4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

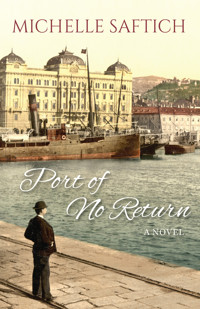

- Herausgeber: Odyssey Books

- Sprache: Englisch

Contessa and Ettore Saforo awake to a normal day in war-stricken, occupied Italy. By the end of the day, however, their house is in ruins and they must seek shelter and protection wherever they can. But the turbulent politics of 1944 refuses to let them be.

As Tito and his Yugoslav Army threaten their German-held town of Fiume, Ettore finds himself running for his life, knowing that neither side is forgiving of those who have assisted the enemy. His wife and children must also flee the meagre life their town can offer, searching for a better life as displaced persons.

Ettore and Contessa's battle to find each other, and the struggle of their family and friends to rebuild their lives in the aftermath of a devastating war, provide a rich and varied account of Italian migration to Australia after World War II.

What can you do when you have nowhere left to call home? Port of No Return considers this question and more in a novel that is full of action, pain and laughter - a journey you will want to see through to the very end.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 360

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Published by Odyssey Books in 2015

ISBN 978-1-922200-29-7

Copyright © Michelle Saftich 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying (except under the statutory exceptions provisions of theAustralian Copyright Act1968), recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of the publisher.

www.odysseybooks.com.au

A Cataloguing-in-Publication entry is available from the National Library of Australia

ISBN: 978-1-922200-28-0 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-922200-29-7 (ebook)

This is a work of historical fiction, inspired by real-life persons and events. Names, characters and incidents have been changed for dramatic purposes. All characters and events in this story—even those based on real people and happenings—are entirely fictional.

For my father, Mauro, and in memory of his family.

Also, for my husband, Rene, and sons Louis and Jimi

Chapter one

January 1944

Fiume, Italy

‘Finally, he sleeps,’ Ettore grumbled as he dipped a chunk of hardened bread into a shallow dish of olive oil. His arms rested upon the wooden kitchen tabletop. A lit candle cast no warmth and only enough light to reach his callused hands. The oil caught the flame’s reflection and glowed; he gazed past the golden orb, unseeing.

‘He’s exhausted,’ Contessa replied. She sat opposite, a shadowy figure in the pre-dawn darkness.

‘Aren’t we all?’ Ettore shook his head. Breakfast done, he scraped back his chair and reached for his coat. The thought of leaving to work on the docks, damp and chilly from the harbour mist, was not appealing, but work he must.

‘I know. I’m sorry. I don’t know what to do. My milk only upsets him,’ Contessa despaired, not for the first time. She had left their three-month-old baby asleep in a bassinette in their bedroom, lying still—too still for her liking. His scrawny, closed fists flanked pale cheeks and his eyelashes had become mere clumps of moist spears attached to red and swollen lids that had borne too many tears and an unrelenting torrent of squalls and wails, keeping them awake all night, every night. But for now he slept.

‘There’s something we can try,’ came a husky voice from the darkness. Contessa’s mother, Rosa, the family’s revered Nonna, was desperate to raise the parents’ hopes. Coming out of her bedroom wrapped in a woollen shawl, she had caught her daughter’s last words. She lit another candle, a larger one, and carried it towards them, chasing away the shadows.

Nonna was a tall, broad woman, olive skinned and robust, with long, coarse, black hair often caught in a crocheted net at the nape of her sturdy neck. This early, however, it hung like a curtain down the full length of her back. She had never been beautiful, but was handsome and well respected in their north Italian neighbourhood.

‘I’ve tried everything,’ moaned Contessa, exhaustion making it difficult to believe in solutions. Like her baby, she too was losing weight—though in her case it was from long hours on her feet nursing, cradling, and comforting her irritable son, while she sacrificed the greater portions of their meagre food supplies to her other children. Occasionally, Nonna would give her a break, but the baby only wanted his mother and remained unsettled in her arms.

Contessa’s wool dress was covered in milky sick-ups, her hair—fairer and finer than her mother’s—was frizzy and hard to pin back. She had not tended to it in days, leaving it spongy as fairy floss. The tendrils surrounded an almond-shaped face, drawn and weary, and her dark brown eyes struggled to keep open.

‘Ah, but you haven’t tried everything. You haven’t tried my minestrone soup …’

‘Minestrone!’ Contessa was incredulous.

Despite his glum expression, Ettore smiled, squeezing his wife’s tense and bony shoulders. ‘You should listen to your mother. She knows …’ he said. ‘Now I best leave before the kids wake up and make me late.’ He kissed Contessa on the cheek, but she couldn’t smile.

‘I don’t know about soup … too rich for him. He’ll bring up red sick everywhere.’

‘Let me try,’ insisted Nonna.

‘Let her try,’ Ettore agreed.

As much as she wanted to, Contessa didn’t have the energy to argue. ‘Okay, we’ll try it.’ She stood and kissed her husband on both cheeks. ‘Ciao and keep safe,’ she whispered.

Ettore wanted to heed her words, but these were not peaceful times. The war had brought years of devastation to Italy, and to Europe. For Ettore, it meant having to work for the Germans who had taken over their city in Italy’s north-east. They lived in Fiume, a city the Germans had wanted for its strategically placed seaport. The city had also provided the Germans with many industries to support their war effort, including the oil refinery, torpedo factory and shipbuilding facilities. In the face of the occupation, the residents of Fiume had only one choice—to serve the heavily armed Germans.

Keep safe—and serve, Ettore thought sourly.

‘Ciao,’ he replied. He closed the door gently on his household of sleeping children. Apart from the sleeping baby, tucked up in their beds were six-year-old Taddeo, three-year-old Nardo and Marietta, aged two.

Rubbing sleep from bloodshot eyes, Ettore ambled down the familiar front steps and onto the cobblestone street, before making the steep and foggy descent to the port. The sun was rising, and he welcomed the light filtering through the mist. He thrust his frozen hands into his coat pockets and hunched his shoulders forward to cut through the icy air. Occasionally he peered through the window of an empty shop or a closed boutique or a boarded up school. On one corner was a century-old administration building that had been cracked apart and left to crumble away, the result of a bomb dropped from the sky a few months ago. The closer he got to port the more destruction he saw. War had come to this beautiful city—a city rich in Hungarian architecture, and old enough to boast ancient relics including an arched Roman gate. The presence of German troops had ensured that Fiume, its port and facilities, had become the target of deadly Anglo-American air raids—dozens of them.

His purposeful stride soon brought the port into view. Majestic four- and five-storey buildings fronted the harbour, including a grand old dame of a palace built by a Hungarian shipping company. It now overlooked a hectic display of vast, towering warships and raised submarines. German and Italian soldiers patrolled the decks of the ships and marched in unison down on the quays. For a moment, Ettore looked back at the city, where hills dotted with houses loomed—along these hilltops a line of cannons pointed towards the sky. Would they need them again? He prayed not.

He was early to work, preferred to be, for the Germans were strict when it came to clocking in. It was his job to help pressure test the submarines, find leaks and repair them. Not a bad job, but once the fully operational submarines left, crammed with men destined for naval combat, he did not like to dwell upon the poor bastards’ futures. It was not a good way to die.

When he reached his station that morning, he did not even get a chance to clock in. The emergency sirens erupted, their shrill warning blaring across the entire city. Instantly, soldiers and workers were running in opposite directions. While those in uniforms raced to take up arms to defend the port, unarmed men scurried single-mindedly to the safety of bomb shelters. The words ‘keep safe’ rang in Ettore’s ears, but he was no longer thinking of himself. Instead, he pictured his baby Martino at home, peaceful in exhausted slumber. He thought of his other three children, and of his weary but lovely Contessa and dependable Nonna. They would be hearing the sirens too. No baby could sleep through that racket.

‘Keep safe,’ he mouthed, almost out loud, but he was gripped by a sense of dread that would not leave him. ‘Keep safe.’

* * *

Contessa had been standing at her second-storey window looking down on their front drive, where two petrol bowsers sat collecting dust. It marked the entry to her husband’s workshop, where he had toiled for many years as a mechanic. Once a hive of activity, the business was deserted. It had been abandoned when Ettore had been conscripted into the Italian war effort. She remembered how nice it had been to have him downstairs, chatting to regular customers, bringing in enough money to buy fresh foods and small luxuries. They used to have a good, relaxed lifestyle—lazy mornings and late nights with friends. Back then her babies had suckled well and slept soundly. Laughter and feisty conversations had filled the house.

Contessa lifted her gaze. The early morning mist had evaporated to reveal clear skies; she could not help but notice that it was a perfect day for bombing. She tensed with apprehension and instantly regretted the gloomy thought. It would be a nice day, she assured herself. Contessa did not know what had drawn her to that spot, to look upon their cobblestone street, their neglected shopfront, to remember times before the war. From the window she could see the harbour—a bluish grey mirror reflecting sky and ships—and she wondered, with a sense of unease, what Ettore was doing. As she gazed out, she felt sadness weigh her down. The lack of sleep perhaps? And yet it felt stronger than just fatigue, closer to fresh grief—as if she was about to experience a deep loss. Looking back, it was as though she knew it would be the last time she would take in that view.

The sound of her children squabbling brought her away from the window and into the kitchen.

‘I was here first,’ six-year-old Taddeo whined.

‘You had it yesterday,’ cried Nardo.

The brothers were wrestling, their fair-skinned limbs entangled in a purposeful struggle. The subject of their battle was a chair. Its position close to the cast iron stove had made it popular. Marietta, the youngest of the trio, stayed out of it, sitting the farthest from the stove but content to be eating her torn-off piece of oil-moistened bread.

‘Stop pushing,’ Nonna said sternly. Stirring the soup, she feared the boys might knock over the pot and spill its simmering contents on themselves. She had wanted to make minestrone, but it had turned out to be a very thin version—just canned tomatoes, water and a pinch of salt. Thanks to the war food was scare, and their measly rations could only be supplemented with what they could find on the black market.

‘Can’t you see this is hot?’ Nonna admonished.

‘But I was sitting here …’

Contessa swept into the room. ‘Stop it, both of you! Taddeo, sit over there. Now! It’s Nardo’s turn.’

‘But Mama …’ Taddeo started.

‘I’ve told you. Now move. All this fighting will wake Martino. How many times have I told you not to make too much noise when …’

Her call for quiet was ironically and comprehensively drowned out by the shrill blast of sirens. Fear and dread clutched at her already strained nerves. Her baby son awoke instantly with a piercing cry that matched the siren’s intensity.

‘Martino,’ she shouted, bolting to her bedroom. From there she called back to her other children. ‘Taddeo, Nardo, Marietta—grab your coats.’

By the time she had gathered up her baby and reached the front door, her other children were assembled, coats in hand.

‘Put them on,’ she instructed.

They did not need to be told twice. Despite their young ages, the children knew the drill and understood the importance of reaching the dugout shelter quickly. They were afraid, but didn’t cry. The baby was crying enough for all of them.

‘Nonna,’ Contessa called.

The older woman rounded the corner with a glass baby bottle full of hot soup. She took her full-length coat from the rack by the door and slipped into it, then handed Contessa hers. While the day was fine, it was bitterly cold and they would need the protection of their woollen overgarments. Rugged up, they hurried outside.

‘Nardo, stay with me,’ ordered Taddeo, taking hold of his younger brother’s hand. Their fight over the chair was completely forgotten.

Nardo gratefully clutched the hand that had wrapped around his, relieved to be guided through the chaos that the sirens had created. The two brothers kept their eyes on Nonna, who led little Marietta across the mossy cobblestones towards the church, three blocks away. The streets were overcrowded with people, all hurrying in the same direction, all with the same stern expression on their faces. Once in the churchyard, the boys followed their mother and Nonna into the shelter and joined the other families, mostly women and children, piling inside.

It was dark and musty in the dugout, but no one complained. Martino was still crying—a pathetic, hungry and urgent wail that did not help to settle the panic-stricken people bunkering down. Desperately, Nonna took the baby from Contessa’s arms and put the bottle of cooling soup to his lips. She prayed he and his frail little body would accept it. He took a suck … and another and another. He was silenced—at last. Content to be sucking on the sweet, warm juice he’d been offered, he was finally in a rare and blissful state—awake and quiet, simultaneously. Nonna looked at Contessa, whose brown eyes held tears of relief.

‘It will be all right, Mama,’ Taddeo said, misreading his mother’s tears.

‘I know, darling. I know,’ she said, cupping his tiny face in her hands and planting a kiss on his lips. ‘Thanks for looking after your little brother.’

She looked at Nardo, who was tall for his three years. His dark eyes were shining, but he emitted a calmness that even she could draw strength from. ‘My brave Nardo,’ she mouthed to him.

Across from her, clinging to her Nonna’s coat, was Marietta, a chubby-cheeked girl with a head full of black curls and a prominent beak-like nose. Fear had rendered her still and silent.

Beyond the siren, they could hear the planes approach—a distant buzzing, which quickly grew into an alarmingly loud roar. Then the bombs started … one, then soon after another, and another.

Oh God, thought Contessa as the ground trembled. So close.

There was a collective gasp among the women as the bombs fell again—too near. Contessa looked to Nonna, but her eyes were shut. Being Roman Catholic by faith, she sought solace through a murmured Lord’s Prayer. ‘And forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us …’

More bombs … their world was shaking, the blasts above loud and violent. It was the worst air raid to date and Contessa was terrified. Her boys sat closer, pressing their trembling bodies against her own. Please stop, she thought. How she wished Ettore was with them—it would be better to be together if anything should happen.

At last, the thunderous roar of the planes subsided, gradually fading until the sound was a distant hum. All was still. The sirens ceased. Someone in the shelter was crying—a frail, wrinkled old woman dressed in black, overcome by emotion. It added to the communal sense of despair. Whatever awaited them outside could not be good. They knew their part of town had not been spared this time. They waited, longer than perhaps was necessary, but shock had rendered them immobile. Eventually a few families ventured out.

‘Come,’ Contessa croaked to Marietta and the boys. They leapt to their feet, eager to follow their mother.

Nonna stood too, pressing the whimpering baby against her chest.

After so long in darkness, they emerged, quiet and still in the bright light. Even baby Martino had gone silent. Blinking, they became aware of the full extent of the surrounding damage. They shuffled home, their eyes wide with disbelief as they took in crushed houses, blackened and cratered yards and crumbled stone walls—occasionally a body could be seen beneath rubble and a wail of a loved one echoed in the distance. An old man was being helped away from the wreckage, blood gushing down his face.

Contessa buried Marietta’s face against her coat in attempt to shield the toddler from the worst of it. She looked behind and saw her sons holding hands, their heads down, watching only their Nonna’s feet as she walked in front. They had already seen enough to not want to look.

Such devastation! Contessa had not expected it to be on such a scale. Fear for her house, her neighbours and friends set in. She picked up her pace, Marietta stumbling alongside as they picked their way around houses and walls that had slid into the street. Plumes of dust scratched their eyes and stung the backs of their throats. Everywhere there were sharp, jutting objects to be avoided. Away from the bulk of the debris, their feet manoeuvred around uneven concrete and brick blocks, shattered glass, fallen street lamps and broken clay pots, window shutters and cracked roof tiles.

Home for Contessa was pegged by a strong, lean figure, simply clad in grey coat and trousers, standing, head bowed, where once a house had stood. He was in his thirty-fourth year of life and should have been reaping all he had sown. Instead, the man appeared crushed, defeated. On hearing their approach, he turned.

‘Ettore …’ Contessa exhaled, her parched throat struggling to cry out her husband’s name. He saw them and his eyes darted from face to face, accounting for each member of his family—only then could his legs find enough strength to stumble over. He picked up Marietta, whose black curls were littered with bits of paper and dust, and he noticed her cheeks were moist from tears, accompanied by frightening silence. He embraced the child, held her tightly and planted a kiss on her dark head, before plunking her safely on his shoulders. He ran his hand affectionately and roughly through his boys’ thick hair. Then his eyes rested on the baby, at peace in his Nonna’s arms. Relief that his family had escaped to the shelter momentarily replaced the devastation of finding his home, his business, all he had worked for, gone. There was nothing left. Nothing. Unlike other houses, theirs had disintegrated. No doubt the petrol bowsers and grease-filled workshop had fuelled the utter destruction.

‘Where will we live now?’ Nardo asked. His small voice quavered.

No one answered, but his father reached out and pulled him against his side.

Contessa surveyed the blackened hole in the ground then closed her eyes to it. What will become of us? she thought. We’ve lost everything.

Chapter two

January 1944

Farmhouse, outskirts of Fiume, Italy

The Coletta family lived at the foot of a hill on the outskirts of Fiume, a short walk from the end of the tramline. They had a farmhouse with chickens and goats, as well as a productive beehive and vines of luscious tomatoes.

In the past, their cellar had held the fruits of their labours: cheeses and cream made from goats’ milk, jars of honey and stewed tomatoes and cartons of eggs - until the Germans took over the city. Soldiers quickly became regular, uninvited visitors, demanding they hand over their stores to feed the troops.

‘You want to support the war effort, don’t you?’ they challenged. ‘Come on then. Make a contribution and make it generous.’

Even after their generous contribution, the Germans would help themselves to three or four of their precious chickens as well.

The last time the soldiers visited there were only two sickly chickens to be found.

‘They are all we have left,’ Lisa told them mournfully.

They took them anyway. In truth, Lisa’s husband had staked a lookout for the Germans. On seeing them approach, he had walked three strong goats up into the hills and carted away a large crate of healthy chickens. He had stayed hidden until the Germans were long gone.

‘It worked,’ Lisa told him happily on his return. ‘They searched the cellar and didn’t find anything. They searched the storage house—nothing again. They didn’t like the look of those chickens and I told them they were our last.’

‘Good. Hopefully they’ll take us off their list and leave us alone.’

The soldiers returned one more time, but again, they hid their chickens and goats up the hill and the Germans left empty-handed. That had been four months ago.

It was mid-afternoon, and Lisa was sitting outside, plucking the feathers of a large waterfowl bird that her husband had caught by chance that morning. Head bowed in concentration, she was surprised to hear the front gate squeak, followed by the scraping of light footsteps. The knock on the front door was not the usual brisk, hard sound of the Germans’ pounding so she did not believe she had soldiers on her doorstep, but she was not expecting guests. She was nervous, but intrigued.

Could it be a telegram? Her nineteen-year-old son, Marco, was away fighting, and a tragic delivery was always a possibility. But she had heard several footsteps.

Could it be her youngest son, Cappi, with comrades? He had run off with the Yugoslav Partisans, deciding it was better than being called up to fight for the Germans. When the Germans took over Fiume, they had rounded up all the young Italian men not yet at war, and sent them straight to the front line and almost certain death. Fearing such a fate, her son had fled into the hills and left it to his family to spread the false tale that he had become a commercial fisherman and left for sea. He had returned once, looking for food and warmer clothes.

Her husband, Dino, was at the markets and their sixteen-year-old daughter Lena was at work in the city and not expected back until dark.

Lisa took a deep breath and walked down the side of the house to peer around the corner suspiciously. Two women and a few children were huddled on the doorstep, a bedraggled lot, with tousled hair and long dusty coats.

‘Can I help you?’ she called, no longer harbouring any fear of her guests.

The younger woman turned and Lisa recognised her instantly—Contessa Saforo.

‘Contessa!’ Lisa cried, hurrying towards her friend, who only managed to return a wan smile in greeting. The sad-eyed woman held a baby, and around her were three tired children and her formidable mother.

‘What has happened?’ she asked, her voice thick with concern. Because of the war, she had not seen her friend in over a year.

Contessa, even with a grubby face and tangled hair and in obvious distress, was still a picture of loveliness, as she had always been.

Lisa envied her friend her gentle beauty and grace. Unlike Contessa, Lisa was somewhat brisk and bustling in her manner. At thirty-five, she was six years older than Contessa, but had started her family much earlier, giving birth to her first child at age sixteen. A strong, buxom woman, she had worked hard on their farm, especially during the war. Although the hard labour, hot sun and deep angst over her sons at war had toughened her skin, beneath it still laid a soft heart.

When her friend hesitated, Lisa waved her hand. ‘Please come in.’

The dazed family shuffled inside and Lisa stifled an urge to wrap her arms around them all. ‘Come sit down.’

She ushered them into a spacious room, which featured stone walls and floor, and a high ceiling with exposed oak beams. Black cloth hung from the windows for use as blackout curtains; the windows were taped up—a necessary precaution given the bombings. Along the left wall was a massive stone hearth. The children sat before it on a large, woven rug and Contessa and Nonna sat on a soft, but rather worn yellow sofa.

‘It was the bombing …’ Contessa began, wanting to explain their uninvited intrusion.

‘Ettore … is he all right? He is not with you?’

‘He is safe. He is at work.’ She hesitated. ‘But everything else, the house, our life, it is gone,’ she said, tears in her eyes. She paused to compose herself, and then continued. ‘We have nowhere to go. My sister is in Bergamo. We have no other family here. My mother, as you know, lives with us. We lost everything.’

Lisa’s heart went out to her. ‘You did right to come to us. We have plenty of room. Please don’t worry. You are all welcome to stay … until the war is over.’

Her last words revealed a generosity of such magnitude that Contessa could no longer contain her emotion. ‘Oh no, Lisa. You are much too kind,’ she said, wiping at tears that kept flowing. ‘We couldn’t stay long,’ she sniffled. ‘I only came to ask for one night’s stay.’

‘One night—and then what? Ask another friend and another? Moving your children and baby from house to house so as not to overstay your welcome? Don’t be crazy! You must stay here until you have a real plan.’

‘But we are a big family …’

‘Which is why you must accept my offer.’ Lisa was adamant.

Contessa felt Marietta tugging on her dress and looked down.

‘Please Mama. I like it here. They have goats.’

Lisa smiled broadly. ‘You remember my goats. Bless you child but it’s been a year and many months since you last visited. They must have made an impression on you. We still have three.’

‘Do you have the one called Milksha?’ the girl asked, flicking her black curls out of her eyes.

‘Yes. She is the playful one. Why don’t you children go out in the yard and see? Just remember to keep the gate shut.’

Marietta danced towards the door. ‘Come on,’ she said to her brothers.

Taddeo looked up at his mother. ‘Is it all right if we go outside?’ he asked solemnly. The boys had been quiet and troubled since the bombing.

‘Of course. Go see what else you can find,’ their mother urged, wiping her damp hands on her dress, rimmed with ash from the burnt-out rubble.

‘There are chickens. But keep away from the bees,’ Lisa advised.

‘I remember the bees,’ Taddeo said with a smirk, having been stung at the last visit after venturing too close on a dare from his brother.

‘They won’t bother you if you don’t bother them.’

‘I won’t,’ Taddeo assured her.

Marietta bounded outside while her brothers followed slowly.

‘The boys are feeling the shock, but Marietta is too young to understand,’ Nonna said, once the children were out of earshot.

‘War is no place for children,’ Lisa said, understanding. ‘The boys are young and strong. They will recover in time. Let them stay here. There is the small stone house out back …’

‘But that is for your stores,’ Contessa said, not wanting to cause any disruption.

Lisa shook her head and lowered her voice. ‘Up until two weeks ago, we were hiding a Jewish family in there,’ she confided.

‘Jews!’ Nonna gasped, her voice barely above a whisper. ‘You took such a risk!’

‘They were our friends and we couldn’t let them be loaded on the trains. There was a risk, but the Germans have been leaving us alone and we always had someone on lookout. They’ve now escaped, heading for southern Italy. I pray they got there. So, the point is—the house is ready and comfortable. It has a fireplace, which you can use for warmth and cooking. We have plenty of firewood.’

Contessa looked to Nonna who nodded her head.

‘We would love to stay,’ Contessa said, and her heart lifted with relief.

‘It is only right that you do. I could never turn you away. Now come and I will show you the house. It’s small, but it has two rooms and is clean and dry.’

The women inspected the house and were very pleased with its simple but comfortable furnishings. As they looked over the cups and plates in a small cupboard, Martino started to cry.

‘We have only one baby bottle,’ Contessa said.

Nonna held up the empty glass bottle that she had been carrying in her coat pocket since they left the house the day before.

‘He does not take the breast?’ Lisa inquired, knowing that her friend had breast-fed all her previous children.

‘He won’t take milk,’ Contessa said, in a sigh that revealed some of her exasperation.

‘Tomato soup …’ Nonna cut in.

Lisa smiled. ‘Tomato soup! Mercy! This baby likes it sweet, hey? Luckily, we’ve plenty of tomatoes—though the jars are hidden.’

‘The Germans …?’

Lisa nodded. ‘Let’s get that hungry baby fed,’ she said as Martino’s cries increased in volume.

Contessa nursed the baby to keep his cries under control while the other two went to work in the kitchen. Soon, they had enough tomato soup to keep the baby fed for two days. Martino was silenced. Peace had returned. With the highest priority sorted, they then turned their attention to freshening up the storehouse and helping Lisa prepare that night’s meal. Nonna put her talents in the kitchen to good use. Excited to be working with more ingredients than she had seen in a long while, the older woman set about making stuffing for the bird and preparing a tomato-flavoured gravy to accompany it.

When Lisa came into the kitchen, she was pleasantly surprised.

‘You can stay as long as you like,’ she enthused, inhaling the savoury aroma. ‘Look at that! I can’t wait to serve this up to Dino.’

‘How is your husband? It has been—what, four years since we last saw him?’ Nonna inquired.

Their families used to get together regularly, but once the war had broken out, they had not socialised—night curfews, blackouts, raids, food shortages and late work shifts had not made it practical to make the journey across town for a dinner party. Lisa and Contessa had still managed to meet up during the day but even those visits had become less frequent.

‘He is well. Tired of the war, but well enough.’

‘That is good to hear. I would change for dinner but we have only the clothes we have arrived in. The children have only their coats and bed clothes.’

‘I can lend you some clothes for now. Though tomorrow we should visit the local church. I know they are helping families to replace clothes and other things,’ Lisa said. ‘It’s a short walk from here.’

‘Thank you. I think we’ll have to ask for a handout from the parish,’ Nonna said, feeling embarrassed. ‘I have often given.’

‘Then it is your turn to be helped.’

Lisa’s husband Dino arrived home an hour after the sun had set. Ettore arrived about ten minutes later. They had caught the same tram, yet not seen each other, and it had taken Ettore longer to recall the way to the house, having last visited it several years ago.

Contessa had assured her husband they would be able to stay at the farm for at least one night and had arranged to meet there come nightfall, but she was delighted to inform him they could stay as long as they needed.

‘Are you sure?’ he pressed, surprised at such open hospitality.

‘I’m sure. Lisa would not let me refuse!’

Dino was also surprised but proud of his wife for taking in the homeless family. He found her in the kitchen, looking happy yet flushed from the heat of the fire burning in the stove. ‘We’ve only just farewelled the Jews, now it’s your school friend,’ he whispered to her good-naturedly, while she stirred Nonna’s thickening sauce. ‘You have a soft heart.’

He kissed her moist cheek. ‘Dinner smells incredible,’ he said, trying to see what was simmering. His cheeky face and ready smile were trying to charm her into an early sample.

‘Just wait. Go wash your hands,’ Lisa told him. ‘We are serving up in minutes.’

The short, dark-skinned man chuckled as he reluctantly retreated from the kitchen. As instructed, he washed his hands then ducked out on the porch, despite the chilly night. He waved at Ettore to follow him.

‘Here,’ Dino handed his friend a cigarette. He had acquired a packet on the black market early that morning. Cigarettes were hard to come by. He had been looking forward to smoking one all day and would enjoy it even more in being able to share the moment with an old friend.

‘Light up,’ he said giving him a matchbox.

Ettore was impressed. A cigarette! A rarity! He smoked it and smiled.

Dino struck the match proudly. ‘One of the few joys left to us these days,’ he muttered, lighting up and inhaling deeply. ‘Ah.’

‘We take what we can,’ Ettore agreed.

‘Damn war.’ Dino recalled Ettore had had a fine house on a hill and a large workshop beneath a floor of three bedrooms. It was hard to imagine it was no longer there. He recalled many a good meal enjoyed in their kitchen served with Nonna’s homemade liqueurs, but that was a long time ago.

‘Your children—Marco, Lena and Cappi—how are they?’ Ettore asked. The last time he had seen Lena she was twelve years old. ‘Your daughter must be what—sixteen now?’

‘She works all day at the torpedo factory and then does a night shift. She won’t be home until after midnight.’

Ettore was not surprised. It was common for the young ones to work two jobs, but he was sad to hear that the young woman worked in such a dangerous place—a key target of the air raids. She was a nice girl and kind to his children. He knew they were looking forward to seeing her.

‘That is no good,’ he told his friend. ‘I pray she keeps safe. And how is the farm?’

‘It has its challenges. With food rations the way they are we are lucky to have the extra food and we do well at trading on the black market. But our honey draws German soldiers faster than flies.’

Dino took a long drag on the cigarette. ‘And my son Cappi is still with the Yugoslav Partisans. They are killing off the odd German and Italian soldier. Cappi has managed to stay out of it—for now. If it comes to full-scale battle …’

‘When it comes to battle,’ Ettore observed.

‘You are right. When the Germans weaken, the Yugoslavs will make a grab for our city and then my Cappi will have to come home.’

‘The Partisans are not organised though.’

‘No. But they will be.’

The men considered what a Yugoslav assault would mean to Fiume and shuddered in the chill of the night. The majority of the city’s population, more than eighty per cent, were Italian, though the surrounding suburbs and a nearby town were Croatian.

Fiume had once been ruled by Hungary, but with the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy at the end of World War I, it had become a city under dispute, with both Italy and Yugoslavia putting in a claim. After a period of strife and intense diplomatic negotiations, a peace treaty eventually assigned its governance to Italy. However, the Yugoslav neighbours had never taken their eyes from the prize, and another chance was looming.

‘Any news of Marco? He is away fighting?’

‘No news. No news is good news.’

The cigarettes were finished. The men stood silent in the dark, their thoughts even darker.

‘Time to go in,’ Dino said at last—the aroma of garlic and tomatoes too enticing to ignore any longer.

The meal was the best the Saforo family had consumed in a long time. Even Lisa and Dino were elated to have a different and flavoursome meal before them. Slices of roast bird were served alongside mushroom and goat cheese stuffed tomatoes.

‘Yummy,’ Marietta said, sauce spread from cheek to cheek. The bird was similar to chicken, its skin crisp and its meat juicy.

Afterwards, the families shared the warmth of the fireplace and took turns telling the children stories. Their stomachs were full, their faces flushed, and the joy of good company put them all in good spirits. It was just what Contessa had needed.

* * *

While her family relaxed by the fire, sixteen-year-old Lena was hard at work, polishing the torpedoes until they shone, using one hand and then the other, until both wrists felt strained. But on that night, it was not just her hands giving her cause for pain. She had a bad toothache—one that was becoming harder and harder to ignore.

Lena had dreamed of being a dressmaker, and had been learning the trade when the war broke out. After the Germans occupied Fiume, she was rounded up with the other young people and assigned work. Her task was to shine weapons that would then be loaded on to trains, destined for Trieste, where they were transported to Germany for use in the war. As she polished, she wondered how many lives, how many ships they would destroy. Sometimes, she would catch her own reflection on the shiny casing and be surprised at the depth of the sorrow she would see in her eyes.

After a long day in the factory, she had to attend to her night work and walk to a large hall, not far from the port, to help serve food for up to one thousand workers, finishing their late shifts across various city posts. It was exhausting, even for a girl of her age.

It was eleven o’clock at night and her shift wouldn’t end for another hour. Lena was now in sheer agony. She clutched at her jaw, trying to press down on the throbbing, unrelenting ache, her face contorted in pain. Her obvious discomfort eventually caught the eye of her matronly supervisor—an Italian nonna, who made no secret of the fact that she felt sorry for all her young charges.

‘What is wrong?’ she asked of the tall, slim girl, whose green-flecked eyes were wide and troubled.

‘My tooth,’ she replied, hardly able to speak.

The matron, whose hair was plastered against her forehead from hours spent sweating over bubbling pots, wiped her brow and glanced up at the clock. ‘Why don’t you go home now? We can finish up here all right.’

‘Thank you,’ the serving girl managed to mumble through her clenched jaw. The pain was such that Lena, after pulling on her coat, chose to wrap her woollen scarf around her head and beneath her chin to apply pressure to the tender site. She caught the second last tram and disembarked at the end of the line. Home was only a short walk away.

It was close to midnight, and her blistered feet scurried along the street, eager to be home. However, as she turned the corner, two uniformed men came into view. It was dark and no one else was about. Usually when she caught the last tram, it would be crowded with workers finishing the late shift and she would walk home with a few others heading in the same direction. Catching the earlier tram had meant alighting by herself. She slowed her pace and pulled her scarf tighter around her face, hoping to hide her youth and prettiness from their prying eyes. In the low light, she was unable to tell if they were German or Partisan, and she felt her skin crawl with apprehension.

‘You there! Where are you going at such an hour?’ they demanded to know in Yugoslav, which set her heart pounding fearfully. She did not understand them, but knew they were questioning her. The German soldiers had been ordered not to harm women, but the Yugoslav Partisans were under no such policy.

‘I’m sick,’ she said in Italian, then again in German, hoping they would understand one of the languages.

They studied her for a long moment and talked between themselves.

As they conversed, her fear grew. Despite her long legs, she did not think she could flee or outrun the men. Trembling, she kept her face lowered and waited.

‘Take off your scarf,’ one of the men said.

She looked at them helplessly, not understanding.

The gruff, thick-necked man strutted over and wretched the knitted item away from her, so they could get a full view of her face.

‘She’s very pretty,’ he said admiringly, his dark eyes squinting.

‘A pretty girl alone at night must be looking for something,’ the taller one said, licking his fat bottom lip and gawking at her breasts.

Lena felt their eyes raking over her body. She crossed her arms and tried to take a step forward, away from them.

The tall man grabbed her roughly by the arm and she let out a small yelp of pain and panic.

A voice, strong and forceful, boomed across the street.

‘Unhand her.’ The command was given in Italian. The Communist soldiers, unshaven and uncouth, turned, ready to knock down whoever had dared to interrupt their play. They never saw him. The short man went down first—a thick staff of wood slammed into the back of his head and, with a bone-chilling crack, he slumped to the ground, unconscious. The other watched his comrade collapse and, not wanting to take on such a capable foe, fled. He released the girl and ran into the darkness, his boots crunching on gravel in the distance.

‘Not so brave now,’ the Italian commented. Lena glanced at the man who had come to her aid so swiftly. He looked familiar, but it was dark and she couldn’t make out his face. She gathered that he was about the same age as her father, perhaps a few years younger. He wore a nice coat and the outline of his features reminded her of Humphrey Bogart, the famous actor—whose poster had been in the window of the city cinema.

‘Thank you. Thank you,’ she breathed. Her tooth shot a stab of pain through her jaw and her hand flew to it.

‘Are you hurt? Did he hit you?’

‘No. My tooth.’

The man smiled kindly, picked up her scarf and handed it to her. ‘Come. We best get moving before he wakes up. I’ll walk you home,’ he turned her in the direction of her house and they started to walk briskly.

‘You know where I live … and I know you,’ she said, wincing as she spoke.

‘Yes. My name’s Ettore. I haven’t seen you for a few years. My family is staying in your farm’s storehouse. You are lucky I couldn’t sleep. Our fire had burned low and I came down this way to search for more firewood.’

He waved the wooden staff that he had used as a weapon, indicating it was meant for the fire.

‘Ettore … you are Contessa’s husband! I know you. Ouch.’

‘Stop talking. We will get that tooth looked at. Nonna should know just the trick for easing your pain.’

Lena smiled as best she could. ‘You went the wrong way for firewood.’

‘Lucky for you.’

* * *

The next morning, right on sunrise, Ettore awoke. He was alone on the mattress. Where was everyone? Why hadn’t Contessa woken him?