1,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Diamond Book Publishing

- Sprache: Englisch

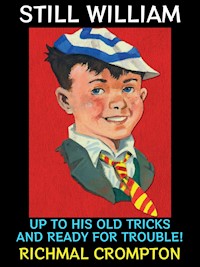

William's natural desire to do the right thing leads him into serious trouble, as usual, and when blackmail and kidnapping are involved, it's no surprise. Even when he turns over a new leaf, the consequences are dire. But it's his new neighbour, Violet Elizabeth Bott, who really causes chaos – and no one will believe that it's not William's fault . . . Richmal Crompton's Still William is a collection of fourteen brilliant Just William stories with an introduction by Sir Tony Robinson, appealing contemporary cover art by Chris Judge, along with the original inside illustrations by Thomas Henry. There is only one William. This tousle-headed, snub-nosed, hearty, lovable imp of mischief has been harassing his unfortunate family and delighting his hundreds of thousands of admirers since 1922.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Richmal Crompton

Still William Preview

Up to his Old Tricks and Ready for Trouble

Table of contents

CHAPTER I. THE BISHOP’S HANDKERCHIEF

By

Richmal Crompton

Table of Contents

CHAPTER I. THE BISHOP’S HANDKERCHIEF

CHAPTER II. HENRI LEARNS THE LANGUAGE

CHAPTER III. THE SWEET LITTLE GIRL IN WHITE

CHAPTER IV. WILLIAM TURNS OVER A NEW LEAF

CHAPTER V. A BIT OF BLACKMAIL

CHAPTER VI. “WILLIAM THE MONEY-MAKER”

CHAPTER VII. THE HAUNTED HOUSE

CHAPTER VIII. WILLIAM THE MATCH-MAKER

CHAPTER IX. WILLIAM’S TRUTHFUL CHRISTMAS

CHAPTER X. AN AFTERNOON WITH WILLIAM

CHAPTER XI. WILLIAM SPOILS THE PARTY

CHAPTER XII. THE CAT AND THE MOUSE

CHAPTER XIII. WILLIAM AND UNCLE GEORGE

CHAPTER XIV. WILLIAM AND SAINT VALENTINE

CHAPTER I. THE BISHOP’S HANDKERCHIEF

Until now William had taken no interest in his handkerchiefs as toilet accessories. They were greyish (once white) squares useful for blotting ink or carrying frogs or making lifelike rats to divert the long hours of afternoon school, but otherwise he had had no pride or interest in them.

But last week, Ginger (a member of the circle known to themselves as the Outlaws of which William was the leader) had received a handkerchief as a birthday present from an aunt in London. William, on hearing the news, had jeered, but the sight of the handkerchief had silenced him.

It was a large handkerchief, larger than William had conceived it possible for handkerchiefs to be. It was made of silk, and contained all the colours of the rainbow. Round the edge green dragons sported upon a red ground. Ginger displayed it at first deprecatingly, fully prepared for scorn and merriment, and for some moments the fate of the handkerchief hung in the balance. But there was something about the handkerchief that impressed them.

“ Kinder—funny,” said Henry critically.

“ Jolly big, isn’t it?” said Douglas uncertainly.

“’ S more like a sheet,” said William, wavering between scorn and admiration.

Ginger was relieved. At any rate they had taken it seriously. They had not wept tears of mirth over it. That afternoon he drew it out of his pocket with a flourish and airily wiped his nose with it. The next morning Henry appeared with a handkerchief almost exactly like it, and the day after that Douglas had one. William felt his prestige lowered. He—the born leader—was the only one of the select circle who did not possess a coloured silk handkerchief.

That evening he approached his mother.

“ I don’t think white ones is much use,” he said.

“ Don’t scrape your feet on the carpet, William,” said his mother placidly. “I thought white ones were the only tame kind—not that I think your father will let you have any more. You know what he said when they got all over the floor and bit his finger.”

“ I’m not talkin’ about rats,” said William. “I’m talkin’ about handkerchiefs.”

“ Oh—handkerchiefs! White ones are far the best. They launder properly. They come out a good colour—at least yours don’t, but that’s because you get them so black—but there’s nothing better than white linen.”

“ Pers’nally,” said William with a judicial air, “I think silk’s better than linen an’ white’s so tirin’ to look at. I think a kind of colour’s better for your eyes. My eyes do ache a bit sometimes. I think it’s prob’ly with keep lookin’ at white handkerchiefs.”

“ Don’t be silly, William. I’m not going to buy you silk handkerchiefs to get covered with mud and ink and coal as yours do.”

Mrs. Brown calmly cut off her darning wool as she spoke, and took another sock from the pile by her chair. William sighed.

“ Oh, I wouldn’t do those things with a silk one,” he said earnestly. “It’s only because they’re cotton ones I do those things.”

“ Linen,” corrected Mrs. Brown.

“ Linen an’ cotton’s the same,” said William, “it’s not silk. I jus’ want a silk one with colours an’ so on, that’s all. That’s all I want. It’s not much. Just a silk handkerchief with colours. Surely——”

“ I’m not going to buy you another thing, William,” said Mrs. Brown firmly. “I had to get you a new suit and new collars only last month, and your overcoat’s dreadful, because you will crawl through the ditch in it——”

William resented this cowardly change of attack.

“ I’m not talkin’ about suits an’ collars an’ overcoats an’ so on——” he said; “I’m talkin’ about handkerchiefs. I simply ask you if——”

“ If you want a silk handkerchief, William,” said Mrs. Brown decisively, “you’ll have to buy one.”

“ Well!” said William, aghast at the unfairness of the remark—“Well, jus’ fancy you sayin’ that to me when you know I’ve not got any money, when you know I’m not even going to have any money for years an’ years an’ years.”

“ You shouldn’t have broken the landing-window,” said Mrs. Brown.

William was pained and disappointed. He had no illusions about his father and elder brother, but he had expected more feeling and sympathy from his mother.

Determinedly, but not very hopefully, he went to his father, who was reading a newspaper in the library.

“ You know, father,” said William confidingly, taking his seat upon the newspaper rack, “I think white ones is all right for children—and so on. Wot I mean to say is that when you get older coloured ones is better.”

“ Really?” said his father politely.

“ Yes,” said William, encouraged. “They wouldn’t show dirt so, either—not like white ones do. An’ they’re bigger, too. They’d be cheaper in the end. They wouldn’t cost so much for laundry—an’ so on.”

“ Exactly,” murmured his father, turning over to the next page.

“ Well,” said William boldly, “if you’d very kin’ly buy me some, or one would do, or I could buy them or it if you’d jus’ give me——”

“ As I haven’t the remotest idea what you’re talking about,” said his father, “I don’t see how I can. Would you be so very kind as to remove yourself from the newspaper rack for a minute and let me get the evening paper? I’m so sorry to trouble you. Thank you so much.”

“ Handkerchiefs!” said William impatiently. “I keep telling you. It’s handkerchiefs. I jus’ want a nice silk-coloured one, ’cause I think it would last longer and be cheaper in the wash. That’s all. I think the ones I have makes such a lot of trouble for the laundry. I jus’——”

“ Though deeply moved by your consideration for other people,” said Mr. Brown, as he ran his eye down the financial column, “I may as well save you any further waste of your valuable time and eloquence by informing you at once that you won’t get a halfpenny out of me if you talk till midnight.”

William went with silent disgust and slow dignity from the room.

Next he investigated Robert’s bedroom. He opened Robert’s dressing-table drawer and turned over his handkerchiefs. He caught his breath with surprise and pleasure. There it was beneath all Robert’s other handkerchiefs—larger, silkier, more multi-coloured than Ginger’s or Douglas’s or Henry’s. He gazed at it in ecstatic joy. He slipped it into his pocket and, standing before the looking-glass, took it out with a flourish, shaking its lustrous folds. He was absorbed in this occupation when Robert entered. Robert looked at him with elder-brother disapproval.

“ I told you that if I caught you playing monkey tricks in my room again——” he began threateningly, glancing suspiciously at the bed, in the “apple-pie” arrangements of which William was an expert.

“ I’m not, Robert,” said William with disarming innocence. “Honest I’m not. I jus’ wanted to borrow a handkerchief. I thought you wun’t mind lendin’ me a handkerchief.”

“ Well, I would,” said Robert shortly, “so you can jolly well clear out.”

“ It was this one I thought you wun’t mind lendin’ me,” said William. “I wun’t take one of your nice white ones, but I thought you wun’t mind me having this ole coloured dirty-looking one.”

“ Did you? Well, give it back to me.”

Reluctantly William handed it back to Robert.

“ How much’ll you give it me for?” he said shortly.

“ Well, how much have you?” said Robert ruthlessly.

“ Nothin’—not jus’ at present,” admitted William. “But I’d do something for you for it. I’d do anythin’ you want done for it. You just tell me what to do for it, an’ I’ll do it.”

“ Well, you can—you can get the Bishop’s handkerchief for me, and then I’ll give mine to you.”

The trouble with Robert was that he imagined himself a wit.

The trouble with William was that he took things literally.

The Bishop was expected in the village the next day. It was the great event of the summer. He was a distant relation of the Vicar’s. He was to open the Sale of Work, address a large meeting on temperance, spend the night at the vicarage, and depart the next morning.

The Bishop was a fatherly, simple-minded old man of seventy. He enjoyed the Sale of Work except for one thing. Wherever he looked he met the gaze of a freckled untidy frowning small boy. He could not understand it. The boy seemed to be everywhere. The boy seemed to follow him about. He came to the conclusion that it must be his imagination, but it made him feel vaguely uneasy.

Then he addressed the meeting on Temperance, his audience consisting chiefly of adults. But, in the very front seat, the same earnest frowning boy fixed him with a determined gaze. When the Bishop first encountered this gaze he became slightly disconcerted, and lost his place in his notes. Then he tried to forget the disturbing presence and address his remarks to the middle of the hall. But there was something hypnotic in the small boy’s gaze. In the end the Bishop yielded to it. He fixed his eyes obediently upon William. He harangued William earnestly and forcibly upon the necessity of self-control and the effect of alcohol upon the liver.