Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

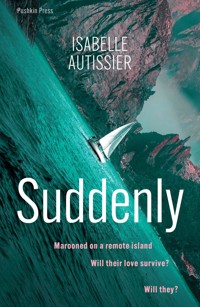

'A tense and exhilarating read' Le Figaro'You'll devour this novel' Express'This novel brings you to the rawest edges of what our humanity becomes when we're far from civilisation' Lire __________ A gripping story of survival set against the stark backdrop of the Antarctic Ocean, a couple shipwrecked on an island must trust each other with their lives A young couple sets out on a journey by yacht around Cape Horn, but the adventure of a lifetime soon becomes a fight for survival. When they are stranded on a freezing, desolate island in the South Atlantic Ocean, they find themselves having to rely on each other as never before. Will their relationship survive until help arrives-and will they? A stunning, harrowing tale of endurance from an expert in sailing, Suddenly tells the story of the people we become when faced with the awesome power of the natural world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 274

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

“Isabelle Autissier sails through literature the way she sails the ocean: with vigor, precision, and determination… The result: a tense and exhilarating read.”

Le Figaro

“An adventure novel somewhere between those of Jules Verne and Robert Louis Stevenson.”

Le Parisien

“There’s no question about it: Isabelle Autissier is an excellent writer… When it comes to describing nature, there’s no one like her… You’ll devour this novel.”

Express

“With a realism that will take your breath away, this novel brings you to the rawest edges of what our humanity becomes when we’re far from civilization… Alone at the helm, without ever losing sight of north, Isabelle Autissier proves that in addition to being a peerless sailor, she is also a great novelist.”

Lire Magazine Littéraire

“Unfolds like a thriller… Icy, captivating, punctuated by questions about nature’s deepest instincts—Isabelle Autissier steers this novel to perfection. Get on board.”

L’Obs

Suddenly

ISABELLE AUTISSIER

Translated from the French by Gretchen Schmid

Pushkin Press

Contents

Part I

There

They set out early. The day promises to be sublime, as days sometimes are in these wild latitudes; the sky is a deep blue, almost liquid, with the clearness particular to the southern Fifties. There isn’t so much as a wrinkle on the surface of the water, and the Jason, their boat, seems to float weightlessly on a carpet of dark sea. Without any wind, the albatrosses pedal calmly around the hull.

They pull the dinghy high up on the shore and walk around the old whaling station. The rusty sheet metal, gilded by the sun, is a mix of ochers, browns, and reds, giving off a jaunty air. Abandoned by man, the station has been taken over by animals, the same ones that for so long had been hunted, felled, disemboweled, and cooked in the enormous boilers that are now falling into ruin. As they wander from one pile of bricks to the next, they find collapsed sheds containing jumbles of pipes that no longer lead anywhere, in the middle of which groups of cautious penguins, families of fur seals, and elephant seals are lounging. They stay to watch the animals for some time, and it is late in the morning when they begin to go up the valley.

“Three solid hours,” Hervé, one of the few people to have ever been here, had told them. On the island, as soon as you get away from the coastal plain, there is no more green. The world becomes mineral: rocks, cliffs, peaks crowned by glaciers. They walk at a good clip, bursting into laughter when they see the color of a stone or the purity of a stream as though they’re kids skipping school to go on an adventure. When they arrive at the first steep slope, before they lose sight of the sea, they take another break. It’s so simple, so beautiful, almost inexpressible—the bay encircled by blackish drop‐offs, the water glinting silver in the light breeze that’s beginning to blow, the old station an orange splotch, and their good old boat, which seems to be sleeping, its wings folded under itself like the albatrosses from that morning. Off the coast, motionless white‐blue behemoths gleam in the light. There is nothing more peaceful than an iceberg in calm weather. The sky is streaked with enormous stripes—high, shadowless clouds, fringed with gold by the sun.

They stay for a long time, fascinated, savoring the sight. Probably a little too long. Louise notices that it is beginning to get gray in the west and her mountaineering antennae prick up, on alert.

“Don’t you think we should go back? The clouds are coming this way.”

Her tone is falsely cheerful, but a hint of unease comes through.

“Of course not! Come on, you’re always worrying about something. We won’t be so hot if there’s some cloud cover.”

Ludovic tries to keep impatience out of his voice, but frankly, he’s irritated by her anxiety. If he had always listened to her, they wouldn’t even be here, alone on this island at the edge of the world as though they were its king and queen. They would have never bought their boat or gone on this incredible journey. Sure, the sky is growing dark in the distance, but at worst they will just get wet. This is the price of adventure, it’s the whole point—to escape the torpor of the Parisian offices that was threatening to envelop them in comfortable softness, leaving them on the sidelines of their own lives. Their sixties would arrive and they would have nothing but regrets for never having lived, never having struggled, never having discovered anything. He forces himself to speak in a conciliatory tone.

“Hey, it’s now or never that we go see that amazing dry lake. Hervé told me that you wouldn’t see anything like it anywhere else—a maze of ice on the ground. You remember the incredible photos he showed us. And besides, I’m not lugging around the ice axes and crampons for nothing. It’ll be awesome, you’ll see, for you especially.”

He has touched a nerve. She is the mountaineer. He had chosen the destination with her in mind: a southern but mountainous island with a jumble of peaks, each purer than the last, right in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, at a latitude of more than fifty degrees south.

It is already two p.m. and the sky is downright dark by the time they reach the last peak. Hervé hadn’t lied; the dry lake is astounding, a perfect oval crater more than a kilometer long. It is entirely empty, its sides lined with concentric curves left by the receding water, like the half‐moons of giant fingernails. There is no water left at all. A strange siphoning phenomenon had caused the lake to empty underneath a rocky barrier. In the old basin nothing remains but gigantic pieces of ice, some of them several dozens of meters high—a testament to the time when they were all one structure, with a glacier below them. How long had they been there, crammed side by side like a forgotten army? Under the now‐gray sky, the monoliths, speckled with old dust, give off an air of poignant melancholy. Louise pleads once again for them to turn around.

“We know where we are, we’ll be able to come back. It’s not worth getting soaked …”

But Ludovic is already hurtling down the slope, whooping with pleasure.

They wander for a bit through the chunks of ice. Close up, the ice seems sinister. The whites and blues, ordinarily dazzling, are stained with dirt. Some of it is slowly melting, tarnishing the surface and giving it the look of a piece of parchment devoured by insects. Nevertheless, Ludovic and Louise are captivated by the ice’s gloomy beauty. Sliding their hands over the worn‐out cavities and caressing the cold exteriors, they muse that the ice melting before their very eyes existed well before them, well before Homo sapiens started to turn the entire planet upside down. They start whispering, as though they’re in a cathedral, as though their voices threaten to upset the fragile balance.

The rain beginning to fall interrupts their contemplation.

“Look, this ice isn’t in great condition. Hervé may have had fun climbing on it, but honestly, I don’t see the point. It would be much better for us to hurry back. The wind is picking up and that might be tough for the dinghy’s little motor.”

Louise is no longer just grumbling; she has switched to issuing commands. Ludovic knows this tone of voice is not to be questioned. He also knows that she often has good intuition and judgment. All right, they’ll turn around.

They climb back up the crater and run down the slope toward the valley. Their jackets are already flapping in the breeze, and their feet are sliding on the damp rocks. The weather has changed rapidly. When they reach the last pass, they notice wordlessly that the bay looks nothing like the peaceful sight they had seen on the way there. An evil spirit has caused its surface to go murky with raging waves. Louise is running and Ludovic is stumbling behind her, grumbling. They arrive at the beach out of breath. The waves are crashing chaotically. In the swell that forms, they can see their boat rocking forcefully at the end of its chain.

“Well, we’ll get soaked, and then we’ll deserve some nice hot chocolate!” says Ludovic confidently. “Go in front and row right into the wave while I push. As soon as we’ve passed the breaker zone, I’ll start the motor.”

They drag the dinghy, looking for a lull in the waves. The freezing water churns around their knees.

“Now! Go! Row, for God’s sake, row!”

Ludovic is slipping in the wet sand while Louise struggles with her oar in front of him. A wave breaks, filling the little boat with water, and then another wave catches the boat askew, lifting it up and tipping it upside down as though it were nothing but a piece of straw. They find themselves thrown against each other in a whitish, seething swirl.

“Shit!”

The dinghy is already being swept away by the waves. With one hand, Ludovic catches its rope. Louise massages her shoulder.

“The outboard motor hit me in the back. It hurts.”

They are standing next to each other, dripping wet and stupefied by the sudden violence.

“Let’s drag the dinghy over to that corner of the beach, where the waves aren’t breaking as much.”

Resolutely, they haul the tiny boat to a place that seems more promising. But when they get there, it becomes clear that it’s not much better. They attempt the maneuver twice more; both times they are thrown back into a whirlpool of foam.

“Stop! We’ll never make it and I’m in too much pain.”

Louise lets herself collapse on the ground. She holds her arm, grimacing, the tears falling from her eyes invisible thanks to the rain whipping her face. Ludovic kicks the ground angrily, sending a spray of sand into the air. He is overcome with frustration and rage. This fucking place! This fucking island, fucking wind, fucking sea! If they’d been half an hour earlier—an hour, max—they would be drying themselves off in front of the stove and laughing about the whole thing right now. He is furious about his powerlessness and the sense of remorse that is painfully starting to set in.

“Okay, we won’t make it. Let’s just go find shelter in the station and let this pass. The wind picked up fast—it’ll die down soon.”

With difficulty they pull the dinghy high up onto the beach, tie it to an ancient gray pole, and start off among the remnants of planks and sheet metal.

Over the past sixty years, the wind has taken its toll on the old whaling station. Some of the buildings have been blown up from the inside, as though by an explosion. Flying rocks have broken the windows and violent winds have taken care of everything else. Other structures are leaning perilously, waiting for the final blow to finish them off. Next to the wooden ramp on which whales were dragged to be dismembered is a shed that catches Louise’s and Ludovic’s attention. But inside it smells so horrible that they gag. Four elephant seals all lying on top of each other belch noisily at the intrusion.

Annoyed, Louise and Ludovic venture farther into the ruins toward a two‐story shack that seems to be in better shape. A waddle of imperturbable penguins crosses their path, and Ludovic is tempted to chase them to make them regret their indifference. The inside of the building is gloomy, dark, and damp. The old floor tiles, metal tables, and decrepit cooking pots reveal that the room they are in must once have functioned as a shared kitchen. The room next door does in fact look like a dining hall. Louise collapses onto a bench, trembling. She’s in pain, but most of all she’s afraid. She understands a mountain’s temperament, knows how to deal with its fits of rage: at worst, you wrap yourself in a bivvy sack, burrow into the snow, and wait. But here she feels lost.

Ludovic mounts the concrete stairs. At the top he finds two vast dormitories, cubicles separated by half partitions that each contain a battered mattress, a small table, and a wide‐open wardrobe. Faded photos, a single lace‐up boot, and tattered clothing hanging from a nail give the rooms the appearance of having been hastily abandoned by men who were all too happy to escape this hell. In the back, a door hanging half off its hinges leads to a little room with wooden shiplap walls that’s furnished much more nicely: probably the bedroom of a supervisor.

“Come on, it’s better up here. We can wait in the warmth.”

“Warmth” is a generous way of putting it. They sit on the bed, which creaks underneath them. The rain slaps against the loose windowpanes, seeping in; already a pond has formed in a rotting corner of the floor. Greenish light illuminates the streaks of moisture on the whitewashed walls. The only chair is broken, and for some reason Ludovic finds himself wondering why. Only a desk with drawers, much like the kind that teachers used at the turn of the century, appears intact.

“Well, here’s our mountain refuge! Let’s take a look at your shoulder. And we have to dry ourselves off.”

He’s making an effort to speak soothingly, to give the impression that this is nothing but an adventure, but his hands are trembling lightly. He helps her undress so that they can dry her sopping‐wet clothes. Naked, her thin and muscular body appears fragile. She had always refused to sunbathe when they were in warmer climates. As a result, only her arms, face, and the bottoms of her legs are tanned, making the rest of her complexion appear even paler. Her black bangs are dripping onto her eyes, which are green with flecks of brown. Those eyes were the first thing about her that he had found irresistible, five years earlier. He’s overcome by a wave of affection.

He wrings out her clothes and rubs her body with her sweater as fast as he can to warm her up. Her left shoulder has a sizable gash—from the propeller, presumably—and a large blotch that is already turning blue. Shivering, she lets him handle her as though she were a doll. He does the same thing for himself, but soon feels the chill of the soaking‐wet clothes that are sticking to his skin. In the summer, even in good weather, it barely gets above sixty degrees here. Right now it must be somewhere around fifty degrees.

“Do we have a lighter?” he asks her.

“In the bag.”

Of course she—the alpinist—would never go anywhere without her precious lighter. He also finds two emergency blankets and quickly wraps her up in one.

Rummaging through the kitchen, he unearths some kind of large aluminum roasting pan and pulls some boards down from shelves that are falling to pieces. Taking it all back upstairs, he cuts some small slivers from the boards with his knife and uses them to light a small fire. The room fills quickly with smoke, despite the open door, but it’s better than no fire at all.

He forces himself to go outside to investigate the situation. The wind has intensified, its gusts causing the sea to appear as if it’s smoking. A solid forty knots. Not the apocalypse, but still, it will be impossible to get back to the boat. He can see it between the sheets of rain, staying valiantly upright among the waves. The cloudy gray sky has descended so low that the tops of the cliffs are no longer visible, and it is growing dark.

“Looks like we’re here for the night,” he announces when he returns from outside. “Is there anything left to eat?”

Louise has recovered a bit of energy. She’s keeping the fire going, which is comforting even though the old boards are giving off a terrible smell of tar as they burn. They hang their jackets up near the flames and huddle together, chewing on granola bars.

Neither one of them has any desire to talk about the situation. They both know it’s dangerous terrain, that to do so would force them to confront each other: Louise, the cautious one, versus Ludovic, the impetuous one. The argument will come later, when this unpleasant episode is in the past. They’ll analyze everything that happened. She’ll try to prove to him that they had been reckless, and he’ll retort that the situation had been unforeseeable; they’ll bicker and then they’ll make up. It’s become almost a ritual by now, a safety valve for their differences. Neither one will admit defeat, but both—convinced of their own rightness—will agree to bury the hatchet. For now, though, they have to stay united and wait this out.

With eyes reddened by the smoke, they dry off, surrounded by a growing cacophony. On the lower level, the wind is roaring through the abandoned rooms, a relentless low modulation punctuated by cries that grow shriller with each gust of wind. At times a brief respite sets in and they can feel their muscles relax in unison. But then the growling starts up again, seemingly even louder than before. Here and there, pieces of metal clang against each other, the sound reverberating. Louise and Ludovic stay silent, each of them engrossed in the gloomy symphony. Fatigue—from the hike, and perhaps more notably, from their emotions—comes crashing over them. Finally, Ludovic unearths a blanket that smells like old dust; the two of them curl up on the little bed and fall asleep immediately.

Ludovic awakens in the night. The sounds have changed. He deduces that the wind has shifted, and that now it is coming from the land. It has gotten even more violent. He can hear its grumbling coming from far up on the mountain, hurtling down to the valley like a drumroll before striking the building, which seems to sway from the blows. He considers the wind’s change of direction to be a good sign; the end of the storm is approaching.

Amid the darkness and the warm dampness of their entangled bodies, he experiences, briefly, a sense of calm. True, the two of them are all alone, without any other human being within a radius of thousands of kilometers, amid extreme wind. But on the other hand, they have found shelter, and later they will be able to laugh about the storm. He has the strange impression that each part of his body is autonomous, separate from the rest of it, and he takes stock of each element of this strange situation: the hollowed, battered mattress underneath his back; Louise’s slow breathing against his chest; the wind, seeming to come out of nowhere, that brushes against his head. He is tempted to wake her so that he can make love to her, but then remembers her shoulder is hurting. Better to let her sleep. Tomorrow morning, maybe …

A little before dawn, the noise suddenly stops. Half‐awake, they both realize that the storm has passed, and then fall back asleep, this time completely relaxed.

A ray of sunlight pulls Louise from her lethargy. Until the storm ended, she had been having nightmares. She dreamed that the windows in their apartment in the fifteenth arrondissement had been blasted by a monstrous wave, and that she was drifting on a raft through streets flooded with brown water, surrounded by calls of distress and arms waving desperately from the windows.

“Ludovic, are you asleep? It seems like it’s over!”

They shake out their bodies, which have grown stiff. Louise grimaces as she sits up, feeling her injured shoulder at length with her other hand.

“I don’t think it’s broken, but you’ll need to take the helm for a while.”

“Okay, princess. Let’s go. The hotel isn’t exactly the height of luxury, but breakfast will be served on board in fifteen minutes, if Madame will oblige.”

They smile at each other, collect their things, and leave the room, which has a lingering odor of cold smoke.

Outside, the sun is shining as brightly as it had the day before.

“This fucking place, huh?”

Still standing on the doorstep, they both experience the same feeling. Something seizes their stomachs in a tight grip; an acridness burns in their throats; they are overcome by an uncontrollable trembling.

The bay is empty.

“The boat … That’s not possible … It’s not there …”

They’re stammering, babbling, blinking their eyes as though it will fix the image in front of them. This must all be a bad dream. They just need to rewind the last few hours and start again, and this time everything will go as planned. Upon leaving the station, they were supposed to see the Jason still there, immobile and reassuring, and they would walk down to the shore, bantering with each other. But the reality of the situation persists cruelly. The boat has disappeared.

For a long time they scrutinize the bay, looking for a piece of debris or at least a bit of the mast peeking out from behind a cliff. But there’s nothing. Or, more accurately, there’s only life going on as usual: gulls pecking frantically at the beach, the hissing of the waves pulling back into the sea. Everything looks normal. The Jason—their boat, their home, the means of their liberty—has simply been erased, as though it were an error. But this is simply unacceptable. It can’t be.

Reeling, they are unable to exchange a single word. The horrifying consequences of their situation are sinking in. No more home. No more food. No more clothing. No way to leave the island or communicate with anyone. Once they’ve overcome their denial, it is the absurdity of the situation that overwhelms them. Ludovic has simply never for a second imagined that he could someday be without food, shelter, the essentials of life. Whenever he saw impoverished people on TV, he would fend off his pangs of conscience by convincing himself that those people probably didn’t need as much as he did—that they were used to living with less. He would sometimes send off a check to UNICEF, but he never felt particularly concerned.

Louise had often slept outside during her mountaineering trips, sometimes while soaked through from rain and with one eye open to watch for danger. Once, for three days, she had even shared rations meant for one person with three other people due to a supply miscalculation. In the middle of the wilderness, far from anything familiar, she had experienced the inherent fragility of being human. But that had been only a brief episode; nothing fundamental was at stake. With no harm done except for shadows underneath their eyes and some stomach cramps, the four climbing partners eventually made it back down into the valley, where they luxuriated in endless showers and steaks, relishing the thrill of having lived through an adventure. In the end, those types of situations just became good memories to laugh about with each other, although at least they have prepared Louise to face the unexpected. Whether by instinct or by training, she knows how to sort the essential from the superfluous and the dangerous from the disturbing. In order to become a good alpinist, she had to learn to reevaluate a goal based on the present circumstances—to turn back or keep going depending on the state of the group, the weather, and other natural conditions. She is therefore the better equipped of the two to pull them out of their lethargy:

“The dinghy, as long as it’s still there! We can use it to go look around. The Jason was halfway between the cape and the group of rocks across from it. Maybe it sunk right where it was.”

“But we would see the tip of the mast!”

Ludovic is struggling with the facts in a different way. Ordinarily he is optimistic, ready for anything, but now he feels empty. Nothing is of any use.

“It could have lost its mast. There can’t be more than seven or eight meters of water—we might find some stuff, maybe food or tools. There’s a satellite phone in the emergency dry bag. We have to at least try. Come on, let’s go!”

“No, I’m sure that it was dragging anchor. I heard it last night. The wind shifted northwest, and it accelerated as it came down from the mountains. A real katabatic wind, just like in the books.”

“I don’t give a shit about books!” she screams, tears in her eyes. “What do you want to do? Go back to the hotel?”

She takes off in a fury toward the beach and he follows her. The same thoughts are whirling around in both of their heads. The island is deserted. In fact, it’s a nature reserve that they shouldn’t have landed on in the first place. But they had both decided to break the rules:

“No one will come by anyway. It’ll be a chance to experience real nature. And it will just be a quick stop, only a couple of days, no one will ever find out …”

And it’s true: no one knows. Their friends and family back home think that they’re en route to South Africa. They’ll never look for them here. They’ll just believe them to be lost at sea. Ludovic has a fleeting vision of his parents waiting next to the telephone in their house in the Parisian suburbs. If he and Louise don’t find the boat, then this island will become a prison—a prison with no guard except thousands of kilometers of ocean.

The dinghy is still there, covered in sand and seaweed from the storm. This is a small comfort.

For an hour they row around the area where they had cast anchor. The breeze just barely skims the clear water, which is such a translucent green that they can see scattered rocks down at the bottom and a few dark masses that look like machine parts that were lost or removed from the whaling station. There’s no way they wouldn’t see a shipwreck.

Discouraged, they return to the beach.

“We didn’t use enough chain,” Louise says unhappily.

“Yes, we did. Three times the depth, just like we usually do.”

“Well, obviously there’s nothing ‘usual’ about this place!”

“Also, the Soltant anchor is the best kind. It’s supposed to hold anywhere. It certainly cost us enough.”

“Oh, then thanks so much, Monsieur Soltant. Is he the one who’s going to come find us? We should have used twice as much chain as usual. If we’d done that we wouldn’t be in this situation. And I told you yesterday that we should have turned back earlier. But no, you just wanted to have a good time; you dug your heels in and said everything would be fine, we’d just get a little wet …”

Louise’s voice is flat, full of icy rage. She is nervously rubbing her shoulder, staring at the sand, her back to Ludovic. If she were to look at him, she knows exactly what she’d see: his helpless, large, wrestler’s body, with his arms dangling at his sides and his blue eyes like those of a child whose favorite toy has just been broken. The man who’s made for the joy and carefreeness that she loves. The sight would make her burst into tears, and it’s not the right time for that.

He doesn’t want to respond to her criticism. Ever since they had turned back the day before, he has had the bitter taste of regret in his mouth. But her comments have hurt him. He has to find a solution so that she’ll forgive him. Surely he must have a solution.

“Maybe we could use the motor and sail around the bay … It could have sunk alongside a cliff.”

“You’re delusional. And even if we found it, what would we do? I don’t know how we’d get it afloat again.”

“At least we might be able to dive in, rescue some …”

Ludovic doesn’t finish his sentence. Louise is crying soundlessly. He draws her against his shoulder. How have they gotten themselves into this absurd situation? It doesn’t seem fair that they should be punished like this for a stroll that lasted a little too long. He is thirty‐four years old and the idea of death has hardly ever crossed his mind. The deaths of two of his friends—one from a motorcycle accident, one from severe pancreatic cancer—had shaken him, but they also made him all the more determined to go on this sailing trip. They had to live! Live as much as they could, before something caught up with them! And now it is a balmy day during the austral summer, and they are in the midst of a magnificent landscape, and something has caught up with them.

The duplicitous sun is making the beads of moisture sparkle like thousands of diamonds. In the distance, the plain is steaming lightly. Fur seals and elephant seals are lounging around, yawning happily. He looks around him and thinks that nothing—not a bird’s flight, nor a wave, nor a blade of grass—will change if they disappear here. The wind will quickly sweep away their footprints.

Ludovic is a quintessential millennial. He grew up in a house in the suburbs, the only son of parents who were both managers, and was given everything he could ever want, from ski trips in Alpe d’Huez and sailing trips in the Balearic Islands to video games to occupy his precious little head whenever his parents were out late. His blond hair—cut with military precision and styled with gel every morning—accentuates his six‐foot, three‐inch frame. With his blue eyes and dimpled chin, he stole the hearts of all the girls in middle school and then in high school—easy successes that he fully enjoyed.

His lack of follow‐through exasperated his teachers; a common refrain on his report cards was “Doesn’t live up to his potential.” One way or another, he managed to graduate from business school, where he had spent a lot more time drinking beer and smoking weed than attending lectures. With help from some connections of his father, he found a job as an account manager at Foyd & Partners, an event agency that could not be more French despite its name, which was supposed to sound trendy. He took to this somewhat superficial role well, thanks to a strong aptitude for happiness that drew other people to him like a magnet. Being with him made people feel good; he made life feel simple, fun, fascinating. Not only did he always see the glass half‐full, but his enthusiasm and joie de vivre were contagious without him even having to try. His attitude wasn’t a facade, or an affectation; it was merely the result of a life that had been protected and happy. He couldn’t remember ever having woken up feeling sad, or even slightly melancholy. Little by little, he had come to recognize that this was an unusual ability, but he didn’t take particular pride in it. Giving some of his surplus of joy to the people around him was just his nature, his way of contributing to the world. People said that he was a truly nice person.

Louise, at first sight, seems conventional, almost old-fashioned, with a slender frame, an elongated face, and the quick, often forced smile of someone who is trying not to offend. She is the daughter of shopkeepers from Grenoble who still budget carefully despite their financial security; growing up, she didn’t want for anything, either, except perhaps some attention. Her two older brothers were the pride and joy of the family, while she, “the little one,” slipped through the cracks. Her thoughts, dreams, and academic and personal achievements were never of much interest to her family.

The way she looks reflects the lack of attention she received. Even she thinks so. Five foot one, dark‐haired, and bony, she has long despaired over her nonexistent breasts. She had gone through childhood and adolescence without attracting much notice, but she seemed to be okay with this, as though she were seeking forgiveness for her own existence. People said that she was uncomplicated, although this wasn’t true. She graduated from high school, studied law in Lyon, took the civil service entrance exam, and found a position in a tax office in Paris’s fifteenth arrondissement. During all this time she continued to suffer from a sort of transparency.