Contents

Also by Jan Newton

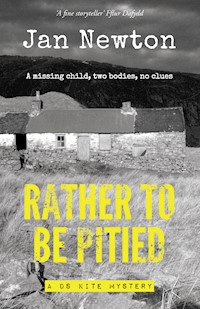

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE

CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX

CHAPTER THIRTY-SEVEN

CHAPTER THIRTY-EIGHT

CHAPTER THIRTY-NINE

CHAPTER FORTY

CHAPTER FORTY-ONE

Quote

About Honno

Copyright

Also by Jan Newton and available from Honno Press

DS Kite novels

Remember No More

Rather to be Pitied

by

Jan Newton

Honno Modern Fiction

For Merv, always

As always, there are so many people who have encouraged me in the writing of this book. I have been gratified and humbled by the response toRemember No More, the first book in the Julie Kite series, which made it so much easier to embark on this, the second. The wonderful people of mid Wales and beyond have taken Julie Kite to their hearts, and I’m truly grateful for their continued support and feedback.

Grateful thanks to Chris Kinsey, who motivates me constantly, to write and to improve.

To Kevin Robinson, retired West Yorkshire Police Inspector, once again huge thanks for his support in ensuring that my facts were factual, and for painstaking proof reading with a forensic eye. As usual, any mistakes in any aspect of this novel are, of course, my own.

Thanks to everyone at Honno for their help and support, especially Caroline Oakley, my editor, for accommodating all the recent ups and downs away from the writing side of life.

Lastly, but most importantly of all, my gratitude to Mervyn, without whom none of this would have been possible. For over thirty years, he has supported everything I have ever wanted to do with insight, patience and pride. I will always be grateful.

CHAPTER ONE

Day One

Mark Robinson sat down on a dry tussock of grass in the shelter of a slab of rock. If it hadn’t been for the breeze, this would have been a perfect July day. There was barely a cloud in the china-blue sky and from somewhere nearby, the cry of a curlew stirred long-forgotten memories of his own childhood. One more hour and he could finally drop the kids off at the school gates and head for home.

Mark sighed. He’d always prided himself on his patience, on the fact that he would always take the time to listen to his pupils and would never ever give up on them, no matter how trying they were. And yet, after three days under canvas with this lot, traipsing around in circles in the middle of nowhere, he was beginning to appreciate the attitudes of some of his battle-weary colleagues. He counted his charges yet again. God knows what would happen to them when they did the expedition on their own in three weeks’ time. He pushed his water bottle back into his rucksack and stood up.

‘Right, where is he?’

‘Who, Sir?’

‘Very funny, David, as if we couldn’t guess who might be missing.’ Mark clambered onto the rock he had been sitting on and scanned the moorland. ‘Where is he this time?’

‘I’ve got him, Sir. Look, he’s over there by that sheep.’

‘Could you be a bit more specific in the sheep department, Sasha, help to pinpoint it a little.’

‘The dead one, Sir, there.’

Mark looked to where the girl was pointing. Three hundred yards away, Owen Lloyd was approaching the carcass of a black sheep with unaccustomed alacrity. Entirely appropriate. As they watched, the boy suddenly took a step backwards, then another, still staring at the sheep, before turning back towards the group and breaking into a run. Mark watched him stumble over the clumps of reed and the tufts of tough moorland grass, but it wasn’t until the boy stopped suddenly and bent forward with his hands on his knees that Mark set off towards where Owen was stooped.

‘Stay there,’ he shouted over his shoulder. ‘Sasha, you’re in charge of keeping everyone here, OK? Don’t let them move.’

By the time Mark reached him, Owen was retching up his packed lunch into the peat.

‘What is it? What’s the matter?’

Owen wiped his mouth on his sleeve and pointed in the direction of the sheep. ‘Over there, Sir.’

‘It’s all right, it’s just a dead sheep. I know it’s sad, but it happens all the time out here. It’s difficult to get to. It’s hard for the farmers to cover such a vast, boggy area.’

Owen shook his head and stared at his teacher. His eyes looked huge and dark in his pale face and Mark realised, perhaps for the first time, that Owen Lloyd was still just a child.

‘It’s not a sheep, Sir.’ Owen’s bottom lip trembled and he closed his eyes.

‘Stay here,’ said Mark. ‘I’ll go and have a look.’

‘Don’t, Sir, it’s horrible.’

‘You stay here. I’ll go and check it out, it might just be injured.’

‘It’s a body, Sir,’ Owen blurted, ‘and it’s covered in maggots.’

Owen Lloyd’s description was all too accurate. The skin on the man’s face was dark and peeling. Flies buzzed lazily around him. Mark tried to look away. The smell caught in his throat like the sickly-sweet whiff of something decomposing gently in the bottom of a hedgerow, but far, far worse. He stood up and struggled to swallow the bile that burnt his throat. Against his better judgement, he glanced back at the corpse. One of the man’s hands appeared to be missing; the cuff of his black denim jacket rested in the mud and several fingers, a couple of small bones and a gold ring lay scattered next to him. The bones could have been sheep bones, couldn’t they? But the ragged flesh which covered some of them looked far too human. Sheep didn’t bite their fingernails either, did they? His stomach lurched. He lifted his phone from his pocket. No signal. He backed away as if retreating from something sacred, then turned, took a deep breath and returned swiftly to where Owen was sitting with his head in his hands on a clump of grass.

‘Have you got your phone on you, Lloydy?’ he asked, as casually as he could.

The boy looked up at him. ‘But you said we couldn’t bring phones, Sir.’

‘And we both know that would make no difference at all, don’t we?’ Mark forced a grin. ‘Could you check to see whether you’ve got a signal?’

‘Honest, Sir, I haven’t got my phone.’

‘OK.’ Mark took him gently by the elbow and led him back towards where Sasha was standing high on the rock, hands on hips, attempting to keep the group in order. ‘Listen, Owen, I’d appreciate it if you didn’t tell them what you saw. There’s no need for them to have nightmares too, is there?’

Owen nodded. ‘Do you think… well, could he have been murdered, Sir?’

‘Out here?’ Mark shrugged. ‘There’s not much chance of that is there? It’s far more likely that he was out walking and was taken ill, I’d have thought. Anyway,’ he put his hand on the boy’s shoulder, ‘let’s not worry about that now shall we, let’s just get you all to the minibus.’

‘What is it, Lloydy?’ David was running out to meet them. ‘You all right?’

‘Yep, I’m fine.’ Despite the wobble in his voice, Owen managed a nonchalant shrug. He looked up at Mark. ‘It was just a sheep.’

CHAPTER TWO

Day One

Julie Kite watched DI Craig Swift scuttle across the office towards her. He only ever moved as quickly as this when there was something really important to impart. She was already reaching for her jacket when he approached her desk.

‘A group of school kids have found a body,’ he said, slightly breathless from his exertions.

‘Where?’

‘Above Pont ar Elan, on the Monks’ Trod.’

Julie frowned. ‘On the what?’

‘Follow me, I’ll fill you in on the way.’

She smiled. So much for him being office-based these days. Rhys Williams rolled his eyes as she passed his desk. One of these days, Swift would let the two of them out together without him. Julie followed Swift down the stairs and through the reception area. Brian Hughes, the desk sergeant, grinned at her as she whizzed past him in an attempt to keep up with Swift. It was amazing how quickly he could shift if he wanted to.

Swift strode across the car park, dropped into the driver’s seat of his Volvo, waited for Julie to clamber in and fasten her seatbelt and crunched the gear lever into reverse.

‘Right, so where are we headed, Sir?’

‘Pont ar Elan. Bridge on the River Elan.’

‘And that’s where, exactly?’

‘It’s up above Rhayader on the old Aberystwyth Road.’ Swift steered the nose of the car out of the car park and into the school traffic – the only sort of rush hour Julie had encountered since her move from Manchester Metropolitan Police, three months before. She smiled to herself as she watched drivers politely giving way to each other at a tricky junction, as they did every day.

‘So, what’s this Trod thing all about then?’

‘The Monks’ Trod,’ said Swift. ‘That’s one for your Adam. He probably knows more about it than I do already.’ He swerved round a campervan which had stopped suddenly. Its occupants appeared to be arguing over a map.

‘It’s an ancient route up in the hills.’ He nodded towards the north. ‘Apparently the monks used to use it to travel from Strata Florida Abbey in Pontrhydfendigaid to the sister house at Abbeycwmhir.’

Julie blew out her cheeks. She would never manage these Welsh names with their convoluted vowels. ‘Yeah, he’s already mentioned something about drovers’ roads. Would that be similar?’

Swift laughed. ‘He doesn’t hang around does he now? How’s he getting on at the High School? Has he settled into the new job by now?’

‘Oh God, he loves it, and the kids, the countryside, the lack of traffic, having no neighbours, the whole bit. It’s as though he was always meant to be here. He’s got huge plans for the summer holidays.’ She grimaced. ‘But almost all of them involve running and cycling.’ She turned to Swift. ‘I don’t suppose you know of anywhere he could practise his open water swimming, do you?

Swift glanced at her. ‘Do I look as though I would have the inclination or the ability to squash myself into a wetsuit, Sergeant?

Julie stifled a smile. ‘Maybe you have a point there, Sir.’

Swift slowed to allow an oncoming lorry to squeeze past and then he accelerated away round the tight bend, bringing the solid stone walls of the cathedral into view on their right. ‘Strangely enough, I can’t say I’ve ever heard of anyone wanting to do open water swimming.’

‘What about up at the reservoirs, Sir?’

‘The Elan Valley?’ Swift shook his head. ‘No swimming, sailing or otherwise larking about up there. Not on the water anyway.’

‘Oh well, it was worth a try.’

‘And what about you, Julie? Are you feeling a bit more settled here now?’

Julie watched through the side window as the houses petered out and the car headed into open countryside. ‘I’m getting there, Sir. I love the way everybody knows everyone else and the fact that it’s completely silent at night. I love the views and the rivers and the way people calculate journeys in minutes rather than miles.’ She thought of home, of the centre of Manchester, the bustle and drive of the place, the fact that everyone was a comedian. ‘I’m a townie at heart though. I think it may take a little while longer for me to feel like a total country bump– er, person, Sir.’ She gazed over fields full of sheep and ever-growing lambs. It was a very long way from the concrete and tarmac maze she had been used to. ‘Would I be right in thinking that this location’s going to be muddy, wet and covered in sheep shit?’

‘See, you’ve cracked it. Spoken like a true local that was. I don’t suppose you remembered to bring your wellies?’

‘Actually, Sir, I didn’t. Give me time, it’s not quite a reflex reaction yet.’

Swift laughed. ‘You’re in luck, Sergeant. Apparently this one’s not too far off the road.’

*

Dr Kay Greenhalgh’s black Alfa Romeo was in the tiny car park at Pont ar Elan. Next to it was a marked patrol car and a gleaming black van with chillingly dark tinted windows. Swift slid the Volvo to a halt. Just up the lane, a white Mountain Rescue Land Rover was tucked into the bank, from which a pair of deep and grass-filled vehicle tracks led sharply uphill.

‘Who found the body?’ Julie asked, as Swift pulled on a pair of battered black wellingtons. He slammed the boot lid, hitched up his suit trousers and set off up the lane towards the Land Rover.

‘It was a school kid on a practice run for a Duke of Edinburgh expedition.’

‘Kids? Out here on their own?’

‘They had a teacher with them, thank God. He phoned it in from the bus, but he insisted on taking them back to school once he knew we were on our way. They had parents waiting to collect them, so he thought it would be better to get them out of the way. He said he didn’t want them to see anything they shouldn’t.’ Swift’s breathing became more laboured with the gradient of the hill and he waved Julie past him as they drew level with the Land Rover. ‘Up that slope and turn right at the top.’

Julie followed the line of the track as it disappeared round the curve of the hill. Away to her left, the river Elan bent left and right then broadened into the beginnings of what looked like a lake. Bog cotton waved in the breeze, the white heads reminding her of enthusiastic and exhausting trips to Hayfield and Edale with Adam. At the top, she waited for him to catch her up.

‘It’s a godforsaken spot, Sir. He probably died of hypothermia.’

‘In July, Sergeant?’

Julie laughed. ‘It’s July, Sir, but it feels like February in Urmston.’ Despite the heat of the sun, the wind felt as though it came straight from the Arctic. Overhead, a buzzard circled and she shivered. ‘Do we know who he is?’

‘Not yet, but no doubt the good doctor will have a theory.’

Despite Swift’s assurances, Kay Greenhalgh was a good ten-minute muddy walk from the road. As they climbed over the brow of a rock-strewn bank, they saw her and her entourage of Scene of Crime Officers, starkly obvious against the unrelenting greens and browns of moorland, in their light blue paper suits. Outside the locus, there were two uniformed PCs, and two men dressed in black who stood motionless, their hands clasped and heads slightly bowed. Four members of the Mountain Rescue team, in their bright orange suits and white helmets, waited on the other side of the cordoned-off rectangle, with a sled-like stretcher on the ground between them. The scene beneath her reminded Julie of watching a play from the front circle, with the brightly coloured costumes of the actors brilliantly lit in the dark theatre. This production needed no words.

Julie squelched on down the track through puddles with their iridescent surface indicative of peat. She attempted to wipe the worst of the mud from her shoes on a tussock of reeds. ‘I thought you said it wasn’t far off the road, Sir.’

‘It could have been worse, Julie, this track goes on for miles.’

The doctor greeted Swift with her stock opening line. ‘Good afternoon, Inspector. Nice of you to join us.’ Kay Greenhalgh smiled at Swift. ‘I’ve almost finished here. I need to get him on the slab before I’ll be able to tell you anything useful. It looks as though he’s been dead for five or six days at most, judging by the maggot activity. There’s no rigor and apart from the head, the skin has a marked green tinge. He also has a catastrophic head injury, but that’s all I can say for now.’

The bloodstains on the rock showed that the man had probably been in a sitting position originally, with his back leaning against the rock and his legs straight out in front of him. Now he was slumped forward into a dark tidy heap. Dr Greenhalgh lifted the shoulders. The skin on his face was dark – almost black – and there were maggots weaving their way in and out of every facial orifice.

‘Why is the skin on the face at a different stage of decomposition to the rest of him?’ Julie asked.

‘Well observed, Sergeant. Unfortunately, I have absolutely no idea. I’ll know more once I’ve done some testing.’

‘This is probably a daft question, but do you think he could have been a rambler?’ Julie asked.

‘It’s not a daft question. In my experience, there are very few daft questions. He was wearing boots and they were fairly old ones by the looks of the sole pattern, though he didn’t have a rucksack.’

Greenhalgh leaned back and took a long look at the body. A frown flitted across her face. ‘He didn’t have a map or satnav either. Would you walk out here without bringing anything with you?’

‘Did the head injury kill him do you think, or could he just have fallen and then been caught out by the weather?’ Swift leaned over the blue and white incident tape to get a closer look at the face and grimaced.

Greenhalgh gently released the shoulders. ‘He could have died of exposure of course, but it’s unlikely at this time of year, even up here.’ She turned to gather up a sheaf of evidence bags. ‘And I’m not even sure yet that he died in situ. Those boots are a pretty common make but there are a surprisingly large number of other types of boot print on the ground for such a godforsaken spot.’ Kay stepped under the tape. ‘Although I’d not fancy carrying a body so far from the road, even one this slight.’ She crouched suddenly, beside her bag, and looked at the corpse from her new location. She shook her head, filed the evidence bags and snapped her briefcase shut.

‘Could he have been dumped from a vehicle?’ asked Julie.

Swift shook his head. ‘They’ve banned vehicles up here, blocked off the access with boulders. The illegal off-roaders have caused so much damage it’s made it impassable in places.’

Kay Greenhalgh raised her head and then her eyebrows. ‘Are you really saying there’s no way to get out here in a vehicle now that the path’s blocked?’ She snorted quietly. ‘The weekend warriors might not manage it, even the ones with upswept exhausts and impressive sticker collections, but a good quad bike or tractor driver with local knowledge would get you out here, no problem, wouldn’t you say?’ She looked back at the corpse. ‘Or what about a pony? There’s nothing of him, you could easily sling someone that size over a pony’s withers.’

Julie also raised an eyebrow. Every time she met the pathologist, she was impressed by the breadth of her knowledge.

‘Fair point.’ Swift tugged at his ear. ‘Can we tell if hewasdumped?’

Greenhalgh shrugged. ‘It’s too sodden for there to be any tyre tracks, but the position of the body would suggest he’d been carefully placed, leaning against the rock.’ She looked at Swift. ‘Or he could have just banged his head on the rock, managed to right himself and then expired of course.’

Julie noticed the suspicion of disappointment cross Swift’s face at this possibility. ‘Do we know who he is?’ she asked the doctor.

‘There’s absolutely nothing to identify him. Nothing at all in his pockets, and he wasn’t even wearing a watch. There’s a signet ring but there’s nothing inscribed on it, no initials.’ Greenhalgh jiggled a plastic bag. ‘At least we think it must be his, although it’s not very big and it’s not actually attached to a digit. Could be a pinkie ring?’

‘Had the hand dropped off?’ Julie took the bag from Kay and examined the grisly contents. Along with the ring were several small bones.

‘Nope, too soon for that, and judging by the marks on the bones in the wrist, it looks as though a fox has had a go at it. Most of it was down there on the ground next to him.’ Greenhalgh retrieved the bag and held it up for Swift to see. There were several pieces of finger in the clear plastic bag. Flaccid skin still clung to the bones and the nails that were visible were bitten down to the quick. ‘I’m guessing the damage was post mortem.’

‘Thank goodness for small mercies,’ muttered Swift, dabbing his mouth with a large white handkerchief. ‘When do you think you’ll be able to fit him in for your ministrations?’

‘Seeing as it’s you, Craig, I’ll get it started first thing tomorrow morning. I’ll let you know as soon as I’ve got anything – unless you’d rather be there for the main event? I know you like a hands-on approach.’ She jiggled the evidence bag and Julie laughed

‘I could go, Sir?’

‘Ah yes, you and your gruesome penchant for a good PM, Sergeant.’

‘It beats paperwork, Sir.’

‘There’s nothing wrong with being interested in watching science at work, Craig.’ Greenhalgh stepped well away from the locus and removed the shoe covers from her wellingtons. She dropped them into a large evidence bag, which was being held open by one of the uniformed constables. ‘You might even learn something.’

‘I think I’ll leave it to the sergeant, if it’s all the same to you. It’s a relief to finally have a member of the team who enjoys all the blood and guts.’

Greenhalgh shook her head and began to walk away from them. ‘Oh,’ she said, turning back to face them. ‘There was one odd thing. His good hand is twisted slightly as though he’d been holding something. It might be nothing, it could have happened as he died – some sort of reflex action or spasm – or it could have been caused by a pre-existing condition. Anyway,’ she pushed back the hood of her SOCO suit, ‘Sergeant Kite and I can discuss it in more detail tomorrow.’

Swift and Julie watched Greenhalgh walk away.

‘So where does this bewildering love of necrotising flesh come from eh, Sergeant?’

Julie shook her head. ‘It’s not that ghoulish, Sir. I just find the whole forensic pathology thing fascinating. You can find out so much more about some people after they’re dead than when they were alive. There’s nowhere to hide anything, is there, on a slab?’

‘That’s far too much information for my liking.’ Swift curled his lip.

The two dark-coated men zipped the corpse into a black body bag and slid it onto the stretcher, and the Mountain Rescue team lifted it carefully between them. The entourage was moving en masse off the hill now, leaving the two uniformed PCs to carry out a final check and remove the tapes. A huddle of mountain sheep watched them approach. All but one fled. She looked up briefly, considered them carefully then put her head down and carried on grazing.

‘Given what we’ve got to go on, it might be an idea,’ said Swift, nodding towards the sheep, ‘to bring her in and take her hoof-prints.’

CHAPTER THREE

Day One

Julie’s first impression, as she slowly crossed the reception area towards Owen Lloyd, was that he had, outwardly at least, recovered from his ordeal out on the moors. He wore what looked like brand new and expensive white trainers but his grey skinny jeans were still mud-spattered from his rural exertions. His chin was buried in the folds of a red hoody and he sprawled untidily on the low reception seating, typing frenetically into his phone. Beside him, a dark-suited man wearing a sober shirt, navy tie and a pained expression, hissed urgently.

‘Can you try to look as though you’ve just found something shocking and not as though you’re lolling on a sun lounger?’

Owen groaned with his eyebrows but there was no deceleration of his thumbs stabbing at the screen.

‘Owen, are you listening? You’d better not be broadcasting this to all and sundry on that thing.’

‘No.’

‘No, you’re not listening?’

‘No, I’m not saying anything.’ Owen glanced sideways. ‘Not about that anyway. Mr Robinson asked me not to.’

‘Oh, so how can Mr Robinson get you to do as he wants?’

Owen stopped typing and sighed theatrically. ‘Becausehe treats me as though I’m a person and not just one gigantic disappointment.’

The boy’s body was angled away from his father; the father’s face was becoming increasingly flushed as the boy spoke. Julie held out her hand first to the younger Mr Lloyd and then accepted the limp handshake offered by his father.

‘Owen. Mr Lloyd. It’s good of you to come in this evening. Hopefully things will still be clear in your mind.’ Owen grimaced, but didn’t reply. ‘We’ve just a couple of questions, it’s nothing to worry about.’ She smiled at the father. ‘We’ll try not to take up too much of your time.’

In the interview room, Owen hurled himself into the plastic chair in the same position he had favoured in the reception area. His words were almost glib to begin with and each sentence was punctuated with shrugs as he told Julie about the expedition. No, he couldn’t remember where they had walked or what they had seen. When she asked if he had enjoyed the trip, he looked at her as though she had suggested he might like to give up social media and read a good book, but when she asked about what he’d found, out there up in the peat, he couldn’t hide his emotions.

‘I thought it was just a sheep. A black sheep.’ He looked up at her. ‘But then I got closer, and I could see it was a person.’ He took a jerky breath. ‘From the way it… he was sitting, I knew he would probably be dead, but I didn’t expect it to be like that.’

Owen’s father moved towards his son, but Owen shifted in his chair, edging away. ‘His skin, the skin on his face, it was gross. Bits of it were flaking off.’ He swallowed and sniffed quietly. Both adults pretended they hadn’t heard, but then Owen caught his breath in a half-sob.

‘Do you want to take a break? Should we stop and let you get a drink?’ Julie ducked her head so she could see under the hood. ‘Or we could do this tomorrow if you’d prefer?’

Owen shook his head. ‘Let’s get it over with now, and then I can forget about it.’

His father shot Julie a look which confirmed they were both aware that for Owen to forget what he had seen might take far longer than the boy realised.

‘Well just say if you do want to stop. OK?’ Julie waited for the small nod before moving on.

‘Did you touch anything?’

‘Why would I want to do that?’

‘I just need to know whether you might have dislodged anything, can you remember?’

Owen shook his head. ‘I didn’t touch it or anything near it. It was all totally gross.’

‘And you weren’t wearing those trainers earlier this afternoon?’

‘Obviously not, Sergeant.’ Mr Lloyd was controlling his contempt with difficulty.

‘Well, would it be all right if we had a look at the boots you were wearing, just so that we can eliminate any marks you may have made at the location from the results of our forensic examination.’ She turned to the father. ‘Perhaps you could bring them in first thing tomorrow. If you could put them in a clean plastic bag that would be a big help.’ Mr Lloyd suddenly looked less confident and Owen’s eyes widened.

‘I didn’t do anything, I swear.’

Julie smiled at him. ‘It’s OK, don’t worry. You’re doing great. I’m not saying you would have touched anything, Owen, and if you did, that’s understandable, given what you experienced out there. We just have to know if everything was in the same place as when we saw it, that’s all.’

‘I didn’t move anything. I didn’t want to touch it, any of it.’

‘That’s fine. So there was nothing with the… there were no belongings?’

Owen stuck his chin out and Julie waited for the defiant response, but instead, out of nowhere, he began to sob. ‘It… there were flies and maggots everywhere… it looked as though he was still moving.’ He swiped his sleeve across his face. ‘They were crawling all over his face, in his mouth, but he couldn’t feel them.’

Owen’s father was out of his chair now, holding on to his son, both arms wrapped tightly around him, his chin resting on the top of Owen’s hooded head. Owen made no move to push him away. Julie waited until Mr Lloyd let go, until he had rubbed Owen’s back self-consciously and sat back down in his chair.

‘That’s fine, Owen. You’ve been brilliant. If you think of anything else that might help us…’ Julie paused in the face of a stare from Mr Lloyd. It was easy to see which parent Owen had inherited his impressive facial expressions from.

‘I think I’m ready to take my son home now, Sergeant, if that’s all right with you.’

Julie watched them walk out of the building. Mr Lloyd had an arm firmly round Owen’s shoulders and the boy was leaning into his father. She realised Brian Hughes was watching her from behind the reception desk.

‘All right, Julie?’

‘I think I upset the poor lad. He’ll have nightmares.’

‘He’d have had nightmares anyway after seeing something like that.’ Brian smiled. ‘But I think you’ve just helped to improve a pretty dodgy father-son relationship. For a little while anyway.’

Swift was standing by the board and Rhys was writing down, in neat colour-coded sections, all the information they had so far. There was very little there. Julie watched Rhys stick a photograph of the body and a section of the local Ordnance Survey map on the board. A red dot marked the location where the body had been found.

‘Sorry, Sarge,’ Rhys said as she went to stand next to him.

‘What for?’

‘Well, I know you’re not too keen on corpses on the board, are you?’

‘We don’t have much of an alternative this time, do we?’ She grimaced at the photograph. ‘Besides, it’s not the gruesomeness I’m bothered about, although this one is pretty spectacular in that department.’ She stepped back and looked at the photograph, the map and the rest of the sparse information. ‘I’d just rather see the deceased as they were, as a living, smiling person. It makes it seem even more important that we find out what happened to them.’

‘If you say so, Sergeant.’ DI Swift gave her the slightly nonplussed look he’d bestowed on her at regular intervals since her arrival on his team as an eager, newly promoted detective sergeant. ‘So, what do we think?’

‘He could have been a walker.’ Goronwy offered.

‘Do people walk on their own in places like that?’ Julie asked.

‘There are all sorts of oddballs up in the hills,’ Morgan Evans offered.

‘You’re doing your charitable human being thing again then, Morgan?’ Julie laughed, still unsure of him, and whether he would see the joke, get her sense of humour.

‘It’s true though. Loads of people go walking on their own. What about your Adam?’

‘So you’re saying he’s an oddball?’

Morgan cocked his head on one side. ‘He does go out running on his own, Sarge.’

Julie couldn’t tell from his deadpan expression whetherhe was joking now.

‘Fair point.’ Swift stepped between them. ‘There could be lots of reasons why he was out there on his own. He could have been working out there or walking or any number of other things.’

‘Maybe he was checking sheep.’ Rhys said. ‘Or looking at wildlife or something. Rhian’s brother’s into all that Iolo Williams nature stuff. He goes all over the place with his binoculars.’

‘At least he says it’s wildlife, eh?’ Goronwy attempted to look innocent.

‘He was drunk at that wedding, you know he was, boy.’ Rhys wagged his whiteboard marker towards his annoying cousin.

‘Thank you, children and just for your information, there were no binoculars or anything else found with the body.’ Swift tapped the map on the board. ‘So he could have been on his own, but if he wasn’t, then who would have left him out there? Could he have been separated from a group and got lost?’

‘He’s not far enough off the path for that though, is he?’ Julie watched Rhys write ‘Why was he there?’on the board. ‘Even if he’d had a heart attack or a fall or something, and was on the ground, they’d still have seen him if they came back to look for him. There’s no cover up there at all. There’s no way they’d have missed him.’

‘So that leaves the possibility that someone left him there knowingly.’ Swift shook his head. ‘Or that he died of natural causes and bashed his head on his way down.’ He pursed his lips. ‘Although I’m not at all convinced about that idea. Well, we’ve absolutely nothing at all to go on so we’d better start with missing persons. Could you do that now, Goronwy, please.’ Swift waited for Goronwy’s acknowledgement before moving on. ‘I’m not aware of anyone from the area having been reported missing, but we need to make sure. It’s more likely he’s from off, so you’d better make it fairly broad. If he was a tourist, then he could have been staying locally, so we’ll need to start with hotels, B&Bs and campsites in and around Rhayader and work outwards.’

‘There might be a car somewhere, Sir?’ Julie said. ‘He didn’t get there on public transport, did he?’

‘You’re right, Julie. Morgan, see if anyone’s reported an abandoned vehicle and try the car parks and the Visitors’ Centre in the Elan Valley. And get Traffic to keep an eye out for anything that could have been abandoned in a layby.’

‘He could have come from the other end though, from Pontrhydfendigaid, couldn’t he?’

‘Good point, Morgan, he could.’ Swift checked the map again. ‘So, Julie, first thing tomorrow, you’re going to go and find out more about our corpse. Morgan can check out the towns at the other end of the Monks’ Trod.’ He scratched his ear. ‘Rhys and Goronwy can tackle accommodation in Rhayader for a kick off, see if any of their guests didn’t come home recently. I’ll make a start on the hill farms and we’ll compare notes later tomorrow morning, unless anything earth-shattering comes to light before that.’ He ambled off towards his glass-fronted office. ‘Sergeant Kite and I will touch base after the PM,’ he shouted back at them. ‘I think she and I may need to go and ask a few questions in Llandrindod.’

Morgan Evans rolled his eyes and Julie laughed.

CHAPTER FOUR

Day One

Julie chased the last grains of risotto rice round her plate and picked up her wine glass. ‘You’re getting better at this cooking thing,’ she said. ‘You’d never know that was veggie.’

Adam carried both plates to the sink. ‘Thank you for the back-handed compliment,’ he said, gazing at the pile of pans and chopping boards balanced on the draining board. ‘And you’d never know that you’d agreed to do the washing up.’ He sighed. ‘There’s nothing wrong with vegetarian food either. It’s not all lentils and mushrooms, you know.’

‘You have to admit though, you do get through the lentils. And the beans.’

‘You like beans.’

‘Only baked beans, preferably cold and straight from the can.’

‘You’re a heathen. And that rather splendid risotto you just devoured was actually vegan.’

‘I’ve told you. You’ll not convince me in a million years to go vegan. I need bacon butties and shepherd’s pie, there’s no way I can think on a diet of rabbit food.’

‘Your little grey cells will be fine with plant-based sources of protein, believe me.’ Adam dribbled washing up liquid onto the plates in the sink and turned on the tap. ‘Your diet is horrendous.’

‘There’s nothing wrong with my diet. It’s better than a lot of people’s.’

‘It’s better than Helen’s, I’ll grant you that. God knows what she’s eating now you’re down here. At least you cured her of the Mars bar for breakfast habit. She’ll be back on the kebabs and the stuffed-crust pizzas by now.’

‘I should see if there’s a job going at the station for you. You’re like the food police. There must be nothing worse than a newly converted vegan. And just so you know, I absolutely refuse point blank to feel guilty about pizza.’

‘It’s your body, it’s up to you whether you want to look after it.’ Adam rinsed a plate under the tap and gave her hisyou know I’m rightexpression. God, he was positively angelic when he got going. It almost made her want to take up smoking.

‘What can you tell me about the Monks’ Trod?’ she asked.

‘Are you changing the subject by any chance?’

‘Possibly.’ She smiled as he pulled off bright orange rubber gloves and folded them carefully over the tap. ‘But I’m serious. We were out there today and I’d love to know what made people totter about up there centuries ago, and why they still do. There’s absolutely nothing for miles. Except mud and very smelly water.’

‘So there’s been foul play in the Cambrian Mountains.’

‘Something like that.’

‘Come on, Jules, you know I’ll find out by this time tomorrow, anyway.’

‘Even though you’re in school tomorrow? Do you think the jungle drums will reach you that fast down in Builth then?’

‘You never know. Anyway, I might feel the need to go for a long bike ride after school. For training purposes. There are some brilliant hills over that way.’

Julie shook her head, but she was smiling. ‘OK. You win. Yes, there has been foul play in the Cambrian Mountains. Possibly. Up above Pont ar Elan. We don’t know yet and it could quite easily be natural causes, although Swift is not chuffed at that idea, obviously. I’m off to the post mortem first thing, and the others are making a start asking questions in Rhayader and Pontreedsomething.’

‘Do you know who it is?’

‘It’s probably just a walker who was taken ill out there on his own. Poor old thing.’ She shrugged. ‘Well, I say old, but there’s nothing of him. He’s probably much more likely to be a teenager.’

Adam poured more wine into Julie’s glass, screwed the top back on the bottle, returned it to the fridge and sat back down at the table. ‘Well I don’t know a huge amount about it,’ he said. ‘I do know the track was part of a longer one, leading from the abbey at Strata Florida to the one at Abbeycwmhir, hence the Monks’ Trod. I think it was Benedictine monks who used it originally, and then after the dissolution of the monasteries, it became more of a drovers’ road.’

‘And what did the drovers actually do?’

‘They moved livestock for a living, cattle and sheep and even geese. On foot, can you believe that? They even took them as far as London. Can you imagine how hard that must have been? It’s got to be two hundred miles from here.’ Adam was suddenly animated, in teacher mode. ‘They used dogs to help them – corgis a lot of the time – and when they got to London, they’d just send the dogs back. On their way home, the dogs would stay in the same lodgings they had stayed in with their masters on the way down.’

Julie laughed. The kids would love it, imagining corgis running about all over the country looking for digs. They’d love Adam’s enthusiasm too. ‘I’m glad you don’t know very much about it.’

Adam looked hurt until he saw her face and he smiled. ‘Yeah, all right, Sergeant Sarky, but I can find out more for you. I’ll go to the reference library in Brecon tomorrow and check it out.’

‘And there I was, wondering what you’d do with yourself all summer. You’re loving this, aren’t you?’ She laughed, but Adam’s features had rearranged themselves into a frown. She bent to get a better look at him but he moved his head away.

‘Jules.’ Adam picked at the corner of his place mat and looked away, out of the window to the hills beyond.

‘Go on.’

‘I don’t want you to over-react. Promise me you’ll stay calm.’

‘What have you done, ordered yet another bike? Bought a new wetsuit? Told your mum and dad they can stay for a month?’

‘Seriously, Jules, I need to tell you something important.’

Julie leaned back in her chair and folded her arms. Her stomach was suddenly doing somersaults.

‘This sounds ominous.’

‘No, honestly, it’s really not that bad. The thing is… I just don’t want you to find out any other way and get the wrong idea. You know what you’re like with that imagination of yours.’

‘Find out what, Adam?’ There was no response, and he still refused to meet her gaze, so Julie bent forward, into his eye line. ‘What is it?’ Adam looked down at the table and fiddled with his mat until she slid it out of his reach. ‘Tell me. Is there something wrong with you?’

He shook his head. ‘It’s fine. Everything’s good, nothing to worry about, honestly. But you need to know in case there are phone calls.’ He closed his eyes. ‘Just in case she phones.’

Julie’s hand tightened round her wine glass. ‘She?’

‘She’s just being daft. It won’t come to anything.’

‘You’re not trying to tell me that she’s at it again? It’sher, isn’t it, it’s bloody Tiffany.’

Adam nodded miserably. ‘You know what I told her at the Christmas party. I couldn’t have made it any clearer that it was over, could I? And there was no doubt she definitely got the message, given the names she shrieked at me as she left the pub. And that was months and months before we moved here. And I showed you the letter I sent her in January. For God’s sake, you even edited it.’ Adam stopped and took a much-needed breath, finally meeting her stare. ‘And before you ask, yes, I did post it.’

Julie took a large gulp of wine. ‘So, what’s the barmy cow done now then?’ She willed herself not to over-react, not to pick up the wine glass with its slender pale green stem and hurl it at the newly decorated wall.

‘It’s nothing much, honestly, she’s just been texting again.’

‘What did she say?’

Adam shrugged. ‘She said she needed to talk to me.’

‘And that was all?’

‘She said she had something to tell me and that she would rather do it face to face.’

Julie stared at him. ‘And what do you think that could be, Adam?’

‘I have no idea, but I’d lay odds it’s not what you’re thinking.’

‘How do you know what I’m thinking?’

‘I know you. And to be fair, I’d be thinking the same thing, except that I know it’s not possible.’

Julie watched his face. ‘But you said you’d changed your phone number.’

‘I did change it. Don’t be soft, Jules, you know I’ve got a different provider, a new number, everything.’

‘So how has she got hold of your new number?’ Julie wanted to reach for the glass again but instead she forced herself to sit still and breathe slowly and evenly. He’d promised he wouldn’t ever stray again, hadn’t he?

‘Adam, how has she found you?’

Adam looked up at the ceiling. When he eventually faced her again, she knew from experience that he was telling her the truth. ‘It was Fran.’

‘Hadleigh High Fran?’

Adam nodded. ‘Tiff was in doing some supply teaching, just after the May half term, and she persuaded Fran she needed Derek Jamieson’s number to talk to him about a pupil of his. Fran said Tiff was worried about the girl, she thought she might be being abused at home. Fran says she just brought the staff phone book up on the computer with Tiff standing there and didn’t think anything of it.’

Julie refolded her arms and leaned back in her chair. ‘And what with your number being next on the list to good old Mr Jamieson’s?’

‘I knew you’d be able to work it out.’ Adam gave a little smile and waited for Julie to reciprocate. She didn’t. ‘But what do I do about it?’

Julie unfolded her arms, rested both elbows on the table and gazed at him, using the blank stare she used to make suspects squirm in interview rooms. It had the desired effect. ‘She doesn’t know your address?’

Adam blushed and shook his head. ‘Fran had only put the phone number on the list in case of any queries but she hadn’t put our new address on the computer, thank God.’ He traced the edge of the table with his finger. ‘She said she couldn’t spell it. So no, Tiffany doesn’t know where we live.’

Julie nodded. ‘Good. That’s something, at least. Let’s hope it stays that way. You’d have thought a school secretary would be a bit more cautious with personal details, wouldn’t you?’

‘Oh come on, Jules, that’s not fair. You know Fran, she’s so careful with any information about the kids. She was just trying to help. You’d never imagine that you’d have to keep a teacher’s details private from a colleague, would you?’

‘Wouldn’t you?’ Julie arched an eyebrow. ‘So what did you do when you got the texts?’

‘I didn’t do anything.’

‘You haven’t replied to her?’

‘Well, yeah, I did reply to the first couple, just to tell her to leave me alone, but I’ve not answered the rest. I promise.’

Julie stood up and walked to the fridge. She retrieved the wine bottle and filled her glass almost to the brim, leaving the chilled bottle on the table. She could see Adam resisting the urge to slide a coaster under it, but he stayed where he was.

‘Say something, Jules.’

‘What do you want me to say? You promised me before we even moved here that it was all over.’ She shrugged. ‘If I hadn’t believed your promise, then I wouldn’t be here would I? If you really haven’t said anything to encourage her, then it’s not going to be a problem, is it?’ Julie watched Adam relax as though someone had released the stopper from a beach ball.

‘Thank you.’ He leaned across the table and gave her free hand a clumsy squeeze. ‘I didn’t know what you’d say.’

She shook her head and picked up her glass, sipping slowly. ‘I wasn’t too sure either, to be honest.’

Adam’s lopsided grin was one of the things that had made her fall for him in the first place and he knew when to use it. ‘So what can we do?’

‘I don’t think there’s anything we can do, is there? If she’s only sent a couple of texts and you’ve left her in no doubt as to where she stands, then we just have to hope she’ll get the message. If she’s no idea where you live, then what can she do?’

‘Julie Kite, I don’t deserve you.’ Adam kissed the top of her head and then sank back down into his chair.

‘You don’t, Mr Kite. Now pass me the Pringles.’