Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Firefly Press Ltd

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

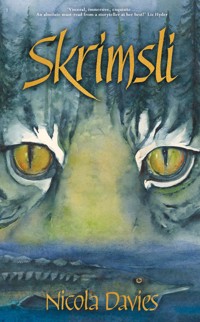

Who you are if you've never seen another face like yours? Where do you belong if you don't know where your home is? What do you call yourself when others call you 'freak'? How can you be brave when you are full of fear? Why would you choose purpose over love? Skrimsli is the second fantasy adventure from author Nicola Davies set in a world where animals and humans can sometimes share their thoughts. It traces the early life of Skrimsli, the tiger sea captain who stole readers' hearts in The Song that Sings Us. He and his friends, Owl and Kal, must escape the clutches of the tyrannical circus owner Kobret Majak, and his twin assassin-acrobats, then stop a war and save the ancient forest, where the Tiger, and the Owl are sacred guardians. Skrimsli and his friends are helped by the Palatine, desert princess and her eagle, a chihuahua who thinks she's a wolf, a horse with heart of gold and the crew of a very unusual ship. This is a story full of excitement and danger, that explores themes of friendship, loyalty, identity and love, in the context of some of humanity's toughest problems.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 549

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Praise for Yoto Carnegie Medal nominatedThe Song that Sings Us

‘A magnificent adventure story.’

The Scotsman

‘Career-crowning.’

Observer best children’s books of the year

‘It balances the line between grief and wonder, hope and fear. I was chilled, heartbroken and felt reflected in it too, but the story, it is glorious and visionary with epic adventures and beautiful characters! I loved it so much.’

Dara McAnulty

‘A gripping adventure that will set your heart racing and stir your soul. Utterly unputdownable, packed with unforgettable animal characters (humans included) … Vivid and original, this is a story for now.’

Helen Scales

‘Beautiful. Heart-wrenching, gripping, strange and glorious. Jam-packed with brilliant characters and big ideas. Loved it! I am also now in love with a sea-faring tiger captain…’

Liz Hyder

‘Beautiful, lyrical and fast paced. The Song That Sings Us is a story of our time. It parallels the urgency of the challenges we face to protect this world.’

Gill Lewis

‘Wild, powerful and passionate, The Song that Sings Us is an extraordinary weaving of fierce action and tender poetry, a heart-wrenching yet hopeful symphony of the threads that connect all life on Earth.’

Sophie Anderson

‘… a hyper-imaginative book, bringing to mind the complete works of Philip Pullman with their sprawling cast of animal familiars, Yan Martell’s Life of Pi with which it shares a tiger on a boat – although this one has ‘fur like fire and soot, whiskers like strands of white wire, green eyes like the aurora’.’

Jon Gower, Nation Cymru

‘Captain Skrimsli!’ the woman calls out over her shoulder, and the others take up the cry. ‘Captain Skrimsli!’ Even the rowers have stopped their singing now, and instead call out one word. ‘Skrimsli! Skrimsli! Skrimsli.’ What does this mean? Is it an instruction that they need to follow? Suddenly the cry of Skrimsli breaks down into cheers and the crew who line the gunwales step back. In their place is a huge tiger. ‘Hold on tight!’ the green-coated woman yells. ‘The captain will get you aboard!

From The Song that Sings Us by Nicola Davies (Firefly 2021)

‘Skrimsli was not a character I planned. He happened without me having to think about him first. And then he almost took over The Song that Sings Us, so it seemed a good idea to give him a story of his own, and to tell the history of how a tiger becomes a talking sea captain!’

Nicola Davies

DEDICATION AND THANKS

This book is dedicated to everyone who struggles to find a place where they truly belong.

With thanks (again) to my first audience: Jackie Morris, Cathy Fisher and Molly Howell

And to my husband Dan Jones for … everything

Who are you if you’ve never seen another face like yours?

Where do you belong if you don’t know where your home is?

What do you call yourself when others call you ‘freak’?

How can you be brave when you are full of fear?

Why would you choose purpose over love?

The tiger and the sturgeon and the owl are the keepers of the forest. Each must speak to each to keep the forest whole. But the owl, who speaks to both the river and the trees, is the greatest keeper of them all

Contents

1

Owl

Death and Birth

Night was Owl’s time. He could move around the circus like a shadow, unseen and undisturbed. He could rest amongst the animal pens in the Menagerie Marquee, listening to the rumbling talk of the elephants and the comforting snores of the sloth bears. He could poke sticks into the little stove and cook whatever food he’d scavenged from the deserted mess tent. There was no one to gawp and jeer and call him a ‘Freak of Nature: The Human Boy with the Face of an Owl!’

But tonight, Owl’s peace was disturbed, because Narastikeri, the old tigress, was dying. Everyone in the circus came to take a look at her. Saldo and Zuta, the trapeze artists, were first, Zuta sobbing into a lace handkerchief. Old Galu Mak, the dog trainer came next and whispered to the tigress through the bars, ‘You are crazy-pretty pussy cat, Madam.’ The cooks and the stable hands, the wardrobe master and the maintenance ladies, the musicians and the master of provisions, all remembered the days when Narastikeri had been the star of every show. They all filed past, peered sadly at the withered creature panting on the dirty straw, and shook their heads.

Even the ‘jantevas’ – the roadies, whose job it was to lift and carry and fix, and who treated everyone with contempt – piled out of their caravan and shuffled past to pay their respects. They clutched their caps in their big hands, mumbling like small boys at their auntie’s funeral.

Everyone took Narastikeri’s dying as a very bad omen. Another sign of the poor luck that had dogged the circus since they began this ill-fated tour. Majak’s Marvellous Circus had been sent to the mountain provinces by the Nordsky Department of National Pride. But mountain people didn’t like circuses and the weather had been harsher than anyone had expected, with heavy snow from October. The circus had ended up stranded in a small town, at the end of a broken train line, in a sea of snow. People talked of running away, but where was there to run to? Dalz and Tapis, the trick riders, had tried it two nights ago. They had vanished, with four of the best horses and a litter of beautiful hound pups that Galu Mak had planned to add to her act. Just this morning two of the horses had come back lame and spooked, without riders or pups.

‘We’re gonna die here in these damn mountains,’ Galu Mak had said.

Narastikeri’s procession of visitors continued. Owl watched them from his hiding place under the stack of benches behind the dying tigress’ cage.

The last to make a visit were the boss himself, Kobret Majak, and his bear, Karu. Kobret was almost as big as his bear, a huge man with a face as hard as a cut diamond. Karu shuffled behind him, unkempt and dead-eyed, so much under Kobret’s control as to have no real mind of his own. All the other animals drew back as Kobret and his bear passed by. They carried fear with them like a cloud.

In front of his audience Kobret Majak played the part of the jolly ringmaster. He claimed that kindness and reward were all he used to train his animals. But it was lies. Kobret possessed the power of Listening, the ability to tune into animals’ minds. He liked to deny it because it had fallen out of favour with the Nordsky Government. But he had it alright and used it to force his way into the minds of animals, to implant pain and terror. That was how he made them do the tricks that made audiences gasp in wonder.

Listeners like Kobret could not enter human minds. So he used the claws and invincible strength of his slave, the bear Karu, to terrify the humans too. Animals and people only had to look at Kobret Majak and Karu to feel afraid.

Narastikeri was almost beyond Kobret’s cruelty now. She closed her eyes and her belly heaved, trying to push out the cubs she’d carried for too short a time. It was obvious that she was slipping away, but Kobret showed no kindness or concern for the tigress who had been famous for her beauty and skill. As usual, all he thought about was money. He turned to Akit, the stable hand whose job it was to see to the care of the animals and growled.

‘I paid a fortune to get her mated to that white tiger!’ Kobret said. ‘These cubs were supposed to pay my bills.’

Karu turned to Akit and bared his teeth. The man cowered.

‘Narastikeri’s old and sick, Boss,’ Akit whispered. ‘Maybe she shouldn’t have been carrying no cubs.’

‘How dare you criticise me?’ Kobret roared. ‘Don’t you know how much money people will pay to pet a white tiger cub?’

Owl thought that Kobret would hit poor Akit, who raised an arm to protect himself.

‘No, no, Boss. Course not.’ Akit paused. Owl could see how much Narastikeri’s state upset him: enough to risk Kobret’s anger and Karu’s claws. ‘There is an animal healer in the town who we could ask for, Boss,’ Akit suggested quietly.

‘And what will that cost?’ Kobret hissed. ‘No. I’m not throwing good money after bad.’

‘Could I have the key to her cage then, Boss?’ Akit went on bravely. ‘So I can make her a bit more comfortable?’

Kobret turned to the stable hand and poked him in the chest with one thick finger, while Karu stood close, snarling to back up his master.

‘Comfortable? This is an animal! It is a mute, dumb beast. It’ll be dead by morning, when I’ll take the last bit of profit from it that I can: its skin. You have other work to do. Now get out, before Karu makes a meal of you!’

Karu stood up on his hind legs, towering over the man, who staggered backwards, then ran.

Kobret kicked the bars of the cage, cursed, and stalked out of the menagerie, grumbling and growling, just like his bear.

At last, apart from the usual sound of ropes and canvas arguing with the wind, it was quiet. The people had gone back to their cozy caravans to moan about this disastrous tour. The tears they cried over Narastikeri were partly shed for their own plight. Owl guessed that most of them had forgotten about the dying tigress the moment they’d left the tent.

Owl crept from his lair and sat looking through the bars at Narastikeri. Her fur was dirty and matted, and her breathing was irregular. Under her closed lids her eyeballs rolled. She gave a small growl of pain and bared her broken, yellow teeth. Years of Kobret’s cruelty had made the old tigress mean, and Owl had always been afraid of her, but his heart hurt to see her suffering like this. So he shuffled closer, then closer still, until at last he could reach out a hand to touch her head. She flinched a little at first but then she let him stroke the stripes between her eyes.

Kobret kept the only key to the cage, so Owl could not get inside, but he gave what small help he could. He fetched clean rags and water and reached through the bars to clean her crusted eyes and drip water onto her lips. But he could do nothing to help the cubs. One by one, as the night went on, they appeared, each too small and weak to take a single breath. Narastikeri tried to lick them into life, but she was barely strong enough to lift her head. Owl’s arms were too short to reach any of them – to clear their mouths and noses, or massage breath into the tiny bodies with their faint fuzz of pale fur.

The sixth cub was the last. It was not pale like the others, not one of the ‘litter of beautiful white tiger cubs’ that the Majak’s had already advertised on posters all around the snowy town. This one was the colour of fire. But it too lay still and did not seem to breathe. Owl looked at it and wondered how something so bright could not be alive.

Narastikeri managed to open her eyes and look at her last, flame-coloured child. She let out a long, low moan and Owl felt her grief envelope him. How could she be comforted, he wondered. The only comfort he knew himself was to escape to the place he kept safe inside, the great green forest where he had been born. In his mind he could plunge into its greenness, not just a colour but a feeling of home, of peace and belonging. Its trees were huge, their branches reached to the sky, their roots spoke under the brown earth. He had lived in one of those great trees, in a shelter woven out of stems and twigs like a giant nest. Many creatures thrived there, bears and owls, tigers and wolves. Ancient fish, huge sturgeon, swam in the deepest pools of the slow rivers.

In that place Owl had not been a freak. He had fitted like an eye in its socket, or a leaf bursting from a bud. He remembered arms rocking him and whispering words:

‘The tiger and the sturgeon and the owl are the keepers of the forest. Each must speak to each to keep the forest whole. But the owl, who speaks to both the river and the trees, is the greatest keeper of them all.’

Where was that forest now? Somewhere to the north was all he knew, because he had been stolen from it when he was so small. All he had to guide him was the name of his village, Bayuk Lazil, and the little wooden sturgeon on a string around his neck. He wrapped his fingers around it and whispered the words Bayuk Lazil like a spell. This was his route back to that place of green and belonging. Owl wished he could take Narastikeri with him, but he could not. Immersed in the comfort of his green home, Owl fell asleep.

He was woken by the shouts of the jantevas. It was light, the grey-blue light of a snowy landscape. In her cage, Narastikeri was quite still. The cage had been opened and the jantevas were swarming around her like eager maggots.

‘Get out of the way, Freak Boy,’ they told him. ‘We got a dead tiger to skin and get rid of.’

Owl scuttled back to the safety of the stack of benches. Even in death the tigress was formidable; it still took five men to move her out of the tent to skin her in the open, then throw her remains into a waiting cart. The sixth was left behind to clean out the cage and to scoop the dead cubs into a sack. One by one they dropped like wetted lead, but as the big hand grabbed the last one, the orange cub, it squeaked. It was alive! Owl knew the man had heard it too.

‘Leave the fire-coloured cub!’ Owl called. ‘Please!’

None of the other jantevas would have bothered to answer, but this was the one called Brack, who had a split in his lip. His brothers teased him and called him ‘freak’, the same word they used for Owl.

Brack shook his head. ‘Orders!’ he said. ‘Orders.’

‘Where will you take them?’ Owl asked.

‘Ground’s too ’ard for burying,’ Brack lisped in reply. ‘Boss says drop ’em through the ice on the lake.’

He hurried away, with the sack over his shoulder.

Owl waited for the sound of the cart’s wheels crunching over the snow before he moved. He didn’t want the jantevas to see him. Then he hurried from the tent, turning his eyes from the bloody stain on the snow where the tigress had been skinned. Owl knew a short cut, a path the townspeople used, that ran from the perimeter fence around the circus, between the trees, down to the jetty at the lakeside. That would be where they’d take Narastikeri and her cubs. Owl ran along it, his short legs struggling through the snow, his arms flailing. But even his fastest pace was much too slow. By the time he had reached the lake, the jantevas were on their way back and their cart was empty. He was too late. A jagged hole in the ice showed black water where the bodies had been dumped. He lay down on the jetty and stared into the ice hole. Nothing. Narastikeri’s body must have sunk straight to the bottom. He leaned further, trying to look through the blackness. There! There! His heart skipped; the sack had caught on something below the surface. He could see it still floating, almost within reach.

How long would a sickly newborn cub survive in ice-cold water? Not long. Heart racing, Owl wrenched a fallen branch from the snow-covered tangle of undergrowth and struggled with it to the jetty’s end. He took two goes to hook the sack with the crooked, unwieldy thing. Then more long moments to loosen the knotted string that tied the neck of the sack. Finally, he reached inside and pulled out the fire-coloured cub.

It was a male, or would have been, but it was stone cold, still and limp. Owl sat down. He had thought himself hardened beyond crying, but tears came into his eyes now as the cub lay like a rag in his lap. Owl felt defeated, more beaten than ever before. Then he remembered something he’d once seen Galu Mak do with a newborn pup that hadn’t breathed. She’d held the little creature by its back legs and swung it round. He remembered how the pup had spluttered into life. Owl stood up; he held the cub dangling by its back legs. It seemed so brutal, but he had to try. He swung the cub around his head. Water flew from its drenched coat and its small tail flopped about. He swung again. Once, twice. Nothing.

And then, on the third swing, a sound. A tiny, spluttering cough; a pink mouth opening to let out a noise more worthy of a mouse than of a tiger. Owl thought it was the most beautiful, important sound he’d ever heard. Owl rubbed the cub’s fur to fluff it up, then put the cub inside his shirt, next to the warmth of his skin and began to trudge back up the snowy track towards the shelter of the Menagerie Marquee. As he walked, he felt warmth slowly spreading from his body to the cub’s, but it was very still, only just alive. Owl realised that rescuing the cub was foolish if he couldn’t find a way to feed it! However would he do that?

By the time he reached the menagerie, Owl had come up with no answers, and was beginning to feel defeated again until he saw that Taze was waiting for him at the entrance. Taze was the old hound who had belonged to the stunt riders Dalz and Tapis. The handsome pups they’d taken when they rode off into the night had been hers. She trotted up to Owl and pushed her nose into his shirt where the cub was hidden, as if she knew there was another baby that needed her help. In response, the cub squirmed and gave a demanding squeak, sensing the prospect of his first meal.

Owl scratched the soft place behind Taze’s ears and she closed her eyes in pleasure.

‘We will raise a tiger, you and me!’ Owl whispered to her. The cub squeaked again: now that he had a chance, he seemed quite determined not to die. Suddenly Owl felt determined too; this cub would live and somehow Owl would protect him from Kobret’s cruelty. As they walked in under the shelter of the canvas canopy, Owl found himself smiling with pure joy. He was not alone anymore! A wild thought flew up from the green place inside the boy’s heart, an impossible dream.

‘We will find the green, you and I,’ he told the cub. ‘We will find my old home, where Owl and Tiger are the forest keepers.’

In answer the cub gnawed at his finger with its small toothless jaws.

‘You are a monster!’ Owl laughed and a word came to his lips from the language of that long-lost green place. ‘Monster,’ he said. ‘Yes, skrimsli. Skrimsli! That’s your name.’

2

Kal

Dark Stars

Kal ran beside the horse, a flurry of snowflakes flecking face and body, hooves ringing on the frozen ground. Kal could smell the horse’s fear: fear for himself and fear for his human companion.

‘Run faster, Luja. Leave me behind,’ Kal wanted to tell him. ‘It’s me they want, not you!’ But Kal had never had the knack of entering a horse’s mind; they had always understood each other well enough without that. In any case, Kal knew Luja would not go on alone.

The pursuers were not yet gaining on them. The wheels of their horseless chariots were no match for this rock-strewn ground. But a bullet had already grazed Kal’s shoulder; it was just a matter of time before they grew close enough for another, more damaging shot. Long before nightfall gave them cover, the two assassins would be on them. Then Kal would be killed and maybe Luja too. Even if it drew more gunfire, riding was their only chance.

With the next running step, Kal placed a hand on Luja’s shoulder, pushed off with the left foot and slung the right over Luja’s warm flank. Low across the horse’s neck, with the strands of his mane streaming, Kal felt the ripple of muscles beneath the horse’s skin. In spite of their danger, there was that familiar surge of exultation that always flowed from Luja, as they leapt forward in a gallop that no other horse on earth could catch.

Bullets zipped around them, tearing the air with small ripping sounds. Luja’s eyes showed white rims of fear yet, somehow, he found more speed. Soon the shots bit the turf behind his heels quite harmlessly.

Up ahead rose the sacred mountain, Tamen Haja: a huge ridge of rock, like the mane of a giant horse rising from the grassy plains. Its sides were cut by a hundred deep ravines made by a million years of spring meltwater. Kal had often run to that kingdom of rocks and streams to escape what other people wanted. Do this! Go there! Be like this! Don’t be like that! Kal had pleased no one and fitted nowhere. On Tamen Haja there were only the demands of wind and water and sky.

One place was Kal’s favourite refuge. The narrowest of gullies, cut where water had found a fault in the rock and widened it. There was a cave there that made a perfect hiding place. But how to reach it undetected by these two persistent followers? There was no cover between here on the plain and the slopes where the network of ravines began. The assassins would track their path easily. If only the snow would fall faster and hide them now! Instead, the sun dropped below the cloud and lit the plain with bright slanting light, illuminating everything in dazzling detail!

Dazzling! Dazzling…That was the answer.

‘This way, Luja, into the sun!’

As if he’d understood Kal’s words, Luja began to swerve, galloping straight into the sunset. Kal glanced back and saw the assassins trying to shade their eyes from the glare. To them, horse and rider had now vanished into the blinding light. Kal urged Luja to go faster up the slope ahead, and then turned him at right angles to head behind a low ridge that ran all the way to the mountain. The pursuers would assume that they were still heading west. By the time the sunset faded, Luja and Kal would be covered by the grey bloom of dusk.

Warmth from the deep heart of the rock kept the pools in the gully bottom unfrozen year-round and started spring grass growing early. Luja sucked in the sweet water and cropped some tufts of grass. By the time they were picking their way up the side of ravine, the last light was fading from the sky. It took all Kal’s skill and patience to help the horse navigate the narrow route and persuade him to stoop low enough to get inside the cave. But here they were at last hidden beneath a vaulted roof of rock. A fissure opened to the rear of the cave, a crooked crack that led to open air three hundred feet above. This made a chimney that would guide their smoke up to where the air moved swiftly, whisking away any tell-tale plume. Kal had been visiting this secret spot for years and always left a little store of sticks and kindling tucked away on a rocky ledge where damp couldn’t reach. Kal’s fingers found these now in the dark, and the flint and steel wrapped in oiled cloth. Friendly flames sprang up and yellow light filled the cave.

A dark patch of blood stained Kal’s shirt sleeve which peeled away to reveal a scratch half a finger long across the muscle at the top of the arm. Luja stretched over to snuffle at it with his soft nose, ears back.

‘It’s fine,’ Kal told him. ‘It’s not bleeding.’

Luja snuffled again.

‘It’s already scabbing over,’ Kal reassured him. ‘I’ll bind it with a strip of cloth. It’ll be fine.’ Kal tore a strip from the hem of the shirt and bound the wound tight.

‘There! See?’

Finally, the horse ceased his inspection and curled his legs beneath him like a cat soaking up the warmth from the fire. Kal shuffled closer to him. Everything about Luja was a comfort: his size, his warmth, his smell. Kal breathed it all in and the dam that had held back the horror of the day crumbled. Kal’s whole body shook as the memory replayed.

Kal and Luja had been travelling to Talo Numikalo, the ancient sanctuary of the Horse people, where Kal had been raised. Kal was the child of a Herring father and a Horse mother: a wild man who vanished back to sea and a nomadic shaman who left as soon as Kal was weaned. No one had wanted Kal, a dark little creature who cried easily and snarled readily. Like a troublesome parcel, Kal had been passed between various outposts of Herring people family. And when that didn’t work, Kal was sent to Talo.

Talo Numikalo was part monastery, part refuge. It was an ordered community of people and their horses, all with deep knowledge of the Sea of Grass. Kal had rebelled against its calm routines and quiet duties because rebellion was a habit, a strategy for self-protection. But the Talo residents had better things to do than scold and punish an awkward child. They let Kal be and watched at a distance to see what would happen. What happened was that Kal found horses and loved them. Horses never asked for or expected anything, they just accepted. Kal understood them without thinking. Left free, and alone except for the horses, Kal thrived. Talo became the nearest Kal had to ‘home’.

Talo was an ageing community, as few young people now wanted to know the secrets of the Sea of Grass, the medicinal properties of its thousand plants, or how the land and ocean worked together to keep the grass sea lush and green. They didn’t even want to know the old way of working with the sea’s beautiful wild horses; nowadays people preferred the easy force of metal bits and leather bridles. So the Talo community was awash with old knowledge with nowhere to go, and some of it flowed into Kal in spite of the instinct to resist.

When Kal left childhood behind and became a person strong enough to haul a lobster pot or a creel of herring, Father’s relatives decided that the ‘troublesome parcel’ could at last be of some use. So Kal was only free to spend time at Talo between the end of winter fishing and the start of spring planting.

It was a long journey from the Herring people to their old friends. Kal and Luja had begun in the afternoon of the previous day and travelled through the night with few rests. The weather was still cold. Kal was glad of the cap of felted wool and the padded yellow coat that the Herring relatives found so outrageous: gifts from Kal’s last visit to the Talo community.

The final part of the journey passed quickly, because Luja wanted to run and was happy to carry Kal on his back. The Grass Sea had streamed around them, coming to life at last after the long winter, even though snow still lay in a few shaded hollows. Flocks of small birds swarmed over its surface, huge yellow bees buzzed among the earliest flowers and arrow-shaped formations of cranes called above, as they headed north.

Kal and Luja played their usual games. The horse would turn to nip at Kal’s feet, which was Kal’s cue to swing feet and legs to the other side. Luja would give a little buck as he sped along; this was the cue to slide under Luja’s belly and cling there, head almost hitting the ground as it rushed beneath them. Best of all was when Kal stood on the horse’s back as he galloped, arms spread wide as if they were wings that could carry them away.

It was joyous to return to Talo after the winter of rough sea, hauling nets in the dark and taking baskets of fish to market in various rickety little carts. As usual, Kal had been scolded for everything: hair, clothes, behaviour, life prospects, ideas, speech. It was like being a bush constantly attacked by pruning; there was never any way to grow. Riding over the grassy plain, Kal was so busy soaking up the sense of freedom that the smear of smoke over the low thatched buildings went unnoticed. Only when Luja gave a low whicker of alarm and voices reached them on the wind, did Kal see that something was very, very wrong. Luja snorted, ears flat, nostrils wide, sucking information from the air. Kal slid from his back, down into the grass and crouched low to peer between his legs.

Snow had begun to fall in swift spurts, like the whisk of a curtain across the scene. Still, Kal could see enough to be filled with horror. Flames leapt through the roofs of the buildings. Horses screeched in terror, wheeled around and fled, vanishing into the smoke. The people were not so lucky. Talo Numikalo residents ran to escape the fire and were calmly struck down by two identical attackers. They were tall and slender, dressed in close-fitting garments and dark face masks. They moved with precision, more like machines than humans. Each carried foreign weapons, long guns slung over their shoulders that caught the light. But they did not use these; instead, they picked off the fleeing Talo residents with Erem crossbows and finished them off with clubs that fishermen used to kill big fish.

None of the Talo people fought back; they were healers, artisans and shamans, not warriors. They could not resist these killers who were so expert, so coldly calm. Any survivors who managed to evade the first round of slaughter were pursued by the two killers in their small horseless carriages.

Kal was close enough to recognise some people through the shifting veils of snow. Nurmi, who had tried to teach Kal to make healing teas from a hundred different plants when all Kal wanted to do was run with the horses; Puun, who showed how flatbread was made in smooth wide rounds, though Kal had only managed to burn it; Yurti and Laiden who had introduced Kal to Luja as a newborn foal.

At last, the screaming stopped. There was no one left to scream. But the killers had more to do. They dragged two bodies from one of the horseless chariots. These were dressed in the waxed overalls and peaked caps that every Herring person wore to sea. They gave one body a crossbow and the other a club, then positioned the bodies carefully. Kal realised that they were trying to make it look as if these Herring men had attacked Talo and had been slaughtered in return. The killers stood looking at the carnage as if over a well-ploughed field. Then they greeted each other with a strange little gesture, a kind of hand-flapping wave, the sort of thing two children might do: twins with a secret language of words and signs.

That was when they noticed Luja and Kal, half hidden in the grass. Only the crack of the rifle shot and the wetness of the blood had woken Kal from the trance of horror. Just in time, Kal and Luja had turned and run.

The fire in the cave glowed warm but still Kal shivered. But for the lucky glare of the setting sun, they would be lying now with snowflakes settling on their open eyes. Kal drew closer to Luja, breathing to match his steady breaths until there was enough peace to be able to think. Somewhere in the terrible images that crowded Kal’s mind there were clues, information.

Who were the attackers? Who would gain by killing a bunch of old Horse folk. And why did they want to make it look as if Herring people had done the killing? One thing was certain and that was that they were not thieves or madmen. Killing was their business. Kal shivered; professional assassins would not give up. They might be creeping through the night now, this minute. Hiding alone in a cave was wrong. Kal and Luja must return to where they were just one horse and rider among many. Perhaps they could find out what was going on, what all this meant.

As soon as the moon rose, Kal doused the fire and roused the dozing Luja, who was reluctant to leave the warm cave and go back into the chilly night. Kal whispered in the horse’s ear, words of nonsense and affection and his temper was soon restored.

They picked their way along the river and paused at dawn to rest a little. Kal scanned the ravine and listened: there was nothing to hear but water and the morning cries of birds; nothing to see but rocks and branches, scraps of sky and Luja’s pale coat gleaming in the early light. That coat! Milk white with stars made from darkness was how Yurti always described it. There’s no horse like him in all of Erem. The assassins would spot it from a mile away.

There were still some fruits left on the mayoban bushes that grew in thickets by the flowing water. Kal gathered them and rubbed them into Luja’s coat. Their dark brown juice changed him into just another grubby, dark horse. Luja snuffed at the smell of the juice in disapproval.

‘We need to be disguised,’ Kal told him.

The yellow coat and tall felted cap were just as distinctive, of course. Kal shoved the coat deep into a crack between two rocks. The felt cap sank in the river and with it the ribbon that tied Kal’s long braid. Kal peered at the reflection in the pool, a wary face and a cloud of dark hair. As unfamiliar as always but at least now it would not match what the killers had seen.

They would head for Turgu, the main port of Erem, where there were ships and crews from Nordsky, Rumyc, Danet and even further; both Herring and Horse people came there to buy and trade.

‘We’ll hide in that crowd,’ Kal told Luja. ‘We’ll find Havvity. She’ll know what’s going on.’

Saying Havvity’s name out loud took away a little of the horror of the previous day. Havvity was the closest thing to a real sister that Kal had: not a blood relative but the niece of Kal’s father’s first wife, Meghu. In spite of the fact that Meghu hated Kal as ‘the child of that horse witch’, Havvity and Kal had grown close. Havvity was sure and steady, always kind when Kal was tormented by dark moods and self-doubt. But since the unplanned appearance of Roko, Havvity’s baby son, Kal had repayed a little of the debt of her kindness, by defending her from Meghu’s cruel disapproval. This and the rush of fierce protective love that Kal felt for Roko had brought the two young people close.

Kal pushed away the thought that the pursuit of the two assassins might force a flight beyond the borders of Erem, far from Havvity and Roko. For now, the horror that they’d witnessed and what it meant could be buried in the beat of Luja’s hooves.

At sunrise on the second day they reached the low plateau of short, horse-grazed turf that tilted gently towards the sea at Turgu.

‘Now my friend,’ Kal whispered to Luja, ‘run like the wind!’ Tired and hungry though he was, Luja broke into the loping canter that he could sustain for miles. Blue sky showed between the clouds and small herds of wild horses dotted the green. Luja sniffed the air to gather their news. It seemed impossible that anything really bad could happen in such a place.

But as they entered Turgu, Kal knew at once that something was wrong. The air crackled with fear. The busy, cheerful clatter of the town was gone, replaced with silence and the banging of doors. Householders were covering their windows in weatherboards, as if a great storm was on its way. In the market square, stall holders were packing up, tight lipped and unsmiling, and shops were drawing down their blinds. Kal managed to buy a loaf from a baker as he shut his door and stood in the shadow of a tethering tree to share it with Luja and watch what was happening. Horse people were all leaving town in a hurry, horses, ponies and carts clattering over the cobbles in their haste. All around, black looks flew from Herring to Horse and back.

A Nordsky horseless chariot, like a big green fish-box on wheels, came into the square. It coughed black smoke from a pipe in its rear and something growled under the lid at its front. It was like the chariots that the assassins had used, but uglier. The driver steered the thing slowly up the road, while a man stood up in the back with a megaphone. He wore a black uniform with a red symbol on its collar. Two Nordsky soldiers in green uniforms walked beside the chariot with rifles ready, staring left to right as if they’d like to shoot everything they saw. Megaphone man repeated his message over and over again.

‘Attention all citizens. Turgu is now under the command of Military Forces. You have nothing to fear. We will restore order, control the conflict and prevent war. We order all Horse people to move out of the town at once. Herring residents must keep off the streets. Stay in your homes. Remain calm.’

What conflict? What war? The green uniforms were Nordsky army, who always found some excuse to flex their muscles in Erem. But who was the one in black? He spoke with a Rumyc accent. Why could Nordskys and Rumycs tell Erem people what to do? A cold bubble of fear burst in Kal’s belly; would Roko and Havvity be safe in a town at war?

Following behind the chariot was a Herring boy in a waxed sea-coat, with a hammer, a bag of nails and a pile of small posters in a bag slung over his shoulder. Every few yards he stopped to pin a poster to any wall that would hold a nail. The boy nailed one to the door close to Kal and Luja. He glanced nervously at Kal and gave a quick smile.

‘Always liked Horses me,’ he said. ‘But there’s them ’ere what doesn’t, right now. I’d make myself scarce if I was you. Sharpish!’

As the boy moved on up the street Kal read the poster he had put up.

Wanted for Murder at East Cove

Rider 15-17 years. Male, wearing traditional

Horse headdress and yellow coat.

Pale horse with distinctive spotted pattern.

Reward offered for information leading to capture

Reports to Commander Lazit,

Automator Forces, Turgu Garrison

Kal’s heart froze. Wanted for murder? East Cove folk were Kal’s father’s people. They had never been kind, but Kal didn’t want any of them dead! What was happening? How was the world unravelling so fast? Fear spread through Kal’s body now, like ice crystals blossoming across a windowpane. Kal grabbed the poster from the nail and scrunched it into a pocket.

‘Come on, Luja,’ Kal breathed. ‘We need to get off the street. We need to find Havvity.’ Kal darted down the alleyway that led to the Black Fish Café, where Havvity worked for her Aunty Meghu. Luja’s hooves scraped and echoed on the cobbles and the Black Fish sign swayed a little, announcing ‘the cafe that never closes’. But it was closed. Kal knocked on the door. A small window, two floors above the cafe opened and Meghu popped her head out. Kal hoped she hadn’t seen the posters.

‘Oh, it’s you and your stinking beast!’ she cried. ‘Go away!’

‘Is Havvity in?’ Kal called. ‘How is Roko?’

‘Like you care!’ Meghu snarled. ‘Haven’t you heard? Your lot killed everyone in East Cove who wasn’t at sea last night. Go away!’ The window slammed shut.

Everyone in East Cove? Not a murder but a massacre! Just like Talo. Someone wanted to set Horse against Herring and Herring against Horse with lies. Kal pulled the poster out and looked at it.

Wanted for murder…

Rider 15-17 years. Male, wearing traditional Horse headdress and yellow coat.

This lie did two jobs: it blamed the killing of Herring people on a Horse; and it silenced the one person who knew the truth. Kal saw now exactly why the assassins had given chase!

Luja’s hooves made nervous clopping sounds on the cobbles. His ears swirled, picking up the sound of running boots and angry voices just before Kal did. At the end of the alley, an old man appeared pulling at the bridle of a mouse-coloured pony. The creature was lame in its right hind foot. The man was terrified. The shouts grew louder. The man tried to get the pony into the alley, but they were suddenly surrounded by a mob of Herrings, men and women. The Herrings carried objects that had come easily to hand: a rolling pin, a walking stick, a butter pat, even a wooden doll to use as weapons. Ordinary objects and ordinary people turned to evil.

Kal and Luja fled down the alley as the mob advanced. But the road beyond was filled with rows of marching soldiers, each black uniform carrying the symbol of a red fist closing around the earth. Kal and Luja were trapped.

A hand landed on Kal’s shoulder and Kal spun round in terror. It was Havvity with little Roko in her arms. Havvity’s sweet open face was clouded with fear, but Roko took his thumb from his mouth and grinned.

‘Kawwyy!’ he exclaimed, his version of Kal’s name, and tried to wriggle from his mother’s arms into Kal’s.

‘Not now, Roko love,’ Kal said. ‘In a minute!’

Luja wickered softly and snuffled his nose into the child’s hair.

‘This way. Quickly.’ Havvity pulled Kal and Luja into a stone arch and through groaning stable doors to a small, covered courtyard. She pushed the doors shut just as the Herring mob came round the bend.

Kal and Havvity stood very close with Roko sandwiched between them, eyes locked over the top of the child’s small head. Havvity’s expression softened at last, and her eyes said hello, good to see you. Kal put a finger to Roko’s lips.

‘Shhhh, shhh.’

‘Shhh,’ Roko whispered back, thinking this was a game, until the shouts of the mob grew louder and more frightening, and he buried his face in his mother’s coat.

They all held their breath until, at last, the shouts retreated towards the square. Rain spattered on the roof above them in the sudden quiet.

Roko plugged his mouth with a thumb once more and leant sleepily into his mother’s arms.

‘I’m so glad to see you, Kal!’

‘And I you!’ Kal said.

‘I feared you were dead, Kal, killed with all our kin at East Cove.’ Havvity’s lips trembled. ‘And now today those posters. What’s going on?’

‘I hoped you’d tell me!’ Kal breathed. ‘I left East Cove days ago to go to Talo.’

‘Oh!’ Havvity’s hand went to her mouth in horror. ‘Then you know about the killings?’

Kal nodded. ‘I was there, Havvity. I saw it happen. Two assassins, not Herring folk. Professional killers. But here’s the thing. They had two Herring bodies. They put weapons in their hands and…’

Kal’s voice faltered at the remembered horror, but Havvity didn’t need to hear the rest

‘They wanted to make it look like Herrings did the killing!’ she said.

Kal nodded again. ‘Whoever’s behind all this wants me dead,’ Kal said. ‘Because of what I saw.’

There was a sudden ring of military boots on the cobbles right outside the door. Kal laid a hand on Havvity’s arm, and the two friends froze in alarm. Voices came from the doorway, just audible over the rain that fell on the roof above. Their low whispering told Kal that these speakers didn’t want to be heard. Kal peered through a knothole to see to whom the voices belonged.

Two black-uniformed officers had taken shelter underneath the arch. One was older, with close-cropped, steel-grey hair, the other younger, with a sandy moustache like a pale pencil line above his thin lips. The older had an air of authority.

‘Wretched weather!’ he snarled. ‘Why didn’t you bring an umbrella, Reeven Dopp?’

He spoke in Nordsky, the second language for everyone in Erem. But his companion answered in Rumyc that few outside the port towns understood.

‘Apologies, Commander Lazit.’ The mustachioed man, Reeven Dopp, was all but cringing.

The older man, Lazit, was instantly angry.

‘Speak Nordsky, you fool. We don’t want Rumyc involvement here to be obvious.’

The reply came at once, in Nordsky.

‘Forgive me, Commander.’

‘Just give your report then, while we are stranded here!’ the Commander snapped. Reeven Dopp seemed reluctant to reply. He cleared his throat. Lazit rolled his eyes. ‘Oh, get on with it!’

‘Well, Commander,’ the man began. ‘Our special operatives completed the two missions.’

‘And were the necessary terminations achieved?’

‘The what?’ Reeven Dopp stuttered.

‘Oh, for goodness’ sake, man!’ Lazit growled. ‘Did they kill everyone at Talo Numikalo and East Cove?’

‘Oh, yes.’ Reeven Dopp nodded eagerly. ‘But there was a small problem … a witness at Talo.’

Lazit let out his breath in a hiss.

‘Tell me they didn’t allow this witness to escape?’ Lazit snarled. Reeven Dopp hung his head. ‘I’m afraid so, sir.’

Lazit spoke through clenched teeth. ‘And where are our special operatives now?’

‘On the way to their next assignment, sir.’

Lazit passed a hand over his eyes. ‘You do understand that this civil war is vital to our plans, Reeven Dopp?’

‘Oh yes, of course, Sir.’

‘Then deal with this witness.’ The venom in Lazit’s low whisper almost made Kal gasp. ‘They must be silenced, destroyed, discredited. I don’t care how you do it. The witness must not be allowed to tell what they know.’

Reeven Dopp nodded so hard his head might have come off.

‘I have taken immediate steps. Issued a description of the person and named them as a murderer. I have…’

‘I don’t care. All I want to hear is that the witness is dealt with.’

‘Of course, Commander. Yes, I will do all the…’

Lazit waved a hand in irritation. ‘Just get on with it, you idiot. Now, seeing as the rain has stopped, I will continue to the town hall to address our forces. I have a war to start and a gold mine to dig.’

A moment later both the men had vanished, and their footsteps had receded up the street.

‘A gold mine to dig?’ whispered Havvity.

‘They want the gold that’s under Tamen Haja,’ Kal said. ‘That’s why they want to start a war. So everyone will be too busy fighting to stop them.’

Havvity was pale with shock. ‘It’s going to be terrible. Like that mob and the old man!’ She grabbed at Kal’s sleeve with desperate fingers. ‘You could stop it, Kal. If people know the truth, they’ll stop fighting.’

Kal stared at Havvity.

‘Who’s going to listen to me?’ Kal said. ‘I’ve been a misfit all my life. You heard what that man said. They’ll call me a murderer and they’ll kill me. Who will that save? There’s nothing I can do.’

Havvity’s eyes filled with tears.

‘Couldn’t you try, Kal?’ she said.

‘It’s no use, Havvity,’ Kal said softly. ‘You know it’s not.’

Yes, she did know, of course. Kal was ‘the witch’s child’ to the Herrings, ‘the feckless drunk’s spawn’ to the Horses. Nothing about Kal fitted anywhere and never had. As Kal saw Havvity’s slow sad nod a new fear sprang up.

‘I shouldn’t have come here. Now you and Roko are in danger too!’

Havvity looked so small with Roko now fast asleep inside her coat. Kal wanted so much to protect the two of them, but the best thing to do now was to push them away.

‘Go!’ Kal cried. ‘Go now!’

Havvity’s eyes grew wide. ‘But where will you go, Kal?’

‘Somewhere! I don’t know,’ Kal replied. ‘It doesn’t matter. What matters is that you stay safe. It’s better you don’t know where I am. Kal creaked open the door and began to push Havvity and Roko through it.

‘Wait!’ said Havvity. ‘Wait.’ She rummaged in a pocket, pulled out a crumpled piece of paper and thrust it into Kal’s hands.

‘I kept this for you,’ she said. ‘I thought it was a chance for you go somewhere you wouldn’t be a misfit!’ Havvity smiled, then she turned and clattered down the street towards the café.

Kal looked at Havvity’s piece of paper.

Majak’s Marvellous Circus!

Nordsky’s Finest Circus needs new talent visit our ship at Central Quay show Itmis Majak what you can do.

Kal’s forehead rested against Luja’s. The noble, quiet mind that loved the grass and the wind thrummed just beyond the boundary of bone and blood. Kal longed to see his thoughts!

‘What should we do, Luja? What should we do?’

Luja didn’t answer, but the rain fell again, heavy as glass beads. In minutes Luja’s disguise would wash off and he would match the description on the wanted posters. They’d be found and ‘dealt with’.

Down at the quay, Kal spotted the ship at once, the vessel closest to the end which carried a banner down its side.

MAJAK’S MARVELLOUS CIRCUS

The crew were making her ready to leave. They would have to hurry. The sloping cobbles, wet with rain, were too treacherous for more than a walk, but a narrow strip of muddy grass ran the length of the quayside beside the granite blocks that held the sea at bay. It was just wide enough for Luja to find the easy canter that he loved. In a moment they were alongside the vessel.

The cargo was being stowed and everyone was clearly in a rush to escape the conflict that had suddenly erupted in Erem. In the middle of the foredeck, surrounded by boxes, enormous tent poles and a huge roll of striped canvas, stood a man in a red frock coat and a blue top hat. He was tall and elegant, and even from a distance Kal could see that his face was striking. He seemed young to be the proprietor of a circus. Kal called out in Nordsky.

‘Mr Majak, we wish to try for your circus.’

As the man looked up, the last mooring lines were cast off and the ship began to glide forward, slowly, almost imperceptibly, pulling away from the quay toward the grey waters of the Strait of Swans.

Mr Majak raised his hat in greeting in spite of the rain. ‘You are a little late!’

The ship began to move more quickly and the distance between it and the quay widened. Kal and Luja kept pace with it. The crew laughed and pointed at the rain-soaked horse and rider. Kal and Luja were one creature now, rolling with water that ran like a river over them out of the sky.

‘You do not seem to be giving up,’ the man cried.

‘No,’ Kal replied.

‘What can you do? Cantering is all very well, but really more is required of a circus performer.’ The man shrugged his elegant shoulders.

‘Give us space,’ Kal shouted, ‘and we will show you!’

Just in time, the ship’s crew read the body language of this crazy person and the horse. With cries of alarm, boxes, crates and cages were hastily shoved aside to clear the deck and all stood out of the way.

‘We’re going to jump, Luja,’ Kal whispered, ‘jump for our lives!’

Kal felt the horse’s spirit rise, courageous and desperate in equal measure, wild, joyous and completely at one with Kal’s own. Like a great ‘yes!’ cried out through his whole body, Luja bunched his back legs under him and sprang. The hooves of his front feet rang on the very edge of the quay, striking a shower of sparks from the granite, pushing the ground away as if it meant nothing to him. Below them, in the green waters of the harbour, astonished crabs looked up at the biggest flying creature they had ever seen; above was the swirling cloud.

For a moment they soared, then landed, skidding at speed and threatening to slide clear off the deck and into the harbour. But the sturdy deck hands rushed forward and pushed against the horse’s considerable momentum to bring the fatal slide to a halt. The crew cheered and Mr Majak stepped forward, beaming.

‘Bravo! Bravo, everyone!’

Kal slid from Luja’s back. Stand straight, think bold, a voice inside seemed to say. Kal looked the man in the eye and stood tall.

‘Do we get a job?’

Mr Majak smiled.

‘Yes! Yes indeed, Madam, you do!’ He put out his hand to be shaken.

Madam? Kal hesitated, hand hovering.

‘Madam Numiko at your service, Mr Majak,’ Kal said, bowing slightly from the waist.

‘I am delighted to make your acquaintance. Please call me Itmis! Mr Majak sounds like my father.’ Kal noted that the man’s smile did not light up his eyes. He continued, ‘Do let me introduce our other newest performers: the Acrobat Twins, Spion and Listig. They have just joined our company!’

Two women dressed in identical red jumpsuits, with identical yellow curls popped up from between the piles of boxes. Their faces were like dolls, their eyes were as pale as glass, they smiled and yet looked like something that would bite.

‘We look forward to working with you!’ said the one called Spion, whose face was the sharper of the two.

‘Yes,’ said the other, more round-faced one. ‘We love horses.’

Just then, the rain became fierce and slapped the deck, so Kal didn’t notice the little sidestep Luja took to avoid Listig’s reaching hand.

‘We are getting soaked,’ Itmis exclaimed. ‘We should get under cover. I have just one question, Madam Numiko: why is your horse changing colour?

As Luja shook the water from his coat and, with it, the last of the berry dye, the twin acrobats exclaimed in delight.

‘He really is very striking!’ said Spion.

‘Milk white with dark stars!’ said Listig.

‘Very distinctive indeed,’ Itmis added. A look passed between him and the two acrobats that, although unreadable, sent a shiver up Kal’s spine.

3

Skrimsli

The Elephant’s Eye

The cub’s eyes opened on a blurry world. Things loomed out of it. A snout and a warm tongue, cleaning his face. He gave a short ‘mew’ of protest, but the warm tongue took no notice. A firm paw held him still until he was clean all over.

He slept, and drifted about in warm, milky dreams. When his eyes opened again, another face loomed: pale and round, with dark eyes, furless. It showed its teeth but was friendly. Its paws smoothed the cub’s fur and scratched his ears, so he wriggled with pleasure and purred. A sound came from the face, a ‘huh huh huh’ sound that attached at once to the feelings of warmth and pleasure. When he slipped back to sleep this time, the being behind that face slipped with him. Together, they entered dreams of green where they walked between tall trees beside flowing water.

Long Snout and Round Face were his safety, always there to care for him. Their faces, sounds and smells imprinted on the cub’s mind and made a mould to help shape the sort of creature that he would grow into.

The cub found his paws. When he thought ‘move’, they moved! At first his tail was chasing him, but he found it was himself too. There were smells and noises all around. Curious, he crawled towards them. He grew cold and very tired. A huge rubbery tube came for him. It huffed and snuffed, hot wet breath, then curled around his middle and lifted him off the ground. He mewed with terror, certain he would be eaten by the tube creature.

But he was not eaten, or even harmed, instead he was held level with an eye, nested in wrinkled skin. The cub looked into it and saw a world so much bigger than the one he knew. He stopped his mewing and stared into the eye in wonder.

Long Snout and Round Face came running to his rescue. He was lowered into Round Face’s paws, into warmth and safety. They would protect him always. But he remembered the big world inside the elephant’s eye, and it sang to him in his sleep.