9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: And Other Stories

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

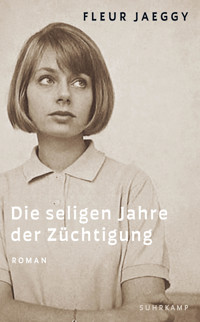

Set in postwar Switzerland, Fleur Jaeggy's eerily beautiful novel begins simply and innocently enough: "At fourteen I was a boarder in a school in the Appenzell". But there is nothing truly simple or innocent here. With the off-handed knowingness of a remorseless young Eve, the narrator describes life as a captive of the school and her designs to win the affections of the seemingly perfect new girl, Frederique. As she broods over her schemes as well as on the nature of control and madness, the novel gathers a suspended, unsettling energy.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 121

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

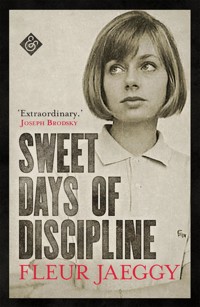

SWEET DAYS OF DISCIPLINE

Fleur Jaeggy

Translated by Tim Parks

Contents

SWEET DAYS OF DISCIPLINE

At fourteen I was a boarder in a school in the Appenzell. This was the area where Robert Walser used to take his many walks when he was in the mental hospital in Herisau, not far from our college. He died in the snow. Photographs show his footprints and the position of his body in the snow. We didn’t know the writer. And nor did our literature teacher. Sometimes I think it might be nice to die like that, after a walk, to let yourself drop into a natural grave in the snows of the Appenzell, after almost thirty years of mental hospital, in Herisau. It really is a shame we didn’t know of Walser’s existence, we would have picked a flower for him. Even Kant, shortly before his death, was moved when a woman he didn’t know offered him a rose. You can’t help but take walks in the Appenzell. If you look at the small white-framed windows and the busy, fiery flowers on the sills, you get this sense of tropical stagnation, a thwarted luxuriance, you have the feeling that inside something serenely gloomy and a little sick is going on. It’s an Arcadia of sickness. Inside, it seems, in the brightness in there, is the peace and perfection of death, a rejoicing of whitewash and flowers. Outside the windows, the landscape beckons; it isn’t a mirage, it’s a Zwang, as we used to say in school, a duty.

I was studying French, German and general culture. I wasn’t studying at all. The only thing I remember of French literature is Baudelaire. Every morning I got up at five to go out and walk. I climbed high up the hill and saw a strip of water on the other side, down at the bottom. Lake Constance. I looked at the horizon, and at the lake; I didn’t realise as yet that another school awaited me by that lake. I ate an apple and walked. I was looking for solitude, and perhaps the absolute. But I envied the world.

It happened one day at lunch. We had all sat down. A girl arrived, a new one. She was fifteen, she had hair straight and shiny as blades and stern staring shadowy eyes. Her nose was aquiline, her teeth when she laughed, and she didn’t often laugh, were sharp. She had a fine, high forehead, the kind of forehead that makes thought tangible, a forehead past generations had endowed with talent, intelligence and charm. She spoke to no one. Her looks were those of an idol, disdainful. Perhaps that was why I wanted to conquer her. She had no humanity. She even seemed repulsed by us all. The first thing I thought was: she had been further than I had. When we rose from the table, I went up to her and said: ‘Bonjour.’ Her Bonjour was brusque. I introduced myself, name and surname, like a recruit, and when she had told me hers it seemed the conversation was over. She left me there in the dining hall, amongst the other chattering girls. A Spanish girl told me something in an excited voice, but I paid no attention. I heard a clamour of different languages. That whole day the new arrival didn’t show her face, but in the evening she appeared punctually for dinner, tall behind her chair. Standing still, it was as if she were veiled. At a nod from the headmistress we all sat down and after a few moments’ silence everyone was talking again. The following day it was she greeted me first.

In our lives at school, each of us, if we had a little vanity, would establish a façade, a kind of double life, affect a way of speaking, walking, looking. When I saw her writing I couldn’t believe it. We almost all had the same kind of handwriting, uncertain, childish, with round, wide ‘o’s. Hers was completely affected. (Twenty years later I saw something similar in a dedication Pierre Jean Jouve had written on a copy of Kyrie.) Of course I pretended not to be surprised, I barely glanced at it. But secretly I practised. And I still write like Frédérique today, and people tell me I have beautiful, interesting handwriting. They don’t know how hard I worked at it. In those days I didn’t work at all, and I never worked at school, because I didn’t want to. I cut out reproductions of the German expressionists and crime stories from the papers and pasted them in an exercise book. I led her to believe I was interested in art. As a result Frédérique granted me the honour of accompanying her along the corridors and on her walks. At school – though I think it goes without saying – she was top in everything. She already knew everything, from the generations that came before her. She had something the others didn’t have; all I could do was justify her talent as a gift passed on from the dead. You only had to hear her reciting the French poets in class to realise that they had come down to her, were reincarnated in her. We, perhaps, were still innocent. And perhaps innocence has something crude, pedantic and affected about it, as if we were all dressed in plus fours and long socks.

We came from all over the world, lots of Americans and Dutch. One girl was coloured, as they say today, a little black girl, curly-haired, a doll for us to admire in the Appenzell. She had arrived one day with her father. He was President of an African state. One girl of every nationality was chosen to form a fan shape at the entrance to the Bausler Institute There was a redhead, a Belgian, a Swedish blonde, the Italian girl, the girl from Boston. They all cheered the President, lined up with their flags in their hands, and they truly did represent the world. I was in the third row, the last, next to Frédérique, the hood of my duffel coat pulled over my head. In front – and if the President had had a bow, his arrow would have pierced her heart – stood the headmistress of the school, Frau Hofstetter, tall, heavily built, very dignified, a smile buried in her fat cheeks. Next to her was her husband, Herr Hofstetter, a thin, small, shy man. They raised the Swiss flag. The little black girl took the leading position in the formation. It was cold. She was wearing a dark-blue, bell-shaped coat, a lighter-blue velvet collar. I must confess that the black President cut a good figure at the Bausler Institut. The African head of state trusted the Hofstetter family. There were one or two Swiss girls who weren’t impressed by the pomp with which the President had been received. They said all fathers should be treated as equals. There are always a few subversives tucked away in a boarding school. The first signs of their political thinking emerge, or of what you might call a general vision of the whole. Frédérique had a Swiss flag in her hand and looked as though she were holding a pole. The youngest girl curtsied and offered a bunch of wild flowers. I don’t remember if the black girl ever managed to make friends with anybody. We often saw the headmistress holding her hand and taking her for walks. Yes, Frau Hofstetter in person. Maybe she was afraid we would eat the girl. Or that she wouldn’t stay pure. She never played tennis.

Frédérique became more and more distant every day. Sometimes I would go to see her in her room. I slept in another house, she was with the older girls. Although there were only a few months between us, I had to stay with the younger girls. I shared my room with a German whose name I’ve forgotten, she was so uninteresting. She gave me a book on the German expressionists. Frédérique’s cupboard was incredibly tidy, I didn’t know how to fold pullovers so that not so much as a centimetre was out of place and I had a low mark for tidiness. I learnt from her. Sleeping in separate houses it was as if there were a generation between us. One day I found a little love note in my pigeon hole, it was from a ten-year-old who begged me to let her become my favourite, to make a pair. Impulsively I answered with an unfriendly no, and I still regret it today. I regretted it then too, immediately, no sooner than I’d told her that I had no use for a sister, that I wasn’t interested in looking after a little favourite. I was getting to be unpleasant because Frédérique was eluding me and I had to conquer her, because it would be too humiliating to lose. I only took a look at the younger girl when it was too late and I had already offended her. She was really pretty, very attractive, and I had lost a slave, without getting any pleasure out of it.

The younger girl never spoke to me again from that day on, nor even said hello. As you see, I had yet to learn the art of compromise, I still thought that to get something you had to go straight for your goal, whereas it is only distractions, uncertainty, distance that bring us closer to our targets, and then it is the target which strikes us. Yet I did have a strategy with Frédérique. I had a reasonable amount of experience of boarding school life. I’d been a boarder since I was eight years old. And it’s in the dormitories that you get to know your fellow boarders, by the washbasins, at break time. My first boarding school bed was surrounded by white curtains, and covered with a white piqué bedspread. Even the dresser was white. A pretend room, followed by twelve others. A sort of chaste promiscuity. You could hear the sighs. My room-mate in the Bausler Institut was a German, well-behaved and mean the way stupid girls often can be. In bright white underwear her body was quite attractive, shapely almost, but if by accident I were to touch her I had a feeling of repugnance. Maybe that’s why I got up so early in the morning for my walks. By eleven, during the lessons, I would start feeling sleepy. I looked over to the window, and the window returned my expression and had me dozing off.

Frédérique and I not only slept in different houses at night, we were also in different classrooms during the day. We didn’t sit close to each other at table, but I could see her. And at last she began to look at me. Maybe I was interesting too. I liked German expressionism and the thought of the life, the crimes I hadn’t yet experienced. I told her that at ten I had insulted a mother superior by calling her a cow. What a simple word, I was ashamed of my simplicity when I told her about it. I was expelled from the convent school. ‘Beg pardon,’ they said. I wouldn’t. Frédérique laughed. She was kind enough to ask me why I’d done it. And gradually I began to talk about myself at eight years old. At the time I used to play football with the boys, then they sent me to that dismal college. At the end of a dismal corridor was a chapel. To the left a door. Inside, a mother superior, ethereal, delicate, who took me under her wing. She caressed me with her slender, soft hands, she sat next to me as if I were a friend. One day she disappeared. In her place arrived a buxom Swiss from Canton Uri. It’s common knowledge that a new leader will hate the predecessors’ favourites. A boarding school is like a harem.

Frédérique told me I was an aesthete. It was a new word for me, but it immediately made sense. Her handwriting was an aesthete’s handwriting, that much I appreciated. Likewise her scorn for everything was an aesthete’s scorn. Frédérique hid her scorn behind obedience and discipline; she was respectful. I hadn’t as yet learnt to dissemble. I was respectful with the headmistress, Frau Hofstetter, because I was afraid of her. I was ready to curtsey to her. Frédérique never needed to curtsey, because her way of respecting others instilled respect. And I noticed this. Once, perhaps to distract myself from my pursuit of Frédérique, I accepted a date with a boy from a nearby boarding school, the Rosenberg. It was a short date. They saw me. Frau Hofstetter called me to her office. She was broad as a cupboard in a blue tailleur, white blouse, a brooch. She threatened me. I told her he was just a relative. It was true, in fact his mother had written to Frau Hofstetter on purpose to tell her to be careful that I didn’t go to see him. I pretended to cry. She was touched. Where had all the strength I’d had at eight gone, the confidence, the self-control? At eight I hadn’t given a moment’s thought to any of the other girls. They were all the same, all detestable and mean. Even now, I can’t bring myself to say I was in love with Frédérique, it’s such an easy thing to say.

That day I was afraid they would throw me out. One morning, breakfasts were delicious, I dunked my bread in my coffee. Having slapped my dunking hand, the headmistress made me stand up. At eight I would have picked up my cup and tossed it in her face. Who gave her the right to insult me? Frédérique ate with her elbows pressed against her bust. Never did an elbow of Frédérique’s touch the table. Did she scorn her food too? She was so perfect. When we went for walks together, every day now, the two of us alone, sometimes she would walk in front of me and I would watch her. Everything about her was right, harmonious. Sometimes she put her hand on my shoulder and it was as though it must stay like that forever, through the woods, the mountains, the paths, uneamitiéamoureuse