28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Crowood Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

The Rolls-Royce company acquired Bentley Motors in 1931 and, although models continued to be produced with the Bentley name, they increasingly used many Rolls-Royce components. By the time the Silver Cloud and Bentley S were released in 1955, they were really differently badged versions of the same design. Yet the sporting tradition of the Bentley marque was upheld with the exotic Continental models that were derived from them. The Silver Cloud family represents a pinnacle for the Rolls-Royce company. The cars all had and still have a very special presence, and the standard saloons have an unsurpassed elegance and rightness of line. The special-bodied cars, meanwhile, are reminders of an age when the skill of the best coachbuilders was something deserving of universal admiration. With around 190 photographs, this book features: The story of the design and development of the Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud and Bentley S Type; A look at the production development of these cars between 1955 and 1965; An examination of the Bentley Continental models that were derived from Silver Cloud and S Type design; The history of the Phantom V and Phantom VI limousine chassis introduced in 1959 and destined to last until 1990; Full technical specifications, including paint and interior trim choices; Production figures and chassis codes and finally, a chapter on buying and owning one of these wonderful classic cars.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 297

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

TITLES IN THE CROWOOD AUTOCLASSICS SERIES

Alfa Romeo 2000 and 2600

Alfa Romeo 105 Series Spider

Alfa Romeo 916 GTV and Spider

Alfa Romeo Spider

Aston Martin DB4, DB5 & DB6

Aston Martin DB7

Aston Martin V8

Audi quattro

Austin Healey 100 & 3000 Series

BMW M3

BMW M5

BMW Classic Coupés 1965–1989

BMW Z3 and Z4

Citroen DS Series

Classic Jaguar XK: The 6-Cylinder Cars 1948–1970

Classic Mini Specials and Moke

Ferrari 308, 328 & 348

Ford Consul, Zephyr and Zodiac

Ford Transit: Fifty Years

Frogeye Sprite

Ginetta Road and Track Cars

Jaguar E-Type

Jaguar Mks 1 and 2, S-Type and 420

Jaguar XJ-S

Jaguar XK8

Jensen V8

Land Rover Defender

Land Rover Discovery: 25 Years of the Family 4×4

Land Rover Freelander

Lotus Elan

MGA

MGB

MGF and TF

MG T-Series

Mazda MX-5

Mercedes-Benz ‘Fintail’ Models

Mercedes-Benz S-Class

Mercedes-Benz W113

Mercedes-Benz W123

Mercedes-Benz W124

Mercedes-Benz W126

Mercedes SL Series

Mercedes SL & SLC 107 Series 1971–2013

Morgan 4/4: The First 75 Years

Peugeot 205

Porsche 924/928/944/968

Porsche Air-Cooled Turbos

Porsche Boxster and Cayman

Porsche Carrera: The Air-Cooled Era

Porsche Carrera: The Water-Cooled Era

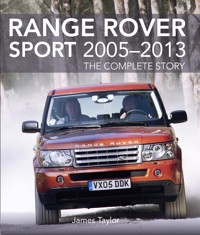

Range Rover Sport

Range Rover: The First Generation

Range Rover: The Second Generation

Reliant Three-Wheelers

Riley: The Legendary RMs

Rover 75 and MG ZT

Rover 800

Rover P4

Rover P5 & P5B

Rover SD1

Saab 99 & 900

Shelby and AC Cobra

Subaru Impreza WRX and WRX STI

Toyota MR2

Triumph Spitfire & GT6

Triumph TR6

Triumph TR7

VW Karmann Ghias and Cabriolets

Volvo 1800

Volvo Amazon

First published in 2021 byThe Crowood Press LtdRamsbury, MarlboroughWiltshire SN8 [email protected]

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2021

© James Taylor 2021

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 968 6

Cover design by Blue Sunflower Creative

CONTENTS

Introduction and Acknowledgements

Timeline

CHAPTER 1FOREBEARS AND EXPECTATIONS

CHAPTER 2DESIGN, DEVELOPMENT AND PROTOTYPES

CHAPTER 3THE 6-CYLINDER MODELS, 1955–1959

CHAPTER 4THE 6-CYLINDER CONTINENTALS

CHAPTER 5SILVER CLOUD II AND BENTLEY S2

CHAPTER 6PHANTOM V, 1959–1968

CHAPTER 7SILVER CLOUD III AND BENTLEY S3

CHAPTER 8THE V8-ENGINED CONTINENTALS

CHAPTER 9SPECIAL BODIES ON STANDARD CHASSIS

CHAPTER 10PHANTOM VI, 1968–1990

CHAPTER 11WHAT CAME AFTER: SILVER SHADOW AND T TYPE

CHAPTER 12PURCHASE AND OWNERSHIP

Appendix: How Much Did They Cost?

Photo Credits

Index

INTRODUCTION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To my mind, these Rolls-Royce and Bentley models epitomized all that was good about the two marques, and they have gone on to become some of my favourite cars in the years since they were current. I still remember the early examples as a source of wonder when I was a child – and I remember being bitterly disappointed that there was never a Dinky Toy model of the Silver Cloud to request for Christmas!

Many years on, I still believe the Silver Cloud family represented a pinnacle for the Rolls-Royce company. The cars all had, and still have, a very special presence, and the standard saloons have an unsurpassed elegance and rightness of line. The special-bodied cars, meanwhile, are reminders of an age when the skill of the best coachbuilders was something deserving of universal admiration.

The Silver Cloud family has been the subject of many books, and I doubt that this one will bring any new knowledge to print. Nevertheless, I do hope it will make the story of these fine cars more widely available, and at an affordable price.

Assembling the information needed for this book sent me ferreting through my library to find the best sources of information, and I will single out two books in particular that proved useful. One is Rolls-Royce and Bentley Experimental Cars by Ian Rimmer; the other is Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud I and Bentley S1 – 50 Years, by Davide Bassoli and Bernard L. King. The photographs have been gathered from multiple sources, and I am pleased to thank Magic Car Pics, Simon Clay, Nigel Smith and Tom Clarke for their help, as well as the generous souls who have made their work available through Wikimedia Commons.

JAMES TAYLOROxfordshire

TIMELINE

1952

First experimental Siam prototype completed

1955, April

Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud and Bentley S Type announced

1955, October

First public display of the new models at the Earls Court Motor Show

Announcement of Bentley Continental

1957, October

Announcement of long-wheelbase touring limousine derivatives

1959, October

Introduction of V8-engined Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud II, Bentley S2 and Bentley S2 Continental

Introduction of Rolls-Royce Phantom V limousine models, also with V8 engine

1962, October

Introduction of Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud III, Bentley S3 and Bentley S3 Continental

1962, October

Revised front end for Phantom V, to match Silver Cloud III and other new models

1964, summer

Availability of Continental-type bodies for Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud III

1965, August

Last Bentley S3 built

1965, October

Last Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud III built

1965, November

Last Bentley Continental S3 built

1968, June

Last Phantom V delivered

1968, October

Rolls-Royce Phantom VI announced

1972, spring

Major changes to Phantom VI to meet European safety regulations

1978, spring

Larger (6750cc) engine, new gearbox and revised brakes for Phantom VI

1990

Last Phantom VI chassis built

CHAPTER ONE

FOREBEARS AND EXPECTATIONS

The Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud and Bentley S Type twins were not designed and developed in a vacuum, but were carefully drawn up to meet existing customer expectations of the two marques, and where possible to exceed those expectations. So before looking at the story of the cars themselves, it is important to understand them in their proper context.

It is certainly arguable that the first contribution to the cars that were launched in spring 1955 was a series of discussions held within the Rolls-Royce company towards the end of the 1930s. At that stage there were three model ranges in production: the Bentley 4¼-litre, the Rolls-Royce Wraith, and the Rolls-Royce Phantom III. There was a degree of common componentry between each model and the next, but the range had grown up in a rather piecemeal fashion, and was expensive to produce. Senior management at Derby, where the company then had its headquarters, concluded that the range was too diverse. What was needed for the future was rationalization.

The Phantom remained the larger Rolls-Royce, and from 1935 was in its third iteration as a Phantom III, with a complex V12 engine. This elegant Barker-bodied example dates from around 1937.

This remarkable 1936 Phantom III was bodied by HJ Mulliner, with a forward-sloping windscreen that supposedly made it more aerodynamic. Built for the Chairman of the De Havilland Aircraft Company, it later passed to Field Marshal Montgomery.

The emphasis in the 1936 Phantom III was on comfort for the rear-seat occupants. The cords behind the seat operate a blind to cover the rear window.

A number of schemes were considered before the outbreak of war in 1939 brought a temporary halt to car production. More were considered as the war drew to a close in 1945, by which time the company had moved to new headquarters at Crewe. Fortunately, Rolls-Royce did not have to start completely from scratch with the design of their post-war cars, as ideas and prototype hardware had existed by the end of the 1930s. However, many promising and interesting ideas were discarded, and the post-war range was, in effect, the minimum of what potential customers might expect from the two marques.

Rolls-Royce had never built its own bodywork, but had always depended on specialist coachbuilders to provide bodies for its chassis. So the first consideration was a new chassis, and the company decided to make what were, in effect, two versions of the same design. There would be one for the owner-driver models, and one with a longer wheelbase to allow for roomier coachwork for the models that were typically chauffeur driven. These two chassis could clearly share the same engine.

The owner-driver models took on the independent front suspension of the Phantom III during 1938 to become the Wraith. This 1939 example has coachwork typical of the period, and carries the personal number-plate of the major London Rolls-Royce agent, Jack Barclay.

After World War II, Rolls-Royce relocated from Derby to Crewe, where it had earlier operated an aero-engine factory. This picture was taken in the mid-1960s, with Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud III and Bentley S3 models in evidence; the factory is now the home of Bentley Motors.

Rolls-Royce did not build their own bodies, but left it to specialists. This was the extravagantly luxurious interior of a 1920s Phantom I (the larger, chauffeur-driven model) with coachwork by Charles Clark of Wolverhampton.

After the original Bentley company collapsed in 1931, it was bought by Rolls-Royce. From 1933, new Bentley models used Rolls-Royce mechanical components and were marketed as the ‘silent sports car’.

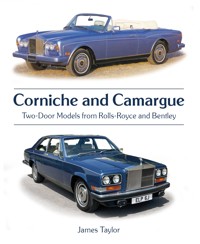

During the late 1930s, Rolls-Royce was investigating a streamlined, high-speed Bentley that it called the Corniche. The original car did not survive the war, but Bentley Motors created a faithful copy from the original plans in 2019, the year of Bentley’s 100th anniversary.

The origins of the engine design for the first Silver Clouds can be traced right back to the Rolls-Royce Twenty of the 1920s – the ‘small’ or ‘junior’ model. Here, a preserved example is being driven with some enthusiasm along London’s South Bank.

The Rolls-Royce aero-engine division was as important a part of the company as the car division, and in the 1930s created the legendary V12 Merlin aero engine that proved vital to the success of the RAF during World War II.

Built in tiny numbers and for Heads of State only, the Rolls-Royce Phantom IV had an 8-cylinder version of the company’s post-war engine.

That engine would be a new one. The ohv 6-cylinder that had powered the owner-driver models in pre-war years was by now relatively old, having been introduced as long ago as 1922. Although it had been updated in two major stages since then, it had really reached the limit of its development and needed to be replaced by a more modern design. As for the V12 engine that had powered the Phantom III, Rolls-Royce was probably only too pleased to see the back of it. Although it was a quite remarkable power unit in its own right, it was both expensive to make and intolerant of poor maintenance.

So just one new engine was drawn up to replace both. It was deliberately designed to be expandable, both in terms of its swept volume and in terms of the number of cylinders. For now, Rolls-Royce decided 6 cylinders would be enough, but the idea of an 8-cylinder derivative never went away – and indeed would eventually materialize as the engine of the exclusive ‘Heads of State only’ Rolls-Royce Phantom IV in the early 1950s. Although the cylinder block of the new engine was a clear descendant of the one that Henry Royce himself had drawn up for the Rolls-Royce Twenty a quarter of a century earlier, central to the basic design was a new and highly efficient combustion chamber that was created by combining overhead inlet valves with side exhaust valves; this layout was usually known as the F-head or IOE type. It had been well proven in the Rolls-Royce B range of military-vehicle engines during the war.

With these basic building blocks, Rolls-Royce believed they could create a range that consisted of three models, like the range of the late 1930s. There could be an owner-driver Rolls-Royce, a more sporting Bentley, and a large Rolls-Royce for chauffeur-driven duties. However, this neat arrangement came to grief as a result of the company’s plans for coachwork. What was perhaps the most radical element of the post-war rationalization plan was that there would be a standard body for the owner-driver car, and that it would be made for Rolls-Royce by Pressed Steel, who manufactured all-steel bodies from pressings in large volumes for many other car makers. It would, of course, be trimmed on the assembly lines at Crewe, to the standards that Rolls-Royce buyers had come to expect.

There was some nervousness about this idea at Crewe. Would the traditional Rolls-Royce customer baulk at buying a car with bodywork that had been stamped out by machines at high volume alongside similarly constructed bodies for makers such as Austin and Morris? That nervousness won the day, and so the decision was taken to make the standardized coachwork available only for Bentley models in order to protect the Rolls-Royce image. For those who insisted, the Bentley chassis could be made available on its own for bespoke coachwork, just as the chauffeur-drive Rolls-Royce chassis would be. That would preserve some sort of decency. But there would be no Rolls-Royce version of the owner-driver model – or at least, not yet.

Central to the post-war car range was a new 6-cylinder engine. This illustration comes from a sales brochure for the Bentley MkVI.

So it was that when the new post-war range from Crewe was announced in the early spring of 1946, there were just two models. The chauffeur-drive model was launched in April 1946 with the name of Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith, and the owner-driver car arrived a few weeks later as the Bentley MkVI.

This two-model strategy worked very well, perhaps helped a little by the fact that buying a car of any sort was difficult in the immediate post-war years. Customers were very happy with what became known as the ‘standard steel’ Bentley, and those who had the means and the inclination to order bespoke coachwork on the Bentley chassis were, of course, still at liberty to do so. The principal effect of Rolls-Royce offering a complete owner-driver model, rather than only the chassis for it, was on the independent coachbuilders. Inevitably it hit demand for their work, and that at a time when there was an increasing dearth of separate-chassis cars for them to work on anyway. As far as the Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith was concerned, however, it seems to have been very much business as usual.

Nevertheless, that two-model strategy did not satisfy everybody. In the late 1940s, the British Government encouraged car makers to export a large percentage of their production in order to bring cash into an economy that had suffered badly during the war; ‘encouraged’ is perhaps too much of a euphemism, because there was talk of cutting supplies of rationed steel to those who did not comply. Meanwhile, there was a growing demand for British cars in the USA, partly at least thanks to the recent familiarity that American GIs posted to Britain had gained with them. Rolls-Royce was determined to claim its piece of that large market, although in practice no LHD chassis suitable for export to the USA would be available until 1949.

Post-war rationalization slimmed down the car range considerably. The Rolls-Royce Silver Dawn was initially an export-only version of the Bentley MkVI, and shared its ‘standard steel’ coachwork. This is a LHD example from the early 1950s.

Special coachwork nevertheless remained available on both Bentley and Rolls-Royce chassis. This beautiful drophead coupé was built by Park Ward on a Silver Dawn chassis in 1952.

It was US exports that created the problem. Rolls-Royce wanted to sell both its owner-driver car and the Silver Wraith in the USA, but realized that the Bentley name was not at all well known on the far side of the Atlantic. American customers were going to baulk at paying Rolls-Royce prices for the Bentley MkVI, a car that did not have the prestige of the Rolls-Royce name. The obvious solution was to offer them a version of the car with Rolls-Royce badges, and to revive the earlier plan for such a car.

In fact, things were not quite that simple. Rolls-Royce decided it would also sell the new owner-driver model – to be called the Rolls-Royce Silver Dawn – in other overseas markets, and in some of those it would be sold alongside the Bentley MkVI. There had to be some differentiation between the two models beyond simple badge and radiator grille differences. As a result, the Silver Dawn (which was built strictly for export only in the beginning) was given the Silver Wraith engine with its single carburettor instead of the more sporting Bentley version with twin carburettors.

This arrangement preserved the sporting associations of the Bentley marque while delivering a rather more sedate Rolls-Royce that seemed suitable for the traditions of that marque. The Silver Dawn was introduced in April 1949, and became the first post-war model from Crewe to be made available with left-hand drive. Just to confuse matters, however, LHD Bentleys were also supplied with the single-carburettor engine!

As post-war austerity was beginning to lift, Rolls-Royce stunned the motoring world with its 120mph (193km/h) Bentley Continental. The car had evolved from ideas for the pre-war Corniche project, and shared its chassis with the owner-driver Bentley models of the day.

As the post-war car market settled down, Rolls-Royce prepared to make upgrades to all three of its models. First came a big-bore, 4½-litre development of the original 6-cylinder engine that became standard across the range in October 1951. Then during 1952, the wheelbase of the Silver Wraith was extended by 6in (15cm) – although the older chassis also remained available into 1953 – and the rear chassis of the two owner-driver models was extended to provide room for a larger boot. (In practice, some coachbuilders had already been making their own chassis extensions to support just such a feature on coachbuilt bodies.)

The Silver Dawn remained a Silver Dawn, but the Bentley changed its name. Although developed as the Bentley MkVII, it was clear that it could not be called by that name for public consumption because Jaguar’s William Lyons had cheekily appropriated the MkVII name for his own big saloons. So instead, the Bentley became an R Type, its name derived from the fact that the first of the new chassis were numbered with R-series prefixes.

The really big news during 1952, however, was the introduction of a fourth model. In many ways, the arrival of the Bentley Continental was a symbol of the easing of post-war austerity, even though rationing in Britain would not come to an end until 1953. The new Continental was drawn up as a glamorous, highspeed, long-distance touring car that would be ideally suited to the unrestricted roads of the European continent. Its chassis was essentially that of the existing Bentley with its 4½-litre twin-carburettor engine, but with taller gearing and other modifications.

The earliest examples were contemporary with the Bentley MkVI and shared many of its chassis details, but from summer 1953 the Continental chassis would take on new features from the R Type. The majority of those built had this later specification, and as a result the car is now almost universally known as an R Type Continental to distinguish it from later models with the Continental name.

Continentals were capable of 120mph (193km/h) – an astonishing speed for such a large car in the early 1950s – when fitted as intended with the lightweight coachwork drawn up by Rolls-Royce and built by HJ Mulliner. However, many customers demanded additional fittings to heighten the Continental’s luxury credentials, and of course Rolls-Royce also made the chassis available for bespoke coachwork. As a result, the cars put on weight, and in 1954 Crewe decided to bore out the engine to 4.9 litres to compensate. This would be the final enlargement of the 6-cylinder engine, and when first introduced it would be available only for the Continental. Behind the scenes, though, Rolls-Royce was planning to use it in the new models that they were preparing for introduction in 1955.

Two other developments that took place in 1952–1953 need to be mentioned. One was the change in autumn 1953 to all-welded chassis frames from the traditional Rolls-Royce rivetted types (the actual design of the frames was not otherwise altered). The other actually occurred first in the summer of 1952, and was the introduction of an optional automatic gearbox. All Rolls-Royce and Bentley models up to this point had used the company’s own four-speed manual gearbox, with its tailshaft arranged to drive a friction-disc mechanical servo for the brakes.

The new automatic gearbox was not a Rolls-Royce design, but had been designed by General Motors in America; Rolls-Royce had obtained a licence to build it at Crewe, and to modify it to suit its own requirements – which included adding a take-off for that friction-disc brake servo. The GM Hydramatic had four forward speeds with a fluid flywheel, and had initially entered production as an option on 1941-model Cadillacs. Rolls-Royce had shown an interest in it from the start, but held off while their customers remained content with manual gearboxes. All the first automatic R Types were built for export markets, where demand was expected to be greatest, but from October 1953 they became available for home-market customers as well. The automatic gearbox simplified the driving experience to such an extent – and its manual over-ride functions allowed it to be used much like a manual box if the driver so wished – that it soon became a favourite.

The ‘large’ post-war Rolls-Royce introduced in 1946 was the Silver Wraith, which had a version of the new 6-cylinder engine in the Bentley MkVI. This one has a landaulette body, with a folding top over the rear passenger seat.

So by the time Rolls-Royce was ready to settle the production specification of its new cars – and the story of their development is told in the next chapter – there were four models to replace. Two wore Bentley identification: the R Type owner-driver saloon, and the high-performance Continental grand tourer. Two wore Rolls-Royce identification: the Silver Dawn owner-driver saloon, and the Silver Wraith limousine chassis. The buying public would expect the new models to offer performance at least equal to that of the ones they replaced, and they would also expect an automatic gearbox to be available, at least as an option.

The new Silver Cloud and S Type models swept away the existing owner-driver models and the first Continental, but the Silver Wraith remained available until 1959, typically for limousine coachwork. This is a 1957 car, with a touring limousine body by HJ Mulliner.

For the more distant future, the newly developed basic chassis and engine combination would also have to be capable of further development so that it could replace the Silver Wraith. In practice, it would do so in two stages: there would be long-wheelbase models of the standard car from 1957, and then a much larger and more expensive limousine chassis from 1959 that would become the Rolls-Royce Phantom V. At Crewe, there was no doubt that a new engine would have to replace the trusty 6-cylinder before too long, and in fact work on that had begun even before the new models began to reach their first customers.

HOW MANY WERE THERE?

By global industry standards, Rolls-Royce and Bentley cars were made in tiny numbers. None of that prevented the Bentley MkVI from becoming the most successful model to bear that marque name. Its production total of 5,201 between 1946 and 1952 equalled the total number of Bentleys made in the two decades before World War II.

The Bentley R Type, built for a much shorter time between 1952 and 1955, reached a total of 2,320 chassis, most of which carried the ‘standard steel’ body. On top of this, there were just 208 examples of the R Type Continental, which was built in the same period.

On the Rolls-Royce side, there were 1,783 Silver Wraith chassis between 1946 and 1959 (1,144 on the original wheelbase, and another 639 on the long wheelbase). The Silver Dawn remained quite rare, with a production total of 761 between 1949 and 1955. Rarer still was the 8-cylinder Rolls-Royce Phantom IV, of which just eighteen were made between 1950 and 1956.

CHAPTER TWO

DESIGN, DEVELOPMENT AND PROTOTYPES

Rolls-Royce began thinking about the car that would eventually replace the Bentley MkVI almost as soon as that car had entered production in 1946. The MkVI, or B-VI as it was known internally, was intended to have a very long production life in the Rolls-Royce tradition, but the plan was to give the company’s designers and engineers as long as possible to develop the replacement car thoroughly. There could be no question of cutting corners, and in the post-war world it was very likely that there would be some radical changes in customer expectations, and in motor-car design generally, before that new car reached the showrooms.

First thoughts on the eventual new car led to the creation of a number of prototypes that carried the internal designation B-VII. There were thoughts about two different sizes of car based on common components, the Rolls-Royce version being larger than the Bentley, but eventually the costs of such a programme began to look prohibitive, and by 1950 the company had resolved to focus on a single design that would be common to both Rolls-Royce and Bentley marques. It was known as the B-VIII.

Sir Henry Royce, the perfectionist engineer whose ideals remained intact at Crewe when the Silver Cloud and Bentley S Type were being developed. He died in 1933.

W.O. Bentley, the man who founded the Bentley marque in 1919. Bentley models had been developed alongside Rolls-Royce types since the early 1930s but were aimed at a different type of customer. It was always clear that there would have to be a Bentley version of the new car.

A key feature of this was that the passenger compartment should move forwards relative to the line of the rear axle. This would allow more room at the rear for a boot of decent size – which the production Bentley MkVI seriously lacked – but it would also require the engine and radiator to move forwards so that the passenger compartment should not lose any length. This was tried out on a rather crude prototype that would nowadays be called a ‘mule’. It had a modified MkVI chassis with the engine moved forwards, and a MkVI body suitably modified to fit behind it. The proportions of this car were all wrong from a visual perspective, but it was completed by February 1951 and proved the concept. It was known to the engineers as 10-B-VIII, the number indicating that it was the tenth post-war prototype and belonged to the B-VIII project.

The next stage was to build a prototype with a more realistic body design that reflected the name of ‘New Look’, which was already being given to the B-VIII concept. This was completed by September 1951, began testing in December, and was quite logically numbered 11-B-VIII. All the chassis elements so far intended were in place, and the body was designed around them and built by Park Ward, the ‘in-house’ coachbuilder that had been owned by Rolls-Royce since 1939. It was not a very distinguished design, following the latest trend towards flat sides with pressings in the panels to delineate the rear wings, but it did get the proportions right.

Both of these cars were used to try out enlarged versions of the existing B60 6-cylinder engine that was used in both the Bentley MkVI and the larger Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith. The production engines had a 3.5in bore and a swept volume of 4257cc (Rolls-Royce always worked in imperial measurements, even though the custom was to quote engine sizes to metric standards). The experimental engines included both a 4566cc size with a 3.625in bore and a 4887cc size with a 3.750in bore. Both would eventually enter production, the 4566cc size in 1952 and the 4887cc size in 1954. In view of the target date for the introduction of the new car, which was 1955, the larger 4.9-litre engine was slated for it.

Design and development work was centred on the Rolls-Royce works at Crewe, seen here in an aerial photograph.

Also in 1951 John Blatchley in the Styling Department at Crewe began work on a body design that would suit the new chassis proportions. The Bentley MkVI was the first Rolls-Royce product to have a standardized body design, an all-metal type whose manufacture was sub-contracted to Pressed Steel at Cowley. The plan was to design another standardized body for the forthcoming new model, and again to give the job of building it to Pressed Steel. However, the design of that body would be done by Rolls-Royce themselves.

Body styling was a function of the Experimental Department at Rolls-Royce, and Blatchley had joined that section in 1940. He had earlier shown precocious talent for car styling while a student, and became a protégé of A.F. McNeil at the coachbuilder Gurney Nutting. When McNeil moved to James Young, the twenty-three-year-old Blatchley took over from him at Gurney Nutting. He was an obvious choice to head the new Styling Department when it was formed at Crewe in September 1951, and when the Rolls-Royce Board rejected designs proposed for the forthcoming new car, he set to and within a week came up with one that met all their requirements. It was, and remains, a simply stunning achievement and one of the most attractive of all car shapes designed during the 1950s.

THE B-IX

Meanwhile, the ideas for the specification of the new car were developing, and the engineers had decided that they wanted an automatic gearbox in the specification. This would certainly have been because of the importance of the American market, where an automatic gearbox was becoming the sine qua non of luxury cars – and was also gaining ground fast in other types as well. Discussion had also led to a decision that a sophisticated heating and ventilating system would be needed, and the engineers were working on a design that would use vacuum-operated taps.

Both of these features were tested on prototype 11-B-VIII, but the car as a whole was no longer representative of the latest thinking. At Crewe, the programme was now renamed B-IX, and that name was in use by March 1952. However, B-IX was a short-lived phase, and the name seems to have fallen out of use by autumn 1952. In its place came a new codename that was associated with a much more clearly defined development programme. That new codename was Siam. It was a name put forwards by Harry Grylls, who had been appointed chief engineer of the Rolls-Royce car division in 1951. Grylls had worked his way up through the ranks in the company, having joined at the age of twenty-one in 1930, and Siam was to be the first major project he would oversee.

Harry Grylls was a long-standing Rolls-Royce employee who was appointed Chief Engineer of the car division in 1951. He made all the key decisions about the engineering of the new Silver Cloud and Bentley S Type.

THE SIAM PROJECT

All the new ideas that had been discussed over the last few years came together in Siam. Harry Grylls made the final decisions, and among the most important was that the new car would have a completely new chassis. This would be very much stiffer than the MkVI type, thanks to box-section side members instead of the open-channel type on the MkVI. It would have a longer wheelbase than the MkVI, the increment of 3in (7.5cm) allowing a more spacious passenger cabin; and it would have the new heating and ventilating system that was already on test. As for the engine, this was still intended to be the new 4887cc 6-cylinder that was under development, and it would drive the rear wheels through an automatic gearbox.

John Blatchley’s body design was handed over to Park Ward, the wholly owned coachbuilder that had by default become the Rolls-Royce experimental body division. Once a satisfactory shape and structure had been achieved, Pressed Steel would take over and bring it to production. The initial plan, drawn up under Harry Grylls, was to have six experimental or development cars with the proposed ‘standard’ saloon body, and to move on from there to test other variants as required later. These would include a high-performance Bentley Continental derivative, and later, a long-chassis limousine that would replace the current Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith. In practice there would be two limousine derivatives of Siam, the earlier being a long-wheelbase version of the standard car, and the later a larger prestige model called the Rolls-Royce Phantom V.

Chassis and mechanical development ran slightly ahead of body development, for fairly obvious reasons, and the first six Siam chassis were to be completed at Crewe over a period of about eighteen months. Park Ward, meanwhile, would have roughly two years to hand-build the six bodies destined for them. Overall, Rolls-Royce had about four years to bring Siam to production. It was a tall order for a car that had to inherit the mantle of the ‘best car in the world’ and remain worthy of it.

The first experimental body reached Crewe from the Park Ward works in autumn 1952, and was mounted to the first completed chassis. The first Siam car was built up with a Bentley radiator grille – which was a little less conspicuous than the Rolls-Royce type – and was allocated the experimental fleet number 20-B. Like so many experimental cars, it would go on to have a quite colourful life, and would be extensively rebuilt to test later Siam components, finally being scrapped in 1965 after thirteen years of use.

Surrounded by scale models used in creating the shapes of Rolls-Royce and Bentley cars, John Blatchley works with two model makers on the design of the Phantom V that would follow the Silver Cloud and S Type in 1959.

This car and the three that followed it during 1953 were primarily used for endurance testing, racking up high mileages under often deliberately adverse conditions to highlight weaknesses in the proposed specification. These were numbered sequentially as 21-B, 22-B and 23-B, and 22-B was notable as the only one of the Siam prototypes that was built with a Rolls-Royce grille. That inevitably required some minor alterations to the shape of the bonnet, and in production the differences that were developed here would remain right through until the last of the Siam family cars left the production lines in 1965. Like 20-B, all three of these development cars had the body shape that would be carried forwards to production.

The development programme was intense: by the time 22-B was completed in September 1953, all the major problems with Siam had been identified and were being or had been resolved. So by late 1953 the focus was largely on detail improvement. From April 1954, a fifth Siam prototype (numbered out of sequence as 25-B) joined the experimental fleet for more intensive work in the last twelve months before production had to begin in order to build up to a spring 1955 preview and a formal introduction in autumn that year. Although 25-B was built as a development car, it appears that it was also treated as a pre-production model – one that was very close to the final production specification.