13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

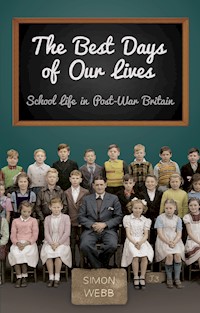

Following the disruption, hardship and challenges of the Second World War, the post-war years brought a sense of optimism and excitement, with families at last enjoying peacetime. This new book follows the lives of the nation's schoolchildren through the two decades following the war years, recalling what it was like for those experiencing the creation of a new school system; a system underpinned by the introduction of the 11 plus exam and the provision of free secondary education for all. Combining personal reminiscences with a lively description of what was going on in the wider world of British education, Simon Webb provides a vivid and entertaining picture of school life during in the 1940s and '50s which is sure to bring back nostalgic memories for all who remember the best days of their lives.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

Acknowledgements

Many thanks go to those who contributed their memories of school life during the 1940s and 1950s: Keith J. Ballard, Peter A. Barker, Ellen T. Cade, Dorothy Dobson, Lilian O. Drake, Sheila Fawcett, Ronald G. Feeney, John B. Fleming, Lorna Gavin, James R. Harker, Brenda Jacobs, Catherine E. Kingsley, Margaret L. Jones, Caroline T. Maxted, Patrick J. McGuire, Glynn Mitchell, Mary Olive, Gregory Parker, Joyce L. Pettitt, Paul M. Richardson, Philip F.A. Robertson, James H. Schneider, Harry R. Smith, Conrad Summerfield, David P. Taylor, Janet L. Thompson, Victor C. Webb and Josephine A. Wilson. Without their help, it would not have been possible to write this book.

Contents

Title

Acknowledgements

Introduction

All Change – The 1944 ‘Butler Act’

Starting School

Primary School

Introducing the 11-plus

Secondary Moderns

Grammar Schools

The Independent Sector

The First Comprehensives

Discipline

Uniforms

New Buildings and Old

Catholic Schools

Religion in Schools

In the Playground and on the Playing Field

Boys and Girls

Qualifications

Into the Sixth

Comics, Magazines and Books

Bibliography

Plates

Copyright

Introduction

This is an account of children’s experiences of school life in Britain during the fifteen years following the Second World War. During that time, education in this country was dominated by the 11-plus examination which divided children at state schools into those who went to grammar schools at the age of eleven and the great majority who did not. The experience of the 11-plus marked every child during this period, except for those at independent schools.

At least three quarters of children at school during the post-war years ‘failed’ the 11-plus and ended up attending secondary modern schools. However, the very word ‘failed’ is an inappropriate one to use in this context. When the 11-plus was first devised nobody was thinking of it in terms of an examination which could be passed or failed. Its aim was to simply allocate children to the type of secondary school best suited to their needs and abilities. Despite the huge impact which it had at the time, it should be borne in mind that the 11-plus was only around for twenty years or so; starting at the end of the Second World War and coming to an end in most of the country in the mid-1960s.

The history of this 75 per cent or more of children who were neither privately educated nor attended grammar schools has often been neglected and sometimes entirely overlooked. Fictional accounts of childhood during this time, from the Famous Five stories of Enid Blyton and C.S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia to the St Trinian’s films, show a world where independent, fee-paying schools are the norm. Real life reminiscences of school in the 1940s and ’50s seem to focus upon the lives of children at grammar and private schools, rather than exploring life at ordinary primary schools and secondary moderns. Through the first-hand testimonies of those who were at school from 1945 to 1960, this book looks at how life was at secondary moderns, as well as grammar schools.

Before the Second World War the overwhelming majority of children left school at fourteen with no qualifications at all. Surprisingly, this situation continued up to 1960, at which time around 80 per cent of secondary school pupils were still leaving school without sitting any examinations and consequently leaving with no qualifications. This meant that most children leaving school could not even think of being able to attend university.

The 11-plus was so important to school children in the post-war years that this book looks in some detail at the real reasons why so many of them ended up in secondary modern schools, leaving school at fifteen with nothing much to show for their years of education. Many older people still feel bitter about their apparent ‘failure’, but, as we shall see, there was good deal more to success or failure in the 11-plus than met the eye.

At the end of this book is a list of further reading for those interested in finding out more about school life in the post-war years.

Simon Webb, 2013

All Change – The 1944 ‘Butler Act’

Any account of British schools in the years following the Second World War must begin with the 1944 Education Act, commonly called the Butler Act, which began the selective education system which existed in this country until the mid-1960s. The Butler Act (named after a Conservative politician of the time, Robert Austen Butler – known affectionately as ‘Rab’) sought to sweep away the elementary schools attended by 90 per cent of schoolchildren and replace them with a system which guaranteed free secondary education to everybody up to the age of fifteen.

As the Second World War drew to a close, it was becoming clear to most people in Britain that life in their country would be very different after the war from the way it was before. A young, working-class man summed it up like this:

There’s a story about Lord Curzon during the First World War. Apparently, he was watching a bunch of Tommies stripped to the waist and washing in a stream. He’s supposed to have said, ‘I never knew that the lower classes had such white skins’. You can just about believe that an aristocrat in the 1914-1918 war was like that; it’s impossible to imagine it in 1940. I remember being a fire watcher during the Blitz, on the roof of a building in the city, passing information to the ARP. We worked in pairs and I was teamed up sometimes with this Right Honourable. If it wasn’t for the war we would never have even met, but as we got talking during the night watch and both found that we weren’t so very different from each other. Both dead keen on girls, drinking and the horses. It was obvious that though we spoke differently, we had a lot in common. It seemed to me as the war ended that Britain wasn’t going to be divided up into officers and ’other ranks’ so much in the future. After all, people were calling it a ’war for democracy’. (Victor C. Webb)

The Second World War was a great leveller in a way that the First World War had not been. For one thing, there was the shared terror of the German air raids, which threatened everybody alike, regardless of class or social background. Professional men, like solicitors and accountants, huddled in air-raid shelters at night alongside lorry drivers and Dockers. At the same time, the hundreds of thousands of city children evacuated to the countryside helped bring a greater understanding between the rural and urban communities of Britain. The war in general and the Blitz in particular drew everybody together and showed them what they had in common, as opposed to how they differed from each other.

British society, before the outbreak of war in 1939, had been divided by class and that division began with and was to a large extent defined by education and schooling.

Before I started school, I was looked after by a nanny, who was an extremely snobby woman. I was taken to the park, but Nanny kept a sharp eye on me and called me over at once if it looked as though the wrong sort of children were arriving at the sandpit. When I started school, this separation from others became even more pronounced. I was at a prep school in West London, and there simply wasn’t any opportunity to meet boys outside my school and home circle. (James R. Harker)

In the 1940s, by the age of twelve, most children’s paths in life were practically pre-ordained. If you knew what sort of school a child attended at that age, you would have a pretty good idea what sort of life they were going to have and what sort of job they would be doing as an adult. By the age of fifteen, these probabilities had become certainties; the child’s future was essentially set in stone. To see why this should have been, it will be necessary to examine the sort of educational system which was operating in this country during the final years of the Second World War.

Today, we are so used to children from all kinds of backgrounds sitting examinations and leaving school with various qualifications that it comes as something of a shock to learn that until 1945, 90 per cent of children in Britain left school at the age of fourteen with no qualifications of any kind. To gain the School Certificate, the equivalent of present-day GCSEs, it was necessary to stay at school until the age of sixteen. Since the great majority of children attended elementary schools, which catered only for teenagers up to the age of fourteen, gaining the School Certificate simply wasn’t possible for most pupils.

I don’t even remember having the chance to sit the scholarship for a high school. I suppose I must have been told about it, but I was at an elementary school in the last years of the war, and we all left at the age of fourteen, which was the practice back then. It would have seemed strange to do anything other than leave at fourteen. I didn’t even know what the School Certificate was until I was asked if I had it in later years when I was applying for a job. You had to stay on to the age of sixteen to get the School Certificate, and I certainly didn’t know anybody who spent that long at school. Straight away, there were a lot of jobs that you couldn’t really get without having the School Certificate. If you wanted to work in an office, they wanted the School Certificate because it showed that you could read and write well, amongst other things. (Margaret L. Jones)

Entering further education without the School Certificate was all but impossible, and it was also very hard to get anything other than manual work without it. Even an ordinary clerical job could prove hard to come by without this vital piece of paper – the proof that one had been educated beyond the absolute bare minimum level. The only way to continue education to the age of sixteen was through either an independent school or a grammar school. The grammar schools were also fee paying, although a quarter of their places were set aside for scholarship pupils. In theory, this meant that any child could sit the entrance exam at eleven and gain a free place; in practice, many of these places were monopolised by middle-class families who couldn’t quite afford the fees. Very few went to working-class children whose parents were manual workers. Even when a bright working-class child was offered the opportunity for a place at a grammar school, there could be other problems:

My teacher wanted me to sit the exam and try for a scholarship at the grammar school when I was eleven, but my parents wouldn’t hear of it. It was bad enough for them that it would be another three years until I could start earning, never mind waiting until I was sixteen or eighteen. Besides, what was the point in a girl staying on at school like that? The teacher even came round to the house to talk to them, but it was no good. So I stayed on at the elementary school and left when I was fourteen and went to work in the same factory as all my friends. (Janet L. Thompson)

I don’t think people today can have any idea of how important it was for children to start earning as soon as possible. That extra wage made all the difference. My mother was counting the days until I left school, knowing how much easier is would make things for the whole family. Once I started, I did what my older brother did, just handed over my wage packet to her. She then gave us back some pocket money, enough to go out on Saturday night. By the time I actually got my first wages, she had already pledged herself in credit at the shops on the strength of my first money. I can tell you, it would have been a right problem for her if I’d turned round and told her that I wanted to stop on at school for another few years. (Gregory Parker)

For other families, the loss of a wage was not the only financial consideration which prevented the child from taking up an offered place at a grammar school. One of the great distinguishing marks of the grammar school or private school pupil was that they wore uniforms. Children at elementary schools wore whatever their parents felt like dressing them in. Starting grammar school, though, meant a trip to an expensive shop for coats, blazers, shirts, ties, trousers, gymslips, caps, hats, games kit, shoes and so on. For many working families, it was simply not possible to find the money for such things. It was enough of a struggle to put food on the table each day without having to kit a child out in this way – this was a time when most children had just one pair of shoes and one coat. Grants were sometimes available, but getting one could be a chancy business.

I passed the scholarship for the grammar school, but when my mother and father found out how much it would cost for me to go there, the whole thing fell through. They had already been fretting about how they would find the money for the bus fare each day; the grammar school was six or seven miles away. When they received the uniform list and totted it all up, that was it. I was an only child and that meant, for some reason, that they weren’t entitled to a grant for the uniform. I don’t recall being much bothered about it to be honest. It meant that I would be staying at the elementary school with all my mates. (Gregory Parker)

I passed the scholarship exam and got a place at grammar school. At first it all nearly went wrong from the first, because my parents were told that they weren’t entitled to a grant for the uniform. This would have sounded the death knell for any chance of me going to the grammar – they couldn’t possibly have afforded to kit me out from their own money. It turned out that they had made a mistake in their application. It was like The Family at One End Street. My father had somehow ticked a box saying that I was an only child, rather than one of five. Once that had been sorted out, we got the grant. There were still a lot of other expenses that weren’t covered by the uniform grant; things to do with sports and days out. Sometimes I had to miss out on school trips because we couldn’t afford to contribute. In some ways, I felt like a charity child, at least compared with those whose parents were paying fees, which was most of them. (Mary Olive)

The elementary schools, which almost all children attended, had their roots in the Victorian era and had originally been set up to educate children whose only prospect was to end up working on farms or in factories. They were known in the nineteenth century as ‘industrial schools’ and aimed to provide no more than basic instruction in literacy and numeracy. By the time children left elementary school, they were expected to be able to read a paragraph from a newspaper, work out the change from a shopping trip and take down simple dictation; that was it, little or nothing in the way of history, geography, science or literature. In many ways, these schools had hardly changed from the late nineteenth century up to the outbreak of war in 1939.

The sort of things we learned when we were twelve or thirteen weren’t much different from what we’d been doing when we were nine. Nothing special happened at eleven, not in the way that kids now move up to secondary school. It was more or less the same all the way through till we left at fourteen. I suppose the best way of looking at it is that our school life in the elementary was just like being at a big junior school from five to fourteen. (Gregory Parker)

The three Rs and, of course, a lot of PE and practical stuff, that was about it. Housework for the girls, only they called it ‘Mothercraft’, and woodwork for the boys. It was like everybody, all the teachers I mean, had already decided that there wasn’t much point in doing a lot with us. They knew we were only going to work with our hands and we wouldn’t need a lot of book-learning for that. In most cases they were probably right, but it would have been nice to have had the chance to try other stuff. We couldn’t all have been so thick that we would only be fit to operate a tractor on the farm or bit of machinery in a factory! (Sheila Fawcett)

Such schools had long outlived their day, and even before the Second World War it was obvious that the state school system needed to be overhauled. The desire to change things and extend secondary education to all children did not come from those whose children were attending the elementary schools. Nor did it come from the pupils themselves; most working-class children couldn’t wait to leave school and start working, and their parents usually felt the same way.

The introduction of compulsory schooling in the late nineteenth century had been very unpopular with many working-class families, depriving them as it did of another wage earner. In the 1880s, prosecutions of parents for not sending their children to school were more common than any other offence in Britain, apart from drunkenness. This reluctance to have a child ‘wasting’ time in school when he could be earning a wage lingered on well into the 1940s and ’50s. The frantic desire to leave school at the earliest opportunity was worrying to local authorities, and it was the subject of a government enquiry in the mid-1950s. It was found that working-class pupils not only left the newly established secondary moderns at fifteen, but that exactly the same thing was going on in the grammar schools, with around a quarter of working-class pupils attending them also leaving at fifteen, before they had a chance to sit any examinations.

I passed my 11-plus and went to the grammar school. I didn’t much like it though. A lot of what they were doing there didn’t seem to have much to do with my life, my interests. I suppose, to be fair, I might have felt the same way if I’d gone to the secondary modern, but I couldn’t wait to leave. This was in 1953, just after they had scrapped the School Certificate and brought in GCEs. There was some talk of me stopping on and taking the GCE, but I didn’t want to spend another year there, I wanted to get a job. I think my parents were pleased, although if I’d wanted to stay on, they would have let me. They were glad to have another wage coming in when I left school. (Glynn Mitchell)

To some extent it is possible to sympathise with the families who felt this way. Teenagers are notoriously expensive to clothe and feed, and money was desperately tight in many homes. The moment that a fourteen-year-old began bringing home a wage could make the difference between being at the point of near starvation and just scraping by.

During the war, the situation in Britain was that many, perhaps most, parents and children saw the years spent in the elementary school as an irrelevant interlude before the age of fourteen was reached and the child was able to get a job. The realisation that this was not a satisfactory state of affairs and the desire to alter the system mainly came from educated men and women, those who had been to university themselves, and their ideas were widely resented by the very people whom they were trying to help.

I hated being stuck at school, ‘specially once I was twelve or thirteen. I was in an elementary school, having to spend all day with kids as young as five. Our school worked on the monitor system, where older pupils taught the younger ones. Here I was, couldn’t wait to join my Dad in the shipyard in a few months and until then being made to help teach the alphabet to a load of infants. Most of the other boys in the school felt the same way. It seemed so unfair. We were big enough to do a days work and yet we were being made to stay with children all day. I didn’t know anybody at our school who went on to secondary school. I suppose I’d heard that you could sit for a scholarship to a grammar school, but really, I would have refused point-blank if anybody had suggested anything of the sort. I wanted to be out in the world earning a wage. As for what my Dad would have said about me spending another three or four years at school, well, he wouldn’t have heard of it. We needed another wage coming in and as soon as possible. (Paul M. Richardson)

As we shall see, this attitude persisted among many families until well after the introduction of free secondary education for all children; with the majority leaving at the first opportunity at the age of fifteen, rather than staying on for another year. The tendency to view school as some sort of irritating institution was still around as late as the early 1970s, when the school leaving age was officially raised to sixteen.

I was at a secondary modern in 1951 and was just marking time till I was fifteen and could leave and go to work. Although I’d failed my 11-plus, I wasn’t too bad at schoolwork, and one day the head sent for me. He said that I might be able to transfer to a grammar school if I sat another exam. This was what came to be known as the 13-plus, it was another chance for those who’d failed their 11-plus. He talked about going to the grammar school, maybe entering the sixth form there and perhaps even going to university. I listened politely, saying ’Yes, sir’ and ’No, sir’ in all the right places. I didn’t even tell my parents about it, I was that horrified at the thought of staying at school for longer than I had to. As for switching schools and leaving all my mates, well it just wasn’t going to happen. He wrote to my parents, but they didn’t care. My father had managed alright without much of an education, and so I stayed on at the secondary modern and left at fifteen like everybody else. (Lorna Gavin)

We are so used to regarding the key ages in a young person’s life as being eleven, sixteen and eighteen, that it comes as something of a shock to realise that until the 1940s, boys of fourteen were regarded generally as grown men; capable of putting in a full day’s work at a man’s job.

I was furious when I realised that the new law would mean I had to stay on at school for another year. It was announced in the spring of 1947 and I would have turned fourteen in the October. I felt that I had been cheated out of becoming an adult. My parents were none too pleased about it either. Things were a bit of a struggle and they had been counting on having another wage coming in in the autumn.

There didn’t seem to be any sense in making us stay on at school for longer. We wanted the jobs, the employers wanted to have us, and now we were being told that we would have to wait another year until we could leave. It wasn’t as though that year would make any difference to us. We mostly knew what we would be doing. (Sheila Fawcett)

It was attitudes such as these, among both parents and children, which had prevented any progress being made with the plan to extend secondary education to all children in Britain. Nobody really wanted it; not the parents, the children, the teachers, nor the local authorities. The existing system had worked well enough for decades and to change it would mean a great deal of expense and upheaval. It is worth noting that it was not only children in elementary schools who could not see the point of remaining at school and were keen to get out into the ‘real world’. Here are two grammar school pupils’ points of view:

I was at a grammar school from 1941 until 1946. I didn’t want to stay on for the sixth form. I was a scholarship boy, and I have to say that most of what we were being taught didn’t seem to have any sort of connection with the real world. What really brought it home to me was the business of Latin pronunciation. We followed what was known as the ’New Pronunciation’. About fifty years earlier, some people had worked out that the Romans actually pronounced ‘V’ as ‘W’ and that ‘C’ was always hard, like ‘K’. This meant that we were supposed to call Cicero, ‘Kickero’. Common Latin expressions like vice versa were also pronounced in the new way, we would learn to say ‘wicky worser’, rather than vice versa. Anyway, there were furious debates about this, with half the class preferring the old-style pronunciation and others being very partisan for the new way. Even the teachers had strong views on the matter. This was all going on in 1945, when I was fifteen. Here we were, in the year that Belsen was on the newsreels and the atom bomb dropped on Japan and I was spending my days with people who were more bothered about how to pronounce the name of some statesman who had been dead for two thousand years. There was something utterly unreal about it. (David P. Taylor)

I think I can safely say that since I left school in 1949, I have never once found occasion to say, ‘Hand me the spear, O my brother’ in Latin. As for the vocative case, I have never been able to fathom why anybody thought that it would be a good use of a twelve-year-old’s time to teach her that mensa meant ‘O table’. I mean, I have never been in the habit of addressing my table in English, never mind Latin. (Mary Olive)

So far we have looked mainly at the views of working-class children who, after the war, would almost invariably end up in the new secondary modern schools. The perspective from those whose parents were paying to have them educated was rather different. Take the pupils above for instance, who couldn’t imagine why they were being forced to learn Latin, and what’s more to pronounce the language in a particular way. What possible relevance did Latin pronunciation have in a world just emerging from the most terrible war the world had ever known? Surprisingly enough, it was of paramount importance for the future prospects of those children whose parents were hoping that they would be able to attend Oxford or Cambridge Universities. A boy who attended a private preparatory school in the late 1940s explains:

By the time I was eleven, I was studying Latin and Greek to a pretty high standard. I remember telling my father one day that I couldn’t see the point in it; I wasn’t ever going to meet any Romans or ancient Greeks, so why spend all that time learning their languages? I asked why I couldn’t learn German or French instead. His answer was short and to the point. ‘You want to get to Oxford, don’t you?’ I mumbled something like, ‘I suppose so,’ and that was that. I still didn’t twig, but one didn’t really argue with my father. If he said I wanted to get to Oxford, then I supposed that I must do! It wasn’t until I was in the sixth that I found out about Responsions and then it all made sense and I was glad that I had spent all that time swotting up on dead languages. (James R. Harker)

There is regular discussion these days in the newspapers about the proportion of state school pupils getting into top universities such as Oxford, but despite this the situation between the end of the Second World War and 1960 was breathtakingly different. At least today, every child at a state school has a theoretical possibility of attending Oxford or Cambridge. Before 1960, the chances of over three quarters of state school pupils of getting a place at Oxbridge were, quite literally, zero. The reason for this was the entrance examinations in operation at both universities.

Entry to both Oxford and Cambridge Universities meant having to pass examinations in Latin, Greek and mathematics. At Oxford this process was called the ‘Responsions’. Obviously, only those at private schools or grammar schools would be studying these dead languages, without which there was no possibility of getting to Oxbridge. For fifteen years after the end of the Second World War, this remained the case; effectively barring the 75 per cent or so of pupils attending secondary modern schools from these universities. Until 1960, only those with a good working knowledge of Latin and Greek could even hope to get into Oxford.

When I went up to Cambridge in 1954, it was still very much a case of the Old Boys’ Network. My father had been there and his father had also been there. They both went to the same college, which was the one I was applying for. I had some A levels, although they weren’t brilliant. The important thing though was that I was pretty good at Latin, Greek and Algebra. I sailed through the entrance exam, my father having paid some penniless student to coach me during the holidays. And that was it; I was in. Whatever strings could be pulled in the background, and I’m sure my father was just the man to do this, it was no good if one didn’t have enough Latin and Greek to get through the entrance exam. That was crucial and I have no doubt that there were boys at ordinary state grammar schools who were much brighter than me but who didn’t stand a chance of getting into Cambridge because they didn’t have Latin. (Conrad Summerfield)

The 1944 Education Act, or the Butler Act, came about as a result of the wartime government’s determination to eradicate poverty, unemployment, ignorance, squalor and disease in the post-war society for which they were already preparing. The tackling of these five ‘giant evils’, as identified in the 1942 Beveridge Report, was to eventually lead to the foundation of the welfare state. Robert Austen Butler, who was appointed to the post of President of the Board of Education by Prime Minister Winston Churchill in 1941, at the height of the Second World War, was given the responsibility of creating this.

The scheme which Butler championed entailed raising the school leaving age first to fifteen and then sixteen and ensuring that every child in the country should have free access to secondary education. As originally envisaged, this would be a tripartite system of grammar, technical and secondary modern schools. The technical schools never really took off and so what remained were grammar and secondary modern schools.