5,91 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: STORGY Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

“Sian Hughes’ delightful imagination and technical talent makes each story a unique treat.”

– Boyd Clack –

Creator of High Hopes and Satellite City

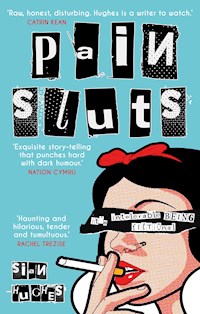

A teenager performs stripteases in her bedroom window as funeral processions pass by. A grieving mother reunites with her miscarried foetus. A widow takes on the sinister, rapacious treehouse in next door’s garden. Combining pitch-perfect, darkly comic observations with tender touches of humanity, Pain Sluts chronicles the flaws, frailties, and enduring spirit of an eclectic cast of curious characters as they navigate threats to their identity and humanity.

A brave and bold literary debut bursting with calamity and compassion, Pain Sluts is an astonishing collection of stories which lays bare our beauty and bizarreness. Laden with love, loss and longing, this book illuminates Sian’s extraordinary ability to create believable characters that brave our brittle world, often in outlandish or unusual ways. Sharp and tender, true and wise, these stories announce the arrival of a uniquely talented new voice in British fiction.

“Sian Hughes writes her characters with love and warmth, dissecting their complex inner lives with beautiful and profound prose. The stories are raw, honest, sometimes disturbing, capturing the enormity of tiny moments and the extraordinariness of ordinary people. Written with a dark humour and an exquisite attention to detail, the stories linger, unfolding in the mind, long after the book has been closed. Hughes is clearly a writer to watch.”

– Catrin Kean –

Author of Salt

Winner of Wales Book of the Year 2021

“Sian Hughes is an immaculate stylist, and Pain Sluts is one exquisite and harrowing revelation after another. In this magnificent collection, Hughes claims a darkly radiant fictional territory that is all her own.”

– Anthony Trevelyan –

Author of The Weightless World

Longlisted for the 2016 Desmond Elliott Prize

“In this wonderfully visceral collection, with its echoes of AM Homes and the early transgressive short stories of Ian McEwan, Sian Hughes has fashioned her own brand of distinctly South Walian Gothic, full of bodies and their bloody mysteries, people and their hidden perverse selves.”

– John Williams –

Author of The Cardiff Trilogy

“Haunting and hilarious, tender and tumultuous. A bold and original collection that depicts life for women in contemporary south Wales in all its mundanity and quirkiness. Thrills from beginning to end.”

– Rachel Trezise –

Author of Fresh Apples and Easy Meat

Winner of the inaugural 2006 Dylan Thomas Prize

“Sian Hughes shares Thomas Morris’ skill of evoking the everyday, the ordinary, and the potentially banal in warm, three-dimensional technicolour. Her characters stand up, speak, and walk off the page to inhabit your mind. The stories in Pain Sluts are not easily forgotten.”

– Sonia Hope –

Jerwood/Arvon Mentee and Guardian 4th Estate BAME Short Story Prize Finalist

Sian Hughes is a freelance copywriter, screenwriter, and author whose short stories have been published online and in print and adapted for film and TV, appearing on HTV, BBC Wales, and S4C. An adaptation of her short story ‘Consumed’, starring ‘The Descent’s’ Shauna Macdonald, was premiered in 2021 at the Glasgow Short Film Festival. Having recently completed an MA in Creative Writing, for which she gained a Distinction, Sian also works as a creative practitioner for the Arts Council of Wales. Sian lives in Cardiff with her husband, three children, and a menagerie of wayward animals.

sianhughes.me.co.uk

@flossingthecat

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 247

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

“Sian Hughes’ delightful imagination and technical talent makes each story a unique treat.”

– Boyd Clack –

Creator of High Hopes and Satellite City

“Sian Hughes is an immaculate stylist, and Pain Sluts is one exquisite and harrowing revelation after another. In this magnificent collection, Hughes claims a darkly radiant fictional territory that is all her own.”

– Anthony Trevelyan –

Author of The Weightless World

Longlisted for the 2016 Desmond Elliott Prize

“In this wonderfully visceral collection, with its echoes of AM Homes and the early transgressive short stories of Ian McEwan, Sian Hughes has fashioned her own brand of distinctly South Walian Gothic, full of bodies and their bloody mysteries, people and their hidden perverse selves.”

– John Williams –

Author of The Cardiff Trilogy

“Haunting and hilarious, tender and tumultuous. A bold and original collection that depicts life for women in contemporary south Wales in all its mundanity and quirkiness. Thrills from beginning to end.”

– Rachel Trezise –

Author of Fresh Apples and Easy Meat

Winner of the inaugural 2006 Dylan Thomas Prize

“Sian Hughes writes her characters with love and warmth, dissecting their complex inner lives with beautiful and profound prose. The stories are raw, honest, sometimes disturbing, capturing the enormity of tiny moments and the extraordinariness of ordinary people. Written with a dark humour and an exquisite attention to detail, the stories linger, unfolding in the mind, long after the book has been closed. Hughes is clearly a writer to watch.”

– Catrin Kean –

Author of Salt

Winner of Wales Book of the Year 2021

“Sian Hughes shares Thomas Morris’ skill of evoking the everyday, the ordinary, and the potentially banal in warm, three-dimensional technicolour. Her characters stand up, speak, and walk off the page to inhabit your mind. The stories in Pain Sluts are not easily forgotten.”

– Sonia Hope –

Jerwood/Arvon Mentee and Guardian 4th Estate BAME Short Story Prize Finalist

“At a time when, understandably, we’re looking for things to distract us from reality, these stories remind us that there can be beauty, hope, laughter, even inspiration in the everyday. The characters presented in Pain Sluts are full of defiance and a fierce determination not to be overwhelmed by the slings and arrows. A great collection from an author who’s clearly set for big things.”

– Stephen Thompson –

Author of Toy Soldiers and No More Heroes

“With its combination of lyrical prose and brutally honest portraits of humanity, Sian Hughes’ Pain Sluts recalls Annie Proulx at her best. Punctured with dark wit and fleeting moments of tenderness, this is a collection that delivers knockout blows on every page. Wise, raw, and masterfully sculpted.”

– Tomas Marcantonio –

Author of This Ragged, Wastrel Thing and Flamingo Mist

“Rich, dark, bitter and exquisite, this collection definitely packs a hoofing chilli kick. Whether tackling the groaning familiarity of sexual harassment, or the generational abyss of understanding between a mother and her daughter, or the unexpectedly deft act of revenge of a sweet and ignorable widow, the reality of loneliness or the tragedy of watching someone disappear into dementia, each story punches hard with dark humour, surprise and minute observation. A brave & bold literary debut.”

– Nation Cymru –

STORGY® Ltd.

London, United Kingdom,

2021

First Published in Great Britain in 2021

by STORGY® Books

Copyright SIAN HUGHES © 2021

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the following publications in which some of these stories were first published: Scribble Magazine, ‘God and the Runt’; STORGY Magazine, ‘Shaving for Dog’, ‘Death and the Teenage Stripper’, ‘Consumed’ (first published as ‘Can You Eat the Wind?); STORGY Books, ‘Trevor’s Lost Glasses’; The Fiction Pool, ‘Werewolf’.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the express permission of the publisher.

Published by STORGY® BOOKS Ltd.

London, United Kingdom, 2021

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Cover Design by Dean Cavanagh & Tomek Dzido

Edited & Typeset by Tomek Dzido

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

Trade Paperback ISBN 978-1-9163258-4-5

eBook ISBN 978-1-9163258-5-2

www.storgy.com

Also available from STORGY Books:

Exit Earth

Shallow Creek

Hopeful Monsters

You Are Not Alone

This Ragged, Wastrel Thing

Annihilation Radiation

Parade

To Philip,

for always believing.

Contents

Epigraph

Consumed

Werewolf

Brontosaurus

Broad Money

God And The Runt

Dead in a Good Way

Trevor’s Lost Glasses

Pain Sluts

01000101 01110100 01101000 01100001 01101110

Death And The Teenage Stripper

Ysgyryd

Rattus Rattus

Shaving for Dog

Life is Not a Bunch of Fucking Roses

Metastasised

Backsliders

Terminal Velocity

Cannibal

Monstrosity on Stilts

Sian Hughes

Acknowledgements

Coming Soon

Coming Soon

STORGY Magazine

Tell all the truth but tell it Slant -

— Emily Dickinson

Sometimes it feels like we are only this: moments of knowing and unknowing one another. A sound that is foreign until it’s familiar. A drill that’s a scream until it’s a drill. Sometimes it’s nothing more than piecing together the ways in which our hearts have all broken over the same moments, but in different places. But that’s romantic. Sometimes it’s realer than that.

— T Kira Madden

Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls

And I wonder about

this lifetime with myself,

this dream I’m living.

I could eat the sky

like an apple

but I’d rather

ask the first star:

why am I here?

why do I live in this house?

who’s responsible?

eh?

— Anne Sexton

The Fury of Sunsets

‘You haven’t lost the pregnancy. But I can’t find a heartbeat.’

The sonographer’s sentences don’t belong together. Scanning her face for more clues, Amy notices that she has a tan face and white neck, like parts from different bodies.

‘Can I see?’ she says.

The sonographer points at the screen. In a corner of Amy’s womb, floating with its back to her, in sulky suspended animation, is a shape.

‘There’s the blood flow from the placenta,’ the sonographer says, as a tide of grainy darkness flows in from the edge. ‘But there’s no fetal heartbeat.’

The sonographer continues to circle the image, shaking her head. It occurs to Amy that it could all be a problem of technology: a mouse that doesn’t work, a frozen cursor. But when a nurse standing next to the cubicle’s curtains leaves suddenly, Amy knows it isn’t that. And yet she is still confused. The baby is gone but not gone. It is an anomaly Amy can’t process, like seeing the light from a dead star.

‘I’ll get the doctor,’ says the sonographer.

On Saturday evening Amy bleeds. A pink-gray embryo sac falls onto the stained gusset of her knickers.

She shouts for Rob three times.

‘You need to calm down,’ says Rob, walking into the bathroom finally. ‘Connie’ll freak out.’

Even though Amy loves her stepdaughter: Connie with the jagged shoulder blades that stick out like wings; Connie who says spaghetti with ‘daleks’ instead of spaghetti with garlic; a sudden hatred for her husband works itself through Amy’s body like a contraction. Through the skin of the embryo sac, the blurry outline of something emerges.

‘I’ll get towels,’ says Rob, looking away.

Amy doesn’t know what to do with the embryo sac. Flushing it down the toilet as if it’s a goldfish or shit is unthinkable. Interring it in the freezer seems worse. Wrapping it in a parcel of quilted toilet paper, Amy stuffs it in her dressing gown pocket.

‘I don’t know what to do with it,’ she says to Rob, as they’re watching a Netflix thriller later.

Amy has begun to picture the baby drying inside the toilet paper like snot: the paper sticking to the surface of the sac.

‘Bury it,’ says Rob, and then, out of the blue, as cops drag a dead girl out of a lake, ‘Can’t help thinking you’re enjoying this.’

‘Fuck you,’ she says, storming to the kitchen.

In the kitchen, Amy studies the spice jars on the rack. Emptying the contents of the fenugreek jar into the compost caddy, she fills it with oil. There is a tremor, a kind of convulsion, as she drops the sac into the oil. The sac spreads and expands in the fluid. Amy sees the beginnings of legs, a spine curling inwards like a comma, a single eye meeting hers.

‘Hi little one,’ she says.

‘Sorry about last night,’ says Rob, the following morning. ‘Guess I freaked out.’

Amy clasps her fingers around the jar inside her dressing gown as if it were a secret.

‘I’m fine Rob,’ she says.

‘I’ll try to be back by lunch,’ he says. ‘We could go out?’

Amy pushes the jar deeper into the pocket of her gown, careful not to push it through a tear in the seam that was once a slit but is now a gaping hole.

‘Maybe,’ she says, pulling the belt of her dressing gown tighter. ‘If you’re back.’

After Rob has left, Amy relocates the spice jar to the drawer of her nightstand. Every hour, on the hour, she climbs upstairs, as if she were visiting somebody in hospital. By eleven the egg sac is unravelling: silky fibres unwrap themselves from around the baby’s torso, giving the impression of somebody undressing.

Amy covers the jar in a tea towel.

At midday, Amy collects Connie from nursery, takes her to the park around the corner. Connie plays in the bushes behind the perimeter railings, pretending to be a zookeeper looking for a lost lion. A strong wind blows in from the west.

‘Can you eat the wind?’ says Connie, running over to Amy’s bench.

Amy normally likes the weird things Connie says. But today Amy is desperate to return to the other child. She has remembered a story about a friend of her great auntie Edie’s, Beattie Bevan, who kept a baby in ethyl alcohol on her dresser.

‘Let’s go home shall we?’ says Amy. ‘It’s getting cold.’

Settling Connie in front of the television, Amy checks in on the baby. Apart from a few shreds of egg sac, stuck to his forehead like transfers, the baby is naked. Waxy strips float to the surface of the oil.

Amy googles ‘how to preserve a foetus’. Her search returns a Daily Mail story about a mother who kept a foetus in an ice cube tray in a freezer, You Tube videos about preserving chicken embryos in acrylic.

At two, Rob calls to say he’s stuck at work.

‘Wasn’t expecting you anyway,’ says Amy.

‘Oh, ok’ he replies. ‘How’s the bleeding?’

It’s the first time Rob has asked about the bleeding. Amy knows she should be grateful. But Amy doesn’t give a fuck about the bleeding. She only gives a fuck about the baby. If anything, she likes the way the bleeding has left her feeling light-headed and insubstantial. The fact Rob knows so little about her dredges up the bitterness she so often feels.

‘I got blood on the Ercol,’ she says. ‘It won’t come off.’

The Ercol chair is Rob’s prize possession. Amy is pleased that she bled on it.

‘Fucksakes,’ he says.

When Rob gets home, Amy makes her excuses and retires early to bed. Having repositioned the jar under her pillow for safekeeping, she tries to sleep. The edge of the jar presses through the pillow into her cheek, carving out nightmares. When she wakes, it is to the idea that someone has stolen the baby. She yanks the jar from under the pillow.

The egg sac has completely disintegrated; remains hang down from the surface in an assortment of gray and white tatters like bunting. Amy resists the urge to shake the jar like a snow globe to bring it back to life. At the same time, the baby is as beautiful as ever. Following the contours of its body, Amy sees the head bent over onto the chest as if in prayer; tiny mounds where there would have been ears; the suggestion of toes.

‘Rob!’ she calls.

Rob is asleep in the guest bedroom, one leg poking out of the duvet.

‘Rob!’ she says again. ‘I need to show you.’

Putting the jar on the nightstand beside him, Amy turns on the lamp. The baby glows orange between them. Amy counts the stitches under Rob’s left nipple as she waits for him to respond. There are meant to be nine stitches, but she can only count seven.

‘You need to see a therapist Amy,’ he says, finally. ‘It’s not normal.’

A wave of loneliness hits her with such force she almost loses her balance. She grabs the jar from the nightstand.

‘We lost another baby, and you couldn’t give a fuck.’

Afterwards, Amy sits on the toilet lid in the bathroom, waiting for the morning, for normality, for something. She imagines sitting on the toilet lid for hours and days and months, watching her face age in tiny increments in the mirror. At the same time, she wants things to return to normal. To start over. It troubles her that she can’t remember the number of stitches on her husband’s body.

Taking the jar from the pocket of her dressing gown, which feels heavier now, weighted, Amy stares at the baby, who has his back turned. Suddenly she wants the baby back inside her, where it belongs. She wants him alive again, like he was in the sonographer’s office, to exist in space, if not in time, like stone babies fossilized inside their mother’s abdomens.

Tipping it out of the jar into her palm and lifting it to her face, Amy strokes the tiny body, a final caress from crown to rump, before swallowing her baby whole.

Today’s lovers are even closer to Angela’s house than usual, their Kia Picanto squeezed into a triangle of tarmac where Lovers Layby tails off.

Angela puts the cleaning cloth on the windowsill, as a bilious, clawing sensation rises in her. The heat generated by the lovers seems to have passed through her skin to the core of her. She screws down the cap on the Windolene.

‘This can’t go on, Pete!’ she yells. ‘It’s disgusting.’

Pete is watching tele in the conservatory, wearing his noise cancelling headphones, which silence ninety percent of ambient noise. Last week, over dinner, he claimed they made him feel like an astronaut in outer space.

‘Oh forget it!’ says Angela.

Angela knocks on Val’s old house at number one. In her hand is the petition she’s written.

As she waits for her new neighbour, Mira, to appear, Angela’s attention shifts to a midi-skip spewing out carpets on the drive: rolls of Axminster that were once Val’s pride and joy.

‘C’mon Ange, we were all young once!’ Mira says, when Angela shows her the petition calling on the Council to install CCTV on the cemetery gates overlooking Lovers Layby. ‘They’re not doing any harm.’

Angela doesn’t like Mira. She doesn’t like being called Ange, which sounds like a nasty germ-laden sneeze. She doesn’t like the fact Mira and her partner Mike (a hedge fund manager with an accent Angela can’t place), are slowly erasing her memories of Val, so much so that Angela finds herself questioning whether Val even lived at number one, or whether she always lived in The Burrows nursing home, in a room so small they put her wardrobe in the bathroom.

‘I wrote it myself. Took me all night,’ she says. ‘Val would have felt the same.’

‘I’m sorry,’ Mira says.

Martin at number three is more understanding.

‘It’s not just couples, Angela,’ he says. ‘Last week I saw a man masturbate. He was in a green Ford Sierra.’

Martin’s lips have an ashy bluish tinge that suggests he has a heart condition. Angela wonders whether Martin’s increasingly crude language is symptomatic of his illness.

‘Legally, masturbating in broad daylight is an act of gross indecency,’ he whispers. ‘I saw him ejaculate.’

The explosive ‘j’ and ‘t’ consonants in ‘ejaculate’ send flecks of dense creamy spittle into Angela’s décolletage.

‘So will you sign the petition?’ says Angela, stepping back.

‘I don’t like CCTV,’ says Martin. ‘But if you need to talk, I’m always here.’

‘Martin thinks it could be against the law—all those shenanigans in the layby,’ Angela says to Pete when she gets home. ‘Gross indecency,’ he said.

‘Then ask Martin to deal with it,’ he says. ‘He likes doing you favours.’

Last time Pete was away on business, Martin had wheeled their bins up the drive. Angela was on the phone to Talk Talk at the time, arguing over a mid-contract price hike, when she felt a tap on her shoulder.

‘I put the bins out, but the pin’s gone.’

Martin was behind her on the welcome mat, holding up the broken lid of their wheelie bin like a trophy.

‘Long screw’s what you need Angela,’ he said. ‘Then bob’s your uncle.’

Maggots wriggled on the hinge of the bin lid. A shift in air density made it harder to breathe.

‘A long screw and a bottle cap works a treat.’

‘I’m on the phone Martin,’ she’d said. ‘I’ll deal with it later. Thank you.’

Martin drew his hand away, his thumb grazing Angela’s bosom by mistake. A maggot tumbled downwards like confetti. Later, when Angela told Pete about the incident, she added details. Martin skimmed her nipple and breast, she said. Her nipple was erect from the draught.

‘Huh. Say what you like about Martin. Least he doesn’t spend all day wallowing about in his La-Z-Boy watching rubbish on TV,’ she says.

‘Too busy being a peeping Tom,’ says Pete, reaching for his neck brace, which Angela knows he only wears to avoid intimacy.

‘Carry on like that and you won’t be able to hold yourself up!’ says Angela. ‘Physio insists you don’t need it.’

‘Physio’s even more of a prick than Martin,’ says Pete.

Angela takes the layby petition with her to The Burrows for her weekly visit to Val.

When she gets there, the nursing home is hosting a party to celebrate the completion of the sun patio. There are jam sandwiches, chocolate fingers, French fancies. Shafts of sunlight pour in through the new bi-fold doors, lighting up Val’s cheek.

‘It’s like Sodom and Gomorrah in the layby now,’ says Angela, handing Val the petition. ‘You wouldn’t believe what they get up to. Ych a fi.’

‘It’s a re-le-vation,’ says Val, squinting at the petition. ‘I can see so much better without my glasses. You have to work harder but at least everything isn’t jumping out at you.’

‘Mira won’t sign it,’ says Angela. ‘Too busy tearing your carpets out.’

Val finishes the doughnut that’s been balancing on the arm of her chair. Another resident lifts one half of a turtleneck jumper, revealing a breast shaped like a scythe.

‘Nobody wants to see your boobies Betty!’ says a care worker, running over.

‘They’re being over-stimulated!’ says Angela. ‘Too much sugar.’

Val shakes her head in disagreement, causing custard to zigzag through her chin hairs.

Angela swabs at Val’s face with a wet wipe.

‘Bloody hated those carpets anyway,’ says Val, flinging the petition to the floor. ‘All the swirls gave me migraines. I used to think about ramming the house down with the fucking car.’

Before coming to The Burrows, Val never used the word fuck. The word fuck distresses Angela. She pictures Val ramming the door of number one with her Allegro; the bonnet crashing into Mira’s new Corian kitchen island.

‘I’ll bring it back next week,’ says Angela, peeling the petition from the floor. ‘There’ll be fewer distractions.’

Angela kisses Val goodbye on the cheek. Val’s thickly applied face powder leaves a residue like animal down on Angela’s lips.

‘You used to be a werewolf,’ says Val, inexplicably.

‘Get some rest please Val,’ says Angela.

Pete has made chicken dinner by the time Angela arrives home.

‘I been thinking,’ he says, plating up. ‘There was a notice on the community board about a book club. First Tuesday every month. You could do with an outlet.’

‘I’ve gone off books,’ says Angela.

Angela likes books, but not as much as she used to. She is angry with Pete for always assuming he knows what she needs, when the truth is, he hasn’t a clue.

‘Books don’t do it for me.’

Angela scrapes chicken leftovers into the recycling caddy under the sink, her ass pointing at Pete like a gun.

‘Val told me I used to be a werewolf,’ she says. ‘I think she’s got dementia. Or a tumour.’

‘A werewolf?’ says Pete.

Angela imagines Pete hoisting up her skirt, parting her ass cheeks. When she stands up to straighten her skirt, a pea lands on the tiles between her feet. Angela crushes the pea into the grouting until it’s dead. Why should she pick it up, or talk, or do anything, when Pete doesn’t even notice when her ass is as engorged as those pink mandrill asses on nature programmes?

‘Is there something wrong?’ says Pete.

‘I’m fine thank you Peter,’ says Angela.

Angela wanders around the house doing nothing. Pottering around, dilly dallying, going to waste. She sorts through the clothes that need donating, throwing them back in the wardrobe in a heap. She reads the blurb and a few pages of her thriller. At some point it occurs to her she might be coming down with something: a chill, a foreign virus, the C word.

As she’s passing the staircase window on her way to bed, a black Audi pulls into Lovers Layby. The driver eases his seat back, sending a creaky shiver through Angela’s solar plexus.

‘We should never try to deny the beast—the animal within us,’ says a voice.

Pete is in the hallway by the console table, wearing a werewolf mask.

‘The Howling, 1981,’ he says. ‘Classic.’

‘What the hell are you playing at?’ says Angela. ‘You trying to kill me?’

Pete takes a step towards Angela, tugging off an all-over latex mask with protruding muzzle, matted faux hair, yellow fangs with fake tartar and blood.

‘Don’t you remember? Derek gave it to us. When he shut down the fancy-dress stall. You wore it to that Halloween party in Caldicot. Val came. And Alan. That’s what she was on about today.’

Pete throws the mask into the under-stairs cupboard.

‘Thought wearing it would jog your memory,’ he says, demoralised.

‘God knows what you’re talking about,’ says Angela. ‘You’re as senile as Val.’

That night, Angela dreams she is trapped in a layby: a sweeping semi-circle of tarmac that has no function because the carriageway is already wide enough. She and Peter are in their old car. The Cavalier. Pete is on top of her, dead. In her panic, she knocks off the hand brake. The car lurches like a ghost car towards the carriageway.

Going downstairs, she finds Pete lying on his stomach on the wicker sofa in the conservatory, arms wrapped around a queer-smelling cushion.

‘I’m coming now,’ he says, half-asleep.

‘You were snoring again,’ she says. ‘I could hear you through the ceiling like a dog.’

‘That’s impossible. I’ve been awake this whole time.’

Angela pictures severing Pete’s dangling uvula with nail scissors to stop him snoring. Suffocating him with the orthopaedic memory foam pillow from JML. Leaving him. Lying beside him, huffing loudly, she tugs a throw across the scrag ends of her knees.

‘I thought you should know,’ she says. ‘I remember the party.’

‘Oh,’ he says. ‘Ok.’

After the layby dream, there’d been a second dream; though it wasn’t a dream but a memory. She and Pete were on their way back from the Halloween party in Caldicot. They’d stopped at a service station in a rest area for lorries. Pete used the sheet of his ghost costume to cover the stick between the seats. It was the best sex she’d ever had.

‘It was fun,’ she says. ‘We used to have fun Pete.’

‘We were young. I’m sixty-one.’

‘I know. It’s not really your fault.’

The werewolf mask is resting on top of Pete’s toolbox in the under-stairs cupboard when Angela retrieves it in the morning.

Sniffing at the guard hairs and lining, Angela tugs the mask over her head. Through the eye-holes the hall is unfamiliar, as though she’s trespassing through somebody’s house.

Back upstairs she uses a clothes brush to smooth the hair down, spraying tingly clouds of cherry-scented dry shampoo into the pale grey under-fur, removing the dust with a wet wipe. Without thinking, she begins to peel off her clothes.

When she’s naked, except for the mask, she checks her reflection in the mirrored wardrobe doors, adjusting their angles until she appears as a series of infinite indestructible reflections, stretching backwards and forwards in space.

The white-grey werewolf fur falls into the dipped curves of her collarbone, framing her breasts, contrasting with the glossy dark bird’s nest of her pubes. Lifting her forearm to the muzzle, she tastes the luscious long-forgotten saltiness of her flesh.

Afterwards she visits Val at the nursing home.

‘Hope to Christ you haven’t brought that Ryvita muck again,’ says Val.

Val has a condition called late-onset Type 1 diabetes. As a rule, Angela brings a selection of healthy snacks to the nursing home: crackers, easy-peel oranges, sugar-free jelly pots, water. But today she has brought other things. A multipack of Twix, two blue Monster drinks, a dragon fruit that was on sale in the reduced aisle.

Val sucks the Twix like it’s a drug.

‘I want to die happy. Slip into a diabetic coma,’ she says. ‘I can’t go back.’

‘Don’t know what came over me,’ says Angela.

Angela pulls the mask from her carrier bag.

‘Here’s that werewolf you were talking about,’ she says, placing it next to the Twix pack and dragon fruit on Val’s over-chair tray table. ‘It was a Hallowe’en party we went to in Caldicot. You and Alan came. That’s the mask I wore.’

Val strokes the fur on the muzzle, her lips lined theatrically with chocolate.

‘You had a tail hanging from your pussy like a cock,’ she says.

Earlier, whilst wearing the werewolf mask, Angela had masturbated in the guest room, as rays of late afternoon sunshine swished across her ass, her naked haunch. In the mask, she felt more like herself.

‘What was I?’ says Val, quite suddenly. ‘I can’t remember.’

Val holds the mask to her face, inhaling deeply.

Angela takes the mask from Val’s hand. Val clamps her hand to Angela’s wrist.

‘Who was I at the party?’ she says. ‘Who was I?

In the evening, when a Honda Civic pulls into Lovers Layby, Angela reaches for Pete’s woollen greatcoat from the banister, which still smells of Aramis from years back.

‘I’m going for a walk,’ she shouts. ‘Won’t be long.’

Light filters through the blinds in Martin’s study as Angela passes number three. A grinning Martin peers through a fissure in his blinds, his shirtless torso glowing eerily. Fondling the rough hairs of the werewolf mask she secreted earlier in Pete’s pocket, Angela follows the curve of the pavement around the cul-de-sac’s turning circle, until she’s on the same side of the road as the layby.

The Honda is parked at a skewed angle to the pavement as though abandoned. Keeping to the shadow of the wall, Angela pulls on the werewolf mask. Walking purposefully towards the car, as her skin fuses to the latex of the mask, she creeps on bended knees along the Honda’s nearside.

At first, she sees nothing except limbs. A low-resolution assortment of parts splayed unnaturally across the front seats. She knocks on the passenger window. But the music, a house remix of something she once knew, renders the knocking inaudible, and for a moment she wonders how loud the music would need to be to crack all the windows in the cul-de-sac, to penetrate Pete’s foam cocoon.

She knocks a second time, then a third, rapping hard on the glass with her wedding ring. The woman in the passenger seat turns her head in slow motion, owl-like. Imperfectly blended lines of shimmering cream highlighter map the outer edges of her cheekbones, the ridge of her nose; streaks of gold fizz like comets through her hair. Angela can barely bear it: this beauty.

‘You shouldn’t be here. It’s not fair,’ she says, through the muzzle.

The woman’s mouth becomes a dark oval hole.

‘Go!’ shouts Angela, as the car careens down the cul-de-sac towards the carriageway. ‘Don’t come back!’

Angela stuffs the mask back in her pocket. She feels guilty but high all the same. It wasn’t so much that she wanted to scare off the lovers or punish them. She simply needed to reclaim the cul-de-sac.

As she retraces her steps around the turning circle, a cat leaps from Martin’s end wall, yowling on contact with the road. Angela phones Val from her mobile.

‘You were the woman in Cat People,’ she says. ‘I just remembered. Sorry if I woke you but …’

‘I’m still awake,’ says Val. ‘I’m never awake beyond nine. It’s the blue drink I think.’

‘You had a velour black catsuit,’ says Angela.

‘I had silk fucking whiskers out to here,’ says Val, after a pause. ‘My tail was even longer than yours.’

‘You should get to sleep now,’ says Angela.

‘We’ll speak tomorrow,’ says Val.

When Angela arrives home, Pete is waiting for her by the console table in the hallway, in the neck brace and noise-cancelling headphones.

‘Where were you? I looked everywhere,’ he says.

‘I have to do everything myself,’ she says. ‘You never listen.’

‘They’re streaming the Day of the Dead trilogy in HD,’ he says. ‘I’m recording it.’

Angela walks past her husband towards the conservatory, fishing out the remote control from the side of the La-Z-Boy, switching the tele off.