1,82 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Charles River Editors

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

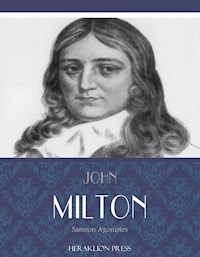

John Milton was an English poet and civil servant for the Commonwealth of England. Miltons poetry was heavily influenced by the political issues of his day. Miltons most famous poems are Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained. This version of Miltons Samson Agonistes includes a table of contents.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 71

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Samson Agonistes

Of that sort of Dramatic Poem which is call’d Tragedy.

TRAGEDY, as it was antiently compos’d, hath been ever held the gravest, moralest, and most profitable of all other Poems: therefore said by Aristotle to be of power by raising pity and fear, or terror, to purge the mind of those and such like passions, that is to temper and reduce them to just measure with a kind of delight, stirr’d up by reading or seeing those passions well imitated. Nor is Nature wanting in her own effects to make good his assertion: for so in Physic things of melancholic hue and quality are us’d against melancholy, sowr against sowr, salt to remove salt humours. Hence Philosophers and other gravest Writers, as Cicero, Plutarch and others, frequently cite out of Tragic Poets, both to adorn and illustrate thir discourse. The Apostle Paul himself thought it not unworthy to insert a verse of Euripides into the Text of Holy Scripture, I Cor. 15. 33. and Paraeus commenting on the Revelation, divides the whole Book as a Tragedy, into Acts distinguisht each by a Chorus of Heavenly Harpings and Song between. Heretofore Men in highest dignity have labour’d not a little to be thought able to compose a Tragedy. Of that honour Dionysius the elder was no less ambitious, then before of his attaining to the Tyranny. Augustus Caesar also had begun his Ajax, but unable to please his own judgment with what he had begun, left it unfinisht. Seneca the Philosopher is by some thought the Author of those Tragedies (at lest the best of them) that go under that name. Gregory Nazianzen a Father of the Church, thought it not unbeseeming the sanctity of his person to write a Tragedy which he entitl’d, Christ suffering. This is mention’d to vindicate Tragedy from the small esteem, or rather infamy, which in the account of many it undergoes at this day with other common Interludes; hap’ning through the Poets error of intermixing Comic stuff with Tragic sadness and gravity; or introducing trivial and vulgar persons, which by all judicious hath bin counted absurd; and brought in without discretion, corruptly to gratifie the people. And though antient Tragedy use no Prologue, yet using sometimes, in case of self defence, or explanation, that which Martial calls an Epistle; in behalf of this Tragedy coming forth after the antient manner, much different from what among us passes for best, thus much before-hand may be Epistl’d; that Chorus is here introduc’d after the Greek manner, not antient only but modern, and still in use among the Italians. In the modelling therefore of this Poem with good reason, the Antients and Italians are rather follow’d, as of much more authority and fame. The measure of Verse us’d in the Chorus is of all sorts, call’d by the Greeks Monostrophic, or rather Apolelymenon, without regard had to Strophe, Antistrophe or Epod, which were a kind of Stanza’s fram’d only for the Music, then us’d with the Chorus that sung; not essential to the Poem, and therefore not material; or being divided into Stanza’s or Pauses they may be call’d Allaeostropha. Division into Act and Scene referring chiefly to the Stage (to which this work never was intended) is here omitted.

It suffices if the whole Drama be found not produc’t beyond the fift Act, of the style and uniformitie, and that commonly call’d the Plot, whether intricate or explicit, which is nothing indeed but such oeconomy, or disposition of the fable as may stand best with verisimilitude and decorum; they only will best judge who are not unacquainted with Aeschulus, Sophocles, and Euripides, the three Tragic Poets unequall’d yet by any, and the best rule to all who endeavour to write Tragedy. The circumscription of time wherein the whole Drama begins and ends, is according to antient rule, and best example, within the space of 24 hours.

The Argument.

Samson made Captive, Blind, and now in the Prison at Gaza, there to labour as in a common work-house, on a Festival day, in the general cessation from labour, comes forth into the open Air, to a place nigh, somewhat retir’d there to sit a while and bemoan his condition. Where he happens at length to be visited by certain friends and equals of his tribe, which make the Chorus, who seek to comfort him what they can; then by his old Father Manoa, who endeavours the like, and withal tells him his purpose to procure his liberty by ransom; lastly, that this Feast was proclaim’d by the Philistins as a day of Thanksgiving for thir deliverance from the hands of Samson, which yet more troubles him. Manoa then departs to prosecute his endeavour with the Philistian Lords for Samson’s redemption; who in the mean while is visited by other persons; and lastly by a publick Officer to require coming to the Feast before the Lords and People, to play or shew his strength in thir presence; he at first refuses, dismissing the publick officer with absolute denyal to come; at length perswaded inwardly that this was from God, he yields to go along with him, who came now the second time with great threatnings to fetch him; the Chorus yet remaining on the place, Manoa returns full of joyful hope, to procure e’re long his Sons deliverance: in the midst of which discourse an Ebrew comes in haste confusedly at first; and afterward more distinctly relating the Catastrophe, what Samson had done to the Philistins, and by accident to himself; wherewith the Tragedy ends.

The Persons

Samson.

Manoa the father of Samson.

Dalila his wife.

Harapha of Gath.

Publick Officer.

Messenger.

Chorus of Danites

The Scene before the Prison in Gaza.

Samson: A little onward lend thy guiding hand

To these dark steps, a little further on;

For yonder bank hath choice of Sun or shade,

There I am wont to sit, when any chance

Relieves me from my task of servile toyl,

Daily in the common Prison else enjoyn’d me,

Where I a Prisoner chain’d, scarce freely draw

The air imprison’d also, close and damp,

Unwholsom draught: but here I feel amends,

The breath of Heav’n fresh-blowing, pure and sweet, 10

With day-spring born; here leave me to respire.

This day a solemn Feast the people hold

To Dagon thir Sea-Idol, and forbid

Laborious works, unwillingly this rest

Thir Superstition yields me; hence with leave

Retiring from the popular noise, I seek

This unfrequented place to find some ease,

Ease to the body some, none to the mind

From restless thoughts, that like a deadly swarm

Of Hornets arm’d, no sooner found alone, 20

But rush upon me thronging, and present

Times past, what once I was, and what am now.

O wherefore was my birth from Heaven foretold

Twice by an Angel, who at last in sight

Of both my Parents all in flames ascended

From off the Altar, where an Off’ring burn’d,

As in a fiery column charioting

His Godlike presence, and from some great act

Or benefit reveal’d to Abraham’s race?

Why was my breeding order’d and prescrib’d 30

As of a person separate to God,

Design’d for great exploits; if I must dye

Betray’d, Captiv’d, and both my Eyes put out,

Made of my Enemies the scorn and gaze;

To grind in Brazen Fetters under task

With this Heav’n-gifted strength? O glorious strength

Put to the labour of a Beast, debas’t

Lower then bondslave! Promise was that I

Should Israel from Philistian yoke deliver;

Ask for this great Deliverer now, and find him 40

Eyeless in Gaza at the Mill with slaves,

Himself in bonds under Philistian yoke;

Yet stay, let me not rashly call in doubt

Divine Prediction; what if all foretold

Had been fulfilld but through mine own default,

Whom have I to complain of but my self?

Who this high gift of strength committed to me,

In what part lodg’d, how easily bereft me,

Under the Seal of silence could not keep,

But weakly to a woman must reveal it 50

O’recome with importunity and tears.

O impotence of mind, in body strong!

But what is strength without a double share

Of wisdom, vast, unwieldy, burdensom,

Proudly secure, yet liable to fall

By weakest suttleties, not made to rule,

But to subserve where wisdom bears command.

God, when he gave me strength, to shew withal

How slight the gift was, hung it in my Hair.

But peace, I must not quarrel with the will 60

Of highest dispensation, which herein

Happ’ly had ends above my reach to know:

Suffices that to me strength is my bane,