10,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Eland Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

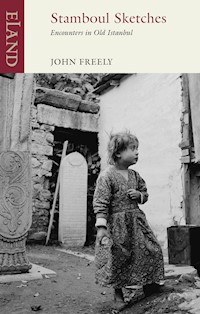

Throughout the 1960s, John Freely explored the alleys, hidden corners and monuments of Istanbul, in between teaching, to create a legendary guidebook with Hilary Sumner-Boyd. But all the passages that were too personal, too capricious, too idiosyncratic, too indulgent of eccentric personalities, too wrapped up in the love of mid-afternoon banter, too indulgent of musicians, dancers, gypsies, dervishes, drunks, beggars, fishermen, poets, fortune-tellers, folk-healers, mimics and prostitutes, were cut from their scholarly guide. Stamboul Sketches is fashioned from these off-cuts, a chronicle of chance encounters inspired by Evliya Çelebi, the Pepys of seventeenth-century Istanbul. It is a beautiful, quirky portrait of a city, which, Freely says, 'grabs you by the heart and never lets you go'.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Stamboul Sketches

JOHN FREELY

with photographs by SEDAT PAKAY and an afterword by MAUREEN FREELY

For Toots

Contents

Introduction

‘Though so many countries and cities have been minutely described by geographers and historians yet this my residence of Constantinople remains undescribed.’ So said Sultan Murat IV to an assembly of scholars in the year 1638, as quoted by the contemporary Turkish traveller Evliya Efendi. This imperial complaint eventually led Evliya to write his own account of life in Istanbul during Murat’s reign and those of his immediate successors. Evliya’s description of the city is contained in two volumes of his Seyahatname, or Narrative of Travels, which he completed in about 1680. Many books have been written about Istanbul since then, but nothing which is comparable to Evliya’s narrative, which recreates the colourful spectacle of life in the capital of the Ottoman Empire in the closing years of its golden age.

For Evliya was superbly equipped and situated to be the chronicler of that most fascinating period in the city’s history. He was in his time a soldier, sailor, diplomat, historian, müezzin, goldsmith, writer, poet, singer, musician, and, above all, a traveller; equally at home in throne-room or taverna; an intimate of sultans and mighty pashas; a friend of poets, divines and sainted idiots; a comrade of common soldiers and humble workmen; familiar with all the exotic avenues and arcane byways of Istanbul life; his keen eye always looking for the curious sight, the odd character, the pleasurable walk or the panoramic view; his musician’s ear listening for the sound of a street-hawker’s cry, the melodies of a dervish song, the ditty of a drunken sailor; his gourmet’s taste seeking out the most delicious food in town, and, although he claimed to be abstemious, the finest wines; his sharp nose sniffing out the earthy odours of Istanbul trade and commerce. Thereby he became a peripatetic encyclopaedia of the street-lore and folk history of his beloved city. Much has happened here in the past three centuries, but when we compare contemporary Istanbul with Evliya’s town we see that its basic character has not really changed. Although the eunuchs and the Janissaries have gone, the sights and sounds and smells in the streets of Istanbul are much the same as those which Evliya records in the Seyahatname.

My own book is an attempt to evoke the spirit of the Istanbul that I have known, just as Evliya did for the city of his day. I have tried to do this through a series of brief sketches of Stamboul scenes. (I have here used the old-fashioned name of the city, as seeming more appropriate for the atmosphere I have tried to create.) Evliya Efendi appears and reappears throughout these sketches, for in his Seyahatname he touches on virtually every aspect of the city’s life. So in my own wanderings through Stamboul I have constantly had him by my side, he comparing his town with mine, like an eccentric companion-guide. And I have often interwoven my narrative with that of Evliya Efendi, trying to bridge the gulf of years that separates his time from ours, so as to reveal something of the continuity of human experience which seems to exist in this ancient city.

These sketches were written over the course of the dozen years during which we have lived in Stamboul, and so many of them may now seem somewhat dated. For the scene has changed, and many of the characters have departed, some never to return. You will search in vain for the Albanian Flower-Pedlar and the Grandfather of Cats; Nazmi’s Café and the Taverna Boem have closed their doors for ever; and some of our street-poets and wandering minstrels now sing and play here no more. Nevertheless I have made no attempt to update the sketches, for they and the photos by Sedat Pakay are a picture of the city we knew and loved in years past, the old Stamboul of our memories.

I would like to express my appreciation to William Edmonds of Redhouse Press for his help and encouragement in putting together Stamboul Sketches. Thanks are also due to Michael Cain for editorial work, and to Alan and Sue Ovenden, and Sara Rau for many helpful suggestions.

J. F., ISTANBUL, NOVEMBER 1ST 1973

Child standing in front of the Byzantine city walls

1

Evliya’s Dream

Evliya, the son of Dervish Mehmet, was born in Stamboul on the tenth of Muharrem in the year after the Hegira 1020 (AD1611) in the reign of Ahmet I. As Evliya writes in the Seyahatname, in the section entitled Anecdotes of the Youth of the Author, ‘At the time when my mother was lying in with me, the humble Evliya, no fewer than seventy holy men were assembled at our house. At my birth the sheikh of the Mevlevi dervishes took me into his arms, threw me into the air, and catching me again, said, “May this boy be exalted in life!”’ After relating other anecdotes concerning these scholars and divines and the comments they made at the time of his birth, Evliya concludes with this characteristic statement: ‘The short subject of this long discussion is to show that I, the humble Evliya, was favoured with the particular attention of these saints and holy men.’

Evliya came from an old and distinguished Turkish family which traced its lineage back to Sheikh Ahmet Yesov, who was the teacher of Hadji Bekta, the founder of the Bektaşi order of dervishes. Evliya’s father had been Standard-Bearer in the army of Süleyman the Magnificent, and was at the Sultan’s side when he died at the siege of Sziget in 1566. During the reign of Ahmet I, Dervish Mehmet became Chief of the Goldsmiths, a trade to which Evliya was apprenticed when he was a young man. His uncle and patron, Melek Ahmet Paşa, was a Grand Vezir in the reign of Murat IV (1623–40) and Evliya accompanied him on many of his missions and campaigns. His grandfather, Yavuz Ersinan, was Standard-Bearer in the army of Sultan Mehmet II and was present when Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453. (Those two generations of Evliya’s family span at least two centuries; either his forebears were incredibly long-lived or the intervening ancestors were foreshortened in the telescope of Evliya’s imagination.)

After the Conquest, Yavuz Ersinan was allotted a plot of land in Unkapanı (the Flour Store), the district around the Stamboul shore of the present-day Atatürk Bridge. The mosque which he founded at that time, about 1455, is still standing and in use; it is probably the oldest surviving mosque in the city. It is called Sağrıcılar Camii, the Mosque of the Leather-Workers, after the artisans who have practised their trade in that neighbourhood for centuries. When Yavuz Ersinan died he was buried in the garden behind his mosque, and his moss-covered tombstone can still be seen there today. But the family homestead in which Evliya was born has vanished without a trace.

When he was six years old Evliya was enrolled in the school of Hamid Efendi in the section called Fil Yokuşu, the Path of the Elephant. (The street from which this section takes its name is still in existence, winding up from the shore of the Golden Horn to the heights above Unkapanı.) Evliya studied in Hamid Efendi’s school for seven years, during which his tutor was Evliya Mehmet Efendi, Chief Imam in the court of Sultan Murat IV. While there he studied calligraphy, music, grammar and the Koran, in the reading and singing of which he particularly excelled. After leaving Hamid Efendi’s school Evliya continued his studies with Evliya Mehmet Efendi, who appears to have given him a remarkably broad education. As Evliya once remarked to Murat IV: ‘I am versed in seventy-two sciences; does your majesty wish to hear something of Persian, Arabic, Syriac, Greek or Turkish? Something of the different tunes of music, or poetry in various measures?’ To which the Sultan replied: ‘What a boasting fellow this is! Is he a Revani (a prattler), and is this all nonsense, or is he capable of performing all that he says?’ We have only Evliya’s own testimony to prove that he was no idle boaster, but an imaginative elaborator of the truth.

When Evliya was about twenty years old, so he tells us, he began making excursions in the vicinity of Istanbul and thereby decided to become a traveller. ‘It was in the time of the illustrious reign of Murat IV that I began to think of extensive travels, in order to escape from the power of my father, mother and brethren. Forming a design of travelling over the whole earth, I entreated God to give me health for my body and faith for my soul. I sought the conversations of dervishes, and when I heard a description of the seven climates and of the four quarters of the earth, I became still more anxious to see the world, to visit the Holy Land, Cairo, Damascus, Mecca and Medina, and to prostrate myself on the purified soil of the places where the Prophet, the glory of all creatures, was born and died.’

With that hope Evliya prayed for divine guidance, a request which was eventually granted to him on his twenty-first birthday. He writes of how he fell asleep that night in his father’s house and dreamt that he was in the nearby mosque of Ahi Çelebi. No sooner had he arrived there, in his dream, than the doors of the mosque opened and a brilliant crowd entered, all saying the morning prayer. Evliya tells us that he was lost in astonishment at the sight of this colourful assembly and that he looked upon his neighbour and said: ‘May I ask, my lord, who you are, and what is your illustrious name?’ His neighbour answered and said that he was Sa’d Vakkas, one of the ten evangelists and the patron of archers. Evliya kissed the hand of Sa’d Vakkas and asked further: ‘Who are the refulgent multitude on my right hand?’ ‘They are all blessed saints and pure souls, the spirits of the followers of the Prophet,’ answered Sa’d Vakkas, and then told Evliya that the Prophet himself, along with his grandsons Hasan and Hüseyin, were expected in the mosque at any moment to perform the morning service. No sooner had Sa’d Vakkas said this than flashes of lightning burst from the doors of the mosque and the room filled with a crowd of saints and martyrs. ‘It was the Prophet!’ Evliya writes, ‘overshadowed by his green banner, covered by his green veil, carrying his staff in his right hand, his sword girt on his thigh, with the Imam Hasan on his right side and the Imam Hüseyin on his left. As he placed his right foot on the threshold he cried out, “Bismillah!” and throwing off his veil, said, “Health unto thee, O my people!” The whole assembly answered: “Unto thee be health, O prophet of God, Lord of the Nations!”’ Evliya tells us that he trembled in every limb, but still he was able to give a detailed description of the Prophet’s appearance, saying that it agreed exactly with that given in the Hallyehi Khakani: ‘The veil on his face was a white shawl and his turban was formed of a white sash with twelve folds; his mantle was of camel’s hair inclining to yellow; on his neck he wore a yellow woollen shawl. His boots were yellow and in his turban was stuck a toothpick.’

Evliya then tells us that the Prophet advanced to the mihrab of the mosque, struck his knees with his right hand, and commanded Evliya to take the lead in saying the morning prayers. Evliya did so and the Prophet followed by reciting the Fatihah, the first chapter of the Koran, along with other verses. After other prayers were pronounced by Evliya and Belal, the first müezzin of Islam, the morning prayers were concluded. ‘The service was closed with a general cry of “Allah!” which very nearly woke me from my sleep,’ Evliya writes. He then goes on to tell of how Sa’d Vakkas took him by the hand and escorted him into the Prophet’s presence, saying, ‘Thy loving and faithful servant Evliya entreats thy intercession.’ Evliya, weeping in his excitement and confusion, kissed the Prophet’s hands and received his blessings, along with the assurance that his desire to travel would be fulfilled. The Prophet then repeated the Fatihah, followed by all of his sainted companions, after which Evliya went round and kissed their hands, receiving from each his blessings. ‘Their hands were perfumed with musk, ambergris, spikenard, sweet-basil, violets and carnations; but that of the Prophet himself smelt of nothing but saffron and roses, felt when touched as if it had no bones, and was as soft as cotton. The hands of the other prophets had the odour of quinces, that of Abu Bekr had the fragrance of lemons, Omar’s smelt like ambergris, Osman’s like violets, Ali’s like jasmine, Hasan’s like carnations, and Hüseyin’s like white roses … Then the Prophet himself pronounced the parting salutation from the mihrab, after which he advanced towards the door and the whole illustrious assembly, giving me various greetings and blessings, went out of the mosque.’

The last to leave was Sa’d Vakkas, who took the quiver from his belt and gave it to Evliya, saying, ‘Go, be victorious with thy bow and arrow; be in God’s keeping, and receive from me the good tidings that thou shalt visit the tombs of all the prophets and holy men whose hands thou hast now kissed. Thou shalt travel through the whole world and be a marvel among men.’ Then Sa’d Vakkas kissed Evliya’s hand and departed from the mosque, leaving Evliya alone at the end of his dream.

Children playing in Sülemaniye Street

‘When I awoke,’ writes Evliya, ‘I was in great doubt whether what I had seen was a dream or reality, and I enjoyed for some time the beatific contemplations which filled my soul. Having afterwards performed my ablutions and offered up the morning prayer, I crossed over from Constantinople to the suburb of Kasımpaşa and consulted the interpreter of dreams, İbrahim Efendi, about my vision. From him I received the comfortable news that I would become a great traveller, and after making my way through the world, with the intercession of the Prophet, would close my career by being admitted into Paradise. I then retired to my humble abode, applied myself to the study of history, and began a description of my birthplace, Istanbul, that envy of kings, the celestial haven and stronghold of Macedonia.’

And so Evliya began the travels which eventually took him all over the Ottoman Empire, which at that time extended from central Persia to Gibraltar and from southern Egypt to the frontiers of Russia. He also accompanied the Turkish Embassy to Vienna in 1664, after which he travelled widely in northern and western Europe, returning by way of Poland and the Crimea. He took part in many military campaigns, the first of which was the siege and capture of Erivan in Persia by Murat IV in 1635, and he claims to have fought in twenty-two battles. But after each of these journeys he returned to Stamboul, and the largest part of his extant work is concerned with a description of his native city, its people and their life. He tells us that he travelled for forty years, passed through the countries of eighteen monarchs, and heard one hundred and forty-seven languages, but that nothing which he saw on his journeys compared in beauty or interest with his birthplace. He finally seems to have settled down in the Thracian city of Edirne, where he spent the closing decade of his life, dying there in about 1680 at the age of seventy. Evliya is thought to have spent those last years completing the Seyahatname, after the completion of those travels which had in fact taken him through ‘the seven climates and the four quarters of the earth’.

But one wonders why Evliya left Stamboul as his life was drawing to a close. Perhaps, like so many writers before and after his time, he may have felt it necessary to escape from the pleasant company of his friends in order to get on with his work. But how Stamboul must have missed Evliya when he left for the last time, and how Evliya must have missed Stamboul.

The base of the Egyptian Obelisk in the Hippodrome

2

Talismans

Evliya Efendi begins his Seyahatname by giving what he calls ‘an account of the ancient city and seat of Empire of the Macedonian Greeks, the well-guarded Constantinople, the envy of all the kings of the Land of Islam’. Evliya’s version of the city’s foundation is, as we might expect, fabulous. He informs us that ‘all the ancient Greek historians are agreed that it was first built by Solomon, son of David, 1600 years before the birth of the Prophet. They say he caused a lofty palace to be erected by Genii, on the spot now called Saray Point, in order to please the daughter of Saidun, sovereign of Feridun, an island in the Western Ocean.’

At the time when Evliya was writing his description of the city, in the middle of the seventeenth century, memories of the Byzantine Empire had all but taken on the quality of legend. Aside from perhaps a score of churches, most of them by then converted into mosques, there remained in the city only some scattered ruins of imperial Byzantium. And so, in his customary way, Evliya invested these ruins with fabulous histories, claiming that many of them were magical talismans which had since antiquity protected the city of Constantinople. Many of Evliya’s supposed talismans are still standing today, although, from the condition of the modern town, they would seem to have lost their magical powers. But there are those of us for whom some magic still remains, for these talismanic ruins can evoke the fabled past of Byzantium, especially with Evliya Efendi at one’s side.

Pride of place among these ancient monuments should perhaps be given to the Column of Constantine, although Evliya ranks it only second among the talismans of the city. This column was dedicated by Constantine the Great on May 11 in the year AD330, the day on which Constantinople officially became the capital of the Roman Empire. The column, which was originally surmounted by a statue of the Emperor himself, stood in the centre of the Forum of Constantine, now a minor intersection on the Avenue of the Janissaries. The identity of the column and its historical significance were almost forgotten by Evliya’s time. Nevertheless, the name of Constantine the Great still seems to have been associated with it, as we can see from Evliya’s description: ‘In the Poultry Market there is a needle-like column formed of many pieces of red emery stone, a hundred royal cubits high. This was damaged by the earthquake which occurred on the two nights during which the Pride of the World (Mohammed) was called into existence; but the builders girt it round with iron hoops, as thick as a man’s thigh, so that it is still firm and standing. It was erected 140 years before the era of Iskender (Alexander the Great). Kostantin (Constantine the Great) placed a talisman on top of it in the form of a starling, which once a year clapped its wings and brought all the birds in the air to the place, each with three olives in its beak and talons.’

The second of the city’s surviving imperial columns, the Column of Marcian, stands in the centre of a quiet little crossroads near Beyazıt Square. This column, huge as it is, was completely lost sight of for centuries and almost forgotten, for it stood in the garden of a private house. But then, in the great fire of 1908, the surrounding houses were burned to the ground and the column was once again exposed to public view. (Do we detect here the crime of an antiquarian-arsonist?) On the pedestal of the column there are still visible the figures of two Nikes in high relief; one of them holds a basket decorated with a cross and myrtle leaves. Below these figures we can make out the outlines of an inscription in Latin. It reads: ‘Tatianus Decius raised this column for the Emperor Marcian. December 450–July 452.’ The Turks call this column Kız Taşi, or the Maiden’s Column, because of the reliefs of the two Winged Victories which appear on the pedestal. This has led them to confuse the Kız Taşi with the famous Column of Venus, which also stood in this neighbourhood; this column reputedly possessed the power of being able to distinguish true virgins from false ones. Evliya Efendi listed the Maiden’s Column as the third of the city’s talismans, giving this brief description: ‘At the head of the Saddler’s Bazaar, on the summit of a column stretching to the skies, there is a chest of white marble in which the unlucky daughter of King Puzantin lies buried; and to preserve her remains from ants and serpents was this column made a talisman.’ Talismanic protector of a dead princess and indicator of false virgins; this is indeed a fabulous column!

Of the other imperial columns which once studded the city only a solitary but fascinating fragment remains. This is the base of the Column of Arcadius, which stands in the lovely old district of Samatya. This column was erected by the Emperor Arcadius in 402 to commemorate his victories over the Goths and Visigoths. At the top of the column there was an enormous Corinthian capital surmounted by a colossal equestrian statue of Arcadius, placed there in 421 by his son, Theodosius the Lesser. This statue was eventually toppled from the column and destroyed in 704. The column itself remained standing for another thousand years, until it was deliberately demolished in 1715, when it was feared that it might fall on the neighbouring houses. All that remains today is the base of the monument, a battered mass of blackened stone completely overgrown with ivy and wedged in between a bakery and an old wooden tenement. Evliya, who saw the column before it was destroyed, numbered it first in his list of the city’s talismans. After describing the column itself, he gives this account of its talismanic powers: ‘On the summit of the column there was anciently a fair-cheeked figure of one of the beauties of the age, which once a year gave a sound, on which several hundred thousand kinds of birds, after flying round and round the image, fell down to earth and being caught by the people of Rum (Rome), provided them with an abundant meal. After, in the age of Kostantin, the monks placed bells upon it, in order to give alarm on the approach of an enemy. Subsequently, on the birth of the Prophet, there was a great earthquake by which the statue and all the bells on top of the figure were thrown topsy-turvy and the column itself broke into pieces; but being formed by the talismanic art it could not be destroyed and part of it remains as an extraordinary spectacle to this day.’

Evliya tells us that another half-dozen talismans are to be found in Altımermer, the district of the Six Marbles. The eponymous marbles, presumably columns, from which the district takes its name probably stood in or near the enormous Roman reservoir which is located in that area. This reservoir, anciently called the cistern of Mocius, was constructed towards the end of the fifth century, during the reign of Arcadius. Though the columns which Evliya describes are no longer to be found in the reservoir itself, there is a tradition which holds that they are the ones which now stand in the colonnade of the nearby mosque of Hekimoğlu Ali Paşa. Evliya outdoes himself in describing these talismanic columns, telling us that ‘every one of them was an observatory, made by some of the ancient sages’. The sages with whom Evliya associates these talismans are a most formidable group, namely: Hippocrates, Socrates, Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle, Galen and King Philip of Macedonia, who would surely be surprised to find himself in the company of such distinguished intellectuals. On one of the columns stood a brass fly which, by its incessant humming, drove away all flies from the city, and on the second stood the figure of a gnat, which performed a similar service. On a third column stood the figure of a wolf which protected the flocks of the city from the attacks of real wolves. On a fourth column there was the figure of a stork which once a year let out a cry, whereupon all the storks within the city fell dead. Evliya tells us that this is the reason why storks do not build their nests within the city walls but prefer the suburb of Eyüp, on the upper reaches of the Golden Horn. These last two talismans would appear to be effective even now in protecting the town, for wolves are never seen in the streets of Stamboul and storks still nest only in Eyüp. But in warm weather the town swarms with flying insects, and so the brass fly and gnat must have disappeared or lost their powers. As Evliya tells us: ‘Wonderful talismans were destroyed, they say, in the time of that asylum of apostleship (Mohammed) and are now buried in the earth.’

The fifth and sixth talismans in Altımermer performed services of a different kind, according to Evliya: ‘On one of these columns were the figures of a youth and his mistress in close embrace. Whenever there was any coolness or quarrelling between man and wife, they were sure that very night to have their afflicted hearts restored by love if either of them went and embraced this column, which was moved by the spirit of Aristotle … Two figures in tin were placed on another column; one was a decrepit old man, bent double; and opposite to it was a camel-lip, sour-faced hag, no straighter than her companion. When a man and wife did not lead a happy life together a separation was sure to take place if either embraced this column, which was placed there by the sage Galen.’

Gypsy houses leaning against Byzantine walls

Although Evliya originally told us that there were six talismans at Altımermer, we find in reading his account that there were actually seven. This extra talisman was a brazen cock placed there by Socrates. As Evliya informs us: ‘This cock clapped its wings and crowed once in every twenty-four hours, and on hearing it all the cocks in Istanbul started to crow. And it is a fact that all the cocks there crow earlier than those of other places, setting up their ku-kirri-ku at midnight, and thus warning the sleepy and the forgetful of the approach of dawn and the hour of prayer.’ We are told by a sleepy and forgetful friend in this neighbourhood that the brazen cock of Socrates must still be active, for he is awakened long before dawn each day by cocks crowing in the cistern of Altımermer. The cistern, which has been dry for centuries, now serves as a fruit orchard and vegetable garden. A picturesque farm village has grown up within the cistern, a curiously rural community isolated in its vernal, subterranean world, providing a pleasant contrast with the densely populated urban slum around it. The tops of the smoking chimneys, the minaret of the village mosque, and the upper branches of the flowering fruit trees reach up barely to the level of the surrounding streets. Evliya Efendi tells us that we can descend into this little arcadia down a stone staircase called the Forty Steps, although, as he hastens to add, the actual number of steps is fifty-four. The Turks call this lovely place Çukurbostan, or the Sunken Garden.