9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

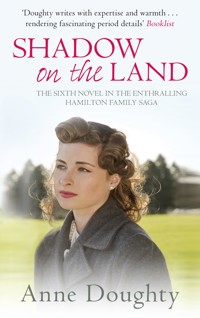

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: The Hamiltons Series

- Sprache: Englisch

It is 1942, and the Second World War has been going on for three wearying years. Work is hard in the Ulster mills in Northern Ireland where Alex Hamilton struggles to keep overworked machines going, just as his wife Emily tries to provide food and comfort not only for their own children, but for the many young American soldiers stationed nearby. Bad news comes daily, but there is still a welcome for friends and strangers, and moments of happiness come at even the darkest of times.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 453

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Shadow on the Land

ANNE DOUGHTY

For

Des Kenny of Galway who finds me books I never knew existed and sends my novels to Irish exiles

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

April 1942 Millbrook, County Down

Alex Hamilton closed the door of his office firmly behind him, strode along the short corridor to the main entrance of the tall building where he had spent most of the working day and stepped out into the freshness of the early evening. For a moment he paused, took a deep breath of the cool, rain-washed air, then ran his sharp, dark eyes around the wide expanse of tarmac stretched out between the brick cliff of the mill rising behind him and the curving access road that swept up the steep valley side to the main road beyond.

Even at this relatively late hour, there were two vehicles still loading. Bales and boxes stood piled high, as men in dungarees streaked with engine oil and lubricant lent a hand to the drivers and their helpers as they manhandled the bulky products. The spinning floors were running double shifts, working through the night, the only pause in the constant roar of their rotating spindles twelve hours on a Sunday to allow for essential maintenance.

Before he’d picked out Robert Anderson among the moving brown figures, Robert himself, the foreman of the evening shift, caught sight of him, raised a hand and moved briskly over to the elderly Austin which Alex was still permitted to use by virtue of the war work being carried out at all four mills.

‘We’re all set, Boss, if the worst happens,’ he said soberly as he came up to him.

‘Good man, Robert. I’ll come straight over if I hear anything, but if you get the signal ring anyway, just to be sure. Emily will tell you if I’m already on my way.’

Robert nodded, turned towards the half-loaded vehicle behind him, thought better of it and added, with a small awkward smile, ‘I hope ah won’t see you till the morra.’

Alex nodded, his heavy and sombre-looking face transformed as he responded warmly to the brave attempt at humour.

‘We live in hope, Robert, as they say in these parts,’ he replied, the softness of his speech reminding his long-time colleague that although Alex Hamilton had come from Canada long years ago, he had never lost his accent, nor his pleasure in the particular phrases and expressions of the place he had always called home.

The Austin was elderly, but had responded to Alex’s gift with machinery and his love of driving. It sailed up the slope with the greatest of ease. He whistled softly as he always did when he was quite alone, turned right on the empty road leading to Banbridge and passed briskly through the almost deserted streets. On the outskirts of the town, he took the road heading east in the direction of Katesbridge and Castlewellan, the Austin the only vehicle moving under a clearing sky patched with great expanses of blue between piled up towers of dazzling white cloud.

The days had lengthened and with the clocks now moved back to create Daylight Saving Time, the sun was still high. Here and there, it cast fingers of brilliant light into fields and hedgerows fresh with new growth, illuminating the palest of greens and turning them into an even softer shade of gold.

With long hours of work and little enough time to spend with his family, his drives were the one chance he had to look around him and observe the changes in the countryside he knew so well. They also gave him time to turn over in his mind the strange thoughts that had come out of nowhere, thoughts that now returned to him at any quiet moment of the day and haunted his dreams at night.

At fifty-three years old, or thereabouts, a long-married man with even the youngest of his four children soon to be eighteen, a responsible job as Technical Director of Bann Valley Mills, he never ceased to be amazed, that after all these years, he should suddenly begin to puzzle himself about his background. Why should he be at all concerned about his unknown parents and the circumstances which had left him, a child of five or six, an orphan on a ship bound for America.

Why now, he would ask himself. Why was it suddenly important that around fifty years ago his only possessions were the clothes he had been given and a label, a creased parcel label, attached with string to his coat collar, just where it rubbed and scratched his ear however much he tried to push it away.

‘Alex Hamilton,’ it said. That and nothing else. It was his entry ticket to an upbringing in institutions in Canada and the USA. It had led to his being placed, first, as a child worker and then as a farm labourer. Had it not been for broad shoulders and a robust constitution he would not have survived either the rigours of the orphanage regime or the beatings handed out by some of the men with whom he’d been sent to work. But he had survived. Long enough for a chance meeting with a Trade Union worker in an out-of-the-way place called German Township.

That whole episode was ridiculous when you came to think of it. The man’s name was McGinley, a friendly sort, well-educated, but not stand-offish. He had a shock of red hair, a soft Irish accent and his boots looked as if he’d recently been tramping across a piece of wet bottom land. After his address to the meeting on agricultural wages and conditions, he’d gone up to him to ask about membership of the union. When he’d given McGinley his name, he’d replied with a grin: ‘That’s a good Ulster name. I have a sister, Rose, married to a man called Hamilton. They live at a place called Annacramp, in County Armagh.’

Suddenly, he forgot the question he was going to put to him. It was as if he could think of nothing but this place in Ireland where there were Hamiltons. So he asked instead exactly whereabouts in County Armagh Annacramp was to be found. From that moment on, he had but one idea in his mind and that was how and when he was going to get there.

It was on a rough piece of road a short distance before he was due to turn up the steep slope of Rathdrum Hill that his eye caught sight of the waving needle on his dashboard. He stopped whistling abruptly, cursed quietly, and remembered the words of his old friend John Hamilton, the man who had once welcomed him as a member of his family purely on the set of his shoulders and his resemblance to his own father, Tom, who’d been a blacksmith.

‘I’ve changed and modified and improved every working part of hundreds of motors, but I’m damned if I’ve ever been able to make a fuel gauge more reliable,’ he’d declared. ‘The only safe way with fuel gauges, was to keep your tank topped up so that you never had to rely on the needle, unreliable even on the smoothest piece of road.’

Knowing John for the wise man he was, he’d always followed his advice, but things were very different now from how they were after the last war. Whatever petrol John needed for his continuous movement between the four mills, he’d simply to sign a chit at Bann Valley’s own pumps, which he might well pass several times a day. Nothing was that simple now with petrol so strictly rationed. Even when he had the necessary coupons from his entitlement, their authorised supplier in Banbridge might have nothing in his tanks to give him.

There was nothing to be done about his fuel supply between here and home beyond slowing down even further and avoiding having to stop on the hill. There should be a gallon can for such emergencies up against the stone wall at the furthest end of the workshop, kept well away from a chance spark from the metal cutter or the acetylene welder.

But he was still annoyed with himself as he scanned the road ahead. There was so much to think about these days, so many extra problems with the machinery running at full stretch, but when it came to the bit, that was no excuse. First things had to come first. What would he do tonight if he was needed and he had no car to collect the three extra men from Ballievy and get them over to Millbrook to join the others?

He slowed down rapidly as he picked up a distant roar of engines and pulled in as far as he could to his own side of the road, grateful there was a rough, grassy verge when it might just as well have been a water-filled ditch. Moments later, a convoy of Army lorries accelerated towards him. It was a regular hazard these days to meet these large and powerful vehicles on the narrow country roads. Often driven by inexperienced drivers, they roared past without reducing speed. Tonight, they were so close he could have touched their dark canvas covers without stretching out the hand that rested lightly on his open window.

He waved to the young men in camouflage as they passed, helmeted and carrying rifles. Smiles began to crease pale faces as they returned his greeting. English boys mostly. Yorks and Lancs was the name of this particular regiment, but according to his own son, Johnny, the rank and file were from all over the north of England, mostly the old industrial cities. No wonder they looked so uneasy when he saw them swing on ropes across the swollen waters of the Bann or found them in the field behind Rathdrum trying to navigate cross country with a pocket compass and a badly copied map.

Judging by the hour, it looked as if they might be heading north to Slieve Croob for a night manoeuvre. Often enough on his way to work he’d seen a convoy return in the morning, faces blackened, eyes listless with fatigue. But, of course, this lot might just be moving on. Troops came and went without any preliminaries. They arrived as strangers and were made welcome. Dances and socials were organised for them. They became friends. Then they went away. Sometimes one heard where they had gone and how the regiment had fared, but, whether things went well or badly for them, they seldom came back.

He sounded his horn and waved at wee Daisy Cook, who sat on the wall of Jackson’s farm, her arm round a sheepdog puppy. It had been Cook’s farm for years now, but for him it would always be Jackson’s, the farm at the foot of the hill where he’d boarded when he’d first arrived back from Canada, visited John and Rose Hamilton at Ballydown and been taken on by John as his assistant at the four mills. It was at Jackson’s farm he’d met Emily, an orphan like himself, living with her aunt and uncle.

Tonight as he tooted and waved to Daisy, he thought of the April night he’d driven his good friend Sarah Sinton and her children back home from Dublin after the Easter Rising. He and Sam Hamilton, Sarah’s brother, had gone down together in two motors when they’d heard the railway lines had been dug up north of Dublin and Sarah would have no means of returning. Emily had been so anxious about his going. She said she’d be waiting up till she heard the motor going past on the way up to Ballydown, no matter how late it was.

He pressed gently on the accelerator and built up his speed. With any luck, he could take a smooth line up the steepest part of the hill without meeting one of the heavy lorries from the newly-opened quarry beyond Rathdrum. They weren’t supposed to come down this way because of the steepness of the road, but following the new quarry road north to the main road did make their journey longer if the crushed rock was hardcore for one of the many new airstrips being built in the south of the county.

The only sign of life on the long, steep hill was a bicycle parked against the garden wall of the farmhouse at Ballydown where Emily and Alex had made their first home after Rose and John moved up to Rathdrum House itself. Danny Ferguson, the new mill manager at Ballievy, would be down the hill in minutes if the signal went up.

He caught a glimpse of pink blossom as he moved steadily past. He wondered if it was Rose’s camellia, the one she and John had cherished for all the years they had lived there, planting a garden from scraps and cuttings Rose had brought from her very first garden, back in Annacramp in County Armagh.

As he crested the hill and prepared to swing under the trees into the avenue leading to Rathdrum House, Alex was amazed to catch sight of a lorry parked closely against the hedge on the down slope some way beyond his own entrance, the tarpaulins that had covered its load neatly folded and roped down.

Even before he caught sight of the tailboard and read the familiar name, his face lit up. As he expected, it read: Fruitfield Jams and Preserves. He knew only one man who could park a lorry that close and that straight.

‘Sam Hamilton. You’re a stranger. How are you, man? It’s great to see you,’ he said, beaming, as he stopped the Austin in the cobbled yard at the back of his house and shook hands with the tall, broad-shouldered figure who’d hurried out into the yard to meet him when he’d caught the first throb of the vehicle on the road up the hill.

‘Great to see you too, Alex,’ replied Sam, grasping his hand firmly. ‘Emily’s been givin’ me all your news, but she was afraid ye might not get back before I hafta to go.’

‘Ach Sam, can ye not stay a while?’ Alex asked, his face clouding.

‘I can stay a wee bit longer,’ Sam replied, reassuringly, ‘but I hafta get back in daylight. This blackout is a desperit thing. No matter how careful ye wou’d be, ye can see so little with these masked headlamps. An’ sure a lorry like mine cou’d kill half a dozen soldiers if they’re on manoeuvres and had no white markers.’

Alex nodded sadly.

‘You’re right there,’ he agreed. ‘We’ve had so many accidents round here lately. And not just the blackout. With all these Army vehicles we’ve had some bad ones in daylight as well. There were four roadmen having their tea thrown into the hedge this time last year. None killed, thank goodness, but two of them left in a bad way for quite a while. People are just not used to this sort of fast traffic at all hours of the day and night. Their reactions are too slow.’

They moved together towards the back door where Emily stood watching them.

‘Alex dear, there’s some dinner in the oven, but I must go down to Cook’s now you’re home. Johnny was in for his tea earlier and we’ve no milk for the morning,’ she explained with a wry laugh. ‘I’ve just made you a pot of tea and left you some cake,’ she added, as she picked up her shopping bag and set off.

‘Has Emily given you your supper, Sam?’ Alex asked, as he picked up the tray she’d left and led the way to the sitting-room where a bright fire burnt on the hearth.

‘No. Your good Emily offered me my supper the minute I set foot in the house, as Emily always does,’ he replied warmly, ‘but I was given a meal at Chinauley House when I delivered to them. Guest of the King’s Own Rifles,’ he added smiling. ‘An’ very good it was too. They said on their wee menu that it was chicken, but if I know anything it was rabbit. Aye and none the worse for that,’ he added vigorously, as Alex handed him a mug of tea.

‘There’s a great warren just across the road from that big house,’ he went on. ‘The Nut Bank, it used to be called when I was a wee boy. They’ve a pontoon bridge across the river and it’s a rifle range now. Bad luck on the rabbits,’ he added sharply.

Alex laughed.

‘Bad luck on us all, Sam. One man’s wicked ambition that leaves poor people frightened out of their wits and half-starved and even kills the rabbits.’

‘Aye, given how bad things are we’ve a lot to be grateful for and only the one loss so far in our family. I can’t remember if I wrote to you about it,’ he said cautiously. ‘Sure it’s well over a year since I got the chance to come over,’ he said, breaking off, as he saw the anxious concern creep over Alex’s face.

Alex shook his head slowly and waited.

‘Ach dear. Well it was the Belfast Blitz. The big one on Easter Tuesday. A desperit business altogether. Young Sam’s wife, wee Ellie, had her cousin Tommy Magowan killed. It seems he was fire-watching in place of a friend of his when his parents thought he was away in Bangor with his girlfriend. It was only when he didn’t come home they began to worry. His father found him in St George’s Market the next morning, laid out with all the rest of the unidentified casualties. Not a mark on him. They said it was blast that killed him.’

Alex dropped his eyes from Sam’s candid gaze, the images of that night now springing up as brightly as the flaming, onion-shaped incendiaries that had rained down on the city.

‘Do you remember, Sam, when the last war came and the two of us sat in your workshop trying to decide what we’d do if there was conscription?’ Alex asked, as the silence lengthened between them.

‘Aye. I think we decided we could maybe get into an Ambulance Corps together, neither of us having any wish to kill our fellow men.’

Alex nodded slowly and stared into the red embers of the wood fire.

‘Sam, I was in Belfast that night and I don’t think I’ll ever be able to forget it,’ he confessed quietly.

‘Man dear, how did that come about?’ Sam asked, his eyes dilating with the shock of Alex’s words. ‘Were you there when it started, or what happened at all?’

For weeks after that night, Alex had thought of writing to tell Sam of his night in the burning city, but he’d not been able to face it. They’d been friends for so long and had always told each other the truth, even when it was not to their credit, but the thought of words on the page had been too much for him. So he’d said how busy he was and let Emily write the short notes they’d always used to keep in touch, two or three times a year and a longer one at Christmas. But now he’d have to make up for his evasion.

‘Emily and I had just gone to bed when I heard a noise,’ he began, easily enough. ‘Couldn’t place it at all. A vibration. Not thunder, but getting louder. I got up and went outside. It was full moonlight but I couldn’t see anything to the south with the way our trees have grown up. What I could feel was the air moving. And there was a smell. I can’t describe that smell, but suddenly I knew it was bombers and there must be hundreds of them to make the air move like that. So I went in and phoned the mill managers. By the time I got down to Ballievy, Harry Creswell who lives on a hill beyond Seapatrick had seen the incendiaries falling. He said they were coming down so fast it was like one of those pictures of Hell you’d see in these evangelical tracts people put through doors.’

Alex paused for breath and finished his mug of tea.

‘We’re well organised for fire in the mills. We have to be, as you know,’ he began again, his voice still steady, ‘but the turn out that night was a credit, though I say it myself. The four engines, fully-manned were on their way in no time.’

He stopped, shook his head and dropped his face in his hands. When he looked up again his eyes were full of tears.

‘Sam, you might as well have taken a child’s bucket and spade as our four engines. The place was an inferno, the fires beyond anything any of us had ever seen, and when we did get into the city there was no water pressure. They’d bombed the reservoir and the water mains were gone. Even where there was a fire point still standing our hoses didn’t fit.’

‘Ach man dear, I’d no idea you were in Belfast,’ Sam said, his face suddenly looking old and lined as he recalled that night himself. ‘Sure we heard what was happening from the guard on the last train up. He told the Stationmaster at Richhill and he walked over to the farm and told us. Apparently the train was leaving Belfast just as it started. Our Jack went up to Cannon Hill to tell the Home Guard patrol up there, but he didn’t have to tell them for you could see it from up there, the whole city on fire, the sky for miles around lit up with the flames. He said when he came back about all we could do was pray for the poor souls.’

Sam looked down at his hands. They were broad, thick-fingered hands, not the kind you would think best-suited to make the fine adjustments that were such a part of his everyday work.

‘So what did you do when you couldn’t fight the fires?’

‘We got out the spades and the tackle and started digging people out of wrecked houses. And we brought a few out alive from under the stairs. But most were dead. Some of those poor wee houses wouldn’t give shelter to a mouse. Those people in the government up at Stormont have a lot to answer for,’ he went on bitterly. ‘I’d heard it said they spent more time in Cabinet discussing how to protect that statue of Carson they’re so proud off than protecting the people of Belfast. I saw for myself that night. It was absolutely true.’

‘Aye, I’m afeerd yer right about the Government. I’ve seen m’brother James a few times recently. He’s still in Economic Development, but he says there’s no go in them at all, bar one or two labour or socialists like Tommy Henderson and Harry Midgley. Sure, they only meet now and again for a couple of hours when there’s so much they could be doin’ to help people. I think James would resign, but then he knows that wou’d only make it worse. At least in his Department he can do somethin’… Maybe, Alex, all we can ever do is somethin’. Who knows what value any action of any one of us, however small, might be. It could be far more important than we could ever imagine. We must live in hope, man, and with God’s help we’ll come through,’ he said strongly.

Alex had never found any reason to expect God to help him or anyone else, even if He did exist, but then he had always recognised that Sam’s God was a different matter. Now in his late fifties, Sam had become a Quaker many years earlier. He’d practised his religion quietly and firmly and now had a steadiness and assuredness about him that Alex found quite enviable.

‘You’re right, Sam. We can only do our best. I only hope that best will be good enough,’ he said honestly, looking up at his friend as he watched him get to his feet.

The bright April evening was paling towards dusk and shadows were lengthening in the fire-lit sitting-room. Although the journey was only some fifteen miles, Alex knew well the possibility of a delay if a convoy was moving somewhere between Banbridge and Richhill.

They walked down the avenue together, the fresh foliage above their heads now fluttering in a small, evening breeze, long fingers of light spilling across their path as the sun dropped to the horizon.

‘I mind Sarah and Hugh planting these two trees here after a big storm,’ Sam said suddenly, looking up into the interlacing branches as they tramped along together. ‘That must have been a couple of years before Hugh died and you arrived back from Canada. And I mind too, you and young Hugh down there on the hill planting out wee oaks he grew from acorns,’ he added, as they came through the gates and gazed down the hill at the mature trees which stood in the hedgerow opposite the single house on the right-hand side of the road, the well-loved home they had both known, Sam as a child, Alex as a young married man.

‘Great oaks from little acorns grow. Isn’t that one of the saying in these parts?’ Alex asked.

‘Aye, and your wee friend Hugh Sinton is doing great work down on Lough Erne I’m told. James had to go to Enniskillen on business and went to see him. He’s moved there to test out some new plane he’d been working on at Shorts in Belfast. Sarah could only drop me hints in her last letter, but James told me it’s to do with spotter planes. Give the same man a while longer, he said, and we’ll not be losing all this shipping to the U-boats.’

They stopped by Sam’s lorry and Alex asked the question that had been in his mind since the moment he’d seen it.

‘Are you short-staffed at Fruitfield?’

‘No, thank goodness, we’re not. Most of us are too old to join up. It’s mainly the girls from the office that have gone, so our Jack tells me. Why d’ye ask?’

‘Well, I was wondering why the senior man who keeps the whole place running was out delivering jam.’

‘Ach, now I see what yer gettin’ at,’ replied Sam, laughing. ‘Sure I don’t mind the odd wee run out. It’s Security. If you deliver to the forces, you have to be cleared. They wouldn’t let a couple of young fellas anywhere near Chinauley House or the Gough Barracks in Armagh or anywhere else where there’s troops for that matter. It’s the same with delivering war materials. Shell-Mex in Armagh have only the one man allowed to deliver petrol. They have to be certain they’re trustworthy. Sure there’s a black market in everything.’

‘Well, they couldn’t pick a straighter man than you, that’s for sure,’ said Alex, now laughing himself, as Sam swung himself up into the cab.

‘Except perhaps yourself,’ Sam came back at him promptly. ‘Let me know how things go with the girls and young Johnny and I’ll maybe get another chance to come over in another month or two when they’ve eaten what I brought today. God Bless,’ he added, as he raised a hand in farewell.

Alex watched him move down the longer, gentler slope towards the main road, the noise of the batcher at the quarry now loud on the evening air. Breeze blocks for building. Crushed rock for hard standing. Gravel for mending overburdened roads. The quarry was working all the daylight hours, the dust from the crushers throwing a white mist over the nearby hedgerows until the next heavy shower came to rinse the foliage and leave it shining again.

He turned away as the lorry became a small moving object in the green landscape and walked back up towards his own gates, his stomach rumbling vigorously, reminding him of his supper in the oven.

The sun had gone now, down behind the low hill at Lisnaree, but there was still quite enough light to see two figures walking up towards him. One was clearly Emily. Beside her, carrying her shopping bag from which came the small chink of milk bottles, there was a man he did not recognise. From this distance, he could not even guess whether he was a friend or a stranger.

CHAPTER TWO

There was no doubt there was something familiar about the figure that moved easily up the hill, matching his pace to Emily’s shorter stride. A man about his own height, but carrying more weight, comfortably dressed in a tweed overcoat and a soft cap. He was talking so animatedly that it was only when Emily interrupted him by the gates of Rathdrum he realized Alex was standing there waiting to greet him.

‘Isn’t it lovely to see Brendan again,’ said Emily helpfully, assuming that Alex would never remember his name after so many years and so few previous meetings.

But Alex surprised her.

‘Brendan Doherty, you’re welcome,’ he said with a broad smile. ‘We haven’t seen you for many a long day. I’m afraid it was your Aunt Rose’s funeral when we last met and that must be seven years ago. What brings you up to the North?’

‘Well I haven’t come to spy, though there’s those looked distinctly dubious when they heard my Southern accent,’ he said with a wry smile. ‘Believe it or not, there are still books to be bought and sold, especially where the owners are handing over their houses to the military. Though on this occasion it was maps. Sixteenth century, I hasten to add, as I was just explaining to Emily. I didn’t dare mention the word “map” in the hotel in case I ended up in jail, so I told a lie and said “books” instead.’

‘Is it as bad as that?’ asked Alex as they rounded the house and came in through the kitchen door.

‘Oh dear, yes. The North can’t forgive de Valera for remaining neutral. Churchill goes on at length about the loss of the Treaty ports and some of the Northern papers are saying there’s a thousand or more German spies in the South and they’ve brought dozens more into the Legation in Dublin.’

‘And have they?’ asked Emily solemnly, as she took her shopping bag from him and put the milk bottles in their bowls of water in the larder.

‘At the last count, six staff, three typists and an old fellow to look after the boiler,’ he replied, his dark eyes twinkling.

Alex laughed and led their guest through the kitchen and into the hall.

‘Now Alex,’ said Emily firmly, as she hung up her coat and reached out her hand for Brendan’s, ‘have you had your supper?’

‘No, not yet,’ he said quietly. ‘But what about Brendan’s supper?

Brendan laughed.

‘The hospitality of the Hamilton’s is legendary, as I have no doubt told you on one of our rare meetings, but I have indeed been fed. Your local hostelry couldn’t give me a bed, they being full of officers having a conference about gas, the poisonous sort, not the domestic variety. But good Ulster folk as they were, they wouldn’t turn me away hungry. I had a rather good chicken casserole with plenty of vegetables and more milk to drink than I’ve seen in months. At least, I think it was chicken. It’s a long time since I met chicken on my plate.’

Emily wondered why Alex smiled suddenly, but the moment passed as she led them into the sitting room, added another log to the fire and told Alex why Brendan had not been able to go straight back to Dublin as he usually did after one of his buying trips across the border.

‘An Army lorry clipped his car,’ she explained. ‘Wasn’t he lucky they didn’t run him off the road?’

‘They were pretty decent about it,’ Brendan added quickly. ‘At least they stopped and sent two squaddies to help me get the car to the garage. And by further good luck the garage was only down the road so I just watched the pair of them push. But I’ve lost a headlamp and the wing mirror and have a big dent in the offside. There’s a leak too by the smell of it. Couldn’t risk driving her till she’s checked out.’

‘I didn’t fancy sleeping in a ditch,’ he went on cheerfully, ‘though I’ve done it in my time. So I set out for Ballydown. The Cooks were just telling me you’d moved up in the world when Emily herself appeared. I said a blanket on the sofa would have done but your good lady says I have a choice of rooms with all the girls gone,’ Brendan continued, addressing himself to Alex, as he stretched out comfortably, his legs directed towards the leaping flames.

At that moment the telephone rang in the hall.

Alex was on his feet and out of the room before Emily or Brendan had registered the first strident ring.

‘Oh dear,’ said Emily, her face dropping. ‘If that’s what I think it is, it’s bad news and Alex will have to go off right away.’

‘Are ye expecting bad news?’ Brendan asked soberly.

‘It’s nearly the full moon,’ she said quickly. ‘That’s when we had the awful blitz in Belfast last year. There’s been rumours going round that they’ll have another go because the aircraft factory and the shipyard are more or less back to normal working. I don’t know whether Lord Haw Haw said something on the wireless, for I refuse to listen to him, or where the idea came from, but Alex is responsible for the four fire engines and he was told to stand by.’

‘Aye, that was a bad go ye had last year,’ said Brendan, his lively, mobile face subsiding into a solemn mask. ‘At least de Valera had the decency to send the fire engines up to help. We heard some grim stories in Dublin when they got back …’

He broke off as they heard the door open behind them. Alex moved quickly across to the fireplace, his face transformed, relief and joy bringing a sparkle to his dark eyes and softening a face that had always had a sombreness built in to it.

‘It’s all right,’ he said quickly, a slight catch in his voice. ‘We’ve been told to stand down. No details and we don’t even know who sent the message, only that the code was right. If they’d been coming this far, they’d have taken off from France by now and been picked up on the south coast of England.’

‘Maybe now you’ll eat your supper,’ Emily said, standing up. ‘You’ll drink a cup of tea, Brendan, won’t you and we’ll keep him company with a piece of cake.’

‘That would be most welcome, Emily. I’m just sorry I’m not provided with the traditional bottle. I fear I’ve come with one hand as long as the other.’

Alex laughed delightedly. It was an expression he’d hadn’t heard for ages, one he’d never forget. Emily had had to explain it to him, long years ago, when she was no more than a schoolgirl and he still the lodger, only recently returned from Canada.

‘Sure we’re all empty-handed these days, Brendan,’ she said, pausing by the door, ‘as far as bottles go anyhow. We try to keep up a bit of hospitality for these young lads billeted all round the place, but I’m afraid tea and cake is the best we can do. You could count the raisins in my cakes these days. Few and far between, as they say.’

Alex was grateful for the covered plate Emily brought him from the oven. She was a good cook and he always enjoyed what she gave him, but tonight even bread and margarine would taste wonderful. However little meat in the pie, the rich gravy was appetising and he dug into the mound of creamy potato with vigour. Brendan watched him with pleasure and a certain twinkle of amusement.

‘As I said earlier, Emily,’ he began, as she handed him a cup of tea and a generous slice of cake, ‘the Hamilton hospitality is legendary. Did Alex ever tell you about my visit to his friend Sarah Sinton when she was unavoidably detained in Dublin during The Rising.’

‘No, I don’t think I ever heard that one,’ said Emily cautiously.

Alex grinned broadly as he finished his meal and wiped his plate clean with a fresh crust of bread.

‘I’m afraid Brendan, Emily and I had a slight difficulty at that time over my relationship with Sarah.’

‘Oh,’ said their visitor, ‘is that so?’

His eyes sparkled as they moved rapidly from husband to wife.

Alex grinned and glanced across at Emily who was now smiling too.

‘You see, Brendan,’ Alex began, ‘when I first came to Ballydown, Sarah was a very handsome young widow. Not that I noticed what she looked like. The fact was, she was kind to me. She understood how I felt about not knowing who I was or where I’d come from. And she was sad and lonely herself. She said that without Hugh she didn’t think she could go on running the mills. She couldn’t stand the bitterness between Catholics and Protestants and the labour troubles and people never willing to listen to the other side of the story. So, to cut a long story short, as they say around here, Sarah and I made a pact to help each other and I made up my mind I’d not marry till Sarah herself married or went away.’

‘And what happened?’ said Brendan slowly.

‘Well, you probably know that Sarah met Simon Hadleigh when she was over in Gloucestershire visiting Hannah and Teddy. She’d actually met him years earlier at their wedding when Hannah asked her to take the wedding pictures, but as she told me once, she was so busy photographing her sister and new brother-in-law that she’d not even noticed him. However, as soon as Sarah and Simon were engaged, I made up my mind about Emily. But I didn’t say anything to her. Then, that Easter of 1916 when Sarah was in Dublin, Simon goes missing. He’d been in St Petersburg, in the diplomatic service,’ he added quickly, when he saw Brendan looking puzzled.

‘Anyhow, he was coming home from Russia on a Swedish packet and it hit a mine near the Dogger Bank. Luckily, he was picked up by a destroyer but because it was a destroyer he couldn’t send her a message. There wasn’t a word from him for weeks until finally the destroyer was able to land him in Scotland. Sarah was beside herself. I was with her when the telegram came to say he was safe. I knew then she’d go over and marry him as soon as she could, so I came and proposed to Emily.’

‘And Emily was furious,’ said the lady herself, laughing. ‘I thought Sarah was the woman he wanted and now she was going away to marry Simon, I was second best. So I told him to go and jump in Corbet Lough.’

‘Ah, women,’ said Brendan raising his eyes to the delicate mouldings on the ceiling, ‘Is it any wonder I never took the plunge.’

Working away at the sink next morning, her fingers already rippled with the continuous immersion and the scrubbing of Alex’s dungarees, Emily thought what a splendid evening they’d had. It had been so lively and so completely unexpected. She hadn’t seen Alex laugh as much for months. But then there was very little to laugh at these days. Just bad news and more bad news.

There was no doubt Brendan was a talker, but if he was, everything he said was interesting, whether he was commenting sharply on the political situation in the North or in the South and the tensions between their respective populations, or simply recalling stories from family history. Emily could see from his detailed accounts that he missed nothing in his observation of people. She also felt she’d learnt a great deal more from him about what they called The Emergency in the South than she’d gained from her perusal of all the newspapers she could lay hands on here in the North.

Now the house was silent again, as it was so often these days. Alex had taken Brendan to the garage on his own way to work, Johnny had come in, eaten his breakfast and gone to bed, exhausted from his night’s work, fire-watching at a local factory. Apart from the tick of the kitchen clock, the only sound she could hear was the song of a blackbird, perched on the roof of the workshop across the yard where he sang every morning regardless of weather or the affairs of men.

A pleasant-faced woman, now almost fifty, her dark curly hair already streaked with grey, Emily had worked hard all her life. Physically strong and always active, she had kept her figure and still dressed as well as she could. There was enough to depress everybody these days without her going round looking colourless and unkempt.

She had, ‘hands for anything’ as the Ulster saying has it. She was never without an item of knitting, for Alex, or Johnny, or her Red Cross collection. There was usually sewing as well, a dress or a blouse for one of the girls, the pinned pattern, or the work in progress, laid out in pieces on the bed in one of the now silent bedrooms.

But beyond her family, her beloved garden and her considerable domestic skills, Emily’s great passion was reading. Though Alex scolded her for not sitting down until her back actually ached, she did spend time every day with her library book. No print of any kind that entered the house escaped her eye, be it newspaper, magazine or church newsletter. In the days when her four children were at Banbridge Academy Emily would be been found reading not only the set books for English Literature but all their text books as well.

Given this passion, it was hardly surprising that a friendship should have developed between Emily and Brendan Doherty. It had begun on the lovely summer Sunday of Rose Hamilton’s eightieth birthday party. Arriving early and walking round the garden of James Hamilton’s house in Belfast, while Alex gave a hand with some extra seating, she’d found Brendan sitting in a quiet corner reading while waiting for the other guests to arrive. They had talked about books and bookselling, taken to each other immediately and made a point of finding each other again after lunch to sit in a corner of the huge marquee erected over the back garden and continue their conversation.

She had met Brendan briefly on previous occasions when he’d visited his Aunt Rose at Rathdrum, but she’d never talked to him at any length and certainly not about books. To tell the truth, she’d been rather shy of him. Not only was he rather handsome, but she knew quite a bit about his history from Rose. She wasn’t sure what you could say to a young man who’d been a rebel, had fought against the British Army and spent years in English jails mixing with other rebels even better known than himself.

Rose had always been fond of the young man, the youngest son of her eldest sister Mary, who’d found a job with the Stewart family of Ards when the McGinley family had been evicted from their home in Donegal back in the 1860s. She’d married a local man and raised a large family on the outskirts of Creeslough where he had a flourishing drapery business, while her little sister Rose had been taken to Kerry with baby Sam when their father died and her mother found work there as a housekeeper with the Molyneux’s of Currane Lodge.

Emily still missed Rose. For the years of Emily’s girlhood, Mrs Hamilton, as she then called her, had been their neighbour and her friend. She’d seen her nearly every day, taking up eggs or milk, or making tea when she came down to visit the Jacksons at the bottom of the hill. Rose had always been good to her, lent her books and knitting patterns and was always willing to listen to her troubles. When she and Alex married, it was Rose who suggested they should move into her house at Ballydown now that she and John were going to live at Rathdrum.

No mother could have been kinder than Rose when she was first expecting and full of anxiety, nor when the babies were growing up and she worried continually as to whether she was doing the right thing by them. Rose had been with her when all the girls were born. She could hardly bear to think of the day Rose had not been there, the day young Johnny finally appeared after the longest and hardest labour she had ever had. That was the day Rose’s beloved John had died, only a few hours after Alex had gone up the hill to tell him the longed-for boy had arrived at Ballydown and that his name would be John.

Emily wiped away her tears with a soapy hand and told herself not to be silly. It was all a very long time ago. Eighteen years ago, come August. She could not possibly forget the day, or the date, or the year, not only because it was her son’s birthday, but because this year in August he’d be eighteen, old enough to do what he so wanted to do and join the Air Force, like his sister Elizabeth. Then she would be like mothers everywhere, living with the fear of his loss as every day went by.

As if to escape from her anxious thoughts, she pounded the dungarees more vigorously, drained off the dirty water and began rinsing them. When she splashed herself thoroughly with the ice cold water from the tank on the roof, she knew she just wasn’t paying proper attention to the task in hand, so she collected herself, dumped the wet, brown mass into a bucket and tramped out to the already laden clothesline.

She wondered why it was she was never as anxious about the girls as she was about Johnny. It was not that she loved them any the less, but they always seemed better able to take care of themselves than their brother. There was a casualness about him, an indifference to circumstances quite different from either of the two older girls, who had always been much more practical. More like herself perhaps. At present, however, the main reason she didn’t worry about them was that all three of them were fairly well out of harm’s way, for the moment at least.

Catherine, the eldest, had trained as a teacher, gone on a course in Manchester to learn more about children with writing difficulties and had met a young research chemist at a dance. She’d returned home, gone on teaching at a local primary school and they’d written to each other, enough pages to fill a book, in the following year. Being quite sure by then that war was coming, they’d decided to marry regardless.

Brian Heald had expected to be called up, but to his surprise when he applied himself, he was told he was to be reserved because of his qualifications as a chemist. He’d been sent to a laboratory recently relocated in the countryside south of Manchester. Catherine had found a job in a village school and a half-derelict farm cottage for them to live in.

Elizabeth was nearly two years younger than Catherine and probably even brighter. But Lizzie, as almost everyone called her, had no wish to train as nurse or teacher, the only two options her teachers appeared able and willing to approve. She wanted to travel, to see faraway places and meet new people. The recruiting poster for the WRAF could have been designed especially for her, even down to the blue eyes that looked so well with the uniform. She made up her mind to join. She’d applied, was accepted, and then tried to get a job with the Meteorological Service in Bedfordshire. With very good school results, particularly in geography, she might well have got what she wanted had it not been for a sudden prior need in Belfast.

To Emily’s enormous relief, after a period of concentrated training, she was posted as a plotter to the Senate Chamber at Stormont, an impressive marble clad chamber which had been handed over to the War Ministry for use as an operational centre for the duration.

Not only was the formerly large and conspicuous Stormont building well camouflaged, but as more than one person had put it, there was no need for Hitler to bomb it, for no one would ever notice the difference.

It was a bitter comment on an unpopular and inactive government, but it cheered Emily to know that her daughter’s work kept her well away from any of the obvious enemy targets and that the girls’ billets were right out on the edge of the city. There was also the wonderful bonus that occasionally, without any warning, Lizzie herself would appear at the back door, yawning from lack of sleep, grinning from ear to ear and saying, ‘Hello, Ma, I’m home. Thirty-six hours. Can you stand it?’

Which left Jane.

Emily had never understood why Alex had wanted to call their third daughter, Jane. With both the other babies he’d discussed names with her and they had no difficulty coming to a decision together. Catherine was named for Emily’s own, long-dead mother, Elizabeth for the aunt who had given her a home when her mother died. Any boy they ever had was going to be called John. But Emily could see neither rhyme nor reason behind Alex’s wanting to call their third girl, Jane.

‘They’ll call her Plain Jane at school, Alex,’ she had argued, when it was time to make the final decision.

‘No,’ he said firmly. ‘Jane it has to be. Besides that child will never be plain in any way.’

She had to admit he’d most likely be proved right, for little Jane had been a particularly lovely baby, full of smiles and blessed with great blue eyes that captivated everyone who saw her. Apart from being the prettiest of his daughters, Jane was the sweetest in nature. Soft-hearted to a fault, generous of spirit and possessed of a formidable patience, she seemed to sail through life oblivious to its dark side, protected by an unfailing sense of hope and possibility.

If ever Alex was downcast, overburdened by the job, or the endless labour problems that had dogged the industry between the wars, then it was Jane who was able to cheer him. It had taken Emily a long time to realize that having a son had been Alex’s passionate desire, but it was his youngest daughter who understood him in a way that Johnny never would or could.

It was no surprise to anyone when Jane announced she wanted to be a nurse. She’d been looking after other children since she was old enough to go to school. She’d learnt to apply sticking plaster effectively long before her elder sisters. Nor was it simply cut fingers and grazed knees that Jane would wash and dress. Whatever hurt or damaged creature she laid eyes on, found in the garden or by the roadside, she couldn’t rest till it had been cared for. Emily remembered well the times when she was afraid to move in her own kitchen, so cluttered was it with cardboard boxes holding small creatures parked in different places.

The Royal Victoria Hospital might not have been as safe as the Senate Chamber up at Stormont, but it was a hospital, and in the early days of the war it still seemed to Emily that it would not be bombed. At least the authorities had made provision for the protection of its staff when off duty.

Suddenly and unexpectedly, the April sun emerged from behind a cloud, throwing shadows on the grass path. It’s sudden warmth caressed Emily across the shoulders which ached as always after the morning’s washing. She stood for a few moments enjoying the comfort it brought.

‘I’ll just take another five minutes outside,’ she said aloud, as she moved away from the vegetable garden where her clothesline was now full, the dungarees dripping vigorously.

She moved back towards the house and turned into the flower garden. Drifts of daffodils and crocuses splashed colour against a background of shrubs and trees and enlivened the still-bare earth of flowerbeds where perennials were just beginning to throw out rosettes of new growth.

She walked quickly to the end of the path to the one remaining space between the sheltering trees from where she could see the mountains. This had once been Rose’s favourite place, the place Emily was sure to find her if she came to see her and found the kitchen empty.

As great spotlights of sunshine fell on the high, sombre peaks and spilt downwards to light up the patchwork of small fields and the occasional white-painted cottage on the lower slopes below, she saw why Rose loved this prospect so much, but for herself, the familiar prospect brought a kind of sadness. What Emily longed for was the sea. The Mountains of Mourne did indeed sweep down to the sea, as the song had it, but that vast, blue expanse which brought her both joy and longing, filled as it was with memories of childhood in one Coastguard Station after another, was beyond the mountains, completely hidden from this perspective.