8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

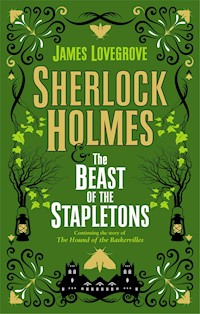

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

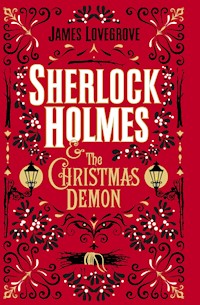

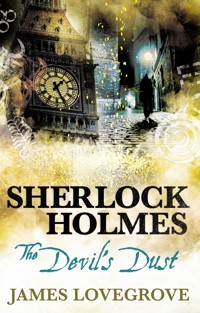

The new Sherlock Holmes novel from the New York Times bestselling author of The Age of Odin.It is 1884, and when a fellow landlady finds her lodger poisoned, Mrs Hudson turns to Sherlock Holmes.The police suspect the landlady of murder, but Mrs Hudson insists that her friend is innocent. Upon investigating, the companions discover that the lodger, a civil servant recently returned from India, was living in almost complete seclusion, and that his last act was to scrawl a mysterious message on a scrap of paper. The riddles pile up as aged big game hunter Allan Quatermain is spotted at the scene of the crime when Holmes and Watson investigate. The famous man of mind and the legendary man of action will make an unlikely team in a case of corruption, revenge, and what can only be described as magic…

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Also Available from Titan Books

Title Page

Copyright

Foreword

Chapter One: A Fraudulent Client and a Familiar One

Chapter Two: Inigo Niemand’s Last Supper

Chapter Three: The Shadower

Chapter Four: A Distaff Bluebeard?

Chapter Five: Macumazahn

Chapter Six: Hunting Hunter Quatermain

Chapter Seven: Daring Dan

Chapter Eight: The Peregrinations of Black Jack Corcoran

Chapter Nine: Encounters in the East End

Chapter Ten: Into the Hive

Chapter Eleven: The King of Shoreditch

Chapter Twelve: The Man in the Chair

Chapter Thirteen: The Choice of Target

Chapter Fourteen: V.R

Chapter Fifteen: Gone to Ground

Chapter Sixteen: The Siren Call of Excitement and Derring-Do

Chapter Seventeen: Silasville

Chapter Eighteen: The Skeleton Key that Unlocks Many a Door

Chapter Nineteen: Bat Amongst the Pigeons

Chapter Twenty: Another Kind of Jungle, Another Kind of Wildlife

Chapter Twenty-One: The Devil’s Dust

Chapter Twenty-Two: Under Fire

Chapter Twenty-Three: Romulus Minus Remus

Chapter Twenty-Four: The Angler’s Tale

Chapter Twenty-Five: A Vision of Highwaymen

Chapter Twenty-Six: Journey to Epping Forest

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Eyes

Chapter Twenty-Eight: Shepherded by Wolves

Chapter Twenty-Nine: The Thing-That-Should-Never-Have-Been-Born

Chapter Thirty: Impasse No. 1

Chapter Thirty-One: Impasse No. 2

Chapter Thirty-Two: The Magic of Science and the Science of Magic

Afterword

Acknowledgements

About the Author

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

Sherlock Holmes: The Patchwork DevilCavan Scott

Sherlock Holmes: The Labyrinth of DeathJames Lovegrove

Sherlock Holmes: The Thinking EngineJames Lovegrove

Sherlock Holmes: Gods of WarJames Lovegrove

Sherlock Holmes: The Stuff of NightmaresJames Lovegrove

Sherlock Holmes: The Spirit BoxGeorge Mann

Sherlock Holmes: The Will of the DeadGeorge Mann

Sherlock Holmes: The Breath of GodGuy Adams

Sherlock Holmes: The Army of Dr MoreauGuy Adams

Sherlock Holmes: A Betrayal in BloodMark A. Latham

Sherlock Holmes: The Legacy of DeedsNick Kyme

Sherlock Holmes: The Red TowerMark A. Latham

COMING SOON FROM TITAN BOOKS

Sherlock Holmes: The Vanishing ManPhilip Purser-Hallard

JAMES LOVEGROVE

TITAN BOOKS

Sherlock Holmes: The Devil’s DustPrint edition ISBN: 9781785653612Electronic edition ISBN: 9781785653629

Published by Titan BooksA division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd144 Southwark St, London SE1 0UP

First edition: July 20182 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

This is a work of fiction. Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2018 James Lovegrove. All Rights Reserved.Visit our website: www.titanbooks.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

What did you think of this book?We love to hear from our readers. Please email us at: [email protected], or write to us at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online, please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website.

www.titanbooks.com

FOREWORD

The early portion of my friend Mr Sherlock Holmes’s career is to a large extent terra incognita as far as these humble memoirs of mine are concerned. In my defence, I am hardly spoiled for choice when it comes to selecting material suitable to present to my readers. The commissions Holmes received were sporadic during the years when he was establishing himself in his unique vocation, for he had yet to garner the reputation – a reputation I have gone some small way towards fostering – that would lead to more extraordinary and compelling cases being brought to his attention.

One episode from this period of his life nevertheless clamours to be recounted. It tells how Holmes crossed paths – and swords – with a certain adventurer whose prowess as a big game hunter was second to none, and whose escapades on the African continent were becoming the stuff of legend, even as the man himself was entering the twilight of old age.

Here, then, is a narrative detailing how Sherlock Holmes, a man of mind, met Allan Quatermain, a man of action, and the dramas that ensued.

John H. Watson, MD, 1904

CHAPTER ONE

A FRAUDULENT CLIENT AND A FAMILIAR ONE

“I assure you, sir,” said Sherlock Holmes, “I shall not be taking your case.”

The man seated opposite him was agog. I myself was not a little surprised.

“But… But…” Mr Farley Danvers spluttered. “For heaven’s sake, why?”

“For these reasons.” Holmes ticked them off on his fingers one by one. “First, you are not, as you claim, a concert pianist. Second, you do not have a twin brother, identical or otherwise. Third, you are in the habit of not paying bills promptly. You are, to put it bluntly, a cheat, and I want no truck with you.”

Danvers brandished a chequebook. “You would refuse money?”

“You do not deny my accusations?”

“I deny them most vehemently. I have set out the facts of my predicament with all honesty. I am willing to employ you, at the going rate, to conduct an investigation into the theft of my property. Surely you cannot turn me down.”

“I can and I shall,” said Holmes. “Your game, as I see it, Mr Danvers, is to make me complicit in an insurance swindle. You wish me to prove that certain valuables were stolen from you and pawned, whereas in truth they have not been stolen at all. You would have me write a letter to your insurers, confirming the loss, whereupon they would recompense you. You would then use some of the money to get said precious items out of hock, and keep the remainder as profit. In short, your intention is to use my good name in order to further your immoral ends. Is that not so?”

“Not a bit of it!” the other declared.

“To make matters worse, I foresee that you will dun me at the first opportunity. I would wager that any cheque you write will not be honoured by your bank.”

“My credit is as good as any man’s.”

“I doubt it,” said Holmes. “And now, I would be grateful if you would see your way to leaving, this instant. Or will I have to remove you forcibly?”

With many further expostulations of indignation, Farley Danvers stormed out of our rooms.

I shot my friend a searching glance. “Really, Holmes, are you sure he was a crook? He seemed perfectly upright to me.”

“Quite sure, Watson. Everything he said was sheer, unadulterated twaddle. Concert pianist? Bah! Did you observe his fingers? Those were not the fingers of a man proficient in that art. The nails were too long, for one thing. A professional pianist trims his short. The tips were not flattened, either, as the fingertips are of somebody who regularly practises at the keyboard for hours. Nor did his hands have the musculature which develops from such activity, particularly in the palms and the wrists.”

“I see. So why pretend to be one at all?”

“For effect. Concert pianist, after all, is altogether a more impressive occupation than, say, wine merchant, Danvers’s actual livelihood. And in anticipation of your next question, his tie sported the coat of arms of the Worshipful Company of Vintners.”

“But how did you know he was not a twin?”

“Danvers referred to his brother by name three times. Twice it was Edward; the third time, Edwin. Who would misremember their own brother’s name?”

“It may have been a slip of the tongue.”

“Hardly likely, Watson! Have you ever got your late brother’s name wrong? Besides, he was wearing a gold signet ring bearing a family crest. The ring had the patina of age, denoting that it must be an heirloom passed down through the generations. Such an item of jewellery traditionally goes to the first-born son, yet Danvers averred that his brother was his senior by some five minutes. Why, then, would Danvers have the ring rather than Edward – or, as it may be, Edwin – unless Edward or Edwin was a fabrication?”

“And his failure to pay bills promptly?”

“As to that, did you not notice how badly the hair at the back of his head was cut, while the rest was comparatively neat?” said Holmes. “It is clear his barber chose to get away with the minimum amount of effort, doing a shoddy job with the parts of hair that Danvers would not himself see. That suggests disgruntlement.”

“Or else a slapdash barber.”

“I grant you the possibility. However, Danvers’s shoes had recently been re-soled, and again, as with the barber, the cobbler was less attentive to his task than he ought to have been. The cutting, gluing and nailing were all of poor quality. One negligent tradesman might be regarded as misfortune. Two begins to look like a pattern. A customer who consistently pays late is a customer who receives poor service.”

“So when Danvers said that he suspected his brother of being behind the disappearance of various treasures from his household…?”

“It was the purest hogwash,” said Holmes. “I believe he would have had me hunting high and low for the non-existent sibling.”

“But why invent a brother at all?”

“What a tragic yarn Danvers spun. All that stuff about this identical twin who had fallen on hard times and whom he had invited under his roof and taken under his wing – this layabout who had then rewarded his kindness by pilfering from him. It is the ‘identical’ part of the story that counts, for if I had managed to trace the pawnbroker now in possession of the articles and asked for a description of the man who sold them to him…”

I finished the sentence. “The description would have matched that of Danvers himself.”

“In short, Farley Danvers was, in a rather clumsy way, covering himself against such a contingency,” said Holmes. “He would have signed the pawnbroker’s statutory declaration form as ‘Edward Danvers’ and would swear blind, when pressed, that it was not he who brought the items to the premises but his twin.”

“Well,” I said, “all in all it’s a good thing you saw through him. You might otherwise have wasted a lot of time. Ought we not report him to the authorities?”

“Oh, even the dullest-witted insurance clerk will see through his tissue of lies. No, Watson, we need not detain ourselves over Mr Farley Danvers a moment longer. The impertinent fool will get what he deserves, with or without our involvement.”

“What a shame, though, that he was not a genuine paying client. You could do with the money, Holmes, if you don’t mind my saying so. Work has been thin on the ground for you lately.”

In truth, at that time – the autumn of 1884 – Sherlock Holmes was anything but overburdened with employment. His career as a consulting detective was, if not in its infancy, then certainly experiencing the pangs of adolescence. It had its peaks and its troughs, but signally more of the latter than the former. Clients were not falling over one another to get to his door. Indeed, the previous year had yielded but one case that I have since considered fit to chronicle – the business with the swamp adder at Stoke Moran – while the few others proved tawdry, uninteresting affairs. The same was true of 1884, save for the events I am setting down in these pages. Holmes had sufficient occupation to generate a modest income, but worldwide renown and financial security still lay some years in the future.

“Something will turn up, Watson,” my friend said, reaching for his pipe. “Something always does.”

“I do hope so,” I said, with feeling.

Moments later, Mrs Hudson entered. “You have another client, Mr Holmes,” said she.

“There, Watson,” said Holmes with an arch look. “What did I tell you? Show him up, my good woman. Let us see the cut of his jib.”

“The client,” said Mrs Hudson, “is already here.”

“Downstairs, you mean?” Holmes gave vent to a mildly exasperated sigh. “Well then, I repeat, show the gentleman up.”

“The client is no gentleman.”

“Gentleman, commoner, crossing-sweeper – I don’t care a fig about his social standing. As long as his coin is good, I will see him.”

“Mr Holmes,” said our landlady, folding her arms beneath her bosom, “perhaps I am failing to make myself understood.”

“There is no ‘perhaps’ about it, Mrs Hudson. You are being positively obtuse.”

At this point I intervened. “Holmes, can you not tell? Unless I miss my guess entirely, the client to whom Mrs Hudson is referring is none other than herself.”

The lady nodded, declaring, “Thank heavens one of you is not quite so slow on the uptake.”

“You, madam,” said Holmes, “are presenting yourself before me as a client?”

“Is that a problem, sir?”

He appeared to give the matter some thought, then shrugged his shoulders. “Not in the least. It comes as a surprise, that is all.”

“You can make time for me?”

“I believe I can squeeze you into my hectic schedule.”

“I shall pay the going rate,” Mrs Hudson said as she seated herself in the armchair to which Holmes directed her.

“You will do no such thing,” my friend countered sharply. “You are an excellent landlady. You are a cook of no mean ability. And you tolerate my less desirable habits with a forbearance a stoic would envy. I consider those qualities more than adequate recompense for whatever professional services I may now render you.”

“I realise that you sometimes have trouble meeting the monthly rent and that on those occasions Dr Watson takes it upon himself to pay the lion’s share.”

“Tut!” Holmes flapped a dismissive hand. “Let us hear no more of this. Either I work for you pro bono or I do not work for you at all. That is the end of the matter.”

“Very well.” From the pocket of her apron Mrs Hudson drew a folded letter. “It is this that has prompted me to seek your assistance. It came just now by the third post.”

She passed the letter to Holmes, who unfolded it with a peremptory shake of the hand and commenced perusal of its contents.

“I see,” he said ruminatively. “I see. Hum! And who is this Ada Biddulph? A friend of yours, obviously.”

“My oldest friend who, like me, lets rooms in her house in order to make ends meet.”

“Yes, I gather as much from her missive. The mention of a lodger is something of a giveaway. What a bind she is in, and no mistake. Neighbours and police all convinced of her culpability! Little wonder her tone is so agitated, not to mention her handwriting. She strives to maintain a neat copperplate throughout, yet her efforts repeatedly degenerate into scrawl and her lines are anything but straight. She is a woman, one may infer, for whom a good appearance is everything, and now her world is crumbling.”

“Quite so.”

“Holmes,” I said. I had discerned – as he had not – a distinct impatience beneath the composure of Mrs Hudson’s features. “Perhaps you would see fit to share with me the nature of the predicament in which this Mrs Biddulph finds herself.”

“Is this so that you might make notes, Watson, as I have seen you doing of late?”

“I simply would rather not feel excluded from the conversation.”

“But you are in the habit of making notes about my cases, are you not? I have observed you scribbling away in various journals and loose-leaf pads, during and immediately after the conducting of my investigations. Do not think that I have not. You seem to be treating me much as though I am one of your patients, in need of study and diagnosis. What plans do you have for these ‘case histories’ you compile? Do you perchance intend to publish them one day?”

“It is a possibility, I suppose. I have not given it a great deal of thought. I just find your methods intriguing and have begun enshrining them on paper for my own satisfaction.”

“But maybe also for posterity.”

“That remains to be seen. In the meantime, the letter?”

“Yes. Here.”

Holmes handed it to me with a wry smile. He was not wrong, in so far as I was indeed considering working up my notes on his cases into narratives. I had long harboured ambitions of pursuing a literary career, as a sideline to my medical practice. Holmes, who by then had been my companion and cohabitee for the best part of four years, fascinated me. His character and his talents were so unusual, so idiosyncratic, that I felt them worthy of analysis. In time, I would indeed settle down to publishing the accounts of his exploits that have since brought me a modicum of acclaim. It would be another three years, however, before the first of these, A Study in Scarlet, saw print.

I cast an eye over Mrs Biddulph’s letter. Following a brief salutation to Mrs Hudson, addressing her by her Christian name, the text ran thus:

I write to you in a state of some consternation, my hand trembling such that I can scarcely keep pen to paper. Lord, what torment the past twenty-four hours have been! What alarums and excursions I have had to endure!

It began with my discovery of Mr Niemand, dead in his sitting room. You know Mr Niemand, of course, the fellow to whom I am letting my basement. Lately from India, during the month he has been with me he has been a model tenant – not at all like that disorderly Bohemian whom you house under your roof and about whom you have had cause to grumble more than once.

I chuckled to see Holmes referred to thus, and my friend, fully aware which passage of the letter I had just scanned, shot me a look of reproof mixed with chagrin.

You can well imagine my horror, upon bringing down Mr Niemand’s breakfast to him yesterday morning in the basement flat, to find his body sprawled upon the floor. I knew at once, from a single glance, that he was deceased. The utter immobility of a corpse cannot be misidentified. It was the same with my husband. The sight of George sitting there in that armchair, quite dead, is etched in my memory, as fresh as if it were yesterday rather than five years ago. You can just tell, can’t you, when the soul has fled the flesh? It brings such a terrible stillness.

I turned tail and ran to summon the nearest constable, and soon my home was overrun with policemen. Amidst all the chaos – the prodding, the nosing, the peering – a consensus seemed to emerge. Mr Niemand had been poisoned. So said the ferrety-looking detective inspector who assumed charge of the case. I never quite caught his name. French-sounding. Lagrange, I think it is.

There was blood around Mr Niemand’s nose and mouth, you see, considerable quantities of it. I had not beheld this detail myself, since I had quit the room as soon as I realised he was dead, for fear that I might faint. The inspector told me also that Mr Niemand had egested the contents of his stomach rather violently. This I had been aware of, thanks to the smell in the room.

Imagine my shock when it became apparent that Inspector Lagrange – or whatever his name was – deemed me a likely candidate for being Mr Niemand’s poisoner. Although he did not come out and say it in so many words, his insinuations left me in no doubt that, not only had a capital crime been committed, but I was the chief suspect. I, after all, had prepared the meal which Mr Niemand ate the night before and which, by Lagrange’s presumption, had been laced with a lethal concoction.

You know as well as I do that I am the last person who could take the life of another. I appreciate that there are some who have cast aspersions upon me after George passed away. Certain of my neighbours hold the opinion that his demise was somehow my doing, for all that the doctor firmly pronounced the cause as a perforated stomach ulcer. Doubtless the inspector had been apprised of those rumours before he arrived at his conclusion. The local gossips would have wasted no time informing his constables, as they pursued their enquiries at other houses along the street. But I was not then a murderess and am not now!

All the same, a cloud of suspicion hangs over me, and Inspector Lagrange has constrained me to remain at home, on my own recognisance, and await further communication from him. Effectively, I am under house-arrest. A constable is stationed outside my door, ostensibly to discourage curiosity-seekers but really to keep an eye on me. I only hope I can prevail upon the fellow to let me take this letter to the postbox on the corner. I am sure, if I invite him to accompany me thither and back, that he will accommodate me.

I implore you, if you can, to help. I am at my wits’ end. I did not sleep a wink last night, nor have I eaten a scrap of food since yesterday. A man has died on these premises, in horrible circumstances, and I am innocent of any wrongdoing, and yet I am terrified that I may be held to account.

Yours in desperation, Ada

“The poor woman,” I said, returning the letter to Mrs Hudson, who nodded feelingly.

“You are convinced there is nothing to the neighbours’ assertion that Mrs Biddulph killed her husband?” Holmes asked her.

“Pure fiction,” Mrs Hudson replied with vehemence. “Baseless and slanderous tittle-tattle. But I know how it arose. George Biddulph was, I regret to say, a drunkard and a beast of a man. He would use Ada cruelly when there was alcohol in him and sometimes when there was not. She put up with it for years, with saintly fortitude, and when he died she shed few tears. For that reason, it was assumed by the locals that she might have had a hand in his demise. She did not mourn as a recently bereaved wife ought – for which, who can blame her? – and even though it was common knowledge that her husband used to beat her, folk still thought the worst of her for not being devastated by his abrupt passing.”

“What appalling hypocrisy,” I said.

“That is the tenor of the area in which Ada lives. Notting Hill is not what one might call the most salubrious quarter of London. I myself am loath to venture there after dark.”

“So Mr Biddulph’s death by natural causes was merely that – death by natural causes,” said Holmes.

“Not so surprising in a man fond of the bottle,” I said.

“And with such a choleric disposition too,” said Mrs Hudson. “The doctor was unequivocal in his verdict. Fatal blood poisoning arising from a perforated stomach ulcer, he said, and ruled that there was no suspicion of foul play. That, however, cut no mustard with Ada’s neighbours, who reckon she must have slipped George strychnine or some other such poison.”

“And now that her lodger, Mr Niemand, has actually died of poisoning,” said Holmes, “it would seem to bear out their beliefs about Mrs Biddulph.”

“Beliefs which Inspector Lagrange has allowed to infect his own reasoning,” I said.

“‘Lagrange’ sounds remarkably similar to ‘Lestrade’, don’t you think, Watson?”

“You are suggesting they are one and the same person?”

“By her own admission Mrs Biddulph did not apprehend his name clearly. She also describes him as ‘ferrety-looking’, which Lestrade undoubtedly is. Lagrange would appear to lack investigative rigour, and that too is a Lestradian trait, although one, amidst the plurality of Scotland Yard officials, not confined to him. All in all, the evidence points to the individual in question being our old friend and antagonist.”

“Mr Holmes, I need to know,” said Mrs Hudson. “Will you take the case?”

“I shall,” said Holmes, “unhesitatingly.”

“Thank you. That is a weight off my mind. I will write and inform Ada forthwith.”

“I think we can do one better than that. Watson? Gather up hat and coat. We are going to pay a call on our not-so-merry widow.”

“And I shall accompany you,” said Mrs Hudson. “Ada can surely do with seeing a friendly face.”

“My dear lady—” Holmes began, but a stern look halted him mid-protest.

“I shall accompany you,” Mrs Hudson reiterated in a manner that brooked no further refusal and from Holmes received none.

CHAPTER TWO

INIGO NIEMAND’S LAST SUPPER

Hansoms were in short supply, so we walked the couple of miles to Notting Hill, passing through the canal-threaded quarter of Maida Vale popularly known as “London’s Venice” and thence through Portobello and Ladbroke Grove. A late-afternoon fog had descended, dimming the sunlight to a shade of sepia that complemented the bronze and amber hues of the leaves, half of which still clung to the trees, the rest littering the ground. In Notting Hill itself the terraced houses seemed to huddle close together amidst the brumous haze, almost as though they were seeking out one another’s company for comfort, or else conspiring.

Ada Biddulph owned a brick-faced three-storey dwelling whose front door was reached by a short flight of steps. A constable stood on the pavement outside, hunched in his cape with the disconsolate air of one who would rather be anywhere else. Holmes showed the fellow his card, which was subjected to a wary, purse-lipped scrutiny.

“Inspector Lestrade can vouch for me,” Holmes said.

“I have heard him mention you once or twice, Mr Holmes,” said the policeman.

“Then, by your leave, we are permitted to enter?”

“To be honest, sir, I am under no instruction to deter legitimate visitors, only those that have come to gawp.”

Without another word Holmes rapped upon the door. Presently it was opened by a woman in middle age who regarded us through a pair of wire-rimmed spectacles with timid caution. Then her gaze fell upon Mrs Hudson, whereupon she at once gave a cry of delight. The two women knotted hands and embraced cordially, and there was much cooing.

Ada Biddulph was in appearance as unlike Mrs Hudson as it is possible to imagine. Where the latter was sturdy and doughty, the former was reed-thin and nervous-looking. It seemed a wonder that the two of them shared commonality, let alone were on closely amiable terms. Yet opposites attract, as the saying goes, and one need look no further than Holmes and me for proof of the adage – two men who were hardly cut from the same cloth but who had, for all our differences, forged a solid bond.

Once Mrs Hudson had made introductions and explained the nature of our errand, Mrs Biddulph invited us in. Soon we were settled in her parlour while she went to prepare a pot of tea, the revivifying qualities of which did much to dispel the chill that the foggy day had instilled within us.

Under interrogation by Holmes, Mrs Biddulph rehearsed the events of the previous morning. She told how she had taken breakfast on a tray down to her lodger, only to discover his body prone upon the sitting-room rug, arms outstretched, legs akimbo. His face was pressed to the floor, but what she could see of it presented a ghastly prospect, for it was reddened and swollen to a considerable degree.

“I set the tray down, somehow managing not to drop it,” said she, “and hastened back upstairs. You may think me a coward for that.”

“Not at all, madam,” said Holmes.

Mrs Hudson, who was sitting beside her friend with a consoling arm about her shoulders, expressed similar sentiments.

“The smell in that room was already turning my stomach and making me lightheaded,” Mrs Biddulph continued. “I did not want to pass out. That was my thinking.”

“The smell of emesis?”

She nodded. “Horribly pungent, it was. I collared the nearest policeman. After that, everything became a daze, as in a dream. A nightmare, in point of fact, once Inspector Lagrange started levying his none too thinly veiled accusations.”

“Lestrade, perhaps? I know almost every detective inspector in London and am unfamiliar with any Lagrange.”

“Does his name matter? But yes, come to think of it, it may have been Lestrade. At any rate, I have been trying ever since to maintain equanimity in the face of horrendous circumstances, but it is hard.” The pallor of the woman’s complexion and the sunkenness of her eyes attested to the truth of her statement.

“You are coping admirably,” Holmes assured her, “and it is my intention to dispel any shadow of suspicion that may have attached to you.”

“Can you do that?”

“I can make every effort. Would you be so good as to show us to Mr Niemand’s lodgings?”

Down a creaky uncarpeted back-staircase we went, the four of us, to enter a flat which consisted of a relatively spacious sitting-room with doors leading off to a small bedroom and tiny bathroom at the rear. The décor was plain and the atmosphere not as dingy as in many basement flats, for this one sat only partially below ground-level and the windows – particularly the large window at the front, which was part of a projecting bay shared with the storey above – let in a goodly amount of light.

Beyond the faint odour of digestive juices that lingered in the air, what was most notable about the place was its state of considerable disarray.

“The mess is the police’s doing,” Mrs Biddulph said. “Mr Niemand himself liked to keep things neat, but the police, in the course of their examinations, emptied out drawers, ransacked bookshelves, tossed papers around, and then left everything like this, all higgledy-piggledy and topsy-turvy. The only tidying they did was remove the rug upon which the body lay, and the body itself, of course, which they took out through the flat’s own front door using the rug as a makeshift stretcher.”

“I would rather a horde of rampaging Visigoths had trampled through the place than a cohort of Scotland Yarders,” Holmes remarked. “It will be a miracle if any viable clues remain. Yet we should not lose hope. While much has been overturned, much may also have been overlooked.”

So saying, he embarked upon one of his thorough and energetic inspections of a crime scene. He darted hither and yon across the flat, now standing on tiptoe, now going down on his knees, now crawling on all fours, and every so often emitting a gasp of exasperation or a murmur of intrigue.

All of this behaviour greatly bewildered Mrs Biddulph, patently enough that Mrs Hudson felt moved to off er her reassurance. “If there is something to be found, Ada, something beneficial to your situation, have no fear that Mr Holmes will find it. For all his eccentricities he is the sharpest man I have known.”

I myself was not persuaded that Holmes’s efforts would bear fruit. The chaos was simply too extensive. What order could he possibly derive from it?

Finally, after some twenty minutes, my friend stood erect, quivering somewhat, like a pointer that has caught the scent.

“This is a fascinating state of affairs,” he announced. “Fascinating. So much is missing here, so much that might have aided me in my deductions, yet what remains tells a singular story, one fraught with incongruities and inconsistencies. Mr Inigo Niemand was, I would submit, more than he purported to be. Mrs Biddulph, I recall you saying in your letter to Mrs Hudson that your lodger was ‘lately from India’. Do I have that right?”

“He told me he had been working in Calcutta as a secretary at the Imperial Legislative Council and had resigned his position in order to return to England. He had grown tired of the tropical climate, he said, and had moreover contracted a couple of diseases which, though not life-threatening, had left him in poor sorts. He hoped that after a few months of recuperation back home he might be well enough again to seek fresh employment. In the meantime he had a small sum in savings upon which to live.”

“Calcutta, eh?” said Holmes.

“I had no reason not to take him at his word. He was very tanned, and as for a weakened constitution, he comported himself with a marked fragility, not to say a reticence. He rarely left the house even on fine days, and when he did go out it was seldom for longer than half of an hour. He might manage to walk to the post office or to the newsagent to buy a paper, but that was it. Greater exercise than that seemed beyond him. His appetite was good, mind you, but then I am a dab hand in the kitchen, even if I do say so myself.”

“Your culinary accomplishments put mine to shame, Ada,” Mrs Hudson said.

“Mr Niemand did once suggest, jokingly, that I might like to use a little more spice in my recipes, but I imagine he had become accustomed to curries while abroad and found English cuisine bland by comparison.”

“This India connection is all very well,” said Holmes, “but I see no sign of it amongst Niemand’s belongings. What I have found is this.”

He ushered us into the bedroom and drew our attention to a figurine which lay half buried under scattered clothes. It was perhaps nine inches tall, was carved of some dark hardwood, and depicted a warrior-like individual with his head jutting forward and his tongue protruding to its root. Whorls were etched into his scalp, suggestive of curly hair, and in one hand he brandished a crudely rendered representation of a spear.

“Does that look Indian to any of you?” said Holmes. “It does not to me. I am no expert in the anthropological sciences, but I do not believe it to be the handiwork of a Hindu. On the contrary, I would wager good money on it being African in origin.”

“Some kind of fetish,” I hazarded.

“I would concur. The stance of this little fellow is aggressive, leading one to infer that he is a totem designed to ward off evil – although in that capacity it turns out that he was sadly deficient. Why would the employee of a company working out of India possess an artefact native to an entirely different continent?”

“Perhaps he picked it up on his journey home,” I said. “If he travelled by sea all the way, rounding the Horn rather than taking one of the partially overland routes, his ship would have docked at ports in Africa. When I sailed to England from Karachi aboard the troopship Orontes, there were stopovers for resupply at Mombasa, Cape Town and Freetown, to name but three.”

“For which reason the fetish, in itself, does not make a compelling argument that Niemand was not telling the truth. However, there are also these handkerchiefs to consider.” Holmes held up a square of linen. “Here is one. Observe the monogram embroidered in the corner. The initials read ‘B.W.’. There are three more handkerchiefs identical to this and none of any other nature. Why does a man going by the name of Inigo Niemand have handkerchiefs monogrammed with initials not his own?”

“What if they are heirlooms?” Mrs Hudson said. “Th ey are nice handkerchiefs. They must have cost a pretty penny. Perhaps he inherited them from a cousin, or a grandfather on his mother’s side. If they were in my family, I should not want them to go to waste.”

“Would one not unpick the stitching of the monogram, though, and have it replaced with one’s own initials?”

“Sometimes it is not possible. The unpicking may ruin the integrity of the cloth.”

“I bow to your expertise, Mrs Hudson. Nonetheless the anomaly piques my curiosity. For a third and final point of interest, the most significant of them all, let us return to the sitting-room.”

As we reassembled in the sitting-room, Holmes bent and extricated a scrap of paper from beneath the writing desk which occupied an alcove by the bay window.