3,30 €

Mehr erfahren.

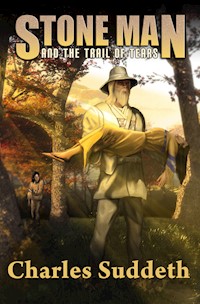

- Herausgeber: Dancing Lemur Press LLC

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

Driven to Stone Man’s trail...

After U.S. soldiers attack twelve-year-old Tsatsi’s Cherokee village, his family flees to the Smokey Mountains. Facing storms, flood, and hunger, they’re forced to go where Stone Man, a monstrous giant, is rumored to live.

His family seeks shelter in an abandoned village, but soldiers hunt them down. Tsatsi and his sister Sali escape, but Sali falls ill and is kidnapped by Stone Man. Tsatsi gives chase and confronts the giant, only to learn this monster isn’t what he seems.

Their journey is a dangerous one. Will Tsatsi find the strength to become a Cherokee warrior? And will they ever find their family?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 211

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Charles Suddeth

DANCING LEMUR PRESS, L.L.C.

Pikeville, North Carolina

http://www.dancinglemurpressllc.com/

“The scenery was wonderful and I loved the action-packed scenes. As sad as the story was, I liked how all the characters were still hopeful and did not give up. We should all have the mentality of these characters. I adored the ending and it warmed my heart! 5 stars.” – Pages for Thoughts reviews

"The story starts off at a frantic pace and doesn't let up, sure to pull in readers who normally don't read historical fiction. The ending is perfectly executed.” - Greg Pattridge, Always in the Middle reviews

“This is a historical adventure which draws in and allows the reader to feel as if they are really there.” – Tonja Drecker, author of Music Boxes

“I found this story enjoyable, educational, and inspiring. It inspired me to reach out to others and help people in need, even if they’re strangers” – The Wood Between the World reviews

Copyright 2019 by Charles Suddeth

Published by Dancing Lemur Press, L.L.C.

P.O. Box 383, Pikeville, North Carolina, 27863-0383

http://www.dancinglemurpressllc.com/

ISBN 9781939844637

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system in any form–either mechanically, electronically, photocopy, recording, or other–except for short quotations in printed reviews, without the permission of the publisher.

This book is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Cover design by C.R.W.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataNames: Suddeth, Charles, author.Title: Stone Man and the Trail of Tears / Charles Suddeth.Description: Pikeville, North Carolina : Dancing Lemur Press, L.L.C., [2019] | Summary: While fleeing from the soldiers who attacked their village, twelve-year-old Cherokee Tsatsi and his sister are separated from the rest of their family and encounter a monster who is not what he seems. Identifiers: LCCN 2019010379 (print) | LCCN 2019013849 (ebook) | ISBN 9781939844637 (ebook) | ISBN 9781939844620 (pbk. : alk. paper)Subjects: LCSH: Trail of Tears, 1838-1839 Juvenile fiction. | Cherokee Indians--Juvenile fiction. | CYAC: Trail of Tears, 1838-1839--Fiction. | Cherokee Indians--Fiction. | Indians of North America--Southern States--Fiction. | Brothers and sisters--Fiction. | Family life--Fiction.Classification: LCC PZ7.1.S83 (ebook) | LCC PZ7.1.S83 St 2019 (print) | DDC [Fic]--dc23LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019010379

I dedicate Stone Man to my great-great grandfather, William (Bill) Pennington (1830-1930), my last full-blood Cherokee ancestor. He was born in a Cherokee village somewhere in the mountains, possibly Virginia or Kentucky. His family moved north about 1838, around the time of the Trail of Tears. They never told him the village’s name or location. Bill remarried late in life and had a second family. I was fortunate to meet his youngest son, Mack Pennington, who told me about Bill.

Table of Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Historical Note

Vocabulary

Cherokee Words

About the Author

Chapter One

Fall 1838

Hoofbeats and yelling woke me in the middle of the night.

I leapt to my feet. Doda, my father, hurried to the door of our single-room log cabin.

“Yonega. Yonega,” a warrior on horseback cried, warning us about white soldiers.

Doda waved him on. The rider rode off to warn the rest of our village. People were spilling out of cabins, only to be surrounded by soldiers.

I had heard about soldiers burning Cherokee homes and taking them to stockades to steal our lands and send us west across the Mississippi River. I never believed it could happen to us. I froze.

“Soldiers are patrolling the roads. I loaded the canoes earlier. We must go,” Doda shouted.

Aytsi, my mother, slipped homespun haversacks around our necks. They held cornmeal and supplies. I grabbed a second haversack to save some of my belongings such as my blowgun and an extra pair of moccasins.

“Run,” shouted Doda as he picked up my baby brother, Tsegson, and carried him out, leaving the door wide open. Tsegson slumbered on Doda’s shoulder, oblivious to the commotion.

“Tsatsi, stay with Sali,” Aytsi said.

My sister, Sali, was two years younger than me. She clutched her haversack without complaint and stood by me. Her shoulders trembled.

Doda had named me Tsatsi, meaning George, after the American chief George Washington. Although I was only twelve, the strong name made me feel like a warrior.

My six-year-old sister, Nanyehi, whimpered and buried her face in Aytsi’s long dress. Aytsi took her hand and rushed into the night. Sali and I followed close behind her. Dodging cornstalk spikes left over from harvest, we dashed for the creek.

Horses snorting and men shouting made me look over my shoulder. A single file of torches snaked toward our cabin. I hoped they didn’t spot us before we climbed in our canoes.

Soldiers torched the cabin next to ours, and the sky grew so bright I blinked from the glare.

We kept running.

Behind us, soldiers yelled.

More hoofbeats.

“Doda, do you hear them?” I cried out as fear pounded my heart.

“Don’t stop!”

Our cabin, the only home I had ever known, burst into flames. The sky turned to daytime. The heat from the flames licked the back of my neck.

“Let’s surrender while we can,” Aytsi said.

“We cannot go back. They will shoot us for trying to escape,” Doda hollered.

We didn’t slow down. Reflecting off the dewy grass, the moon had dwindled to a sliver, and darkness shrouded Redbird Creek. Firelight from the burning cabins helped me find the path and avoid boulders lining the banks.

Doda and I shoved two dugout canoes into the icy water. He took the rear of the first canoe, with Aytsi sitting in front. Tsegson sat between them; his eyes were half-closed despite everything.

I sat in the back of the second canoe. Sali took the front and Nanyehi knelt between us. Taking a deep breath, I waited for Doda’s lead. Sali held a paddle as Nanyehi quivered like a wind-borne leaf and hugged one of our packs.

Using a paddle, Doda pushed away from the bank. A moment later, I shoved my canoe away.

The wind shifted, carrying the sweaty scent of galloping horses toward us. A whinny and more voices carried through the damp night air.

We were too late.

Redbird Creek

Horses splashed in the creek. The soldiers who had torched our cabin closed in on us.

Doda’s paddle smacked into the water. A moment later, I jammed my paddle in and pushed my canoe into the middle of the creek. The soldiers hadn’t fired yet. With the darkness and their muzzle-loading rifles, they couldn’t afford to waste shots.

Hearing more noises, I glanced back. One of the soldiers cursed and whipped his horse. It whinnied and treaded into the marsh bordering the creek banks, a stone’s throw from my canoe. Other soldiers followed. I couldn’t see rifles, but I hunched down to keep from getting shot. Sali doubled over until the canoe shielded her head.

“Nanyehi, lie down,” I whispered.

Packs of food, blankets and other supplies lined the middle of my canoe. Nanyehi yelped and wedged herself between the bundles. Our canoe crept downriver. The soldiers could aim, fire, and reload before we could move out of range.

Lightning lit up the creek, outlining trees hanging over the water and rocks taller than me. Doda’s canoe kept a canoe-length ahead of us. I paddled as fast as I could, and Sali helped with her own paddle.

Thunder rattled our canoe. Nanyehi squealed and crawled to Sali.

Cold sheets of rain stung my face and hands as the other canoe pulled farther from us. One soldier stood on a boulder jutting into the creek and took aim. I heard the loud “click” of the rifle’s hammer and braced for the shot.

Nothing.

When I looked again, I could no longer see him. I hoped the rain had made his gunpowder too wet. Or perhaps he’d changed his mind about shooting children.

I wrapped a cloak around me to stop shivering. Ankle deep in rainwater, I lifted my feet and let the water drain into the canoe’s floor. Doda had hewn the canoe from solid ash wood, but I didn’t know how much water it could hold. With three of us and our supplies, our canoe rode dangerously low in the water.

“Sali, start bailing before we sink,” I shouted.

“With what?” She waved her empty hands.

“Drinking gourds,” I snapped. “Hurry up.”

Sali grabbed a gourd. “The water’s freezing.”

“If we sink, your body will be in that freezing water.” I stopped paddling so I could help bail.

“I’ll bail.” Nanyehi used her drinking gourd.

The rain didn’t let up. Though Sali and Nanyehi made little headway, I hoped they would keep the water from filling our canoe.

I lost sight of Doda’s canoe. When lightning flashed, I realized they had gone around a bend. Even though my arms cramped, I didn’t dare slow down. Most of the families in Redbird owned canoes, so the soldiers could find one easily enough and chase us down. I looked back as lightning flashed. No soldiers in sight. For now.

“My arms are aching,” Sali said.

“Me, too,” Nanyehi chirped.

“Keep bailing,” I yelled. “Do you want us to drown?”

Sali continued bailing at a slower pace, and Nanyehi used one hand.

Since rain filled my eyes, I could scarcely see in front of my face. Rainwater fell into my open mouth as I panted. I spit it out to keep from choking.

The creek straightened, and I caught sight of the other canoe. It had ceased moving. The fire in the pit of my belly let up. I’d feared that Doda’s canoe had gone too far ahead for us to catch up. Doda’s paddle lay across his right shoulder. We pulled beside them.

“Are you all right?” Doda asked.

I nodded. My hands had blistered so badly I couldn’t stand to grip the paddle, but I refused to admit that to a warrior like Doda.

“My hands hurt,” Sali said.

“Mine, too.” Nanyehi held her arms straight up.

Aytsi leaned over from the other canoe, but she couldn’t reach Nanyehi. “Fix the child’s cloak.”

Sali tightened the cloak around Nanyehi’s neck until it hung from her shoulders.

While stopped, I continued to bail water.

“The rain should ease up soon,” Doda said. “But we have to keep going.”

“Me cold,” Tsegson hollered.

I couldn’t stop shivering, either. Longing to be back beside the fireplace, warm and drowsy and safe, I yawned.

“Before dawn, we’ll stop and light a fire,” Doda said.

We journeyed another mile or two. Nanyehi quit bailing and sat hunched over as if she had chilled, but Sali didn’t stop. Trailing again, I almost caught up with Doda’s canoe. But the current sped up, and our canoe twisted. We floated downstream at an angle. I paddled harder, but the canoe refused to straighten.

Its side scraped against a boulder. The shudder crawled up my legs.

The canoe tilted, and more water sloshed inside. How far ahead was Doda? What if the canoe capsized?

“Do something,” Sali shouted.

I shifted left.

The canoe didn’t budge.

“Nanyehi, hold on or you’ll fall out,” I hollered.

She grabbed onto the edge pointing to the sky.

“Sali, help me shake it loose from the rock,” I said.

We struck the left side with our shoulders as hard as we could.

The canoe didn’t budge.

“Again,” I cried.

Sali and I tackled the inside of the canoe again.

It moved.

We kept our shoulders pressed against the canoe’s wall. Even Nanyehi rammed it with her thin shoulder. The canoe slowly righted itself.

“Hold on,” I shouted.

The canoe bounced back, going too far the other way. I double-checked the sides. The rock had slashed a deep gash in the wood at water level, but not all the way through.

Nanyehi started crying.

“Hold her,” I told Sali.

“Are we going to sink?” She wrapped her arms around Nanyehi and kissed her cheek. I pushed the canoe farther away from the boulder with the paddle. “It’s not leaking yet.”

The other canoe had stopped. I caught up and steered my canoe beside theirs.

A huge oak lay across the creek. Since leaves still clung to the branches, the tree probably fell during the storm. I couldn’t see around it. I didn’t think we could go under the trunk, and we couldn’t portage canoes, not without several strong men.

The tree had us trapped.

Chapter Two

Deep in the Night

The fallen tree looked impossibly long. Nanyehi clung to Sali’s arm.

Sali murmured, “What are we going to do?”

“Doda, can we push through the tree with our canoes?” I shouted.

“Too many limbs in the water. Somebody might get speared in the dark,” he shouted back.

The rain had stopped, though water still pooled onto the canoe’s floor. I ached too much to move.

“Follow me.” Doda turned his canoe toward the bank on our left.

The moon crept out of the clouds and lit up the surrounding trees. The trees cast murky shadows on the water. The shadows might be soldiers or wolves or most anything.

“I’m afraid.” I pointed, though it was too dark for anyone to see my fingers. “Soldiers might be waiting for us.”

“Tsatsi has a point,” Aytsi said.

“We’re a few miles from the Nantahala,” Doda said in a hoarse voice.

The Nantahala River was much wider and deeper than Redbird Creek. Even in daylight, traveling by canoe on the rock-clogged Nantahala could be risky.

“If we go up the Nantahala, we won’t be far from the town of Nantahala. I’m certain troops have already been there,” he said. “They likely burned it down.”

“I remember visiting Nantahala for the Green Corn Festival. How about the Town Center that sat on a high mound?”

“The soldiers probably burned it, too,” Doda replied.

“Then where can we go?” Except for Nantahala, I had never been any place outside our village.

“Into the mountains,” said Doda. “We can cross the Little Tennessee River and hide in the Smokies, but it will take days.”

“We can’t winter up there,” Aytsi said. “We’ll freeze.”

“Just for a spell,” said Doda. “One day we can go home and build a new cabin. Tsatsi’s old enough to help.”

I ought to be old enough to fight the soldiers who torched our home, too. But I held my tongue.

Doda glided his canoe onto the bank.

I did the same as I tried to peer through the forest. My canoe hit the bank and shuddered.

“Doda,” I whispered as I held the canoe in place with my paddle stuck in the muddy bank. “Let me check beyond the line of trees ahead.”

He gazed into the darkness. “I suppose. But be careful. Use your eyes and ears and head.”

“Watch the canoe,” I told Sali.

She stuck her paddle into the muck along the riverbanks water and held onto it to keep the canoe from drifting away. Nanyehi hugged one of the canvass packs and stayed in the canoe.

I leapt onto a flat rock and darted between two thick trees. Their roots snaked around a greenish boulder. I stood between the trees and listened. Normal sounds—frogs, night birds, and countless bugs—broke the quiet.

I peeked around a moss-covered tree trunk. I couldn’t see in the dark, but the musty odor of water clung to my nose. I crept to the next tree and saw nothing except the lofty black shadows of trees. After a few moments, I returned to my family.

Aytsi and Doda had already unloaded the canoes. Everyone stared at me, even the two little ones.

“Nothing,” I said.

“Let’s get the canoes out of the way.” Doda motioned with his hand.

Doda and I pushed while Sali and Aytsi pulled. Tsegson tried to help, but Nanyehi gripped his hand and led him out of the way. We hauled the canoes out of the creek, but it took several minutes. Minutes we didn’t have to spare.

We turned them upside down and covered them with loose branches. As Doda had said, I hoped someday we could go back and rebuild the village of Redbird.

Everyone but Tsegson carried a pack or a haversack.

“Follow me.” Doda pointed toward the mountains where no one lived.

In the Forest

The trees grew so close together, Doda hacked branches out of our way with an axe. Still, we couldn’t find a trail. We pushed through a thicket of brambles that snagged at our clothes and stumbled upon a deer path threading through the edge of the woods. We followed it for a while. After crossing a steep gully, we lost the path in high weeds.

Doda trudged through the night without halting. Aytsi’s dress caught on the jagged edge of a broken rock protruding from a boulder. She pulled it loose without losing a step.

Tsegson stopped, squatting in front of me, almost tripping me. I picked him up and slung him over my shoulder without slowing. I kept glancing back. If soldiers attacked, I planned to hide behind a stout tree and knock the first man off his horse.

“My legs hurt,” Nanyehi whined.

Doda already carried the biggest pack, so I sighed and handed Tsegson to Sali.

“I’m tired, too,” Sali murmured, but she slung him over her shoulder.

Though she outweighed Tsegson, I picked up Nanyehi.

Our path steepened as we climbed out of Redbird Creek’s valley. A reddish morning sun peeked over the trees, making it easier for soldiers to spot us, capture us. If we reached the mountains, we could hide out for weeks. Then I realized the cloud-covered peaks must be farther away than they looked. At least a day’s journey.

I had hunted with Doda, and he taught me how to keep out of sight and scout for deer, turkeys, and small game. Now, we were making so much noise we scared the game, flushing them away like hounds driving rabbits out of burrows.

After a few minutes, Sali put Tsegson down. “I can’t tote him one more step.”

Tsegson quietly walked beside her.

Carrying Nanyehi hurt my back, but I held onto her. My arms ached, too. I started to tell Doda of my weariness when Doda veered toward a shallow fern-covered hollow and dropped his pack in a patch of sawgrass.

We collapsed onto the dewy ground. Nanyehi cuddled beside Sali. Tsegson climbed onto Aytsi’s side and tried to wrestle with her, but she closed her eyes and ignored him.

“Me hungry.” Tsegson rubbed his belly.

“Me, too,” Nanyehi whined.

Aytsi sighed, but she didn’t speak.

We rested a few minutes, long enough to catch our breath and stretch our cramped legs.

“I’ll give you a few minutes more to rest,” Doda said. “Then we’ll keep going until we find a place with water and room for a campfire.”

I figured that he didn’t want to say it aloud, but we needed to travel by night. Fatigue grabbed hold of me. I stretched out on my back to get a little rest.

I thought about my friends in Redbird. Did they get sent to a stockade or escape? Or had the soldiers killed them? Some questions were better left unanswered.

“Let’s go.” Doda clapped once. “We need to get as far away from here as we can.”

Tsegson toddled two steps and staggered. I picked him up.

Nanyehi stayed beside me as if I could pick her up, too. I wished I could. She sometimes liked to play games with me. Back home, she would hurl her cornhusk doll at my face and giggle.

Leaves quilted the ground in red, yellow, and orange. We tripped on stray rocks, fallen branches, and groundhog holes. Aytsi stumbled once and grabbed a tree branch to steady herself. Her long hair needed brushing and her eyes had sunk in. Doda took her pack, and she gifted him with a small smile. The path gradually became steeper as we entered the mountains.

The uphill trudge quickly tired me out. At a boulder-filled stream, we halted to drink the clear water. By then, daylight stole through the trees. Doda picked up his pack.

Doesn’t he ever tire out?

We stared at him. Even Aytsi. Tsegson wrapped his arms around Doda’s leg and squalled. I couldn’t carry him again. I didn’t think I could carry myself.

Nanyehi wouldn’t look at Doda. She played with her pigtails, with her lower lip jutted out and her little eyes darkened.

Doda sighed. “Let’s cross the creek and find a stand of trees to take shelter under.”

We hopped from stone to stone across the shallow water.

Sali crossed first and trotted into a patch of lofty pines. She spun around and plopped down in the middle of a thick carpet of pine needles. “Can we sleep here? I’m tuckered out.”

The needles would make a good bed, and we could dig down and hide. I longed to join her, but I stood beside Aytsi.

Doda patted her on the back. “Good idea. You and Tsatsi round up dry firewood.”

Water still dripped off everything from the storm. “Where can we find wood that’ll burn?” I asked.

“Find a hollow trunk. Look under fallen branches. If we don’t find dry wood, we’ll freeze.”

Sali gleaned a few wood scraps from inside a hollow sycamore. I gathered more from under a fallen pine branch. We carried them in our palms to Doda.

“That’s enough for a start but find more.” Using the flint, he carried in his haversack, he made a feeble flame in a pile of twigs.

I figured that under the downed pine branch, the needles on the ground had stayed dry. Sali and I scooped up handfuls and tossed them in the flames. After several trips, we had a fine blaze going. A hot one, too. The sooty smoke from pine needles stung my nose, though, so I turned and warmed my backside.

“Tsatsi, fetch water from the creek,” Aytsi said.

She wanted water to cook! I used a tight willow basket and trotted to the creek. I brought her two basket loads.

Aytsi mixed cornmeal and water together and baked ashcakes in the glowing coals. They didn’t taste like johnnycakes, but they filled our bellies. Doda sliced strips of dried venison, so we ate a regular meal. It tasted wonderful—the best meal I’d ever eaten.

Nanyehi licked her lips, “Ahh. I like that.”

Sali giggled and licked her lips, too. We all laughed, even Tsegson.

The smoke rose straight up and could be seen a long way. The wood and needles we used hadn’t dried enough. “Doda, what if the soldiers spot the smoke?”

“That’s a chance we’ll have to take. We don’t need frostbite,” he said.

Aytsi glanced across the creek, her head bowed.

Sali used a stick to push another ashcake out of the fire. “Without something to eat, I couldn’t go any farther.”

I shrugged, but I agreed with her. Sali handed me the ashcake and grabbed another for herself. They tasted better than the venison. I crumbled Tsegson’s ashcake so he could eat it.

When we finished eating, Doda sprinkled wet needles on the fire. It went out faster than I expected. Faster than I wanted.

“Everyone gather around the warm ashes, and we’ll nap,” Doda said.

Nanyehi and Sali slept with each other. Tsegson and I slept together. Since he fidgeted constantly, I didn’t like it, but we needed warmth.

I wrapped my arms around him and made sure he stayed closer to the warm embers than me. He held still and didn’t speak; the day had exhausted him, too.

“Osda sunohi,” I whispered goodnight.

“Gungayyu,” he whispered back, saying he loved me. I hugged him as tightly as I could. How could I begrudge carrying him across the mountains?

Before I realized it, I’d fallen asleep.

I woke sometime later. Though the sun still shone, I didn’t know how long I’d been asleep. Cold ashes sat in place of the fire.

I was alone.

Tsegson had taken off.

I assumed he had deserted me to be with Aytsi. I checked, but she didn’t have him.

Tsegson had disappeared.

High in the Mountains

Dodging countless rocks, tree stumps, and mud puddles, I circled the camp. Though I ran out of breath, I didn’t slow down, calling over and over again, “Tsegson, Tsegson.”

How far away could someone with short, chubby legs stray? What if soldiers or a cougar took him? Worry left a bitter taste on my tongue as sweat broke out on my skin, despite a cool breeze.

The creek! What little boy didn’t like to splash in water? I trotted to the creek’s banks. No one. I skipped across on the rocks and checked the trail we came in on.

Still no one.

We hadn’t climbed halfway up the mountain yet, but I doubted he would try to climb higher.

I recalled a Cherokee ritual, Going to Water. Men purified themselves in a creek in the morning, smudged themselves with tobacco smoke, and uttered a prayer. Tsegson must have watched Doda doing a Going to Water ceremony and copied him. I searched up and down the creek. No sign of him.

I circled the camp two or three times, again calling out, “Tsegson, Tsegson.”

No reply.

A lump lodged in my throat. If I couldn’t find him, I was going to run away and let the soldiers take me. I was too old to be that careless.

At the place where Sali and I discovered the dry needles, I tripped on a stick. I landed face-down in a patch of dead leaves and needles. I spat needles off my blistered lips.

Someone giggled.

I picked up the branch. Gazing up at me, Tsegson sat with his legs folded underneath him in the hollow Sali and I had made when we scooped up needles.

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)