7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Serie: Six Stories

- Sprache: Englisch

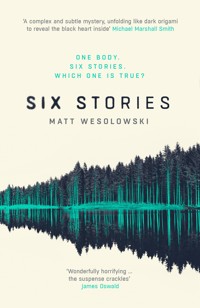

Elusive online journalist Scott King investigates the murder of a teenager at an outward bound centre, in the first episode of the critically acclaimed, international bestselling Six Stories series… For fans of Serial 'Bold, clever and genuinely chilling' Sunday Mirror 'Haunting, horrifying, and heartrending. Fans of Arthur Machen, whose unsettling tale The White People provides an epigraph, will want to check this one out' Publishers Weekly 'Wonderfully horrifying … the suspense crackles' James Oswald 'A complex and subtle mystery, unfolding like dark origami to reveal the black heart inside' Michael Marshall Smith ________________ One body Six stories Which one is true? 1997. Scarclaw Fell. The body of teenager Tom Jeffries is found at an outward bound centre. Verdict? Misadventure. But not everyone is convinced. And the truth of what happened in the beautiful but eerie fell is locked in the memories of the tight-knit group of friends who embarked on that fateful trip, and the flimsy testimony of those living nearby. 2017. Enter elusive investigative journalist Scott King, whose podcast examinations of complicated cases have rivalled the success of Serial, with his concealed identity making him a cult internet figure. In a series of six interviews, King attempts to work out how the dynamics of a group of idle teenagers conspired with the sinister legends surrounding the fell to result in Jeffries' mysterious death. And who's to blame… As every interview unveils a new revelation, you'll be forced to work out for yourself how Tom Jeffries died, and who is telling the truth. A chilling, unpredictable and startling thriller, Six Stories is also a classic murder mystery with a modern twist, and a devastating ending. ________________ Praise for the Six Stories series 'A genuine genre-bending debut' Carla McKay, Daily Mail 'Impeccably crafted and gripping from start to finish' Doug Johnstone, The Big Issue Matt Wesolowski brilliantly depicts a desperate and disturbed corner of north-east England in which paranoia reigns and goodness is thwarted … an exceptional storyteller' Andrew Michael Hurley 'Beautifully written, smart, compassionate – and scary as hell. Matt Wesolowski is one of the most exciting and original voices in crime fiction' Alex North 'Original, inventive and dazzlingly clever' Fiona Cummins 'It's a relentless & original work of modern rural noir which beguiles & unnerves in equal measure. Matt Wesolowski is a major talent' Eva Dolan 'Endlessly inventive and with literary thrills a-plenty, Matt Wesolowski is boldly carving his own uniquely dark niche in fiction' Benjamin Myers 'Disturbing, compelling and atmospheric, it will terrify and enthral you in equal measure' M W Craven 'Readers of Kathleen Barber's Are You Sleeping and fans of Ruth Ware will enjoy this slim but compelling novel' Booklist 'A relentless and original work of modern rural noir which beguiles and unnerves in equal measure. Matt Wesolowski is a major talent' Eva Dolan 'With a unique structure, an ingenious plot and so much suspense you can't put it down, this is the very epitome of a must-read' Heat 'Wonderfully atmospheric. Matt Wesolowski is a skilled storyteller with a unique voice. Definitely one to watch' Mari Hannah

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 394

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

Six Stories

MATT WESOLOWSKI

—So do we pass the ghosts that haunt us later in our lives; they sit undramatically by the roadside like poor beggars and we see them only from the corners of our eyes, if we see them at all. The idea that they have been waiting there for us rarely crosses our minds. Yet they do wait, and when we have passed, they gather up their bundles of memory and fall in behind, treading in our footsteps and catching up, little by little.

Stephen King – Wizard and Glass

—Mountains overawe and oceans terrify, while the mystery of great forests exercises a spell peculiarly its own. But all these, at one point or another, somewhere link on intimately with human life and human experience.

Algernon Blackwood – The Willows

—Says milord to milady as he mounted his horse / Beware of Long Lankin that lives in the moss

Northumbrian/Scottish Murder Ballard

Contents

Scarclaw Fell 2017

I recognise this bit of woodland. This recognition ignites a little ember of joy inside me, a sense of accomplishment. The more I come out here, the more familiar with it I get. The trees glaring down with their familiar, pinched faces.

When I first met this land, it overawed me, just an unrelenting mass; disorder. There was no way of straightening it out. The woods just sort of jump at you from the dark; all those trees filled with croaking, fretting birds, the buckled heads of ferns that slap lazily at your shins as you pass through.

At first, I wondered if I should call in the bulldozers, get it swept away; just like Dad did with that Woodlands Centre. Now I’m glad I didn’t. In a strange sort of way, these woods are starting to become beautiful. Thinking this fills me with a horrible, leaden feeling; it’s the last thing that should enter my mind. It’s not proper. Yet the tiny pockets of spiders’ webs, each holding a single raindrop, and the peppering of gorse flowers on the fell-side tell me otherwise.

There’s magic here between the trees.

In my own way, I am beginning to understand this land. Its utter indifference to those who dwell here. Like the rest of us, these woods crouch in the shadow of the fell, which rears up in the distance; a cloud-crested wave of blackened scree.

Scarclaw Fell. It sounds like something from Game of Thrones.

I stop in a natural sort of clearing in the trees. I’ve been walking for ten minutes, now, and I can barely see the building behind me.

Dad was overjoyed when he finally got that place built on the site of what was once the Scarclaw Fell Woodlands Centre. Outside its front door, there’s a brass plaque. I fought tooth and nail with Dad about the new name: ‘The Hunting Lodge’. It just sounds so … twee. I guess he wanted to sweep away everything that had happened here before.

Dad filled The Hunting Lodge’s bookshelves with these tatty, leather-bound volumes. Something for the tourists to look at, though I doubt any of them ever read them. I’ve been looking through them recently. Their pages are thick, the yellow of old bones. The smell of pipe tobacco rises from them: like the ghosts of things past.

That’s what I do when I’m out here: I chase old ghosts. Stir up shadows. Think.

Sometimes I wonder what I am, what part I play in this whole mess. Am I, Harry Saint Clement-Ramsay, just another Dr Frankenstein, grubbing the dead up out of their graves to try and heal some old wound?

Should I have even agreed to be interviewed at all? Should I have agreed to wake the dead? Will my words destroy the peace that has taken twenty years to fall on Scarclaw Fell?

He wore a mask.

Just a white thing, the features of which jutted out from beneath his hood. Cheeks and a nose in pale plastic. A forehead that curved like a skull.

It should have been comical. Like the masks that crusty lot wear when they’re railing against the multinationals. But I was scared.

When he pulled up at the gate of the Mayberry Estate, we watched him from the security box. We had all his emails printed out; months of them – begging, pleading, promising. I was fully expecting a Hummer, blacked-out windows and all that. He was famous on the internet wasn’t he?

So the Ford Ka with a rash of bugs across its bonnet was the last thing we imagined he drived. Tomo rang my phone. I answered and left the line open, slipped it in my pocket. Tomo put his on speaker. We’d practised this. The code line was, ‘Did you try the farm shop on your way here?’ Not very original, but it would take the lads less than a minute to get from the security box to the gate if I said it.

Wait till he gets close, I thought, wondering if I could go through with all this. If the other chaps hadn’t been nearby, on guard, then I don’t know what would have happened. Maybe I would have bottled it; bowed out.

He had warned me he was going to wear the mask. When I searched online for him, I read all about it, sort of understood why he wore it. Yet when he stepped out of that car, I nearly said fuck it, no way. Nearly turned around and closed the gate. If he wasn’t even going to show his face … He could have been anyone.

I suppose that was the point.

I was scared. But I wasn’t going to show him that, was I? Justin had a shotgun. I don’t know if it was loaded. Tomo had a knife, still sharp from the packet. They were there to protect me. But in some way it was like they were defending the memory of that night twenty years earlier. The memory of what we saw. The memory of what we found.

The chap in the mask got out of his car and someone I didn’t recognise as myself walked over and shook his hand; that same someone betrayed no fear. I thought I could hear a smile in his voice.

He could have been snarling, scowling, mouthing profanities, hating the bones of me behind that mask. I’ll never know.

He thanked me. We got in my car. He clipped a microphone to my lapel and turned on the recording device.

Then we talked.

I stop in the clearing and pour tea into the cup of my flask. Everything is damp and I don’t want to sit down. It’s a cliché I know, but you never really stop and listen to silence, do you? I have started to listen when I’m here, beneath the branches. When I first started coming out, I used to wear headphones, one ear-bud in my right, my left empty.

The woods aren’t silent, not really; if you stand and listen there’s all sorts going on: rustlings and chattering; when it rains, the sound of the leaves is a cacophony of wagging green tongues; in the mornings the indignant back-and-forth clamour of the birds is almost comical.

I’ve not come out into these woods at night. Not for a long time, anyway.

The last time I walked here in darkness was nearly twenty years ago – it was me and Jus and Tomo. That was the night we found him. That boy. It was where the woods begin to thin, where they turn upward towards the bare back of the fell; where the path turns to marsh.

I think I don’t like silence because, when it falls, that scene begins its loop.

Nearly twenty years, and what happened that night, what we found out there, still doesn’t fade.

The man in the mask said he understood that; said he understood some ghosts never die. I think that’s what finally got through to me, and to Dad. If anything, he said, telling him what happened might help.

Help.

That’s not a word I’d have ever expected when it came to us. People didn’t think the Saint Clement-Ramsays needed help. Of course we didn’t; we had money, right? Who needs help when you’re rich?

Twenty years ago, Scarclaw Fell Woodlands Centre was still standing. The Hunting Lodge wasn’t even a concept; not yet. All of it – the woods, the fell itself, the Woodlands Centre – was Dad’s though. And the toilets and the showers still worked, so we just thought ‘sod it’, me Tomo and Jus. We left our cars sitting in puddles on the track leading up to the centre.

The Woodlands Centre back then was an awful, seventies block, all MDF and lino. It had a smell: steam, soil, warm cagoules; and in the kitchen the reek of veggie sausages and fried eggs. There was a spattering of muddy boot prints around the doorways; fold-up chairs, cobwebs in the corners, painted metal radiators. Someone – the Scouts or the Guides, one of the groups that used the Woodlands Centre – had made a frieze on the far wall in crêpe-paper: ‘Leave nothing but footprints – take your litter home’. A smiling badger beneath it. One of its eyes had come off and there was a tight scribble of black biro in its place.

To be honest, that first day in August 1997 wasn’t much fun. Me and Jus and Tomo were, what, all twenty-one or twenty-two-ish? It was chucking it down so the three of us sat in that long dining-room area, drank beers and played fucking Monopoly all afternoon. We ended up pretty trolleyed, just getting on each others’ nerves. We were all hungry and no one wanted to start cooking; but Kettle Chips and dips don’t fill you up. We were stupid, stupid city-boys. There were no takeaways around here and no one was sober enough to drive into the village or look for a petrol station. Jus pulled out some vintage whisky. That meant we’d drink till we were sick; be asleep by nine, with the rush and chatter of the trees haunting our dreams as we snored.

If only it’d ended like that.

I finish my tea, scatter the dregs into the undergrowth. Dawn begins to swell, her light expanding over the woodland. I turn toward the cloak of branches and brambles, and press on. That’s what we did back then – went off the beaten track. We were so wasted and it was so wet, we couldn’t even see a track, beaten or not.

I take another look back and the light in The Hunting Lodge window is still visible. I try to imagine what the Woodlands Centre looked like to that boy back then. This is the way he came, back in 1996. Through the branches, I don’t imagine it looked much different: a light in a window; the promise of warmth, four walls.

I keep going, plunging into the wood. You only have to be careful where you step when the ground starts sloping upward. There are signs now, but there weren’t back then. This was the way they came back in ’96, I’m sure of it: a couple of miles north-west of The Hunting Lodge (or the Woodlands Centre, as it was back then) there’s a sort of natural path between the trees. I follow it.

As I walk, there’s a little pull of nostalgia inside me: a longing. As if some little part of me, some thread, has caught on the memory.

Like I have become part of everything that happened here.

Which, in some ways, I suppose is true.

Episode 1: Rangers

—Dad bought up all the land round there just before … before it happened. I mean, literally, it was a few weeks.

Then the shit-storm descended.

Oh, terribly sorry … am I allowed to swear on this?

This is the voice of Harry Saint Clement-Ramsay; Harry’s the son of Lord Ramsay, owner of the land around Scarclaw Fell. Owner of the fell itself.

Scarclaw Fell: For those old enough to remember, that name has a certain resonance.

These days, that resonance is largely silent.

Meeting Harry in person is somewhat of a breakthrough, to say the least. The Ramsay estate has not acknowledged my emails or letters for months. I actually thought we might fall at this first hurdle. Indeed, without Harry, this podcast would lose significant authenticity; become just more speculation about what happened that day in 1996. The teeth of a rake through the long-dry earth of an old grave.

It’s been twenty years since the incident and the Ramsays have been consistent in their refusal to speak about it to anyone.

Until now.

Suited and booted, rosy-cheeked and athletic, Harry looks as if he’s from fine stock. As a person, he’s affable, but guarded. He reminds me of a politician visiting the proles in the lead up to an election. Every word is chosen with precision.

When it comes to Scarclaw Fell, Harry is evasive – careful with what he says. And to be honest, I don’t blame him.

—I think Dad was going to get all the old tunnels – the mineshafts and what have you – filled in. Then he was going to try selling it – to one of those developers, you know? For log cabins, fishing holidays or something? But … I guess it was too much of a job. And after what happened, the impetus just … wasn’t there anymore. And it’s like a bloody rabbit-warren under the fell – all the fissures and hidden pits; and that’s before you take into account the bogs and marshes and stuff where they … where we … well … you know. It’s a bloody death trap. Christ knows why they were even there in the first place, right? I mean, who would go there for fun?

Before the events of 1996, Scarclaw Fell was largely unknown. And today, most people have forgotten its name once more; despite that almost-famous photograph on the front of The Times; the hook-like peak curling through the clouds behind a spectral sheen of English drizzle. Most people have forgotten the name Tom Jeffries too.

Maybe that’s about to change.

—Sometimes I wonder how things could have been different. If dad had called the contractor an hour before he did, they would have come out and knocked the place down – repaired all the fences and the signs, got in some proper security to keep people away and none of this would have happened. An hour and dad could have said, ‘Sorry, it doesn’t matter how long ago you booked it, things change.’ That would have been that. I wouldn’t be talking to you now.

Just one hour – and a boy is dead.

Face down in the marsh. Someone’s son; someone’s grandson.

He was only fifteen, wasn’t he?

Christ.

Welcome to Six Stories. I’m Scott King.

In the next six weeks, we will be looking back at the Scarclaw Fell tragedy of 1996. We’ll be doing so from six different perspectives; seeing the events that unfolded through six pairs of eyes.

Then, as always, it’s up to you. As you know by now, I’m not here to make judgements. I’m here to allow you to do that.

For my newer listeners, I must make this clear: I am not a policeman, a forensic scientist or an FBI profiler. This isn’t an investigation or a place I’m going to reveal new evidence. My podcast is more like a discussion group at an old crime scene.

In this opening episode we’ll review the events of that day; introducing you briefly to the people present. We’ll be hearing, not just from Harry, but also from one of the others who was directly involved; who was there; who knew Tom Jeffries personally; and for whom the shadow of what happened on that day in 1996 still remains, like some malevolent, unshakable stain on their life.

We will look back on what is, to some, a simple, open and closed case – a tragedy that could have, and should have, been avoided. To others, though, it is an enduring and enthralling mystery, to which there are no clear-cut answers.

At least not yet.

OK, now for a little bit of history. Buckle up, I’ll be brief.

The fell itself rises from some of England’s most beautiful countryside; Northumberland, north-east England. Scarclaw Wood was once an old glacial lake, filled with sand and gravel; the fell – a standstone escarpment – is now classified as an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. There are several Iron Age cairnfields on its higher ground and the remains of scattered farmsteads on its slopes. Evidence of standing stone rings and Neolithic burial sites only add more layers to the landscape. The summit of the fell curls in a hook shape; as if something has taken a colossal bite out of its base. This is presumably the reason why Scarclaw has its name. Like much of Northumberland, inscrutable ‘cup and ring’ artwork decorates the rocks on its lower slopes.

Beneath the fell’s higher ground is a complex network of lead mines that date back to the fifteenth century. They’re all abandoned now, shut down in the 1900s due to subsidence. There were attempts to reopen the mines in the 1940s, but these were unsuccessful. Most of the tunnels beneath the fell have collapsed; and the resulting hollows and the weakened surface havecreated strange hybrid marshes and traps: half man-made; half claimed by nature. To attempt a walk across the marshland of Scarclaw Fell is to dance a jig with death himself. Without warning, the ground could simply swallow you up. Yet it is not only the marshland that is a danger to the unwitting; the majority of the mine’s ventilation shafts have long been obscured by nature, so they are now great fissures lipped with moss and heather. The only signs of what they were are the remnants of the decrepit fences erected long ago. Visitors to the woods and the fell are advised to stay on the paths. Large sections were fenced off long ago, but there is still danger underfoot on Scarclaw Fell.

Amongst this no-man’s land of reeds and marsh grass stand the remains of an engine house: a pale, crumbling tower encrusted with moss, and a wall with a single window; the only remnants of a remote hamlet.

—I don’t know what happened to that boy … I really have no idea. None of us do. How the police never found his body is just bloody … ludicrous though, isn’t it? A bloody year.

Harry and I record the interview in his car, in the driveway of Lord Ramsay’s Mayberry Estate. He assures me that is father is away and tells me that it’s probably futile trying to get even a statement from him.

—We don’t talk about it, Dad and I; not anymore. Best to leave these things buried … Oh gosh, I’m sorry … poor choice of words, but you know what I mean, yeah? Dad still blames himself for what happened up there, but what could he have done? There were signs already, they knew what was up there, didn’t they? They’d stayed there hundreds of times before. Hell, it was that lot who had insulated the place. They did it one summer; climbed underneath in those white decorators’ overalls and nailed a load of polystyrene to the underside of the floor. Mad, isn’t it? I mean, it was nothing more than a glorified barn.

It wasn’t just them that used the place. We hired it out to Scouts, Girl Guides, climbers, canoe-ers … canoe-ists? … speelenkers … spelunkers? Those guys that go climbing down holes … As I say, I’m not an outdoorsy type. They all knew what the dangers were.

Harry’s talking about the Scarclaw Fell Woodlands Centre; a self-catering, single-storey accommodation centre that was far more advanced than the ‘glorified barn’ he calls it. When it still stood, it had five dormitories with about thirty beds, gas central heating, a fully equipped kitchen, toilets, showers, the lot.

Situated at the very base of the fell, about five miles through the forest tracks off the A road, the centre was an L-shaped building with a car park and a telephone line. The centre was hugely popular. It was quite a distance from the danger of the mines and had plenty of picturesque walks and a river nearby. If you didn’t want to hire out the building, you could camp in its grounds. According to the one remaining logbook, it was fully booked all year round. Climbers, walkers, canoeists, spelunkers, even Scouts and Guides all used the Woodlands Centre regularly. And there are no records of any serious accidents occurring on the land around Scarclaw Fell in the last thirty years. Presumably the danger signs did their job.

Lord Ramsay acquired the land around Scarclaw Fell after what happened in 1996. The purchase was an ongoing battle that raged for several years between with Lord Ramsay, the local authority, the National Trust and the co-operative of groups that had used the centre. This battle is irrelevant to our story; but suffice to say, money conquered all, Scarclaw Fell became part of the Ramsay estate, the centre was levelled and most of the fell was fenced off. But we’re straying from the point. Back to Harry.

—The environmentalists threatened to jump all over Dad’s case if he changed things at Scarclaw. Don’t get me wrong, he was going to make it nice! But he said he’d have to drain a lot of it … the marshes … to make the holiday lets; and that was a problem – habitats and stuff. Newts, frogs and other slimy things no one cares about till they’re suddenly ‘endangered’. Those old mineshafts were the main problem, though; they had some rare bats nesting in them, didn’t they? Bats are alright I guess … but they’re a bloody legal nightmare, so I think he eventually just thought ‘sod it’ and left it all alone.

—Did your father ever visit, go to the Woodlands Centre itself, have a look around? Before what happened, I mean.

—He may have, I don’t know. It wouldn’t have made much difference to be honest. Dad’s like a bloody Rottweiler with a bone once he sets his mind to something, you know?

Harry and I talk for a while about the legal wrangling to purchase the land. I ask him a few times why Lord Ramsay wanted Scarclaw so much, but I don’t get a straight answer. Maybe he wanted some new hunting land, for grouse shooting, deer stalking, something like that? Parts of the land were, in fact, created as hunting parks around four hundred years ago. The ancient woodlands are a lingering testament to this. What I do know is that Lord Ramsay seemed to have underestimated the appeal of the land. Even after the tragedy; the fight for Scarclaw Fell went on for a long while.

Maybe, because Harry’s aware that this podcast will be listened to by millions, he is simply saving face – for his father, his family, I don’t know. Eventually, though, I have to broach the subject we’ve both been avoiding; circling each other like a pair of tigers.

—It was you, Harry, who found him, wasn’t it? You found Tom Jeffries’ body?

—Yeah … yeah … I found him…

OK, so I could have phrased it better, but there’s something about talking to people with Harry’s wealth and clout that makes me a little flustered: it’s that unshakeable confidence they exude, I just kind of blurt things out. For a few moments he looks at me and I think he is going to ask me to leave. Thankfully, he goes on with an unflappable air that I have to admire. Stiff upper lip and all that.

—Legally, I can talk about it now. Now that the case is officially … ‘cold’ is it called? Resolved? That’s not to say I want to, you understand. But I will, because … I don’t know, maybe it’s cathartic or something, yeah? And you’re not a journalist…

Harry’s very aware of what will happen when Six Stories airs, he’s not a podcast fan himself but he knows just how popular these things are. He tells me he’s heard of Serial and he’s aware of the potential thousands, possibly millions that will hear Six Stories worldwide. He asks me about whether I think the media will turn to him, or even his father, for answers. Lord Ramsay is an old man, he says; he doesn’t need that. I tell him I don’t know what will happen when Six Stories airs, that I can’t make any promises. It seems he appreciates my honesty. He says he’ll tell me what he told the police before he has to go.

—So, yeah. OK. So me and a few of my mates are out there, yeah? Having a little recce of the place, a bit of a mission, if you know what I mean?

Harry’s talking about the lower regions of the fell itself, the woods a mile or so from the relative civilisation that is the Woodlands Centre. This seems at total odds with Harry’s often flustered assertions that he’s a ‘city gent’. I make no comment.

—And it’s the middle of the night; I dunno, maybe one or two a.m.; we’re having a jolly, you know? A walk around the woods. We’ve got the dogs with us and suddenly they start going fucking mad – barking and yapping like they’ve caught a scent.

Sitting looking at Harry, with his good skin, coiffed hair and a forehead permanently scarred with worry lines, I’m not sure I can picture him and his friends, who I can only assume were ‘country types’, walking round a wood in the middle of the night with dogs. The police report states they were also carrying lights – great, powerful lamps – whichlends further credence to the idea that the Ramsays were using the land for hunting. There are several species of deer in Scarclaw woods, not to mention foxes, badgers and other assorted wildlife that the upper class like to kill for pleasure. ‘Lamping’ they call it: catch a deer in a light, makes them freeze.

—Now, like I say, I don’t know what’s going on and I’ve had a few drinks, so I just go along with it, you know? I’ve got no idea where we are and we’re going deeper and deeper into the trees, and the undergrowth is really deep, like right up to our waists – brambles and bracken.

As I’ve said, the Woodlands Centre is surrounded by forest; go just a couple of miles towards the base of the fells and you’re in dense, untamed woodland. Harry’s dogs stop two and a half miles north-west of the centre. This marshy area was fenced off and very dangerous; why Harry and his friends were traversing it in the middle of the night seems more stupid than gutsy.

—It’s really fucking muddy round there, yeah? You can feel your feet getting wet, and before you know it you’re up to your knees in sludge. The dogs are still going mad and there’s this smell … it’s like … well … it’s hard to describe – kind of sweet; meaty; it gets inside you, you know? A stink like that, gets right into your brain, deep; takes a while to let go. I’d like to think we had sort of an idea about what it was. Like, where in the fucking woods do you smell something like that? So we turn the lights on and that’s when we saw it … half buried in the mud. I swear down, I will never forget it as long as I live…

The dogs all shot off into the marsh and began digging, uncovering their find, heaving at it with their teeth, easing bones from sockets, tearing at soft, decomposing flesh and depositing their finds at the feet of their masters. Harry and his friends turned on their lamps, and insteadof dazzling deer, they shone down upon the decapitated and half-rotted corpse of a child. A child whose body had been missing for a year. Fifteen-year-old Tom Jeffries.

—Like I say, I’ll never forget that sight. We honestly thought it was a prank, at first – like one of the guys was messing with us and someone was going to start laughing, and a camcorder was going to appear. But we all just fucking stood there staring. I sometimes see it in my sleep; half buried in the mud, hands bunched into claws like it … like he was a fucking zombie or something, desperate to rise from the grave.

The local police were duly summoned and the crime scene investigators erected their tents. Rather than a national scandal, it was more like relief that the body that had eluded police, investigators, scientists, and even psychics, for the best part of a year, had finally been found.

Tom Jeffries had gone missing on a trip to Scarclaw Fell Woodlands Centre with a group of other teenagers and two supervising adults. Unlike today, when such disappearances run riot on social media, Tom Jeffries’ disappearance was largely ignored by the national press. Of course it was reported, as was the discovery of his body; but the moral outrage that dominates society today was simply absent back in 1996. Maybe it was just the times; there was no such thing as social media in the nineties, and the internet was not the crazed animal it is now.

Or perhaps it was something to do with Jeffries himself. Was it something to do with his personality, his reputation, that simply didn’t warrant a national outpouring of grief? Was it because, at fifteen, Jeffries wasn’t enough of a ‘child’? Was it because he was male, white, and from a stable, middle-class background; an average school student, who blended in, had no real enemies and enjoyed a large group of friends?

Would Tom Jeffries have been remembered more if he had been a little white girl from a privileged background? This is just one of the questions that Six Stories will seek to answer…

In this series, we’ll look at the case of Tom Jeffries from six differentangles. Six people will tell their stories; six people who knew Tom Jeffries in six different ways. When the stories are told, you’ll be able to decide what conclusions, if any, can be drawn from a death shrouded in uncertainty.

Welcome to Six Stories. This is story number one:

—We’ve never had anything like it in Rangers. It was terrible … just a terrible, terrible thing. It drove us apart in the end. No one knew how to cope with what happened up on Scarclaw Fell … and a lot of them just didn’t; didn’t cope, I mean.

It all fell apart. Everything we’d done. It’d been such a huge part of our lives. Such a shame.

This is the voice of Derek Bickers, sixty-two. Derek, along with his friend Sally, were the last adults to use the Scarclaw Fell Woodlands Centre. They had booked it for a loose group of teenagers – their own children and their friends – a group that referred to itself affectionately as ‘Rangers’. That day in August 1996, the group consisted of five teenagers and two adults. One of those teenagers was Tom Jeffries.

—‘Rangers’ – to an outsider, it sounds rather like it was some sort of organisation … which it really wasn’t, was it?

—No, Rangers was never a proper organisation. There were just a few of us at first, just like-minded parents and friends, that sort of thing. We just wanted something for our kids to do; that’s it really. It was never anything more than that. The name came much later; a Lord of the Rings reference I think. And I don’t want to say I was the chief, or the boss, it wasn’t like that really.

What’s that? Oh, when it started? Oh, way back; a few of us were planning a camping trip when the kids were little – three, four years old. We’d set the tents up in the garden and Eva and Charlie were charging round them, in and out, like kids do…

Eva is Derek’s daughter. Eva Bickers was fifteen years old at the time of the trip to Scarclaw in 1996. She was a friend of Tom Jeffries. Charlie is Charlie Armstrong, the son of a friend of the Bickers and of Tom Jeffries. He was also fifteen years old in 1996. He was at Scarclaw too.

—They were grubbing up great handfuls of leaves from the lawn, chucking them at each other; they were covered in mud, twigs in their hair. We were all saying how much they were going to love it – the camping trip, I mean, how they just seemed so at ease in the leaves, the mud, all that. Not like kids today, all phones and iPads. And at least we were trying to get them to connect with the outside…

It probably sounds a bit silly now, all a bit middle-class: a bunch of us old hippy types off in the woods, going back to nature, all that. But it wasn’t; it really wasn’t like that at all. We just had fun. That’s all it was about in the end, just having fun.

I conduct this interview with Derek Bickers on the phone. He’s never heard of me or Six Stories. Sometimes this is just as well. Derek was crucified in the press at the time of the tragedy. He had reporters outside his house, and photographs of him at university – hair over his eyes, acoustic guitar in one hand, the other smoking a joint – were leaked by someone close to him. That betrayal wounded him deeply, more that the headlines that accused him at best of negligence and at worst of pretty much murdering Tom Jeffries himself. It was something that Derek never really recovered from; and, as far as I know, he never found out who had done it.

Again, it all makes you speculate: should a tragedy like the one that befell Tom Jeffries in 1996 happen now, what might be the impact on someone like Derek of the trial by media and the press condemnation that would surely ensue?

Derek Bickers was questioned extensively about Tom Jeffries’ death, but was never charged with his murder. He has spent the years since he was released by the police, keeping his head down, trying to get on with his life. I can only imagine how the weight of such an experience couldwear you down, even if you were a formidable outdoorsman like Derek. It is clear, when he speaks about the past, that he has fond memories of his time in the wilderness with the group. Derek is a former mountain-climber, canoeist, and fell-runner; six foot something with a head so bald it shines, and a neat, grey beard. I ask him whether he continued his relationship with the outdoors after Scarclaw.

—I ran. I’ve always run; but I ran a lot after Scarclaw. Great long routes, cross countries, miles and miles, head down. If something like that ever happens to you, running is the best thing. I’d recommend it to anyone. I used to run until my legs had gone, my knees, my ankles; till I was dead on my bloody feet. It was the only thing that helped … it just kind of ordered it all in my head.

There was speculation that Derek would at least be charged with negligence. Tom and the other teenagers were in his care. Tom Jeffries’ family, however, were adamant they did not want to press charges against Derek, and eventually the lack of evidence and the perseverance of Derek’s friends and family prevailed. The coroner’s report was inconclusive on the issue of foul play and Tom Jeffries’ death was described as ‘accidental’ or ‘by misadventure’. Yet this did not stop the rest of the country, or indeed, the world seeing Derek Bickers as the face of what happened. At least for a while.

—So, in 1996, Rangers were still going strong?

—Yeah. Even though the kids were older. We’d kept it going – the camping trips, the walks, all that.

—There were more members though, right?

—Yeah; well, there were more people who knew about it by then. Our kids had invited their friends from school; the other parents had heard about it and liked the idea. There were a good, maybe, twenty members of Rangers. It was still informal; it was still more or less just walks in the woods, rock-climbing trips, all that, but now we had a name.

—What were the age ranges of the group?

—Well I guess you could say from zero to adult. There were babies, toddlers, pregnant women, teenagers…

—But they didn’t all go on the trips did they?

—Not all of them, no. By then, we’d started a loose weekly meeting in the church hall. It was just a social thing really; people brought cakes, coffee; the younger kids charged about and played and the older ones helped plan the excursions.

—And you say there was no underlying, ideological theme running through the group – not like the Scouts or something?

—That’s correct. It was more about friendship, about acceptance. Just a network of parents and kids; friends of friends; something to do, all that.

—Can you tell me more about the kids who were involved in the trip to Scarclaw?

—There weren’t many of them. That summer in ’96 there was one of those bugs going round the schools; the kids were dropping like flies – vomiting, temperature. It would have been a bloody nightmare out on the fell, we nearly cancelled the whole thing.

By then Rangers was, a bit more organised, I suppose. We had to be: dietary needs, consent forms that sort of thing. These were other people’s kids we were responsible for; we couldn’t muck about. We had a meeting; me and the other adults…

Anyone who helped out with the trips to the countryside did so off their own backs. People gave up their own time to help out with the weekly meetings and the trips. Derek was not by himself on the trip to Scarclaw in 1996; there was another adult present. He maintains that there was no real hierarchy to the group, that the ‘leaders’ were just responsible adults – people who helped out of the goodness of their hearts.

—It was the kids themselves that were determined to go to Scarclaw that summer. I mean really determined. Even if it was only going to be a few of them. They would have been gutted if we’d cancelled. We’d been booking the Woodlands Centre at Scarclaw for years. The kids loved it, knew the place like the backs of their hands. That summer as well, it was beautiful…

Sorry, I’m going on, aren’t I … So, the kids, the people who were there: there were only five kids in the end. Eva, my daughter, was one of them. She was … fifteen. They all were about that age. And then there was me, obviously. And Sally.

Sally Mullen’s son, Keith, was ill at the time of the Scarclaw trip in 1996. Sally, like Derek Bickers, was one of the original members of Rangers and she had agonised for a while about whether she would come and help out on that particular trip. Her husband, however, had taken some leave from work, anticipating that Keith would attend the trip, so he was able to stay at home while Sally went to Scarclaw with Derek and the other kids. This is another ‘what if ’ moment. If Sally had decided to stay at home, would the trip to Scarclaw have gone ahead? I don’t want to speculate on this with Derek, though, there’s no point.

Unlike Derek, Sally Mullen seemed to somehow slip under the press radar. There are several reasons I can think of why that happened. First, she is female. As abhorrent as sexism is, a man is far more likely to be a killer. That’s just how it is. Also, Sally suffers from an intense form of sleep apnoea, meaning that she needs specialist equipment, assisting her breathing while she sleeps. This made her highly unlikely as a suspect. In order to kill Tom Jeffries she would have had to get up in the early hours of the morning, dismantle her sleeping equipment on her own and then re-apply it after she had finished.

—Sally came out of it all smelling pretty clean, didn’t she?

—As she should. She’s as innocent as the rest of us. Look; I took the brunt of it, I know that. I did it to protect not only Sally but the kids as well. They were children, for god’s sake.

Derek was vociferous in his defence of the others and took particular offence at how the teenagers were treated by the police, accusing themof being heavy-handed in their questioning. I believe it was this anti-establishment tone that turned the press against Derek, whereas they left the quiet, compliant Sally Mullen alone.

—Can you tell me a bit about Eva? Your daughter.

—Eva’s a good lass; she was a good baby as well, if that makes sense? Didn’t do much in the way of crying; slept all night. She was just normal; a normal lass. She did well at school – wanted to be a vet.

—Would you say that Eva and her friends were rebels? At the time, I mean.

—Eva’s never been the rebellious type. Well, I say that, but all kids rebel, don’t they? That’s just normal. Sus and I, we always tried to be understanding, easy. ‘Chilled out’ – that’s how Eva’s friends used to describe us. I don’t think we were any more liberal than anyone else, but screaming and shouting never did anyone any good, did it? There wasn’t a lot of conflict in our house. We talked. I think that’s important when you’re raising a girl. You know what kids are like when they get older.

—That’s a good way to raise a child, Derek. No wonder Eva was happy.

—We’re tolerant people; if Eva wanted to dye her hair, wear strange clothes, that sort of thing, we always let her express herself. My thought was always that, if you start telling kids they’re not allowed to do things, the more they’re going to want to do it. Of course we had rules; Eva was fifteen, still a kid. She was a kid when what happened on Scarclaw happened. She was a child.

—You knew the other kids too, didn’t you? You and Sally knew their parents, right?

—That’s right. Most of them had been in Rangers since it began. Charlie Armstrong – he was Eva’s best friend, since they were kids.

Charlie Armstrong is the boy that Derek has already mentioned. The one who had thrown leaves with Eva in the Bickers’ garden. Charlie’s mum was involved with Rangers, but she and Charlie’s father hadbooked a weekend away when Charlie was due to go to Scarclaw. Both of them declined to talk to me.

—Tell me about Charlie.

—Charlie and Eva went to different schools; I think that’s how they kept their friendship going; they saw each other at Rangers and at weekends, without the nonsense you get about boyfriends and girlfriends, and all that stuff in the playground.

I’ve known Charlie’s mum and dad for years; they’re good people; they’ve got a similar attitude to me and Sus: chilled out, go with the flow, that sort of thing.

Charlie was a little more … I dunno … a bit more outgoing, if that’s the right word, than Eva was back then.

In the inquest into Tom Jeffries’ death, this was the debate that nearly saw Derek Bickers and Sally Mullen charged with negligence. As I mentioned previously, it was the parents of Tom Jeffries who were the most vocal in protecting Derek and Sally. As we will discover in further episodes of this podcast, all the teenagers at Scarclaw that night had been drinking alcohol and smoking cannabis. Charlie Armstrong was apparently one of the main instigators or ringleaders in all of that. We’ll get to it in due course.

—You say that Charlie Armstrong was ‘outgoing’.

—I don’t know if outgoing is the right word, though; he was a strong character – that’s probably a better phrase. Charlie was definitely the alpha of the group, the leader of the pack. He smoked cigarettes; and his mum and dad knew he did. He was into his music … death metal or something like that … not that that has anything to do with anything. He had the long coat, the long hair, T-shirt with bloody devils on it, or some such; all that. I think he was excluded from his school a few times.

This is another point of interest and something that was raised atthe inquest. Charlie Armstrong was thought of as the leader of the older teenagers. His appearance and music preferences were raised more than once in the press, to the derision of the parents, as well as Charlie’s peers. Remember, this was before Columbine and the ‘trench-coat mafia’ hype in the US. Marilyn Manson was still relatively unheard of in the UK.

It is true, however, that Charlie Armstrong was excluded from his school a number of times. I managed to track down ex-deputy headmaster Jon Lomax to get his take on it. Mr Lomax is an old man now, but his mind is still sharp and he reminisces about his school life with an unbound delight, his answers to my questions punctuated with laughter. Our phone conversation is brief.

—Mr Lomax, you remember an ex-pupil of yours called Charlie Armstrong?

—It’s funny you should ask, actually, because, even with the attention he got after what happened up at Scarclaw, I would still have remembered him.

—What do you remember?

—He was a true rebel. Or a pain in the arse, whatever you like! He was forever stood outside my office.

—Really, what for?

—Oh, just little acts of defiance; nothing that important in the grand scheme of things. He wouldn’t tie up his tie properly – had it knotted halfway down his front or not on at all; holes in his blazer; smoking; that sort of thing.

—You must have overseen hundreds of thousands of children in your time; it’s funny how Charlie stuck with you.

—I suppose so, but you do remember the ones like Charlie, more than you do the ones who behaved… What I remember most about Charlie, was just how smart he was. He was a lazy underachiever; it used to drive his teachers potty! You know the sort, forever getting ‘could be very good if he applied himself ’ on his report. Underneath it all, though, there was no harm to him. He wasn’t a nasty child, and, believe me, I have encountered perfectly nasty children – nine times out of ten with perfectly nasty parents!

—He was excluded wasn’t he?

—Yes. Maybe more than once, I don’t recall. But the first time does stick in my memory; mostly because of how his mother behaved about it.

It was a lot of silliness really, but the point is, schools need to have standards. It’s different these days, I know, but Charlie and his mother both knew fine well what we allowed and what we didn’t.

—What did he do?