Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

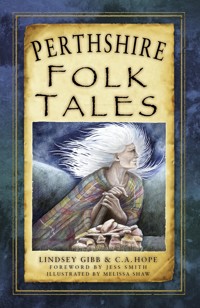

Storytellers Lindsey Gibb & C.A. Hope bring together stories from Perthshire, the heart of Scotland, with its bleak moors and majestic mountains, rushing rivers and great woodlands. In this treasure trove of tales you will meet witches and faeries, black dogs and dragons, the Cailleach and those mysterious painted people, the Picts – all as fantastical and powerful as the landscape they inhabit. Retold in an engaging style, and richly illustrated with unique line drawings, these humorous, clever and enchanting folk tales are sure to be enjoyed and shared time and again.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 254

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Text © Lindsey Gibb and C.A. Hope, 2018

Illustrations © Melissa Shaw, 2018

The rights of Lindsey Gibb and C.A. Hope to be identified as the Authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 8826 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press Printed in Great Britain

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

LINDSEY GIBB is a professional storyteller living in Highland Perthshire. She grew up surrounded by stories, and her love of nature and history is reflected in her storytelling. She performs all over Scotland as well as delivering workshops and enjoys collecting tales from her local area.

C.A. HOPE grew up in Scotland surrounded by books and history, where reading and writing were encouraged. She works in wildlife conservation but there is never a time when she is not absorbed in a writing project. Her enthusiasm for history drives her to bring the past alive by engaging and entertaining readers.

ABOUT THE ILLUSTRATOR

MELISSA SHAW is Scottish, living in Perthshire. She attended Stirling University, graduating with a BSc in Conservation Biology and Management (Hons). She has always enjoyed creating pieces of art, whether drawn or crafted from wire and beads. She is particularly inspired by wildlife, especially insects or imaginary magical creatures. Her enthusiasm for new experiences meant she was delighted to contribute to Perthshire Folk Tales.

CONTENTS

Foreword by Jess Smith

A Note from the Authors

Map of Perthshire

Starting in the South

Golden Cradle of the Picts

Away with the Faeries

St Serf and the Dragon

The Legend of Luncarty

Janet’s Dream

The Piper of Glendevon

The King o’ the Burds

The Wizard

The Packman

Bessie and Mary, Twa Bonnie Lassies

The Witch and the Bridle

Heading East

Messy Morag

The King and the Fool

The Harper’s Stone

Creepy Ghost Story

Mungo the Cobbler

The Green Lady of Newton Castle

The Finger Lock

A Stony Dilemma

The Wee Bird

The Challenge

The Giants of Glen Shee

Westward Bound

The Wee Speckled Stone

The Gabhar

A Bit of Land

The Kissing Ghost

The Cailleach of Glen Lyon

Go Boldly, Lady

The Man with Knots in his Hair

The Loch of the Woman

In the Black Woods

Lady of Lawers

The Minister and the Faeries

St Fillan’s Holy Pool

The Seer of Rannoch

The Laird’s Bet

Yellow-Haired William

Wee Iain MacAndrew

Moving North

The Whistler

Tam MacNeish

The Woman who Lived with the Deer

A Devilish Card Game

The Witch and the Shepherd

The Urisk of Moness Burn

The Wife of Beinn a’ Ghlò

Donald of the Cave

The Faeries of Knock Barrie

Sundancing

What Not to Say to a Broonie

Black Dog of Dalguise

The Wild Man of Dunkeld

In the Foothills of Schiehallion

Glossary

FOREWORD

Sitting between Scotland’s highland line and her central belt, Perthshire has long been revered for her ancient stories. Carefully yet generously shared from one generation to the next, the inhabitants of Perthshire have opened doors into a world of ancient stories by protecting and nourishing both the history and tale that wraps itself around the times. In the past Perthshire spoke a form of ancient Gaelic, so no surprise to hear the mix of Scots and Gaelic tales intertwined in this book.

Tales from Celtic, Pict and all peoples in between remain as fresh today as they did all those centuries ago.

Perthshire is the seedbed of ancient tales and this book, with all its magical and mysterious tales, is a wonderful collection of many of those loved and handed-down stories.

Plucked from heather moorlands, stormy seas, deep mist-covered lochs, hidden lochans, sparkling waterfalls, concealed caves, bracken-strewn braesides, little black houses, mighty castles and many unseen places from Scotland’s keeper of ancient tales, the authors have gathered a selection to please every lover of the ‘tale’.

The authors have spared no inch of Perthshire as they searched nook and cranny unearthing gems awaiting lovers of myths, legends and historical stories concealed within the following pages.

Beginning their journey for the reader’s delight they start in the south, opening the imagination with ‘Golden Cradle of the Picts’.

The authors then lead us onwards sharing tales, which leap like the giant River Tay salmon, heading east with gems such as ‘The King and the Fool’, then travelling westwards onto a platform of wonder with ‘The Cailleach of Glen Lyon’, to finish the journey moving north with other magical stories such as ‘The Witch and the Shepherd’.

If, during twilight hours, you wish nothing more than a few quiet minutes, draw the curtains, curl up with a comfy cushion and relish away the hours within the wonders of this book.

If the open spaces are to your liking then why not add this book to the flask and sandwiches as a worthy addition to the backpack. There are stories to suit any environment and atmosphere. Watch the children’s wide-eyed wonder at the hidden gems in the pages of this excellent book.

In times gone by, at the end of the day, a long-awaited highlight of children’s lives was always a story; tales of good witches and not so nice; tales of urisks and the wee broonie who did all the work no one would do during daylight; also faerie tales, giants and countless heroes and heroines, plus tales of tears and laughter and enchantment of ghostly goings-on.

Today we rely so much on electronic gadgets that we have forgotten that a simple telling of a story can open the mind of a child and raise them onto levels of creativity that helps in ways no man-made system can.

Perthshire Folk Tales can take readers, young and any age, to places they have seldom been, on flights of fancy and fantastic journeys where all things are possible!

I thoroughly enjoyed every story and can’t wait to hear how you enjoy these droplets of gold awaiting your delightful immersion.

Note: It is believed that the Picts (painted ones) built Perth (Bertha), the city that sits on the River Tay, Perthshire’s arterial lifeline for most of the source-beds to the fantastic tales in this book. Experts claim both Celt and Pict were amazing storytellers, so given the wealth of the ancient stories included here perhaps the authors may well hold a measure of both Pict and Celt in their veins.

To understand both the historical links and the old and ancient times of Scotland, the county of Perthshire holds all in the palm of her Pictish hands.

Jess Smith, 2018

A NOTE FROM THE AUTHORS

We are absolutely thrilled Jess Smith agreed to write the foreword for our book of Perthshire Folk Tales. Jess is an author, singer and award-winning traditional storyteller. She is one of the last of Scotland’s Perthshire Travellers, well known for performing and telling her stories all over Scotland and beyond. Through her writing and storytelling, Jess keeps the old ways of the people of Scotland alive. Her mine of knowledge has been gleaned from tireless research, her own Traveller’s background and a passion for sharing Scotland’s rich heritage. Sincere thanks to you, Jess.

The beautiful illustrations accompanying the stories are the work of the very talented Melissa Shaw. We are so lucky that, despite her hectic schedule, Melissa embraced this project and remained unfazed by some of our stranger requests! Her skill and enthusiasm has created delightful drawings to complement the individual nature of the tales.

In our search through the abundance of Perthshire tales and legends, we are indebted to generations of Travellers, storytellers, ministers of the church and all the folk who told and retold these stories over the passing years. There is one young lady in particular who provided us with a veritable treasure trove: Lady Evelyn Stewart Murray.

Lady Evelyn was the youngest daughter of John Murray, 7th Duke of Atholl, and his wife Louisa. We shall be forever grateful to Lady Evelyn who, in her early twenties, undertook the mammoth task of travelling around the Atholl Estates writing down the folk tales and songs of her father’s tenants. Originally recorded in Scottish Gaelic in 1891, they were translated by Sylvia Robertson and Tony Dilworth and published as Tales from Highland Perthshire in 2009.

The following tales are laid out roughly as if you are approaching Perthshire from the south, then heading east, across to the west and finally venturing into the north: Highland Perthshire. The general nature of the tales change as you move from the benign rolling hills and fertile land of the southern areas, up into the rugged, mountainous north. The borders of the county have been moved many times over the centuries and will, no doubt, move again, so as a rule of thumb we have included a story if it was set in Perthshire at the time it happened.

Whether tragic or funny, supernatural or magical, it has been a pleasure and privilege to retell these tales and keep the lives, beliefs and experiences of our ancestors resonating into the future.

LG – Thanks to my mum for sharing her love of stories and storytelling with me and to my fabulous friends for their support, particularly Cat, Dot, Shiona and Munro. The biggest thanks of all goes to Cherry, who made the book happen.

CAH – This was a very different writing venture for me! Many thanks to Lindsey for making this such an enjoyable collaboration.

MAP OF PERTHSHIRE

STARTING IN THE SOUTH

GOLDEN CRADLEOF THE PICTS

Over a thousand years ago the great country we now call Scotland was in the grip of power struggles between the Vikings, the Scots and the Picts. Stories handed down through generations provide a vivid picture of relentless violence. Bloody battles raged, driven by both intelligence and brawn, and the wily strategies to take control of the people and land became the stuff of legend.

One such tale has lasted the test of time and concerns the town of Abernethy in the middle years of the ninth century.

At dawn on a summer morning, King Drust of the Picts set out from his stronghold at the base of Castle Law with the last of his warriors. Years of fighting had reduced them to a motley force but they marched proudly behind their King, standards waving, their loved ones cheering and crying until they were out of sight.

King Drust knew his reign was coming to an end. He was heading north to Scone to face Kenneth Alpin (Cináed mac Ailpín), King of the Scots. There are two versions of the terrible events which occurred that day, and which one you believed depended on whether you were a Pict or a Scot.

Some say the Scots set a deadly trap for King Drust. The two enemies were meeting for an uneasy banquet at Scone where there was much revelry, music and dancing, with Kenneth’s serving girls keeping the goblets well-filled with liquor. While the Picts were in a jovial, numbed state, the Scots made their move. Pulling out pegs from under the long trestle seats, they dropped their enemies into prepared trenches filled with blades and sharpened spikes.

The other version tells us King Drust led the charge against the King of the Scots on the battlefield and was cut down and killed amid the bluster and courage of the fight.

Either way, King Drust was killed.

Fleet-footed runners rushed south over hills and through glens to carry the tragic news back to the Pict’s fort at Abernethy. Before leaving, King Drust had warned his wife and all the members of his household of the inevitable Scots’ victory, so the news was not unexpected. They recalled his passionate words, urging them to make the best of their lives under the Scots rather than be needlessly slaughtered before their time.

Nevertheless, on hearing confirmation of his death, the fort erupted into wailing, cursing, arguing chaos. It would not be long before Kenneth’s soldiers would be at the door to take their gold and quash any revival. The older folk believed they should stand firm: they were Picts until the day they died and would not submit to the Scots. Others felt it was futile and started to unbar the door, preparing to kneel before their victors and keep their heads on their shoulders.

Up in one of the attic rooms, King Drust’s faithful old nursemaid scoured the horizon for any sight of approaching Scots. She was disgusted by the feeble cries of defeat and had a far more important subject on her mind. While the queen wept and wrung her hands downstairs in the main hall, the old nurse moved rapidly to take action.

Ever since he was born, when she cared for him as an infant, King Drust had trusted her implicitly. In recent years, he had made her responsible for the two most valuable things in his life and she knew these two things would be the first to be taken by the King of the Scots: his baby son and the cradle in which he lay.

The golden cradle was an ancient royal heirloom. Wrought from solid gold, nobody knew where it came from nor who created such a wondrous work of art, only that every baby born to a Pictish king was laid in this cradle. Oh, how much the King of the Scots would want to own this potent symbol of the Picts!

She knew what she must do. She knew she couldn’t pick up the cradle. It was very, very, heavy and had remained as if stuck to the floor for many a year. There was no time to lose but she could barely even drag it across the floorboards so she ran down to the kitchens. Within minutes she was back in the attic with the baby’s devoted young nursery maid and a brawny but brainless young man. They clustered around the golden cradle and managed to haul it down the back stairs, baby and all. Leaving the fort by a secret door, they scurried towards the cover of trees overhanging a burn and headed up Castle Law, staggering and slipping beneath their burden. Behind them came the terrifying sound of the approaching spear-wielding Scots, King Kenneth riding at the front.

The nursemaid may have been in advancing years but her heart and lungs were strong. All the way up Castle Law she muttered under her breath. Bullying and encouraging the servants to keep going, she vowed to stop the cradle and the infant king from falling into the Scots’ hands.

When they reached a shoulder on the hill they paused for breath, looking down at the besieged fort. Below them, one of the Scots’ soldiers noticed the sunshine glinting off the radiant gold and a cry went up! Kenneth’s sharp eye recognised the cradle and he set off in pursuit with a group of soldiers.

By the time they came over the brow of the hill, the nursemaid had moved on towards a loch. It was here, at the lochside, that they found her: alone.

She was sitting waiting for them on a rock above the water. The ribbons on her cap neatly tied, her skirts arranged over her knees, bare feet dangling in mid-air and her arms locked around the golden cradle. It seemed to the watching Scots that she took a breath, or perhaps she was speaking, for her mouth gaped open and her eyes focused on them as she pitched forward and plunged into the water.

King Kenneth shouted urgently to his men to dive in and retrieve the precious golden cradle, adding as an afterthought for them to save the royal baby. Shields and armour were unstrapped, heavy boots hastily unlaced with shaking, exhausted fingers but in these few short moments the hot summer day grew dark. Black clouds appeared, swirling overhead to send raindrops pelting down, whipping the loch’s surface into a white froth.

Up from the water rose a colossal wave, its crest falling in an endless waterfall to rise again and again, twisting into the shape of a bony, writhing old crone. Her watery cloak billowed out from around her shoulders and the raging gale swept back her straggling white hair to show jagged features and oversized, staring eyes. Deep, resonating sounds reverberated through the ground like thunder, but it wasn’t thunder. Words spilled from the towering supernatural creature in a voice so low and so loud and so shocking they were hard to decipher; even King Kenneth dropped to his knees.

Her warning given, the old hag disappeared back into the depths, leaving the rain hammering down through an eerie silence. Terrified and defeated in their quest for the golden cradle, King Kenneth and his men made their way off the hill, not daring to look back.

And what of the heir to the Pict throne, King Drust’s baby son? Did that fiercely loyal nursemaid really drown her little charge, as she wished King Kenneth to believe? Or, did she sacrifice herself to divert attention from the little maid slipping away over the hills with a baby in her arms? If so, the bloodline of our ancient Pictish kings is still alive: somewhere.

Tantalisingly, a long time ago, golden keys were found in a local stream:

On the Dryburn Well, beneath a stane

You’ll find the key o’ Cairnavain

That will mak a’ Scotland rich, ane by ane.

These keys are said to release the hoard of Pictish gold which was hastily and secretly buried between Castle Law and Cairnsvain on that fateful day.

The words spoken to King Kenneth and his soldiers by the old hag from the water gave clues of how to claim the cradle from the loch. The exact words have been lost from memory but are loosely recalled as meaning a man (or woman) should go alone to the lochan at dead of night. They must go round the loch nine times, encircling it with green lines and only then will they find the golden cradle.

For anyone thinking of trying to retrieve the golden cradle, a caution should be given. Although many have attempted this feat, none have succeeded and, more worryingly, many have either lost their wits or never been seen again.

AWAY WITH THE FAERIES

It was nearing the Winter Solstice and two young men went off to buy some whisky from a neighbour’s secret still in the next glen. They made their purchase and passed a few words with their friend then set off home, a barrel slung between them. It was a frosty afternoon and with only an hour or so of daylight left they strode along, their breath foaming on the air.

On passing a hillock, one stopped, catching hold of his friend’s arm and urging him to pause and listen. A beautiful melody came tinkling from over the rise in the heather. They laid down the whisky and crept cautiously up to the crest of the hill, the music growing louder with every step.

A crowd of faerie folk were dancing to the wondrous music, whirling each other around and beckoning to the men to join them. The harmonious tune made their hearts sing and their toes begin to tap but the older of the two was wary.

‘Come away, we must be gettin’ hame.’

His friend did not move, delighting in the magical sight of fantastically vibrant colour and merriment beneath the darkening sky. Wee folk were flitting here and there, lighting scores of lanterns and candles, jigging and laughing along with the sweet notes from pipes and fiddles.

Again the other man tried to persuade his friend to leave but without success, so he went home alone, bearing the barrel on his back. The villagers were very suspicious. Where was his friend? What had happened? They searched high and low and did not believe the story of the faerie gathering. Tempers ran high and the man was accused of killing his friend and hiding his body.

‘I tell you the truth!’ the man pleaded. ‘I left him watching the faeries and he was alive and well. Allow me one year and I shall prove I am no murderer.’

Exactly a year since he last saw his friend, the accused man returned to the hillock. There, in the same place as he had left him, stood his friend!

‘Come awa’ hame now,’ he told him.

The friend waved a hand impatiently, ‘Och, man, let me watch. Just a minute or two more.’

‘Ye’ve bin here a full year, come away hame noo!’ He grasped his friend firmly by the jacket and after a struggle, he dragged him home. They argued all the way back along the track, with the rescued man flatly refusing to believe he had spent more than a few minutes watching the faeries. It was only when he reached his village and everyone ran out to see him, and his mother and wife both fell on him with tears of relief, that he began to doubt his own mind.

Then he saw the calf he left in the barn, now a stout beast, but on opening his front door he came fully to his senses. His son, a babe in arms when he left, came running across the parlour with hands outstretched to be picked up. He hugged the child close and declared that yes, he must have been away with the faeries for a full year.

ST SERFAND THE DRAGON

On the southern bank of the River Earn, a few miles south of Perth, lies the pretty village of Dunning. Nestled below the Ochil Hills, its perfect setting has been chosen as a safe, fertile dwelling place for at least the last five thousand years.

There must be many tales from Dunning from early Iron Age settlers and Roman camps but this story has been kept alive from when Scotland was Pictland.

Fifteen hundred years ago, the daily lives of the Dunning villagers revolved around raising families, rearing livestock and making sure there was plenty food for everyone.

One day, this happy existence was brought to a standstill when a dragon came marauding off the hills. It stamped its way towards Dunning’s cluster of wooden houses, snatching up and eating small animals and whole fruit trees; dribbling and chomping as it went.

Mothers grabbed their children and fled indoors, barring the windows and doors. Men pushed their frightened livestock into byres and guarded the doors, armed with sticks and pikes, terrified.

The beast swaggered across carefully tended vegetable patches, its tail swiping from side to side, knocking down haystacks and trampling woodpiles as if they were twigs. After several awful, breath-holding minutes, it stomped on across the floodplains and took a drink from the Earn. Then it returned to the hills and was lost from sight.

Of course, the appearance of a dragon caused a terrible uproar! Nobody felt safe and, worse, few people at the markets in Perth or Auchterarder would even believe it happened.

Unfortunately for the people of Dunning, the dragon kept returning.

There was a very holy man travelling through Strathearn, St Serf. He had held the office of Pope in Rome for seven years before finding it too restrictive and setting out on his own as a missionary. His footsteps took him up through Gaul (what we now call Europe) then across the Channel and northwards until he reached Pictland.

By this time, he had already founded a religious community on an island in Loch Lomond, now called St Serf’s Inch. His restless, evangelical nature kept him moving, earnest in his duty of spreading the word of God and stamping out pagan beliefs. For all that, he was unanimously found to be a kindly, benevolent man by everyone who met him.

When St Serf drew close to Dunning, the villagers ran out to greet him. They invited him in to one of the elder’s houses and told him of the ‘dragon, great and loathsome, whose look no mortal could endure’. He listened, solemnly, while they ogled at this foreign holy man. With his aquiline features, dark eyes and black beard he was a fine sight, being the son of an Arabian Princess and the King of Canaan.

Suddenly a cry went up: ‘Dragon!’

Everyone rushed about shouting, shooing chickens, banging doors shut, slamming bolts home and barricading themselves indoors.

St Serf went out to meet the creature.

The dragon’s huge head swung round, its glistening, bloodshot eyeballs pointing directly at the approaching figure, straight-backed and calm with just his faith and a staff in his right hand to defend himself.

Peeping through the gaps in their shutters, the Dunning folk watched in fascination as St Serf kept walking directly towards the dragon. It reared up and thrashed its tail, snaking out its long neck to bring its scaly head down low towards the man. At every breath and roar, the grass flattened, leaves ripped from the trees and St Serf’s robes whipped back against his body, but he didn’t falter.

Raising his staff high, he brought it down on the dragon’s head with a mighty thwack, right between the eyes! The beast collapsed to the ground.

Tentatively at first, then in crowds, people emerged from their hiding places and ran to give thanks to the holy man.

From then on, the spot where St Serf slew the dragon has been known as Dragon’s Den. St Serf stayed for some time and a church bearing his name was built there in the twelfth century, which can still be seen today by all who wish to visit.

THE LEGEND OF LUNCARTY

Over one thousand years ago, near the little village of Luncarty, a ferocious battle took place between the Scots and invading Norsemen. The skirmishes and conflict between these two nations ran for over two hundred years but it is claimed the clash at Luncarty in ad 980 is particularly memorable. Not only did it dramatically change the life of a poor farmer but it gave Scotland its national flower.

In the closing decades of the tenth century, Kenneth II reigned over the Scots. He was at Stirling Castle when a rider brought the dreadful news that Danes had landed near Montrose. Survivors fleeing the invasion told of men, women and children being killed and dwellings torched as the Norsemen advanced through the countryside towards Scone; the royal centre of Scotland.

Alarmed, King Kenneth declared a promise of payment in land or money to anyone bringing him the head of a Dane. Then, although nearing his fiftieth year, he gathered his army and led them north to do battle.

Dusk was falling on the second day of the march when the king reached Luncarty, a hamlet on the west bank of the Tay, just upstream of Perth. They were greeted with the news that the Danes were settling close by for the night, so the Scots also set up camp and planned to attack at first light.

However, King Kenneth was not the only one being given information on their enemy.

It was still dark when the Norsemen rallied and began to creep across the open meadows towards the King’s men. The first the Scots knew of approaching danger was a cry of agony from a Norseman pierced by a thistle. Alerted by the sound, the Scots were sent scrambling to their feet and seizing their swords just in time to face the warrior figures charging towards them through the grey dawn.

Caught unawares, Kenneth hastily ordered his men to the east and west, taking command of the central force himself. It was a violent, bloody battle; the screams of pain masked by the crash of blades and roaring bluster of foe on foe bellowing their vicious intent. Men fell in heaps from both sides, the dead and dying lying entwined on the crushed woodland floor and pastures.

The overwhelmed Scots began falling back and it soon became evident to the king that the Danes were winning.

A farmer by the name of Hay was tending a patch of land nearby and stopped to watch. With rising horror he saw his countrymen retreating. Shouting to his two strong sons to unhitch the oxen, they brandished parts of the yoke and plough as weapons and dashed towards the affray, hollering and bawling.

All three men were tall and rugged, with muscular bodies built from a lifetime of labouring on the land. With their features contorted with murderous intent, hair and beards straggling wildly as they ran, they appeared to both friend and foe to be the forerunners of fresh reinforcements.

‘Help is on its way!’ they yelled, tearing down the narrow track between two hills where the king’s soldiers were being driven backwards. ‘You must not give up! Fight on! Help is here!’

Seeing these new, strong allies made it easy to decide between dying with honour on the battlefield or running away to be slaughtered by the Danes snapping at their heels. Kenneth’s troops rallied to Hay’s cries. As one mass, the Scots surged forward again, slicing and hacking with renewed valour.

The tide was turned. The exhausted Danes believed they were facing a fresh, fortified army and lost heart, and soon the Scots were victorious.

King Kenneth realised how close he had come to losing this vital battle and acknowledged the heroes of the hour. Had it not been for the spiky Scottish thistle his soldiers would have been massacred in their sleep. Legend has it that this is how the thistle became Scotland’s national flower.

The country was also deeply indebted to the brave farmer and the King summoned Hay to Scone to bestow his reward. He dispatched the royal falconer to climb nearby Kinnoull Hill and release a peregrine. Wherever the bird came to light would mark the extent of the land he would give to the Hays. The peregrine flew east for six miles over the hills and glens of the Carse of Gowrie and this land, bordered by the Tay, became Errol. The King also raised the Hay family to nobility by giving them a crest, depicting a falcon and three shields: the three men being the shields of Scotland.