Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

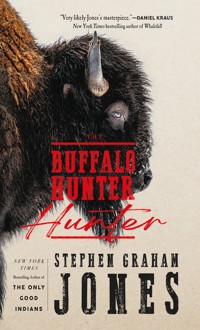

A chilling historical horror set in the American west in 1912 following a Lutheran priest who transcribes the life of a vampire who haunts the fields of the Blackfeet reservation looking for justice. Perfect for fans of Bury Our Bones in the Midnight Soil by V. E. Schwab and Interview With The Vampire by Anne Rice. Etsy Beaucarne is an academic who needs to get published. So when a journal written in 1912 by Arthur Beaucarne, a Lutheran pastor and her grandfather, is discovered within a wall during renovations, she sees her chance. She can uncover the lost secrets of her family, and get tenure. As she researches, she comes to learn of her grandfather, and a Blackfeet called Good Stab, who came to Arthur to share the story of his extraordinary life. The journals detail a slow massacre, a chain of events charting the history of Montana state as it formed. A cycle of violence that leads all the way back to 217 Blackfeet murdered in the snow. A blood-soaked and unflinching saga of the violence of colonial America, a revenge story like no other, and the chilling reinvention of vampire lore from the master of horror.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 711

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Praise for The Buffalo Hunter Hunter

Also available from Stephen Graham Jones and Titan Books

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

The Beaucarne Manuscript: Part 1

16 July 2012

The Absolution of Three-Persons: March 31, 1912

The Nachzehrer’s Dark Gospel: March 31, 1912

The Absolution of Three-Persons: April 3, 1912

April 7, 1912

The Nachzehrer’s Dark Gospel: April 7, 1912

The Absolution of Three-Persons: April 11, 1912

April 13, 1912

April 14, 1912

The Nachzehrer’s Dark Gospel: April 14, 1912

The Absolution of Three-Persons: April 18, 1912

April 22, 1912

The Nachzehrer’s Dark Gospel: April 22, 1912

The Absolution of Three-Persons: April 23, 1912

April 25, 1912

April 26, 1912

April 28, 1912

The Nachzehrer’s Dark Gospel: April 28, 1912

The Absolution of Three-Persons: May 1, 1912

May 12, 1912

The Nachzehrer’s Dark Gospel: May 5, 1912

The Absolution of Three-Persons: May 26, 1912

June 2, 1912

The Beaucarne Manuscript: Part 2

12 January 2013

17 January 2013

20 January 2013

21 January 2013

STILL 21 January 2013

22 January 2013

January 23, 2013

Acknowledgments

“For me and vampires, there is Stoker, there is Rice, and now there is Jones. It’s harrowing, agonizing, nuanced, and downright philosophical. Very likely Jones’s masterpiece.”

— DANIEL KRAUS, New York Times bestselling author of Whalefall

“Stephen Graham Jones has lit a slow-burning candle that grows into a forest fire, illuminating the life of a Pikuni vampire and everyone he has touched, the pain of being a victim and perpetrator of violent history, and how memory serves to keep us who we are despite it all. The Buffalo Hunter Hunter is beautiful, terrifying, sad, funny, and grotesque—everything I want in a novel.”

— JESSICA JOHNS, author of Bad Cree

“A master at blending horror, suspense, and culturally rich stories that are as thought-provoking as they are spine-tingling. Jones’s singular voice and exploration of identity, of trauma and survival, make every page pulse with kinetic urgency.”

— DAVID ROBERTSON, author of The Theory of Crows

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM STEPHEN GRAHAM JONES AND TITAN BOOKS

The Only Good Indians

THE LAKE WITCH TRILOGY

My Heart is a Chainsaw

Don’t Fear the Reaper

The Angel of Indian Lake

The Babysitter Lives

Killer on the Road

The Buffalo Hunter Hunter

Stephen Graham Jones

TITAN BOOKS

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Buffalo Hunter Hunter

Print edition ISBN: 9781835414309

E-book edition ISBN: 9781835414323

Broken Binding edition ISBN: 9781835414705

Abominable Book Club edition ISBN: 9781835414699

Waterstones edition ISBN: 9781835414712

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: March 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Stephen Graham Jones 2025.

Stephen Graham Jones asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

EU RP (for authorities only) eucomply OÜ, Pärnu mnt. 139b-14, 11317 Tallinn, [email protected], +3375690241

Typeset in Adobe Caslon Pro 11.5/16.5pt.

for James and Lois: thanks for all the jelly

but the adversaries are treating the case in such a way as to show that they are seeking neither truth nor concord, but to drain our blood

—THE APOLOGY OF THE AUGSBURG CONFESSION, THE BOOK OF CONCORD

THE BEAUCARNE MANUSCRIPT

PART 1

16 July 2012

A DAYWORKER REACHES into the wall of the parsonage his crew’s revamping and pulls a piece of history up, the edges of its pages crumbling under the fingers of his glove, and I have to think that, if his supervisor isn’t walking by at just that moment, then this construction grunt stuffs that journal from a century ago into his tool belt to pawn, or trade for beer, and the world never knows about it.

If this works out, though, then I owe that dayworker my career.

In January, I wasn’t exactly denied tenure, but I was told that, instead of continuing with my application, I consider asking for the extension I’m currently on. The issue wasn’t my teaching—I’m the dayworker of Communication and Journalism, covering all the 1000- and 2000-level courses—it was that my publications aren’t up to University of Wyoming “standards for promotion.” See: get a book under contract, Etsy, and then we’ll talk.

And, if you don’t? Then all your schooling, all your dreams of being a professor, they’re smoke, and you’re out in the cold.

Until that random dayworker reached into that wall. Until what he found wrapped in mouse-chewed buckskin wound up in the hands of Special Collections librarian Lydia Ackerman of University Montana State up in Bozeman, and she was able to read the scripty hand enough to glean a name from the very front page: “Arthur Beaucarne.”

It’s not far from there to me, that surname not exactly being common.

And, because technically that journal belongs to me—well, my father then me, but my father in his facility down in Denver’s not exactly compos mentis—Lydia Ackerman’s been sending me the digitized pages as they’re processed, the original being a century too delicate to handle. But I don’t think she does it out of kindness. It’s to keep me from showing up unannounced again.

“Etsy?” she asked when I did show up like that in May, breathing hard from the stairs. She was looking from my ID to me, to see which was the typo. It’s Betsy, really, I didn’t say, but a boy with a speech impediment in kindergarten . . . who cares?

“The last name,” I told her, as politely as I could.

So, I was led back to the workbench they conserve delicate literary artifacts on, was made to mask up, glove up, bootie up, and then sit like that through a lecture about the lignin content of old paper and the homemade inks of the late nineteenth century, and how this particular ink had aged into acid that was eating away the brittle old paper it was written on, meaning the individual letters collapse into hopeless crumbles from just the slightest breath—thus the case the journal’s enclosed in. It’s for humidity and temperature, Lydia Ackerman explained like giving a tour to second-graders, but mostly it’s to keep any breeze from punching those black letters from the pages, effectively erasing this amazing find from history.

“It’s also for dust,” Lydia Ackerman leaned forward to say in some sort of confidence, like “dust” was a profanity in this particular room. “Even dust weighs enough to make the letters fall through the paper.” To be sure I got how dire this all was, she heated her eyes up and raised her eyebrows.

“I’ll be careful,” I assured her, at which point she unlatched the glass case, both of us holding our breath behind our masks, I’m pretty sure, and, finally, I got to look directly at my great-great-great-grandfather’s journal.

The workroom we were in smelled like my dad’s chemistry lab on campus, sending me back to being ten years old, when I’d yet to betray him by choosing the humanities over hard science.

Sorry, Dad. Again.

I turned my back on chemistry, became an alchemist, yes, mixing facts with rhetoric and spin and encomium, all in hopes this or that speech will catalyze an audience, hopefully in what feels like a heartfelt way. Such is communication, which I long to enter into again with you someday, Dad—hopefully soon. I do get the reports from your medical team, after all.

But, as my great-great-great-grandfather says in his journal—okay, my greatest-grandfather—that’s neither here nor there.

And, yes, okay, I’ll admit it here in the privacy of this laptop: since I didn’t inherit “science” from my dad, I’m here choosing to inherit journal-keeping from someone much deeper in my bloodline. Well, either “inherit” or “resuscitate”—I haven’t kept my precious thoughts in a secret notebook since junior high, thought I’d outgrown that kind of stuff. Surprise, I guess? I’m still that awkward girl in seventh grade, except now the enemies I’m putting on my hate list are from my tenure committee.

But, Great-Great-Great-Grandfather, I know I’m nowhere near as practiced as you, with organizing my daily thoughts and recollections on the page. You were educated in the nineteenth century, when recitation was the order of the day. You could recite long poems and speeches, and I, who teach speech-writing, can barely remember a phone number.

Where we’re also different: you were a pastor, and—this I did inherit from my dad—I’m more of a professional doubter.

I’ve worked my way through the first few days of your journal, though, and I’m coming to understand why Bozeman wants to pay to keep your writing in their collection. You were good, Arthur Beaucarne. You used my rhetoric and spin and encomium to come off sounding heartfelt, never mind the actual facts, but you had a documentarian’s eye, too, didn’t you? And a playwright’s ear. You didn’t have a camera, but you had a pen, and its nib was sharp enough to cut right to the center of the day, the year, the era.

You make your case better than I can, though. I’ll paste in a news item from 1912, the year you disappeared from your church, and then showcase your more fleshed-out version:

“Is it happening again?” This is the question former cavalryman and current postal clerk Livinius Clarkson was said to be asking his patrons for the better part of Monday.

What L. Clarkson is talking about is the deceased individual found off the beaten path yesterday, out in the open prairie across the Yellowstone River, in the environs of Sunday Creek. Initial speculation was that this was some unfortunate who perished over the last winter, who was only just now thawing out due to last week’s abundance of sunlight. This would explain the state of this person’s remains. However, knowledgeable men involved with transporting the body into town assure the Star that this isn’t frost burn or scavenging. They also assure the Star that while ice, when affixed to skin, can possibly remove it, this would seem to be something more pernicious and intentional.

This is cause for concern.

Are the Indians turning hostile again? If so, which ones? The Crow, the Nakota, the Ree? More farflung tribes like the Blackfeet, Gros Ventre, Snake? And, if this is a holdover from the depredations of older times, then what might be the cause of their ire this time? Does our government not provide them with beef rations, and land that they leave fallow and untended, not interested in working it as God intends?

When pressed on the matter, L. Clarkson, himself no supporter of the Indian, averred that what he was concerned about instead was similarity to a rash of grisly discoveries he claims went on nearly four decades ago, in Montana’s more lawless times.

As for that supposed rash of mutilations, the Star talked to an unnamed source in the later years of his long and storied life. Once a miner, among other and sundry occupations, this source remembers this country when it was “young and open.” Scoffing at L. Clarkson’s sensational claims, this former ore-worker, treasure hunter, stage-coach driver and occasional cowpoke, who was young when the so-called “mountain men” were in their dotage, remembers that as the great buffalo herds were collapsing some 40 years ago, there were motherless calves left bawling out in the night, until finally the men of “Milestown” as he still insists upon calling Miles City, went out and dispatched them in a single night, leaving the humps skinned as a warning to any more disturbers of the night’s peace. Apparently they drew all the calves together by draping a buffalo robe over a large bull borrowed from a certain rancher, also nameless.

The hides they salvaged from these calves, being too small for a robe and too golden for the milliner, were initially stored on a pallet in a shed behind the old livery, until they got too scabby to work soft. At which point they were fed to hogs. This recollector of former times assures the Star that this spectacle is what L. Clarkson is inaccurately recalling, as a buffalo calf weighs about the same as a grown man, and, dead in the grass in the state they were both left, it would be easy to mistake one for the other.

Of note is that the two dogs that accompanied the party to collect this dead individual both expired overnight, each of them chewing at the skin of their own bellies. But of course there is no shortage of dogs here in Miles City.

The identity of the deceased individual is as of this date unknown, save that he was male, and possibly a traveler, as his unmarred face isn’t known around these parts.

The service for him will be private.

That’s the just-the-facts version from the Miles City Star, dated March 26, 1912—microfiche, yes. Now, here’s what my greatest-grandfather wrote into his journal the evening before:

Yesterday evening, word started to percolate around town concerning a man found dead out in the sea of grass that surrounds us. Martha Grandlin, Skeet Grandlin’s second wife (his first, deceased) was the first bearer of this savory tidbit, being certain to contort her face in cultured disgust, and to not give the secondhand account her full voice, I presume either to keep it from being a real occurrence, or to keep from exposing herself as one who thrills in carrying such morbid news around town. Martha, kind soul that she tries to be, was bringing by half a loaf of German bread and some jam she claimed were spare, and clutching the week’s mail to her side in case one of Skeet’s many and farflung correspondences should blow away into those same grasslands.

According to Mrs. Grandlin, who held the tips of the fingers of her right hand to the hollow of her throat while pronouncing this, this poor man had had, there’s no other way to say it, his skin removed “as if he were an animal!”

I ate the bread and jam in silence after Mrs. Grandlin’s hasty departure, and considered whether a man liberated of his skin and left out in the grass was something that could still happen in this new century. Weren’t such things supposed to be part of this new state’s sordid past? And what would motivate someone to such an act? What could someone do to have such an act visited upon them?

The jam was huckleberry, with large chunks still remaining in it, and I found that if I had the patience to leave it on the bread for a few minutes, the juice from the jam would soak in and soften it, with the result being almost in the cobbler family, though I could hold it in my fingers if I was careful, the crust being stiff from yesterday’s oven. I had told myself when Mrs. Grandlin handed this treat to me that I would make it last the week, that it could be the prize at the end of my duties, but once I figured out the proper soaking time, I greedily consumed all of it in a single, shameful go. God was watching, as he watches all, but assuredly he would allow a broken old man this simple indulgence, would he not?

And thank you, Mrs. Grandlin. This midafternoon delight was unexpected. As, of course, was the terrible news. This is Montana, though, I told myself. It’s where things like this happen, isn’t it? Or, as some of my parishioners might joke, “It’s where things like this happen, n’est-ce pas, Pastor Beaucarne?”

In spite of my protestations about any immediate French ancestry, still these Prairie Deutsche like to poke and prod, which is why I write this in King George’s English, not the German I deliver my sermons in, as curious eyes could then read it. But of course my parishioners’ aspersions about their good pastor’s Gallic name is all in good fun, and if the victuals continue to flow, then this non-Frenchman can only be grateful.

As to who the unfortunate man found dead a few miles either north or west of town was or is, or will be upon identification, Mrs. Grandlin had not an inkling. Though the intensity with which she watched me while delivering this served as explanation why I had been her first stop. As the clergy parishioners come to me with their problems and struggles and concerns, it stood to reason that I might have heard news about a husband, brother, or son who had tragically gone missing.

I had no knowledge of any such missing husband, brother, or son, and surely my expression didn’t suggest otherwise, but, infected by Mrs. Grandlin’s curiosity, I told myself to pay special attention. At the same time, not everyone feared to be on a drinking binge is actually drunken. Not everyone supposed to have taken work that pulls them suddenly away from home is actually earning a wage.

Eager about this find out in the grasslands, if for no other reason than that it broke the tedium, I buttoned my greatcoat over the new and persistent huckleberry stain on the surplice I had thrown on when Mrs. Grandlin knocked—my only one!—and made my way out the side door and down to the lodging house porch, bringing with my personage, as it’s unavoidable not to do, a retinue of raucous dogs of every color, size, and temperament.

As I approached with them barking around my feet, announcing my arrival to the whole of Miles City, the whole of Montana, I took pains not to notice the shuffling and scraping that always precedes my arrival to such a low place. I would be similarly unaware of any bulges in the mens’ jackets that could or could not be bottles and spirits, and I held out hope that I wouldn’t have to draw close enough for their breath to scald my eyes.

“The limping reverend!” Willem Thomlinsen called out with all the joviality he could muster, referring to my gait, impeded as it is by the three toes on my left foot that predecease me. I would expect the same from a ten year old boy caught antagonizing the chickens. Thomlinsen calling me by that appellation—Reverend—was a long standing hallmark of our interactions, my silhouette evidently prompting whosoever I encountered in my doddering perambulations to make joke upon joke at my expense. Such is the price exacted by these black robes, I surmise. By this craggy, thin silhouette.

Though I would wish it otherwise, Thomlinsen’s was a joke that had over the previous year spread through his companions like grass fire, meaning I also had to endure as greetings from all these lodging house regulars a round of “Pastor” and “Preacher,” “Brother” and “Bishop,” and on into variations they had to mumble, as they had no real command of the terms, their childhoods spent in Quaker and Catholic pews so far behind them now as to be but fairy tales that happened to someone else.

“Father, Reverend,” Thomlinsen rounded it all up with, apparently having had more training than the rest.

The humor of the west knows no bounds, respects no boundaries.

Nevertheless, I demurred and endured, grinning a sheep’s grin at this camaraderie and acceptance, which is what I have to tell myself it is, every next time it’s happening again.

As to why I’d chosen to submit myself to this good willed badgering, it was that the porch of the lodging house was the catch basin for all news in and around Miles City. The gentlemen, or “denizens” if that’s the more telling description, of the long, swayed bench that I’ve been assured was salvaged from a previous, temporary incarnation of my esteemed church, were irreverent and oftentimes in one stage or another of intoxication, but resistance to observing the niceties of society meant that they functioned as guards at a post, such as it was, not letting anyone interesting pass unless and until they had shared the news of the day with them. In such a way are tolls exacted.

Knowing that any corpse found either north or west of town would come in past the lodging house, I knew then also that such a parade passing in front of the lodging house would have been subject to inspection and interrogation. It helped that Sall Bertram, the quiet Ulysses Grant of these regulars, had, until 1899, been sheriff of Custer County, and that the current sheriff had been his deputy, so was still beholden to his former superior officer. Which probably in no small way explains why the porch of the lodging house was outside the law, as it were.

But that’s neither here nor there, as I hear more and more of my parishioners saying of late—a verbal trend that worries me, as it sweeps things under the rug that should be dealt with in the light, rather than let fester. But this concern itself is neither here nor there, I suppose. Even a preacher pastor brother bishop father reverend of fighting age during the war between the states can join this bold new century, yes.

After describing for these regulars in great and delectable detail the bread and jam I had, tragically, consumed all of, I asked them about the poor man found dead and exsanguinated to the west of town, asking of myself meanwhile if I wasn’t, in own way, just as bad as Mrs. Grandlin. But no, I told myself. As shepherd of a flock, I needed to be informed on all goings-on that might affect that flock. It wouldn’t do to look out over the Sunday morning crowd and have them whispering to each other about that of which I’m ignorant.

“The west?” California Jim spat in response, disgusted, answering the first of the two bluffs I’d built into my opening bid, for them to correct.

I’ve never inquired after the provenance of California Jim’s name, but assume it has to do either with one or another gold rush or with another of his many former occupations.

“Ex-what, Preacherman?” Sall Bertram mumbled, leaning ahead to spit between his boots into a crack in the porch nearly crusted shut, from all the days he spends there.

“He had been bled, had he not?” I said with all false innocence, looking from one to the other, which prompted them, in turn, to look to each other.

“Your Lutheran god whisper that to you?” Thomlinsen finally said, which struck me odd, as I’d only proffered the possibility of exsanguination so as to be a babe in the fold for them, plucking at rumor and smoke, meaning they could correct me with the actual facts and thereby become authorities.

Men on in their years, whose sole job is to occupy a bench, like to feel important, I know. It’s quite possible I suffer from a liturgical version of this myself.

“I suppose most of his blood did leak out when he were skinned like a hump,” Thomlinsen said for them all, glaring me down as if challenging one so pure of heart to picture something so revolting.

If only he knew.

The depravity of man’s heart knows no floor, and everyone in this hard country has a sordid chapter in the story of their life, that they’re trying either to atone for, or stay ahead of. It’s what binds us one to the other.

I wasn’t there to publicize my own moral failings, howsoever, but to further hone Mrs. Grandlin’s revelation. What I had so far, without asking directly, were “west” and “skinned”—and, now, possibly “exsanguinated,” though that could very well be my misreading.

“To what end do you skin a person?” I asked.

“I seen a man filled with so many Indian arrows in him that he looked like a pincushion in a sewing parlor,” Early Tate said, licking his cracked lips hungrily. “Sixty nine, it were.”

“James Quail?” Sall Bertram either said or asked, it was hard to distinguish.

“Down on the trail,” Early Tate answered with a shrug, yet holding my eyes, perhaps to see if I would challenge him on this.

The “trail” he spoke of was the deep ruts of the Oregon Trail, which he’d famously been a drover on in his twenties. In each retelling, his deeds and exploits become a little more grand, I should note.

I didn’t doubt this pincushion man, though, “James Quail” or no. In the late ’60s he spoke of, and into the bloody decade that followed, I had myself seen similar travesties, that still haunt me in my weaker moments, with only one candle remaining, the town around me long asleep. But you can build a wall around yourself with scripture and faith.

“Like a buffalo, you say?” I asked then, due to their use of the word “hump.”

This question prompted more looks between the regulars. Looks and the shuffling of feet, the rearranging of certain jugs and bottles in this or that jacket. Finally Sall Bertram out and said it, immune as he was to legal repercussions.

“His face was even painted,” he proclaimed, pulling his own fingers downward along his forehead and nose, down to his chin.

“Skinned and then painted?” I asked back, earnestly incredulous at this development.

“The skin on his face was still where it ought’ve been,” California Jim said, forgetting for a moment I was there and instinctively taking a long pull from the bottle nestled against his chest. “Apology, Father,” he added, wiping the back of his mouth with his sleeve.

“Forgiveness comes at a price, and none among us is immune to sin,” I returned back to him, shrugging my thin shoulders and holding his eyes steady in mine, such that more words would have communicated less.

The grin spread among the regulars until California Jim shook his head in mirth and extended the bottle to me. After ascertaining no Puritanical eyes were trained on us, I took the bottle, tipped it up, and let that familiar fire into my chest for the first time since donning these robes, and for a moment I was in my thirties again, and my forties, and the first part of my fifties, swimming in such a bottle as this, looking out at the world, distorted into abomination by the irregular glass, and my own failing eyes, and the syrupy quality of my thinking. And my guilt.

“Preacher!” Thomlinsen cheered, holding his own bottle up.

“Reverend!” Early Tate chimed in, grinning so wide I could see the dark blood between the cracks of his lips.

“Yellow and black,” the former sheriff of Custer County continued, such that I had to picture this “hump,” the skin pulled from his back and presumably his whole torso and possibly his legs and arms, his face painted half yellow, half black.

You can’t guess at what an Indian does, though, much less the why of it. Maybe Franz Boas can, but I’m no Boas. If anything, I’m more Boethius, trapped in my cell on these northwesterly plains, scribbling my earnest inquiries into this log, with hopes of finally arriving at some greater truth.

“Had a little dab of red in the middle!” Early Tate added with a satisfied chuckle, relaxing back into the pew, which creaked with the weight of his pronouncement.

When I looked my inquiry over to him, he waggled his blunt, somewhat red tongue, prompting Thomlinsen to fall into a coughing fit meant to direct us elsewhere.

I had the scent, though, and could make the leap myself, being no tenderfoot.

“His tongue was removed?” I said, awe quieting my voice to a whisper.

“What would be the use of that?” Sall Bertram said back, which I took to be confirmation, and when California Jim made to drink openly from his bottle, the former sheriff stopped him. The message he intended was subtle, but loud enough in this newly spawned quiet. Though I had previously, momentarily, been one of them in the brotherhood of spirits, and of flaunting it in the light of day, now, at this juncture, I was alone again, no longer a drinking companion, never mind that the long pull I had elected to imbibe was still a warmth roiling in my chest, and coursing through my thoughts, making me consider the sacraments of the Eucharist I have unmonitored access to.

“Gentlemen,” I said to them with as much thankfulness and respect and lack of challenge as I could, and proceeded on my way, pretending for their sake that I had only stopped at the lodging house by happenstance, to pay my toll, and was now continuing on to my original destination of the post office, as if I had anyone in the world who might want to send me a letter.

I’m starting my transcription here, pretty much, as this seems to be when things get interesting. I’m trying to solve a mystery, I mean: What happened to Arthur Beaucarne in 1912? I’ve struggled an entry ahead of the transcription above, so I know he had, or planned to have, a series of fantastical conversations with an Indian man known in Montana in the late nineteenth century as “The Fullblood,” but I don’t know yet if this is causation or merely correlation.

And, yes, tenure and promotion committee, I know that this is more a project for a history professor, or someone from Ethnic Studies, American Studies, maybe Philosophy and Religious Studies, even the English Department, but . . . are any of the scholars from those programs related to the subject? That’s my hook, I’m fairly certain. That’s the thing that’s going to get this junior professor a book under contract, and position her on campus for a long and comfortable career.

Like my dad, yes.

Like him, too, I wore a mask and gloves and booties for my work, at least the first time, sitting on my couch, my nose inches from the flickering screen of my laptop, Taz My Cat—full name, there—curled on the cushion over my shoulder. I was holding my breath, too—I was making a connection with someone actually in my blood. Being the lone daughter of a father with no siblings, my family tree has been more struggling vine than anything branching into a generations-wide canopy, so finding this unexpected relative has been nothing short of wondrous. In order to feel closer to Arthur Beaucarne, I even went to campus and loaded up the special-use paper from the back of the supply cabinet, printed the scanned-in images on what feels for all the world like card stock.

Those stiff pages are currently spread out across the dining room and hallway of my apartment, so I can walk along my greatest-grandfather’s last few weeks.

He was never found after his last entry, no, and I admit I’m nervous about getting that far and having to say goodbye to him, watch him recede into history.

Last night I stood on the balcony of my apartment and peered out into the glittering darkness, and I whispered his name, Arthur Beaucarne, and then I closed my eyes, imagined I was hearing the rustle of his thick black robes when he raised his head out there in the vast darkness, hearing me.

As for the ramp to get to the entries in his journal, which I probably would have already laid out were I a historian: in 1912, the Miles City Star was in its second year; Trinity Lutheran Church was in its sixth. Miles City itself had only been incorporated in 1887—two years before Montana itself became a state, and some thirty-five years after Custer County was named that, in memory of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Though the buffalo were long gone from Eastern Montana by 1912, and from North America as a whole, the memory of them blanketing the Great Plains lived on.

It’s 2012 now, as I write this. The anniversary of my greatest-grandfather’s disappearance. I have Lutheran blood in me, surprise. I’d always thought my family must be French a few generations back, possibly some of those French who came down through Canada, to trap and trade furs, but lineage doesn’t mean much, finally, does it?

As for myself, which I should have said at the top of this document: I’m Etsy Beaucarne. Single, white, forty-two. I live on the second floor of an apartment complex where I sometimes see students from my freshman courses on the stairs, and my main source of conversation is my cat, Taz. It’s short for “Tasmanian Devil,” a cartoon character from my youth who was a force of chaos and destruction. You’d have to see the arms of my couch and the lower portions of the drapes over my sliding glass door and the apron of my bed to understand why I named him that.

I love Taz like you love an only cat, though. We’ve been through the fire of grad school together, through two live-in boyfriends, and I’ve bathed him in the kitchen sink when he comes home with his ears torn and his coat matted with blood.

But he means well. His gifts show his true heart, don’t they? The dead birds left on the kitchen floor, which he expects me to cheer for. The mice he deposits outside the bathroom door—always there, I don’t know why. Because it’s “the mouse place,” I guess. Twice, now, there have been moles, one of them still halfway alive, and suddenly wriggling in bed with me. Most recently—and most out of place—a prairie dog, this one completely alive.

Coming in from campus with that stack of printed-up journal pages—so much heavier than I anticipated—I rounded the tall rubber plant opposite the front door, deposited my shoulder bag on the couch, and stepped into the hall, which is when we saw each other, this prairie dog and I. He was a small form framed in the doorway of my bedroom, mired in shadow, but I have to suspect I was as well, my giant form blotting out the overhead light.

Slowly, this prairie dog stood up onto its hind legs and considered me, tasting my scent on the air, and then it charged down the hall in its dromedary way, its yellowy, protuberant incisors meant only for seeds and stalks, the rational part of me knew, but this wasn’t a rational moment.

I yipped, stepped neatly up onto the couch, and hugged a throw pillow to my chest, but this prairie dog never crashed out into the living room. After what felt like an hour but was probably two minutes, I gingerly stepped off the couch, still clutching that pillow, and peered down the hall.

It was empty.

“Taz?” I called.

He didn’t come, even when I broached into the kitchen, used the electric can opener on his food, a grinding sound he can’t resist.

Two hours later, he thumped onto the balcony in his usual way, as if dropped from a low-flying blimp, and pushed his head through the cat door to look around like always, as if confirming this was the right apartment.

“There you are,” I told him, and he slinked in.

He was, this time, coated in what I took to be antifreeze, about which I knew not to even ask. After he kindly left radioactive footprints on some of the journal pages, which were in their first configuration on the couch, I took him to the kitchen sink, got the good Dawn soap, and lathered him up against his will.

“I found what you left me,” I murmured to him, scrubbing his coat clean, and for a moment I didn’t want, my back straightened, because the floor had creaked behind me, exactly as if Arthur Beaucarne had heard me just thank him for what he left me—his journal—and had decided to step out of the ether, start mumbling a prayer in some dead tongue.

I didn’t look around, though. You can’t look around, every time you think you’re not alone.

Once you start, you never stop.

Instead I’m just going to huddle here over my laptop, burn my eyes out trying to make sense of hundred-year-old script so light it’s hardly there, and type it in after this the best I can, for however long it takes.

Here goes.

The Absolution of Three-Persons March 31, 1912

HE WAS THERE again today, the Indian gentleman.

This is only his second Sunday to attend, but in a congregation as tight knit as mine, I find a face I don’t know out in the chapel to be . . . not worrisome, I should think of it as a gift, as another chance to fulfill a missionary’s duty, and thereby inch myself that much closer to redemption. But his presence is disconcerting—through no fault of the Indian’s own. It’s as if he’s a face from either the past or my past, it’s hard to decide which he might unintentionally represent.

Through the whole of my sermon, I longed to lob a pebble to his isolated pew at the back, to see if he would snatch that pebble from the air at the last moment, and then hold it in his lap for the rest of the service, worrying it between his fingers. And I would follow that pebble’s journey further as well, to see if he let it fall alongside his right leg as he exited. Or maybe I would even follow him to wherever he’s found or made lodging, to see if he examines that pebble by firelight, and perhaps slips it into the medicine pouch all of his breed carry on their person, close to their skin.

I would like to have that between us, I think. I would like to be part of the secret totem beneath his shirt, held close and important to his chest forevermore.

As for this Indian’s appearance, well, he’s Indian. The red skin, the broad face and wide nose, the hatchet cheekbones, that grim slash of a downturned mouth. A distinct amusement to his eyes about our proceedings in this house of worship, but a harsh, embattled cast to his face as well, speaking of many trials and tribulations, much hardship and loss. His hair is long and oily and black, suggesting he’s not a product of Jesuit school, which is in contrast to the floor length black clerical robe he wears, about whose provenance I won’t even hazard a guess, as it may involve some Man of the Cloth’s remains moldering in a gulch.

As for his intention with arraying himself in this raiment, I have to think it’s easily explainable. Surely, in wanting to come to a white man’s church, this Indian gentleman thought it vital to attire himself after the same fashion he has to have seen white men going to church in. A failure to understand the hierarchy in these church walls, where the man behind the pulpit and he alone dresses suchly, is beneath having to excuse. Instead, I take this mimicry as the highest honor, and I’m thankful for the childlike innocence with which it’s delivered—let the little children come to me, yes.

However, that robe is the only thing childlike about this Indian. While it’s difficult to hypothesize the age of someone whose kind I’m not intimately associated with, I would put this gentlemen between his early thirties or late forties—well past the age where he would have been part of a raiding party in decades past, when such things were yet occurring, but, at the same time, he’s perhaps older than individuals of his race usually make it to. I detect no silver in his hair as of yet, but I also know that the grey comes late among his people.

And, it’s beneath saying, but the Indian’s face is cleaned to shining, beardless and not mustachioed, and his hair, though long and heavy, is drawn back, which I take as a token of respect, as when a cur pastes its ears back along its skull in hopes of passing without drawing a kick or harsh word.

This is as well as I can draw him in the pages of this newest volume of my phrenic peregrinations. His bearing and posture this Sunday was the same as last, I should add—shoulders square, spine straight. I was initially discomfited with how his eyes tracked my every movement, as if I were one of his wags-his-tails, which I understand is his people’s word for “deer,” though of the big eared variety or the smaller variety with that white flag of a tail, I can’t yet ascertain. But of course, his watching me like a deer he would roast on a spit actually makes perfect sense. Presumably familiar with enough English to accomplish simple commerce, he must be mystified by the Vater tongue I deliver my sermons with. His attentiveness, therefore, is but evidence of the concentration he trains on my words.

When everyone else reached for one of our few hymnals, he plucked one up as well, a strange flower to him, not understanding that the tome he held before him for the singing portion of the service was in fact a Bible—more evidence of his lack of formal education. Rather, he was surely educated in the Edenic hinterlands, where he can read the fowl and the fauna more closely than I can the very Scripture.

More interesting than his looks or comportment, though, are his reasons for attending my service. Is he hoping to suspend a delicate bridge from his people to mine, and so foster a unity where there’s only been decades of division? Did he, in his youth, see a wagon train assembled before a Man of the Cloth, and wonder about the power wielded by that man at the front of the congregation? Has he heard tell of the white man’s religion, and wants to see where it might line up with his inborn one?

Now that we’ve shared private and extended discussion over things so fabulous as to themselves be fables, I can speak better as to his reasoning, his reasons, but, reciting my service that first and this Sunday, I confess to having been mainly agitated about whether or not he was only here for a meal. If so, he would have had to make do with a thin white wafer. I’m ashamed to say that, during the Eucharist, I positioned myself so as to observe him. But, both Sundays, he limited himself to but a single wafer, glaring against his dark skin, that hand rising to his mouth and then coming back down, his eyes holding mine the entire time, as if to prove to me that the holy sacrament wouldn’t smoke on his pagan tongue.

I would have allowed him more and of more substantialness, of course, had he but asked or made his hunger known. Had he stayed after that first service, I would have led him to my parsonage and broken bread with him—not Mrs. Grandlin’s, that wasn’t to me yet. But, had he been there upon its arrival, then we surely would have shared in that repast. I may be gluttonous in private, but in fellowship, I hope to set a better example.

When I would have extended such fellowship to him last Sunday, however, he stood with the rest of the congregation, holding my eyes across the congregants’ as yet hatless heads, and I felt for all the world as if he had been there to judge me. Were I speaking to myself as I speak to my parishioners, I might portend that those who fear the presence of a judge may very well be carrying a secret burden of guilt they hope to unload. Yet, to be judged by an Indian, here in the new century? To have this twentieth century called to task by its predecessor?

Your fantasies know no limit, do they, old man? Leave anyone too long alone with his own thoughts, and every possibility will be not only explored, but poked and prodded until it raises its shaggy head, settles its lidless eyes on you. Such is the price of isolation, and that mulling that never ceases. Though of a different order, I feel I’m nevertheless a monk in his bare cell, with only a quill and scroll to converse with.

After this afternoon’s proceedings, I suppose I now have this Indian to converse with as well, if I’m willing to lean in closely enough to hear his subdued voice.

But I was documenting his first appearance last week, which I neglected to write about that Sunday, I think due to my dim hope that he was but an aberration in my weekly routine, not worthy of committing ink to.

And even still I explore the fullness of language and distraction in the recounting, instead of daring to look directly at this Indian. But my ink pot is full, this candle is as yet tall, my back doesn’t hurt too much yet, my nerves seem intent on continuing to twitch this nib across these evenly lined pages, and no one is immediately waiting for me to save their soul, so, what harm can there be? “Soldier on, Pastorbrotherman,” the men on the porch at the lodging house might urge me.

It’s to them I ascribe blame for the chalice of communion wine half in and half out of this candlelight. But, better it not turn to vinegar. That would be the actual pity.

This Indian, however, whom I know I need to find the strength to look directly at, at least on this unblinking page.

That first Sunday of his attendance, upon the service’s conclusion, the Spirit moving through the congregation in a way that always fills my chest, he rose with a quickness that aged him down a full decade. Though when I would have forded the bodies to hold his brown hands in mine and look meaningfully into his eyes, he turned neatly away, lowering his face into the peculiar darkened spectacles I’ve seen travelers on the train platform wearing, to look directly into the endlessly bright sky.

He did look back once, confirming the pursuit he seemed to expect, his wildborne instinct keenly aware of such things, but by the time I reached the back of the chapel in my limping manner, this Indian gentleman was striding away into the daylight, his Jesuit robe swinging around his long, purposeful strides, his hands tucked into the cuff opposite themselves, the dogs of Sunday morning giving him wide berth, which is the first time I’ve seen such a phenomenon in my time in Miles City. But surely it’s the bear grease in his hair that forces them to keep their distance, or the scent of tragedy on his skin, or that he was keeping to the shaded side of the street, where the warmth isn’t. Or maybe, not seeing his eyes, they don’t know if he watches them or not, so can’t guess his next sudden movement, can’t anticipate his intentions. To them, he’s a berobed, glassy eyed creature whose predilections are yet a mystery.

Over the intervening week, I convinced myself that in a place this far west, I should steel myself for visitors such as him, and not make of his presence anything portentous.

His sullen presence at the back of my church was a solitary event, I assured myself, a random occurrence. It tokened nothing. But then, this morning at Service, he was back again.

When he stepped in at the last moment and settled himself into the last pew at the back and sat upon the aisle like a station his own, so there was no one between himself and me, I admit I lost my place halfway into the recitement of Our Father, which I know now as well as I know the contours of the roof my mouth.

Such is weakness. Such is blasphemy.

My penance will be long and just, I know. And it starts late in my life, with, I can tell now, this Indian gentleman, which I know is probably the first time one of his race has been referred to as such in ink.

This time, instead of staring into his darkened spectacles and folding himself into the busyness of the Sunday afternoon bustle, he remained in his seat while the congregation filed past, the women giving him wide berth, the men’s eyes hardening upon realizing this relic they’d evidently been sharing worship with. Some of them, I know, as yet harbor memories of stock slaughtered, of horses stolen in the night, of women foully mistreated, children snatched away to have their pasts erased, replaced with a wildness they would use to fight their own kind when given the slightest chance.

But there was violence done on both sides, I would tell my parishioners consolingly. And there’s the Lord’s forgiveness, to wash all that away, start anew, so we can step together into this new century, absolved of the past, never mind what bloody footprints our boots yet leave. Walk far enough away from the scene of that violence, and your boots are like unto your neighbor’s, shriven clean and born again.

As is my custom at the cessation of a Sunday service, I stepped out of my station as pastor, became an usher for everyone wading out into the bright sunlight, which is of course just a shepherd of different variety. And then I was alone in the dark, empty chapel with this Indian gentleman.

His stillness was offputting, if I’m to be strictly honest.

So as not to scare him away with interrogation or attention, I set to tidying the pews, my eyes flicking periodically to him. Usually I’m wont to hum with this task, so as to allay the oppressive silence, but in deference, I practiced restraint.

Did I think he was going to rise up, bury a stone tomahawk in my back? What I didn’t expect was for him to finally say it, and in clear English, his voice exactly as deep as I was expecting in my heart: “Father.”

I stilled my nerves, stood from the pew at the front I was currently pretending to straighten, then straighten again, and turned to him, my fingertips holding each other at my waist, my posture more pensive than a man of my years and station should adopt, but you can’t always make yourself stand as you want.

“Pastor,” I corrected him, attempting to strip the schoolmarm from my voice.

The Indian gentleman nodded once, accepting “Pastor” without question, but then he looked up to me about it, his eyes glittering with something, and said, as if correcting a mis-statement, “Three-Persons.”

“Three Persons?” I asked back, about myself.

“Father, Son, Creator,” he said, enumerating with his long brown fingers.

I didn’t correct his conception of the Trinity.

“Do you mind, Three-Persons?” he asked then, holding his dark spectacles out between us, proffering both them and this new and complimentary appellation for a simple pastor. I let the name settle around me like a mantle, then commenced to prizing into what he might mean with these dark spectacles. When I could get no mental purchase—did he want me to polish them?—he clarified with, “This . . . the brightness in here.” He moved his fingers back and forth by his temple, by his right eye, to mime the brightness so troubling him.

I looked around at the chapel I keep intentionally dark, so as to stymie conversation and focus attention to the front. I can’t always direct the inner lives of my flock, but I can, in such small and indirect ways, control the bearing of their exterior selves. In quietness begins devotion, does it not?

“Of course not,” I said in reply to the Indian gentleman, and stepped two pews closer, my hands still clasped in front of me.

He lowered his face into the dark spectacles and looked up at me through them, and I have to imagine that, to him, in the darkness of the chapel, I was but a shadow.

“I have an illness,” he explained to me, tapping the side of his spectacles, and I nodded, stepped two pews closer.

“I knew a miner in Missouri who couldn’t tolerate being indoors,” I said in my gentlest, most understanding tone. “Not since the roof over a vein he was working collapsed in on him and his fellow workers.”

“Like a big-mouth who wants for water but barks at it instead of drinking,” the Indian gentleman said, as if to establish for me that we were, in fact, in communication.

“A . . . ‘big-mouth’?” I was compelled to ask, however.

The Indian gentleman bored his gaze into a point above my shoulder, then nodded, seemingly to himself, and corrected with, “Wolf, as you would say it.”

“Ah, a mad wolf, you mean,” I said, taking the olive branch he would extend. As if talking to a child, I mimed foam coming from my lips.

The Indian gentleman grinned slightly to see me do this, looked away so as to let me preserve my dignity, and said, “Not the Mad Wolf I knew, no. Mad Wolf was Hard Topknot in my youth, who always stayed back during a horse raid, until his sits-beside-him wife finally walked away from him, telling the rest of the band that if she were a fine horse, he wouldn’t have the nerve to follow her, lead her back to his lodge.” The Indian gentleman grinned in a small way to be relaying this, suggesting it was a sort of running joke. “She was right,” he added, which was perhaps the part in this retelling where those of his breed gathered around the fire in one of their tipis would nod and chuckle to themselves as one.

And I confess here that, while what he relayed to me held interest, what was even more fascinating were his ancient terms, only barely translated for me. “Sits-beside-him wife,” “big-mouth” and their coyote brethren the “little big-mouths”—it’s all so rational and easy, so descriptive and childlike. Over the course of our afternoon, this ancient language would pile up and up like a mountain of buffalo skulls—pardon, “blackhorn” skulls.

“Real-bear.”

“Long-legs.”

“Coldmaker.”

“Sticky-mouth.”

This last one I take from context to be not quite a bear but more than a weasel, perhaps with a mouth characterized by saliva?

Regardless, I hope to preserve these peculiarities on the page as best I can, as this may be their last uttering, the Indian gentleman’s kind walking into the sunset of their day.

“So what brings you here today?” I asked him then, to prove to him that we were communicating clearly enough that I could sense he had more to say.

The way he, in response, stared past me, his head moving back and forward ever so slightly, as if he were on the deck of a steamboat in calm water, was, I believe, evocative of the difference in our two peoples. In his lodges and around his kind’s fires, each word and each answer is surely considered before being spoken, so as to not utter anything unnecessary. To one who often listens to himself at the pulpit and wonders who it is speaking, and what it is he’s saying now, this is a thing uncommon indeed.

As a pastor with some experience listening to his flock, however, I know I need must comport myself in these conversations by his guidelines and needs, lest he become impatient and remove himself back to his own people, denying himself the grace of God which I would so willingly share, and instruct him toward.

“What brings me here today,” he repeated in the lips shut way he speaks, as if this question were a knot too complicated to loosen with a mere reply.

Behind his dark spectacles, his eyes closed tightly, I could tell, and I was able to study his face more closely than that view afforded me from the pulpit. I could tell now that his face and cheeks and jaw, while scrubbed to shining, were in fact pitted, telling of some encounter with the pox, in which he surely writhed for days in a flea ridden buffalo robe, some medicine man chanting and drumming over him and wafting various smokes, never knowing how useless those ancient practices were for this modern affliction.

When the Indian gentleman’s eyes opened again, I let mine slide to the side, to give the lie that I hadn’t been taking the opportunity to stare like a child.

He was as yet blinking from the brightness, however.

“Here,” I said, and rushed around the chapel, pinching the few wicks out and carrying back the lone remaining candle, but being sure to place it far enough from us that it was less than the coals after a fire on a dark night, lending but the slightest underglow to our faces, the shadows of the hands I clasped between my knees probably exaggerated on the unpainted ceiling above us, but I dared not look.

“Thank you, thank you,” the Indian gentleman said, pulling the spectacles from his face ear by ear, which required more head movement than I would have anticipated, the legs or arms of those spectacles being hooked nearly into circles at the back.

The spectacles folded neatly into one of his sleeves, which made me wonder what else he might have hidden up there.

“What I wish is to confess, Three-Persons,” he said at last, holding my eyes in his, and, this being the first time I was seeing his eyes at this near proximity, I found myself mesmerized, like unto he held some animalistic sway over me. As I’d seen from afar, his eyes were inky, undifferentiated black, but the middlemost parts, usually a dot not dissimilar to a large period, were engorged as I’d only seen before in the dead and eternally resting.

Of course he needed it dark for his confession.

“You don’t have a box we can sit in?” the Indian gentleman asked then, squinting around the chapel for the confessional booth. Then he corrected himself with, “A wooden closet we can speak in through the—the . . . ?”

He held his hands out in a plane between us, fingers spread across each other to simulate a series of chinks or holes, such that I knew he’d seen the latticework Catholic confessionals have.

“This is a Lutheran house of worship,” I said as delicately as I could, as presuming him to know the varieties of the Christian faith would be uncharitable of me—and this on a day I’d just delivered a sermon about the Samaritan. “But yes, after reading the Commandments, we can go to the altar rail and . . .”

I swept my arm to the front of the church to show where I meant.

“You can unburden yourself there, if you so desire,” I assured him, sensing either reluctance or a failure to comprehend—which, I couldn’t tell.

“Can we do it here?” he said, staring at the floor between his polished black boots, which I could see now that his Jesuit robe had ridden up his lower leg from having been seated for so long. The boots were, unless I mistake them, of the cavalry variety, from when the cavalry was more needed. It put me in mind of the days when Indians would dress themselves up in the finery of their victims, both male and female.

I settled into the pew in front of him and to the side a bit, turning to lean a single arm over my backrest and thus indirectly face him, so as to not threaten this penitent with proximity, or challenge him, thus, in the limited way available, creating the privacy of the confessional booth.

“Of course, of course,” I said. “What do I call you?” I asked then.

He nodded as if agreeing that this, indeed, was the place to start.