Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

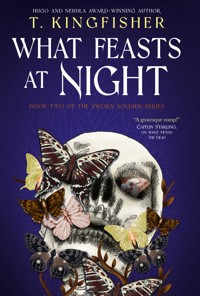

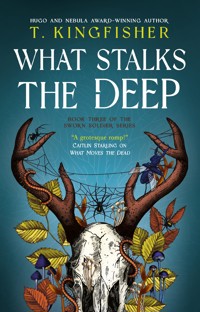

The next novella in the New York Times bestselling Sworn Soldier series, featuring Alex Easton investigating the dark, mysterious depths of a coal mine in America, from Hugo and Nebula Award-winning author T. Kingfisher. Perfect for fans of Silvia Moreno-Garcia and Stephen Graham Jones. Alex Easton does not want to visit America. They particularly do not want to visit an abandoned coal mine in West Virginia with a reputation for being haunted. But when their old friend Dr. Denton summons them to help find his lost cousin—who went missing in that very mine—well, sometimes a sworn soldier has to do what a sworn soldier has to do...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 214

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Praise for The Sworn Soldier Series

Also by T. Kingfisher and Available from Titan Books

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Praise for

THE SWORN SOLDIER SERIES

“A gothic delight!”

LUCY A. SNYDER, author of Sister, Maiden, Monster

“A deeply unsettling examination of what sometimes goes on behind polite smiles and courteous speech.”

CASSANDRA KHAW, author of Nothing But Blackened Teeth

“A grotesque romp! It takes up residence beneath your skin and refuses to leave.”

CAITLIN STARLING, USA Today bestselling author of The Death of Jane Lawrence

“T. Kingfisher spins biting wit, charm and terror into a tale that will make your skin crawl. Poe would be proud!”

BROM, author of Slewfoot

“Creepy, claustrophobic, and completely entertaining, What Moves the Dead left me delightfully repulsed. I adored this book!”

ERIN A. CRAIG, New York Times bestselling author of House of Salt and Sorrows

“Perfectly hair-raising in all the right ways.”

PREMEE MOHAMED, Hugo and Nebula Award-nominated author of The Butcher of the Forest

“Dissects the heart of Poe’s most famous tale and finds a wholly new mythology beating inside it . . . Pure fun.”

ANDY DAVIDSON, author of The Boatman’s Daughter

Also by T. Kingfisherand available from Titan Books

The Twisted Ones

The Hollow Places

Nettle & Bone

A House with Good Bones

Thornhedge

A Sorceress Comes to Call

THE SWORN SOLDIER SERIES

What Moves the Dead

What Feasts at Night

THE CLOCKTAUR WAR DUOLOGY

Clockwork Boys

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

What Stalks the Deep

Print edition ISBN: 9781803369716

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803369723

Broken Binding edition ISBN: 9781835416938

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: September 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© T. Kingfisher 2025

T. Kingfisher asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

EU RP (for authorities only)eucomply OÜ, Pärnu mnt. 139b-14, 11317 Tallinn, [email protected], +3375690241

To Cousin Amy

1

So this was America. Fresh off the war with Spain, which was all that anybody was talking about. Guam. Everyone on the ship over had been full of opinions about Guam. Several people asked my opinion “as a military man.” They were wrong about the man part, but the thought of explaining Gallacia’s sworn soldiers to a boatload of Americans was so exhausting that I needed a gin and tonic just to contemplate it, and a second one to decide that explaining would be a bad idea.

As for Guam, my opinion was that it was probably a fine place and the weather was undoubtedly better than in Gallacia. I developed the habit of smiling down into my gin and tonic and saying that I had never been to Guam, and so wouldn’t presume to know more than the people on the ground there. This had the advantage of being true, and also generally made at least one other person in the conversation look like an absolute tit.

And if I passed our days at sea having gin and tonics and no opinions about Guam, that meant I was definitely not worrying about the telegram that I had been sent by my American friend, Dr. James Denton.

BEGGING YOU TO COME WITH ALL HASTE STOP NEED YOUR HELP STOP BRING ANGUS STOP

If it had been anyone other than Denton, I would have sent back another telegram to the effect of “What the devil is the problem stop?” but Denton and I had faced down horrors together two years prior, and I knew that he had a cool head and was, if anything, far more skeptical than I was. If he thought he needed my help, then I would damn well come and help him. Also, he included two tickets to Boston.

(Also, my sister was going to have another child and while I think babies are fine in the abstract, my sister has a regrettable belief that if I just hold one long enough, I will come to enjoy it. I will not. I have proven this to my own satisfaction, but apparently not to hers, and America seemed like an excellent alternative. Land of opportunity, they say, which presumably includes the opportunity not to hold a baby.)

I say this all very flippantly, but I’ll be honest, I didn’t much care for the telegram. Not that I objected to Denton asking for my help—far from it. There are some experiences that bond people together more closely than blood, and the nightmare we’d faced had been one of them. If he needed my help, I’d come.

No, what bothered me was the idea that whatever trouble Denton was in, it was the sort of trouble that required Angus and me to cross an ocean. As if, given the entire North American continent to draw from, Denton needed the two people he knew with experience in nightmares.

I tried not to dwell on it, and instead lost myself in listening to people be wrong about Guam. It almost worked.

Our ship steamed into Boston on a brisk October morning. The sun was shining, the water was relatively calm for the season, and the air smelled only slightly of brine and dead fish. Our crossing had been uneventful, our docking equally so. The jaws of the wharf closed over our ship and held it fast. The streets of Boston looked like the streets of any other port town I’ve encountered. It could have been London or Hamburg. Make half the people darker and half the walls lighter, and you could be in Barcelona or Istanbul. Skin and stone changes, but not much else does. There are always children pelting around and harried-looking men moving cargo into wagons and a few extremely worried men who do not have cargo and don’t know why and a dozen horses looking bored and one horse looking like it is about to go on a rampage and a couple of lost passengers huddled together like a clutch of baby chicks. Inevitably, a vendor is trying to sell something to one or more of these groups, except possibly the horses.

The familiarity was oddly comforting. In general I rather like Americans—they’re usually so terribly earnest—but I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t a bit nervous. One American can really fill a room. I assume it only takes a hundred or so to really fill a country.

A man threaded his way through this mess, avoiding the vendor, and approached us. He was fine-boned and neatly dressed, like a small bird wearing a clean, unassuming suit.

“You must be Lieutenant Easton,” he said, shaking first my hand and then Angus’s. “I’m Kent, Dr. Denton’s assistant. I’m to see you to the hotel where you’ll be meeting him and Mr. Ingold.”

“Lead on, then,” I said, trading a look with Angus. We don’t shake hands in Gallacia, but Americans are completely mad for it, and you can’t refuse or they get this confused, somewhat hurt look. I resigned myself to shaking a great many hands in the next few weeks.

Kent secured a cab. Angus and I hefted our luggage onto the roof. “Is that all?” asked Kent. “No more trunks? No equipment?”

“We travel light,” I said, wondering what sort of equipment he expected me to bring. Angus had the rifle case. Did that count as equipment? Or did he think that all Europeans were like the upper-class Brits, and had five different outfits for each meal of the day?

(Come to think of it, maybe Americans did that, too. If so, thank God I’d brought one of my dress uniforms. You can always get away with wearing a dress uniform instead of formalwear. Although Denton had never struck me as a formalwear type. Someone who would help you finish off a fungal abomination that had taken over your childhood friend, yes. Someone who wore a tuxedo with tails to dinner, not so much.)

Our cab left the docks, trotting past rows of horse-drawn streetcars. We don’t have those in Gallacia. Then again, we don’t have that much flat ground in Gallacia. It is a very small country made of very large mountains. We grow turnips and sheep, but our primary export is people who want to get the hell away from it.

I was farther away now than I’d ever been. “I don’t suppose you’d care to tell me what this is all about?” I asked Kent.

Kent folded his hands neatly on his knee. “I am certain that Dr. Denton will explain everything when you arrive.”

So much for that. Angus might have been able to get more out of him, if they’d been alone and doing the “Oh yeah? Well, my boss once made me carry kan ten miles in the snow because ka was too cheap to hire a horse!” dance, but it didn’t look like we’d have time.

We eventually reached a medium-sized hotel. Kent paid the driver and helped Angus pull down the luggage, and we followed him inside.

“That is a lot of mauve,” I said, after a moment of stunned silence. The wallpaper was mauve, the carpet that stretched across the marble floor was mauve, the draperies were mauve, the upholstery was mauve, and the pillows scattered on the furniture were mauve with gold tassels. I suddenly knew how a bee must feel with its head buried in a mallow flower.

Kent waved to the front desk and a man came out from behind it, wearing a mauve tie. He shook our hands and said that it was the hotel’s great pleasure to serve us. He clapped his hands and summoned a bellhop, dressed from head to toe in mauve, who took our luggage. I wondered if the bellhops ever stood up against the walls for camouflage.

The hotel man shook our hands again and pressed our keys into them at the same time, in a skilled maneuver that I assume required years of experience. “Dr. Denton is waiting for you in the dining room,” said Kent, herding us efficiently to one side of the lobby. We entered the dining room, which had mauve tablecloths, and I spotted my old friend Denton, who, thank Christ, was wearing a dark brown suit and no mauve at all.

He rose to his feet and shook our hands. “Easton. Angus. I’m so glad you agreed to come.”

“From the tone of your telegram, I expected you to be hip-deep in live wasps,” I said, “not dining at such a . . . ah . . . colorful establishment.”

“We’ll get to the wasps in a moment,” said Denton. “May I introduce my friend, Mr. John Ingold? John, this is Lieutenant Alex Easton and Angus . . . ah . . . forgive me, it occurs to me that I don’t actually know your full name.”

“No one does,” said Angus gruffly.

I hid a smile. Angus has been with me since I was a scrawny fourteen-year-old with a shaved head and bound breasts who barely knew which end to hold a gun by. In all that time, I had never learned if Angus was his first or last name or where he came from originally. If he ever wants me to know, I imagine he’ll tell me.

“Pleasure to meet you both,” said John Ingold, reaching across the table to shake our hands. He had the tan skin and straight black hair that I associate with the native people of the continent, and when he opened his mouth, his Boston accent was so thick that you could stand a spoon up in it. (Yes, we know about Boston accents in Gallacia. We’re backward, but we do occasionally meet people.)

(Okay, fine, I met a Bostonian in Paris once.)

The waiter approached. I half expected him to go in for a handshake as well, but he merely asked for our orders, then retreated into the mauve distance.

“So,” I said, putting my elbows on the table and looking at Denton. “What has you so concerned?”

Denton rubbed his face. “It’s a mess,” he said.

“Dark doings,” Ingold added. The way he pronounced dark as dahhhk was so pure that I had an involuntary urge to snatch up the teapot and find a harbor to dump it in.

“My cousin Oscar’s gone missing,” said Denton. “We grew up together, and we were in very regular correspondence until his letters stopped three weeks ago. I sent an additional two letters, and then went to West Virginia myself to try to find him.”

I settled back against the exceedingly mauve cushions. “I’m sorry to hear it, but you must know, Denton, that I’m no kind of detective.”

“No, of course not.” Denton shook his head. “I know exactly where he vanished. He was investigating an abandoned coal mine outside of Shaversville. That’s what I need you to help me with.”

“I’ve never been in a coal mine in my life,” I protested.

“I have,” said Angus. “In Limburg. Was dark as the pit and we had to walk bent over.”

We all waited politely for him to say anything more, but this seemed to have exhausted Angus’s store of coal mine information. Denton coughed. “At any rate, it’s your experience with . . . unusual . . . circumstances that I need.”

I raised an eyebrow. Angus raised both of his. “You mean like what we saw at Usher’s lake,” I said flatly. “Because I’ll tell you, that was the first time I’ve dealt with anything like that.” (Sadly it was not the last, but what had happened a year ago in Gallacia was not something I wanted to dwell on.)

“The first time for me, too,” said Denton. He looked suddenly weary and much older than I remembered. “But you did deal with it, and you know there are terrible things in the earth. If you encounter another one, you won’t waste time insisting that there must be a different explanation or that I’m lying to you or that none of this can possibly be happening.”

Terrible things in the earth. Yes. Denton and I had seen a terrible thing in the earth and ended it, with the help of Angus and a brilliant Englishwoman who knew everything worth knowing about mushrooms. The only reason that I slept at night was because we had destroyed it. I did not want there to be another one.

“Another fungus?” I asked sharply.

Denton drank down his whiskey and signaled for another one. Ingold watched me, his arms folded, and I wondered how much Denton had told him about what we saw in the tarn.

“Not a fungus,” Denton said, when the waiter had left again. “At least, I don’t think so. But more lights in the deep.”

2

“About two months ago, my cousin Oscar went to Hollow Elk Mine in West Virginia,” Denton said, “looking to see if there was any coal left.”

I sipped my gin and tonic and waited. His mention of lights in the deep had taken me back, forcibly, to Usher’s lake, to the brilliant, terrible stars that glowed in the depths of the tarn. It was not a memory I cherished.

“Everything here runs on coal,” Ingold explained. “During the War Between the States, the South ran their warships on coal from the Carolinas. The North ramped up production in West Virginia to compensate, and never stopped. Now you’ll hardly find a hillside that somebody’s not sinking a mine into.”

“But this one was abandoned?” I asked.

Ingold nodded. “Hollow Elk Mine is a bit east of Shaversville, dug in the 1700s. Old place, but the ground was bad. Rockfalls, cave-ins, the lot. Miners said it was unlucky.”

“Some of them said it was haunted,” put in Denton.

“Any unlucky mine is haunted,” said Ingold dismissively. “You kill enough men with bad food and bad air, the earth soaks that up. What my mother’s people would call bad medicine. I doubt Hollow Elk is worse than any other in that regard. No, there was more at work here. Miners reported strange lights in the deep, not just the usual knocking and tapping one gets in a working mine. It was abandoned about forty years later. The owners couldn’t get enough people to work it, and by the end they were losing money on it. It reopened briefly during the war, but closed right up again.”

“Who are the owners now?” asked Angus.

“You’re looking at him,” said Denton. He leaned back with a sigh. “Oscar, God love him, always liked digging, whether it was papers or actual dirt. He was going through our family’s old papers when he found the deed to the mine. I hadn’t even known I’d inherited it. No one’s given it any thought for at least a generation, I imagine. Hollow Elk had been abandoned, and hadn’t been worth much even when fully up and running, according to the papers. Oscar was curious as to why it had been abandoned.” Denton took a gulp of whiskey. If I didn’t know better, I’d think his eyes were getting misty, which was surprising, because Denton was not a misty-eyed type.

“When Oscar and I were kids, he was always looking for caves. Got stuck in one when he was twelve and it took the fire department three hours to get him out again. Then he was back in there the next week. So when he asked if I’d mind if he took a look at the old mine, I didn’t think twice. He said he wanted to see if there was any money to be made from it, with more modern mining techniques, but I knew mostly he just wanted an excuse to go poking around underground. Caves, mines, that sort of thing—he was mad for them.” Denton looked up at me, a wry, unhappy twist to his lips. “So you see, this is ultimately my fault.”

I raised a skeptical eyebrow at that. “Did he have experience underground?” Angus asked. “Other than getting stuck?”

“Quite a lot, yes.”

Angus and I exchanged a look. “Then I don’t see how you could be blamed, unless there’s a lot more to the story,” I said.

The line between Denton’s eyes didn’t smooth out. “He sent me a number of letters,” he said. “The first few aren’t particularly noteworthy. He reached the mine, set up camp there, and began mapping out the details. Then, almost a month after he arrived, he sent me this.” Denton nodded to Kent, who extracted a sheaf of notes from his valise and handed them to me.

I unfolded the letter. It was written in a neat, even hand, the sort of lettering beloved of clerks and teachers.

James—

I must apologize for what I am about to commit to paper, for it must seem as if I am springing it upon youwithout warning. In truth, I have been observing these phenomena since the very beginning of my exploration of Hollow Elk, but I have been reluctant to mention them. They were easily dismissed at first as the tricks a man’s mind plays on him in the dark, and I did dismiss them as such, until the evidence began to weigh too heavily against it.

Ah, I thought. The sort of person who talks about “observing phenomena.” I actually quite like people like that, because if you can get them talking about their particular specialty, they will tell you the most fascinating anecdotes about botflies or ball lightning or things they have extracted from some unfortunate soul’s rectum. They can be immense fun at otherwise stuffy parties.

I have been hearing sounds in the mine. Not the creaks or knocks that are common to mines, but peculiar sounds, as of something moving around within it. The mine entrance is large and the boards did not cover it completely, so I was not surprised by this either, suspecting only that some animal had taken up residence within. But of late the sounds have gotten closer, and there is something damnably odd about them. They are wet sounds, almost a squelching. Roger hears them too, so I have at least that much proof that it is not my imagination.

Furthermore, things have been going missing. Sheets of paper and at least two fountain pens have vanished, as well as several tins of stew. Roger denies taking any of it, and certainly he is not a man to steal paper and pen. Indeed, I should be overjoyed to find a newfound tendency to literacy in him, and would happily gift him entire reams! (I do suspect him in the case of the stew. He has lately acquired an enormous mutt from the nearby town, and I have no doubt that it eats like a horse. I do not begrudge the dog the stew, though, as it is a comfort to have a watchdog about.)

Ordinarily I would not trouble you with such minor matters, as the noises have continued off and on for weeks, and may be nothing more disconcerting than a drip behind a wall, or a frog having taken up residence in some flooded subsection, and of course, things go missing everywhere, most particularly pens. But yesterday, while I was mapping the lowest area in the third level—the last area excavated before the mine was abandoned—I saw something impossible in the depths. I saw light.

I cannot explain to you how unsettling it was. When you are deep underground, light can only mean other people. There was no possibility of a shaft from above intersecting with this one. This level was not ventilated before being abandoned. Furthermore, the light was red. Deep red, like a darkroom light. I had turned off my owncarbide headlamp to refill it, and at first I thought my eyes were playing tricks on me, but there was indeed a red light much farther down the tunnel. It did not flicker like firelight, but was strong and steady.

I am not one of those men who carries a pistol wherever he goes, certainly not within a cave system. But I tell you, James, I wished that I had one then. There was something desperately frightening about seeing a light underground where no light should be. I thought of a dozen improbable explanations, mostly involving lava—you’ll laugh at that, and I would too—but I could think of nothing that could realistically explain such a light.

Very likely I should have gone to fetch Roger to explore the tunnel with me. But at the time, all I could think was that if I did not go at once, whoever made the light could follow me up the sloping shaft to the higher levels, lie in wait there, and then come down behind me the next time I ventured in. I could not bear the thought, and so I redonned my carbide lamp and went forward toward the light.

I will spare you suspense. I did not find the source. It went out almost as soon as my own light went on. The main tunnel here splits into three passages, and I picked the wrong one initially, only to reach a dead end. The central tunnel ends in a squeeze and I would have had to crawl through on hands and knees in order to continue. I am nearly certain, however, that the red light was on the far side of the squeeze. When I turned my own light off again and waited, I heard something moving down there. It dislodged dirt and pebbles, whatever it was, and I do not think that it was the sound of further subsidence.

I would think that it was an animal, but animals do not wear lights.

At any rate, James, you doubtless think that I have gone off my head from bad air now, and I cannot say that I blame you. Certainly Roger is skeptical, although he is too loyal to say anything of the sort, and the dog he’s acquired has given no indication of any strangers about. The brute even barks at passing deer and rabbits, so I doubt any human could pass unmarked. Nevertheless, I plan to get to the bottom of this. The squeeze is a small one, as blasting on this level was not far advanced, and while the air is hardly pleasant, it is not so bad as to make one hallucinate. No, I think some person has taken up residence in the mine itself. I plan to investigate further, if it is possible to do so without the ceiling falling in on me. Rest assured that I will take all due precautions, and shall update you as I can.

Yr devoted cousin,Oscar