7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

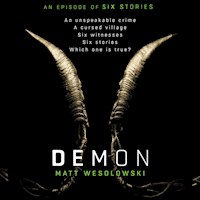

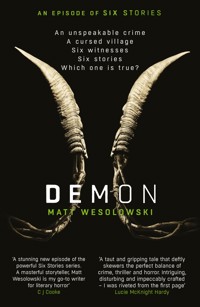

Scott King investigates allegations of demon possession in a rural Yorkshire village, where a 12-year-old boy was murdered by two young children. Book six in the spine-tingling, award-winning Six Stories series. 'Matt's books are fantastic' Ian Rankin 'An exceptional storyteller' Andrew Michael Hurley 'Matt Wesolowski is taking the crime novel to places it's never been before' Joseph Knox, author of True Crime Story 'A stunning new episode of the powerful Six Stories series. A masterful storyteller, Matt Wesolowski is my go-to writer for literary horror' C J Cooke, author of The Lighthouse Witches ______________ In 1995, the picture-perfect village of Ussalthwaite was the site of one of the most heinous crimes imaginable, in a case that shocked the world. Twelve-year-old Sidney Parsons was murdered by two boys his own age. No reason was ever given for this terrible crime, and the 'Demonic Duo' who killed him were imprisoned until their release in 2002, when they were given new identities and lifetime anonymity. Elusive online journalist Scott King investigates the lead-up and aftermath of the killing, uncovering dark stories of demonic possession, and encountering a village torn apart by this unspeakable act. And, as episodes of his Six Stories podcast begin to air, and King himself becomes a target of media scrutiny and public outrage, it becomes clear that whatever drove those two boys to kill is still there, lurking, and the campaign of horror has just begun... ____________ 'Matt Wesolowski is boldly carving his own uniquely dark niche in fiction' Benjamin Myers 'Matt's real skill is in finding a deeply human story and twisting it with the paranormal, touching the reader and scaring the wits out of them' Chris MacDonald 'One of the most exciting and original voices in crime fiction' Alex North 'A wonderful writer' Chris Whitaker 'I'll be rereading these books forever' Sublime Horror 'The master of horror, of mixing folklore with urban myth and real life. Terrifyingly good' Louise Beech 'A taut and gripping tale that deftly skewers the perfect balance of crime, thriller and horror. Intriguing, disturbing and impeccably crafted – I was riveted from the first page' Lucie McKnight Hardy, author of Dead Relatives Praise for the Six Stories series: **Longlisted for Theakston's Old Peculier Crime Novel of the Year** **Winner of the Capital Crime Best Independent Voice Award** 'A captivating, genre-defying book with hypnotic storytelling' Rosamund Lupton 'Original, inventive and dazzlingly clever' Fiona Cummins 'Daisy Jones and the Six gone to the dark side. I couldn't put it down' Harriet Tyce 'Bold, clever and genuinely chilling with a terrific twist' Sunday Mirror 'Insidiously terrifying, with possibly the creepiest woods since The Blair Witch Project' C J Tudor 'Frighteningly wonderful … one of the best books I've read in years' Khurrum Rahman 'Disturbing, compelling and atmospheric, it will terrify and enthral you in equal measure' M W Craven 'A dark, twisting rabbit hole of a novel. You won't be able to put it down' Francine Toon 'First-class plotting' S Magazine 'A dazzling fictional mystery' Foreword Reviews 'Readers of Kathleen Barber's Are You Sleeping and fans of Ruth Ware will enjoy this slim but compelling novel' Booklist For fans of Serial, The Conjuring, C J Tudor, Fiona Cummins, Sarah Pinborough and Catriona Ward

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 419

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

In 1995, the picture-perfect village of Ussalthwaite was the site of one of the most heinous crimes imaginable, in a case that shocked the world.

Twelve-year-old Sidney Parsons was savagely murdered by two boys his own age. No reason was ever given for this terrible crime, and the ‘Demonic Duo’ who killed him were imprisoned until their release in 2002, when they were given new identities and lifetime anonymity.

Elusive online journalist Scott King investigates the lead-up and aftermath of the killing, uncovering dark stories of demonic possession, and encountering a village torn apart by this unspeakable act.

And, as episodes of his Six Stories podcast begin to air, and King himself becomes a target of media scrutiny and the public’s ire, it becomes clear that whatever drove those two boys to kill is still there, lurking, and the campaign of horror has just begun…

Demon

MATT WESOLOWSKI

‘This glen was in very ill repute, and was never traversed, even at noonday, without apprehension. Its wild and savage aspect, its horrent precipices, its shaggy woods, its strangely-shaped rocks and tenebrous depths, where every imperfectly-seen object appeared doubly frightful – all combined to invest it with mystery and terror.

No one willingly lingered here, but hurried on, afraid of the sound of his own footsteps. No one dared to gaze at the rocks, lest he should see some hideous hobgoblin peering out of their fissures.’

—William Harrison Ainsworth

The Lancashire Witches

‘They had engaged in mortal combat with one another, they had cooked strange ingredients over a smoking and reluctant flame with a fine disregard of culinary conventions, they had tracked each other over the countryside with gait and complexions intended to represent those of the aborigines of South America, they had even turned their attention to kidnapping (without any striking success), and these occupations had palled.’

—Richmal Crompton, Just William

Contents

Please be aware before you proceed that this book contains fictional violence against children and animals that may cause some readers distress or upset.

—Matt Wesolowski

Dear Mum,

You would have hated it today. You would have bent down and whispered in my ear, ‘Look at the fucking state of that.’ I loved it when you used swear words, Mum. You only ever whispered them. Sometimes I whisper them too. I do it in bed, when Dad’s clattering round downstairs or outside having a smoke.

I whisper them and sometimes I cry. But not that much and definitely not when Dad’s there.

It was the village fete today, and it looked properly empty without your stall there. There was all this bunting everywhere with Union Jacks on it. That was new.

It looked shit, Mum, haha!

Everyone stared at me when I walked in, like I had two heads or something. I thought, Look at the fucking state of that, in your voice, and I swear I felt your hand on my shoulder, I smelled your hair, felt it tickle. Heard all the beads in it jangle.

I could almost smell the incense that you used to light and put on your stall. Loads of people bought it as well, Mum, I remember that. I saw one of those little brass Buddhas you used to sell on Nelly Thrunton’s windowsill the other day, so there. To be honest it was really weird – the first fete without you. They had one of those pig roast things where your stall used to be; a whole pig on a spit over this grill thing, and you could see its face and everything. You would have been properly annoyed. I held my breath when I walked past it, just like you would have done.

There wasn’t any of those goldfish in bags as prizes on the whack-the-witch stall, you’ll be pleased to know. I was worried that they’d bring that back, but they must have listened to you for once. There was loads of little kids lined up to have a go. I don’t know why they all go so mad for it – it’s proper lame: the stick is foam, the witch isn’t even scary and if you miss her, Mr Diamond gives you a bag of sweets anyway. What’s the point?

Mrs Bellingham had her jam stall, and all the old biddies were fussing on about it. She had this mad new flavour – gooseberry and lychee, or something, and all these little samples on bits of toast, like in the supermarket. But I didn’t have one.

I’ve still never heard anyone my age say ‘old biddy’ either, Mum; that was totally one of your old-person things. When I walked past, they all turned to look at me with their sad eyes, like sheep. None of them said anything though, none of them asked if I was OK or was I having a good day or anything like that either. I heard them all whisper as well – pss-pss behind my back.

I remember when you got mad once and said that it was full of snakes round here. Now I think I get what you meant. But I think they’re more like sheep: old and white and fluffy and boring. Don’t tell Dad I said that.

Mr and Mrs Hartley were wandering round like they were the bosses of the fete, as usual, and everyone was shaking their hands and saying how lovely it was, and I wanted to say it was fucking shit. Imagine, Mum, if I’d gone up to them and said that. There was nothing to do, really, just boring stalls and food. I wanted to buy a cake, and I joined the queue, but then everyone said I should go to the front and it was proper embarrassing, so I just left because I couldn’t be bothered with them all looking at me and saying they were sorry and all of that. I did go to the book stall, because Mr Womble (remember how you used to call him that?) was the only one who didn’t look at me with stupid sheep eyes. He was too busy with his pipe, and his face was all red, and he was wearing this massive jumper, and he smelled of burned paper. His hair still grows out of his ears and nose too, in those great big clumps. I bought a new Just William, which he said I could have for 5p because the cover was all hanging off. It was William the Fourth, which I’ve not got yet.

I just went home after that.

Dad sent me out after tea to ‘play with my mates’ because he had stuff to do, but he didn’t know I had William the Fourth in my back pocket, so I went to the secret place to read it. I saw the new lad on the way. He was walking over from Stothard’s rec, where they all play football. I bet he’s just like all the rest of them round here, a right wazzock.

No one saw where I went. I was smart: went one way then doubled back on myself up through the dip in the top field and along the ditch. No one was there, they were all playing football. It was peaceful. It’s always peaceful there, Mum, and I sat in the shade and read Just William, and I cried a bit, Mum, but only a little bit, and only because I remembered when you used to read Just William to me. When I read it, I heard it in your voice.

I’m going to start taking a cushion with me, but what if someone stops me and says, What are you doing? I’ll say, I’m taking my cushion for a walk, thank you very much! That’s the sort of thing you would say, and you would laugh and you would have said, That showed the old fuddy-duddies.

Remember when you told me Richmal Crompton was actually a woman, and I didn’t believe you? I didn’t think a lady could write stories like Just William, and you said no one else did either, and no one would have read it back then if she hadn’t changed her name to sound like a man. You told me I need to always look out for that sort of unfairness in the world, because it’s still here, you said, it’s still everywhere.

I waited until I had stopped crying before I went home, but it was dark by then and I was worried that Dad would go mad, but he was snoring on the sofa when I got in, so I read just one more William story, and I remembered that time we made liquorish water and I pretended to like it, and Dad said, ‘What’s this pond water doing in the fridge?’, and we couldn’t stop laughing.

I thought I’d write this just before I go to sleep. School tomorrow, worse luck.

Goodnight, Mum. Xx

http://www.missingpersonsteam.uk

Ussalthwaite

England

North Yorks. Police

[View sensitive images]

Gender: Male

Age Range: 30-50

Ethnicity: White European

Height: 175cm (5 ft 8 ins)

Build: Medium

Body or remains: Body

Circumstances: Deceased male found within cave area of Ussal Bank Kilns, Ussalthwaite

Hair: Brown

Facial hair: Beard

Distinguishing features:

Tattoo – unspecified – left arm – image: ‘Celtic cross’

Tattoo – unspecified – left forearm – image – ‘unspecified tribal design’

Possessions: None.

The Demonic Duo Have Served Their Time in Hell

Leonora Nelson

The men who were once children have served their time. Now has the idea of revenge replaced a need for justice?

A caveat before I even start, before I’m accused of being a hand-wringing Marxist or some kind of war-crime sympathiser: the crime perpetrated by two twelve-year-old boys in Ussalthwaite, North Yorkshire in 1995 was abominable. Some might say unforgivable.

The idea that one or both of the ‘demonic duo’, now men in their thirties, will be named leaves a nasty taste. If doing so is not a dog-whistle to provoke some kind of vigilante justice, then what is it? What is the purpose of exposing people who have served their allotted time and have been judged to be successfully rehabilitated into society?

The ‘demonic duo’ have rightly paid for what they did; they are figuratively and literally not the people they used to be, but that may never be enough.

The word flittering though social media is that a member of the public has discovered the identity of one, if not both killers, and is prepared to reveal them for the highest price.

Whoever’s going to do this needs to take a long, hard look at themselves and decide who the demon really is.

Episode 1: The Bad Place

—There was only one remotely bad part of Ussalthwaite, and it wasn’t exactly bad. It’s like anything really, there’s a rotten apple in every batch. .

It’s just outside the village. You have to go over Ussal Top, a big steep hill covered in heather, to find it. Not really Ussalthwaite village I suppose. Well, that’s where they found him the other week, that man.

Have they found out who he is yet?

Dear me, his poor family.

When I was a girl, most of us were happy just messing about on the hill or wandering down to Barrett’s Pond. It’s lovely down that way; there’s a meadow and bluebells on the banks in spring. That’s where we went when there were too many older ones on Ussal Top. There were reeds and you could find frogs or catch sticklebacks in jam jars. We’d take sandwiches and scones that our mams had made. It seems mad now, doesn’t it? Can you imagine parents letting their little ones wander round a pond trying to catch fish with jam jars these days? It would never happen.

Nowadays, they’re just sat inside on their phones, aren’t they?

Back then though, our mams and dads told us to get out the house and be back when it got dark. It was that safe around here. We had all we needed, the sun and the fields and each other. Paradise on earth. That’s Ussalthwaite alright. That’s the real Ussalthwaite.

We weren’t daft, neither was our parents. If I wasn’t home at or before 5.30pm on a Saturday or if they even thought I’d been to the kilns, I was grounded for a month and probably got a whack on the arse with a slipper too. Of course, everyone always went and played at the kilns on Ussal Top. The one place you weren’t allowed to go. The bad place.

That’s kids for you. That’s about as naughty as it got in Ussalthwaite when I was a girl.

Things are very different now.

Welcome to Six Stories.

I’m Scott King.

The voice you’ve just heard is that of long-term resident of the North Yorkshire village of Ussalthwaite, Penny Myers. Penny says she has not and will never live anywhere else.

Ussalthwaite is the epitome of ‘God’s own country’, although, considering what happened there in the seventies and again in 1995, the terms seems ironic.

Now it has seen a suicide. A man, still unidentified. This series, however, is not about him. Not yet. But it was the discovery of his body that brought me here, to this small, picturesque village nestled in the stunning Yorkshire countryside. But this suicide is sadly not the first time tragedy has struck here.

Before we travel to this beautiful village in the middle of nowhere, let me say a few words about what we do here at Six Stories.

We look back at a crime.

We rake over old graves.

I’d just like you all to know that I’m no expert, I have no degrees or PhDs in criminology or psychology. I’m not trying to change laws or challenge beliefs. This podcast is like a discussion group at an old crime scene.

Six perspectives on a crime; one event through six pairs of eyes.

In this series, we’re going to talk to six people who were there at the time of a terrible tragedy; a tragedy that, despite the weight of what occurred, was very swiftly forgotten. It’s inexplicably difficult, even today to find much on the subject of the strange events of more than twenty years ago that sent shock waves through this peaceful, rural Yorkshire community.

Sometimes, looking at the past can have consequences for the present. Sometimes our raking disturbs a plot and sometimes people don’t like old graves disturbed. I can understand that. Some graves should be left well alone. Sometimes we don’t need to pull to pieces things that are better left to rest.

Like, perhaps, this one.

It was here in Ussalthwaite, on a bright morning in September, 1995, halfway along a secluded bridleway, under the shade of some trees, that a local man walking his dog saw what he thought was rubbish bags that had been tossed into a small stream. It took a few moments for the man to realise exactly what he was looking at.

Twelve-year-old Sidney Parsons had endured a severe beating; he suffered broken ribs, cuts and internal bleeding, and his small body had been laid, face down, in running water. A rock was embedded in the back of his skull, it had been thrown with so much force.

I don’t derive any pleasure from giving such gruesome details about the fate of Sidney Parsons, but I think it’s necessary that you know how violent the attack was on a boy who’d simply been sent to the shop by his mother and never returned.

—It’s never been the same round here since then. I would have said that Ussalthwaite was the perfect village. I really would. Then this happened, and no one’ll ever forget it. Not as long as they live.

Ussalthwaite, nestled in the heart of the North Yorkshire Moors National Park, is stunning. It’s a bit of a time warp – cottages nestled along cobbled streets. Walking around, you can almost hear the strains of Dvořák’s Symphony No. 9 on the coal-smoke tinted breeze. Flowers tumble from every window box and spoiled cats loll on windowsills.

The moors themselves were formed in the Ice Age; uplands, lowlands, moors, coasts and cliffs.

Bronze Age and Roman remains have been found across the wider area of the National Park. There are decommissioned nuclear fallout shelters from the cold war era, too. Nature swallows the past swiftly here.

A few remote sheep farms dot these wild uplands, and rivers gurgle through patches of woodland. Time passes here with the flowering of the heather – the cry of the curlew and the golden plover marking the slow turn of the seasons.

But not 150 years ago, this vast landscape of hills and heather hummed with industry. The steam of rail-building met the black smog of the mines; furnaces roared and steam power shunted ore and coal further north and to the coast.

The village of Ussalthwaite itself had a brief flirtation with ironstone mining in the mid-1800s, before the rock went dry. The industry finally left in the 1920s. Just a spatter of the mining cottages remain.

There are remnants scattered in and around Ussalthwaite from its industrial past; the shadows of trams and railways wind past ruined chimneys and monolithic slag piles. Hay meadows now encroach on the remains of pump houses, and the metal grates that seal the ancient pits are grown over.

This land is good at forgetting.

Its people? They wish they were.

—I’m good at this whole Zoom chat rigmarole, you know. You have to be, don’t you? We’re not immune to Covid, even all the way out here. I set up the Ussalthwaite WI Zoom meetings to keep our spirits up. There’s a few of the older ones who are house-bound or frail, and it’s a lifeline for them. It brought light here during that dark. If we hadn’t embraced technology, it would have been the end for a lot of us. Mind over matter, isn’t it? We might be falling apart out here, but our brains are tough as old boots.

I talk to Penny Myers via Zoom. She sits in a comfortable-looking armchair. Like most of Ussalthwaite’s residents, Penny is well off, and her home is neat, polished and cosy. She’s less and less able to move about much these days, but she can still run online bingo like a pro.

Her carer wanders past in the background occasionally. He’s keeping an ear out to hear what I’m asking; he’s making sure Penny doesn’t upset herself.

I somehow doubt that’s going to happen, but it’s early days.

—I sometimes wonder: if our parents hadn’t been so adamant about us not going up to the kilns, then maybe we would never have passed that down to our kids, and none of it would have happened? I dunno. You can’t stop badness; you can’t stop the devil being the devil, can you?

There are many different stories surrounding Ussalthwaite and what happened there in 1995. I guess I’m here to pick out which one, from six, is true. So where do we begin? Let me tell you a little about the kilns. In fact, no, I want to give Penny that honour. She lived through the horror.

—Well, you can see ’em online, of course. The kilns on Ussal Bank. People usually catch them proper nice, with the sun shining on them or else the sky all purple behind them, but when you’re up close, they’re not all that picturesque, I’m telling you now.

There’s a stretch of cliffs about a mile as the crow flies from Ussalthwaite village, over the hill and onto Ussal Bank. This was the main site of the mine, back when the ironstone stood out from the cliff face itself. The kilns are less like an oven, more like a sort of viaduct shape – a line of great stone arches built into the side of the cliffs. They’re ominous; a row of ten black tunnels, about twelve feet high, earth and slag tumbling from their entrances. Frozen in time. Crumbling, grey brick.

—Me granddad worked in the kilns: he used to burn the ore in the furnaces, to get it ready to be sent up to Durham to be smelted. Some nights, when there was a storm, he used to take me dad and his brothers up onto the moor to watch the lightning hit the cliffside. He used to tell them it was as black as the gates of hell in there. He said he was lucky he never had to go into the mine itself. He said a devil lived down there, under the hills. There were a load more people in the village when me granddad was a lad; more houses as well. Most of them, he said, worked in the mines. They had some funny old stories, I can tell you that for nowt.

—What kind of stories?

—I think he was just trying to scare us kids, you know? Part of a grandparent’s job isn’t it, to tell tall tales? One story he always used to tell was about poor old Pat Wood, who lived down Pitt Cottages. Poor fella. Blind as a bat from the mine. Probably had early dementia as well, God rest his soul. Me granddad used to say that there was a story in the pubs that Pat Wood was one of them what saw something in the mine. You see, by the 1920s, it was getting harder and harder to get hold of that ironstone, and they had to dig further and further into the hill. The companies were laying off more and more lads, because there was no more work as all of it was gone. Pat Wood, me granddad said, was on the final shift down there when there was an incident.

—What sort of incident?

—Stink damp. It’s gas what can build up inside mines. Toxic it is, even a little bit of it. They dunno how long it was poisoning them down there, in the deepest part of the mine, but they told their gaffers there was a smell. Rotten eggs. Hydrogen sulphide. They should have got them out of there right away. They should have known, but no one listened. No one believed them, thought someone was playing practical jokes. Pat Wood was the only one what lived. The rest of the poor buggers died within a few weeks; bronchitis. It was a tragedy. After that there was a strike. The company went bust and they filled in the mine. Good riddance.

—You said that Mr Wood saw something.

—That’s what me granddad used to say. That was the tale they passed round in the pub. I daresay it was a story soaked in too much ale and not enough work, but it used to scare me as a kid. And me dad used to tell me he saw Pat Wood out and about, every so often, when he was little. Used to scare him something rotten, staggering around and shouting about summat from a long time ago buried down there. Pat said he seen a terrible, long shadow when there were no men to cast one, heard summat laughing under all that rock. Poor bugger.

—It sounds like a combination of dementia and the long-term effects of the gas, perhaps?

—Aye, it does, doesn’t it? Me granddad used to tell us the old tale to keep us in check. He said that those miners had been poking their noses in places they shouldn’t have been down there in the dark. He said if we did the same we’d end up like them. He said there’s things down there that no kiddie should be asking about, and that’s as far as he would go.

—What do you think now?

—It’s not a very nice story, is it? I guess that’s why we were told to stay away from the kilns and all. I think there was a bad feeling about the whole place. It’s what happens when there’s tragedy, isn’t it? Stories begin, rumours start, shadows get longer.

The shadows of Ussalthwaite and the kilns are especially long. The next tragedy surrounding the place is just as speculative as that of Pat Wood.

—There was some young girl who came here on her holidays back in the seventies. What was her name – Julie? Something like that. Well, she ended up in one of those … what do you call them these days? Not an asylum, but you know what I mean, don’t you? They reckon she’d been poking around in them kilns when she was here, messing with things better left alone.

It’s a story I’ve heard, but one we need to leave aside for now.

As early as the late 1980s, Ussalthwaite became a sought-after place: the affluent bought holiday cottages and second homes here. Refurbishments began on many of the old mining houses and barns. Wood-fired hot tubs and decking began to replace allotments and blackberry bushes. Then a wave of new families moved into the village, bringing with them prosperity. The old farmland was bought up and developed, barns were converted and new ones sprung up across the barren moorland.

—You can build what you like here, paint it all over, but I’m telling you now, them kilns are a bad place. That’s where they waited for him, those two. They waited for young Sidney Parsons up at them kilns, and that’s where they battered him; then they dumped his poor little body in the stream to die, like he was nowt more than rubbish.

The kilns are still there today, crumbling and silent. There’s no heritage trail or public information boards; no neat fences politely holding back the public, like at similar, more tourist-friendly sites, such as Rosedale.

The beauty of the area can swiftly turn ominous – with a rainstorm or fog. And at night, when the wind howls across the barren hills of heather, the stories of a devil living beneath Ussal Bank suddenly don’t seem so farfetched. As we’ll come to discover in this series, there are many more stories about the kilns, stories hidden in the shadows of their vast silence. Stories older and deeper than the deadly stink damp lurking beneath the hills.

—So you see, we’ve had horrors stories, here in Ussalthwaite. But in ninety-five we got a new one. Those two boys and what they done to Sidney Parsons. And I think it’s scarier than any of those old stories my grandad told us.

We take some time to have a tea break. Penny’s carer pops up in front of the camera and tells me he’s going to turn off her video and audio for a few minutes; give her some time to refresh herself. That’s understandable; we’ve painted a picture of a place and now we need to delve down into it.

The event that made the name Ussalthwaite infamous occurred in September 1995. The savage murder of a young boy. By two children.

A horror. There’s no other word for it. Horror upon horror. But we need to find a place to start, which is why I want to begin with Penny.

—I think it’ll be good to just get it over with.

—OK, thank you, Penny. Now, when did it all start, for you?

—It all started at the kilns. They’re spooky; even on a sunny day, those kilns were dark and damp. But they weren’t deep; just ten feet or so into the hill. We dared each other to go right to the back, where it got darkest and you could feel all that ancient rock pressing you in. It was dangerous; and it’s only by the grace of God that no one got hurt worse than a black eye or a scraped knee.

There was loads of stuff from the kilns – bits of smelt and iron ore all over the place that we picked up. You had to hide it from your mam and dad, mind, cos that would be evidence you’d been up there. There was other stuff too, all the waste – rock and crystal from deep underground. People found even older stuff too – arrowheads and that from the Bronze Age.

Slag heaps from the iron mines in the area render all sorts of treasure at sites like these. It isn’t unusual to find Roman and Bronze Age artefacts; bits of pottery and weapons, blackened by age, dug up from the mine and discarded in vast heaps of earth.

—We all wanted them for show-and-tell at school; or we played with them.

—Are there many of you left – the families from back then?

—Not many from when I was a girl, no. Most people upped and left after what happened here in ninety-five. All these along my street are holiday houses these days. There’s one or two of the old ’uns like me what are still here.

—I’ve been past and seen the Hartley house. No one’s bought that one, have they?

—No one ever will either. It needs knocking down, demolishing; its bricks ground and scattered on the moor. Folk still avoid walking past there. Even today. I still feel sorry for them two. Ken and Jennifer. All they ever did was good, and look what happened to them.

Penny’s correct; people do avoid the Hartley house. I sat in my car yesterday, parked up on the tiny, single-lane road that winds through Ussalthwaite. Pretty little terraced cottages sit on banks on one side; a stone bridge leads over the green rush of the River Fent to a wooden-walled community centre with green, anti-climb fences around the edge of a 4G football pitch. A crumbling church with restored stained-glass windows sits atop a squat hill surrounded by ancient tombstones wreathed in ivy. I saw no cars drive past, and the passers-by made a point of crossing the road when they came to that particular house, the former home of Ken and Jennifer Hartley. It’s at the very end of the row, and sits in the shadow of a sprawling plum tree in its front garden; the branches look like dense, black fists covered in knobbly wooden claws. The windows of the house are boarded up, and there’s a metal grate on the front door. The front garden is a mass of rotted fruit and dead leaves. It’s a huge contrast to the affluence of the rest of the village.

—I’d say the Hartleys were the first well-off folk what moved here. They were professionals, both of them, educated. Lovely couple. They gave Ussalthwaite its heart back, them two. Always planting flowers and litter-picking – getting the local kids involved, too.

—How many children did the Hartleys have?

—None of their own. I think there was a problem there, but you don’t ask, do you? It’s not good manners.

At least before the event of 1995, what’s been reported about Ken and Jennifer Hartley is nothing but complimentary. By all accounts, the pair were good-hearted pillars of the community. It was the Hartleys who started up a Neighbourhood Watch scheme and encouraged other residents to report crime. They lobbied for funding for local transport and a new community hub. Penny tells me that Ken and Jennifer Hartley brought a genuine sense of pride back to Ussalthwaite.

—They brought back some of the old ways, them two. That’s why folk took to ’em so easy, see? We started up the harvest festival again, and I tell you what, that was lovely.

—I have listeners from overseas who might not know what a harvest festival is. Can you paint a picture of what it was like?

—Oh it’s a very English thing, isn’t it? When the heather across the moor turned purple you knew it was nearly harvest time. When I was a girl it was a big event, the harvest festival; all us kids dressed up as pumpkins and onions. Folk showed off their cabbages and parsnips and whatnot that they grew on their allotments. They used to have animals on show as well; the sheep and the cows and that. Cider and a band. Country dancing. When I was a girl, we had Morris men swinging their hankies and jangling their bells. It was lovely. But times move on, don’t they? No one had nowt to show, and the harvest festival just faded away. When Ken and Jennifer brought it back, it were new. More charity-based, with everyone bringing tins of food for the old folks and the infirm. We’ve been collecting for the food banks these last few years.

—It sounds like the festival brought everyone together back in the nineties.

—It really did. We were a community again. They started it off, the Hartleys. Good people.

We’re going to stay in the nineties. By the time the Hartleys had brought the harvest festival back and were renovating their house, Penny was in her forties, with her own children. Her husband played in the Ussalthwaite brass band, something else that had been set up by, you guessed it, Ken Hartley.

—Can we talk about the…

—Those boys? Aye. I know. I’ve been dancing, haven’t I?

—Actually, no. You’ve painted a solid picture of Ussalthwaite back in 1995. It’s what we need – some context.

—The thing is, this story is just horrible, it’s sad; you know those crime stories where there’s a detective with a drink problem and it all gets tied up at the end? Well that’s not this story, it’s not what happened here in ninety-five. So I’m sorry if I go on a bit, because it were terrible, and I’m going to tell it like it is. Like it was, I suppose. But it’s not going to have a nice bow on it at the end, I hope you know that?

—I know.

There’s a long pause before Penny goes on. Her fingers grip the arm rests of her chair, her eyes gazing past the camera of her laptop, through her front window, I presume, over the empty street and into the horizon where spring sunlight dapples a Yorkshire sky. I wonder what memories are coming back, what this digging will unearth. I feel like those miners going deeper and deeper for the iron ore. How deep is too deep? I wonder. What good is there in opening this old wound? Taking an old woman back to a place of trauma?

—It all began with that one what came to live with the Hartleys. Robbie, he was called. Robbie Hooper. No one knows what he’s called now, do they? The other one, Danny, he was from here. An Ussalthwaite lad, born and bred. He lived up top – over the bridge. His dad were a farmer. Sheep. He was from one of the old Ussalthwaite families. Richard Greenwell. Quiet man. Spoke only when he needed to. They had a dog, Jip – lovely old thing with odd eyes. Danny went to school with our Elsie – that’s my daughter. As far as I know he were nowt to talk about really. Just a quiet farm lad. Didn’t really have much to do with no one else. Got the bus with all the other kids up to the school. But then his poor mother died, God rest her soul. I don’t think he ever got over that.

The death of Saffron Greenwell, Danny’s mother, and particularly the way she died, rocked the close-knit village.

—I’m not one to speak ill of the dead, but she was a funny one, Saffron Greenwell; one of them sixties flower children, she was. She did massage and that, yoga and – what was it? – some kind of healing, I daresay. Whatever that is. Summat to do with your auras and whatever. She made a living from it. Right popular with tourists. She travelled all over to see her clients, you know. She was back and forth, all the way to Harrogate sometimes.

Saffron Greenwell was a self-employed yoga teacher and therapist; she also practised reiki and crystal healing. Her list of clients in the North Yorkshire area was extensive, and she was considered, in alternative-therapy circles, to be one of the best.

—Well I’m not one to say what she was doing but Sally Bentley, who lives on Bramwell Court, says she was up on the top floor one night, rocking her Anthony to sleep, and she looked out the window and saw Saffron Greenwell and someone else, she couldn’t make out who it was, walking down from Ussal Top. Saffron, she says, was naked as the day she was born! One o’clock in the morning and all.

I never knew how she and Richard got together. Chalk and cheese they were. And after that, I don’t know why he even kept her. Maybe it was for the boy? Who can say? She wasn’t exactly a good example for him. Lighting fires all over the land, telling folk she had a right to do what she liked. No wonder their Danny turned out the way he did. No wonder he done what he did.

It was in December 1994, the day after Boxing Day, that Danny Greenwell, then ten years old, found his mother hanging from an electrical cord in one of the barns. As far as I’m aware there was no note. Her death was ruled as suicide. There were no suspicious circumstances.

—She were the one who kept everything going on the farm. Danny’s dad, Richard, was a sheep man, like his dad and his dad’s dad. All he knew was the fields and the flock, so when she died, he suddenly had a young lad to care for too. Poor thing. We tried to help, all of us, made him food and that, but they didn’t want to know. Kept themselves to themselves. Threw it all back in our faces.

But what happened with Sidney was nowt to do with what happened to Danny’s poor mother. He only turned when that Robbie arrived. It was Robbie what changed him, I swear on me old mother’s grave.

Robbie Hooper arrived in Ussalthwaite in February 1995. He was the same age as Danny Greenwell and Sidney Parsons: twelve.

—There was summat different about the lad. Ken and Jennifer Hartley told anyone what would listen that Robbie was coming to live in Ussalthwaite for six months. They thought that being out here in the middle of nowhere, out in the sticks, in a small community, would be good for him. They never said that much about him before he arrived though. I think there was summat going on behind the scenes with him, you know?

From what I have managed to piece together, Robbie Hooper was the child of a family friend of the Hartleys. The Hoopers lived far away from Ussalthwaite, in Gloucester, and had suffered their own terrible tragedy. Robbie’s parents Mildred and Sonny were involved in a car accident. Mildred sadly died, and Sonny lay in critical condition in hospital. Robbie, their only child, had nowhere to go, so through some kind of arrangement ended up staying with the Hartleys. I want to stay with Robbie’s arrival in Ussalthwaite, two hundred miles north.

—Now don’t get me wrong, that man and his wife, they were saints, taking in the boy like that. They had patient hearts, the pair of them. I remember Ken saying to us that children need patience and kindness in order to thrive. He told us that Robbie would need a little more from all of us, from the community – he needed kindness, understanding.

—Were the people of Ussalthwaite obliging?

—Oh yes, of course we were. Everyone respected the Hartleys. They were grateful to us. Not like Richard Greenwell, who shut the door in our faces when we tried to help.

Penny’s not sure when exactly Robbie Hooper arrived but his presence came without fanfare. One day he was in Ussalthwaite.

—I remember our Elsie pointing at him from her bedroom window. Hers was up at the front, looked out over the street, and I was putting away clean washing when she says, ‘There he is, Mam.’

I don’t know what I was expecting, really. He was a bit funny-looking I suppose, all hunched and hulking with a big forehead. He was walking past our place wearing a rucksack and he must have sensed us watching, because he looked up at us and smiled.

I know what you’re waiting for – there was something in them eyes; that gaze chilled me right to my bones? Well there was none of that. He glanced up, saw me stood at the window with a load of washing, and all that was wrong with him was some gaps in his teeth. Then he just kept going, went about his business. I have to say, it was an anticlimax.

—How do you mean?

—Well, there was this great, big build up wasn’t there? The Hartleys telling us all how we had to be kind and that; all this mystery about why he’s even come here in the first place. I was a little disappointed if I’m honest. Not a lot goes on round here, you see, so young Robbie was the talk of the village. I asked a few other mams who had kids at St Catherine’s what he’d been like in school, and they all said he was quiet, ‘just keeps hisself to hisself’. I swear that’s all I ever heard from anyone about this Robbie. I think no one really knew what to do. He wasn’t one of our own – none of us really knew what we were supposed to do for the lad. We couldn’t go round bringing soup and stuff, could we?

Penny says that no one really saw much of Robbie at first, save for when he walked to the bus stop or back up the road to the Hartleys’ house at the end of the street.

—I feel like maybe we all could have been a bit kinder; gone out of our way to talk to him, made him feel welcome, you know? I think everyone was waiting for someone else to do it. It would have seemed odd though, wouldn’t it? All these adults talking to a young lad like that.

—What about the children in the village? Did they have anything to report about Robbie?

—I asked our Elsie, and, well, she was at that age where she was getting awkward, self-conscious, all that, and she wasn’t going to walk up to some strange new boy she didn’t know and make friends, was she? Maybe when she was little, but not then. No, she didn’t see much of him. Even on the bus and in school, he was quiet, she said.

The local secondary school, St Catherine’s, is a thirty-minute ride on a school bus that picks up young people from the surrounding area. Penny tells me this bus ride is where many friendships are made.

—So when he starts at St Catherine’s, Robbie starts getting the bus with the rest of them, including our Elsie. She’s a bit older, year ten by then, and sits at the back with all her mates, listening to their Walkmans and that. She says no one picked on him, no one took much notice of him really. This little quiet boy. Then one day, when they go up the hill past the farm where Danny Greenwell lives, to pick him up, Danny sits next to Robbie. That was the start, as far as I know anyway.

Penny explains that she doesn’t know a lot more about the relationship between Robbie and Danny. She saw them around together over the next few months, but paid them little mind.

—I used to see them round the village a lot more, especially on the weekends – wandering off to the pond or, as it turned out, up to the kilns. I never thought much of it, to be honest. I was glad the lad had made a friend. I was glad that the other one, Danny, had found someone too. I thought it was good for both of them.

Penny tells me that she wasn’t aware of any interaction between Robbie and Danny and Sidney Parsons, their eventual victim.

—I honestly think if they’d been after Sidney from the start, we would have known about it. I would have heard something in the queue at the supermarket or after church. Folk looked after their own round here, especially a kid like Sidney Parsons.

From what has been made public about the case, Sidney Parsons was relatively popular around Ussalthwaite; certainly everyone knew who he was and looked out for him on account of his epilepsy and a learning disability.

—Back then we didn’t know what to call it. I don’t know the right words and I don’t want to upset anybody. He was a bit … slow, you might say? A bit delayed? He was a smiling, happy sort of boy, would do anything for you if you asked him. You know the type? Lots of people made sure no one took advantage – cos they do, don’t they? People take advantage of folk who are a bit … well … less fortunate. It wasn’t like Sidney didn’t have friends of his own though. He hung around with poor Terry Atkinson from Butterwell Court.

We’ll come to what happened to Terry Atkinson in due course. For now I want to keep things in relative order. Robbie arrived in the village in February 1995 and soon made a connection with Danny Greenwell. A few months later, in the summer, some strange incidents took place in the village.

—Oh it was like a biblical plague, right here in the village. Horrible things. I’ve never seen anything like it.

Penny’s talking about an infestation of flies that descended on Ussalthwaite overnight, sometime in June 1995.

—We couldn’t sleep; they kept setting off the security light, there was that many of them. I’ve never seen anything like it in all my life – thousands of them all over everything. Those citronella candles you burn on holiday were changing hands for hundreds of pounds; the shops were all out of fly spray. We all had to stay in with the windows closed – they would get in your hair, your mouth if you dared go outside. Everyone was tense the whole time cos you always felt like there was one crawling on you. We looked out of the window and saw them swirling in the sky like a flock of birds. I get the shivers thinking about it now.

Our Elsie says there was a horrible day on the school bus. She said that there was a group of lads who sat at the back – older ones, and they were always shouting things at Robbie and Danny. She says that one of them, she can’t remember who, turns round and tells them if they keep going, they’ll be sorry.

—Robbie or Danny said this?

—Right. She says these lads all start laughing, and the rest of the bus was laughing too. But then suddenly it slows down, the engine stops and everything goes dark.

—On the bus?

—On the bus. It was them flies; the bus had driven into a big cloud of them, and they were all over the windows. She said it was like a moving fog, millions of little bodies slithering all over each other. She thought they must have got into the engine or something.

Then of course, poor Sidney Parsons starts fitting, doesn’t he?

—What kind of a fit?

—He starts shaking, and the kids round him are screaming. He was lucky he had his mate with him, Terry Atkinson, who knew what to do – looked after him until the driver gets the engine going again. Elsie said he had the windscreen wipers going to shift them. They finally managed to get Sidney to the hospital and the kids to school.

Then, after a few days, they were gone, the flies. Folk were sweeping great big clods of them from their windowsills and off their ceilings for about a week afterwards.

It happened again. Just a few months back. Twenty-six years later. On the anniversary of that poor boy’s death – another load of flies. Horrible. Just horrible. It goes to show that there’s summat not right going on. The flies come back, and then that poor man. What’s the common thing here? The kilns, that’s what. That bad place.

It was reported at the time that, on the twenty-sixth anniversary of Sidney Parsons’ murder, Ussalthwaite was once again engulfed by a plague of flies. The official explanation was the flooding of the River Fent, which flows through Ussalthwaite; the standing water left on the moors, and the lack of activity there and on the river during lockdown, allowed the concentration of a mating swarm of a non-biting midge known as the chironomid.

Let’s go back to 1995.

—It wasn’t long after that the disturbances began at the Hartley’s place. Word gets around quick in the village, so soon everyone knew about them.

—When did you first hear about what was happening there?

—I knew the folk next door to the Hartleys. They were an older couple: Fiona Brown and her husband Henry. Henry, the poor soul was bed-bound; on his way out.

I remember chatting to Fiona after church one Sunday once the schools had gone back. She was pale, drawn, all of a flutter. Not had enough sleep, poor thing, and she said it was all cos of the racket.

—From next door?

—That’s right. She said she’d been hearing all sorts, the most ungodly din. Great, big, clomping footsteps she says. But not on the floor. They was all over the walls, like someone’s walking on them. It went on and on, all bloody night. She didn’t sleep a wink.

—Did the Browns complain?

—I think, what with the boy coming and his situation, they didn’t want to make a fuss, you know? Maybe it was him playing up, but with what had happened to his parents, and being in a strange place and all, that was understandable, wasn’t it?