9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

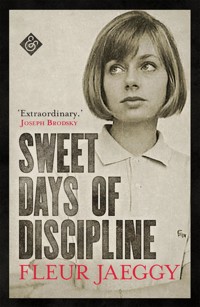

- Herausgeber: And Other Stories

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A fifteen-year-old girl and her father, Johannes, take a cruise to Greece on the Proleterka. Jaeggy recounts the girl's youth in her distinctively strange, telescopic prose: the remarried mother, cold and unconcerned; the father who was allowed only rare visits with the child; the years spent stashed away with relatives or at boarding school. For the girl and her father, their time on the ship becomes their 'last and first chance to be together.' On board, she becomes the object of the sailors' affection, receiving a violent, carnal education. Mesmerised by the desire to be experienced, she crisply narrates her trysts as well as her near-total neglect of her father. Proleterka is a ferocious study of distance, diffidence and 'insomniac resentment'.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 131

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

This edition is the first UK publication. It was published in 2019 by And Other Stories Sheffield – London – New Yorkwww.andotherstories.org

First published as Proleterka in 2001 by Adelphi Edizioni S.P.A, Milan © 2001 Adelphi Edizioni S.P.A., Milan English-language translation © 2003 by Alastair McEwen This translation first published in 2003 in the USA by New Directions, with the title SS Proleterka.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transported in any form by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher of this book. The right of Fleur Jaeggy to be identified as author of this work and Alastair McEwen as the translator of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or places is entirely coincidental.

ISBN: 978-1911508-56-4 eBook ISBN: 978-1911508-57-1

Proofreader: Sarah Terry; Typesetting and eBook creation: Tetragon, London; Cover Design: Edward Bettison.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This book was supported using public funding by Arts Council England.

Contents

ProleterkaProleterka

Many years have gone by and this morning I have a sudden desire: I would like my father’s ashes. After the cremation, they sent me a small object that had resisted the fire. A nail. They returned it intact. I wondered then if they had really left it in his suit pocket. It must burn with Johannes, I had told the staff of the crematorium. They were not to take it out of his pocket. In his hands it would have been too visible. Today I would like his ashes. It will probably be an urn like any other. The name engraved on a plate. A bit like a soldier’s dog tags. Why was it then that it had not occurred to me to ask for the ashes?

At that time I didn’t use to think about the dead. They come to us late. They call when they sense that we have become prey and it is time for the hunt. When Johannes died I didn’t think he really died.

I took part in the funeral. Nothing else. After the service, I left right away. It was an azure day, everything was done. Miss Gerda saw to all the details. For this I am grateful to her. She made an appointment with the hairdresser for me. She got me a black suit. Discreet. She scrupulously complied with Johannes’s wishes.

I saw my father for the last time in a cold place. I bade him farewell. Miss Gerda was at my side. I was dependent on her for everything. I did not know what one does when a person dies. She had a precise knowledge of all the formalities. She is efficient, silent, timidly sorrowful. Like an ax, she advances through the meanderings of grief. When it comes to making choices, she has no doubts. She was so thorough. I was unable to be even a little bit sad. She took all the sadness. But I would have given her the sadness in any case. There was nothing left for me.

I tell her that I would like to be alone for a moment. A few minutes. The cold room was freezing. In those few minutes I put the nail in the pocket of Johannes’s gray suit. I did not want to look at him. His face is in my mind, in my eyes. I have no need to look at him. But I did the opposite. I looked at him rather well, to see, and to know, if there were signs of suffering. And this was a mistake. For, in looking at him so attentively, his face eluded me. I forgot his physiognomy, his real face, the usual one.

Miss Gerda has come to fetch me. I try to kiss Johannes on the brow. She recoils in sudden revulsion and stops me. It had been such a sudden desire this morning, to want Johannes’s ashes. Now it has vanished.

I did not know my father very well. One Easter holiday he took me with him on a cruise. The ship was moored in Venice. Her name was Proleterka. The Proletarian Lass. For years the occasion of our meetings had been a procession. We both took part. We paraded together through the streets of a city on a lake. He with his tricorne on his head. I in the Tracht, the traditional costume with the black bonnet trimmed in white lace. The black patent-leather shoes with the grosgrain buckles. The silk apron over the red of the costume, a red beneath which a dark bluish-purple lurked. And the bodice in damasked silk. In a square, atop a pyre of wood, they were burning an effigy. The Böögg. Men on horseback gallop in a circle around the fire. Drums roll. Standards are raised. They were bidding the winter farewell. To me it seemed like bidding farewell to something I had never had. I was drawn to the flames. It was a long time ago.

My father, Johannes H., was a member of a Guild, a Zunft. He joined it when he was a student. He had written a report called What the Guild Did and What It Could Have Done During the War. The Guild to which Johannes belonged was founded in 1336.

On the previous evening there had been the children’s ball. A big hall thronged with costumes and laughter. I was waiting for it all to be over. Perhaps Johannes was too. I do not like balls, and I wanted to take my costume off. The first time I took part in the procession (I had not yet started school) they put me in a sky-blue sedan chair. From the window, I waved at the other children who were watching the procession from the pavement. When the porters set me down on the ground, I opened the door and went off. I had not thought to run away. It was not rebellion, but pure instinct. A desire for the unknown. For hours I wandered through the city. Until I was exhausted. The police found me. And they handed me over to my lawful owner, Johannes. I was sorry. Given the circumstances, any chance of a more profound acquaintance between father and daughter was limited in the extreme. Observe and keep quiet. The two walk close to each other in the procession. They do not exchange a word. The father has trouble keeping in step with the march music. Two shadows, one moving slowly, with a visible effort. The other more restless. The people proceed in ranks of four. Beside them, a couple; the man in military uniform, the woman in costume. They are in step, their gait majestic, sanctified, proud. Heads held high. At night, sometimes, the burning effigy would return beneath closed eyelids. The roll of the drums even more martial, with a posthumous sound. In a hotel room, two days later, I left Johannes. The term of my visit had expired.

Proleterka had been chartered by some gentlemen who belonged to the same Guild as Johannes. The ones who paraded through the city in the month of April. They were to be our traveling companions. We set off, my father and I, by train for Venice. The carriage was empty. From that moment I would be with Johannes, my father. He is not yet seventy years old. White hair, parted, straight. Pale, gelid eyes. Unnatural. Like a fairy tale about ice. Wintry eyes. With a glimmer of romantic caprice. The irises of such a clear, faded green that they made you feel uneasy. It is almost as if they lack the consistency of a gaze. As if it were an anomaly, generations old. Johannes had a twin brother, with similar eyes. His brother’s eyes were often concealed by his eyelids. He would spend hours in the garden. In a wheelchair. He could manage to say: “Es ist kalt,” it’s cold. His tone held a blend of the awareness of a divine imposition and the mere earthly realization that cold is transitory. As was his illness. In those days they called it sleeping sickness.

In the compartment, Johannes is reading the newspaper. He reads for a long time. Perhaps he does not know what to say to me. I observe the fingers that hold the newspaper, and his shoes. I cast about for a topic of conversation. I do not find one. I think of the word Proleterka, the name of the Yugoslavian ship. There are more beautiful names for ships. Like the Indomitable, on which Billy Budd was hanged. Do you remember when the chaplain visits the sailor in irons in order to sow the idea of death in him? Billy Budd’s last words were: “God bless Captain Vere!” He blesses the man who ordered his execution. He blessed his executioner. I should like to talk to you of Billy Budd, instead of telling this brief story hoisted from the yard-arm, swaying before a headwind at the mercy of nothingness. Billy Budd, I see him as the landscape slips by, while the hours slip by in the company of Johannes. We do not know who Billy Budd’s father was, or where he was born. They found him in a pretty little basket lined with silk. I know Billy Budd much better than I know my father. “We’re here,” says Johannes. We have no luggage. It is on the ship. The Proleterka.

Father and daughter take the vaporetto to Piazza San Marco. The daughter looks farther and farther ahead; she wants to see the ship. Venice appears and disappears. They walk along the Riva degli Schiavoni. The daughter is impatient. Johannes walks slowly. He has a malformation of the foot. He wears shoes that are a bit high at the ankles.

I used to think that he was born that way. And that he had always had difficulty walking. But it had been caused by a carcinoma. I read this in an album, the traditional kind they give when a child is born. It records the first days of life, the first months, almost day by day. On the eighteenth month, Johannes notes that his daughter had gone to visit him in hospital. If she wants any information about his existence in the early years, all she has to do is leaf through the album. It is proof. It is the confirmation of an existence. Laconically, Johannes recorded what his daughter did, where they took her, her state of health. Brief phrases, without comment. Like answers to a questionnaire. There are no impressions, feelings. Life is simplified, almost as if it were not there. Johannes notes: his daughter has never cried. She has not been rebellious, she behaves correctly. A proper infancy. All is on the surface. About himself, Johannes, two personal notes. A minor heart attack and the carcinoma. When his daughter was two, notes Johannes, her grandfather (he writes the grandfather’s name and surname) died. At the cremation, many friends. His daughter shows herself to be nice and discovers everything. Johannes does not write “understands,” but “discovers.” So, the man observes his daughter. She must have been really well brought up and sweet, that little girl, about her grandfather’s death. Perhaps even then Johannes was thinking about his own death and hoped that the girl would be nice to everyone. That she would be nice to the world. To grief. When she was still small, she had to leave Johannes. Children lose interest in their parents when they are left. They are not sentimental. They are passionate and cold. In a certain sense some people abandon affections, sentiments, as if they were things. With determination, without sorrow. They become strangers. Sometimes enemies. They are no longer creatures that have been abandoned, but those who mentally beat a retreat. And they go away. Toward a gloomy, fantastic, and wretched world. Yet at times they feign happiness. Like funambulists, they practice. Parents are not necessary. Few things are necessary. Some children look after themselves. The heart, incorruptible crystal. They learn to pretend. And pretence becomes the most active, the realest part, alluring as dreams. It takes the place of what we think is real. Perhaps that is all there is to it, some children have the gift of detachment.

Father and daughter stand before the ship. She looks like a naval vessel. The red star glitters on the funnel. I look immediately at the lettering Proleterka. Blackened, patches of rust, forgotten. Sovereign lettering. The dusk is falling. The ship is large, she hides the sun that is about to sink into the water. She is darkness, pitch, and mystery. A privateer built like a fortress, she has survived stormy weather and shipwreck. We go up the gangplank. The officers are waiting for us. We are the last. Johannes has trouble getting up, and an officer helps him. They show us the cabin. Small. I would sleep there with Johannes. Two bunks, one above the other. I will have to sleep on top. The Proleterka puts out to sea at 1800 hours. She slips gently over the water. A raucous sound precedes our departure. A sound of farewell. There is no turning back. I look out of the porthole. I wonder how I shall manage to get out, to get into the sea, should I wish to slip away like Martin Eden.

I get changed. An hour’s time in the dining room. On the deck the passengers are looking at the sunset. They cannot miss it. Johannes is watching the sunset too. By now it illuminates nothing anymore. Darkness is come, the voyage has begun. The first sunset will be followed by others, for fourteen days. The Guild people are sure that they have organized everything in the best possible way. Even the weather. A sailor invites the ladies and gentlemen to go into the dining room. One after the other, almost in silence, the passengers in line. My father and I are again the last. We have a corner table. Johannes reads the menu, chooses the wine. He greets his friends, I greet them with a tight-lipped smile. Muggy heat. The ship sails on serenely. The crystal chandelier sways slightly. Like a leisurely pendulum, moved by inertia. Johannes is dressed in dark colors. Impeccable. We have barely exchanged a word. The ladies are in evening dress, a few grudging décolletés. In the room a continuous, slow, persistent swaying. A calm, malign rhythm, as if the waves of the sea were crooning a lullaby before stupefying the passengers. The chandelier swings a little more. It casts its light on the passengers and then leaves them in shadow, only to return faster. The room rises and falls. The flowers on the table move at irregular intervals. They slip away and then return to their place. Johannes distant, absent, elsewhere. Dessert, trifle. During dessert the force of the sea increases. I ask Johannes’s leave to get up. Outside, a raging wind. Shadows move frenetically. They are the sailors. I breathe in the sublime nocturnal solitude. The bad weather. And the danger. I do not think of Johannes. Of giving him my arm and helping him. Nothing matters at that moment.

I cannot keep my feet. After a few minutes a sailor grabs me and hurls me in front of my cabin. The crew had ordered all the passengers to remain in their cabins. They managed to finish the trifle.

The Proleterka has changed course. She is heading for Zara. A sailor, perhaps the same one who grabbed me, was seriously injured during the night. The following morning he was on a stretcher. I caress his face, I give his hand a squeeze. The stretcher is lowered onto a motor launch. I should like to leave the ship too. The captain salutes.