23,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: novum publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

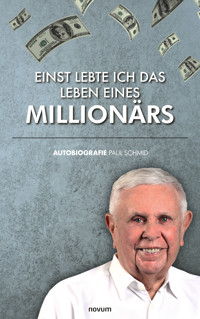

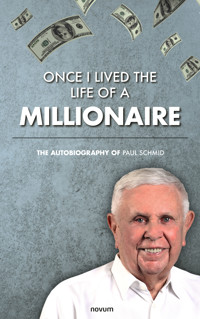

We hear again and again in politics how "entrepreneurs have to bear all the risk." Paul Schmid shows us exactly what this means and where it can lead in his autobiography, "Once I lived the life of a millionaire." Woven into his family history, the engineer describes how he worked his way up to become a key player in the telecommunications industry, starting with a product he developed on his own and at his own risk. However, his many successes also led to more responsibility and, with it, greater financial risk. The book shows how quickly the wind can turn due to changes in the industry, and above all, the global economy, and how an entrepreneur can slip into serious difficulty through no fault of their own.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 281

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Imprint

All rights of distribution, also through movies, radio and television, photomechanical reproduction, sound carrier, electronic medium and reprinting in excerpts are reserved.

© 2025 novum publishing gmbh

Rathausgasse 73, A-7311 Neckenmarkt

ISBN print edition: 978-3-99130-729-7

ISBN e-book: 978-3-99130-730-3

Cover photos: Roystudio, Andrew7726 | Dreamstime.com; Andrea Giovetto, FOTOGIOVETTO

Cover design, layout & typesetting: novum publishing

Internal illustrations: Paul Schmid, Peter Schmid, Sandra Werneyer-Misteli

Author’s photo: Andrea Giovetto, FOTOGIOVETTO

www.novumpublishing.com

Preface

Once I lived the life of a millionaire

Spent all my money, I just did not care

Jimmie Cox lyricist and composer (1882–1925)

Autobiography Paul Schmid

My mother, Berta Schmid-Bürgi, grew up with her two older brothers Karl and Paul in Gachnang, Switzerland. “Berteli” Bürgi was a cheerful girl, well known to everyone in the small farming village.

Her parents’ house, located at what was once the exit from the village, still stands to this day. The former country road led right past the house and immediately afterwards up the mountain via Oberwil to Frauenfeld. If you take the path by foot, you’ll get to Frauenfeld in just under an hour. A classic farmer’s garden adorned the old half-timber construction, and behind it, the view opened out onto a magnificent garden of over seventy high-trunk fruit trees. In the barn were fifteen cows and a few oxen. Her father, Karl Bürgi, traded the oxen in addition to his business in fruit and dairy products. He bought the young animals, taught them to work, and sold them on for a small profit.

The water of the well rippled day and night beneath the window of Berteli’s small room, and the same pairs of swallows would nestle in the room year after year.

Life on the farm was far from idyllic, though. Berteli’s mother passed away when she was just seven years old. One Anna-Maria Lampert, an attractive twenty-three-year-old, came all the way from Grisons to work on the farm as a maid, bringing two illegitimate children with her. The widower soon married the maid, twenty-eight years younger than him, and the number of children on the farm grew from five to seven.

Berteli loved going to school; she found learning easy. Ninety children were taught in one schoolroom by a single teacher. The older, stronger students had to help teach their younger classmates to read, count, and write. Berteli’s academic achievements were easily sufficient to go onto secondary school, but her father refused to let her. He seemed to value her help on the farm more. Berteli never forgave him for this harsh decision.

She was only seventeen years old when her father died of pneumonia. Her older brother Paul took up the mantle of head of the family after being appointed as guardian to Berteli, even though she was just four years his junior.

The enterprising stepmother and widow Anna-Maria, only thirty-four years old, did not find it difficult to find a new pair of hands to man the farm. The new marriage soon produced two more children, breathing more life into the beautiful half-timber building.

Berti told herself: “Why ask lots of questions about money and property if I’m happy?” (Johannes Martin Müller, 1750–1814). She left all the household effects bequeathed to her by her brother Paul to the farm’s numerous residents and set up her own family at the age of twenty-one, far away from her parents’ old home. The scene: The grand St. Ursen Cathedral in Solothurn. The only souls present were the bridal couple, their witnesses, and the pastor.

The lucky man she chose was named Konrad Schmid. He spent his early youth with very old parents and in poverty. He was reluctant to look back on his youth as an indentured child, but he was delighted to talk about the first job he chose for himself, electrifying railway lines as a trained overhead line technician. He’d proudly ride his BSA to work in 1925, stopping off on the way home at the stocking collection points that his young wife had set up to earn a little money toward the household’s budget by repairing stockings.

In 1932, my father moved to Zurich’s state electricity plant—the EKZ—in the district of Winterthur as an overhead line mechanic. In the Great Depression and subsequent war years, young men absent due to military service found their professional development stunted, especially those who were at the start of their working lives and the bottom of the career ladder. In the economic upturn after the war ended, the EKZ entrusted more demanding tasks to my father, which was reflected in the fact that his salary was no longer a worker’s but an employee’s, and it rose steadily albeit slowly. The couple used these funds to fulfill their greatest dream, which was to give their two sons a better start in life with a good education.

***

My brother Konrad was born on March 2, 1931, a good two years before me. He was my parents’ favorite, especially whenever we brought home our school reports. His last elementary-school report, top grades all around, included just one five-and-a-half out of six.

Konrad combined his many talents and outstanding intelligence with great ambition, which ensured they didn’t go unexploited. He learned to play the piano from a teacher of classical music, and later a well-known entertainment and jazz pianist in Zurich taught him “underground music”. After two years of grammar school, he switched to a vocational high school, where he and some of his classmates founded the Eleonora Jazz Society. The name was not inspired by a pretty singer, but by the street where a popular community jazz cellar was located. He bought one of the first Revox tape recorders to record his music, a Dynavox with two heads and two motors. After studying the device, Konrad built an even better one with three heads and three motors. He also added an amplifier and other electronic devices for personal use. Konrad devoured technical literature as avidly as other boys gobbled up detective stories. This curiosity for all kinds of advances in technology remained unabated for the rest of his life.

With a diploma as an electrical engineer from the Federal Institute of Technology in his pocket, Konrad took up his first job at the RCA laboratory on Hardturmstrasse in Zurich in January 1957. To introduce him to his role, Konrad spent several months in the RCA’s famous laboratories in the U.S. This was when his admiration for Americans’ technical prowess in the field of electronics—as well as their gift of forming lasting friendships—began. In the evenings, he enjoyed the music of legendary pianists like Teddy Wilson in the jazz bars of New York.

Konrad then worked around Europe helping radio and television factories use RCA patents: he spent the incredible summer of 1960 in a factory by the sea just north of Stockholm. Assuming Sweden was always this nice, he left his parents’ apartment on his thirtieth birthday—a deadline that had been set for him a long time before—and drove his MG TF up to Gothenburg, where an assistant position was waiting for him at Chalmers University of Technology. His research was aimed at improving electronic medical devices.

He rented his first apartment in Gothenburg and used what little money he had left over to buy first a bed and second a grand piano. After a few years, Konrad was allowed to give his own lectures. To his students’ amazement, he would transfer his manuscripts to the blackboard in English while lecturing in Swedish. At the same time, he worked toward his doctorate in technical sciences at Chalmers University of Technology.

A concert by Hazy Osterwald thrilled Konrad so much that he invited the whole band—along with some pretty blonde Swedes—back to his place. He liked one of the blondes, Bodil Ericsson, so much in her traditional dress that on May 5, 1967, an unforgettable wedding party took place at her parents’ home on a rocky outcrop above the fjord.

Konrad and Bodil went on to spend more than two decades of their summer vacations in a seaside vacation home in Lysekil that belonged to Bodil’s parents. Konrad enjoyed sailing in the archipelago with Bodil’s many cousins, swimming in the cold sea, and hauling the net out of the sea at dawn to release fish, crabs, and even lobsters from their agony for that night’s dinner. If the catch was worthy of an exuberant celebration, he had no trouble keeping up. He loved to dance all night long, even though he was well aware that he would have to stand knee-deep in cold water for a while before going to bed to relieve the pain in his varicose veins.

***

On May 6, 1933, I, Paul Schmid, first saw the light of day—blessed by fate—born to parents who never put their marital bliss at risk, who loved their children above all else, demonstrated endless patience, and were always there for us when we needed them.

Even as a young boy, I liked to chase after my thoughts, preferred to be alone or at most one on one to organized group activities like scouting expeditions, avoided fights, absolutely abhorred gym class, had no idea what to do with a ball, and was probably considered something of a nerd by my peers. Instead of playing out in the street with them, I crept around the neighboring sheds and garage. The truck, a Saurer diesel, could turn up at any time, though in those years it ran on wood gas. My timely opening of the gate and other helping hands occasionally prompted the driver to invite me on short—and sometimes long—trips.

My parents realized early on that, after a first push with “Heidi” by Johanna Spyri, they need not give me a second children’s book, but a subscription to the Automobil Revue. The weekly magazine explained all the latest technology in great detail, putting me on a completely different level from my classmates—who only collected glossy brochures—when it came to talking about motor vehicles… I couldn’t even talk to them about cars.

Thanks to my father’s promotion, we now lived in an official apartment in a building belonging to the EKZ’s Winterthur District Directorate. Half a dozen cars by different manufacturers lined the forecourt. After school, I’d toss my backpack under the ramp and start tending to the cars pulling in. They not only required all manner of cleaning, but also, since they were pre-war models, frequently checking their coolant, oil, and air. Once my work was done, I’d carefully drive the cars into their bays. My father’s staff laughed when they found me with a pillow under my arm: it gave me the precision I needed to operate the steering wheel. I could pull off all the maneuvers required without ever causing even the slightest damage, though. The freedom that I enjoyed from the age of thirteen through fifteen also undoubtedly owed in part to the high esteem my father enjoyed among his co-workers.

Now, after this single highlight of my day, I would have to buckle down to my schoolwork and sit at the piano. What I tried to play did not enthuse my piano teacher, and I wasn’t so keen on what she had me practice either. I paid no attention to her notes in my music booklets; I could play all the pieces by heart thanks to my musical memory. After two years, my efforts came to an end. My brother Konrad displayed much more motivation at the piano too. It was through him that I discovered the marvelous music of American pianists—most of them Black—like Fats Waller, James P. Johnson, and Teddy Wilson. I’d practice the left hand—which forms the basis of the stride style—for hours and hours.

My receptivity knew hardly any limits for everything I was interested in; French and Latin were not among them. After a little over a year of grammar school, this led to a succinct conclusion in my report: “Sent back to first grade.” That wasn’t especially encouraging. So, after the summer vacation, I headed off to the public middle school. With no formalities, which still amazes me to this day, within a few minutes I was already in second grade, right in front of my former class tutor and Latin teacher’s pretty daughter. That gave me the certainty that, again without a single formality, I’d be struck from the grammar school attendance list in the afternoon.

In mid-July 1948 my father’s employer, the EKZ, asked him to take on an even more demanding task at the company’s headquarters as soon as possible. The move from an official residence in Winterthur to one in Zurich took less than three weeks. After the summer vacation, I again found myself in a new class, this time in the third grade of middle school in the Zurich neighborhood of Wiedikon, again without so much as a chance to say goodbye to my old classmates. I wasn’t particularly interested in my remaining time at middle school. I focused all my energy on getting my father to find me an apprenticeship as a mechanic. This hurt him a great deal because it had taken him years to grow out of his working-class roots. Finally, though, he made my wish come true.

In the spring of 1949, I started my apprenticeship in the Triemligarage under the tutelage of Emil Horber. It was six-day, fifty-four-hour week, and I earned five francs a week in the first year of apprenticeship, then ten francs in the second. The garage did not have its own salespeople. We repaired all brands of cars except VW, Mercedes, and Citroen, plus trucks and even tractors. My theoretical knowledge was beyond that of many trained mechanics, so I was allowed to work with relative freedom. I was particularly enthused to be able to carry out a small refurbishment of a CT1D engine in a Saurer diesel truck belonging to Hürlimann Brewery—I knew that the CT1D, which went into production in 1935, had proven to be groundbreaking in engine construction, thanks to promising innovations like direct injection, double-swirl chambers integrated into the pistons, four valves per cylinder, and wet bushings. After covering up the engine, I was able to admire the strong bolts with the tapered shaft modeled on the power line flow: top-notch mechanics!

In the very first year of my apprenticeship, I asked my father for a small loan to buy a Ford Anglia that was no longer roadworthy: the side-mounted camshaft had seized up. Back then, long-stroke engines weren’t up to great mileage, so once an engine had been removed, it made sense to completely refurbish it. My parents’ apartment had a vegetable cellar that was perfectly suited as a workshop. It never smelled of engine grease, just Grafensteiner, Berner Rose, and bell apples and pastor pears from my step-grandmother’s farm.

I used a shoot from all the potatoes—too many potatoes, if you asked me—for the only job that requires a certain level precision when putting together an engine: adjusting the camshaft. One wrong move and the almost one-liter, four-cylinder engine would not have reached its rated output, 24 hp at 4000 rpm and 4 mkg at 2300 rpm, and then the 1,650-pound vehicle would not have reached its maximum speed of 52 mph. At the time, Plymouth Savoy 19 CV could manage 75 mph at most, consuming double the amount of gas.

Friends helped me to get the body of the Anglia in shape too. It took several hands at the same time to put together a new headliner. These friends, all old classmates of my brother, graciously accepted me into their circle as a little outsider. They enjoyed coming to watch me at jam sessions while the jazz cellar was being expanded, but I was also made a member of the Eleonora Jazz Society, who had a vacancy for a slide trombonist. I loved the weekly jam sessions at the jazz cellar and our occasional performances in the student dorm, plus an appearance at the Federal Institute of Technology’s annual ball, the crowning moment of my musical career.

After a few excursions with my parents, I sold the Ford Anglia for a modest amount. I began to search for another car to fix, I came across a Citroën 11 Légère that jumped out of gear when driving downhill. The Citroën’s gearbox landed in the vegetable cellar just like the Anglia’s engine. To my great surprise, I had to build and borrow special tools beforehand to master its unconventional construction. I was very impressed by how the French engineers had broken away from orthodox constructions and taken a revolutionary new direction.

My day-to-day environment didn’t give me the same feeling. The vocational school expanded on middle-school students’ intellectual capabilities. At first I was simply bored, but in the end, I felt like I was in the wrong place. After two years, my parents allowed me to set a new course: I broke off my apprenticeship and enrolled at the Tschulok, a school to prepare for the high-school leaving certificate. My Citroën 11 Légère was running nicely and even looked good too. My mother sewed new upholstery covers to really put the cherry on top. It soon found a buyer, and the proceeds served to supplement my school fees, which were hefty for my parents. Friends kept entrusting me with their wheels for excursions as well as for all kinds of repair work, and my love for the legendary Citroën 11 stayed with me for a long time.

My road to school took me along Rämistrasse and past Café Morocco, which we called Marökkli. Musical philistines came here to search in vain for a Wurlitzer jukebox, but the waitress, Doris, was still in charge of choosing the LPs, from New Orleans jazz to swing. The regulars were mainly jazz fans. We’d often sit in a tight circle of ten or twelve around the small brass tables and listen to the newly bought records we’d recommended.

It took me two-and-a-half years to get ready for my high-school exam at the Tschulok. The teachers were so good at teaching us math and similar subjects that I managed to master them without doing much homework. However, what I was able to pick up in the foreign-language classes was far from sufficient to talk to the examiners about books or to write essays in English and French. In the fall of 1953, after completing the examination week, the examiners gave me their terse assessment: “Failed.” Now twenty years old and finally ready to try my hand at something that didn’t interest me, I stayed away from school and studied French and English words at home from morning to night, both languages at the same time of course. After some training, I managed to add a hundred new foreign words per day, and I could even recall them weeks later. Learning words in other languages became a fun hobby, and I felt brave enough to sit the exam again just six months later. To double my chances, I signed up for both the state exam and the federal one two weeks later.

The examination, both written and oral, included ten subjects and was in groups of four candidates took five days. One examiner accompanied the group from one exam to the next to get an overall idea of the individual candidates as well as our grades. I got the result I expected: I passed both exams, but both only just. So close, in fact, that one of the examiners advised me to reconsider whether I really wanted to go onto college. Well, that wasn’t my intention right away. My parents deserved a breather to only have to pay for one of their sons’ educations: my brother was already studying at the Federal Institute of Technology.

Instead I headed to the road traffic office to sit the commercial passenger transport test. I greeted the examiner standing beside a Citroën 11 Légère I’d borrowed from a friend. He took a seat in the back and asked to be driven to Eleonorenstrasse, a 650-foot-long alleyway. I had no need to consult the city map; I took the most direct route to the destination, home to the jazz cellar and the Eleonora Jazz Society. The examiner then told me to turn off the flat intersection road, Pestalozzistrasse, onto the steep Eleonorenstrasse and drive uphill, in reverse of course. The well-maintained Citroën managed it without even the slightest jolt. Once at the top, the examiner was satisfied and asked me to drive him back.

Two days later, I stood before a real Fröhlich taxi at the rank next to the Corso cinema, where the other drivers welcomed me as one of their own. In fact, I drove my taxi for a year and a half, interrupted only by my compulsory military service as I trained to the rank of artillery lieutenant. My passengers loved how I drove, especially the ones who were in a real hurry. At the time, Zurich didn’t have a speed limit. If there was high demand for taxis, I’d use the 100 hp (later 130) Plymouth Savoy limousines to take full advantage of the earning opportunities. In the following three-and-a-half years of my studies, I felt welcome as a part-time driver among my experienced colleagues.

At home, my room was not adorned with pictures of pin-up girls or film stars, but a large poster of the Manhattan skyline and a similar one of a DC4 cockpit. The former served to remind me: “If you can make it there, you can make it anywhere” (John Kander/Fred Ebb). I had the latter because I knew the functions of the individual elements from books and from lectures from pilots. I was fascinated by the automation of processes used very early in commercial aircraft, and quite simply by the fact that you could lift such huge weights thousands of feet into the sky and keep them there for hours.

My desire to attend flying classes came as no surprise to my parents. However, it took them a few days before they agreed to give the written consent I asked them for. Their friends, Mr. and Mrs. Müggler, helped them to come to the decision. Their son was serving in the air force as a drill officer and flight instructor. I soon received an invitation from him. He remembered me despite the large age gap between us and wanted to give me advice on the path I wanted to take.

We were all shocked when Captain Müggler crashed before we were able to meet up. The tragic accident didn’t stop me, but the Aviation Medical Center in Dübendorf did. The doctor considered my tonsils to be too large and my eyesight—ascertained with the help of an E chart—to be barely good enough. I hunted down the same E chart at the specialty store, bought it, and memorized all the games. I also had my tonsils taken out and took the medical again, this time for the recruiting school with the flying squad. An experiment was being carried out at the Aviation Medical Center: testing eyesight in a darkroom. With this novel way of testing, unfortunately mine was now just below the limit.

A little later, my service history fluttered through the letterbox. It read: “Artillery branch, promoted as a motorist.” Out of the question. My past working with cars had caught up with me. After all, the Saurer M6, the vehicle used to transport 10.5 cm guns, still had a CT1D engine.

After my first three months as a taxi driver, it was time for me to head to the summer cadet school at the Monte Ceneri artillery base. Upon entering, the school commander redistributed me from the motorcyclists to the gunners at my request. A lot of people thought I was crazy. How could anyone spurn a division that was so coveted at the time? I wasn’t tall enough to position guns and lug around and load ammunition. However, my crew soon realized that I knew how to aim quickly and flawlessly, and were happy to leave the position at the gun to me whenever they could. All the more so given that there was a threat of arrest as punishment for aiming errors.

My mental fitness was also later deemed better than my physical fitness. I’d barely arrived in the Heavy Artillery Battery Model60 officer corps when the battalion commander asked me to attend a two-week advanced shooting course with a view to a planned deployment as the battalion’s fire direction officer. I then commanded a unit of eighteen guns with a deputy and five soldiers. To do this, the target coordinates were added to the guns as settings with the help of a ballistics calculator and two correction calculators. The elements were not calculated mathematically, but purely graphically. To enable my crew to work quickly and accurately, neon tubes—fed by a remote emergency generator—hung in my fire-direction tent instead of oil lamps. Every senior officer who came to inspect our battalion did not hesitate to visit the “lunatic” in the brightly lit tent.

Alongside an ideal environment, good performance was mainly based on intensive training. The battalion commander gave us the time we needed again and again, even if that meant deviating from the order of the day. For example, when Division Commander von Sprecher ordered two bivvy nights, the battalion commander’s instructions read: “Intelligence does not camp.” This order enabled us to create the safety cards for the early-morning shooting in our barracks room instead of out in the field. It was a great honor when the department commander requested that I lead the battalion’s fire-direction center for two more years beyond the official exit age. Seven years was enough for me, though. I’d always believed that an academic career should be complemented by a military one wherever possible, at least to the rank of junior officer, and I’d accomplished that. I was discharged from the artillery division at the end of 1966.

As a member of the Artillery College, though, I continued to take part in the public mortar shooting in Zurich well beyond the year 2000. I scored a direct hit as a guest, and the president handed me the Artillery College’s coveted silver cup at the subsequent awards ceremony. I gave this extremely rare cup to our son Peter, whose career as chief of artillery in the staff of an infantry brigade reached the highest rank achievable for a militia officer.

***

Back to the Marökkli, though. In the spring of 1955, between earning the rank of non-commissioned officer and starting my officer training, I drove a taxi for ten weeks. This gave me a lot of time to enjoy music and meet with friends at the Marökkli. A bunch of business-school students regularly used the hours between classes for a chat and a cup of coffee in “our cafe” and over time became regulars. How this little group came to be a part of ours eludes my memory. It certainly wasn’t thanks to my shyness. God simply placed a charming creature by the name of Christine at my side, who I found myself greatly attracted to. Christine looked me up and down without her face darkening—on the contrary, in fact. That meant a green light for me to seek her company and a green light for her to start remodeling me. Incidentally, it was a conversion that lasted many years and contributed a great deal to my personal development.

After officer training at the end of October 1955, I took up a place studying at the Federal Institute of Technology’s Department of Electrical Engineering in Zurich, following my brother’s urgent recommendation. Whenever I could, I preferred meeting Christine to attending my lectures. We saw each other very often, if not daily. She was seventeen; her parents kept a close eye on her and didn’t allow her to go out in the evening—except for concerts by the Tonhalle Orchestra. So I, too, developed a love of classical music as the only way of spending an evening with Christine. I was gripped by the fascination of finding out everything about a person who made everything just feel right. The hope of having found the perfect life partner increasingly turned into a certainty. Christine took a fraction of a second to say yes to my marriage proposal, which I launched at her quite early on. Touched by fortune for the second time in my life, I felt extremely blessed. Christine’s father, on the other hand, felt my happiness was a great misfortune for his daughter and he kept trying to change the situation around. The effort to save his daughter ultimately culminated in him attempting to ban us from meeting at all, as well as in demanding we sold the car that we were already sharing. It was a beautiful, four-seater Hillman Minx Cabriolet, green in color, that I made roadworthy and was for a long time a thorn in his side as a symbol of the connection between Christine and me. We decided to respect her father’s demands and stuck to them. Three months later, we celebrated Christine’s twentieth birthday at the same time as our engagement with all our friends, along with an announcement we made to the entire family.

***

The idea that the Federal Institute of Technology was much stricter than a university turned out to be unfounded. Most of the lectures were also made available in printed form, meaning there was no need to attend them. With knowledge acquired through self-study, I performed better in exams than with vague knowledge topped up with lecture notes. My favorite music sounded in my room without interruption as I studied. I couldn’t even hear the music when I was fully focused. When my focus faltered, I’d consciously listen to the music so as not to let another thought arise in my head. So, after a few bars, maybe even a whole piece, I managed to make the music disappear again. Despite—or perhaps because of—the little time I had to prepare, I achieved strong results with both pre-diplomas and the final diploma.

I took my brother’s advice and headed into uncharted territory when choosing my diploma thesis. It was 1959 and the task was to design and build an ironless audio-output stage with transistors. At the time, the Federal Institute of Technology provided very little teaching regarding transistors. My brother passed me the books I needed and an hour later traveled abroad on business for a few weeks. I quickly got to work putting the theory into practice. Hangers crept in due to my insufficient experience in metrology. In the eighth and final semester, unfortunately the opportunity to acquire the necessary equipment was optional. In the end, I succeeded in demonstrating a perfectly functioning output stage to Prof. Weber. Only there was too little time left to prepare the documentation, despite two nights spent working at the typewriter with Christine. Unfortunately, I was no longer able to incorporate all my findings, but it was enough for a grade of five out of a possible six.

***

My parents—my father aged fifty-two and my mother aged forty-nine—bought their first car a few months before I graduated from the Federal Institute of Technology and went on vacation together for the first time. They were able to enjoy their successful commitment with full mental vigor for many years. My father died in 1989 at the age of eighty-nine, and my mother got to the end of her ninetieth year.

***

Christmas was coming up, Christine and I were happy, and we were looking forward to a new phase in our life, with the poignant words of pianist James P. Johnson in our minds:

“If I could be with you (one li’l hour tonight).”

At the beginning of January 1960, I joined the development team at Standard Telephon und Radio AG (STR) in Zurich, and ever since then, I have been involved in developing products that either directly or indirectly help people to communicate.

Toward the end of March, an apartment with a direct bus connection to STR was vacated in Rüschlikon. On March 31, 1960, Christine’s father reluctantly accompanied the twenty-one-year-old bride to the altar in the old church in Wollishofen. At the wedding breakfast, the father of the bride emphasized my stubbornness in his speech. I came to the realization that I think in a different way from many and continue to pursue realistic goals even when others have long since given up. After that I often thought of my father-in-law when I was successful, but also when I was defeated. I’ve always moved forward in small steps in an effort to achieve great landmarks, but never quite made it.

Our honeymoon took us to the Riviera dei Fiori in Italy, where I saw the sea for the first time in my life. We enjoyed our first vacation together.

My wife Christine, just married.

Children came soon after. Our daughter Barbara was born a good ten months after the wedding, our son Michael another seventeen months later, and just fourteen months later our second daughter Katharina—in theory our last child.

In the following seven years, we spent our vacations and often weekends too, ideally extended ones, in Origlio, at Christine’s parents’ vacation home. The huge rustic building had a paved driveway and a forecourt, and its park-like forest, flat meadow, and vineyard offered the children plenty of places to play, whether tricycle, hide and seek, or badminton. A paradise for the little ones, and something almost like a vacation for their mother. Spending our vacations in a hotel was out of our reach financially at the time.

My task at STR was to develop a secondary-group 1–21 auxiliary amplifier, that is, an amplifier to simultaneously transmit 1,200 telephone calls via a coaxial copper cable. The useful bandwidth was around 6 MHz, and the one in the loop up to the return of the gain to 0 to Nyquist 12 MHz. Pipes could easily handle this bandwidth; transistors couldn’t yet. After developing transistorized amplifier for carrier-frequency technology, I moved from STR to Philips AG in Zurich on March 1, 1962. My employment reference from STR read:

“Mr. Schmid has thoroughly familiarized himself with the development problems, and has very keenly recognized and mastered decisive difficulties of a theoretical and metrological nature.”

Maybe I could make something of myself after all! The art of engineering is not to be gripped by irrelevant matters, but to spend as much of your time as possible solving important problems and, especially in triage, not messing up on a small or large scale.

At Philips AG Zurich, I joined a group of seven employees who developed products for PTT (“Postal, Telegraph, and Telephone,” later Swisscom) as well as adaptations for building Dutch equipment into the Swiss network. Soon appointed head of the group, I was also responsible for explaining our work, which led to frequent contact with customers.