Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

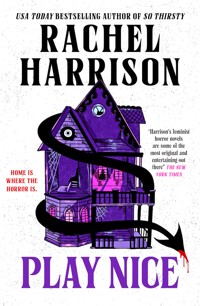

A NEW YORK TIMES and USA TODAY bestseller. A woman must confront the demons of her past when she attempts to fix up her childhood home in this devilishly clever take on the haunted house novel from the author of Black Sheep and So Thirsty.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 433

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

After

Acknowledgments

About the Author

“Rachel Harrison is in a league of her own—maybe a genre of her own. Play Nice is the sexiest, scariest, most fun haunted house novel I’ve ever read, a Barbie Dreamhouse oozing blood, one of those perfect blends of horror, heart, and winking wit only she can pull off. This book is so gripping it performed its own possession; I physically couldn’t put it down. Harrison is my horror queen, and this book is her best yet.”

ASHLEY WINSTEAD, USA Today bestselling author of Midnight is the Darkest Hour

“I raced through Rachel Harrison’s Play Nice, drawn in by the relatable protagonist and the irresistible blend of horror, mystery and family drama. Play Nice is a great fit for anyone who enjoyed The Good House or Grady Hendrix’s How to Sell a Haunted House, taking the reader on a spooky journey through the haunted spaces from the past that plague us all.”

TANANARIVE DUE, Bram Stoker Award® winning author of The Reformatory

“Play Nice is as fun as a journey into darkness and family trauma can get. Rachel Harrison crafts a uniquely spirited haunting that’s both ruthlessly frightening and overflowing with heart.”

CHUCK TINGLE, USA Today bestselling author of Lucky Day and Bury Your Gays

“Play Nice packs a prickly punch by cleverly nesting its possession story within another kind of familial and familiar possession. While the demon at the center of it all terrorizes the women in Clio’s family when they are most vulnerable, the book is scary because there’s more than one kind of demon.”

PAUL TREMBLAY, New York Times bestselling author of Horror Movie and The Cabin at the End of the World

“Rachel Harrison once again gives us our best friends, our best enemies, our best crushes, and our worst nightmares. This time sexier, scarier, grittier than ever before.”

CJ LEEDE, USA Today bestselling author of American Rapture

“To call Play Nice Rachel Harrison’s scariest book yet is to perhaps risk downplaying how it’s also as deft and gripping a guessing game about literal and metaphorical demons as A Head Full of Ghosts or The Haunting of Hill House. Yes, this book is just that good. But it’s also scary as hell.”

NAT CASSIDY, author of Mary and When the Wolf Comes Home

“Real estate is hell, and that’s before you add in family secrets, inherited trauma, the lie of objective truth, and also a literal demon. Play Nice is a funny, deft, and very scary novel about an influencer, a possessed house, and the inescapable horror of realizing you can never truly know another person, even (or especially) when they’re family. No horror writer currently working has a better understanding of the inner lives of millennial women – Rachel Harrison is in a class of her own, and Play Nice is her best book yet.”

EMILY C. HUGHES, author of Horror for Weenies: Everything You Need to Know About the Films You’re Too Scared to Watch

“Play Nice is Harrison at her best. Creepy, paranoid, and full of heart. A nuanced, humanistic take on the supernatural. How our lives and relationships are haunted by our past… sometimes literally. A home possession thriller that sits on the same block as Amityville, but has significantly higher resell value.”

ADAM CESARE, author of Clown in a Cornfield and Influencer

“Rachel Harrison isn’t playing around. Play Nice is her scariest book so far, by far, so don’t say you weren’t warned. Reading Rachel is akin to an incantation, summoning a master craftsman of horror, then ending up possessed by her downright demonic ability to hurt and haunt you all at once. No exorcism will expel this novel from your consciousness.”

CLAY MCLEOD CHAPMAN, author of Wake Up and Open Your Eyes

“Play Nice is an exorcism of a haunted heart—a singular, obsessive, and deeply palpable examination of the wounds we mend from the trauma, the excruciating cruelty we inherit from our loved ones. Harrison deftly balances between moments of quiet, poignant reflection and unhinged brutality in this eerie shocker about possession, family, and secrets. An impressive and equally unforgettable work, Rachel Harrison is the new Queen of Horror.”

ERIC LAROCCA, author of Things Have Gotten Worse Since We Last Spoke

“Rachel Harrison is on a bloody hot streak. Even if you’re a fan of her previous works, you are not prepared for what Play Nice has in store for you. Protagonist Clio might be her nastiest, messiest creation yet; Harrison is the master of writing characters you want to be best friends with but also hope you never meet.”

LIZ KERIN, author of the Night’s Edge duology

Also by Rachel Harrisonand available from Titan Books

Cackle

Such Sharp Teeth

Bad Dolls

Black Sheep

So Thirsty

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Play Nice

Print edition ISBN: 9781835414774

E-book edition ISBN: 9781835414781

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: September 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Rachel Harrison 2025

Published by arrangement with Berkley, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner for the purpose of training artificial intelligence technologies or systems. This work is reserved from text and data mining (Article 4(3) Directive (EU) 2019/790).

Rachel Harrison asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

EU RP (for authorities only)eucomply OÜ, Pärnu mnt. 139b-14, 11317 Tallinn, [email protected], +3375690241

Designed and typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro by Rich Mason.

For the crazy girls.This one is for us.

Yes.

Yes.

I accept you, demon.

I will not cover your mouth.

—Anne Sexton, “Demon”

It needs, it seeks affection

Hungry, it fiends

Look at me, look at me, you lookin’?

—Doja Cat, “Attention”

Behind every crazy woman is a man sitting very quietly, saying,“What? I’m not doing anything.”

—Jade Sharma, Problems

PLAY NICE

1

We’re coming up on midnight. The room is loud, everyone champagne drunk, ignorant of volume, and, wow, the air in here is intense, all hot breath and designer perfume. Everyone wants to smell good because this is the hour it happens, when it’s determined who goes home alone, and judging by the pungency, a lot of people in here don’t want to end up in an empty bed tonight. They want to attract. They want to be chosen. So they sneak off to the bathroom to fix their hair, stare at their smudged reflections, primp, powder, perfume—spritzing excessively, with reckless abandon. I inhale.

It’s hope, is what it is. It’s sweet but also pretty desperate. Pretty boring.

I turn to the guy next to me. He’s deliberately under-dressed in a white T-shirt and jeans. He’s drinking a beer. I thought this party was too chic for beer.

“Where did you get that?” I ask him.

“The bar,” he says in a tone I don’t care for. I stick my tongue out at him, and he cracks a smile.

“Clio Louise Barnes,” I say, holding out a hand.

He stares at my hand for a moment before shaking it. “Ethan.”

“What do you do, Ethan?”

“Really?”

“What?”

“Small talk?”

“We can exchange childhood traumas if you like,” I say, helping myself to a sip of his beer. He allows it to happen, and I decide I’m into him. He reeks of cologne, so I know I can leave with him tonight if I want to.

“We’ve already met. Several times, at brand parties just like this one,” he says. “I was waiting for you to remember.”

I do remember. But the easiest way to tell who a man really is, is to injure his ego and see how he reacts.

“I’m bad with names. And faces,” I say. “And I meet a lot of people. I’m sorry. Please don’t take it personally.”

He rubs his jaw, considering. “You really don’t remember?”

“Do you forgive me?” I give him puppy eyes, bat my lashes.

He sighs, then lifts his chin and points to a thin scar, about three inches long. “Car accident when I was five. Blood everywhere. Mom was driving. She was in a coma for a week.”

“Is she okay?”

“Yeah. She’s got scars, too. But that’s it.”

I sip my champagne. I like it better than the beer. I wish I had simpler tastes, but I don’t. “Lucky to live with scars.”

“Better to live without,” he says. “What about you, Clio Louise Barnes? Childhood trauma?”

I debate making something up, but I’m intoxicated. From the alcohol, yeah, but also from the balmy heat, the formidable amalgam of smells, the city outside alive with that magnificent Saturday night energy. So I tell him something true. “I grew up in a haunted house.”

“Bullshit.”

“Sorry, not haunted. Possessed,” I say, bringing the coupe to my lips and taking a delicate sip, letting the effervescence dance across my tongue. I’ll need a refill soon.

“Possessed by what?”

I shrug. “That’s all I’ve got for you. If you get me another drink, maybe I’ll tell you more.”

“We’ve been down this road before,” he says. “You flirt with me, so I buy you a drink. Then you disappear at midnight like some kind of Lower East Side Cinderella.”

“Oh, was I flirting?” I say with a grin. “My bad.”

He doesn’t react.

“The drinks here are free.”

“And?” he asks.

“So, what do you have to lose?”

He downs the rest of his beer. “All right. Another champagne?”

“Yes, please.”

He takes my near-empty coupe. “You better be here when I get back.”

I cross my heart.

* * *

We step onto the sidewalk, the click of my heels echoing, harmonizing with the rest of the city sounds—traffic and drunken gossip and subway squeals and club bass. Ethan is warm, which is convenient, because it’s early April, and the night air carries a tenacious chill, winter dragging its feet.

“What time is it?” I ask him. He’s the CEO of a cool, successful watch company. He used to date my friend Veronica’s friend Laurie before the cursed launch of her lipstick line. She named the shades stupid things like “Get Him Back” and “Divorcée” and the supremely controversial “Jailbait.” Then customers found hair and a mysterious gritty substance in the product, and just like that, her career was over. She moved to Florida, and now she does makeup for Disney weddings.

I’m not sure if Ethan broke up with her before or after the fiasco. Not sure it matters.

“Clio?”

“Sorry,” I say. “What time?”

“One twelve,” he huffs, annoyed at having to repeat himself.

“Amazing,” I say, spinning. “I didn’t turn into a pumpkin.”

“Do you want to get an Uber?” he asks. “We can’t walk to Brooklyn.”

He thinks he’s coming home with me. I suppose it’s a fair assumption since we left the party together, but I still haven’t made up my mind.

I like that he’s warm. I like that he’s good-looking.

I don’t like that he’s got on so much cologne. I don’t like how he thinks he’s so successful that he’s above a dress code. And I don’t like that I’ll forever associate him with poor Lipstick Laurie. Maybe it isn’t his cologne that I’m smelling but the persistent stink of someone else’s failure.

“Your phone’s ringing,” he says. “It’s been ringing.”

“Mm.” I hear it—my phone—I’m just keen to ignore it. I watch a group of girls in short dresses stumble out of Scorpio, a nightmare of a club no one goes to if they know better.

“Are you going to answer it?” he asks.

“Nah,” I say, swinging my gift bag from the party. “Nobody calling this late has anything good to say.”

“What if it’s important?” he asks.

“Relax, Daddy.”

“I don’t get you,” he says, shaking his head. He’s not mad, just disappointed.

“All right, all right,” I say, unclasping my clutch to get to my phone. My hand shimmers, covered in glitter from the party, which is to be expected since the theme was “All That Glitters.” A jewelry-line launch, Veronica’s partnership with Shine Inc. Gold charms. Cute but nothing special. I take out my phone to discover I have seventeen missed calls, all from my sisters. “Uh-oh.”

“What is it?” Ethan asks. “Everything okay?”

“I’m about to find out,” I say as my phone rings again. It’s Leda. I hit ignore and call Daphne instead. Whatever the reason they’re calling, I’d rather hear it from Daphne.

She picks up immediately. “Hey, baby Cli.”

It’s bad news, I can tell by her voice. Daphne’s like a shape-shifter, a side effect of being the middle child. She adapts to the circumstances, fits into whatever space she’s allotted; the queen of appeasing.

“What’s up, Daffy?” I ask, walking away from Ethan. I turn the corner, lean against a boarded-up, graffitied storefront.

“Did you talk to Leda?” she asks.

“No. Why?”

She takes a breath. “Where are you right now?”

“Out,” I say. “On the town.”

“Are you with someone?”

“Considering,” I say. “What’s going on? Is it Dad?”

“No,” she says. “No. Dad’s fine. Amy’s fine. Leda’s fine.”

“Don’t tell me it’s Tommy,” I say, picking at my gel manicure like you’re not supposed to.

“No, it’s not Tommy,” she says. “Thank God.”

“Thank God,” I repeat, crossing myself. Tommy is Leda’s pushover husband, who wears sweater vests in earnest. He’s too pure for this world and we love him.

“It’s Alexandra,” she says.

She doesn’t call our mother “Mom” because she hasn’t been that to us since we were kids. It’s cruel, I think, but it’s Daphne’s prerogative. Leda’s, too.

“Is she okay?” I ask.

“She’s … she had a massive heart attack. She called nine-one-one, but … she was gone before the paramedics arrived.”

“Oh.” I bring my glittery hand to my face, press into my cheek. “Gone as in …”

“I’m sorry, Cli,” she says. “Hold on. Leda’s texting me asking if she can talk to you. Can you call her?”

“Is she upset?” I ask.

“I think she’s worried about you.”

“Why?”

“Come on,” she says.

“Are you upset?”

“I’m processing,” she says. “I’m actually driving right now. I’m on my way to Dad’s. I think you should plan on making the trip tomorrow.”

“All right,” I say. My phone beeps. Leda’s on the other line because of course she is. “I’ll see you tomorrow, then?”

“Yep,” she says. “Love you, Cli.”

“Love you.” I switch over to Leda. “Hey. Daphne just told me.”

“We all had our own thoughts and feelings about Alexandra. But I know just because she wasn’t an active presence in our lives doesn’t necessarily make it easier to know she’s no longer with us,” Leda says. She for sure has been rehearsing this line since the moment she found out. Maybe even before then.

“Thanks, Leeds.”

“I wanted to be the one to tell you,” she says, stating the obvious. “I wanted you to hear it from me.”

“Daphne did a fine job,” I say. I notice a shadow creeping into my peripheral vision. It’s Ethan, standing at an awkward distance, watching me, a concerned look on his face.

“She was our biological mother,” Leda says through what sounds like a clenched jaw. Someday Leda will discover Xanax, and her quality of life will improve drastically. Until then, she needs to wear a night guard so she doesn’t grind her teeth to powder.

“Are you going to Dad’s?” I ask.

“Yes, I’m packing now.”

“’Kay,” I say. “I’ll catch a train in the morning.”

“If Aunt Helen calls, ignore it. I will handle,” she says.

“All right,” I say, aware that Ethan’s hovering ever closer. “I’m about to get a car back to my apartment. I’ll call you in a bit, yeah?”

“Text me when you get home,” she says.

“Will do. Love you with a cherry on top.”

“I love you, too,” she says.

I hang up and immediately open the Uber app, request a car.

“What service! Mitt is only two minutes away,” I tell Ethan. “Silver Toyota Corolla. Plate ends in X3.”

“Uh, is everything okay?” he asks me.

I drop my phone back into my clutch and pinch it shut. “My mom died.”

Seconds pass. A siren sounds somewhere in the distance. Someone else’s misfortune temporarily louder than mine.

“Wait, for real?” he asks.

I nod. “For real.”

“Holy shit. I’m so sorry.”

Mitt pulls up in his Toyota. I open the door, look back at Ethan, who stands stiff on the sidewalk, his eyes watery and wide, as if he were the one who’d just gotten the gloomy news.

“You want to come home with me or not?” I ask before sliding into the back seat.

He climbs in beside me, undeterred by my tragedy. Or perhaps motivated by it. If he wants to be my knight in shining armor, so be it. I snuggle into him, steal his warmth.

That’s all he is to me, body heat.

If there is an afterlife, if any of the wild things my mother believed are true, she’s somewhere watching me, proud.

I’ d rather you girls open your legs before you ever open your hearts, she said once, half a bottle deep. I was too young to understand then. So many things.

“Actually,” I tell Ethan. “I changed my mind. Get out.”

2

Rain taps at my window, a polite alarm. My eyes are slow to open, yesterday’s mascara gluing my lashes together. I got back to my apartment and fell into bed without undressing, brushing my teeth, or performing any of the many steps of my p.m. skincare routine.

“I have forsaken my serums,” I groan to no one.

There’s makeup smeared across my pillow, glitter all over my sheets. I roll onto my back and hear a soft crunch, reach underneath me to find my gift bag from last night’s party. I finger the heart-shaped tag with my name on it, then dump out the bag’s contents. Metallic tissue paper, clumps of glitter that will linger for eternity, and, finally, a small gold jewelry box with Veronica X Shine Inc. written in loopy script across the top. Inside the box is a pink velvet pouch, and inside that is a charm. A white gold snake with tiny diamond eyes.

I hook a nail through the jump ring and hold up the charm. There are a few ways I could take this. Veronica chose this charm for me because it’s the edgiest and most expensive in her collection and suits my style better than a heart or key or flower or whatever. Or I could be offended that she would gift me the snake, read too far into it. Thinking back, I don’t think I’ve ever done anything to her that would earn me the title of snake, but who knows.

My feet find the floor and I shuffle over to my dresser, to my jewelry tree, pick out a suitable chain, slide the charm on, and clasp it around my neck. I lift my eyes to the mirror, to my reflection, to study how the charm looks resting against my skin, but instead I see my mother, the traces of her face in my own, and I remember she’s gone. She’s dead, and I’m supposed to go to Dad’s today. Which means I need to take New Jersey Transit. As if the one tragedy wasn’t enough.

I find my phone still in my clutch, battery at ten percent. I plug it in and call Dad on speaker.

He answers right away. “Hey, sweetie. How you holding up?”

“Oh, fine, fine,” I say, yawning. “Are Daffy and Leda there yet?”

“They’re here. Amy’s making them pancakes,” he says.

“Dang. I love Amy’s pancakes.” My stepmom’s lone success in the kitchen.

“What time do you think you’ll be here?”

“Not sure yet,” I say, staring at my unmade bed, at the mountain of unwashed clothes in the hall. A wicked idea pops into my head. “I have to do laundry. I have to pack. How long am I coming for? Will there be a funeral?” I force my voice to break. “I’m sorry, Dad. I just, I wasn’t ready for this.”

“I know, Cli,” he says. “Why don’t I come pick you up?”

Too easy. “Really? Are you sure?”

“I don’t want you taking the train if you’re this upset. Let me go tell Amy and I’ll be on my way.”

My father. Steady and reliable, the captain of the ship, the benevolent king of our lives, his love as sure and powerful as gravity.

“Thank you, Dad. I love you.”

“Love you, too.”

I’d feel bad, but it’s not so far. An hour and a half, two with traffic. And, yeah, I may be a twenty-five-year-old woman calling her daddy to come pick her up, but the train is such a nightmare. I’d do worse things to avoid it.

I leave my phone plugged in, shove the laundry pile into the washing machine, and take a quick, cold shower. Towel off, then brush my teeth. Start my morning skincare routine. Consider what to wear.

Dad didn’t answer my question about a funeral, but I’m assuming there will be some kind of service. I own so many black dresses, yet none of them seem appropriate for mourning my mother. Which maybe is appropriate since I don’t know how to mourn her.

Would she even want to be mourned? She didn’t believe in death.

Once my makeup is done, I climb back into bed, unplug my phone, clip on my selfie light, and take a photo of myself in my bra and my necklace, my shiny new charm on display. It’s good enough to post to the grid. I tag Veronica, tag Shine Inc. Caption it with a snake emoji, a diamond emoji, some stars.

I stare at the picture. It’s obvious to me that my smile is fake. But it won’t be obvious to anyone else.

Another lesson from my mother, one she taught by unfortunate example. By showing us what not to do. By showing us how important it is to be in complete control of your emotions. It’s too dangerous the other way around.

* * *

Several hours later Dad is cleaning out my fridge and I’m still packing.

“It’s all takeout in here, Cli,” he says scoldingly.

“What can I say, cooking isn’t a priority for me. And before you lecture, remember feminism.”

“I know, I know,” he says. “You sound like Daphne.”

Daphne thinks she’s the most progressive in the family, but she got awfully judgmental when I told her I was considering starting an OnlyFans.

“All right. I’m going to take out this trash, and then we should be getting on the road,” he says. “I’m sure your sisters are anxious to see you.”

“I’m sure,” I repeat. We all love each other, but Daphne and Leda don’t always get along. I’m the family’s social lubricant, the special sauce.

I kneel before my open suitcase, contemplating its contents. Working in fashion has ruined my ability to be spontaneous, to be nimble even under these circumstances. What I wear matters, how I’m perceived matters. Sometimes I think it’s all that matters. Sometimes I know it is.

Dad comes back and waits impatiently as I finish packing, as I check and double-check that I have everything I could possibly anticipate needing or wanting. He carries my suitcase out to the car, griping about its heft as I lock up. When I get to the car, I throw my duffle in the trunk and slide into the passenger seat, putting my purse between my feet and shifting the seat back. There’s an unopened bottle of water in the cup holder, and I help myself, assuming it’s for me.

“Probably warm now,” Dad says. “It was cold when I got here.”

The plastic is wet with condensation, the label soggy. “That’s okay. Thank you for bringing it. And for driving me. And for waiting. And carrying my suitcase.”

He massages his shoulder before starting the car—perhaps an attempt to guilt me. He’s a six-foot-four Viking, and his hair has been salt-and-pepper for as long as I can remember, so it’s easy to forget that he’s creeping toward his mid-sixties, that he’s not indestructible. “What do you do when you go on all your trips? If this is what you bring for a few days.”

“Maybe a few days. I don’t have enough information,” I say, adjusting the vents so the heat isn’t blowing directly into my face. There’s still glitter on my hands. There will always be glitter on my hands. Glitter is permanent.

“I don’t either,” he says. “Helen didn’t call me. She called Leda.”

Not surprising. Aunt Helen, Mom’s older and only sibling, hates my father. Hates. Amy is a close second on her hit list. To say my parents did not have an amicable divorce would be like saying the Challenger did not have a pleasant flight.

“They have lunch sometimes,” he says, turning onto Flatbush Avenue. “Helen and Leda.”

“Are you asking me or telling me?”

He doesn’t respond, so I don’t respond. I know Leda has met with Helen, they both live in Boston, and Helen has been trying to get back in touch with us for years, and while Leda, a chronic overachiever with an iron will, could probably stop the earth on its axis if she put her mind to it, Tommy is a soft kitten who grew up in a normal family. He’s her well-adjusted Achilles’ heel and never approved of her steadfast disavowal of our mother. And while he couldn’t get her to budge on the issue of Alexandra, he could talk her into a lunch with Helen, which turned into several lunches, because Leda and Helen are cut from the same glorious rigid bitch cloth.

I know all of this, but I don’t know if our father does. It could be a trap, so I don’t confirm or deny.

“Can I put on some music?” I ask, already reaching for his phone.

“Sure, Cli,” he says. “Not too loud.”

I put on some Quiet Riot because Mr. James Arthur Barnes can’t resist some glam metal. Their cover of Slade’s “Cum on Feel the Noize.”

“Hell yeah,” he says, head bobbing. “Turn this up.”

“Sir, yes, sir.”

I continue to DJ for the rest of the car ride. We get stuck in traffic, so it takes longer than it should to make it to New Jersey, to my father’s house. Leda’s Mercedes is parked on the street, perfectly parallel to the curb. Daphne’s Subaru is parked haphazardly in the driveway—the beat-up hatchback she’s had since high school. She can afford a new one, but since Leda and I are materialistic, she decided not to be. Dad is careful as he pulls around her car into the garage, which is unnecessary. What’s another dent?

A simultaneous feeling of relief and unease rushes through me. It happens every time I step foot in this garage, in this house. Considering it’s the childhood home of mine that wasn’t haunted or cursed or whatever, I shouldn’t feel so haunted coming here. The feeling is fleeting, it never lasts, but it always happens. A swell of memories, the ghosts of past me, the precocious kid who was glad to be out of Mom’s house, where the atmosphere was tense, and there were no snacks, and everything stank of cigarettes and Chardonnay. But then also the guilt, confusion, missing her, unsure which parent I loved more, which parent I trusted more.

It’s child-of-divorce syndrome. It’s so annoying.

Dad lugs my suitcase out of the trunk, I gather all my bags, and Amy opens the door into the mudroom for us. She wears a face of pity, though I know she’s probably happy my mother is dead. Maybe not happy, but something in the vicinity.

“Oh, come here,” she says, pulling me in for a hug. Her signature smell is comforting, too sweet and too much and yet somehow just right. It’s like inhaling caramel, snorting straight sugar. When she was our dance teacher, everyone wanted to smell like her, to look like her, be like her. Whenever I conjure up her image in my mind, it’s the box blond twentysomething in leg warmers and a leotard, not the stepmother who stands before me, with dark roots and skin specked from gratuitous time unprotected in the sun, wearing kohl eyeliner that’s sunken into her crow’s-feet, and an unflattering sweater tucked into low-rise jeans. Her style never evolved past 2010. I find it equally tragic and endearing.

“Hey, Amy,” I say.

“Let me take your bags,” she says. “Your sisters are in the sunroom.”

“Then that’s where I’m headed.”

She leans in for another hug and says, “I made them some sangria. They might be a little tipsy.”

“Good. They’re more fun that way,” I say, hoping they left some for me.

3

Leda and Daphne are indeed in the sunroom, each holding a near-empty glass with shriveled pink fruit settled at the bottom. There’s a pitcher on the coffee table between them resting atop a cluster of coasters. Leda stands in the corner, a hand on her hip, looking like a mannequin at an Ann Taylor. Her back is to me, her platinum hair in a sleek low bun. She started dyeing it blond in high school to look more like Amy and to spite our actual mother.

Daphne kept her hair dark but chopped it all off into a short wolf cut—close cousin of the mullet. She lies across the couch, her legs draped over the side. She gnaws on an orange rind.

“Heard you were getting wasted,” I say.

They both turn to me, startled, as if awoken from a deep sleep. Daphne jumps up to hug me.

“We’re not drunk,” Leda says, defensive.

“Relax. I won’t tattle,” I say, crossing my heart. “But just so you know, God knows.”

Leda scoffs. She’s not religious; none of us are—we had our fill of “the power of Christ compels you” nonsense in adolescence. She just can’t stand the idea of doing something wrong.

“Don’t tease her,” Daphne whispers in my ear. “She’s fragile.”

“I heard that! I am not fragile. I just don’t think this is a very funny time.”

“You’re right,” I say, wriggling free of Daphne to go hug Leda. It’s unpleasant, like embracing a flagpole.

“You smell good. What is that?” she asks.

“Me,” I say, flipping my hair. I left mine alone. Dark, long, thick, curly. One of the few things our mother gave to us that’s never come up in therapy. When you inherit mostly complexes, why not appreciate the rare gifts? “And Tom Ford. And Oribe. A mix.”

“Mm,” she says, taking a step back to examine me. I return the favor. She’s always had sharp features, but now, in her thirties, her cheeks have hollowed, the angles of her face gone harsh. She has Mom’s epic brows but Dad’s round green eyes. She has Mom’s prominent nose and wide mouth, but Dad’s slight lips and cleft chin. A perfect mix. She doesn’t think she’s pretty because Mom used to tell her she wasn’t, but I love looking at Leda’s face. It’s art.

She clears her throat and takes the daintiest sip of her sangria. “I talked to Helen. There is going to be a funeral.”

“Okay,” I say, pausing in anticipation of details that don’t follow. Instead, there’s a prickly silence.

“We’re not going,” Daphne says. She’s returned to the couch, this time with her feet up on the coffee table, perilously close to the pitcher.

“We, as in you and Leda?” I ask. “And Dad and Amy, I’m assuming?”

“Dad and Amy are not welcome,” Daphne says. “Aunt Helen made that clear.”

“Well, yeah,” I say, circling the coffee table and sitting on the chaise. The afternoon sun streams through the big windows, so bright it’s verging on belligerence. I shield my eyes. “But I want to go.”

Leda sighs a heavy, dramatic sigh. Daphne clicks her tongue.

“It’s gonna be a fucking circus,” Daphne says. “A freak show. You know that, right?”

“I love freaks. I am one.”

“Wearing old Salvation Army wedding dresses on the subway doesn’t make you a freak,” Daphne says, studying the contents of her glass.

“It makes me one of New York’s most stylish people, according to the Times,” I say. They both roll their eyes. “I’m not trying to convince you two to go.”

“Good. Because I’ve already been through this with Tom,” Leda says. “This is my decision.”

“Where is Tommy boy?”

“Upstairs on a work call.”

“Tommy!” I shout. “Maybe he’ll go with me.”

Leda gives me a death glare.

“Fine. I’ll go by myself.”

Daphne shakes her head. She continues shaking her head. Just watching her makes me dizzy.

“Clio …” Leda starts.

“Leda. Leeds. Lee-Lee. Leda-ba-dee-da.”

She purses her lips, sighs again. “I really don’t like the idea of you there. With all of Alexandra’s … strange associates.”

“I’m a big girl,” I say.

It’s Daphne’s turn to scoff.

“What?” I ask, kicking her legs off the coffee table.

Leda interjects before Daphne can answer. “You can’t play the ‘I’m an adult’ card when you still have Dad do everything for you.”

“I appreciate your candor, but you’re wrong. Dad doesn’t do everything for me,” I say. “Just my—”

“Not just your taxes,” Leda says. “Setting up your internet. Mounting your TV. You don’t even have your Social Security number memorized.”

“So?” I ask, and her eyes go wide. I grin. “I’m kidding. I do too have it memorized. Sometimes I just reverse the last two numbers. Whatever.”

“My point stands. You call him for everything. Every little thing.”

“On a phone he pays for,” Daphne says. Traitor.

“You’re still on the family plan, same as me,” I say, tossing a decorative pillow at her.

She catches it. “Yeah, but I pay him. I pay for my phone.”

“Really?” I ask.

“Is this productive?” Daphne says, closing her eyes and hugging the pillow to her chest.

“I don’t know. Is it?” Leda asks, again with the hand on the hip. “You talk her out of it, then.”

“There’s no talking me out of it. It’s our mother’s funeral. I get not wanting her in our lives, not chasing a relationship after everything, but …” I trail off. “Why do I have to justify it to you? I respect your decision. I think it’s a bad one and don’t agree with it at all, but I respect it. Can’t you respect mine?”

“It’s not about respect, Clio. It’s about safety,” Leda says. “You don’t remember what it was like.”

That’s their trump card. I was too young to remember what they remember, too young to comprehend the damage being inflicted. The chaos of Mom fully losing her mind after Dad had enough of her drama and filed for divorce.

“I’m sorry, but I’m with Leeds here,” Daphne says.

“I’m sorry, but I don’t really … care?” I say, standing. “I don’t need your permission.”

They exchange a look of worry and frustration and maybe something else. Heartbreak. I blow them kisses, pick up the sangria pitcher, turn on my heel, and walk out of the room, escaping upstairs, where I can be alone.

* * *

My bedroom is still very much my bedroom, even though I moved out a decade ago, the week after I graduated high school, wasting no time. My bedding is the same old bedding, the art on the candy pink walls all pieces I picked out when I was a kid. Photographs of carousel horses and Paris in the rain. I was a baby romantic who fantasized about a beautiful future filled with beautiful things. A future that is now my present, my reality, mine.

Not this second, though. This second, I get to lie on top of the squeaky double mattress staring at the chandelier on the ceiling, watching the crystals reflect fading daylight, sipping sangria straight from the pitcher, being salty about my sisters.

Bored, I set the remaining sangria on my nightstand and slide off the bed, allowing gravity to deliver me to the floor. I lift the area rug to find the constellation of nail polish stains on the carpet. Proof of a childhood memory, an incident of reckless behavior, the momentary panic of retribution, the realization I could use tears to circumvent punishment, a promise to not do it again, sweet relief.

I’m grateful for it—the proof. The hard evidence. I wish I had more of it with Alexandra. There’s little to validate the memories of my mother. Despite what Dad and Leda and Daphne may think, I do have them—memories—but they’re hazy. Brief and confused, like waking from a vivid dream, one you can’t articulate anything that happened in, only that it happened, and it made you feel intensely.

No stains from my mother. Only scars.

I push up my sleeve and find the remnants of a small burn on my right forearm, the delicate skin above my inner wrist, where my veins are blue and faint and busy. It’s barely noticeable. A little pale, a little rough, the shape of an eye—round but coming to sharp, defined points on both ends. I could never bring myself to blame Mom for the injury, even though everyone else was convinced she was responsible. I don’t remember getting it, only having it. No one was ever keen to discuss the specifics, not Dad, not Amy, not my sisters, and I’ve now forever lost the opportunity to ask my mother.

Though, there is a good chance she mentions it in the book.

Ominous music plays in my head whenever I dare think about the book. Mom’s memoir of our time in the house, Demon of Edgewood Drive: The True Story of a Suburban Haunting. It was moderately successful for all of two minutes, popular among paranormal conspiracy junkies and the like, before they moved on to their next spooky misfortune. The book was optioned for film, and Dad and Leda and Daphne and I all held our breath, fearing an adaptation that, luckily, never came. It’s now long out of print and mostly forgotten. Mostly.

Stricken by a sudden, devious curiosity, I crawl over to my bag and dig out my laptop. I open my browser and Google my mother’s name to see if her death has made headlines or if her brief fame was too niche to merit remembrance. I immediately think better of it and snap my laptop shut, slide it under my bed with my foot like its contaminated.

Promise me you girls will never read it. I’m at the kitchen table. It’s 2009, Leda and Daphne to my left, Amy to my right, Dad standing above us, the look on his face terrifying because he was clearly terrified. I’d never seen him like that, so when I promised, it wasn’t with my fingers crossed behind my back, like usual. I meant it. I’ve kept my promise. I thought it was out of virtue, but maybe it was because I’d never really wanted to read Mom’s book. The idea of it always sincerely freaked me out, having to stare at the ugliest part of our lives in print. Holding our domestic horror story in my hands, in paperback.

Part of me figured we’d all come to terms someday, that Mom would get sober and reach out, apologize, and we’d be in each other’s lives again. I’d get any answers I wanted from the source, and so I had little motivation to ever hunt down a copy, though every once in a while I’d find myself in a bookstore or library checking if they had it on hand. They never did, so I never got the opportunity to run my fingers along the spine and see if it would make me feel anything other than sick.

The urge returns. To Google. To seek an answer for this pesky question. Does anyone else care about her death as much as me?

Does anyone care at all?

I resist the pull of the internet, busy my hands by painting my already manicured nails on the patch of already stained carpet. It’s clear polish, so whatever.

It’s a subpar distraction, and the unanswered questions multiply fast, like rabbits, until they fuse, until there’s just one big ugly bunny. Why do I care?

She abused us, abandoned us, so the story goes. But the details are elusive; the ending is unsatisfying. I resent it.

Eventually, Amy knocks on my door and tells me it’s dinner.

“Be down in a minute,” I say, blowing on my nails so they dry faster. Futile, but I appreciate the guise of power. Of control.

4

Everyone’s already seated at the table by the time I arrive, nail polish dry. Only Tommy appears happy to see me, in his wool sweater with elbow patches, in his round tortoiseshell glasses, the lenses cartoonishly thick. He’s not good-looking, not attractive by any measure—Daphne once described him as having the sex appeal of a raisin—but Tommy is beautiful, radiating this sweet and pure innocence, like a golden retriever or adolescent nerd.

“Tommy!” I say as Dad rises to pull out my chair for me. I catch Leda and Daphne exchanging a look.

“How you doing there, Clio?” Tommy asks, reaching across the table for my hand. He gives it a squeeze, which is a comforting gesture in theory but unpleasant in practice since his hand is so clammy.

“Oh, I’m fine,” I say, smiling.

“And I’m hungry,” Dad says. “Let’s eat.”

“Help yourselves. There’s more of everything,” Amy says. She serves herself some salad and passes the bowl to Leda. Leda will have a small portion of salad and nothing else and no one will say anything about it.

Daphne serves me some chicken without asking. It looks dry, and I’m reacquainted with the frustration of sitting next to my sister, an exceptionally talented chef who has worked at Michelin-star restaurants, who doesn’t cook unless she’s getting paid to do it. Not even for her beloved family.

Both of my sisters’ lives revolve around food, in different ways. This is my mother’s fault, according to them, to my father, to Amy, and I’ve taken their word for it. But now that our mother is dead, I wonder … how? How can she be to blame? She’s not here. She hasn’t been here.

Our family scapegoat is gone. Whose fault will everything be now?

Still Mom’s? A dead woman’s?

The table is quiet, even after everyone’s served and eating. It’s not exactly a comfortable silence. It’s itchy.

“So,” Daphne says, compelled to oust the awkwardness. “Anyone have any vacations planned this year?”

Tommy and Leda are going to Florida to visit his parents, Dad and Amy are going to Big Sur, and I’m going to Paris, London, LA, and Ibiza.

“Paris for fashion week, London for a shoot I’m styling, LA and Ibiza for brand sponsorships,” I say. “For work.”

“Work,” Leda scoffs. She doesn’t take what I do seriously because it’s glamorous. Same with Dad and Amy. Daphne gets it. Tommy doesn’t, but he respects it anyway because that’s who he is. He’s a social worker.

“But before that I’m going to Mom’s funeral,” I say to shake things up.

Dad spits out his sip of water. Amy drops her silverware. Daphne laughs a little, a good sport.

“Where is it, Leeds? Here or in Connecticut?” Mom stuck around for about a year after losing joint custody. She was still permitted visitation, but she’d show up drunk to see us if she showed up at all, and then there was what is known in our family as the infamous “recital incident.” That was the last time I saw her. She put her haunted house on the market and started a new life without us, making no effort to regain any custodial rights, no effort at all, no phone calls or birthday cards, forgoing her mom duties for good. She moved to Connecticut with her demonologist boyfriend, Roy. As far as I know, they’re still together. Or were still together, until yesterday.

Dad clears his throat and says, “Leda.”

“She won’t listen to us,” Leda says. “You have to tell her.”

“You can’t tell me not to go, Dad,” I say. “None of you can. Besides, you’re overreacting. I can handle weirdos. I live in New York City. I work in fashion.”

“We should just let it go. Let her go,” Daphne says, sawing into her chicken. “The more we try to talk her out of it, the more she’s gonna want to do it.”

“What can I say? I’m a rebel.”

“We just worry about you being there by yourself,” Amy says so Dad doesn’t have to. “The people. The narratives …”

“Then I’ll bring someone. A chaperone,” I say, turning my head slowly, until I face directly across from me. “Tommy.”

Tension drops in like an anvil, hard and swift and graceless. Sir Thomas Robert Kowalski turns about as red as a stop sign.

“What do you say? How would you like to finally meet our mother?”

* * *

Everyone comes around on the idea except for Leda, who pouts through the rest of dinner until Dad announces that he’s taking us to Dreamies, a soda shop on Main Street that’s been a family staple for years. It’s impossible to be upset at Dreamies, with all its old-world charm—black-and-white tile floors, tin ceilings, sepia-toned photos on the walls, chrome-and-red-vinyl chairs, banana splits the size of an infant.

Leda, Daphne, and I get a banana split, three spoons. We each take a cherry, holding them up by the stems to cheers. It’s the only time Leda ever indulges, so Daphne and I allow her to eat all the strawberry without complaint, though it’s our collective favorite flavor. Chocolate and vanilla just aren’t as special.

Dad and Amy share a float, and Tommy is lactose intolerant, so he just gets a Coke. They sit at another table, speak in hushed tones, likely discussing the funeral.

“He doesn’t know what he’s in for,” Daphne says. “Poor guy.”

“It’s cruel, Clio,” Leda says. “You shouldn’t subject him to it.”

“He’s seen worse at his job. Real-life horrors. He can deal with a bunch of fake psychics and self-proclaimed witches,” I say, mining for hot fudge.

Leda doesn’t argue because she knows I’m right.

“The banana is the least desirable part of the banana split. Don’t you think?” I ask, attempting to change the subject.

“It’s necessary,” Daphne says. “You’d miss it if it were gone.”

“I would never miss a banana,” I say. “Ever.”

“I think you would,” Daphne says. “I think you absolutely would.”

“What are you two even talking about?” Leda asks, scooping up some whipped cream and offering it to Daphne, who eats it off her spoon.

“Why do we keep getting banana splits if you don’t like the banana?” Daffy asks. “Why not just get a strawberry sundae?”

I gasp.

“We always split a banana split,” Leda says.

“Always,” I say.

“It’s tradition,” Leda says.

“Sister tradition.”

“Okay, all right,” Daphne says, holding her hands up in surrender. “Point taken.”

There’s a lull, a moment of silence. Space for me to start a fire in.

“Have you ever read Mom’s book?” I ask.

“Clio!” Leda says, scandalized.

“What?”

“No, I’ve never read that book. I’ve never wanted to read that book. I don’t even think about it,” Leda says.

“I think about it,” Daphne says. “Sometimes. I looked it up on Amazon once. It’s got a few reviews. Not good ones. Just, you know, wackos who believe in all that. I’ve never read it. I don’t want to either.”

“Don’t tell me you have,” Leda says, pointing her spoon at me. “We promised.”

“I kept my promise. I haven’t read it.”

“Good,” Leda says. “It’s a bunch of lies. Lies making bad memories even worse. I know it’s hard to accept.”

“Accept what?” I ask.

“Who she really was,” Daphne says. “And when you go to her funeral, you’re going to hear stories about her that aren’t true. Not for us, anyway. None of those people were there when we were kids. When we were alone in that house with her.”

I nod, swirling the melty remains of the split. “Do you think she really believed? About the demon?”

Leda says “No” at the precise time Daphne says “Yes.”

“It doesn’t matter,” Daphne says, shaking her head, “if she believed her delusions or not.”

“She was an alcoholic and a narcissist and a terrible mother,” Leda says, setting her spoon down and sitting up straight, lifting her chin. “And I have to be honest—I’m not sad she’s gone.”

After a moment, Daphne says, “Me either.”

“Wow.” I reach up to my neck and fiddle with my new charm, my diamond-eyed snake.

“It’s good we have each other,” Daphne says, eating some banana mush.

“Yes,” Leda says, revealing a small tube of hand sanitizer that she spritzes into her palm.

Daphne and I both turn our hands over, and Leda sprays us, too. She puts the tube away and for her next trick, materializes some lip balm that she passes around the table. We’ve always been good at sharing, never the types to fight over toys or clothes or the spotlight.

Daphne gathers our napkins and carries them over to the trash.

“I’m sorry I volunteered Tommy without getting your approval first,” I tell Leda. “I’m sorry you don’t want me to go.”

She waves a hand. “It’s fine. Might be for the best. You’ll come back understanding what I tried to save you from.”

I blow a raspberry.

“How many times do I have to prove that I’m right about everything?” she says, standing.

“You’re lucky you found Tommy,” I say, leaning back in my chair.

“Ha-ha. Let’s go home. I want to walk off that ice cream before bed.”

We leave Dreamies, Dad chauffeuring us back to the house. Tommy and Leda go for a walk around the neighborhood, Dad and Amy go to bed, and Daphne and I smoke a joint out on the old playset.

We sit on parallel swings passing it back and forth, kicking dirt, pointing out constellations.

“I can’t see shit anymore,” Daphne says, squinting at the sky. “Not without my glasses.”

“Didn’t we used to have a telescope?”

“Yeah. Might be in the basement. I bet Amy sold it, though.”

“Facebook Marketplace?”

“She’s obsessed with Facebook Marketplace.”