Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

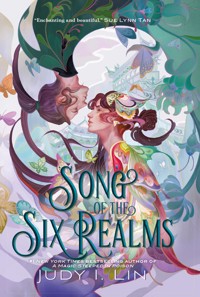

THE INSTANT NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER. Uncover the dark past of the celestials in this melodic tale inspired by Chinese mythology and Daphne du Maurier's Rebecca. Filled with rich imagery and delicate poetry, the Song of the Six Realms will echo long after its tune has ended. Xue, a talented young musician, has no past and probably no future. Orphaned at a young age, her kindly poet uncle arranged for an apprenticeship at one of the most esteemed entertainment houses in the kingdom. When her uncle is killed in a bandit attack, she is devastated to lose her last connection to a life outside her indenture contract. With no family and no patron, Xue faces a lifetime of servitude—until one night, she is unexpectedly called to put on a private performance for the enigmatic Duke Meng. The young man is strangely kind, and surprises Xue with an irresistible offer: Serve as a musician-in-residence at his manor for one year, and he'll set her free of her indenture. When the duke whisks her away to his estate, she discovers he's not just some country noble: He's the Duke of Dreams, one of the divine rulers of the Celestial Realm. The Six Realms are on the brink of disaster, and the duke needs to unlock memories from Xue's past which could help to stop the impending war. But first, Xue must survive being the target of every monster and deity in the Six Realms.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 541

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Also by Judy I. Lin and available from Titan Books

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Prelude

Verse One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Interlude

Verse Two

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Interlude

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Interlude

Verse Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Interlude

Interlude

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Interlude

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Interlude

Verse Four

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

Finale

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

Glossary

About the Author

Also Available from Titan Books

Also by Judy I. Lin and available from Titan Books

A Magic Steeped in Poison

A Venom Dark and Sweet

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Song of the Six Realms

Hardback edition ISBN: 9781835410134

Export paperback edition ISBN: 9781803368788

Waterstones edition ISBN: 9781835411629

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803368795

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SEIOUP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: April 2024

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © Judy I. Lin 2024

First published by Feiwel & Friends, an imprint of Macmillan Publishing Group, LLC. All rights reserved.

Judy I. Lin asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Lydia and Lyra,

the brightest stars in my sky

ԣʆƾ

ON THE STRUCTURE

AND ORDER OF

THE SIX REALMS

The Three Heavenly Stars (of the Celestial and Spirit Realms)

ƖїĐම The Sky Sovereign (The Sun), Ruler of the Celestial and Spirit Realms

ᎠƕĐŶ Supported by the Sky Consort, Xuannu

֊ʾي Guided by the wisdom of the Heavenly Mother of Numinous Radiance, retired to the Crystal Palace of Longevity

First Realm:చThe Celestial Realm

ԣȢɪ Ruled by The Six Rising Stars of the Celestial Court

Ɩί Star of Protection: Trains the Celestial Army to protect and defend the Celestial Realm

Đƭ Star of Fortune: Maintains the Mortal Tapestry, ensuring threads of fate are aligned

ĐȠ Star of Governance: Oversees the minor gods and the selection of tributes from the Spirit Realm

Đࡺ Star of Ordinance: Carries out the decrees of the Sky Sovereign, ensuring the laws of the court are followed

Đඪ Star of Pillars: Maintains the Spirit Tree, ensuring the roots are nourished

Đǜ Star of Balance: Maintains the borders between the realms

Second Realm: 精 The Spirit Realm

Governed by the four major clans. Each clan has their own territories and areas of influence, as well as their own methods of governance. Most Celestials originate from the Spirit Realm.

ɒFlower Clan

ࣁBird Clan

࠳Tree Clan

njWater Clan

Third Realm:ĉThe Mortal Realm

A place of neutrality, Mortal lives are governed by the Celestials, and the afterlife is governed by the Demons in the Ghost Realm. Some Mortals may gain enough spiritual affinity to ascend to the Celestial Realm, usually by passing the Rite of Ascension.

玄炳皇 Currently ruled by the Emperor Xuanbin

The Twin Dark Moons (of the Demon and the Ghost Realms)

Ɩঈ The Moon Sovereign, Ruler of the Demon and the Ghost Realms

魔君 The Demon Lord, Second-in-Command to the Moon Sovereign

Fourth Realm: 魔 The Demon Realm

六魔王 Ruled by the Six Fallen Stars of the Demon Court

ಂళ Prince of Wolves, once the Star of Desire

؎ɟ Prince of Suspicion, once the Star of Movement

ւگ Prince of Sevens, once the Star of Solitude

ۂѓ Prince of War, once the Star of Destruction

Ⴘᑰ Prince of Lies, once the Star of Fear

فݱ Prince of Snakes, once the Star of Pride

Fifth Realm:ލThe Ghost Realm

᪀࠸ Overseen by the Judge of the Ghost Court

Where Mortal souls go after they die in the Mortal Realm. They pass through ten levels of judgment and punishments as deemed appropriate by the Judge before rebirth.

Sixth Realm:ˬThe Barren Realm

All that is known of this place is the Four Planes of Emptiness.

Those who are banished here never leave.

PRELUDE

Once there was a young scholar who was exiled from the imperial court after angering the emperor. He fled to the forest of Sanxia with only his beloved qín and the clothes on his back. He built a small hut out of bamboo and dug a garden for sustenance. Each night he practiced on his qín, for he could not bear to leave the music of his former life behind. He believed his only audience was the wild animals, but one day he glimpsed a woman through the trees. He picked up his qín and chased after her, but she was too quick and he fell, smashing his instrument on the rocks.

The next day he toiled in his garden under the hot sun and, exhausted, threw down his tools. There was no music to look forward to in the evening, and filled with bitter disappointment, he fell asleep under the tóng tree.

He dreamed of a beautiful woman playing the qín, singing in accompaniment with a lovely voice. He woke and saw a nightingale above him on the branches of the tree, but from its mouth came the sound that was like the plucking of the strings. He declared this a sign from the gods and used his ax to chop down the tree. From its trunk, he built two instruments. One he named after the sun, and the other, the moon.

The scholar returned to the capital and became a famous qín maker. His instruments were highly sought after, but he never parted with the originals he built from the tree in Sanxia. Even the emperor came to hear of him and asked him to bring the Sun and the Moon, so that he too could enjoy the pleasing music. But the scholar never arrived at the palace. He had disappeared, along with both of his qíns. Those lovely instruments were never heard from again.

There were rumors he may have been called to the Celestial Realm, reunited with the Nightingale Spirit who led him to the tree. Together, they played for the Celestial Court, and their music flowed through the palace. The Sky Sovereign, pleased with the music, made them both immortal, so they could delight the stars forever.

—“The Bird and the Scholar,” common

folktale of the Kingdom of Qi

VERSE ONE

CHAPTER ONE

I was twelve years old when my contract was purchased by the House of Flowing Water. Its complex was one of the grandest buildings I had ever seen, even among its competitors in Wudan’s most popular entertainment district. The curved, black-tiled roofs were held up by red rafters, and lanterns hung from the corners of each tier, three floors in all. Its name was written in gold calligraphy on an ornately carved plaque that hung over the entrance.

We waited on the street along with others who sought admission, surrounded by their excited chatter. Guards stood watch in front of a barrier of golden rope, preventing anyone from swarming the doors too early. I had to crane my neck to look up the stretch of stairs leading to the main entrance. At the proper time, a bell rang somewhere above our heads, and the double doors were opened to reveal three elegantly dressed women.

They descended the stairs in a splendid procession, and even those who were passing by stopped to admire the marvelous sight. Their hair was artfully arranged upon their heads in sweeping waves, crowned with elaborate headdresses of gold and silver filigree. Jewels dangled from those waves, sparkling as they caught the light. Their robes cascaded down the steps behind them, glittering with embroidered fish. Every part of them was designed to draw the eye, to beckon one closer. What secrets might pass through those lips, curved alluringly in the corners?

“Who are they?” I whispered to Uncle, entranced.

“They are the adepts of the house,” he told me, amused at my awe. “Trained in conversation or music or dance. They are on their way to provide entertainment at a nobleman’s residence or a lady’s garden. One day, Xue’er, you’ll become one of them.” He smiled, eyes crinkling.

The guard lowered the barrier to let them pass, and they swept by us, leaving behind the slightest scent of floral perfume. I stared as the crowd parted for them. They were like the heavenly Celestials in Uncle’s stories who sometimes graced the Mortals with their presence. It was hard to imagine that I, a quiet and awkward child, could ever belong in their midst.

* * *

The owner of the establishment, Madam Wu, was an imposing woman with sharp cheekbones and thin lips. At that time, her favored color was red. I would learn later she changed her surroundings to suit her whims and the fashions currently in favor, so she could always appear like a treasure contained within a jeweled box. To my young eyes, she seemed a phoenix, just landed upon the earth. She was dressed in scarlet, and upon her eyelids there was brushed pink powder in the shape of wings sweeping toward her brows. Her lips were colored a matching shade. But her touch was icy cold.

A thin stream of fear collected at the back of my neck as she lifted my chin with her fingers and turned my head one way and then the other. She opened my mouth and checked that I still had all my teeth. Uncle had told me she was the one I must please in order to gain admittance into the House. The rebellious, angry part of me wanted to jerk away. To behave in a manner that would cause offense so Uncle would be forced to send me back to our cottage on the outskirts of Wudan. The other part of me stayed still under her scrutiny, knowing that to behave in such a manner would be a poor way to repay how he had cared for me the past few years.

Her attention lingered on the scar upon my brow. Most people stared at it—some openly, others trying to avert their gaze, but their curiosity always drew them back. It cut from above my right brow, across the bridge of my nose, ending above my left eye. It used to look even uglier, the skin puckered and red, but had faded slightly in the past year. Still, a scar all the same, and one that could not be hidden by cleverly pinned hair pieces or adornments. It would be a blemish on my record in this place, where beauty was obviously held in the highest regard.

“There is potential for loveliness, without this.” She traced the scar with her fingernail. “What happened?”

“Fell out of a tree,” Uncle said gruffly. “Could have lost an eye, but she was lucky.”

“Hmm.” The mistress continued her consideration of me, unimpressed. “Can she read? Write?”

Uncle made a sound of offense. “She is my niece. Do you think I would neglect her education? Her calligraphy could use some work, but she has read and memorized the ten classics. She can recite three hundred poems from memory. You will not find her knowledge lacking.”

“It takes considerable expense to train an entertainer,” Madam Wu murmured, picking up a strand of my hair and examining it between her fingers. “Usually they come to me at five or six, when they are still malleable and not prone to bad habits. I can have my pick of the young scholars from the monastery or an eager apprentice of the Limen Theater. Why should I choose her?”

My face stung at her words, even though Uncle had warned me it would be like this. A push and a pull, much like the rise and fall of a song. He assured me she would take everything under serious consideration, for she owed him a favor from many years ago. A play he had written for her had gained great repute, and she was even invited to the Eastern Palace to perform. It was with that success she was able to open her own house, growing it to the successful establishment it had become.

This is the way of the world, he had told me, before the carriage came and took us past the frozen lake and into the city proper. What you offer and what someone is willing to give you. Know your worth.

I stood there, trembling, as they joked back and forth, as she criticized every detail of my appearance and mannerisms. Uncle countered with a list of my supposed virtues, but still I was reminded of every one of my faults. If I was so worthy, then why wouldn’t he take me with him while he was called away on his travels? If I had skills to offer, then why was I not suitable to be his companion? But I’d already made my protests, cried my tears, begged him to reconsider. There was no changing his mind. Not when it involved the capital, and the demands of a powerful emperor.

“You say she has an aptitude with the qín.” Madam Wu clapped and a servant appeared almost immediately in the doorway. “Have her demonstrate.”

A table was quickly brought out, the instrument placed upon it, and a stool positioned in front. I ran my hand over the qín and gently plucked the strings, getting accustomed to the feel. It was made of a golden-colored wood, speckled with brown whorls, strung with good-quality silk. Each qín was unique—playing a new one was like meeting a person for the first time. This one’s sound was warmer in tone than my own instrument, but it was well cared for.

“You are her teacher?” Madam Wu poured a cup of tea for my uncle, placing it next to him as they settled upon chairs for the performance. Uncle betrayed nothing in his expression as he lifted the cup to drink, no hint of nervousness or doubt in my abilities.

“Me?” He laughed. “I do not hold my musical skills in such high esteem that I could hope to train someone worthy of your notice. Her skills have long surpassed my abilities. Her instructor for the past two years has been Kong Yang of the Shandong School.”

Teacher Kong. My fingers twitched at the phantom pain that lashed across my knuckles, a reminder of the thin piece of bamboo he held at his back like a sword to use on his students. Arrogant, and fastidious in his devotion to technique, but the sounds that flowed from his hands …

“Kong Yang?” I heard the surprise in her voice. “If she is worthy to be his student, then why not become one of his disciples at the academy?”

“I believe she will receive a more well-rounded education at your house,” Uncle stated, resorting to flattery. “I’ve no doubt once she comes of age, other offers will follow …”

She gave a harsh bark of laughter. “That may work on those who are dazzled by your many accolades, Tang Guanyue, but you and I know each other far too well for that.”

“Of course.” Uncle bowed his head. “There is a reason why not many of my associates are aware of her existence.” Reaching into his robe, he pulled out the stone pendant that identified each of the citizens of the kingdom. One that stated our names, both family and given. My hands faltered and betrayed my nervousness, even as I continued the process of tuning the strings.

Madam Wu held it up to the light, examining the red mark struck across my family’s name. I could see it even from across the room. A stain. Another blemish upon my record. One even more damning than a scar in a house of beautiful things.

“Her family?” she inquired.

“Her father was a minister who was loyal to Prince Yuan,” Uncle said. “I once swore an oath before the Star of Balance that I was blessed to call him my brother, in this lifetime and the lifetimes to come.”

“May he find peace in another life.” She inclined her head, then sighed. “If—and this is only if—I were to admit her into my ranks, there is no guarantee she would ever be pardoned.”

“You would be the one to give her the best chance at success.” Uncle stood and bowed deeply. It hurt me to see him beg, for I knew his pride. The chance of me ever clearing my record was slim, but Uncle wished for me only the best opportunity. I was beginning to understand it now.

“I cannot make any promises.” She stood and helped him up, alarmed at the display of reverence, gesturing for him to sit again. “That a rank such as the yuè-hù should exist in this enlightened time is a disgrace upon us all.”

To hear it uttered felt like a slap to the face. A term that I’d heard followed with spitting on the street, a bitter reminder of what caused the execution of my father, mother, and brother. To have my family name stricken from the Book of Records.

“Guxue.” She looked toward me then. “A fitting name for a poet’s ward.”

Solitary Snow.

It was indeed appropriate for someone who would never marry, never bear children, never have anything to my name. I would exist only to serve, to bear the punishment of the transgressions of my parents, unless the emperor or empress ever found me worthy of a pardon. I willed myself to remain still, even as tears threatened to overwhelm me. To wait, even as my hands shook in my lap.

Madam Wu considered me for a moment, then nodded. “For a student of Kong Yang, I will listen and see.”

That was my cue. One chance to prove that I could be an asset to her establishment. I chose a song called “Morning Rain,” which paid homage to the House of Flowing Water. The sound filled the small room, the notes quivering in the air like dew on a leaf. The song continued, imitating the sound of raindrops falling one by one, splattering on the stones below.

For all of Uncle’s complaints about my calligraphy, my lack of finesse in pleasant conversation, my tendency to stumble when reciting poetry, I knew from the first moment I plucked the string of the qín that this was what I would master. This instrument of scholar-officials, the pinnacle of refinement, revered in stories as the one favored by even the Sky Sovereign himself. The qín was capable of elegance and meditation, or fury and dissent. Its seven strings could express so much in the grasp of a skilled musician.

The last notes trembled in the air before I dared to look over at my audience. Madam Wu had her eyes closed, like she was savoring the sound, a smile upon her lips. Uncle gave me a small nod, and I knew before Madam Wu said anything, she would take me into her house. I would join the ranks of the House of Flowing Water and leave my childhood behind.

CHAPTER TWO

Uncle left not long after I gained admittance to the House, unable to delay a direct summons from the emperor for too long. He promised before he left that he would visit when he could. I managed to hold in my tears while we said our goodbyes and only allowed them to flow when I could no longer see his carriage.

The House of Flowing Water was a city within a city, I learned. It opened midday for a show that was accompanied by refreshments. Soon after, the novices and servants would descend upon the hall, scrubbing furiously to prepare for the evening performances. The shows rotated by day of the week and were renewed each season, for the mistress knew the audience was fickle and constantly clamored for new delights.

The House employed a drum troupe, with dancers to accompany their rhythms with cymbals or scarves. There were two groups that specialized in opera, as well as duos and trios who performed theatrical skits wearing elaborate masks. Many of the performers could also sing and play the pipa or the flute. In order to dazzle the eye with sets and costumes, the House had an on-site group of seamstresses and artists responsible for transforming the many spaces of the establishment to appear otherworldly. One day we could be in the dark and dreary realm of the ghosts, the next in the fanciful realm of Celestials or the colorful Spirit World.

True to his word, Uncle came to visit me when he was able, when his travels brought him back to Wudan. His visits broke up the monotony of the days drifting into weeks, into months, and then years.

Uncle asked the same question, every visit, as he took me strolling through the market streets. He would look at me, and ask softly, “How are you faring in the House, Xue’er? Is the madam treating you well?”

I would respond the same way each time, even though it only contained a half truth: “Everything is fine, Uncle. They are very kind to me.”

I could not say that the inhabitants of the House made me feel unwelcome—I was not shunned or made to feel lesser because of my status. Uncle had promised me that the House of Flowing Water would be a refuge, and it was. The term yuè-hù was banned within those four walls. I was regarded the same as any of the other novices, and told to call the mistress Auntie Wu, as she was referred to by all under her protection.

It wasn’t that I was kept idle either. No, the days were busy and filled with lessons and tasks. My education on etiquette, history, and philosophy continued. I was instructed in the art of serving, and assisted in many of the other novice chores. However, I was not permitted to be in the kitchens, for my hands were deemed too precious to risk injury. As the years passed, I learned how to maneuver among the tables of the packed dining room, carrying large platters of food and drink. I learned how to pour tea and wine without spilling a drop. I could distinguish the roles and ranks of Wudan society, recognizing patrons from the details of their clothing and mannerisms. I knew how deeply to bow and how to cast my eyes down when speaking and being spoken to.

It wasn’t that I was lonely either. I made acquaintance with an apprentice in the drum troupe who treated me almost like a little sister, and she would give me an extra bun with supper or sneak me an occasional sweet. There was another apprentice of opera who loved to listen to me practice, and would join her voice to my instrument in joyous accompaniment. But because of my personal history, hidden away from society in a cottage waiting for my father’s transgressions to fade from the court’s memory, I would often retreat into my books and music. An escape from the overwhelming noise and bustle of the House and the city. And it was because of those books and poems and stories that I felt a restlessness inside of me that grew with each year.

I wished to appear grown-up in Uncle’s eyes, for him to know that I was furthering my education as he wanted. I hoped that one day he would see me as a worthy companion to take along on his travels. There were not many other opportunities afforded to those like me, and like many other children, to be refused something only made me desire it more desperately.

This year, though, marked my seventeenth year, and this summer’s visit would be different from the ones that came before. For it was the year of my Jī Lǐ, the coming-of-age ceremony that all citizens of the kingdom underwent. In this house, it indicated our transition from novice to apprentice, from servant to performer, and Uncle had come to see it.

Auntie had given me a reprieve from my tasks for the little time he was in the city, and those days were among my most treasured memories. Eating red candied fruits on a stick that turned our tongues red. Burning our mouths on the soup that spilled out of the dumplings because of our impatience. A gift of a fan, upon which there were delicate plum blossoms, hand-painted, that I admired in the market.

“Let me tell you of the gossip from the capital,” he said, laughing at my claps of delighted anticipation.

I never knew how much of his tales was embellishment or reality, but I clung to each word all the same. His stories of the princess and her assortment of exotic pets that roamed her private gardens, or the minister who commissioned a series of lewd stone sculptures that scandalized the court. His descriptions of them made me double over, chortling at the imagined sight.

Later, with our bellies full from the crispy duck and bitter greens of the kitchens, we played card games in his private suite at an inn down the road. Our reunions gave me a pleasant and familiar feeling, a reminder of my old life. That once I had a mother and a father and an elder brother, even if they were only vague smears of memory to me: a certain laugh, a strain of music, the scent of rain. Uncle was my connection to them.

Once our games were done, I knew that it was time for the request that came at the end of each of his visits. One that was just like his questions after my well-being. One that I both anticipated and dreaded.

“Show me what you have learned while I have been away,” he instructed, wine in hand, expression serious.

I brought out my qín then, already prepared. I played through the repertoire that I had painstakingly practiced for the weeks leading up to this visit, each piece selected to demonstrate a new song or a particularly challenging technique. He listened intently, foot tapping along with the rhythm.

“Ah,” he sighed afterward when the last strains of the melody were gone. “The qín is the instrument of your soul, of that I have no doubt.”

His approval pleased me, for some part of me was still six years old and frightened at being away from home, and he was the one who made me feel safe.

“But the way you play …” He regarded me with all sincerity then. “It reminds me of ‘The Ode to the Lost City.’ The Poet Zhu’s sadness upon realizing it was impossible to return to his homeland.”

I had thought I was careful about how I portrayed myself, and yet I could not hide from him. My music betrayed my innermost thoughts.

“I only want you to be happy, Xue,” he said softly. “If only—”

“I am,” I interrupted him, wanting to be reassuring. Perhaps if I said it enough times, I would believe it myself.

“I have something to show you.” Uncle stood. He lifted a large box onto the table and gestured for me to open it. “I encountered this during my travels, and thought you might like to see it.”

With the size of the box, I had an idea of what it could contain, but my hand still trembled a little in anticipation. I slid off the lid to find the item wrapped in soft, blue silk. Slowly and reverently, I pulled off the cover to find a lacquered qín. One that gleamed a deep, rich red.

I lifted it out of the box and set it upon the table to examine each and every component. My fingers skimmed over the bridge shaped like a mountain, then to the other side, the dragon’s gums. There were thirteen round pearl inlays, each shimmering with its own milky hue. Underneath, I checked the tuning pegs, as well as the pillar of earth and the pillar of heaven. Everything was as it should be. An instrument beautifully constructed at the hands of a master qín maker. Her artisan mark was etched upon the underside: Su Wei. A revered name in the musicians’ circle. The beauty of it put my own practice qín to shame.

“‘The Bird and the Scholar,’” I whispered, remembering the folktale that was one of Uncle’s favorites.

“Su Wei was thought to be the scholar’s apprentice,” Uncle said with a knowing smile. “There are not many of these left in the world.”

I plucked one of the strings, and the note quivered in the air.

A lump rose in my throat. I was afraid to speak. Afraid of what Uncle would say. I didn’t know how I could bear it if this resplendent thing was only brought here for me to try and then be taken away. I could not believe that Uncle, even with his tendency to tease me, could break my heart in such a way.

I looked up at him, wordless, and he shook his head.

“Do not worry, Xue’er,” he said gently, placing his hand on my arm. “It is yours.”

CHAPTER THREE

The next day I was bathed and powdered, my hair brushed with a hundred strokes and then oiled until it shone. With nimble fingers, Feiyun—my friend with a talent for the opera—pulled the dark strands into an elaborate knot piled high on top of my head, a hairstyle only befitting of a girl when she came of age. Then I was dressed in underclothes of midnight blue edged with gold, the colors in fashion that season. Gauzy fabric of a lighter shade, the pale blue of a cold winter sky, was draped around my shoulders and skirts, pinned into place until it felt as if I were surrounded by a cloud. My closest companions then each kissed me on the cheek, and sent me on my way with their blessings.

I joined the other two novices who were also coming-of-age, both boys, in the hall. Matron Dee, Auntie Wu’s second-in-command, was the one to lead us up the stairs to the altar room, a sacred place usually forbidden to us. The room watched over the main hall like a star, windows open to look upon the space below. It existed as a reminder of the Celestials above, guiding us as we moved through the cycle of birth and rebirth.

We knelt before the altar, the three of us in a line. Above us hung the portrait of the Star of Fortune, the god who looked after our house. He held a book in one hand, a calligraphy brush in the other. His face was stern, for he was responsible for all of our fates—who we were destined to meet, influence, or marry. There were red strings draped over one of his arms, and to his left there was a laughing woman who held up the rest of the threads in her hands, surrounded by birds of all kinds holding the ends of the strings in their beaks. Some called her the Minor Star of Lovers, others, the Guardian of Dreams, for to love and to dream were the sustenance of Mortal existence. To his right was a man strumming a pipa with an expression of pleasant enjoyment. This was the Minor Star of Talent, worshipped by performers, who prayed his light shone upon them so they may gain recognition for their abilities.

This trio of Celestials were our spiritual guides, and so our offering table was well stocked. There were fresh-cut branches of wintersweet and sprigs of narcissus blooms. In the center of the table lay a plate of peaches, their ripe scent mingling with the incense, for these were the fruits most beloved by the gods. Beside them was a platter of pastries to sweeten their palates so that they may look upon us kindly. The third dish held an assortment of nuts so that they would enjoy each morsel, and never leave us and take away their blessings.

We waited in quiet reflection until the doors opened again, admitting Auntie Wu. To my surprise, Uncle was there beside her as well. He retreated to the side of the room to observe, and the ceremony began. For each of us, Auntie conducted the same steps of the ritual as we knelt. She sprinkled water in front of us, then burned a paper talisman of protection in a metal bowl. She walked around us so that the smoke encircled our bodies. Matron Dee recited the chants that heralded our coming-of-age.

For the two other novices, since they were boys becoming men, Auntie Wu draped black cloaks around their shoulders and placed black caps upon their heads. As she approached me, I looked down at her embroidered slippers, giving her the respect deserved of an elder.

Auntie spoke the words above my head: “At this time, presented before the gods, you are acknowledged.” She slid the pin into my hair, where it snagged sharply. A pinch of pain, and then I was a woman. No longer a girl.

I thought the ceremony concluded, but she stepped aside, and a shadow passed over me.

“As your father acknowledged me as brother, so I acknowledge you in turn,” Uncle’s voice rumbled above me. I felt the envious gaze of the others, for they had no family to attend to them. There was a small spark of pride inside of me as I bowed my head before him.

“Thank you, Uncle,” I whispered as he draped the cloak around my shoulders. I would no longer wear the short cape of children—instead I would have a full cloak that brushed against my legs as I rose to standing. Fur tickled the back of my neck. There was a weight to the cloak as I turned, the hem trailing along the floor. I would grow into it. My fingers touched the material. It was soft, smooth, luxurious. The embroidered design along the edge was of flowers, orchids done in silver thread.

We bowed to the gods first, then to the mistress of the house who had taken us in. We were now apprentices, capable of performing for our esteemed patrons if Auntie deemed us worthy. A servant placed a cup of wine into my hand, and the mood turned from serious to cheerful. The air filled with words of congratulations. The wine burned its way down my throat.

Uncle embraced me, his eyes shining with pride. In that moment, I felt blessed with his precious gifts. Seen, recognized, and loved.

* * *

I said goodbye to my uncle the next day, and he promised me he would return before the snow fell. I spent the next few months eagerly learning the nuances of my new qín, drawing out its unique sounds. I found myself wanting to prove that I was worthy of such a priceless instrument.

The next time Auntie called me to her study, it was at the beginning of autumn. I was certain it was finally my time to take on the apprentice role, for which I had grown impatient.

I entered the room after a quick tap of my knuckles upon the wooden door. Auntie sat at her desk, looking down at papers in her hand.

“Ah, Xue …,” she said, but it was more like a sigh. She lifted her hand and waved me closer.

I took a step forward, but she finally looked at me, and I saw her eyes were misty with tears. I had never before seen her lose her composure. It was the equivalent of a scream.

“A letter came from the capital, bearing sorrowful news,” she said, voice quivering. “Your uncle’s caravan was attacked by bandits on the way to Wudan. He died two weeks ago.”

My knees almost gave way. If it weren’t for the table beside me, I would have ended up on the floor.

“The House will take care of you, child. You’ll still have a place here,” Auntie said, in an attempt to be reassuring.

I must have said something to her afterward, or perhaps not. My memory of that afternoon was obscured whenever I attempted to look back, like the fog that would sweep over the lake unexpectedly when the winds shifted.

In a way, nothing had changed, and yet, everything had changed. I belonged fully to the House of Flowing Water now, bound in servitude until my death. It was time to set aside the foolish, secret dreams I had of traveling the world like my uncle and the wanderers in his stories.

I would respect his memory, and try to be happy.

* * *

The routine of the House saved me from disappearing into my sadness. New responsibilities awaited me as an apprentice. I was like a puppet being led along by the strings, performing the steps I knew so well with a hollow heart. For the afternoon banquet, I played behind a screen while the guests enjoyed a performance from our limber acrobats. In the evening, I was the music that trickled down from the rafters above, hidden from view, while patrons feasted.

The House of Flowing Water continued to entertain guests of high standing in society, and Auntie honed our reputations as a house capable of putting on grand shows just as well as intimate gatherings. She purchased the adjacent building, expanding the House into the inn business, with rooms made available for visitors who wanted to stay overnight.

The pain of losing my uncle became a quiet hurt, one that struck me unexpectedly whenever I read a passage that reminded me of his wit, or I thought I had caught his voice somewhere in the distance.

Though I’d been plagued by bad dreams ever since I was little, a new nightmare emerged: Me, searching for him in a crowd. Catching a glimpse of his face, and then losing him in the distance. Pushing past the sea of bodies that kept getting in my way, being swept back, again and again.

Xue! There’s something I have to tell you! he would call to me. Then I would wake up, his voice still echoing inside of my ears and a brittle sense of loss inside my chest.

I devoted myself to the practice of the qín, spending most of my time in pursuit of the clarity of sound, the perfect technique and form. I cared for Uncle’s gift until I knew it as well as my own body, its dips and crevices, the unique markings upon the wood.

I moved into the newly constructed women’s quarters once they were completed, finally joining Feiyun and my older companions. The apprentices spoke of flirtations and secret notes and gifts from patrons. Late night whispers when someone tiptoed in, a little tipsy from one of the many parties hosted by Wudan’s literati. I watched as a few of them rose to the ranks of adept, butterflies among a field of flowers, gaining their share of devotees. Some of them fought one another in subtle jabs, sharp words or spilled paint, as strong personalities often clashed when they vied for the attention of a wealthy or esteemed guest. But most of them were never rude to me, even though they all knew my status as an Undesirable.

Perhaps it was out of pity. I knew that their chances to gain their freedom was a dream that hovered before them, a hopeful future soon within reach. If they earned enough to pay off their contract or caught the attention of either a devoted patron or an amorous suitor. Not like me, bound to the House until my death. Some of them distanced themselves from me, as if my social status was a condition that could be caught like a disease. Others tried to encourage me by using me as a willing canvas for their experiments with new shades of makeup, and they told me rumors of exiles who had found their way back into society and reclaimed their names.

They would often speak of Consort Yu, a favored concubine of the Xuanwu emperor with a notorious past. She was once a pipa musician whose yuè-hù status was struck from record when he became entranced with her beauty and brought her to the inner palace. The gossip raged through the kingdom when her past was discovered, and I found it laughable that they believed it could also one day be my fate. It would be just as likely for the Heavenly Mother of Radiance to bestow the title of Blessed upon me and lift me up among the stars to become one of the Dancing Maidens.

Some of them thought me shy, resigned to my fate, and therefore hesitant to participate in casual flirtations. But it wasn’t that. I just never felt that tug they experienced when they found someone pleasing to the eyes. That fluttering in my belly eluded me, and never the sharp pull of the heartstrings that said the Minor Star of Lovers was attentive to my future. In this way, I drifted. Accepted, of sorts. Peered at the rest of the world from behind screens and doors. Watched as the guests laughed and feasted and enjoyed themselves. Waited nervously for the day when it would be my turn on the stage.

The restless feeling returned eventually. I should have been grateful, for the clothes on my back and the roof over my head, and yet I still felt that something was missing. It was not the warmth of a lover’s touch or the call of freedom, just the knowledge that this was not where I was meant to be.

Even though I was surrounded by people, I could deeply relate to the words of one of my favorite poets, another concubine of a former emperor, trapped within the beautiful walls of the inner palace: I am surrounded by many splendors, and yet I am alone.

CHAPTER FOUR

It was the first snowfall of the year. Cries of delight filled the room as the windows were thrown open, letting the cold air in. A few of the apprentices yelped, but others laughed. Someone would, inevitably, make a joke about my name, as they did each year. We could look forward to the desserts made with warming ingredients, many hot cups of ginger tea, and red bean soup.

Serendipitously, the first snowfall coincided with the first day of the Little Snow on the solar calendar, which meant the House of Flowing Water was closed to guests for the afternoon. We spent the day preparing the house for the change in seasons: replaced the incense for a spicier fragrance that warmed the blood and invigorated the mind, pulled our winter clothes from our trunks, and aired out the heavier coverings that would keep us warm in the evening’s chill.

We endeavored to keep our guests as comfortable as possible, and it took a considerable amount of fuel to keep such a large building heated. I swept the dried leaves from the garden paths, walking past the piles of chopped wood that were stacked against the side of the shed. The sun hung low in the sky and shone with weak, wavering light through the thin clouds. The air was still, expectant. As if all the birds and creatures knew the true beast of winter lurked around the corner, waiting to pounce.

That night was a significant evening for me, because Auntie Wu had finally selected me to perform in the main hall. Matron Dee had announced it at dinner the night before, and I was offered many congratulations by the other apprentices. The women’s quarters were a flurry of activity when I returned to dress for the evening performance. There were fabrics, ties, and shoes strewn about everywhere. Open containers of cosmetics on dressing tables and hairpins that sparkled in the light. There was an atmosphere of merriment, interspersed with occasional bursts of laughter and giggles as jokes were made at one another’s expense. We did not have to maintain our careful composure in here, for no one was watching to ensure we kept our decorum.

I slipped into a long, light green skirt with many folds. It was designed to drape gracefully over the stool that I would sit on. My jacket and sleeves were tight to the body, almost constricting, in order to not impede the playing of the qín. I looked enviously at the outfits of the dancers, with their shorter skirts and flowing sleeves.

The dance troupe was a colorful sight to behold. They each had a red blossom painted upon their foreheads, and their eyes were outlined in a dark, dramatic fashion. Their hair was pinned up in two loops, then bound with festive ribbons that trailed down the sides of their faces and brushed their shoulders. They wore red sashes wound around their chests that matched the embroidered edges of their skirts.

Auntie strode into the chamber, clapping her hands to capture our attention.

“We shall put on a good show tonight, my lovelies,” she declared, for in speaking of things, she believed she would make them real. “Fortunes’ blessings upon our house.”

“Fortunes’ blessings,” all of us echoed in turn. The portrait of the Star of Fortune flashed in my mind. He was said to weave all of our Mortal fates upon the Tapestry of Destinies, and a part of me always found the thought uncomfortable. Did our choices mean nothing when our fates were already knotted, predetermined before we even left our mothers’ wombs? I took a deep breath and tried to brush away the thought. I could not let myself be distracted tonight.

The evening’s festivities began, and the hall was filled to capacity. A typical sight upon the changeover of a season, as many were always eager to see the new performances, but it did nothing to ease my jagged nerves. I stood in the back, behind the carved wooden screens that blocked off a section of the hall and allowed performers to enter unobtrusively.

The first performance of the evening was an opera. A flute trilled in the background as two figures crossed the stage, footsteps light. I recognized Feiyun’s voice immediately, even from behind her mask.

Our shoulders brush

A moment frozen in clarity

I recognize you

See myself in your gaze

Another woman’s voice, low and husky, joined her in the duet as they both bowed to one another, then to the audience, who represented the gods they hoped would bless their union. They made quite a striking pair, dressed in wedding colors of red and gold. It was a love song, one called “Heaven and Earth,” about a Fox Spirit who accidentally fell into the Mortal Realm—characterized by Feiyun’s mask of white, red, and black—and the huntress who saved her from the fearful villagers. Even though their love was forbidden, they still married and performed the rites before heaven, committing themselves to each other. The Sky Consort herself took pity upon the lovers, and lifted them to the Celestial Realm, so they could be together for eternity.

Spirits were associated with nature, flighty and wild. Beings who absorbed enough of the cosmic energy to gain sentience, able to take on human appearance if they wished. I loved stories about them. Birds who became warriors. Fish that spoke in riddles. Stories that helped me traverse other realms. Focusing on the beauty of the words and the melody, I was able to breathe a little easier.

Then it was my turn to ascend the steps, my qín held against my heart. The room was filled with so many people, and yet all of their faces were a blur.

I sat on the stool and arranged my skirts around me, like the adepts had instructed. With my head down, I could pretend the screen was still there, separating me from the rest of the room. There was only the safety of the stage, and the performers I was to accompany. The two dancers glided forward and took their positions. One was dressed as a king of dynasties past, the other his devoted concubine.

“The Tragedy of Consort Xiang” was a sad story, as shown by the way the sound poured from the strings. No vocalist accompanied our performance, but it was the dramatic dancing of the figures on the stage that told the tale.

Swirling flowers, falling leaves, mark the days I’ve dreamed of my king but have not seen him

The pain inside like my organs severing, my tears leave ever-deepeningscars …

I lost myself in the expression of the music, careful to ensure each note wept. My qín sang with an ache that manifested the concubine’s longing. The king and his concubine danced around each other, always just out of reach, as the lament wove its way around them. The consort sank to her knees in despair as she realized the wind carried the king away from her. He was only a dream, a figment of her imagination.

When the last notes crept in, like the wind that swept through the bamboo grove where the concubine perished, I wondered what that all-consuming, gut-wrenching love would feel like. If there was such an emotion that would render me unable to live, I wasn’t sure the gaining of it was worth the loss.

I joined the other performers to bow to the sound of enthusiastic applause. When I glanced up at the audience, some of them dabbed at their eyes or noses with their handkerchiefs, visibly emotional. I felt a little spark of hesitant pride in my chest. I had done my part through the power of the song. It was everything I thought it would be, what I had longed for: to be seen, to be acknowledged. Even though I was more familiar with poets of old than real people, even though I was not meant for love or a family of my own, I could pretend for a moment that I was one of them.

Once I was safely alone in the back hallway, I wept.

I knew my uncle would have wanted to be here. He would have sat in the best seat in the house.

* * *

I hid in the shadow of the stairwell for a while longer, my face still hot from the excitement of my first mainstage performance. Closing my eyes, I took in the sounds of the house, like listening to an old friend. The clatter of the dishes being cleaned in the kitchens, the drums of the next performance shaking the floor beneath my feet.

Down the hall there was a thump, and then a soft cry. I wiped my eyes with my sleeve as I stood, setting my qín aside, and crept toward the source of the sound. It came from the hallway that led to the gardens, where the kitchen staff would bring out food for the outdoor banquets. I wondered if one of the servants had slipped and fallen, but to my shock I saw the back of a man in black robes. Not one of our staff, not with his top knot and the pendant he wore at his side. A patron, where he shouldn’t be.

He shifted. A flash of red caught my eye, then a terrified, pale face turned in my direction. It was one of the dancers, her mouth covered by his hand. He struggled to keep her pinned against the wall. She saw me and then thrashed harder, cries muffled. He turned then and met my eyes. His lips pulled back in an imitation of a smile.

“I am the second son of Minister Jiang.” He leered in my direction. “Scurry away, little one, and you’ll find a fat purse sent to you tomorrow for your trouble.”

I scowled. Some of these patrons sauntered in here as if they owned the establishment because they flung about a bit of coin. They believed our worth was measured by our price, and our only value was to do their bidding. All of us could tell stories about being pinched and grabbed by overeager guests. Those who ordered us about like servants of their own household. Gossip, too, was shared about other houses, owners who were less scrupulous with the rules, even though there were regulations and licenses that governed the entertainment and pleasure districts.

“Get away from her.” I stepped forward. Out of everyone in the house, I had the least to lose from the confrontation of a minister’s son. I was already an outcast from society, so what else could he possibly do to me?

He pulled the dancer to his side, twisting her arm behind her until she yelped in pain.

“Who are you?” he snarled. “How dare you speak to me in that manner!”

“I think you would do well to remember what sort of establishment this is,” I said, trying to make myself appear as threatening as possible. “I saw Magistrate Qiu and Official Au in the audience tonight—if I scream and they come, I wonder whose innocence they will believe?”

“You … you wouldn’t dare!” he sputtered.

I drew in a deep breath, but then a hand clamped down upon my wrist before I could scream. I looked up to see the impassive face of Matron Dee.

“Jiang Erlang,” she said, stepping forward. “Please, let me pour you a head-cleansing tonic. I fear you’ve had a bit too much to drink.”

“Old hag,” he spat in her direction. “I am a customer. You exist to serve me, and I want this little morsel to myself. You want me to hire a private room? How much? I’ll pay it!”

“We are not that sort of establishment!” Matron’s voice was as sharp as a lash. Somehow she had procured a rod in her hand, and she advanced menacingly. “Go seek the pleasure houses.”

Jiang Erlang’s eyes darted to the weapon, then back up to the older woman’s face to judge her seriousness. He cursed her ancestors under his breath and pushed the girl forward. She stumbled, falling to her knees, and he fled out the back door.

“H-he grabbed m-me.” I finally recognized the girl as Anjing, one of the newer dancer-apprentices. Tears streaked her face. “I swear, Matron, I didn’t—”

The rules of the House of Flowing Water were clear. There were legal distinctions between the types of houses and the kind of entertainment that could be provided within. To break those rules would subject the House to fines and the loss of its operating licenses, especially as many of its patrons were magistrates and officials. We received constant reminders to conduct ourselves accordingly.

“It’s all right, Anjing,” Matron said soothingly, bending down to help her.

I took that as my cue to leave, but then Matron Dee turned to me. “You’re wanted by Madam in her office, Guxue. Immediately.”

“Did … she say why?” I asked, more afraid of this sudden meeting than of that pathetic nobleman.

“You know she does not like to be kept waiting,” Matron said, a note of warning in her voice.

Anjing mouthed Thank you behind her, and I gave her a quick nod before hurrying away.

CHAPTER FIVE

I rescued my qín from where I’d hidden it beside the stairwell and ascended, dread mounting with each step. I thought I had done well for my first performance, but there would only be one listener whose opinion mattered.

Madam Wu sipped tea at her desk, ledgers spread out before her. The beads of her abacus clicked rapidly under her fingers. While I stood there waiting, I distracted myself from my nervousness by admiring her treasures: embroidered wall scrolls depicting birds and flowers, a collection of small painted vases set in custom-built niches in the wall, a gilded bird cage in the corner where her parrot lived.

I fidgeted while she completed her calculations, reminded of how I had not even dared to lift my head when I first walked into this room. I recalled the intensity of her gaze, and I still withered under the same scrutiny when she finally acknowledged me.

I felt twelve years old again. Awkward and unsure.

Auntie stood, her appearance impeccable as always. She wore a green silk jacket with full sleeves and an undertunic of peach. Her skirt was of a paler green, a shade reminiscent of the highest quality of milk jade. But most splendid of all was the necklace she wore: a collar of thin gold filaments, upon which flowers with ruby petals and gold centers dangled. On another woman the necklace would have appeared gaudy, but it suited her.

“You’ve done well for yourself, Apprentice Xue,” she said to me with a smile. It caused that tight knot inside of me to ease ever so slightly. A smile was a good sign, that it was possible she was pleased with me. She gestured then for me to sit down in one of the chairs under the painting of the Qinling Mountains.

I gingerly perched myself upon the chair as directed. She sat down opposite me, and immediately there was a servant behind us to pour tea into the already prepared cups between us.

“Your first public performance. No screen to hide behind any longer. How did it feel?” she asked. I felt as if I was being tested, and I did not like to be the sole recipient of her attention. It seemed to me like the threat of a very sharp knife.

I decided to be honest. “I was nervous, Auntie. But I believe I made only minimal mistakes.” My palms began to sweat then, but I did not want to rest them on the finely carved arms of the chair. I furtively tried to wipe them on my skirts, then decided to sit on them instead, to resist the temptation to fidget further.

“Did you speak with anyone when you entered the hall, or when you were leaving it? Did you speak to anyone at all, anyone who is not currently under the employ of the House?” The questions came, one after the other, and the dread seeped back. How did she find out about what happened with the minister’s son and Anjing so quickly? Perhaps the rumors really were true, that Auntie was actually a Tiger Spirit hiding out in the human world. It was why she appeared to never age, and why she could hear and sense the goings-on in any corner of her domain.

“Think,” she urged.

“I … I spoke with Minister Jiang’s son, briefly,” I said. Threatened him, more like. But hopefully Matron Dee would explain it under a kinder light.