Sylvia Cohn (1904 - 1942) E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

This collection of poems, letters and texts was published in 2004 to mark the 100th birthday of the German writer and poet Sylvia Cohn (1904 - 1942). Sylvia Cohn did not live to see her works published; her death in the Auschwitz death camp shattered all her plans and hopes. This lyrical anthology, edited by her daughter Eva Mendelsson née Cohn, preserves the memory of Sylvia Cohn and her work in perpetuity.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 135

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

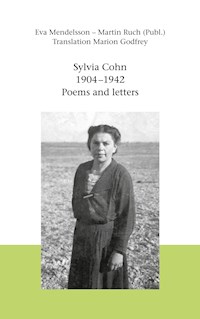

Frontpicture: Sylvia Cohn in the French camp at Rivesaltes. The last photo, 1941

Eva Mendelsson (England), youngest daughter of Sylvia Cohn. In October 1940, at the age of 9, Eva was deported to Gurs concentration camp in France with her mother and sister. From there, the two children were rescued and escaped to Switzerland.

Ursula Flügler (Offenburg), Latin and German teacher till 2002. 1978 book of poems "Erstes Lateinbuch". Collaboration on books, publications in journals.

Martin Ruch (Offenburg), freelance publicist on regional and cultural history topics, including the history of Offenburg's Jews.

Marion Godfrey, translator, London, daughter of German refugees, Civilisation Française and Philosophy graduate, has translated many books in a long career in translation and interpreting.

Content

Foreword by Eva Mendelsson

Introduction

Biography

On the poems of Sylvia Cohn

Early poems 1919–1933

Poems 1933–1940

Poems 1940–1942

Selected letters

Plays

Bibliography

Foreword by Eva Mendelsson

By the time I was 12 years old, the Nazis had scattered my family all over Europe. My sister Myriam and I were in Creuse, France. My sister Esther was in Munich, Germany. My father was in Deal, England and my mother was in a German detention camp in Rivesaltes, France.

I desperately longed for her and I wrote to her about my need. In return, she sent me the only possession she had: these poems she had written.

My mother was murdered six months later, but these poems had served me over the last 80 years as ethical guidance and proof of her unquestionable love for me.

May her memory be for a blessing.

Introduction

"A rosy glow in the firmament portends an end to the suffering” The lyrical work of the Offenburg writer Sylvia Cohn ends in March 1942 with this strong image of hope. In another poem at the time, she had written "No, our God does not forget us”, showing the strength she drew from her faith. The spectrum of her poems is clear evidence that this faith had grown even stronger since 1933. However the hope to an end of the horror is in vain and on 30 September 1942, Sylvia Cohn died in Auschwitz of "a sudden heart attack”. The death certificate signed by concentration camp doctor, Johann Kremer, is patently untrue: Sylvia did not die of natural causes.. "A rosy glow in the firmament” – this image of hope was not fulfilled for Sylvia Cohn.

In the Rivesaltes camp in the south of France, Sylvia took courage once again. Even two years after the brutal deportation from Offenburg, she was determined not to give up, despite the depression and despair all around. "Be strong in my heart and have patience” was another appeal from Sylvia, who by now was suffering from heart disease and asthma. The two children, Eva and Myriam, who had been deported with her, were sent to live in a French children's home, where they were able to attend school, and that at least was some small consolation. Eldest daughter, Esther, had stayed in Munich and found a good home in the Antonienstrasse. Sylvia only rarely had news of her, but she was reassured. Occasionally, letters were still being sent from England, where her husband Eduard had been able to emigrate and was trying to bring over his family as quickly as possible. However, the outbreak of war in 1939 had frustrated these plans. Sylvia was alone and suffering: "I am a prisoner and alone.” Almost all the necessary papers for leaving via Portugal were available in Rivesaltes, just one document was still missing ...

Sylvia Cohn had been writing poems and other lyrical works since she was very young. What remains of these is in the possession of her youngest daughter, Eva. The collection, which also includes letters, is very extensive. For the present anthology, the works giving voice to the poet's essential themes have been selected from this comprehensive body of work.

Our intention as editors was to return a Jewish poet and her work to the city of Offenburg. Especially in the years from about 1930 onwards, the lyrical expressiveness and powerful imagery of the texts is striking. These poems and letters document the life of a Jewish woman from the state of Baden in Germany and reflect her life with the family and her life in the community and the state under increasingly horrific and brutal conditions. A whole life is presented here in lyric poetry in its private and its political-public perspectives. It is a unique work and is important as a poetic as well as a contemporary historical document.

A further motivation for publication of these poems was prompted by a request from deceased philosopher and rabbi, Emil Fackenheim. Born in Halle in 1916, he was able to escape the Holocaust to Scotland and died in Jerusalem in 2003. The German weekly magazine "Die Zeit” calls him "the most important Jewish thinker of the present”. Emil Fackenheim added a 614th to the 613 mitzvot (commandments in the Jewish faith): Hitler should under no circumstances be rewarded with a retrospective victory, and that all evidence, traces and testimonies of those murdered must be collected and preserved in order to save them from total extermination. In this vein, Sylvia Cohn's poems will now also be collected and preserved for the future. Her voice was not silenced in Auschwitz. Hitler did not win.

Martin Ruch

Biography

The Jewish community of Offenburg had reached its peak with about 500 members around 1900, since when their number had been steadily declining. When the Nazis came to power, Offenburg still had about 300 Jews, of whom a hundred had been murdered by 1945. The others managed to escape. By 1945, there was no longer a Jewish community in Offenburg.

Sylvia Oberbrunner, 1916

Sylvia Oberbrunner was born in Offenburg on 5 May 1904. Her father, Eduard Elias Oberbrunner (1860–1932) was a wine wholesaler and distiller of spirits. As a respected citizen and local councillor, he was also active in the young Jewish community (in 1862 the complete civic equality of those of Israelitic faith had become law in the State of Baden) as an officer of the synagogue and longterm chairman of the synagogue. He was married to Emma Kahn (1865–1922), whose father Moritz Kahn was also a wine merchant and Eduard Oberbrunner subsequently took over his father in law's business.

The couple had five daughters: Irma (1886, married Wetzlar), Brunhilde (1887, married Lipper), Elise (1888, married Wetzlar), Martha (1890), and as a late child, Sylvia (1904, married Cohn).

Sylvia wrote her first poems while she was still at school in Offenburg. The family had its business premises and a flat at Wilhelmstraße 15. Her parents and a large circle of friends, including her teacher, Professor Stark, encouraged her in her writing. Sylvia remained on friendly terms in contact with the professor and his family for many years. Some letters bear witness to this. For example, in 1918, the teacher wrote: "My dear student, I thank you very much for the beautiful lines that brought me great joy: I look forward to working with you soon.” Perhaps that was when Sylvia had sent her revered professor her lyrical fairy tale: "What the lily told the myrtle tree in the quiet place” and in fact, she had dedicated the poem to him. Other youthful lyrical fairy tales are a "A birthday tale” and "Children and flowers”. The magic of innocence permeates this enchanted world of childhood and youth.

Wedding of Sylvia Oberbrunner and Eduard Cohn, 1925

In December 1924, Eduard Oberbrunner announced the engagement of his youngest daughter Sylvia to the merchant Eduard Cohn (1898–1976) from Schönsee in West Prussia. The son-in-law was to take over the Oberbrunner wine trading company one day. The marriage took place the following year on the bride's 21st birthday (5 May 1925). The young couple honeymooned in Italy and in her poem “Chianti”, Sylvia described this romantic journey. It is a happy time, as she confesses to her husband on 3 September, four months after the wedding: “Oh, my darling, there is so much beauty on this earth all around us and in us. For all that lives, all that is here, is a part of His great, all-encompassing divine love and only when we begin to experience it in ourselves, can we better understand the purpose of life”.

Sylvia's contribution to her school's 50th anniversary celebrations

The family grew with the arrival of children and in this next generation too, the young parents have only girls: Esther (1926–1944), Myriam (1929–1975) and Eva (1931). Perhaps the last birth in March 1931 weakened Sylvia and August finds her as a patient in the Freiburg gynaecological clinic. There she received a letter from her mother's friend, Mrs. Stärk, saying: "... that you have survived the difficult days well and are restored to full health. Yesterday evening, I waited at your home for your husband's telephone call and it was delightful to see how the little ones were interested in how their mother was doing. Esther even wanted to know what you had for dinner ...!”

In all other respects, unfortunately, daily life in Offenburg was becoming increasingly dominated by business worries. Although Eduard was busy as a salesman travelling all over Germany, in his letters to his family, the sentence "Good health when business is bad ...” appeared more and more frequently, and less and less frequently, he wrote: "Business was good today, after rain comes sunshine.” The shortage of money was also mentioned, for instance, on his birthday in 1932, when he had to be away from home on a trip once again. By way of exception, Eduard says he will call Offenburg, but under no circumstances should Sylvia buy him anything, because: "If you spend money, I'll get angry and won't call!”

Eduard wrote regularly when he was on the road and participated in family life as a loving father. In January 1926, he wrote from Donaueschingen: "Darling, I'll drink a toast with you and drink to your health and to us!” And he went on to remind Sylvia of their honeymoon trip to Laurana, saying: "... we should celebrate those memories, look back over those wonderful times and hope for even more wonderful times in the future!”

In June 1934, he wrote anxiously from the Hotel Luisenhof in Hanover: "So, you poor devils, all of you are hurt? You should be more careful. How can anyone fall out of a hammock? Have you ever seen the rope break when I lie in it? Or have you been swinging in it?”

He never forgot the children in his letters and all of them received loving cards, sometimes one to all three addressed to: "The home of the 3 Cohn girls, Wilhelmstrasse 15.”

Occasional breaks in the Black Forest show us that Sylvia sometimes found the burden of the children and the household difficult. Maybe this is why she stayed in Uehlingen (Black Forest) in 1930. The poems written at that time show us that she is anxious. In the poem “Gebet - A Prayer” she writes as early as January 1928 that she is “plagued by melancholy” and in 1939, she writes of her “sorrowful soul” in a letter to her sister Hilde. Her friend Gertrud Moritz tries to cheer her up: “You have a good husband and two dear children who need you. A mother should never be anxious or desperate.”

Poem created on the occasion of a concert circa 1930

In 1931, the parents are hit hard: their eldest daughter Esther falls ill with polio. For months, she lies in hospital in Karlsruhe. She survives, but the consequences of the disease are irreversible and as a result, Esther will subsequently have to wear leg callipers.

Poems and letters 1933-1940: we share a common burden

“No, it is not beautiful here under the sign of the swastika, as you can imagine. Where do we go from here? No, I can tell you, it feels very much like the "calm before the storm” ...and there have already been a few rumblings of an imminent thunderstorm,” she wrote to Gertrud Moritz on 1 March 1933.

The poems that are now being written clearly show the traces of these first forebodings of the thunderstorm to come. At the beginning of that fateful year, 1933, an immediate preoccupation with Jewish themes sets in. Sylvia's poems are now defined by outrage at the National Socialists' racial policies on the one hand and solidarity and hope for emigration on the other. Infuriated, she registered, for example, the increasing discrimination of the Jewish soldiers who had fought for the Kaiser and the Reich in the First World War: "Is this why you went through the war, so that people would make fun of your nose today? As early as September 1933, she speaks of Eretz Israel as the true home of all Jews: "Take us in, do not reject us!” Yet it is difficult for her to let go of her love for her German homeland, the Black Forest.

Since Jewish artists were denied access to cultural establishments and organisations from 1933 onwards, they founded a nationwide Kulturbund Deutscher Juden – the German Jewish Cultural Association. By 1935, there were more than 36 regional or local cultural associations with about 70,000 members in 100 towns and cities. Artists, actors and painters, poets and craftsmen, singers and musicians performed in Jewish cultural centres and synagogues and ensured an active cultural life. Sylvia Cohn was also involved in the Kulturbund and she participated in a competition in March 1935 with her stage play "Esther” (also performed in Offenburg), which was well received.1

Sylvia was becoming increasingly involved in social work for the Offenburg congregation: "On Sunday, 17 January 1937, at 9 o'clock in the morning, the congregation council was called to a meeting. (...) On the same day, at 3 o'clock, the general assembly of the Israelitic Women's Association took place in the synagogue hall. (...) Mrs Neu was elected as the first chairwoman and secretary. Mrs Sylvia Cohn, Paula Kahn and Irene Lederer were newly elected to the Board. After the general assembly, we enjoyed a congenial get-together over coffee and cake.”2

She wrote pieces for synagogue events, performing some of them herself, as the following minutes testify: "At 8 o'clock in the evening of 24 January 1937, members of the congregation were invited to a lecture in the synagogue hall. Our local writer, Mrs Sylvia Cohn, read from her own poems, entitled 'Of yesterday and today'. These are poems about her experiences in the landscape, about home and love, as well as poems set in the context of the times. The third part of the performance, 'Ahasver' – Ahazuerus – a stage play in 10 scenes, resonated particularly well and received enthusiastic applause from the audience. Teacher Bar, who opened the evening with a welcome address, was able to close the proceedings with praise and thanks to the author, Mrs Cohn.”3

At this time, Eduard Cohn was chairman of the local Zionist group in Offenburg. Sylvia also felt increasingly attracted to Zionism, which is probably why she was the sole representative of the Offenburg group to attend the 20th Zionist Congress in Zurich. On August 9 1937, Sylvia sent a card from the Hotel Bellerive au Lac in Zurich to her husband: "To the Board of the Z.O.G. Zionist group) Offenburg ... Dear Ed” However, she writes somewhat enigmatically: "This is the miracle of Loch Ness. / In truth I wasn't attending a congress, / this card my thoughts are defining / as I sit here incognito dining. / When I come home I will have much to say / Of the dramatic events and interesting word play! Warmest kisses, Yours, Sylvia.”

Vocabulary notebook: Sylvia Cohn was learning Hebrew in preparation for emigration

She found moving words for everyday life under the oppressive special laws of the Nazis in the poem "Fruhling 1938 für Großstadtjuden” – Spring 1938 for city Jews: "They still pretend it is yesterday / Play with the dog, go for coffee today / All my brothers and sisters of the same strain / Sharing a common burden of pain.

In the early morning of 10 November 1938, the night of "Reichskristallnacht” or crystal night, a name too pretty for the terrible events of that night, Eduard Cohn was arrested and taken to prison with the other Jewish men of Offenburg. That