonight,” Senior said. “Tomorrow we’ll try Rush Street. Can’t go wrong there.”

“I’ll never trust you again.”

“Used to be everything north was nice. ’cept for Cabrini, of course.”

“What’s Cabrini?” Junior wanted to know.

“Worst housing projects in Chicago,” Senior said. “You know the first trip I ever made here I got some advice that served me well. Guy told me two things to remember about Chicago. Don’t go too far south and keep away from Cabrini-Green.”

“Here’s how it really goes,” I chimed in. “Don’t go too far south. Don’t go anywhere west. Be careful when you go north.”

“What about east?” Junior wanted to know.

We were southbound on the Drive by then. I gestured towards the lake where a light fog was rolling in. “Can you swim?”

“It’s still a great city,” Senior said. “Too bad we can’t see anything. Best skyline in the world.”

There was a wall of fog-shrouded residential highrises on our right, most of the windows dark for the night. The towers of downtown were concealed behind thick clouds.

“Where you guys from?” I asked.

“Indy.”

“Naptown,” I said.

“A nice place to raise a family,” the senior man informed me.

“We’ve got some of those around here someplace,” I remembered.

An empty Yellow shot past, its toplight blazing away.

“I hear you guys been having some problems,” Senior said as I flipped the wipers on in the taxi’s wake.

“What’s that?”

“Somebody killing cabdrivers.”

“Christ.” That was all anybody wanted to talk about.

“Seven guys killed, that’s something.”

“Three,” I corrected him.

“Seven, three, whatever,” Senior said. “It’s gotta make you nervous.”

“I’ve been driving for twenty years,” I lied, “I was born nervous.”

They both laughed.

“You know what a taxi rolling through the ghetto is?” I asked.

“What’s that?”

“An ATM on wheels.”

“You don’t go there, do you?” Junior said.

“Where?”

“You know, those neighborhoods.”

“I don’t have any choice.”

“Just pass ’em by,” Senior advised.

“It isn’t that easy,” I explained. “Say you’re driving by some fancy highrise and the doorman steps out blowing his whistle. You pull in and out walks the maid going home. What you gonna do?”

“Just step on the gas,” Junior had the answer.

“Then they write your number down and call the Vehicle man.”

“Yeah, but you’re alive,” Senior said.

“But eventually I’m out of a job. And, what’s the big deal? It’s just some old lady trying to get home.”

“And you’ll just be another dead cabdriver,” Senior said.

“There’s worse things.”

“Name some.”

“What kind of work you guys do?”

“Sales,” Senior answered.

“Hardware.” Junior fell into the trap.

“There you go.” I said.

It took a minute to sink in. “They must send you people to school, teach you to be so disagreeable,” Senior said.

“Just something I learned from all my wonderful passengers.” And that was the end of that conversation.

I got off at Wacker Drive and took the lower level around the basements of the Loop. This was the city’s famous two-level street. The downstairs was dark and dingy, full of loading docks, dumpsters, rats and bums. The detour added about a mile to the trip. The Hardy Boys knew what I was doing but neither had the balls to call me on it.

“Fourteen-fifty,” I said when we pulled up in front of the Hilton.

Hotel Steve’s Yellow was in the cab stand. Steve appeared to be sound asleep. But he’d wake at the first sign of a suitcase. “The ritzier the hotel,” he’d told me once, “the worse the tip.” And he was the man who would know. He spent a good part of his life asleep in hotel lines.

Senior threw a twenty over the front seat. “Keep the change, asshole,” he said. I guess he was trying to prove some point but it was lost on me. I wouldn’t have tipped myself a dime.

I cruised downtown for a while but nothing was going on. Traffic signals turned from red to green to amber. Three out of four cars were empty cabs.

The cleaning ladies were getting off work, hurrying towards State Street to get the bus out to the Southwest Side. The last time one took a taxi was 1947.

I drove up Dearborn, beating a Checker for the federal courthouse side of the street, then cruised along hoping for a lawyer or maybe a late-night jury but there was nobody around.

At Monroe, two guards led a bum up from the First National Bank plaza and pointed him south.

Up the street, the Picasso sculpture rusted away in the plaza of the Daley Center. Nobody came up from the subway. A Flash Cab cut in front of me and turned west. I continued north, over the river.

Empty cabs were sitting in front of most of the popular nightclubs. More sleeping drivers, a sure sign they’d been waiting too long.

In an industrial area north of Chicago Avenue, I pulled into an alley to take a leak. A van was sitting in darkness at the other end of the alley. I started to back out to find a more secluded spot but then the lights of the van came on and it pulled away. I shifted back into drive, coasted to the middle of the alley, stopped, turned my headlights off and opened the door.

There was a truck yard on my side of the alley, enclosed by a cyclone fence which was strewn with windblown litter and overgrown weeds. On the other side of the alley an old factory had been converted to lofts.

I was almost finished when I heard the sound. It was muted at first, a cat’s cry floating on the wind. Then it came again, louder and much closer, a strange, high-pitched whimper. The hairs on the back of my neck stood on edge. I finished quickly, jumped in the cab and stepped on the gas.

Toward the end of the alley where the van had been, a pile of garbage lay across my path. As I approached, the pile shifted. Something flashed briefly, caught in the headlight beam. A pair of eyes.

I heard my father’s voice, my very first driving lesson: “Never run over a pile of leaves.” I laid on the brakes, jammed the cab into reverse, and shot back out the way I’d come in.

I sat there facing the alley. I flashed my brights a few times but now there was nothing to see; just a dark pile alongside an overflowing dumpster. Could I have imagined the eyes?

I turned east and started away. Whatever or whoever it was, it wasn’t my concern.

That got me out to Wells Street, where a string of empty cabs was heading north for home. I didn’t see anybody I knew. That’s the way the business was heading, more Indian, Pakistani, and East African drivers and fewer Americans every day.

I thought about the eyes, about the movement in the pile of trash. It was probably nothing, I decided. And I remembered Polack Lenny’s lesson: Never go back.

Oh, the hell with that. I released the brake, circled the block and pulled up to the mouth of the alley, about ten feet shy of the dumpster. I stopped with my headlights trained on the pile, grabbed my canister of mace, got out and approached slowly.

There was a rolled-up furniture pad lying next to the dumpster. The pad was torn and soiled and, if there was anything inside, it wasn’t very big. I tiptoed closer and there weren’t any eyes. There was broken glass scattered around—maybe some of that had reflected my headlight beam. “Hello,” I said, just to be sure, and I tapped the pad with my foot.

The pad moved. I jumped back as a corner slid downwards and the pair of eyes reappeared. They didn’t look up. They were just there. A pair of shadowy eyes set in a small dark face.

I moved forward slowly, holding the mace out front, my finger ready on the trigger. Christ, it looked like a kid. A little black kid hiding in a furniture pad in the middle of an alley. Two narrow wrists were crossed and a pair of tiny black hands gripped the edge of the pad.

It was a girl, I realized. She was lying on her side, curled up inside the pad. If size was all I had to go on, I would have guessed she was somewhere around nine or ten. But there was something much older in those eyes. “You okay?” I said.

“I’m cold, mister,” she whispered. I could barely make out the words. “Real cold.”

“You’re gonna be okay,” I said and the girl uncrossed her wrists and showed me how wrong I was.

The pad opened. Someone had cut her to ribbons. Thick brown ribbons and narrow red ones that flowed down her chest and soaked into the pad. I turned my head away. “I’ll get help,” I whispered and I hurried back to the cab.

I grabbed the microphone and hit the switch for the two-way radio. “Ten-thirteen,” I shouted. “Ten-thirteen!”

A dispatcher came on. I gave him my location and cab number. “There’s a kid here, in the alley,” I said, leaning into the cab so she wouldn’t hear. “I think she’s been stabbed. She’s bleeding real bad.”

“Stand by, sir, while I call the police.”

“Call an ambulance,” I said.

“Check,” the dispatcher said.

I looked up. The girl had rolled and now lay on her back, one knee in the air, the pad wide open. She wasn’t wearing a stitch of clothes. Her chest was a bloody mess. Her head was turned my way but even in the headlight beam her eyes seemed hidden behind a cloud.

A triangular patch of curly black hair caught my attention. She was no nine year old. But she was still a kid. Fourteen or fifteen. That was my new guess. A kid that someone had dumped like a piece of garbage.

I switched my headlights off. “They’re gonna get help,” I called. For a second her eyes seemed to focus. “You’re gonna be okay,” I said.

It seemed like long minutes before the dispatcher finally returned. “The police and ambulance are on the way,” he announced.

“Thanks.”

“The police request that you stay there until they arrive.”

“I’m not going anywhere,” I said.

“Thank you, units, for standing by,” the dispatcher said, addressing the rest of the Sky Blue fleet. “At 1:07 A.M. the emergency is clear. Let’s go back to work.”

I flicked the radio off. “The ambulance is on the way,” I said. In the distance I heard the first siren.

“I’m cold,” the girl said.

I walked over and lifted one end of the pad and draped it back over her. It was heavy with blood and with pebbles and dirt that clung to it. A hand grabbed my leg. Even through my trousers it felt as cold as ice. “Don’t go,” the girl said softly, and then she said something too faint to hear.