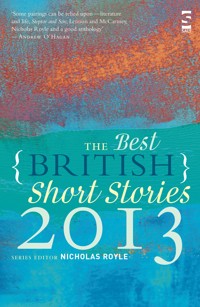

The Best British Short Stories 2013 E-Book

Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Best British Short Stories

- Sprache: Englisch

The third in a series of annual anthologies, The Best British Short Stories 2013 reprints the cream of short fiction, by British writers, first published in 2012. These stories appeared in magazines from the Edinburgh Review to Granta, in anthologies from various publishers, and in authors' own short story collections. They appeared online at 3:AM Magazine, Fleeting and elsewhere. This new anthology includes stories by: Charles Boyle, Regi Claire, Laura Del-Rivo, Lesley Glaister, MJ Hyland, Jackie Kay, Nina Killham, Charles Lambert, Adam Lively, Anneliese Mackintosh, Adam Marek, Alison Moore, Alex Preston, Ross Raisin, David Rose, Ellis Sharp, Robert Shearman, Nikesh Shukla, James Wall and Guy Ware.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 309

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

The third in a series of annual anthologies, The Best British Short Stories 2013 reprints the cream of short fiction, by British writers, first published in 2012. These stories appeared in magazines from the Edinburgh Review to Granta, in anthologies from various publishers, and in authors’ own short story collections. They appeared online at 3:AM Magazine, Fleeting and elsewhere.

This new anthology includes stories by: Charles Boyle, Regi Claire, Laura Del-Rivo, Lesley Glaister, MJ Hyland, Jackie Kay, Nina Killham, Charles Lambert, Adam Lively, Anneliese Mackintosh, Adam Marek, Alison Moore, Alex Preston, Ross Raisin, David Rose, Ellis Sharp, Robert Shearman, Nikesh Shukla, James Wall and Guy Ware.

Praise for The Best British Short Stories

‘If the aim of this collection is to show the scope of the short story, then it does so well ... Thought-provoking and highly recommended.’ SHELLEY MARSDEN, Irish World

‘An awesome anthology from an exciting publisher. Features some writers you know, alongside those you’ll hear more of in the future.’ Waterstone’s

‘Let’s hope this series becomes an annual fixture.’ CHRIS POWER, The Guardian

‘If you are new to short stories or are going to get only one short story collection this year then we recommend this one highly’ LoveReading

‘Royle’s (excellent) taste means that little explosions of weirdness or transcendence often erupt amid much well-observed everyday life.’ BOYD TONKIN, The Independent

The Best British Short Stories 2013

Nicholas Royle is the author of more than 100 short stories, two novellas and seven novels, most recently First Novel (Jonathan Cape). His short story collection, Mortality (Serpent’s Tail), was shortlisted for the inaugural Edge Hill Prize. He has edited sixteen anthologies of short stories, including A Book of Two Halves (Gollancz), The Time Out Book of New York Short Stories (Penguin), ’68: New Stories by Children of the Revolution (Salt) and Murmurations: An Anthology of Uncanny Stories About Birds (Two Ravens Press). A senior lecturer in creative writing at the Manchester Writing School at MMU and a judge of the Manchester Fiction Prize, he reviews fiction for the Independent and the Warwick Review. A new collection of short stories, London Labyrinth (No Exit Press), is forthcoming. He also runs Nightjar Press, publishing original short stories as signed, limited-edition chapbooks.

Also by Nicholas Royle:

NOVELS

Counterparts

Saxophone Dreams

The Matter of the Heart

The Director’s Cut

Antwerp

Regicide

First Novel

NOVELLAS

The Appetite

The Enigma of Departure

SHORT STORIES

Mortality

ANTHOLOGIES(as editor)

Darklands

Darklands2

A Book of Two Halves

The Tiger Garden: A Book of Writers’ Dreams

The Time Out Book of New York Short Stories

The Ex Files: New Stories About Old Flames

The Agony & the Ecstasy: New Writing for the World Cup

Neonlit: Time Out Book of New Writing

The Time Out Book of Paris Short Stories

Neonlit: Time Out Book of New Writing Volume2

The Time Out Book of London Short Stories Volume2

Dreams Never End

’68: New Stories From Children of the Revolution

The Best British Short Stories 2011

Murmurations: An Anthology of Uncanny Stories About Birds

The Best British Short Stories 2012

The Best British Short Stories 2013

Edited by

NICHOLAS ROYLE

CROMER

Published by Salt Publishing Ltd

12 Norwich Road, Cromer, Norfolk NR27 0AX

All rights reserved

Introduction and Selection Copyright © Nicholas Royle, 2013Individual contributions © the contributors,2013

The right of Nicholas Royle to be identified as the editor of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act1988.

This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Salt Publishing.

Salt Publishing 2013

Created by Salt Publishing Ltd

This book is sold subject to the conditions that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out,or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN 978 1 84471 975 4 electronic

In memory of John Royle (1938–2013)

Contents

Introduction

The Smell of the Slaughterhouse

The Writer

The Stormchasers

Mrs Vadnie Marlene Sevlon

When You Grow into Yourself

J Krissman in the Park

The Swimmer in the Desert

Voyage

Curtains

Doctors

Bedtime Stories For Yasmin

Canute

Dancing to Nat King Cole

My Wife the Hyena

Budapest

Just Watch Me

Hostage

Even Pretty Eyes Commit Crimes

The Tasting

Eleanor – The End Notes

Contributors’ Biographies

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Flash fiction. Was ever an uglier, more inappropriate term coined to describe a literary form? For years, it seemed, we read about and heard about short short stories, short-short stories (subtly different, presumably), very short stories, micro-fictions, flash fiction and so on. At some point ‘flash fiction’ began to take hold and it does now seem to be the most widely used term, with its own Wikipedia entry, numerous prizes (including Salt’s) and even a National Flash-Fiction Day.

I can count on the fingers of one hand the number of writers whom I have read who have published pieces of genuine merit that come in under, say, 1000 words. Lydia Davis is celebrated, with good reason; Kafka left a lot of very short, highly effective pieces. David Gaffney is, I think, one of very few contemporary British writers who have mastered the very short form. I loved his story ‘Junctions One to Four Were Never Built’, which was published in 2011, but couldn’t quite see how something so short could occupy a place in last year’s anthology alongside stories that were so much longer. Well, more fool me. Alison Moore’s irresistible ‘The Smell of the Slaughterhouse’, which opens the current volume, is not very much longer.

Flash fiction is still an awful term. It hardly implies lasting value. But then, given that a lot of so-called flash fiction is not particularly good, maybe it isn’t so inappropriate after all. Whatever term might be used to describe them, there are a few more really-rather-short stories in the current volume than in the previous two years. A careful reader might also suspect a bias this year towards experimental fiction. There was, in fact, no bias towards anything in my selection process, unless towards good writing, and good writing often involves taking risks.

The stories reprinted herein first appeared in literary magazines such as Ambit, Stand, Granta, Edinburgh Review and the Warwick Review, in online publications including Fleeting and The View From Here, and in anthologies and single-author collections.

I have considered hundreds of stories while reading for this volume. During the past year I have come across lots of good work in anthologies arising out of prizes and competitions, such as Lightship Anthology 2, Bristol Short Story Prize Anthology Volume 5 and Willesden Herald New Short Stories 6. Good stuff is coming out of universities in magazines and anthologies. Matter and The Mechanics’ Institute Review, from Sheffield Hallam University and Birkbeck College respectively, adopt the same approach as each other, filling their pages with work by a mixture of MA students and guest writers. Postgraduates from the University of Exeter produce Peninsula, a blend of new and old work, fiction, journalism and reportage. Short Fiction, from Plymouth University, attracts a range of very good writers. The Warwick Review continues to publish excellent short fiction, including, in the past year, outstanding stories by Elizabeth Stott, Alison Moore and Charles Boyle.

Stand has been going for more than 60 years and has moved around a bit; these days it’s based at the University of Leeds. If I had had a little more space I would have taken Elizabeth Baines’s story from issue 198 as well as Adam Lively’s from the issue before. Copies of two excellent independent magazines arrived from Scotland – Edinburgh Review and Gutter; if the fiction in the former just about had the edge, the look of the latter was a cut above. Also beautifully designed are Structo, a UK-based independent literary magazine, and Magpie Magazine, which celebrates ‘the new folk revolution in art, writing and music’ (issue five included a poignant short story by Claire Massey).

If, like me, you feel a little niggle at the way Granta doesn’t tell you what its pieces are – fiction or non-fiction – go on to the website where they do helpfully tell you what’s what. Boat Magazine is another expensively produced mix of fiction, journalism and photography; issue three included a good story by Lee Rourke about the changing fabric of an east London neighbourhood.

Ambit will hopefully cope with founder-editor Martin Bax’s retirement in 2013. The novelist and consultant paediatrician has been at the helm for more than fifty years. Andy Cox has been publishing quality horror, science fiction, slipstream and crime stories for two decades; his TTA Press stable of magazines includes Black Static, Interzone and Crimewave.

Three of the year’s most interesting anthologies happened to be metropolitan in flavour. There was photographer Roelof Bakker’s Still (Negative Press London), in which writers were invited to take inspiration from Bakker’s photographs of empty spaces in an abandoned Hornsey Town Hall; Acquired For Development By . . . : A Hackney Anthology (Influx Press), edited by Gary Budden and Kit Caless, with stories by Gavin James Bower and Lee Rourke, among others, and cover illustrations by Laura Oldfield Ford; and Road Stories: New Writing Inspired by Exhibition Road (Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea) edited by Mary Morris and beautifully illustrated with paper sculptures by Mandy Smith, in which the story I was most drawn to was Deborah Levy’s ‘Black Vodka’, which would reappear as the title story of the Man Booker 2012 shortlisted author’s collection from And Other Stories and then again in Comma’s The BBC International Short Story Award 2012 in which my favourite original story was Julian Gough’s inventive and entertaining ‘iHole’.

Simon Van Booy’s ‘The Menace of Mile End’ was a highlight of Red: The Waterstones Anthology, published by Waterstones (sic, ie no apostrophe. Insert sad face here) and edited by Cathy Galvin, formerly Sunday Times Magazine fiction editor who went on to run the popular and successful Short Story Salon at the Society Club. There was a lot of good original work in Unthology 3 (Unthank Books) edited by Robin Jones and Ashley Stokes, and some hard choices had to be made. The same was true of Secret Europe, a lavishly produced large-format collection by John Howard and Mark Valentine published by Exposition Internationale of Bucharest, and of new collections by David Constantine and Joel Lane, whose Where Furnaces Burn, a volume of his weird crime stories from the West Midlands that I had been looking forward to for some time, did not in any way disappoint.

What was disappointing about 2012 was, well, a couple of things really. Firstly, the fact that Prospect magazine stopped publishing original stories in its fiction slot, opting for stories extracted from forthcoming collections instead. It’s easier for the editor concerned, but it does turn the magazine (with regard to that slot only, of course) from a worthy sponsor of new writing into nothing more than a shop window for publishers. Secondly, the disappearance off my radar of London Magazine.

I have been an avid reader and collector of London Magazine since I moved to the capital in the early 1980s. It’s been around a lot longer, of course, since 1732 in fact. It was the first magazine to which I submitted my own short stories (they were politely returned by the then editor Alan Ross, a true gentleman of publishing). I watched it get picked up by Picador for a while and then get put down again. It went through editors like an underperforming football club goes through managers. Unpaid, I wrote a film column for the magazine for a year, glad of the free copy. Then the current editor, Steven O’Brien, took over and the magazine started to take on a distinct flavour with the appearance on the masthead and contents page of names like Grey Gowrie, Bruce Anderson, Peregrine Worsthorne. There was invariably room for one or more of editor O’Brien’s poems. My review copies stopped arriving – a series like The Best British Short Stories can’t do its job without the willingness of publishers to provide review copies – and my emailed requests went unanswered. I wondered if ‘special editorial advisor’ Gowrie, who resigned his Cabinet post in 1985 because it was impossible for him to live in central London on the £33,000 salary, had advised cuts. After a number of ignored pleas via a variety of media, I finally heard from an intern that the editor did not ‘feel inclined to offer a free subscription’. From the amount of champagne flowing at the magazine’s 2012 autumn party (pictures posted online) it doesn’t look as if austerity has hit particularly hard. I’m just sorry I missed Gowrie’s 17-page poem ‘The Andrians’, and even sorrier I’ve not been able to keep up with the magazine’s short stories, including, last year, two by Steven O’Brien.

Nicholas Royle

Manchester

March 2013

The Smell of the Slaughterhouse

Alison Moore

Rachel’s father opens the door and looks at her. Seeing her small suitcase, he says, ‘Is that it?’

‘I’ll go back for more,’ she says. She will go when Stan’s out. If she goes when he’s in, he will tell her that he loves her, and she doesn’t want to hear it. Or perhaps she won’t go back. She could leave it all behind and buy new clothes, new everything.

Stepping inside, she sees that she is treading something into the house. She leaves the offending shoe outside, puts the other one on the shoe rack and hangs up her coat. Her father, closing the door behind her, fetches paper towels and carpet freshener. Then he picks up her suitcase and she follows him through the floral mist to the stairs.

He carries her suitcase up to her room, puts it down on the bed and says, ‘I’ll leave you to it.’

She packed hastily but has remembered her make-up. She takes her cosmetics case into the bathroom, where she washes her hands and face with her father’s soap before reapplying her foundation, covering the bruising.

Back in her bedroom, she undresses, putting her clothes into the laundry basket and choosing something clean from her suitcase. She puts the rest of her things into the drawers and onto hangers. Her room has not changed at all. When she has finished unpacking and has put her empty suitcase under the bed, it is almost as if she has never been away.

She can hear the kettle boiling and crockery chinking in the kitchen.

Downstairs, she finds her father on his way into the dining room with a pot of tea, cups and a packet of lemon sponge fingers on a tray. Putting everything down on the table, he says, ‘Shall I be mother?’

Her mother always had a clean shirt waiting for Rachel’s father when he got in from work, ready for him to put on after his shower. He smelt heavily of his carbolic soap at teatime.

There was always a cloth on the dining table, and something home-baked. There might be some quiet jazz on the stereo. Her mother would pour the tea and ask about his day. He never really talked about it though. ‘Fine,’ he would say, or, ‘Busy.’

Her mother would say, ‘Good,’ or, ‘It’s better to be busy,’ and nothing much more would be said.

Rachel, sitting down now at the table and accepting sugar in her tea, remembers how she used to look at her father, at the well-washed hands in which he held his slice of cake and his teacup, and she would think to herself that no one would know he had just come from the abattoir.

Except that the smell of the carbolic soap with which he scrubbed himself daily, and whose reek is on her own skin now, has come to seem to her, over the years, like the smell of the slaughterhouse itself.

The Writer

Ellis Sharp

Swirled with mortality, entropy, a sense of wasting, the notion of shrinkage was still with him. The day before, he’d stepped from a northbound Bakerloo train at Oxford Circus, crossed to the Victoria Line and seen, at the end of a stump of corridor, a pair of massive eyes, a vast nose, the helium-filled grossness of a bloated mouth. The giant stared directly at him, with eyeballs the size of footballs. In their flinty blackness Doodles noted a second, more striking resemblance, to the pitiless eyes of the pug in Joshua Reynolds’ painting of George Selwyn, the necrophiliac MP and Satanist, which had transfixed him just thirty-two minutes earlier. As he moved towards the platform – there was no avoiding the giant, as Doodles had to get to Kings Cross – his recognition of those eyes and shrunken cheekbones was, metre by metre, confirmed. He felt like a mouse in the Jagger villa.

Next day Doodles left the Lido behind, in the care of the local authority, and continued along a rising tarmac pathway. The balconies of an adjacent block of flats displayed plants in pots, ironwork chairs and some sodden towels. Soon he was beyond the flats, the path forked, and he went left, as he had been doing since his late teens.

The path here was narrower. To his right a grassy slope rose gently to a ridge, where a dozen trees crowded together for company. The grass had recently been cut and dead swathes of it lay like tufts of hair on a barber’s floor. Death had made the stems curl and become yellowish. On the slope nine ravens stood at a distance of twenty metres from each other. It was as if they had been placed there by a film director who’d graduated with a special interest in surrealism.

The nearest raven cautiously edged a couple of paces away from Doodles as he passed but otherwise maintained its air of dignified alertness. None of the ravens seemed to be looking for worms, or doing anything but stand amid the dying grass, motionless, lost in meditation. The blackness of their plumage seemed lurid and their normal size was magnified fifty per cent. Perhaps it was the effect of the rain, which had been falling with a mild persistence ever since he’d reached the Lido. Doodles’ glasses were speckled and distorted by watery blobs.

He stopped and glanced back at London. The gherkin was a dull grey and looked less like a gherkin than a styptic pencil. The financial district was a heap of grey cardboard boxes. Only the Telecom tower had clarity. Its encrustation of pale dishes resembled fungi on a dead trunk. The metaphor made him think of the path beyond the golf club at Seaton.

At the foot of the slope a toy train rattled along the line from Gospel Oak, passing a plum-coloured running track. The rain was much denser to the south and the city was fuzzy and smudged by mistiness.

He turned and went on. Beyond the final raven a grassy track skirted the mown area and went up to the brow of the hill. On the skyline a few trees huddled together for company. Doodles moved on to this pathway, the ground beneath his boots suddenly malleable and springy, yielding to his weight with a low squelch of pleasure. He trudged up to the top, the rain determined to glue his jeans to his kneecaps.

An enigmatic rectangle of concrete came into view. As he reached it – was it a covering or the base of something which had long ago been removed? – Doodles was enveloped by mist. A squall of rain struck him hard across the cheeks, which made him think of Alice. How her hot temper and fondness for drugs had excited him in the old days! But now he was alone, half a stone heavier, blundering blindly down a hillside, lashed by icy splashes, embraced by a thickening fog, seeing nothing but a patch of thorns. He was starting to feel like a character in The Pilgrim’s Progress – Mr Wandering Wet-Man. At one point he slipped and almost fell into a narrow ditch concealed by an emerald blanket of wild cress, saved not by Christian fortitude (he had exhausted his quota by his ninth year) but by the thick tread of his boots, size eleven feet, gigantic thighs, and a yoga-friendly sense of balance.

Slithering and skipping, Doodles reached the base of a broad grassy valley. The Diazepam and his momentum bore him giddily as far as the bare, branchless trunk of a strangely uncontoured tree, the smooth surface of which was a uniform chocolate brown. Seizing hold of it to halt his onward movement – the edge of a cliff or a ravine might be just a few metres away in the mist – Doodles was shocked to find himself clinging to cold, greasy metal. As if that human contact triggered synthetic climatic effects, the mist evaporated and Doodles discovered that he was standing underneath some sort of large eight-legged structure. He wondered if it was a drowsy, monstrous spider and he had lately been exposed to a massive dose of radioactivity. That would explain the shrinkage.

It was only when he ran, screaming, towards the nearby lake and momentarily glanced back that he saw what it was. A massive desk with an equally massive high-backed five-spined chair tucked underneath it. Whoever it belonged to – King Kong? – had evidently gone off for a coffee.

Where was everyone? Hampstead Heath was completely empty. Doodles reached the broad tarmac path which passed alongside the lake. Sweating, he ran along it to the next lake and beyond. A muddy gleaming track led up another hill towards woodland. Best to get under cover, he thought, and crossed a tiny bridge coated with chicken wire. Half way up he paused to let a big black shining slug cross. The twin blobs of its antennae swayed from side to side, as if sensing his presence. When it had reached the grass on the far side of the hardened, well-trodden earth Doodles dodged past it and ran on into the wood. Here, vertical strips of lighting were fixed to the trees, joined by loops of finger-thick wiring. Three or four minutes later he saw another, smaller lake. Beyond it was a stage, protected by a helmet-shaped canopy. To his right, stacked deckchairs dripped in a roped-off clearing. Behind them a grey portable toilet leaned at a perilous angle.

Kenwood House came into view, put there by that same surrealist film director. Gravel displaced the tarmac. The magnolia tree was a lush green and nothing at all like the day it had been when he had made Alice laugh by rolling sideways down the slope. He had collided with the metal fence at the bottom, hurting his head and his ribs. A park ranger wearing the insignia of English Heritage ticked him off. Doodles apologised, explaining that he was a Celt and that Alice had run out of money for drugs. The ranger snarled and strode off home to his collection of artefacts from the Weimar Republic. That day the magnolia tree bore an extravagant white, wedding day blossom. Doodles took Alice’s hand and led her through the hornbeam tunnel, afterwards presenting her with a photocopy of pages 702 and 703 from a hardback novel where the hero also walks into this same leafy arbour. Doodles passed through and on towards Dr Johnson’s summer house, inside which he encouraged Alice to drink from his flask of whisky to ease the shivering. It wasn’t there, and only now did he recall that it had been destroyed by fire.

He went on across the lawn to Hepworth’s ‘Empyrean’, which holds the meaning of life. Alice nodded with a deep understanding. Today it was desolate and deserted and people had scratched their initials on the surface. Doodles, who was six and a half feet tall, felt as if his stomach consisted of a large oval-shaped hole. He went inside the house and looked at the dull Vermeer, which established how much guitars had changed. The incomplete circle behind Rembrandt’s shoulder disturbed him, as it always did. Much of the painting seemed fuzzy and dark and out of focus. Doodles remembered it was time for his eye test.

The gallery was empty. Even the attendants had deserted their corner chairs. On the velvet cushion of one a PD James crime thriller lay asleep on its big smug stomach.

The library was sickly with gilt. The enormous bookshelves with their big interminable matching volumes suggested Hollywood’s idea of what a private library should be like. A leaflet gave interesting facts. It took three men eight days to fit the mirrors in this temple of kitsch and neo-classical mediocrity. The only object of interest was a stone bust of Homer, formerly the property of Alexander Pope. It looked significantly different to the bust of Homer once belonging to Alexander Pope in the painting which hung over the fireplace.

On the way back everything was the same, except reversed. Doodles paused to let the slug go by. The lakes were windswept and desolate. The rain fell in the alternative slant. The giant’s desk and chair were still, like the surrounding landscape, unoccupied.

The ravens had gone. On the way down to the Lido, Doodles met a hooded woman coming the other way who gave him a warm smile. He exchanged it for one many degrees lower.

Returning along Chetwynd Park Road, drenched Doodles felt his mood sag. He was very wet and very cold, and the day seemed as blustery and rainswept as that Sunday when the circus departed. All morning there was a crash and clatter of dismantled scaffolding and folded machinery. The lions groaned in their cages and tyres span amid liquid mud. The next day the blueprint was marked out in the field in circles and rectangles of brown dead grass edged by perforations where pegs had stabbed the earth.

A pretty ending. But no Sunday when a circus departed existed in his memory. Doodles did not wear glasses. He was only five feet four, and losing an inch every year. The train was obviously not a toy and the metaphor was arthritic and lazy. The ravens were there earlier but they were not ravens but rooks. Trees have no emotions and do not crowd together for company. Seeds are spilled but only a few take root. The anthropomorphic tendencies in this story are deplorable. The ground emitting a low squelch of pleasure! Rain with malign intentions against the jeans worn by Doodles! And ‘plum coloured’ is a meaningless description, since plums are variously coloured – empurpled, green, rouge, blotchy-brown and so on. Ditto ‘chocolate coloured’. My favourites in a box are always the white ones. And Doodles did not almost fall into a ditch, for there wasn’t one. No wild cress attracted his notice. And there was a mistake made in remembering the library. In fact it took eight men three days to fit those preposterous mirrors.

Between paragraphs twelve and thirteen Doodles went into the coffee bar at Kenwood and ate a hummus and grated carrot wrap, washed down with cappuccino. Giancarlo Neri’s installation was not a surprise and was the express reason Doodles went to Hampstead Heath on Wednesday 24 August 2005. There was no mist around the desk and chair and Doodles did not scream. The slug, which was slug-sized, was not there on the way back. It was in fact the day after the Hampstead trip that Doodles went to Tate Britain to see the Joshua Reynolds exhibition, and not thirty-two minutes but several hours later at Oxford Circus that he encountered the hoarding for the new Rolling Stones album. In between he went to the Twining’s shop opposite the Royal Courts of Justice and bought six packets of Irish Breakfast, his favourite tea. After that he went to Waterloo station to meet someone who was arriving on the Portsmouth Harbour train. The slope he rolled down was in Scotland. There was no ranger. There was a girl and there were drugs but her name was not Alice and she and Doodles never went to Hampstead. The Diazepam was years ago and back then named Valium. Alice never existed, except in a Victorian classic. But the route mapped out in this story is entirely accurate.

The Stormchasers

Adam Marek

It’s so windy today. My son Jakey and I are at the window watching leylandii bow to each other, and the snails being blown across the patio like sailboats.

We’ve been watching for fifteen minutes or so when Jakey says, ‘I’m scared.’

‘Of what?’ I ask.

‘Of tornadoes.’

‘Listen,’ I say, ‘no tornadoes are coming here. Even if we got in the car right now and drove around all day like the stormchasers on TV, we’d be lucky to find one. Very lucky.’

‘But what if we did?’

There is a noise from behind us. We both look at the fireplace. The wind is playing the chimney like a flute.

‘Even if we were really lucky and did find one,’ I say, ‘in England it would be a tiny thing. We don’t get the big ones here.’

‘An F4?’ he asks. We have watched documentaries about tornadoes together since he was a baby. Among six-year-olds, he is an expert.

‘No way,’ I say. ‘An F2, if we were really lucky.’

‘Big enough to suck up a person?’

He is imagining the tornado like a straw in the sky’s mouth, I can see this.

‘Nuh-uh,’ I say. ‘Just big enough to fling a couple of roof tiles about, or knock over some flowerpots, or break a greenhouse to pieces.’

‘But what if . . .’ he starts.

He is not going to believe me, sitting here in the house with the wind whoo-whooing around our walls like a ghost.

‘Go get changed out of your jim-jams,’ I say. ‘I’ll show you that there’s nothing to be afraid of.’

While Jakey looks for his shoes, I pack lunch for us in a cotton shoulder bag: for me, chicken-liver pate and apple chutney sandwiches, and a flask of Earl Grey tea; for Jakey, cheese spread sandwiches, a fun-size Twix and two cartons of apple juice.

‘All set?’ I say when he gets to the bottom of the stairs. He is wearing the bright yellow sou’wester and macintosh that he has finally grown into. I bought them for him before he was born, when he was just in my imagination.

‘Uh-huh,’ he says.

‘We’d better go say goodbye to mum,’ I say.

We creep upstairs together, peep around the bedroom door. Mum is still in bed. She has the light out. Yesterday the dentist at the hospital pulled four wisdom teeth from her mouth. She has been in bed for a whole day, and mostly silent.

‘Where are you going?’ she says. Even her voice sounds wounded.

‘We’re going tornado chasing,’ Jakey says.

‘We won’t be long,’ I say. ‘Can I get you anything?’

‘No.’

‘Are you feeling okay?’ Jakey asks.

She pulls the duvet over her head. ‘Just go away,’ she says.

We drive.

‘It feels good to be out, doesn’t it?’ I say. ‘Seen any tornadoes yet?’

Jakey looks around. He says nothing.

The bendy roads between the hedgerows are full of fallen branches so I go slow. We live in the countryside, a little house all on its own. In the summer, from the air, our plot is a dark green triangle in the middle of a bright yellow sea of rapeseed. I have seen it from the air, in a microlight. The photograph I took is in our bathroom. I stare at it every time I pee.

‘Where shall we go?’ I say. ‘If we were proper stormchasers, Jakey, we’d have a Doppler radar and a laptop so we could find the tornadic part of the storm.’

‘We are real stormchasers,’ he says.

I’m watching the road carefully but I can see his pout from the corner of my eye.

‘You’re right,’ I say. ‘But we don’t have Doppler, so we’ll have to rely on our instincts. You take a look at the sky and tell me where you think the tornadoes will touch down.’

Jakey presses the window button till the window is open the whole way. He sticks his head out. I slow the car and move into the middle of the road so he doesn’t get hit by the sticky-out branches that the hedge-mower has missed. I’m going slow enough that I can watch Jakey. He is looking up into the sky, holding the door frame with both hands. The wind is throwing his shaggy hair all around his head. His hair is cornfield-blond, the same as mine. His mum’s is almost black. ‘Yet another thing he got from you, not me,’ she sometimes says.

‘That way,’ he says, pointing north-east.

When we get to the motorway, the car is hard to control. The wind bullies our left-hand side. The windscreen wipers are overwhelmed with this much rain. We feel enclosed, in the car. We are like a head in a hood. Jakey gets to choose the radio station. He chooses pop music. He sings along.

‘How do you know the words to all these songs?’ I ask.

‘Mum listens to this radio station,’ he says.

I do not like pop music, but I do like to hear Jakey sing.

We’ve been driving for twenty minutes, when ahead we see a smudge of yellow on the horizon. The rain is thinning. The cars coming towards us on the other side of the motorway have their lights off. In the rear-view mirror is a procession of lit headlamps, bright against the bruise-black sky.

‘We should turn around,’ I say.

‘No. It’s this way,’ Jakey says.

‘Are you sure?’

‘Uh-huh.’

We reach sunlight. The wet tarmac around us is steaming.

‘Are you sure the tornadoes are this way, Jakey?’

‘No.’

‘Shall we turn around?’

It looks like the end of the world back the way we came. Within the wall of cloud, there’s a heck of a light show.

‘Okay,’ Jakey says.

I come off the motorway and go round the roundabout three times – our game when Mum’s not in the car. Jakey giggles, pinned to the door by physics.

We go back the way we came. I break the speed limit now because the storm is running away from us. We eat our lunches from our laps while we drive.

‘If you’re scared of tornadoes,’ I say, ‘why do you want to see one so badly?’

Jakey shrugs, finishing his apple juice. It gurgles at the bottom of the carton.

‘Well, I told you we’d be very lucky to see one. Stormchasers drive thousands of miles to find them, drive around for weeks sometimes.’

‘How far have we driven?’

‘About 80 miles. Shall we go home now? Mum’ll be wondering where we are.’

‘Yes,’ he says.

The sun follows us back. We lead it all the way to our front gates. Jakey picks up handfuls of the leaves that are heaped against our porch and drops them again. I put Jakey’s lunch rubbish in the cotton bag before I get out. I open the front door and we both go inside.

‘We’re home!’ I call, wiping my feet.

No answer.

I tiptoe upstairs. Our bed is empty.

‘Dad!’ Jakey calls out.

I run downstairs.

In the living room, the coffee table is on its side against the wall. One of its legs is broken off. The TV is face down on the carpet. The mantelpiece above the fireplace is bare. All the photos and pinecones and holiday souvenirs are on the floor. Some are smashed on the slate tiles in front of the wood burner. On the walls, the pictures are all at angles. Jakey’s toys are tipped from his box.

In the middle of it all, sitting on the floor with her arms round her legs, and her forehead on her knees, is mummy. Her knuckles are bloody.

Jakey moves towards her. I hold him back with my hand.

‘Don’t. There’s glass,’ I say. ‘You okay, mummy? Did you see it, the tornado? When it came through?’

No answer. No movement.

Only she and I know that the story about the dentist was a terrible lie.

Mrs Vadnie Marlene Sevlon

Jackie Kay