5,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

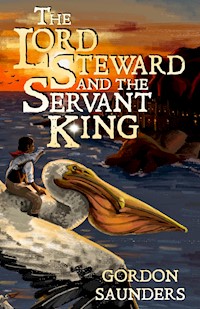

- Herausgeber: mediaropa

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Serie: The Verduran Pentology

- Sprache: Englisch

Dalat was Prince Regent. But he didn’t think about it because it was too far in the future. He thought about the game, beating his opponents. And not simply winning, but crushing them, completely humiliating them.

But then disaster struck. His father’s entire empire collapsed. Enemies took every city. Judgement came. The kingdom was proclaimed ended by some being that seemed to be a sort of Lord, even though it was only a bird. His father was struck dumb and deaf, motionless, empty, but not dead.

Well, someone had to take charge. And he, Dalat, was supposed to be the one. He determined to be king, no matter who stood between him and the crown. No matter that he knew nothing about being king. No matter that no greater crisis had ever faced the kingdom.

So he grasped the crown and put it on himself. But the crown took him to another world, another life, a multitude of other lives, each one more difficult than the last. They were designed to train him, to prepare him to be the king he ought to be. But would he learn? And could it make a difference to his people?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 334

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

The Boatwright

Gordon Saunders

Published by mediaropa press

The Boatwright

Revised Edition

Copyright © 2021 by Gordon Saunders

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-956228-10-6

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-956228-01-4

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-956228-02-1

All rights reserved. Except for use in any review, the reproduction or utilization of this work in whole or in part in any form by any electronic or mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including xerography, photocopying and recording, or in information storage and retrieval systems, is forbidden without written permission of the publisher, mediaropa, LLC. Reach us at: [email protected].

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

Cover art by Anna Coleman

Cover design by Gordon Saunders

gordon-saunders-writer.com

Dedicated to my Apache friend,

Eagle Vittorio,

who finished well,

and to his Lakota wife, Messina,

who keeps faith.

1

THE END OF THE GAME

Glancing briefly toward the balcony above the inside wall of the vastly expanded new coliseum, Dalat assured himself that his father was watching his performance. As usual, he was dominating the game. His white shorts and shirt, dark face and black hair were covered with dust, making most of him beige except the bright red number one on his shirt. Sweat ran through the dust on his face, glinting off flat planes of cheek and chin, dripping down onto his shirt.

At a run, he deftly scooped the ball from the ground with his left hand, placing it in the curved racquet he held in his right. With one fluid motion he swung the racquet backward and downward, then snapped it back up, twisting it slightly, to release the ball. He watched the ball hit the red paddle about the size of a dinner plate, the height of three men above the playing field. The paddle dropped and its attendant reeled it back up to its normal location with the pulley.

“Cha! Cha!” the players cried, rushing to hug and pat Dalat. He grinned and accepted their praise. Of course, they praised him whatever he did, because he was the king's son. But he was good, after all. Denispri would have no difficulty defeating teams coming from council cities all over the Byotik League for the annual Council and games.

Dalat glanced up toward his father again, who nodded ever so slightly, and then allowed his teammates to out-do one another with further congratulations.

Which were cut shorter than he would have liked by Coach calling the two scrimmage teams to himself. As they gathered in front of him, Coach sent a scathing glance toward Dalat.

“It’s a team sport,” he said. “No one can do it alone.”

He didn’t look specifically at Dalat now, but Dalat knew he would direct the next comment at him since they’d run this little scenario many times before. “You may be able to hit the paddle, but could you do it if no one got the ball to you? Could you do it if your teammates were not keeping the opponents from knocking you over as you swung the ball?”

Dalat had asked his father to remove the coach on more than one occasion, but, without actually saying anything, his father had always tilted his head a few degrees to one side and smiled that thin smile that meant No. Dalat’s father, Damal, King of Denispri and Councilor Supreme of the Byotik League, rarely said No to Dalat. But when he did, there was little point disputing it. Coach remained.

He was now arranging the twelve players into two opposing lines almost as far away from one another as the shorter sides of the playing field. Dalat scrambled to get into his position, left-end player on the side opposite the balcony. Coach gave a ball to alternate players on the other side of the field.

When this exercise worked, it was a thing of beauty. Players one, three, and five, slung their balls to players two, four, and six, on the other side, who then slung it across to players one, three, and five on the first side, and back and forth and back and forth. Until, at a precise moment, the coach shouted, “Long!” Player one then slung his ball to player six, player two to player five, player three to player four, and so on and back. If each player did his part, as play continued, no ball would strike another in the air, and at the end, the three players who had started with the balls would have them again.

It had taken them weary months and innumerable practices to get it right, but it made them the best team in the league. And it was going very well this time. Dalat looked up at the balcony once more to see if his father was watching. Fortunately, he was not. Because just as Dalat looked up a ball came his way that he failed to see. He missed it. The rhythm was broken. And shortly the rest of the balls were collected or tumbled onto the dirt. Everyone on the team, as well as Coach, looked at Dalat.

“Something other than the exercise on your mind?” roared Coach.

Dalat shrugged.

Evidently that wasn’t good enough, because Coach continued to stare at him.

“Sorry,” he mumbled, hoping very few people heard.

“What was that?” shouted Coach.

Furious, Dalat now shouted as loudly as Coach had. “I said, I’m sorry!”

Everyone became silent. Finally, Coach said, less loudly, “It’s a team sport.”

Then he turned his head slowly, eventually taking in all the players. “To the baths, everyone,” he said. “Be here at third watch, sharp.”

The players dispersed toward the opening under the balcony.

Dalat shrank from looking toward his father as he left the field. This time, he looked toward a place in the stands where his mother often sat and where she sat now. Despite what had just happened, she was smiling as she glanced his way, and she waved her hand slightly. At least someone could always be counted on.

Sometime later Dalat joined his father, Damal, in the new Council Room that looked out from the coliseum’s balcony. He surveyed those councilors who had arrived. Most of them were swarthier than he, with flatter noses and eyes farther apart. His mother had been a conquest from some place in the south, and being much lighter-skinned than his father, had given Dalat skin lighter than Damal’s. If it was not a problem, that was only because he was the king’s son and no one dared say anything about it.

He gave his attention to the meeting in progress.

“What says the King to the remark of the Councilor of Glini?” asked the dry voice of Kalik, the Councilor of Broll, elegant in his maroon silk and bejeweled necklace.

Damal turned from the coliseum where another practice game was in progress. He nodded to his son and surveyed the dainty group of councilors. Damal had allowed Dalat in the Council meetings from an earlier age than his mother preferred. He had attended, now, for several of his sixteen years. In two more years he would be an official aide to his father.

“You need to get to know these people,” Damal had said, “and how to deal with them.”

Dalat had seen Damal’s technique of staring them down one at a time so that, though the entire group had the power to overrule him, individually, they were under his sway. When he worked his technique well, they seemed to forget they were a group. And each individual did just as Damal wished.

Lored, the Councilor of Glini — the folds of his chin lost in the frills of his collar — was the first to look down. He was followed quickly by Mondu of Mnof who looked away, twitching his moustache. Dineed of Lind glowered momentarily but then faltered. All the others, similarly, except Justin of Lerdi, could not endure his gaze. Damal had told Dalat that Justin would have to be dealt with differently, though just what that meant, he had not yet said. Justin was the difficult one.

“While you gentlemen multiply words,” said Damal, “our adversaries gather strength. As early as next year they could knock at the gates of your cities.” He paused and once more gazed at the thirteen men before him.

Damal was, after all, the military leader whose raids and exploits had helped fill their coffers. Though they squabbled and hesitated, they would follow him. And each one knew it. But they would continue this verbal jockeying for position for a while longer.

Dalat enjoyed watching it. One day he would handle them all as skillfully as his father did. He would play them like a Tospot game. In fact, watching them was much like watching a Tospot game, as the ball passed from one to another and finally back to his father who never failed to score.

Coming back to the council table, Damal stood at its end leaning forward on clenched fists. “It is a good proposal. We need Kalura on the Council. What will it hurt you Lored, or you Dineed, if Kalura becomes a Council City? Is it not said that there is strength in many counsellors?”

“But we have already ships and spice enough. What more can Kalura give us?” asked Dineed. Looking up at Damal briefly he continued, “And is it not also said that too many heads muddy counsel?”

“This will not hurt Lind,” said Mondu. “You compete with Kalura already. It is we who are far away—Mnof, Gdaun, Dall, Beldorn—who will hurt as the League’s attention goes farther and farther from us. As it is...”

“Well,” said Damal, cutting him short, “since Borl has not yet arrived from Beldorn, we will do well to postpone our discussion until tomorrow when we meet in full Council. In the meantime, there are the games this afternoon and the Council feast this evening. The city is yours, gentlemen.”

There was a general muttering as the councilors arose. Dalat saw Kalik catch his father’s eye and raise an eyebrow ever so slightly. He perceived this council would not be quite so pliable as his father and his father’s ally, Kalik, had hoped.

The councilors from Melnor and Bdorna went off with Klarind while Lored and Dineed talked together softly, stealing sideways glances at Damal.

“And where is the full Council to be held on the morrow, Sire?” Justin asked, somewhat icily. Dalat noticed that Justin, like his father, dressed in a simple tunic and lightweight jerkin — not for effect, but for action. He was the only one in the room who spoke his mind plainly. Dalat could see why his father had told him that Justin must be subdued.

“You don’t like our new quarters?” asked the King.

“Is the Council not to meet in the Hall of Truth — with the Mwlahnni — to assure our openness and forthrightness with one another? Has the Council not always met there?”

“Are you, perhaps,” asked the King in a tight voice, “not intending to be open and forthright?”

“I am,” said Justin. Those who remained in the room turned to look at him. He glanced around and said more softly, “Is everyone?”

In a voice just slightly louder than usual, with somewhat exaggerated enunciation, Damal said, “You would accuse your fellow councilors of duplicity?” The King paused to relish the effect this had on those watching.

Justin did not answer, nor did he avert his eyes. Dalat looked back at his father in time to see a scowl racing across his face, quickly replaced by that thin smile.

“Is it not much more convenient not to have to walk once and again the dusty stairs from Council to game, game to Council?”

Justin looked directly at the king and spoke quietly, with complete composure. “Ispri has decreed that we meet there.”

“Oh, Ispri,” said Damal, waving his arm off-handedly. “You haven’t seen him lately, have you?” He looked directly back into Justin’s eyes. This was the test. “Why should we not meet here?”

Justin did not drop his gaze. “It is wrong,” he said.

Then he turned without another word and left the chamber, followed by the councilors from Gdaun and Nanos. Kalik was the only councilor still in the room.

Damal turned to the map of the Byotik League, engraved on the wall opposite the columns overlooking the coliseum. He pursed his lips, gazing absently at it, shaking his head just enough for Dalat to notice.

“This may be more difficult than I had expected,” he said.

Dalat leaped into the air and intercepted the ball slung by a Lind opponent. With deadly accuracy, he threw it to his teammate in the next quadrant. Dalat’s teammates passed the ball to one another, evading Lind players and their attempts to intercept the ball, passing it through the other two quadrants and back toward Dalat, who was now running to his own color, preparing to score. Looking behind him for the ball, he fell headlong over a Lind player who had purposely thrown himself on the ground in front of him.

The crowd rose to its feet as one person, screaming at the offending player. Dalat and his opponent got quickly to their feet and wiped the dirt off their sweat-glistening bodies. Dalat wiped the corner of his mouth with the edge of his shirt, looking stiffly at the other player, and cleaned off the bit of blood that had trickled from his lip. He accepted the ball from the referee and walked to the center of the field.

“Your foul will cost you not one, but two scores, my man,” he said grimly, placing the ball in his sling.

In the incredibly smooth single motion that players all over the League tried to imitate, Dalat swung and released the ball toward his red goal. It sailed cleanly toward the mark, striking it dead center, and then arced over the playing field, more than the length of three good-sized boats, to hit the blue mark behind him.

The crowd roared wildly. Dalat’s teammates took their places to begin the next round of play. Dalat, fists clenched, eyes narrowed, signaled to Coach for a replacement and ran from the field through the door under the balcony.

Moments later, Dalat entered the Council Room, still at a run. He stopped dead and stood for a moment, looking among the guests standing at the periphery of the room. He located his father and watched him glance smugly around the hall, now set for a banquet, until his eyes found Dineed, Councilor of Lind. That was the man Dalat sought. He broke up the conversations of the councilors as he pushed roughly through them, then stopped abruptly in front of Dineed and said loudly, brusquely, “Dineed!”

The room became silent as Dineed turned to face him.

Dalat stood, legs spread, hands on hips, dusty, sweaty, the image of arrogant good health. “Do not,” he said, “allow that scum on a Tospot field again!”

Dineed looked at him silently for a moment, then turned and walked toward the exit. All eyes watched him go in the otherwise motionless silence. Everything waited.

Then, Dalat’s anger spent, he moved gracefully toward his father, seeking the approbation he knew he would receive. His father put a hand on Dalat’s filthy shoulder and congratulated him softly on his play. Conversation resumed. A silver bell announced the first course of the feast. Each councilor found his seat.

Dalat started toward the exit through which servers now entered, to return to the game. But the sound of a tray startled him as it clattered to the floor, crystal smashing, conversation halting. The councilors looked not toward the fallen tray by the exit, but to the columns overlooking the coliseum.

He could not read their faces, so varied were the reactions he saw there as he revolved slowly to look at what they were seeing. But before he saw it, he felt it. He had heard about this all his life, but few had expected to see it. The universe, they thought, did not really contain such things.

2

THE APPOINTMENT OF THE STEWARD

The people who jammed the amphitheater were standing and cheering, jabbering excitedly, eating, drinking, crowded together in a writhing mass. But slowly, in ones and twos and small knots, they responded to what the councilors saw. The cheering and jabbering, the eating and drinking, the motion, stopped. People turned, silently, to face the columns at the back of the amphitheater. Players on the field looked around at the stands, wondering. Gradually, all clamor stopped. The game stopped, the ball rolling to a lonely corner, unwatched. Life, as it had been, ceased.

Finally, all had turned to face the back of the coliseum. Some spectators wandered out into the playing field with the players. They stood looking meekly up at the columns in deep silence. Some knelt. Even in the bright afternoon light of a day just past the rain, they could see the object on the balustrade between the columns glowed. It became slowly brighter, then raised wings, perhaps the span of a child’s arms from tip to tip, fluttered them — spattering great shiny drops all around itself — and folded them away. Then it ceased to glow.

Damal, it said. No one knew how its speech was known. Did it speak into the air? Did its words fall on to the naked soul? In the upper chamber, Damal stood forth hesitantly. Each councilor and serving person sat or stood as if carved from a single chunk of rock.

Approach me, said the voice.

Damal did so slowly. When he was but a few feet before the source of the voice, he went clumsily to his knees, almost as if he struggled within himself whether to do so, but was ultimately compelled.

“My... my Lord,” he stammered, as his lips worked strangely over his teeth and his cheeks twitched. He trembled as he bowed his head, reluctantly lowering his eyes.

I am your rightful Lord; the voice went on. But you have chosen not to be a righteous servant.

Damal’s head fell still further.

I have offered you truth and honest dealing…

Still at the head of the table from where he had not been able to move, Dalat could not help but see and listen. The voice struck inside him like the clear single note of a bell.

Something in him loved it. But something else in him hated it. It angered him that he could be violated in this way. How loathsome to feel rather than to hear a voice. It’s almost like those rock creatures in the Great Hall who speak the thought of others into your mind and take your thought to them. How much better that father has built the coliseum with the Council Room up here so we can conduct our business privately, without every man knowing our thoughts and intents; the way business is carried out in every other part of the world.

But he was wrenched from his thoughts to know the words being spoken.

...but you have chosen, rather, to create your own truth, and to employ the devious methods of what you falsely call diplomacy.

Hear me then, said the voice, Hear me all Denispri, and know that today, throughout the League, the results of your deeds have come upon you. Today is your kingdom lost.

Damal slowly raised questioning eyes toward the speaker. “Can you do this?” his expression asked. Clear, unblinking eyes met his look.

Is there any doubt?

Damal faltered and dropped his head once more. Below, the people watched in stunned silence, perceiving the words within themselves.

Your truth, O Damal, is not true. Your hopes are not my hopes. They will not be fulfilled. It is your fears that will be fulfilled.

Dalat gazed, confused and awed, angry and afraid. He looked at the creature that spoke to his father as no one had dared speak to him before. It stood there, like any bird, perched upon the railing. Its height was not as great as the length of a man’s arm. White was its color, or tawny, with brown speckles on its breast and a golden beak. Its eyes were brown, like the eyes of any falcon. The balustrade supported it.

Yet Dalat had the feeling that of all the objects to be seen, this one, not-so-large bird, was the only thing solid, that were it to release the balustrade, it, and everything else but the bird would go crashing into oblivion. It — but no, he could not call the bird ‘it,’ Dalat realized somehow — He, the bird, would remain untouched, unaffected, undisturbed; would the next instant ruffle his feathers and go back to his grooming as if nothing whatsoever had happened.

It was infuriating. But Dalat was powerless to do anything but watch.

The cities of your League will fall, said the voice. I do not give them to another. They will be gone.

The councilors were no longer still. They looked at one another apprehensively. Dalat watched them. Could this be? But he knew absolutely that it was so. He, the Bird, had said it. That was proof enough.

Damal, the voice continued, there is nothing you can do to prevent this. But if you turn back to truth, you may yet prevent your own destruction.

The Bird trained his gaze now on Dalat. As Dalat watched his father fall to the floor, he felt a scorching sensation in his breast, spreading from his heart outward in all directions. Against his will, he knelt and looked up to meet that gaze. He tried to turn away, but his eyes would not obey. They seemed fastened to those other eyes.

Dalat, the voice said.

It rang throughout his being as if a blacksmith’s hammer had struck an anvil. It was strange, this mixture of hate, fear, anger, yes, but also love and longing, that he felt for this... this invader. His life had been comfortable, pleasant. He had been master of it these sixteen years. But he knew that whatever had happened in the past and whatever else might happen now, something had changed that would not change back again.

Do not follow in the footsteps of your father.

How the passions battled within him! Should he cry out in anger and order this impertinent being to go away? He knew he lacked the power. Should he shake his fist and defy him? It would be like defying the rains. Dalat knew he could not make himself do it. Should he fall on his face, there before everyone, crave his pardon? Ask his acceptance? Beg his guidance? Might he? Could he? He used every ounce of energy he had to look into the face of this… this Bird.

It hung on a thread. No. He couldn’t do it. He could not bring himself to do that. He, therefore, simply knelt, motionless, frozen in indecision; realizing that the being before him knew even these thoughts. The moment passed.

Do not take into your own hands, the creature continued, more gently, that which is meant for another. Your mind cannot contain an understanding of the results that would bring. You may prevent or cause great ruin.

Dalat had remained kneeling, awkwardly, but suddenly found himself released, and rose.

The Bird turned to face the people watching from the coliseum.

My children, said the voice, this place will now cease to be called by my name. It has ceased to be a place of truth. You have ceased to desire to receive from my hand what I would give, but have rather chosen to get for yourselves what you could take. The city will no longer be Denispri, the hand of Ispri. You may call it what you will. Not until the restoration will it bear my name again.

He fluttered once more and a few light drops fell on the balustrade. Then he seemed to grow. Dalat thought the Bird felt larger — larger, in fact, than the whole of Verdura — though Dalat could see no difference in him. He, himself, seemed puny, insignificant. And then the feeling passed.

Seek the truth. Obey your leaders. Do what is right and just. Then we shall see. You may yet find glory before the end.

He turned back to face the councilors. Justin, my son, he said, and your friend, Cloros of Nanos. Come before me.

The two walked slowly, but with assurance, from the back of the room. Justin’s eyes radiated joy, and his countenance almost seemed to glow, as Ispri had glowed earlier. He and Cloros fell to their knees with apparent gladness, despite the fact that Damal lay stricken beside them.

“My Lord,” said Justin, “what is your will?”

You have served me well, my son, said Ispri. Would you continue to serve me now?

“Oh, yes, my Lord,” said Justin, “with all my heart.”

And would you, Cloros, choose also to serve me and your friend Justin?

“I would, my Lord,” said Cloros.

Ispri’s light grew. It will not be easy, he said. The Mwlahnni are taken from the Hall of Truth. It is now only the Great Hall, as they have called it here. You must maintain the truth for yourselves. Can you do so?

“We will try, my Lord,” said Justin. “And will succeed with your help.”

“But our own homes,” said Cloros. “Are we not to return there?”

Ispri’s glow seemed to dim slightly and his voice became more gentle. I am sorry, my child, he said, But you will soon have no other home than this city. Your homes and the people you have left there will be no more.

Both Justin and Cloros, indeed, all the councilors, looked at Ispri in disbelief and grief.

Dalat looked at him in raising anger. Who gave you the right…

It is done, my children, he said, and it settled on their minds softly but with force; infinitely kind and painful. But that is not the end of home, for you or for them.

Then in a voice Dalat felt would break stone from the inside; not loud, but full of power and authority, Ispri said: You, Justin, will be Steward here. You will hold the city for the king in his absence. The position of Steward is given to you and your sons forever, if they continue to be faithful. Instruct them so.

He turned to Cloros. You will be the Steward’s Man. Help the Steward as he seeks truth, what is right, and what is good. Ispri looked back to Justin. In the King’s reign, you will be as his right hand. Cloros will be as your right hand, and his sons to your sons. Keep faith.

It appeared that the Bird was now glowing more brightly. But one’s eyes were not to be trusted. Perhaps it was in one’s soul that the brightness was felt. But whichever it was, the people in the coliseum below had to turn away from the brightness. The councilors covered their eyes and moaned for fear.

Damal lay unmoving on the floor. Justin and Cloros rose and looked at Ispri.

Dalat groaned and turned from them. He could not believe it, but the Bird’s light seemed to fill them with joy greater than the grief they should be feeling.

He covered his eyes partially with his hands but looked cautiously at Ispri from between his fingers. As the moment lengthened, he edged his hands from before his face. In the internal struggle, longing almost won. But the, the Bird… Ispri, was gone. As quickly and silently as he had come, he was gone. Damal remained motionless. Some councilors simpered. Justin and Cloros glowed.

As the glow faded, Dalat glanced quickly at himself and saw that even he had a slight glow; especially on his hands. But it was not so bright as theirs, and it soon faded. The first one to move, he ran to his father.

3

THE END OF THE LEAGUE

People in the amphitheater slowly rose and made their way to the exits. Some, here and there, glowed slightly with the light that lit Justin and Cloros, while others, who seemed to have taken a mortal injury, were helped along. There was no more excited babble, no pushing or jostling, no hurry.

Life resumed slowly in the banquet hall. The maid who had dropped the tray stooped to retrieve it and the larger pieces of broken crystal. The councilors looked at one another dazedly and murmured. They had raised Damal to his feet. He stood with his arm around Dalat, and his eyes focused on something only he could see. He was silent, trembling slightly.

“Come,” said Justin to Dalat. “Let us help your father to his seat.”

Dalat looked at Justin suspiciously. “He is still king here, and I am the king’s son. We need no councilor from Lerdi to help us get about.”

He moved his father clumsily to his seat at the center of the table and helped him to sit. Damal’s hands dropped listlessly to his side, while his head drooped. Dalat raised his father’s head and leaned it carefully against the back of the chair. The mouth fell open, and spittle drooled from one corner onto his beard. The eyes stared away vacantly.

The chief groomsman rushed in and ran to the spot before the table from which the king was to be addressed. Bowing, he spat out the words, “Sire, your councilor Borl from Beldorn has arrived. He is in...”

The servant glanced at the unresponsive king and around at the others in quick, apprehensive motions.

“He is momentarily indisposed,” said Dalat.

“He... he...” said the servant, pointing to the door.

His arms over the shoulders of two elegantly dressed grooms whose finery he was dirtying, a tall, unshaven, disheveled man was brought slowly in, gasping and coughing. The councilors looked at him aghast.

“Borl?” said Kalik.

“Gone!” choked Borl. “All gone!”

The others now rushed to help Borl to a chair, shooing the servants.

“What’s gone?” asked Justin quietly, when Borl was seated.

He coughed, held his throat and looked up imploringly at the councilors staring down at him.

“Beldorn!” he bellowed. “Glini! All the villages! Gone, I tell you! They’re gone!”

He dropped his head and sobbed. Then he gasped for a minute, finally looking up. The councilors crowded around him, urging him to speak.

“They took Beldorn from the sea,” he said, coughing.

“Who?” asked Dalat, still at the side of his uncomprehending father. “Who took Beldorn?”

“I don’t know,” said Borl. “We had just left when messengers came after us telling us to hurry and return. We were under attack.” He held his face in his hands and wept. “But there were so many of them... so many.” He raised his head and threw out his arms. “All over!” he cried. “The land was black with them. Smoke was rising from the city and we could not get back, so we turned toward Glini to find reinforcements.”

He turned a pathetic face toward Dalat. “That eight-day journey we made in three days! But when we got near Glini...” He bowed his head and sobbed. “Rubble. Rubble on the Glin and smoke in the air. And soldiers. Swarms of them on the banks.”

Raising his head, he said, “My companions were slain there, and I barely escaped. After hiding... hiding under the hulk of a burned-out galley, I escaped, crossed Lake Lahnn, and here I am. It is an evil day.” Sobs engulfed him.

The surrounding councilors patted his shoulders, and one brought him wine.

Dalat considered his words. Ispri had said it would be so. His internal struggled continued.

Suddenly a messenger broke in on the run. He glanced about and ran to kneel in front of the table before the king. “Byon, Sire!” he cried. “Byon is taken! They crave your help, Sire!”

The messenger looked up at the king who sat vacant, unseeing.

“The king receives your message,” said Dalat. “You may go to the scullery and refresh yourself.”

“Byon?” asked Kalik of no one in particular. “Why, that is not two days’ journey from here! I must get home to warn Broll!”

The councilors from Melnor and Bdorna, with him, sought the exit. But they were prevented from going out as two more messengers burst into the hall. They ran toward the king.

“Soldiers march on Lind from Byon!” said the first. “Send help, Sire, or we are doomed.”

“Bdorna is fallen,” said the other. “A blonde race with white skin and blue eyes — in ships as numerous as the marsavaal before the rain — came suddenly upon us. Only those at sea survived, and few of those. Woe, Sire! Woe has befallen us!”

“This is treachery!” roared Klarind. “From the east as well as the west? Our enemies are in league against us!” He looked around, glaring at the councilors.

“Did we not warn you of this? Did we not?” Klarind shouted. “And now it has come about!”

Another messenger ran in, falling exhausted before he got to the king. Justin moved quickly to him and lifted him gently.

“What?” he urged. “What would you tell us?”

“Lerdi,” the messenger gasped. “Lerdi is besieged.”

Justin lowered him slowly into a chair and shook his head.

Yet another messenger ran in. “Melnor burns!” he cried. “Melnor burns, and they follow hot after us!”

The councilors scrambled for the doors. Dalat held his father’s head against his arm and slapped his unfeeling face lightly.

“Father!” he whispered urgently. “Father! What shall we do? What shall we do?”

The king made no response.

From his position atop the wall over the main gate of Denispri, Dalat watched an old woman struggle up the last dusty paces to the gate. She carried her water pot—great grey thing half her size that it was—slung across her back and filled with a few pieces of timber that must have been part of her dingy cottage. She seemed to be wearing all the clothing she possessed, all of it black and too large. Probably she lived by the canal that came from Broll, because two waterfowl, keening piteously, followed behind her, waddling and fluttering in spells.

Before and after her the dismal parade of refugees continued to pour into Denispri. For some reason, the enemy had not pushed their attack from Melnor right on to Denispri, so the city had a brief reprieve in which to prepare for the coming assault. The environs of Denispri provided almost no permanent vegetation, and all wood in the vicinity was being brought into the city, both to fuel Denispri’s fires and to prevent the enemy from using it to build siege works. Cottages of wood and barges were dismantled. Even the wooden locks that had made the By navigable between Denispri and Broll were taken apart, and the small harbor was allowed to go dry. Justin had taken charge of these works, and they went well.

The enemy would have to make the five-day journey from Melnor on foot. And if he chose to go to Broll, he could make that six-day journey on foot as well. Dalat watched the steady stream snake its way up the steep By Road. The remaining cottages at its side and on the By stood empty now, their owners encamped in the amphitheater or billeted with friends or relatives in the city.

Dalat doubted that one stone of those cottages would stand on another when all was done. But what could he do? The councilors loyal to his father were wavering. It had been three days and his father was no better. All life, spirit, awareness, had left him. And what did he, Dalat, know about being king?

Should he allow them to make him king, as some had suggested? And would he really be king if the entire council did not approve, or if the proper king were still alive? And, again, what did he know about being king, anyway? He shook his head to clear it.

It was the fifteenth of Melver. Green clouds thickened above. The marsavaals winged their way back and forth through them, gleaning their thin living of airborne spores. Even under threat of attack, men in harvester kites did the same. The rain would come in six days. That meant the enemy must come before that time, hoping to take the city quickly, or wait until after the rain.

“What did you mean, don’t follow in my father’s footsteps,” said Dalat quietly, shaking his fist in the direction Ispri had flown three days ago. Surprised soldiers on the wall turned and surveyed him. Uncaring, he continued.

“He has made slaves of all the rebellious peoples who would not accept his rule. We have never had more timber than the slaves cut near Gdaun and Glini. We have never had more silver and copper and tin and iron than they mine in the Tinhills and Dall and Mnof. And we have the clay waterpots from Bdorna, the ships from Melnor, Glini, Kalura. And we have taken the land of the fools of Glindor who thought they could resist us and believed us when we said we would live in peace. What do you mean, don’t follow in my father’s footsteps?” shouted Dalat. “He has done well!”

“He may have done well,” said a voice close beside him. Dalat turned, startled, to its source. “But he has not done right.”

Justin leaned on the top of the wall, slightly turned toward him, a sword alongside his left leg and a leather helmet now supplementing his tunic and jerkin. He did not look at Dalat unkindly, but Dalat responded to him unkindly.

“Oh,” said Dalat in disgust, “What do you know, Justin, ignorant provincial that you are.” He turned back to watch the refugees. “His is the new way of doing things. You provincials are so backward.”

“Perhaps,” said Justin quietly, grimacing. “Perhaps we are backward. But what your father did is not new. Nor did Ispri command us to restore the old times. Both your ‘new’ way and the old way of doing things are always with us. One is called ‘right’, and the other is called ‘wrong’.”

From where they were standing, Dalat and Justin could see much of the By road winding its way up to the city. A sudden noise near the top caused Justin to look down at the road. Another old woman, who had been carrying her massive waterpot, seemed to have slipped and dropped it. What they heard was the noise of the pot clattering off the side of the road, smashing itself on rocks as it rolled and bounced away. The old woman stumbled to a sitting position on the road and began wailing.

Dalat looked over the parapet along with Justin to watch the scene unfold. In just a moment, a soldier had made his way to the woman and appeared to be helping her up. She pulled her arm from his grasp, but as she did, he pointed just above himself. A young woman approached them and offered the older woman a pot — not so large as the one she had lost, but large enough that she could still collect sufficient rain residue to feed herself.

The old woman stopped wailing, took the pot and set it down, and then hugged the younger woman.

“That,” said Justin, with an apparent lump in his throat, “is doing what is right.”

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)