9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: The Hamiltons Series

- Sprache: Englisch

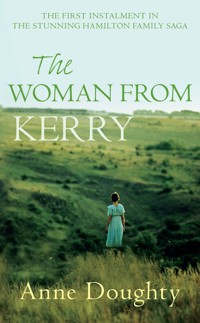

Little Rose McGinley is just seven years old when her family is harshly evicted from their home in Donegal, victims of the Clearances of 1861. It is the first step in what will be a long and eventful journey for Rose, one that will take her from Donegal to Kerry, and back again to the North, with her husband and four children.But the feisty little girl blossoms into a woman of extraordinary character, who confronts hardship and tragedy - as well as great happiness - with steadfast courage and the determination to keep her family together, against all the odds.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 550

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

The Woman from Kerry

ANNE DOUGHTY

For Don, my red-headed cousin in Canada, who also struggles with words

Contents

AUTHOR’S NOTE

In 1861, when our story begins, Ireland was ruled by Queen Victoria. Irish Members of Parliament went to London and represented all thirty-two counties. The internal divisions of Ireland were simply the ancient provinces, Ulster, Leinster, Munster and Connaught which every schoolchild knew. The northern province of Ulster was made up of nine counties, Armagh, Down, Antrim, Londonderry, Tyrone, Fermanagh, Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan.

Throughout the period of our story most people in all four provinces spoke Irish, unless they had come from Scotland or England in the first place. Many Irish speakers from Donegal went to Scotland each year to help with the harvest. There they learnt a second language which they called Scotch, but we would call English.

CHAPTER ONE

Donegal April 1861

The lough lay gleaming in the sunlight, its surface mirror calm. Not a breath of wind disturbed the stillness of the afternoon. No cart creaked on the stony track above the shore, no raven called from the mountainside. Close to the water’s edge, a swan swayed on its eggs and stood up. As it stretched it’s wings, minute ripples vibrated outwards from the tangled willow roots below the nest, running in ever-widening circles until they slapped noiselessly against a curving line of boulders.

For long minutes, stillness and silence reigned, as unusual in the length of this well-settled valley as the warm sunshine on such an early April day. Light glanced off new foliage, a column of midges rose and fell in the shadows beneath a gnarled hawthorn. Then came a sound to break the silence. A soothing, rhythmic sound, like the hum of bees around a hive. Flowing down the steep slope on the western side of the lake, the chant of children’s voices moved out over the water.

‘Ulster, Munster, Leinster, Connaught. Ulster, Munster, Leinster Connaught.’

On a low ridge between the rough track that ran along the lower slopes of the mountain and the boggy margins of Lough Gartan, a school house had recently been completed. It was so new, the grey-green mosses that mantled the encircling trees had yet to find a foothold on its dressed stone walls or slated roof. For yards around, the bare feet of children had tramped the ground so hard and so smooth that no growing thing could find a purchase on the dark, packed earth.

‘Antrim, Armagh, Cavan … Derry, Donegal, Down … Fermanagh, Monaghan and Tyrone.’

The new refrain had more urgency, then stopped abruptly. A single peremptory voice rang out.

‘You boy, Lawn. Stand up, turn your back on the board. Now tell me the counties of Ulster.’

‘Donegal …’

‘Yes …’

As the pause lengthened the class shifted uneasily in their seats. A big, burly lad, a good hand with a spade or a slane, Danny Lawn was no scholar. He could barely write his name and he had no memory at all for names and places.

‘Yes, indeed, Lawn. It is quite fitting you should put our native county at the top of your list,’ he said sarcastically. ‘Now we should like the other eight counties in any order you care to choose.’

With his back turned away from the blackboard where the counties were inscribed in the Master’s copperplate, only three of Danny’s classmates remained visible. With the simple logic of smallest at the front, largest at the back, the Master’s seating arrangements left him looking directly at two boys, his own older brother, Larry with his desk mate, Kevin Friel and one girl, Mary, the older of the McGinley girls from Ardtur, who sat by herself across the narrow corridor separating the boys from the girls.

Danny looked desperately from Kevin to Mary, knowing full well his brother would never lift a finger to help him. Larry might be the eldest in the family, but Danny was his mother’s favourite. Larry could never forgive him for that.

Mary’s eyes were fixed on the Master’s face. She didn’t dare move her lips in case he’d catch her. When the Master narrowed his eyes and fixed them firmly on Danny’s hunched shoulders, she glanced across at Kevin, hoping he’d help Danny out.

‘Aaa,’ began Danny slowly, as he tried to read Kevin’s lips. But Kevin’s lips stopped moving the moment the Master stepped from behind his desk and strode down the narrow aisle.

As soon as the Master left his desk a small child in the front row moved cautiously in her seat and followed his retreating figure with dark, troubled eyes. Rose McGinley knew the Master disliked Danny. It was not the first time he’d found an opportunity to disgrace him in front of the class.

Rose shivered. From where she sat she could see only the backs of Danny and the Master, but she could see her sister Mary, her face flat and expressionless, her eyes wide. She was frightened, she could see that quite clearly, though she’d never yet admitted it to her. She went on watching cautiously, perfectly aware that turning round could bring the Master’s wrath upon her if he was to glance behind him and catch her. None of the other children with whom she sat had dared take their eyes away from the blackboard.

‘Ah what, Lawn?’

‘I can’t mind, sur.’

‘Well, we’ll have to see if we can improve your memory, Lawn, won’t we? Sit down and stay sitting down,’ he barked, as he looked up at the clock. It was half past three exactly.

Seconds before he turned on his heel and strode back to his desk, she had swivelled round again and was sitting perfectly still, her hands folded, her eyes firmly fixed on the counties of Ulster as if they had never strayed for one moment.

‘On your feet, up.’

In a single practised motion the class rose, repeated a lengthy Irish prayer, said ‘Good afternoon, sir,’ collected their few possessions and filed out without a word, the back rows leading the way. Not a soul spoke even as they turned away towards their homes. They knew better. The Master’s ear was sharp. As they moved towards the scattered clusters of cottages that lay between the track and the mountainside, the swish of the cane and Danny’s muffled grunts were the only sounds to be heard.

By the time Rose emerged into the sunlight her sister was well ahead of her, walking quickly along the track, her head down, her practised eye picking out the worn boulders and humps of grass kinder to bare feet than the rock the winter frosts had splintered. She dawdled, looking around her and kept an eye on Mary’s purposeful stride.

Before and after school each day, Mary visited her father’s aunt, an old woman, strong in spirit, but unable to walk more than a few steps. Without her help there’d be no water from the well, no turf for the fire and no potatoes for the evening meal.

Moving slowly along the track behind her, Rose was surprised she hadn’t looked back. Usually she stopped as soon she was out of range of the Master and waited for Rose to catch up with her. Today she hadn’t paused. Rose glanced at her brothers as they ran past, walked a little more quickly as if she were following Mary, then slowed down again as soon as they were gone, her eyes darting from side to side of the rough track. Away ahead of her now, Mary strode on, wrapped in her own thoughts.

As she watched her sister’s retreating figure, her long-lashed dark eyes grew bright with excitement. As the last of her school fellows dispersed and Mary moved out of sight, she stopped dawdling, shot across the empty track, climbed nimbly over the ditch and crept along it till she reached the thread of path that ran between the grain and potato patches surrounding the small cluster of houses known as Ardtur.

Not yet eight years old, Rose was a fragile-looking child with pale skin and a mass of black, wavy hair. She carried no satchel, for only the oldest scholars were trusted with the National School’s battered reading books. Dressed in a worn shift, she moved with quick, light steps, her excitement growing as she made her way through rough, marshy ground and headed for the piles of boulders that marked the foot of the steeper slopes ahead.

They were much further off than she imagined, but she hurried on, thrilled by her good fortune and determined to get out of sight before anyone could call her back. Minutes later, she scrambled triumphantly through the tumbled remains of an old wall built from the stones dug out of the tiny fields that now lay behind her. She glanced behind her and hugged herself in glee. There was no sign of Mary or of anyone else.

She had never been so far from home by herself. Sometimes her mother took her for walks down by the lough or up the hillside beyond Aunt Mary’s small, dilapidated cabin, but she’d never been on the mountain before. Though she’d looked up at it every day for as long as she could remember, this was the first time she’d set foot on its worn and craggy slopes.

The bare patches of rock were easy on the feet, but the wiry stumps of burnt heather were best avoided. Here and there, tangles of briar had dropped dry, thorny twigs among the fresh shoots of bracken. She tramped on one, twisted her face in pain and stopped to pull out the thorns. After that, she moved more cautiously, her eyes no longer fixed upon the crest of the mountain’s long shoulder, until now the boundary of her world.

Despite the tiny breeze she met as she climbed higher, she was soon damp with perspiration, her face prickled with heat. She paused for a moment, wiped her forehead with one slender arm and stood listening. If there’d been rain at all in the last few days, the narrow gullies seaming the mountainside would be tumbling with water. She could make a cup with her hands and have a drink and splash water on her face to cool it.

The thought of it filled her with longing. She could almost feel the water sliding down her parched throat and the coolness on her hot cheeks, but there’d been no rain for over a week. Her only hope was a spring. She looked around her, but saw no sign of one. All those she knew came out low down, at the bottom of a hill or under a hedge bank.

She kept going, the cool breeze encouraging her as she climbed. Then she heard a call. It must be a bird, she thought. But when it came again, it sounded too like her own name to be a bird. She stopped and looked behind her. She was amazed at how far she’d come, the whole valley now spread before her. There was no one in sight on the slopes below or in the fields beyond.

She picked out the roof of her own house. Standing a little higher than those of their neighbours, it had pale gold streaks in the weathered thatch where her father mended it last autumn, then the roof of the school glinting in the sunlight. A little way from the gable end, a sapling with fat, grey-white buds raised its thin branches to the sky.

The day the school was opened, a man in a uniform had planted it. He was a nice man with a wife in a long dress and a big hat. He’d smiled at them and made a speech most of the scholars couldn’t understand, because they only had Irish. But she did because her mother had the Scotch. He’d said he was sorry it would be a bit too soon for them to benefit themselves, but he hoped his tree would give apples to their children and their children’s children.

The call came again. Startled this time, she turned abruptly from the green and sunlit prospect below to the bare rocky slopes of the mountainside. She shivered. The voice was above and ahead of her. Uneasy now, she searched for signs of movement, but nothing stirred in the stillness, neither bird nor animal.

Could it be a banshee? she asked herself. She wasn’t entirely sure what a banshee was, but she knew it was a bad omen if you saw or heard it. Most people said it’s cry was a sure sign of a coming death. Others said the banshee itself was death to travellers, it’s human voice leading them to their doom in bog or quicksand, over cliffs or precipices.

She paused, uncertain what to do. Aunt Mary said you couldn’t be too careful when you were dealing with the Other World, but you must always try not to give offence. She would do as Aunt Mary did. She crossed herself quickly, said a prayer to the Blessed Virgin, and continued her climb.

‘Where in the name of goodness are ye goin’ Rose. Are ye lost?’

She leapt backwards and nearly fell over.

‘No, I am not,’ she replied crossly, as she gathered herself up.

Owen Friel was leaning back in the shade of an overhanging rock, his worn, peat-stained shirt and trousers as dark as the rock itself.

‘An’ what are ye doin’ here yerself?’ she came back at him. ‘Ye weren’t at school. They’ll come after ye.’

‘Na.’

He shook his head dismissively and went on looking out over the valley below. ‘I’m near the age to go. Da says they’ll not trouble to come away up from Letterkenny. He’s workin’ on the new drains above Warrenstown. I brought him up a can o’ tea a while back.’

Owen lived further up the valley in the same cluster of cabins as Aunt Mary. She’d seldom seen him at school, but when he did appear he sat silent, looking out the window whenever the Master took his eyes off him. He moved to one side and made room for her to sit beside him on a slab of smooth rock. Her legs already aching, she dropped down gratefully.

‘Does yer ma know yer out?’ he asked without taking his eyes away from the prospect below.

‘No. She had to go over to Termon to get paid.’

He stared at her, puzzled.

‘What put the mountain in yer head, Rose? It’s no place for a wee girl. Ye might have hurt yerself,’ he said, kindly enough.

She was about to protest that she wasn’t ‘a wee girl’, but then she saw he wasn’t teasing her. And she was wee, it was true. In the row under the Master’s desk, she sat with the five and six year olds and she was nearly eight.

‘I wanted to see the other side of the mountain.’

‘What for?’

He sat quite still, a look of amazement on his face.

‘To see where the landlord’s goin’ to build his castle.’

‘Landlord’, he repeated carefully. ‘What’s that?’

She frowned and shook her head. She’d done it again. She kept forgetting that if she used her mother’s words no one would understand except her brothers and sisters and the tinkers who came to sharpen tools and mend pots.

‘Tiarna,’ she said quickly, ‘the man Adair they talk about every night when the neighbours come in.’

‘Has your father the Scotch then?’

‘He has, but not much. Only what harvesters have. But my mother has it. She always says she has very little Irish.’

‘Is she from Tullaghobegley then?’

‘Where’s that?’

‘Over beyond,’ he said vaguely, waving his arm towards the north. ‘My father once got work with a man there. He says there’s a whole lot o’ them speaks the Scotch all the time. He tried to pick it up, but he wasn’t there long enough.’

‘My mother’s from Scotland itself,’ she said proudly. ‘Her father had a farm and a house with six rooms and a byre and a stable. My Da went to harvest two years in a row and the third year she came back with him. She’s told me all about Scotland. She lived in a place called Galloway.’

Owen looked thoughtful as he took in this information. He had never heard of Galloway, nor had he ever known anyone who lived in a house with six rooms. Of course, she might be making it up. Children were always making up stories. But it wasn’t very likely she could make up words he couldn’t understand. And her such a wee scrap of a thing.

‘Will ye come with me?’ she asked, fixing him with her gaze.

He saw her dark eyes bright with excitement and smiled in spite of himself.

‘It’s a fair bit yet. Are ye sure ye can do it?’

She nodded vigorously. He got up, put out his hand, helped her to her feet and they set off.

‘You’ve a big sister, haven’t you?’ he asked, as they stopped for breath.

‘Yes, and two brothers. And a baby. It’s got red hair and it’s not walking yet.’

‘Five of you. There’s seven of us, or there was till Mike and Pat went to Amerikay.’

‘I had another brother and sister too, older than Mary, but they got the fever in the bad time. My Ma is always talking about them. She’s calling the baby for the boy, Samuel. The girl was Rose. I’m called for her. Ma says I’m like her when she was small, but then she grew tall …’

‘Save yer breath, Rose,’ he said, looking down at her as she began to gasp. ‘D’ye want to sit down?’

‘No. Not till we get to the top.’

They climbed on in silence, their eyes fixed to the ground. There were no briars now, nor tufts of heather, nor plant of any kind on this windswept ridge. Fragments of frost-shattered rock littered the ground slowing their progress.

‘There ye are,’ said Owen, at last.

A few feet behind him, she looked up, stumbled and winced as her foot caught the sharp edge of a stone. She steadied herself, wiped the sweat from her forehead and stood staring down at the great ice-gouged valley that lay below.

‘There’s not many trees,’ she said crossly.

The hillsides dropped more steeply and were even more bare and rugged than the slopes they had just climbed. A broad lough stretched from end to end of the deep trench between them. It gleamed in the westering sun like their own Lough Gartan, but no clumps of sally, or birch, or oak grew by the shore.

‘An’ there’s no people,’ she went on, looking up at Owen, who stood scanning the valley from end to end, his eyes narrowed in the bright light.

‘Where’s the people gone?’ she demanded. ‘An’ where’s the castle?’

‘Sure he hasn’t built it yet,’ he said absently.

‘I wanted to see the castle,’ she said irritably.

He glanced at her upturned face, saw the bright eyes fill with tears and turned away quickly. She was tired out. He should have had the wit to take her home when he found her.

‘Look down there, Rose, down near the water,’ he began trying to distract her. ‘Do you see a bit that’s paler than the rest?’

‘Aye, on the ground that sticks out into the water.’

‘That’s right,’ he said, relieved at her change of tone. ‘And this side of it, can ye see the big stacks like haystacks, only dark?’

‘Aye, a whole pile of them.’

‘That’s the whin and heather cleared off the bare bit. That’ll be where he’ll put the castle.’

‘An’ what’ll he do down there all on his lone?’

Owen laughed wryly.

‘He’ll do what all the big folk do. Eat and drink and ride round in his carriage and invite folk from away. He’ll not be lonely the same man,’ he added reassuringly, for the dark eyes that challenged him had filled up again. Tears were dripping unheeded down her flushed face.

‘We’ll come back in a week or two and see how it’s doin’,’ she said, sitting down abruptly. She rubbed her foot where it was bleeding.

‘It’ll take longer than that to get a castle going,’ he said, half to himself as she pinched her foot. ‘They have to dig deeper for a castle than for a house. An’ he’ll have to get a road made for the carts to bring in the stone.’

‘But there’s plenty of stone down there,’ she protested, wiping her eyes with the back of her hand.

‘Ach yes, but sure landlords don’t use mountain stone, they send for quarry stone. It’s a different colour and comes in blocks.’

‘What colour will it be?’

‘Sure how would I know, Rose, what’s in the mind of Adair, except the rumours that go round.’

‘Will he put us out?’

‘Who told you that?’

‘No one. I just heard it.’

He put his hands on her shoulders and turned her away from the prospect below. He knew now why he’d felt so restless and oppressed all day. He’d heard the same rumours and pushed them out of mind but they wouldn’t let him be.

‘Well, pay no attention at all,’ he said hurriedly. ‘It’s just some story. Is yer foot all right?’

‘Aye, it’s stopped bleedin’ now.’

He leant over and lifted her to her feet. She was so light the wind could blow her away. Her face was pale now she’d got her breath back and she was shivering in the breeze. If he was beat, he might be able to carry her. But not all of the way.

‘Come on now,’ he said, trying to encourage her. ‘Yer Ma will be lookin’ for ye. Ye don’t want her to think you’ve gone and got lost, do ye?’

CHAPTER TWO

Rose heard her mother call to Mary and felt the planks creak as the older girl got out of the box bed by the hearth, where once their father’s mother had watched the comings and goings of the house by day and listened to the talk of neighbours in the evenings. She rolled over sleepily into the warm hollow Mary had left in the straw mattress and dragged the thin coverlet round her more closely. But it was no good. Without her sister’s warmth, she soon began to shiver. She got up quickly and pulled on her shift and the wool smock her mother had made for her because she so often felt the cold.

There was no sign of her mother or father. All was quiet and dim. Newly-lit, the fire smoked on the hearth. Gusts of wind blew down the chimney every few minutes. They swirled the cold ash from yesterday’s fire across the well-swept floor and sent billows of thick smoke from today’s into every corner of the room. It was cold even with her clothes on. She wished she were back in bed with Mary.

She coughed, rubbed the smoke out of her eyes and peered through the open door. There’d been frost in the night and the ground was hard, the hen’s water frozen solid in the old tin bucket. Ice had formed on the shallow puddles that spread out between the houses whenever it rained. She saw her parents standing outside Andy Laverty’s house. Mary was with them and they were listening to the old man. She could see the baby wrapped in her mother’s shawl, but there was no sign of her brothers.

‘Ma,’ she called several times.

She didn’t hear, but her father did and waved her back indoors.

She moved out of the doorway, but went on watching, for she knew something was amiss. Andy was red in the face and waving his arms around in great agitation. Her father had an anxious frown on his face. He seemed to be asking questions because each time Andy spoke in reply he shook his head and stared down the track to the roadway. Andy was still talking when she saw her brothers, Patrick and Michael hurrying up the track. Danny Lawn was with them, striding out so fast they had to run to keep up with him.

‘What’s the news, Danny?’ her father asked abruptly.

‘They’re on the road the far side of Warrenstown,’ he blurted out. ‘Da said to tell you there’s no talkin’ to them. There’s Adair’s land agent and a whole lot of polis, and a gang of men with the ram and axes and the like forby. And they’re all from away. All strangers, though they’re talkin’ Irish the same as us. They just say they have their orders, there’s nothin’ they can do t’ help us.’

Suddenly, the baby started to bawl, so Rose only heard fragments of what her father said.

‘… she’ll have to go indoors if they’ll give her a place.’

As her father went on talking Mary put her hands over her face.

‘Danny, away back, good man ye are. Send me word if …’

The baby had only paused. Now he’d started again, as Danny set off at a run, struggling in her mother’s arms, his small fists beating the air, his red hair catching the first pale gleams of light from the rising sun.

Rose slipped quietly across the room and sat on her stool by the fire.

‘Good girl, you’re up and dressed,’ her mother began, her voice soft but firm. ‘Now you take Samuel while Mary and I make breakfast.’

Her mother lowered the child into her arms, his face red with the fury of his crying, tears still wet on his cheeks. She cradled him to her, delighted by his warmth. Babies were always warm. She shushed him and rocked him and sang to him, the way her mother and Mary did. To her surprise, he went to sleep immediately. Through the open door, she caught sight of her father going into the byre with Patrick and Michael, the ice cracking beneath their feet.

‘Is he puttin’ us out?’ she whispered to Mary, as the older girl leant past her and hung the pot to boil over the fire.

But Mary said nothing, her lips pressed tightly together, her face closed. She just glanced sideways at their mother, measuring oats from the sack in the corner of the room.

‘We’ll meet that if we come to it, Rose,’ she said evenly. ‘The day’s not over yet,’ she added.

From her stool by the hearth, the baby asleep in her arms, she waited, alert for any unfamiliar noise from outside.

As soon as they’d eaten their porridge, her mother despatched Michael and Patrick to take the donkey to graze by the wayside. She handed Mary a can of milk for her aunt in Warrenstown.

‘See she drinks it all, but don’t linger. Come straight back,’ she warned. ‘Don’t pay any attention to the strangers. There’s nothing you can do.’

She scraped the last of the porridge into a bowl and handed it to her husband. ‘Take that over to Andy, like a good man. He’s no fire lit yet to cook a bite.’

Rose watched her mother clear away the dishes from their meal. There was an air of busyness about her, but she did none of the jobs she usually did, like go to the spring for water, or bake bread for the evening. Even the floor was left unswept.

She stood still and silent in the doorway for a while, then turned back into the room and moved around, touching familiar things, picking them up, patting them and holding them.

A woman just turned forty, Hannah McGinley was still handsome. Taller than her husband Patrick and once as fair as he was dark, she moved with a kind of gracefulness that seemed out of place in such a humble home. Even when she bent to sweep the hearth with a goose’s wing or add turf to the fire, she had none of the awkwardness of women worn by childbearing and the burden of hard work.

Her hands were still soft, the nails clean and trimmed though deep seamed with fine lines. Once, when Rose had asked her why her hands weren’t like other women’s hands, she said it was because of the embroidery. If you did white work you had to keep your hands soft by rubbing them with meal or buttermilk.

‘Strange you should ask, Rose dear,’ she began, a wistful smile on her face. ‘An old woman who read fortunes once told me no matter how hard I worked, I’d always have the hands of a lady.’

Rose was just thinking about the hands of a lady when the baby woke up and cried again and this time there was no stopping him.

‘Good girl,’ Hannah said, taking him from her. ‘Bring me the shawl. Do you want to go and do a pee-pee?’

When Rose came back from behind the byre, her mother was feeding him, the shawl draped over her shoulder, covering both child and bare breast. She was singing, a song about a lad that was born to be King going over the sea to Skye.

They started with the house nearest the roadway. Old Mary McBride had barred the door. She sat stubbornly by her fireside when the urgent knocking came. It took a man with a hatchet only a minute or two to smash the door into kindling. They gave her five minutes to collect her possessions and get outside while they lined up the ram on the lintel above the door. When it gave way, the central part of the roof fell in, dust from the collapse pouring out from the empty doorway like smoke from a fire.

She stood there, stunned, shaking from cold and shock as ropes were secured to the gable ends. Men hauled on the ropes till they gave way and crashed down outside the cottage walls. The last support of the sagging roof removed, the remainder of the thatch pitched inwards to extinguish the fire on the hearth and obliterate all trace of a life that had survived even the Great Famine itself. Having ensured the cottage could no longer provide shelter, the men moved on. A tall, gaunt figure in dark clothes stepped forward and approached the shivering woman.

He bent down towards her and spoke slowly and carefully.

‘As you now have no home or any visible means of support I am to tell you that you are entitled to relief in Letterkenny Workhouse. A cart has been provided for transport. It is waiting over beyond.’

Only when old Mary McBride’s cabin was a heap of rubble did Patrick McGinley finally accept he was helpless.

‘Hannah, there’s nothing for it. What’ll we do?’

Rose thought there were tears in her father’s eyes, but she couldn’t be sure. When the smoke was as bad as it was today, they all had red eyes and now there was dust drifting through the open door from Mary McBride’s. She could almost taste it on the back of her throat, a stinging dryness.

‘Get me the box, Patrick, my love, while there’s time,’ she said softly, putting a hand to his cheek. ‘We’re not the only folk to suffer like this. It’s not new. Adair is only another Sutherland. He’ll only defeat us if we give in. We’ll not let him do that.’

Her father turned away without speaking, took a pronged fork from the tools by the open door and went into the tiny bedroom where he and Hannah slept. He returned moments later with a battered old metal box, its surface still dirty with tramped earth from the floor.

She opened it quickly and sorted through the contents. The largest item was a big fat book with a black cover. There was a packet of papers, a china tea cup and saucer decorated with flowers, a brooch and two little pouches with drawstrings.

Rose watched in fascination. She had never seen the box before.

‘Ma, what’s that?’ she gasped.

‘It’s your great-grandfather’s watch. You can hold it for a moment.’

But no sooner had Rose clutched the cold silver case of the fob watch that her eye caught the glint of coins.

‘Not a word,’ said her mother sharply, as she counted them and put them back in their pouch. ‘None of you will say a word about the watch or the sovereigns.’

She turned to her husband and handed the pouch to him.

‘When the Mackays were driven from Sutherland, they hadn’t a ha’penny. Put it on a string round your waist and cover it well.’

The sounds of falling thatch were coming closer by the minute. Quickly, Hannah McGinley dispersed the precious objects amongst her children, showing them how to hide them in their scanty clothing. Young Patrick was entrusted with the silver fob watch, Mary with the cup and saucer wrapped in an unfinished piece of white embroidery. Michael put the papers under his shirt and Hannah pinned the brooch on Rose’s shift below the woollen smock.

‘Gather up the potatoes from the barn, boys, and bring them here.’

She turned to her husband. ‘D’ye think they’ll leave us the cart, or will they say it belongs to Adair? And what about the cow?’

Her husband shook his head.

‘There was carts on the road earlier from Warrenstown going towards Glendowan. They must have let them go. But there isn’t much room in it. Will I put straw in the bottom for Rose and the baby? What else can we take forby?’

‘The sack of oats and the bit of flour left in the crock. A bit of turf and kindling for a fire.’

He turned to go and found the doorway blocked by a man about his own height.

‘I must ask you to remove yourself from Mr Adair’s property.’

For one moment, Patrick McGinley was overcome by blind fury. Sweat broke on his forehead and he felt every muscle in his body long to lash out at this man, this lackey, this miserable apology for an Irishman.

And then he heard his wife’s voice, cool and polite.

‘Patrick dear, ask the gentleman to step inside to deliver his message.’

He had never mastered the Scotch, but the way she said ‘Patrick dear,’ he could understand in any language she would ever speak.

‘No, astore, this man will never set foot over this threshold,’ he said in his own speech. ‘Come out with the children and we’ll be gone.’

He pushed past the man, brought out the donkey and cart from the barn and lifted Rose up into it. The boys added the bundles of oats and potatoes and turf.

‘Are you all right Rose?’ her mother asked.

‘Aye,’ she said, bravely.

She was cold and the bag of turf was poking into her, so closely packed was the small cart.

‘Can you hold the baby?’

The sun was setting and a thin rain was beginning to fall. The baby was warm in her arms as the cart moved out between the wrecked houses. The men had lit a fire and were feeding the flames with pieces of Andy Laverty’s door. Andy was nowhere to be seen.

The flickering light reflected on sweaty faces and strong, dirty forearms, on the uniforms and helmets of the police who stood watching. All around, people were coming and going, some trying to get back into the wreckage of their houses, some sitting crying on the doorsteps.

‘Don’t look back, Patrick,’ said Hannah, touching her husband’s arm as he pulled on the donkey’s bridle. ‘Nor any of you,’ she added, looking round at Mary and her brothers, who were following behind with the cow.

They made their way slowly down to the roadway in the fading light.

‘Which way?’

In the twenty years since Patrick McGinley had brought his Hannah back to the mountain, he had come to understand that when times were really bad and all he could do was despair, it was Hannah who could see a way. While he had her, he knew he’d never give in.

‘To the right. We’ll find shelter tonight in Casheltown.’

The rain slackened momentarily, then turned to sleet. The sudden squall blew in their faces, bouncing icy fragments on their clothes, drifting on the rough surface of the road. Rose closed her eyes as the hail stung her face. She drew her mother’s shawl closer over herself and the sleeping baby.

Above the creaking of the cart and the rush of wind, they heard behind them a shuddering crash. Though they all knew what it was not one of them looked back.

CHAPTER THREE

The journey from Ardtur to Casheltown was no great distance, but the heavily laden cart and the reluctant movement of the cow made progress slow. Bent forward against the scudding hail, they said not a word to each other but tramped along the rough, potholed track, eyes downcast, knowing that when they turned towards the next random gathering of cabins there would be some relief from the particles of ice that stung the face, caught in the hair and clung to their worn and shabby clothes.

As suddenly as it had come upon them, the squall passed. Through a gap in the cloud, the sun poured golden rays around them and they were dazzled by bright beams reflecting back from the skim of hailstones that lay as thick as a light fall of snow.

‘Thanks be to God,’ said Hannah, lifting her head and straightening her hunched shoulders. She wiped the moisture from her face and smiled as the bitter chill passed away, the golden light streaming down from a widening patch of blue sky adding a touch of warmth to the evening air. She turned to the younger of the two boys.

‘Michael dear, run away on up to Daniel McGee and tell him we’re coming. If the door is maybe shut and barred, knock very softly and call his name.’

She tapped her long fingers on the wooden frame of the cart. Rose wondered if she was tapping out the beginning of a song.

Michael looked up at her, his face still damp from the melted sleet and solemnly repeated the rhythm on the rim of the cart. Rose knew he’d got it right, even before her mother smiled.

‘Good boy, yourself,’ Hannah said, as Michael took to his heels, pleased to be given a task after all the long hours of waiting.

Daniel McGee’s door was open by the time they arrived. Born in the 1780s and blind from birth, he stood waiting for them, greeted each of them by name, though only Hannah stepped forward to press his hand, for he was uneasy when people came too close to him. He always said he could ‘see’ people better if they were further away.

‘You’ve none of you taken harm?’ he said abruptly, when he had studied each one of them. ‘Are we to have one more night?’ he went on, addressing Patrick McGinley, who stood by the donkey’s head wondering what to do next.

‘Aye Daniel, we are. Sure haven’t Adair’s fine, strong men worked hard and long the day. Won’t the factor want to see they’ve good food and rest against the work of the morrow?’

He spoke bitterly as he took the sleeping baby from the cart and put him in Hannah’s arms. Then he picked up Rose, swung her into the air, twirled her round his head till she laughed with glee and set her gently down again on her own two feet.

A look of desolation passed over the old man’s face at the sound. Wherever he ended his days, and those days might be few enough, Hannah thought, he’d never again hear the laughter of children in the valley where he’d been a child himself.

‘Come in, Hannah, be ye welcome as ye always are. I’ve little to offer, but what I have is yours.’

Daniel McGee’s house was about the same size as theirs had been, but there was no division to make a bedroom, so the single room seemed much larger than their own, its roof much higher, for it was raised in better times. Rose stared at the smoke-blackened sods that lay under the thatch. On the pale, silver-grey wood of the lowest laths St Bridget’s crosses had been nailed up each year on her special day. Some were woven from rushes. Some carved from the whitened tree stumps dug up with turf from the bog. A few were just pieces of sharpened stick bound together with a piece of rag. She began to count them softly to herself as her brothers brought the bundles from the cart.

‘Can I hold the child, Hannah?’

Rose was amazed when her mother lowered Samuel into his arms without a moment’s hesitation. He sat rocking him gently and crooning to him while Hannah and Mary made up the tiny fire with turf from the cart and put water to boil for the potatoes they’d brought with them. Samuel opened his eyes, sneezed and then lay still, his arms waving gently, his large dark eyes attempting to focus on the face of the unshaven figure who looked down at him focused but unseeing.

By the time they’d eaten, the sun had dropped far behind the ridge of the mountain. Inside the big room it was shadowy, the only light the pale oblong where the door still stood open. Every so often, even that source of light was dimmed as another man or woman slipped through to join the growing company.

‘Come away in and let ye be easy. There’s no one but old friends among us tonight,’ Daniel called out firmly. He greeted each of his visitors by name before they’d even spoken.

He’d insisted Hannah sit in the wooden armchair that faced his own across the flags of the hearth. Beside it, he’d placed a low stool for Rose. Here she sat, her back resting against her mother’s legs, watching the silent figures settle themselves around the room.

Behind Hannah, Mary shared a bench with her father and brothers, but many of the people who arrived had no place to sit. They dropped down on the floor or stood leaning their backs against the walls. For what seemed a long time to Rose, no one spoke in the crowded room and no one came. Then two men carrying a wooden bench slipped into the back of the room and seated themselves. As if that were the signal he’d been waiting for, Daniel cleared his throat and began to tell a story.

It was a familiar tale of heroes she’d heard many a night, listening behind the bed curtains when she was supposed to be asleep. What was new to her was Daniel’s way of telling it. There were long and elaborate descriptions of places and people, clothes and weapons, castles and great houses, she’d never heard before. Sometimes the hero would pause and break into verse, praising his friends and drinking companions, cursing his enemies, celebrating the beauty of a woman or the paces of a fine horse.

Often Daniel would pause and ask a question, as if to be sure he had their full attention. At critical points in his tale, he would ask his listeners to express their feelings. ‘Ah bad luck to him,’ they would chorus, if Daniel had spoken of treachery. ‘God give you joy,’ they’d cry, as ill-used lovers ran off together to the shelter of the mountainside.

Daniel spoke in Irish, for he’d never left the valley and had no Scotch at all, but there were many words and phrases Rose had never heard before. At first she didn’t understand them, but as they were repeated, over and over again, slowly the meaning came to her. She wondered what her mother was making of them. For over half her lifetime, Hannah had spoken everyday Irish to her husband and her neighbours, her own Scots-English to her children. If asked, though, she was sure to insist she had little Irish.

Rose noticed she’d not joined in the responses and cries of encouragement. She wanted to look up at her and see if she could work out why she was so silent, but she knew she must move only very slowly and gradually, for there was no greater discourtesy to the teller of a tale than a fidget. Even if you got a cramp in your leg or wanted to scratch your back, you must put up with it till there was a break in the story.

When finally, during a burst of applause, she was able to turn towards her mother, Rose was quite taken aback, frightened even by what she saw, for suddenly she looked so old, her face pale and drawn, the wisps of grey hair usually drawn back into the still-fair tresses of her thick hair, straggling down on each side of her immobile face. Her eyes seemed quite dead and lifeless, though they glittered with moisture, her fingers locked tightly on her lap the knuckles poking out, white and angular, from the hands Rose so often admired for their softness.

A little later, the story ended. Cheers and handclaps greeted the triumph of the hero. There were cries of ‘Good man, yerself. Well told, God bless you,’ directed towards Daniel. Rose looked up at her mother again, saw her unclasp her hands and applaud with the others. At the very same moment, two large tears dropped silently onto the dark fabric of her skirt.

Daniel drew breath, the spell of the story broken. The forgetfulness it brought ended with it. The dark figures moved uneasily and took up again the burden that had haunted them for weeks and the fears became a reality this very morning with the news of the first evictions.

To Rose’s surprise, the voices fell quiet again and a sense of waiting returned. She wondered if Daniel would tell another story or whether he would call on someone to sing or play, though she’d seen no sign of anyone bringing an instrument.

‘Dear friends,’ Daniel began, stretching out his stiff and twisted hands as if to embrace them all. ‘I know what’s in yer hearts and minds. I feel it all around me. And yet in the midst of this great anxiety and fear, I feel something stir, a whisper on the air, as light as the perfume of the hawthorn in May and yet as wholesome as bread baking on a griddle.’

He paused and looked from face to face, though the soft glow from the orange embers would have been little enough for a sighted man to see by.

‘There is something in this room that would sustain ye on a hard road better perhaps than a full stomach. I feel it near me, though I cannot put words on it.’

He paused and then threw out his arm slowly, his fingers still incurved towards his own body as he leant across the hearth.

‘Hannah, good neighbour, is there something that speaks in your heart?’

For a long moment Rose thought her mother wasn’t going to say anything. Then, at last, she spoke.

‘Daniel, old friend, I have no skill at all in your art of storytelling and I have little Irish. Or so I thought, till I heard you speak tonight. You have brought memory to life for me and, though my mind is troubled as we all are, I will tell you what I have remembered.’

Rose had never noticed before how soft her voice was when she spoke Irish, but of course, she’d only heard her say everyday things to her father and neighbours. Perfectly at ease in herself now, she smiled and went on.

‘I make but one condition,’ she said, looking round the company, ‘That you judge me lightly on matters of date for which I have no head and on words I may not have, though this little one here may well supply me,’ she added, dropping a hand lightly on Rose’s shoulder.

There were murmurs of assent and words of encouragement from every part of the room. Daniel himself nodded vigorously. ‘Good woman, good woman yourself. We’ll not fault you for what is no fault at all.’

Hannah drew breath and began, her tone light, her soft voice floating effortlessly over the silent company.

‘My great-grandfather was John Mackay of Scourie in Strathnaver and his wife Hannah, whose name I bear, was of the same proud clan, but she was from Tongue on the north coast, a wild and beautiful place I’ve heard tell, for I was born in the south, in Galloway.’

Rose was entranced. When her mother spoke of her great-grandfather, her voice was full of a quality she’d never heard before. ‘John Mackay of Scourie’, she’d said. But it sounded more like ‘Victoria, Queen of England.’

‘My grandfather would be as old as Daniel, had he lived,’ she went on. ‘A strong-built man, but not tall. He had red hair and was a doughty fighter. He followed his lord into many a battle in a war that lasted for seven long years. He fought in Germany and in Denmark and many places whose names I never knew. But although the life of the camp was meat and drink to him, he always came home joyfully to his glen and to his wife and sons. He was wounded many times, but his lord gave him both money and land for his faithful service and he was content. His family flourished. They had plenty to eat and could always pay their rent.’

The silence had deepened. Hannah’s tone was as light and as steady as ever, but something in the way she held herself upright in her chair seemed to warn her listeners that this pleasing picture could not last.

‘I know little of the doings of great folk, those who live in castles and raise armies and fight wars against other countries. What I do know is that what little we hear of such people, their lives and loves, their friendships and enmities, are often more story than truth. Rumours flourish round a castle gate even more than at our own lane-ends. But what seems to have happened is that the great Chief of the Mackay made bad decisions or was cheated, so that he lost much of his land. The man that benefitted from his loss was from England, but he employed a Scotsman called Patrick Sellar to do his work for him, and an evil work it was for the land of Sutherland and, most of all, for the Mackays of Strathnaver.’

She paused, as if the mention of Patrick Sellar had been hard for her. Then she smiled.

‘When I was a child I would have been punished for speaking that name,’ she explained easily. ‘But time moves on. He has been judged by God long since. He was a man, like Adair, that had no time for the little people. Perhaps he was cruel, as some said he was. Perhaps he didn’t know the hurt and harm his action would cause. But whatever the truth of it, his agents sent thousands of people from the lands of Strathnaver to dwell on the rocky shores of the north. Men and women were driven from their homes, settled far away with no land to grow their food and no knowledge of the sea to provide what sustenance there might be. Many died trying to fish in the wild, northern waters. For the old and the weak, the children and the sick there was no future. They died, just as many of our friends and our family died in the bad time.’

Rose thought of her sister, who would be older than Mary had she lived, and her big brother Sam, who had red hair like the baby. Were they all going to die too, now that Adair had put them out?’

She looked up at her mother and saw that she was looking round the room, her dark eyes meeting those of everyone there.

‘Yes, many died. That is the heartbreak that the great ones inflict upon such as ourselves. And it may come to that for some of us,’ she said sadly. ‘But not for all.’

She took a deep breath.

‘My father and his brother walked the length of Scotland on burn water and berries from the hedgerows and the scraps of bread kindness brought them. My father found work in Dumfries and then bought land. He worked hard. He had fifty acres before he sold his farm, for he had no son. My uncle earned his fare to Nova Scotia and settled among the Rosses from Skye. He traded with them and became rich. They’re both dead now, but while they lived they never forgot their family. It was not the hunger that took our Rose and Samuel from us,’ she added softly.

There was a pause and Rose remembered the day she’d asked why her brother and sister had died.

‘There was a fever that came when people got very hungry,’ her mother had said. ‘Even those who still had enough to eat could catch the fever. Many children caught it. Mary and Michael had it too, but they recovered. Rose and Samuel died in the same week.’

‘And did I catch it too?’

‘No, my love, you didn’t. You were not born till the worst was well over and I fed you myself for a long time. Your father was poorly for a while, but he threw it off. He has always been strong.’

‘And you Ma. What about you?’

‘Me? I prayed I’d be spared to care for the rest of you. And I was.’

The room was silent and growing cold as the last embers of the turf fire shivered and fell to ash. Daniel was looking at her mother now, his face pale below the dark stubble of his unshaved face.

‘And what words did your father and his brother leave with you Hannah, when they spoke of their ordeal?’

‘They said they had found strength when they least expected it, they had found comfort in the most desolate of places and they had found the richest of hospitality in the poorest of places.’

‘Did they now?’

Daniel repeated Hannah’s words softly to the silent room.

‘And did either of them give you any advice when you gave up your comfortable home to marry your chosen man and come to this hard place?’

‘Yes. My father spoke to me before Patrick and I were married. He knew he would most likely not see me again. He was heart sorry that I was marrying across water and to a man of a different religion to his own, but he respected Patrick and knew he was a good man. What he said to me was this:

“Hannah, you have joy now in this marriage of yours. Long may it last. But none of us passes through life without hardship and great sorrow. Shed tears for your grief, but do not hold bitterness against any person or any situation. Bitterness stuns the spirit and weakens the heart. Accept what you cannot change and ask God and your fellow men for comfort. In that way you will live well however short your span. Give in to the bitterness and you will never fully live though you go beyond three score years and ten”.’

The last orange sparks on the hearth glowed and faded as the wind blew down the chimney. The single candle that someone had lit and placed on the dresser flickered and steadied.

‘There, friends and neighbours. There are words to put in your hearts when the men come tomorrow. Remember what Hannah has shared with us, both the ordeal of her father and uncle and the experience they gained from it. May God in his mercy watch over us.’

CHAPTER FOUR

May 1875

As soon as she’d climbed well above the coach road, Rose paused between the low, wind-bent fuchsia bushes and undid the top buttons of her blouse. The fine cambric, stitched into narrow pleats over her breasts and gathered with ribbon at the neck, dropped back and exposed her pale skin flushed with heat and gleaming with perspiration from the effort of the familiar, short, steep climb.

She turned and gazed back down the rocky hillside now patched with rich summer grass and dotted with early flowers. With a few deft movements she pulled out the long hairpins from the neat coil at the back of her head.

She felt the light touch of the sea breeze as it flowed in over the broad lake below. ‘Oh, that’s better, a hundred times better,’ she said aloud.

She shook back her dark mass of hair and tucked away the few tendrils that were blowing across her eyes. All around her, the red tassels on the fuchsia bushes moved gently to and fro, tall stems of mayflower swayed easily above the smaller, brighter plants growing in their shadow. The breeze was a delight, cool, but with no edge of chill. She stood drawing in a deep breath of the clean, salt air like someone drinking spring water after a long, dusty journey.

After a few minutes, she began to struggle with the tiny seed pearls at her wrists. However much she loved the pretty buttons, they always made her cross when she was hot, or tired, or just wanted to pull off her clothes and fall into bed. She laughed at herself as she pressed patiently with damp fingers till they slid through the close-fitting buttonholes her mother had stitched with such patience.

None of the other servants at Currane Lodge wore such an elegant blouse. Even were they so fortunate as to possess one, they would most certainly not have been allowed to wear it. But then, none of them was lady’s maid to the eldest daughter of the house. Given Lady Anne Molyneux’s temperament, none of the other house servants envied her the privileges that came her way. She rolled up her sleeves and felt the soothing touch of the cool air on her warm body, threw back her head and stretched out her arms above her head as if to embrace the whole sunlit hillside and the blue dome of the sky above.

Suddenly, the air around her was filled with sound. Surprised and delighted by the shower of notes pouring down upon her she scanned the sky above. Dazzled by the light, all she could make out were two minute brown specks that shimmered and dissolved and then reappeared yet further away. She shaded her eyes. Immediately, the two specks became one as the lark rose higher in the clear air, its song bathing the quiet hillside where the only other sound was the murmuring of insects drunk with the first honey of the season.