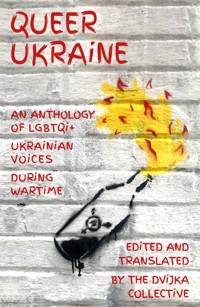

Queer Ukraine E-Book

6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Renard Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Against the backdrop of brutal invasion, it is much easier for right-wing figures to target marginalised groups, and during wartime the queer community is exceedingly vulnerable to persecution, scapegoating and censorship. Being visibly queer in Ukraine is an act of rebellion in itself, but LGBTQI+ people find ways to express themselves against all odds, to create beyond all constraints. And what is queerness without defiance – the linking of arms, the echo of a hundred voices? Every voice tells a story, and this anthology is a platform for these voices, an archive of their existence. It is time for them to tell their stories on their own terms – and for the rest of the world to stand in solidarity with them. Proceeds from the sales of this book go to a selection of charities supporting LGBTQI+ people in Ukraine. The list is periodically reviewed so that funds go to where they're most sorely needed, but includes: TU Platform Mariupol (Supporting queer youth), Queers For Ukraine (Supporting people with HIV in Ukraine and delivering much-needed hormones for the trans community) and Insight NGO (Humanitarian Aid for the LGBTQI+ community in Ukraine).

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 107

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Queer Ukraine

An Anthology of Lgbtqi+ Ukrainian Voices During Wartime

edited and translated by DViJKA

renard press

Renard Press Ltd

124 City Road

London EC1V 2NX

United Kingdom

020 8050 2928

www.renardpress.com

Queer Ukraine first published by Renard Press Ltd in 2023

‘Ukrainian Queerness’ first published on MaksymEristavi.com in 2022

‘Transness in Traditional Ukrainian Culture’ first published in Ukrainian as ‘Transhendernist’ u tradytsijnij kul’turi Ukrajiny’ on update.com.ua in 2021

Text © the Authors, 2023

Translated by DViJKA

All photographs and inside illustration © Rebel Queers, 2023

Design by Will Dady

The authors assert their right to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All URLs accessed 1st January 2023. Renard Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of third-party websites referenced, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is accurate or appropriate.

Renard Press is proud to be a climate positive publisher, removing more carbon from the air than we emit and planting a small forest. For more information see renardpress.com/eco.

All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced, used to train artificial intelligence systems or models, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior permission of the publisher.

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe – Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia, [email protected].

Contents

Foreword

From the Editors

Queer Ukraine

maksym eristavi

marichka

yana lys (lyshka)

goodvampire

alsu gara

ernest huk

oleksandr bosivski

tanya g

elliott miskovicz

taras gembik

dimettra

t

Foreword

What do you think of when you think of queerness? Is it rainbow flags and parades, glitter and joy? Is it a corporate, sanitised version of pride, where you can only be seen if you’re deemed worthy of a spotlight? Is it heart-warming coming-out stories? Is it the latest legal recognition of LGBTQI+ people’s fundamental liberties?

In Ukraine, being queer is far from easy. But what is queerness if not resistance? What is queerness if not defiance? What is queerness if not the linking of arms, the echo of a hundred voices? For every voice tells a story, and every story is a thread in the grand tapestry of our existence.

Ukraine, where finding a community means salvation. Where being visibly queer is an act of rebellion. Where underground nightclubs become a bastion of solidarity. Where LGBTQI+ artists find ways to express themselves against all odds, to create beyond all constraints. Ukraine, our homeland; our beautiful, beautiful country. We’ve always been a part of you, and we’ll always keep fighting for your freedom – no matter if our fight is twice as hard.

Ukraine, this is a love letter to you.

From the Editors

Both historically and in modern times queerness in Ukraine has meant resistance. Resistance to direct queerphobicrepression and condemnation from the metropole. Resistance to its gruesome after-effects, on both a collective and individual level, on the (post)colony. Resistance against the erasure of your whole being.

If history has shown us anything, it’s that during wartime, queer people are exceedingly vulnerable to persecution, scapegoating and censorship. Against the backdrop of a brutal invasion, it is much easier for conservative groups to target marginalised communities and paint them as the enemy, as a hindrance to the development of a country, completely disregarding the rich history of the LGBTQI+ community on Ukrainian soil, which stretches back to antiquity. Our enduring contributions to cultural growth and our commitment to fighting for liberation cannot be ignored.

Recent years have seen the emergence of Ukrainian Queer theory, and we urge readers to get hold of Anton Shebetko’s A Very Brief and Subjective Queer History of Ukraine and Nataliya Gurba’s Queer Joy, Ukrainian Liberation. Much like anywhere else, the LGBTQI+ community in Ukraine is far from being a homogeneous entity, and engaging with a vast array of diverse perspectives is vital for developing a nuanced understanding of our past and present.

This anthology is not only a platform for sharing our experiences, it is an archive of our existence and a testament to our permanence. We hope it will contribute to the visibility of queer Ukrainians and inspire more works like it to be produced in the coming years. It’s time for us to tell our stories on our own terms – and for you, dear reader, to listen and stand in solidarity with us.

– DViJKA

About DViJKA and Rebel Queers

The DViJKA collective consists of a Kyiv-born, London-based duo of artist-researchers working in the fields of performance, film, writing and archiving. Their work revolves around spotlighting the experiences of LGBTQI+ Ukrainians and documenting the history of queerness on their land.

Rebel Queers is a group of queer activists who work to reclaim their right to the city of Kyiv. Their protests do not define themselves as being against anything, but rather honouring queer people and realising their liberation. Their actions are conscious of transphobia and queerphobia, and how they intersect with other forms of oppression.

queer ukraine

An Anthology of Lgbtqi+ Ukrainian Voices During Wartime

maksym eristavi

Ukrainian Queerness

Before drafting this essay, I chatted with a passionate western volunteer who has been helping Ukrainians. The person was frustrated that their family wouldn’t understand or share their enthusiasm, but said that finding support within the ‘chosen family’ of Ukrainians is uplifting.

As a queer Ukrainian, I cannot relate more to the ‘chosen family’ experience – it is remarkable how this sentiment has become part of the anti-colonial solidarity around Ukraine. It is no coincidence – it was easier for me to come out as queer than as Ukrainian – but after I did both, only then did the queerness of being Ukrainian become so apparent.

The resistance of it: the resistance to the attempts to erase your identity, gaslight, dehumanise, exploit and dominate you.

The survival of it: forging community links in your darkest hour, nurturing the sense of collective care and responsibility for each other, and reclaiming the language and culture codes that were used to oppress you.

The love of it: harbouring faith and hope despite facing the most unspeakable evil humanity is capable of; dreaming and envisioning a world that is more just; preserving devotion to the idea of equality and freedom and liberty; relentlessly trying to reject hate; not losing your ability to love.

These qualities are not only quintessentially queer, but also very anti-colonial.

I want to take a moment during the genocide that my people are enduring to reflect on the colonial nature of homophobia under Russian colonial rule, the everyday manifestation of it, and how the Ukrainian decolonisation struggle is fundamentally queer, because I am sure it is integral to understanding today’s Ukrainians’ fight, too.

If you knew me as a kid, you would not be surprised to learn that I was more ashamed of coming across as Ukrainian than as gay. I was bullied for my queerness and femininity; but my father’s very Ukrainian surname and my Ukrainian accent got me into much more trouble, and I started using my mother’s maiden name as an alias.

Growing up in Eastern Ukraine in the 1990s, homophobia was part of my everyday experience, but I’d say this was less a conscious choice to dehumanise and oppress people, and more a lack of education. Moreover, back then, queer acceptance was on the rise across former Russian colonies in Eastern Europe. Belarus1 and Moldova2 hosted their first pride marches in 1999 and 2002 respectively – way ahead of some eastern EU States. Public displays of queerness in pop culture was growing. I might have been called homophobic names in school, but they would always have something to do with the names of prominent queer celebrities of the time.

Things started to roll back in the late 2000s when Russia got its colonial shit together and made the articulated ideology of homophobia part of its neighbourhood foreign policy in the renewed push for colonial domination. This is when Moscow integrated homophobia into a coherent ‘civilisation ideology’ of Russkiy Mir3 and provided their neighbourhood proxies with rigorous and appealing talking points about why homophobia (and the repression of women or anything progressive or indigenous) is a superior worldview.4 The concept that sexual or gender diversity is an ‘alien Western concept’ is now a strengthening ideology binding millions from Russia to the US and from Brazil to Uganda. It has its roots in the Russian disinformation campaigns5 of the late 2000s, with the ‘Gayrope’ concept portraying homosexuality as a Western conspiracy to undermine Vladimir Putin as a self-proclaimed defender of conservative moral values. The narrative is designed to help Putin to justify neocolonial expansion into neighbouring countries and to preserve regional kleptocracies under the facade of protecting ‘a civilisational block’. One of the most prominent features was the export of Russian ‘gay propaganda’ laws,6 the adoption of which would be a must to secure financial and political backing from the metropole.

Luckily for queer Ukrainians like me, almost two dozen attempts to pass similar laws in Ukraine all failed. It was no coincidence that they were all initiated and backed by pro-Russian political forces: since the early 2010s institutionalised homophobia quickly became synonymous with the resurgent Russian colonial influence in Ukraine and beyond. You can map pro-Russian political agents in the region7 by their support for the criminalisation of queerness, even if they would be cautious about publicly identifying as pro-Russian.

I would never have connected the dots between my queerness, my Ukrainianness and Russian colonialism so obviously until something happened to me personally. For almost a year in the early 2010s, I lived in Moscow. It remains the most degrading and revolting experience of my life. I faced virulent homophobia for being openly queer; I faced rabid xenophobia for being Ukrainian; and I faced nasty racism for being mixed-race. I could never tell what it was that provoked specific slurs from random people in the street or micro-aggression at work: my femininity, my Georgian nose, my Asian eyelid fold, my dark Roma hair or my Ukrainian accent. It was too much queerness for folks at the heart of a patriarchal colonial empire to handle.

The coloniality of attempts to criminalise queerness is, of course, not new; it is just the Russian chapter in this history that is rarely acknowledged. As my co-authors and I explain in Untapped Power,8 a book about decolonising our foreign policies to promote more diversity, most laws still existing in former colonies worldwide were first introduced by colonisers.9 For example, the British colonial empire left a vast trail of anti-sodomy laws in its wake.10 Russian colonialism was no different: absolutely all anti-homosexualitylegislation in former Russian colonies was written in Moscow. To date, the only two surviving laws criminalising homosexuality in the Russian neighbourhood, in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan, were introduced by the Russian colonial administration in the nineteenth century, and were updated in 1926 during the Soviet colonial occupation.

Like other Russian colonies, formal attempts to criminalise, marginalise or erase Ukrainian queerness all trace back to times of Russian rule. Traditionally matriarchal, Ukrainian society was historically more comfortable with expressions of femininity, sexual and gender diversity. Long before Russia existed as a unified State, Ukrainian letopises of the Kievan Rus’ were freely documenting and glorifying stories of same-sex affection and love.11

Take the eleventh-century story of princelings Borys and Gleb,12 which also documents a deep and possibly romantic affection between Borys and a male friend. Centuries later, Russian colonial rule started systemically erasing any traces of Ukrainian diversity and queerness. That’s how, for example, a strict celibacy rule covering any type of sexual acts at military posts of Ukrainian Cossacks turned into a Moscow-pushed myth of an exclusive ban on gay sex by the founders of the first Ukrainian democracy of the seventeenth century (the same historical distortion was also used to erase the prominent role of Ukrainian women during the Cossack era).13

Or take the unapologetic and anti-colonial queerness of the Ukrainian literary geniuses Lesya Ukrainka14 and Taras Shevchenko.15 Queerness so strong that it still speaks powerfully to Ukrainians generations down the line. ‘There’s the power in her way of naming herself,’ writes Nataliya Gurba in their series of powerful essays16 on the nexus of queer jo