7,31 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Writers of the Apocalypse

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

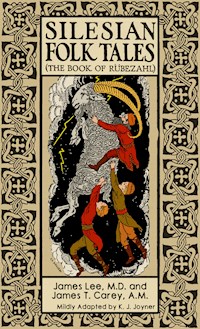

Long ago in the region between old Bosnia and Silesia there dwelled The Mountain Spirit, a mischievous yet warmhearted creature who loved his relationship with mankind. This collection of traditional folk tales, originally published in 1915, recount some of his encounters with various people - and how they were either punished or rewarded for their deeds.

Whether you are of Silesian descent or are simply curious about that ancient region of what is now the Czech Republic, if you enjoy folk tales then you're sure to appreciate the trickery of the mighty Rübezahl.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 157

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Silesian Folk Tales

The book of Rübezahl

by James Lee, MD and James T. Carey, AM

~*~

(Mildly) Adapted by K. J. Joyner

Silesian Folk Tales: The Book of RübezahlLee,James; Carey, James T.; Joyner, K. J.

With the original illustrations from the 1915 edition

New, adapted edition2016

Published by The Writers of the Apocalypse117 N Carbon Street, PMB 208Marion, IL 62959www.apocalypsewriters.com

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-944322-16-8ISBN Print: 978-1-944322-17-5

(Original) Introduction

The following tales, for the most part, have their scenes laid in Silesia and Bohemia. They are well known throughout all Germany, especially in the central and southern parts. They are folk tales in the highest acceptation of the term. For centuries they have come down in the shape of tradition from generation to generation.

Silesia, the land of their birth, has had an eventful history. Originally a part of Poland, it was drawn under the influence of the German king, Frederick Barbarossa, about 1163. Many names of places suggest that the original population was Celtic. For four centuries it was almost continuously under the domination of Bohemia. It was annexed to that country about 1472. It was finally added to Prussia by Frederick the Great. Bohemia derives its name from a Celtic tribe. It forms the border line between the German and Slavonic races. The geography and history of these countries are very interesting and will repay any reading and study that may be given to them.

Rübezahl, the hero of these tales, to use the words of a now forgotten writer1 of his adventures, “is a spirit prince and exercises supreme authority over all other gnomes in his district. He is superior to them in many particulars. What his real appearance is no one really knows. He can make himself so beautiful that Apollo is ugly in comparison.

On the other hand, he may, and he often does, assume an appearance so terrible that old women hurriedly mutter a fervent prayer, brave men take to flight, and young maidens sink in unconsciousness. His character is as changeable as his form.”

His better side is presented in this little volume, but many stories are told of the manner in which he took revenge on mankind for the great injury it inflicted on him and which eventually gave him his popular name.

“Imagine yourselves, my dear readers, seated on a wild winter night in a Silesian hut in the Riesengebirge2, several thousand feet higher than the surrounding valleys, with snow, fathoms deep, everywhere. The wild storm rages through the desolate mountains. Within, however, everything is warm and comfortable, and as the matrons and maidens busily spin, in fancy, you can listen with pleasure to their tales of the mighty Mountain Lord."

These tales have been carefully adapted for the young readers of the elementary schools, and it is to be hoped that these will derive as much pleasure from their perusal as do their young friends in the different countries of Central Europe.

There, Rübezahl is known as the hero of many a merry prank, and though his character is not entirely free from the charge of spiteful actions, he is, on the whole, a personage with whome it is well that our young folk should become acquainted.

Much has been written about him, though not in English.

In fact, with an exception or two, this is the first collection of Rübezahl to be placed before the American reading public.

The general tone is quietly ethical, and the youngest reader should easily perceive the valuable lessons to be derived from them.

James Lee, MD, andJames T Carey, AM

(Modern) Introduction

I'm putting this book back on shelves for the general public in an overall effort to keep it from being lost. Sure it comes from the public domain and there is at least one archive that houses it, but that doesn't mean what we've preserved won't somehow be lost someday.

I have also very sparsely updated or tightened some of the language. I suppose you could call this adapting the book, but I prefer to call it "mildly adapting". Of course I did it to make the book easier to understand for the modern reader, but I had to be careful lest I actually change the stories themselves. This book remains an antiquated read in many respects as a result.

A modern day reader should take note that these stories are from a different generation. At least one story raised my eyebrow at what my modern mind perceived an injustice.

In my youth these sorts of stories, with this very archaic language, would have been delegated to children. A lot of people wouldn't do that today, but maybe they should. Okay yes, the drawback to me reading so many old things is I once got bad marks on a college paper for trying to "fake it" using "Middle English" when the truth is I really do speak this way. But this drawback means something very important: not all of my education depended on being at a desk, bored to death. I learned a lot of things on my own. And I had fun doing it.

So if nothing else, read this to your children. Act out the parts. Have fun with it. That's what these stories were originally for, you know.

K. J. Joyner

Table of Contents

(Original) Introduction

(Modern) Introduction

Table of Contents

Rübezahl In The Beginning

The Wagoner

Tailor Zwirbel

The Flute Player

Three Students

Little Peter

Farmer Veit

The Horse Dealer

The Braggart’s Punishment

The Mountain Meadow

The Magic Peas

Mother Ilse

The Journeyman

The Wonder Staff

The Mandrake

The Master Of Horse

Beautiful Susan

(Original) Epilogue

Rübezahl In The Beginning

North of the Czech Republic and the South-west of Poland, as part of the Sudetes mountain system, there extends a lofty range of mountains known as the Riesengebirge. Long ago, this area was between two countries, Silesia and Bohemia. Times change and the land often will change with it. Which is how and why Rübezahl begins his tales with us, mere humans.

The name, Giant’s Mountains, recalls many legends concerning Rübezahl, who for centuries, according to these legends, held sway there and made the neighborhood the theater of his many wonderful and frightening exploits.

On the earth’s surface this prince of the mountain spirits possesses limited territory, a few miles principally on the rocky heights and surrounding country. Beneath the earth’s crust his real dominion begins, and it stretches downward to the center of the globe. At times it pleases this ruler of the underworld to wander through his realm, to inspect the treasure chambers of gold and silver, to oversee his subject spirits and other ghostly creatures, and to keep them at work.

During these times when Rübezahl throws off all cares of state, he comes to the earth’s surface and lives for a while on the Riesengebirge. In playful wantonness he makes fun and mockery with the children of men. Friend Rübezahl, be it known, is peculiarly composed, peevish, impulsive, violent, malicious, fickle, though at times generous and sympathetic. Like an egg in boiling water he is soft and hard at two successive moments; one day, the warmest friend, the next day, strange and cold; in short, full of contradictions, and acting, generally, according to the impulse of the moment.

Many, many centuries ago, and long before either Silesia or Bohemia (or the Czech Republic for that matter) was inhabited, Rübezahl wandered around the wild mountains. He took pleasure in inciting bears and wild ox3 to deadly combat, or in driving them over steep cliffs into the valleys below. When he grew tired of hunting, he would return to the underworld and remain there until again the desire would overmaster him to enjoy the beaming sun and the beauties of the surface.

One can imagine how astounded he was on one of these occasions when, looking down from the summit of the Riesengebirge, he found the landscape changed. The once gloomy, impenetrable woods had disappeared and in their place were fruitful fields where rich harvests were ripening. Between budding fruit trees appeared the thatched roofs of comfortable cottages out of whose chimneys blue smoke curled upward. Here and there on the summit of a hill was a solitary watch tower so the people could keep a lookout for danger. Sheep and cattle grazed on the verdant meadows and the sweet tones of the shepherd’s flute could be heard in the distance.

The changes delighted him and he was not displeased with the farmers, although they'd settled there without his permission. He decided to leave them in undisturbed possession of the property, as a good-natured farmer allows the twittering swallow or troublesome sparrow to build in the projecting eaves of his barn. He even wanted to become acquainted with men, and to get used to talking with them.

Rübezahl has the magical gift of being able to change shape. He can change into anything he wants, although when it comes to man he usually assumes the shape of a fellow human. So he took the form of a peasant and found a job with the nearest farmer. Everything he did prospered, and Rips, as he called himself, was soon recognized as the best workman around. But his employer was a spendthrift. He was always spending money and squandered the profits of his faithful laborer, giving Rips but little thanks for his hard work. On this account Rips left him.

His next job was with a shepherd. Rips carefully watched over the flocks of sheep and conducted them to the hillside pastures where rich juicy grass was found in abundance. The flocks thrived, even flourished, under his care. No sheep fell from the overhanging cliffs nor were any eaten by wolves. His master, however, was a greedy miser who poorly repaid his faithful helper. He sometimes even stole the best ewe from his own flock and deducted the price from Rips’s wages.

Later on Rips took service with the judge of the village. He became a terror to criminals, and he was very enthusiastic enforcing the law. But the judge was corrupt and decided cases according to his interests and secretly even mocked at the law. When Rips refused to be a tool of injustice he was thrown into prison, from which he escaped in the usual way to spirits, through the keyhole.

These first attempts to get to know mankind in no way increased his love for them, as I'm sure you can imagine. Annoyed, he returned to the summit of the Riesengebirge, looked down over the smiling fields, and wondered how mother nature could shower so many gifts on such thankless creatures.

There was a petty king in the country of Silesia, and he reigned in the area bordering on the Riesengebirge. He had a beautiful daughter named Emma, as kings usually do. The Mountain Lord once saw her as she and her servant maidens were taking a walk.

Immediately he fell in love with her. He went to her father’s court and asked for her hand in marriage. He represented himself as a powerful prince from the Far East, just then on his travels. Using his magic, he put on a lavish display of wealth and glory to color to his statement.

Emma's father the king was not against the match, but Emma, who was already engaged to Ratibor, the son of a neighboring prince, positively refused.

Not to be discouraged, the Mountain Lord used his magic and created a palace on the mountains just for the Princess Emma. Then he used his magic to steal Emma away, transporting her to it. Here she was to live as his prisoner until she agreed to marry him.

To keep her from getting lonely, he gave her a magical wand. With it she could change turnips into anything she wanted them to be. She changed a basketful of turnips into people to talk to or pets to care for. She lived pleasantly like this for a long time, surrounded by her counterfeit companions. But she never stopped looking for a way to escape.

After a while she hit on the following plan. The Mountain Lord had planted a large field of turnips so that she should always have a plentiful supply. One day Emma asked him to count the number of plants that had sprouted. She told him she had finally decided to become his wife and needed to know how many people would be coming to her wedding. She said she was going to give life to every turnip in the field. However, she also warned him to be accurate in his count because even a single mistake would change her mind.

Beside himself with joy Rübezahl began his allotted work. He skipped around among the growing turnips as nimbly as a sparrow picking up grains of wheat. Owing to his zeal, he was soon finished but to make sure he had done it right he counted again.

He found to his annoyance that the two counts didn't agree. This meant he had to count a third time. After the third count, there was still a difference in totals. He had been so excited to marry Emma and so preoccupied thinking about it, he had missed his count each time. This meant he had to count the turnips again!

While the simple-hearted Mountain Lord was counting and recounting the turnips, Emma made her escape. Using the wand, she changed a turnip into a magnificent steed. Riding it, she fled over hill and dale until she reached her father’s land.

Since that time the people of Silesia in mockery called the Mountain Lord Rübenzahler, turnip counter, or Rübezahl for short. To call him by this name is always sure to rouse him to anger, as we shall learn in the course of our stories.

The Wagoner

One day, long ago, Rübezahl was traveling by foot on the highway to Hirschberg.

A wagoner, that is to say someone driving a horse-drawn wagon, was passing by. The wagoner only a light load in his wagon, so journeyman Rübezahl asked for a ride. In return for the favor he offered to pay what little money he had.

The surly wagoner angrily snapped his whip and said gruffly, “I'm not overanxious for a traveling companion, neither are my horses. They have enough to do dragging an empty wagon over these wretched roads. Still, give me the money before you get in. I'll take you, although I don't really trust strangers.”

The lad drew out his purse and gave him four groschen, which was the coin back then. Then the journeyman answered laughingly, “Your words should offend me, but I'm willing to swallow the bitter pills; they won't give me a stomachache." He got into the wagon and sat on the hay which lay in the bottom. The wagon moved slowly forward along the deep and uneven ruts.

They'd gone only a short distance when the horses suddenly stood still. The wagoner shouted at them, he cracked his whip, and he even beat them. The horses wouldn't move from the spot. The wagoner angrily looked to see what was wrong with the wagon or harness. He found everything in good condition and was unable to understand the obstinacy of the horses.

“I see,” said the journeyman, as he got out of the wagon, “that I can go faster on foot than I can with you and your horses. Give me my money back. I can get supper and lodging for it at Hirschberg, and my feet can carry me that far.”

“What is wrong with you, you fool?” the wagoner said mockingly. “What’s paid is paid. I didn't force you to get into my wagon and I don't force you to get out. You do so of your own free will. You may keep your seat if it suits you. The balky horses will soon go on again.”

But the animals stood stock still, as if made of stone. They didn't even move their ears. Flies gathered around them to bite them, and the horses didn't even switch their tails to shoo them off. The wagoner took a large club and beat the horses in blind rage. After stopping for breath, he was about to renew his attack when both animals fell suddenly to the ground as if dead.

“A wicked spell rests on the horses,” he murmured, and looked suspiciously at the journeyman, who was now sitting by the roadside to eat his frugal lunch. “Don’t you also think that the horses are bewitched?”

“How do I know?” was the answer. “Let me help you.” The journeyman got up and slung his wallet over his shoulders. He went to one of the horses, unhitched it, and patted it coaxingly on the neck.

The horse suddenly sprang to its feet and the lad leaped upon its back. They galloped away at great speed. As a farewell he waved his hat to the astonished wagoner and cried out laughingly, “I thank you for the seat in your wagon, but I find myself much better off on your horse.”

The wagoner, who now knew that Rübezahl had played him a trick, ran to the nearest village, told the people of his adventure with the Mountain Lord, and requested the landlord of the inn to lend him horses to bring his wagon to Hirschberg. The man willingly complied, and accompanied him with many others who wanted to witness the affair with their own eyes.

As they approached the wagon they heard a cheerful neighing and saw the remaining horse standing erect, pawing the ground with his forefeet as if to greet his master. Fresh and in good condition, the horse stood there and seemed only to await orders to set the wagon in motion. The wagoner was delighted that at least one horse was left, and he did his best to forget the loss of the other.

From that time the sulky wagoner became friendly and pleasant to everyone. There was always a seat for any old woman or fatigued traveler that he chanced to meet on the road. “For,” he would say to himself, “who knows but it may be Rübezahl again?”

Tailor Zwirbel

In order to test