Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

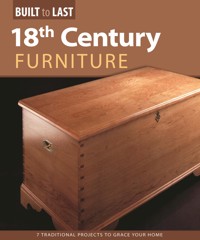

- Herausgeber: Fox Chapel Publishing

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Step-by-step projects for building beautiful Shaker furniture for every room of the house. About the Series: Discover the timeless projects in the Built to Last Series. These are the projects that stand the test of time in function and form, in the techniques they employ, and represent the pieces every woodworker should build in a lifetime.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 160

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

© 2010 by Skills Institute Press LLC

“Built to Last” series trademark of Skills Institute Press

Published and distributed in North America by Fox Chapel Publishing Company, Inc.

Shaker Furniture is an original work, first published in 2010.

Portions of text and art previously published by and reproduced under license with Direct Holdings Americas Inc.

ISBN 978-1-56523-467-3

eISBN 978-1-63741-554-2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shaker furniture.

p. cm. -- (Built to last)

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-56523-467-3

1. Furniture making. 2. Shaker furniture. I. Fox Chapel Publishing.

TT197.S565 2010

684.1--dc22

2010004190

To learn more about the other great books from Fox Chapel Publishing, or to find a retailer near you, call toll-free 800-457-9112 or visit us at www.FoxChapelPublishing.com.

Note to Authors: We are always looking for talented authors to write new books in our area of woodworking, design, and related crafts. Please send a brief letter describing your idea to Acquisition Editor, 1970 Broad Street, East Petersburg, PA 17520.

Because working with wood and other materials inherently includes the risk of injury and damage, this book cannot guarantee that creating the projects in this book is safe for everyone. For this reason, this book is sold without warranties or guarantees of any kind, expressed or implied, and the publisher and the author disclaim any liability for any injuries, losses, or damages caused in any way by the content of this book or the reader’s use of the tools needed to complete the projects presented here. The publisher and the author urge all woodworkers to thoroughly review each project and to understand the use of all tools before beginning any project.

Contents

Introduction

CHAPTER 1:

Shaker Design

CHAPTER 2:

Chairs

CHAPTER 3:

Tables

CHAPTER 4:

Pie Safe

CHAPTER 5:

Shaker Classics

What You

Can Learn

Shaker Design here

Simplicity is the quintessential hallmark of the Shaker design.

Chairs, here

As one of their early catalogs proclaimed, Shaker chairs offered “durability, simplicity, and lightness ”.

Tables, here

Shakers created tables that found a multitude of applications, from the dining room to the dairy to the infirmary.

Pie Safe, here

These storage cabinets were once common in American kitchens.

Shaker Classics, here

The wall clock, the step stool, the oval box, and the pegboard are classic examples of the principals that guided the Shakers in their daily lives.

Introduction

Redefining Shaker Style

I was fortunate enough to live at the Canterbury Shaker Village in New Hampshire for 14 years, from 1972 to 1986. My parents ran the Village Museum and we were given housing in the Children’s House, built in 1810. I had the privilege of knowing seven Shaker Sisters and listened to their beliefs and memories of the old days. While living there, I found myself exploring and studying the architectural elements of the buildings, as well as the furniture in the collections.

While living in these unique surroundings, I had the exceptional opportunity of apprenticing with an Old World cabinetmaker from Madrid, Alejandro de la Cruz. His teachings emphasized tradition, classicism, and integrity in work, design, and living. This apprenticeship provided me with a direction and focus for studying Shaker and other classic designs. At the same time, it allowed me to constructively criticize some old pieces and to rebuild or redesign them by using better construction methods, while still retaining their original charm and attractiveness.

Like the architectural elements of antiquity, the beauty and truth of Shaker design are most evident in basic forms. The overall lines, proportions, and stance can be seen in a simple piece of furniture like the candle stand shown in the photo at right. Details, if they are done well, add a further dimension and will not obscure or clutter the general form.

I do not believe that the Shakers set out to develop their own designs; rather, their beliefs reshaped forms with which they were already familiar. Shaker design can be seen as a stripped-down Federal style, with emphasis on Hepplewhite and Sheraton elements. Federal style was concurrent with the beginning and the development of the Shaker religious movement. The key cabinetmakers of each Shaker village were also free to develop the unique flavor of each community’s work while taking direction from the lead community of Mount Lebanon, New York.

While a good deal of Shaker design charm lies in its naiveté, even more depends on the cabinetmaker’s complete mastery of the form. Creating furniture designs requires a thorough understanding of the design process, and being able to “get into the heads” of the old masters to understand why certain design decisions were made. It also requires a good understanding of furniture construction using past and present techniques. It is important not just to acknowledge a piece as a masterpiece and copy it, but to find out why it is a masterpiece, by asking many questions about it. The answers will provide your building blocks for creating your own designs in any style.

- David Lamb

David Lamb was resident cabinetmaker at Canterbury Shaker Village, New Hampshire, between 1979 and 1986. He now builds Shaker-inspired furniture at his shop in Canterbury.

Elegant Shaker Box

I first saw Shaker boxes in a pattern book on Shaker woodenware by Ejner Handberg in 1977 when I was teaching furniture making at Lansing Community College. Even as line drawings, these simple, elegant oval containers, crafted from cherry in graduated sizes, were intriguing. All boxes hold universal appeal, but to have them nest inside each other appeals to the child in all of us.

Up to this point, I had been a carpenter in residential construction for 10 years, and had spent another decade teaching social anthropology. Little did I know when I began to follow my curiosity in Shaker oval boxes that they would become the perfect avenue for expressing those three skills—working in wood, interpreting other communities’ life and work, and teaching. But that is exactly what has happened to me over the last 15 years.

By specializing in Shaker oval boxes, I was fortunate to take advantage of three trends: a growing awareness of Shaker design, the popularity of woodworking as a hobby, and an interest in instruction in leisure activities. This combination opened the doors for freelance box-making seminars. By 1986 I was teaching 30 workshops a year in many parts of the country, as well as in Canada and England. The participants make a nest of five boxes. It is fulfilling to be able to master the technique of making a box, and even more so to perfect it in making five. In the 12 years since the first box class, I have taught more than 4,000 people this traditional craft.

My memory of first attempting to build them is of bands breaking, bringing the project to an abrupt end. It takes more than line drawings to master technique. Visiting Shaker sites in New England, I recall a rare opportunity to watch box maker Jerry Grant at Hancock Shaker Village. He gave me a sample of the tiny copper tacks that are the hallmark of the box lap. These are as scarce as hen’s teeth, as the expression goes. At the time, Cross Nail Company was the one remaining tack manufacturer, and made them only on special order. It took a minimum of 50 pounds to order, and with over 750 tacks to the ounce, that was an incredible supply. With 12 tacks needed to make a box, it also represented a lifetime of box making.

Today, Shaker boxes have become my life and supplying the box trade with quality materials now occupies more of my time than either making boxes or teaching. More than just being good business, making Shaker boxes has left me with the conviction that passing on our skills is a responsibility each of us must accept.

- John Wilson

John Wilson taught social anthropology at Purdue before turning his attention to teaching Shaker box making full time in 1983. His seminars have been held at the Smithsonian, in Shaker villages throughout America, and in England. He owns and operates The Home Shop on East Broadway Highway in Charlotte, Michigan.

A Shaker Life

When I was little and shared a room with my sister, I yearned to have a room of my own. I was 19 when that dream came true, and oh, what a room it was, in an early 19th-Century Shaker building in Canterbury, New Hampshire.

My room was a classic Shaker interior, with built-in cupboards and drawers, a peg rail around the walls, and rare sliding shutters. Everything overhead and under-foot was the work of Shaker Brothers who had used local pine, maple, and birch and a combination of hand tools and water-powered machinery in an efficient and sophisticated system of man-made ponds and mills behind the village. After a century and a half of continual use, the pegs were firm in their sockets. The drawers slid smoothly with a slight tug on the single center pull. The whole effect was one of spaciousness, airiness, and lightness. This room was worth the wait.

By the time I arrived at Canterbury in 1972 as a summer guide in the museum, the Shaker Society had long since flourished and faded. The Canterbury Shakers were established in 1792 as the seventh of what became 19 principal settlements in America. When I came, the half-dozen Shakers who lived there—all in their 70s, 80s, and 90s—were one of the last two Shaker families in existence. (The other was Sabbathday Lake in Maine.) The Sisters were delightful—energetic, humorous, and unstintingly kind. There were no Brothers at Canterbury. The last one had died in the 1930s and the women joked that they had “worked those poor men to death.”

While woodworking had passed into history with the last of the Brothers, the Sisters held the work of the “old Shakers” in high regard. A lifetime of using Shaker desks, tables, work counters, chairs, and cupboards had given them a hands-on appreciation of the qualities that have earned Shaker design respect worldwide: strength, lightness, and a simple rightness of proportion. Ergonomic? You bet. We held our breath whenever the fragile but unstoppable Eldress went up and down the stairs with her bad knee and cane, but the breadth of the steps, the gentle rise, and the sturdy, elegant handrail kept her upright and safe.

“Hands to work and hearts to God,” a homily of Shaker founder Mother Ann Lee, was a road map for good life. My Shaker friends are gone now, but their work endures as testimony to the beauty and wisdom of that simple message.

- June Sprigg

June Sprigg has been studying the Shakers for most of her life, and she was Curator of Collections at Hancock Shaker Village between 1979 and 1994. Her latest book with photographer Paul Rocheleau, Shaker Built, is published by Monacelli Press. She lives in Pittsfield, Massachusetts.

SHAKER DESIGN

The Shakers are recognized today as one of America’s most interesting communal religious societies. Thanks to the vigorous crop of books, articles, and exhibitions that have sprouted up since the Shakers’ bicentennial celebration in 1974, most people think of them first and foremost as producers of simple and well-made furniture. But in their heyday from 1825 to 1845, they were better known for their original blend of celibacy and communalism, a deep commitment to Christian principles as practiced by Christ’s disciples, and a worship service unique in civilized America for its group dancing, a sort of sacred line or circle dance that gave all members equal opportunity to express the Holy Spirit. This ecstatic dance scandalized many conventional observers, induding Ralph Waldo Emerson and Charles Dickens.

By the mid-19th Century, when the lithograph shown above was made, the frenetic dancing that once marked Shaker worship—and gave them their name—had been replaced with more reserved line dances. As in all Shaker activities, the sexes were strictly divided. The woman in stylish Victorian dress in the foreground was probably invited by the Shakers to observe their worship.

With its backward-leaning rear legs and curved slats, the Enfield side chair shown at left was built for simplicity and comfort. The rush seats on early Shaker chairs like this one gradually gave way to canvas tape seating.

The dining hall at the Pleasant Hill community in Harrodsburg, Kentucky.

Mother Ann’s New Order

The Shakers trace their history in America to 1774, when founder “Mother Ann” Lee emigrated to New York from Manchester, England, with eight followers. The 39-year-old daughter of a Midlands blacksmith, Ann Lee was prompted to come to the North American colonies, according to her faithful believers, by a vision of the second coming of Christ. She was sickened by the corruption of the Old World, and the changes wrought by the Industrial Revolution that were altering the conditions of human life beyond all previous experience. She sought to establish a new order of life in the New World.

As preached by Ann Lee and her followers, Shaker life was one of hardship and self-denial. Being a Shaker meant living a celibate life with no possibility of bearing children, and working selflessly and equally alongside one’s Brothers and Sisters. It also meant living in isolation from the outside world, renouncing all private property, and taking solace in the purity of community and prayer.

Although Ann died a scant 10 years after arriving in America and her movement remained relatively small during her lifetime, converts began to join in droves in the years following her death. By 1787, the first large-scale communal Shaker Family had gathered near Albany at New Lebanon, New York. The New Lebanon community was to become the spiritual capital of the Shaker world through the next century. By 1800, missionaries had helped establish a dozen Shaker communities throughout New England, including ones in Enfield, Connecticut; Harvard, Massachusetts; and Canterbury, New Hampshire. By 1825, 19 principal villages were flourishing from Maine to points west in Kentucky and Ohio. In 1840, an estimated 4,000 Shakers were putting their hands to work and hearts to God in America’s largest, best known, and only alternative to mainstream life that existed on a truly national scale.

In spite of efforts to attract new converts, the Shakers’ numbers began to decline before the end of the Civil War. In 1875, Tyringham, Massachusetts, was the first Shaker community to close officially. In a century that witnessed so many revolutionary changes in American life it proved difficult for the Shakers—who changed so little—to maintain the momentum of their first 70 years. By 1900, the Shakers had dwindled to 2,000 members as Shaker villages closed their doors one by one. Today, just one community with fewer than a dozen members survives.

The spiritual center of Shaker life, the meeting house, is as modest and unpretentious as any Shaker building.

Harmony of Proportion

The Shakers were not an esthetic movement or a self-conscious school of design. In fact, their furniture, like their architecture and clothing, was derided for its excessive utilitarianism. Today, attracted by the simplicity of their designs, the world has begun to recognize their achievement, such as the clocks made by Brother Isaac Newton Youngs of New Lebanon, and the sewing desks and rocking chairs of Brother Freegift Wells of Watervliet, New York.

Simplicity is the quintessential hallmark of Shaker design. Compared with the opulent complexity of a Queen Anne highboy, for example, a Shaker chair is a paragon of austerity: four legs, three slats, a handful of stretchers, and a few yards of canvas tape for the seat. In an increasingly chaotic world, it is not difficult to see why the simple lines of Shaker furniture continue to hold appeal.

Shaker artisans also distinguished themselves by the quality of their work. They were encouraged to take the time needed to do the job properly. The communal family structure gave individuals freedom from thoughts of purchasing, marketing, sales, and all related business concerns—an experienced business staff took care of all that. Shaker woodworkers were taught in an apprenticeship system and generally worked in state-of-the art workshops with the best tools and machines available. The Shakers’ were also capable of inventing the best; the table saw, for example, was the brainchild of a Shaker sister. It comes as no surprise that many woodworkers today speak enviously at times of their Shaker counterparts.

Brother Charles Greaves outside the carpenty shop, Hancock Shaker Village, Pittsfield, Massachusetts, in the early 1900s.

A Lack of Ornamentation

The Shakers eschewed the sort of artistic freedom that allowed builders to design and make whatever they wanted. They seldom autographed their pieces because they took no pride in being recognized as individual artisans. The Shakers traditionally regarded embellishments as a waste of time and resources. Indeed, the few ornamental touches to be found on Shaker furniture—such as exposed dovetailing and the ubiquitous, neatly turned drawer pulls and rail pegs—invariably had a utilitarian purpose.

By spending obvious care and time on humble, useful things, the Shakers clearly announced their belief in a future worth living and in the ability of future generations to keep their craft alive.

On the following pages is an illustrated gallery of some of the most enduring pieces of furniture that serve as the Shakers’ legacy to modern woodworking.

Usually made with bent maple sides and with quartersawn pine tops and bottoms, oval boxes were used to store all typesof dry goods. They were constructed in graduated sizes so that each one could be stored inside the next larger size.

A tall clock serves as a boundary between the men’s and women’s sleeping areas in the Centre Family Dwelling at Pleasant Hill, Kentucky. Clocks also divided the Shakers’ daily lives into prescribed segments. There were specific times for rising, eating, working, and sleeping.

A Gallery of Shaker Furniture

Tables and Chairs

Dining room bench

Built to accommodate several diners around a table.

Trestle table (here)

The most common style of shaker dining room table. Built with glueless joinery and knockdown hardware, this table can be disassembled when it is not needed; the legs, feet, and trestle running along the top’s underside are positioned to maximize legroom.

Candle stand (here)

The tripod design gives this lightweight table good stability.

Drop-leaf table (here)

Attached to the top with rule joints, the leaves of this table can be extended when needed or dropped down to save space.

Revolving chair

Also called swivel stools or revolvers, these chairs were used in Shaker offices, shops, and schoolrooms.

Enfield side chair (here)

Made with a backward tilt to provide comfort without bending the chair’s rear legs. Early versions like the one shown featured rush seats; the shakers later relied on canvas tape, as in the rocking chair shown at right.

Rocking chair (here)

Has steam-bent rear legs and solid-wood rockers;the tape seating is available in a variety of colors and patterns. Also made in a ladder-back version.

Meetinghouse bench

Accommodated the faithful during Shaker religious services; with its solid pine seat, this simple and lightweight chair could be moved out of the way easily when necessary.

With their short backs, the splint-seat dining chairs shown above can slide under a table without any sacrifice of comfort.

Casework

Sewing desk