Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

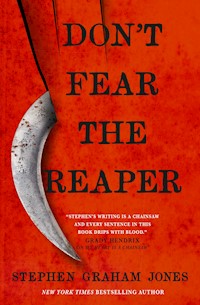

Jade Daniels faces down a brutal serial killer in his award-winning and pulse-punding tribute to the golden era of horror cinema and Friday the 13th from the New York Times-bestselling, multiple-award winning Jones. Four years after her tumultuous senior year, Jade Daniels is released from prison right before Christmas when her conviction is overturned. But life beyond bars takes a dangerous turn as soon as she returns home, when convicted serial killer, Dark Mill South, seeking revenge for thirty-eight Dakota men hanged in 1862, escapes from his prison transfer into a blizzard, just outside of Proofrock, Idaho. Dark Mill South's Reunion Tour began on December 12th, 2019, a Thursday. Thirty-six hours and twenty bodies later, on Friday the 13th, it would be over.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 650

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Motel Hell

Dark Mill South

Scream

Her Name Was Jade

Friday The 13th

The Second Coming

Silent Night, Deadly Night

A History of Violence

Black Christmas

What Rough Beast

The Burning

Hell Night

It Follows

Trigger Point

Happy Death Day

Slasher 102

Just Before Dawn

The Final Terror

Acknowledgments

“The ultimate final girl. Bruised, battered, bleeding but never broken. Dark Mill South has no idea what he’s hit. Delivering characters as riveting as an axe to the face and surprise reveals like body blows, Don’t Fear the Reaper is another bloody triumph.”—A. G. Slatter, author of All the Murmuring Bones and The Path of Thorns

Praise for Stephen Graham Jones

“Stephen’s writing is a chainsaw and every sentence in this book drips with blood, every paragraph is clotted with skin, and every period is a bullethole. He makes me feel like an amateur.”—Grady Hendrix, New York Times bestselling author of The Final Girl Support Group

“A homage to slasher films that also manages to defy and transcend genre. You don’t have to be a slasher fan to read My Heart is a Chainsaw, but I guarantee that you will be after you read it.”—Alma Katsu, author of The Hunger and The Fervor

“Brutal, beautiful, and unforgettable, My Heart Is a Chainsaw ... a bloody love letter to slasher fans, it’s everything I never knew I needed in a horror novel.”—Gwendolyn Kiste, Bram Stoker Award-winning author of The Rust Maidens

“Stephen Graham Jones can’t miss. My Heart Is a Chainsaw is a painful drama about trauma, mental health, and the heartache of yearning to belong... twisted into a DNA helix with encyclopedic Slasher movie obsession and a frantic, gory whodunnit mystery, with an ending both savage and shocking. Don’t say I didn’t warn you!”—Christopher Golden, New York Times bestselling author of Ararat and Red Hands

“An easy contender for Best of the Year ... It left me stunned and applauding.”—Brian Keene, World Horror Grandmaster Award and two-time Bram Stoker Award-winning author of The Rising and The Damned Highway

“Jones masterfully navigates the shadowy paths between mystery and horror. An epic entry in the slasher canon.”—Laird Barron, author of Swift to Chase

“An intense homage to the classic horror films of yore.”—Polygon

“At once an homage to the horror genre and a searing indictment of the brutal legacy of Indigenous genocide in America, Stephen Graham Jones’ My Heart Is a Chainsaw delivers both dazzling thrills and visceral commentary... Jones takes grief, gentrification and abuse to task in a tale that will terrify you and break your heart all at the same time.”—Time

Also by Stephen Graham Jones and available from Titan Books

THE ONLY GOOD INDIANS

MY HEART IS A CHAINSAW

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Don’t Fear the Reaper

Print edition ISBN: 9781803361741

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803361758

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: February 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Stephen Graham Jones 2023. All Rights Reserved

Stephen Graham Jones asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Wes Craven: we miss you

The killer is with few exceptions recognizablyhuman and distinctly male.

—Carol J. Clover

MOTEL HELL

It’s not really cool to play Lake Witch anymore, but that doesn’t mean Toby doesn’t remember how to play.

It started the year after the killings, when he was a sophomore, and it wasn’t a lifer who came up with it, he’s pretty sure, but one of the transplants—in the halls of Henderson High, those are the two main divisions, the question you always start with: “So… you from here, or you’d just get here?” Did you grow up here, or did you move here just to graduate from Henderson High and cash in on that sweet sweet free college?

If it turns out you’re from Proofrock, then either you were almost killed in the water watching Jaws, or you knew somebody who was. Your dad, say, in Toby’s case. And if you’re the one asking that question? Then you’re a transplant, obviously.

The reason Toby’s pretty sure it was a transplant who came up with the game is that, if you’d lived through that night, then the whole Lake Witch thing isn’t just a fun costume.

But it is, too, which is what the transplants, who had no parents dead in those waters, figured out.

The game’s simple. Little Galatea Pangborne—the freshman who writes like she’s in college—even won an award for her paper on the Lake Witch game, which the new history teacher submitted to some national competition. Good for her. Except part of the celebration was her reading it at assembly. Not just some of it, but all of it.

Her thesis was that this Lake Witch game that had sprung up “more or less on its own” was inevitable, really: teenagers are going to engage in courting rituals, that’s hardwired in, is “biology expressing itself through social interaction”—this is how she talks. What makes Proofrock unique, though, is that those same teenagers are also dealing with the grief and trauma of the Independence Day Massacre. So, Galatea said into the mic in her flat academic voice, it’s completely natural that these teens’ courting rituals and their trauma recovery process became “intertwined.” Probably because if life’s the Wheel of Fortune, then she can afford all the letters she wants.

What she said did make sense, though, Toby has to admit.

The game is all about getting some, if you’re willing to put in the legwork. And, as Galatea said to assembly, the elegance is the game’s simplicity: if you’re into someone, then you do a two-handed knock on their front door or the side window of their car or wherever you’ve decided this starts. You have to really machinegun knock, so you can be sure they get the message, and will definitely be the one to open that door. Also, knocking like that means you’re standing there longer than you really want, so you might be about to get caught already.

But, no, you’re already running.

And?

Under your black robe, you’re either naked or down to next to nothing, as the big important part of the game is you leave your clothes piled in front of the door. Galatea called this the “lure and the promise.” Toby just calls it “pretty damn interesting.”

Which is to say, just moments ago he got up from the ratty, sweated-up queen bed at the Trail’s End Motel at the top end of Main Street, his index finger across his lips to Gwen, and pulled the dull red door in to find a pair of neatly folded yoga pants and, beside them, one of those pricey-thin t-shirts that probably go for ninety bucks down the mountain.

He looked out into the parking lot but it was all just swirling snow and the dull shapes of his Camry and Gwen’s mom’s truck. Idaho in December, surprise. One in the afternoon and it’s already a blizzard.

“Who is it?” Gwen creaked from the bed, holding the sheets up to her throat just like women on television shows do. Toby’s always wondered about that.

Another part of the game is that, if you don’t give immediate chase, then this particular Lake Witch never knocks on your door again. “Message received,” as Galatea put it, because “menacing the object of your affection while disguising your identity is… kind of creepy?”

It was the first laugh she got at assembly that day.

“Message received…” Toby mutters to this Lake Witch, kneeling in his boxer briefs to touch these yoga pants, this expensive shirt, as if his fingertips can feel the body heat from whoever was just wearing them. Who was just standing right here where he is, slithering out of her clothes under cover of a robe—and in minus whatever the temperature is.

The question, of course, is does he leave Gwen in the room to chase another girl through the snow?

It’s not really a question, though. This is the game, isn’t it? It’s not about convenience. It’s about opportunity.

“Gonna get a coke,” he mumbles back into the room, and steps out, just managing to reach back in for his letterman jacket. It’s against the rules—you have to give chase exactly as you are, no tying your laces, no brushing your teeth, no pulling your good pants on—but he’s already freezing.

Gwen calls something to him but the door’s already shutting, catching, latched.

Now he’s alone under the second-floor balcony or walkway or whatever it’s called. Galatea would know. “Parapet?” Toby chuckles, zero idea what that word’s doing swimming around in his head. English class, maybe? Some movie?

Doesn’t matter.

What does are the footsteps in the snow, already rounding off in the icy wind.

“This better be worth it!” he calls out into the parking lot.

It feels like he’s the only person in the world, here. Like he’s standing on top of the world.

Everybody smart, which is everybody but him and this Lake Witch, they’re inside where it’s warm. Anybody outside, they probably have their winter gear on, and, for this kind of storm, goggles, and maybe a defibrillator.

Toby thrusts his hands up into his armpits, hunches his head as deep into the no-collar of his jacket as he can, and steps out into the cold.

When he doesn’t come back with a coke fresh from the machine, Gwen’ll know something’s up, sure. But Toby’s already got his lie ready: he thought he had change in the jacket. Just… Gwen’s not exactly stupid. Granted, she just moved here this year, for the scholarship, and the Lake Witch game had pretty much run its course by then, meaning she didn’t recognize its signature knock, but still.

If he’s got a line of shiny-wet hickeys coming down from his neck? If his mouth is smeared with some other girl’s lipstick?

Gwen’s big city, but she’s not that big city.

If you’re a shark, though, you keep moving, don’t you? Keep moving or die. That’s been Toby’s mental bumpersticker ever since the massacre—a strict policy of constant movement means that bad night in the water gets farther away with every day, with every swish of the tail. Or—this is the motel—with every piece of tail. Galatea should write something about that, really. The principal’s basketball-star son landing on “shark” as his spirit animal? “Really? Is this, pray-tell, maybe the same shark that was on-screen when your principal-dad was dying in the water?”

Probably, Toby knows.

You do what you have to do.

And you keep moving, from Penny last week to Gwen this week. And now… now whoever this Lake Witch is going to be.

Wynona F, emphasis on that last initial?

Oh yeah. Yeah yeah yeah.

He’s glad this game is back. Who cares if it’s already old. It’s also forever new. And no, Henderson High, having a Terra Nova princess read it to assembly didn’t quite kill it, thanks. It did pull it into the spotlight, but it didn’t wither.

Neither is Toby—though he does reach down, check to be sure.

Good to go.

The cold doesn’t matter to a lifer, does it? To someone born to this elevation, to these winters?

He does have to turn his back to the wind, though, to keep it out of his jacket, and whoever the Lake Witch is tonight wasn’t expecting that, evidently—a ragged black form slips out of his peripheral vision, into the white.

Too fast to tell for sure if it’s Wynona.

“Here I come!” Toby calls out all the same, and like that the chase is on.

Galatea’s explanation to assembly was that all the running after each other is foreplay, is hunter-prey seduction: the blood’s flowing, the breathing’s already deep, and, if this Lake Witch knocked at the right time, then the one who finally catches them is probably in some state of undress. Just like they are under that slinky robe.

“Convenient, yes?” Galatea said to assembly—her second laugh.

As always, there were bowls of no-questions-asked condoms at the two doors out of the auditorium that day.

As always, someone had already dropped an open safety pin into each bowl.

Hilarious.

And, speaking of: Toby pats his pockets, comes out with… Visine, of course. A blue pen, okay. His wallet, damnit. Unless he stashes it out here, Gwen’ll know he had money for the machine.

In the other pocket, though—yes. Three rubbers.

He counts in his head, and… yeah. That’s how many he should have left.

He puts everything back into his pockets, just catches a hooded face watching him from the vending machine hall.

He’s there in a flash, his feet ten degrees past numb, but this Lake Witch, who did keep her boots on, it looks like from her tracks, has run all the way through to the other side of the motel.

Instead of falling for that like a noob, Toby backs up, jogs to the front, because that’s the only way you can come back, if, say, you think your pursuer is coming up the vending machine hall.

“This better be worth it, it better be worth it!” Toby calls out into the storm, but he’s grinning wide, too.

Until Gwen opens the door of their room.

“My money blew away!” Toby says back to her, bending like trying to catch a dollar scraping across the snow.

“I’ll give you another!” Gwen calls back, hugging herself against the cold.

And… no.

But yes: she’s seeing the yoga pants and shirt she’s nearly stand-ing on.

“What?” Toby thinks she says. It’s what her body language is saying anyway. What her eyes are beaming across.

You don’t understand, he wants to explain to her. I have to see who this is. She won’t come knocking again.

All of which translates down to I’ll never be this eighteen again, he knows.

He takes a step toward her, which is when he becomes aware of… of some massive shape in the parking lot. Like a great black wall fell out of the sky, planted itself across the lines.

“What the hell?” he says to himself, and looks over his right shoulder for the chance of this Lake Witch slashing up beside him, touching his side before slipping away again.

And there’s Gwen, holding those clothes up now, inspecting them.

Recognizing them? Girls can do that, can’t they?

And—and… and now this whatever-this-is in the parking lot?

It’s too much.

Toby doesn’t want to get too far from the motel, but this is a mystery he can solve in four or five steps, he’s pretty sure.

He shuffles out, his teeth starting to chatter, and it’s… a trash truck?

A big gust swirls hard little crystals of snow up into his face, his eyes, his lungs, and he spins away from it all, shakes his head no, that he’s just going to go back to the room, back to Gwen. That if Wynona’s into him, great, fine, wonderful. But another time, girl, please. Can’t she see he’s otherwise occupied?

Doesn’t she know how freaking cold it is?

He balls himself as small as he can to take less punishment from the wind, which is when… something hot happens. Hot and fast.

At first it doesn’t even make sense to his primitive shark brain.

Part of the game, the “advanced version” as Galatea had called it, making it all super boring and academic, was the Lake Witch dashing past, “counting coup” on her or his intended’s shoulder—“part of the dance,” Galatea called it, getting zero laughs, this time.

“Coup” is a Native American thing, she then slowed down to tell them all, being kind of judgy about it, like she was insulted that this even needed to be said out loud.

In the parking lot two months after that day at assembly, Toby looks up to the blinking neon sign, the giant dying Indian on his giant tired horse, and then, to be sure he felt what he thought he felt, he looks down to his hands, opening at his waist.

They’re not just red with the light leaking down from the Indian, they’re red with his blood, and they’re holding his, his—

He shakes his head, falls back.

He’s holding his intestines, his insides, his liver and pancreas and gall bladder and whatever else there is, and his hands are so numb they don’t even know what it is they’ve caught.

He pushes them away as if getting them out of his vision will mean they’re not really happening, but that just pulls more out, and they’re glisteny and lumpy and slick and getting away fast, and he feels a warm hollowness inside that he’s never felt before—it’s the wind, blowing into him for the first time, because his gut is now an empty cavity.

He falls to his knees, trying to gather himself to himself, and when he looks up again, the giant neon Indian is looking right down at him.

It flickers once, comes back stronger, redder, and then it dies all the way out.

Toby Manx goes with it.

DARK MILL SOUTH

In the summer of 2015 a rough beast slouched out of the shadows and into the waking nightmares of an unsuspecting world. His name was Dark Mill South, but that wasn’t the only name he went by.

Cowpoking through Wyoming, working the feedline as they used to call it, he’d been the Eastfork Strangler. Not because he ever hung his hat in the Eastfork bunkhouse or rode their fences, but because he’d somehow come into possession of one of their 246 branding irons, and had taken the time with each victim to get that brand glowing red, to leave his mark.

For that season he’d been propping his dead up behind snow fences, always facing north. It wasn’t necessarily a Native American thing—Dark Mill South was Ojibwe, out of Minnesota—it was, he would say later, just polite, after all he’d put them through.

His manners extended to six men and women that winter of 2013.

Come spring melt, the Eastfork Strangler lobbed his branding iron into the Chugwater and drifted up into Montana, where the newspapers dubbed him the Ninety-Eye Slasher. It was supposed to have been the “I-90 Slasher,” since Dark Mill South’s reign of terror had extended up and down I-90, from Billings to Butte, but the intern typing it into the crawl on the newsfeed had flipped it around to “90-I.” By that evening, “Ninety-Eye” had gone viral, and so was another boogeyman born.

The “slasher” part was close to right, anyway: Dark Mill South was using a machete by then. With it he carved through eleven people. He was no longer being polite with them. According to the one interview he’d ever supposedly given, Montana had been a bad time for him. He didn’t remember it all that clearly.

Next it was the Dakotas, where he was known as the Bowman Butcher, responsible for eight dead at Pioneer Trails campground over a single weekend, and then two weeks later in South Dakota he became the Rapid City Reaper, who didn’t use a bladed weapon at all, but hung his five victims by the neck, one per month.

It was those five victims who got the authorities piecing his history together—what could be his history. The campground this “Butcher” had sliced through in Bowman, North Dakota, was 160 miles directly north of Rapid City, and murders happening two and a half hours from each other, with major arteries connecting them, and on successive months… this couldn’t be the same killer, could it?

At which point someone probably unfolded the map, to see what roadways fed into Bowman. To the east it was smaller and smaller farming communities, and no major highways or interstates until I-29, which was nearly Minnesota. And there had been no unaccounted-for bodies turning up over there. Nothing to suggest a killer prowling the rest stops and truckstops.

U.S. Route 12 west out of Bowman, though, connects with I-94 just over the Montana state line, and, although called “94,” it’s really what I-90 should be, if it hadn’t taken a sharp turn south. And there were definitely bodies piling up alongside I-90. Or, there had been. Two months had gone by since the last one turned up in pieces. Either the Ninety-Eye Slasher had been locked up for some minor offense or he had hung up the white pantyhose he’d been using as a mask and moved on to other pastures, other victim pools.

A campground in North Dakota, perhaps? And then Rapid City?

While Dark Mill South hadn’t used a machete on those eight campers, the felling axe he did use to deadly effect that weekend had, according to forensic analysis, been swung from the left, not the right. Just like the Ninety-Eye Slasher’s machete. And those brands the Eastfork Strangler had burned into his victims were all deep, mortally deep in most cases, but autopsy showed that they were just a smidge deeper on their right side.

Since only ten percent of people are left-handed and less than 0.0008 percent are serial killers, then, statistically speaking (ten percent of “0.00008”), it was less likely that the Eastfork Strangler and the Ninety-Eye Slasher and the Bowman Butcher all just “happened” to be left-handed than it was that they were actually the same killer, adopting different methods and rituals with each change of location, so as to not attract an interstate task force.

That task force was forming all the same.

However, this Rapid City Reaper wasn’t using a bladed weapon or a branding iron that could give away his handedness. And instead of a sustained killing frenzy involving stalking and masks and campgrounds, he seemed more deliberate with his victims, as if he was feeling out a way to extract more meaning from the act.

How he staged his series of hangings through the suburbs of Rapid City from December 2014 through April of 2015 was to allow his victims metal stools to stand on, so as to take their body’s weight off the rope around their neck. But these stools, which the Rapid City Reaper was bringing with him, were all metal with rubber feet, so he could open up an outlet on the wall—always the north wall—and splice into that current, leave this stool circulating with blue fire.

The result was that the stool these people could stand on to take the pressure off their neck was sizzling hot, would arc up and down through their hanging bodies. Without shoes or socks, just touching that stool would cook the soles of their feet, a show the Rapid City Reaper would observe while eating cold leftovers from the victim’s refrigerator, the crumbs of which he was leaving either carelessly or due to overconfidence.

Since there were no wounds on these hanging victims other than their cooked feet and crushed windpipes, where the authorities had to look for the telltale signature they needed was the splices in the wires used to pass the current. As it turned out, these copper unions had all been twisted counterclockwise instead of what would be natural to a right-hander—and so were the murders all connected, and the various media-bequeathed epithets collapsed into a single name.

This is when Dark Mill South became sensationalized as the “Nomad,” a term dialed back from the throwaway “nomadic” the authorities used to explain his interstate peregrinations, but also stemming from the “Indian” silhouette the surviving camper from North Dakota insisted wasn’t her imagination—traditionally, before incursion by wave after wave of settlers, Plains Indians had been nomadic.

At this point, all indications were that this Nomad was responsible for the violent deaths of some thirty people.

Which is perhaps when Dark Mill South himself started counting.

The couple he killed in their car just outside Denver, Colorado, in June 2015 had “31” and “32” burned into their torsos with the cigarette lighter from the dashboard. They’d evidently been alive for this hours-long process, and it hadn’t quite killed them—a car lighter is no red-hot branding iron. What did kill them were the headrests of their seats, which had twin metal posts with adjustment notches in them. Dark Mill South lined those two metal posts up with this couple’s eyes and then pushed them in to the last notch. When found, the murdered couple had their seatbelts on, the car had been positioned to face north, and the radio was tuned to an oldies station high up on the AM band. One responding officer claimed that, while he’d once had a taste for what he called “Poodle Skirt Music,” he now preferred silence on patrol. The quieter the better.

The next three victims were in Elk Bend, Idaho—a 767 mile drive by the most direct route, which crosses Caribou-Targhee National Forest here in Fremont County. In Elk Bend, Dark Mill South took on the guise of Dugout Dick, the local legend, and stalked and eviscerated volunteer firemen with a railroad pickaxe. Finally, pushed to her limit and beyond, one of those firemen’s wives—Sally Chalumbert, Shoshone, technically a widow by this point—stalked this “Dugout Dick” back, and, in a final confrontation, bludgeoned him with a shovel. After Dark Mill South was down, though, Sally Chalumbert’s fury was still far from spent. Screaming, she continued beating him with her now-broken shovel, dislodging most of his front teeth, fracturing the bones of his face, and then using the blade of the shovel to neatly remove his right hand. The only reason she stopped there was that her husband’s brother tackled her away, trying to, as he said in his statement, “save her soul.”

He was too late.

The dark place Sally Chalumbert had to go to was a place she couldn’t come back from. Thus her continuing institutionalization.

Dark Mill South came back, though.

The good ones always do.

When he tried to swim the Salmon River and get away into his next killing spree, one of the remaining volunteer firemen rammed the county firetruck into a utility pole, dropping its transformer into the water. Before that power line shorted out, it killed every trout, muskrat, duck, and beaver in that portion of the Salmon, and apparently scalded a young moose as well.

Dark Mill South floated in to shore face down, his wrist and face seeping blood, and when he woke weeks later, he was strapped to a reinforced hospital bed, the charges against him accumulating fast, every federal agency wanting a piece of him, every state he’d passed through angling for extradition. The Nomad was a nomad no more.

In that one muttered and variously reconstructed interview he supposedly gave, recorded by a nurse who had been given questions she’d had to crib onto her inner forearm, Dark Mill South claimed that he wasn’t done yet. Thirty-five dead wasn’t thirty-eight, and that’s the number he was going for.

The media followed this number back to his home state of Minnesota, where thirty-eight Dakota men had been hanged in 1862—the largest mass execution in American history. Dark Mill South’s claim, then, the media surmised, was that he was merely taking lives to balance the scales of justice. Whether this had been his mission all along or if it were just something he picked up along the way was anybody’s guess. Either way, the effect was to permanently associate this 1862 atrocity with Dark Mill South’s seven-year, multi-state “rampage,” as it was now being called.

And so the Eastfork Strangler, the Ninety-Eye Slasher, the Bowman Butcher, the Rapid City Reaper, Dugout Dick, and the Nomad had their day in court, as Dark Mill South. Specifically, as he’d been arrested in Elk Bend, Idaho, Dark Mill South’s “day” was down in Boise. Since those three killings were the most recent, had the most evidence directly associated with him, even including cellphone footage of surprisingly good quality, it was felt that conviction was guaranteed in this case.

Dark Mill South was a media sensation by then, and nearly a celebrity—not just another serial killer after a half century of them, but the West’s favorite new boogeyman, a, according to one account in Montana, “latterday Jeremiah Johnson.” At an imposing six and a half feet tall, with shoulder length hair he never tied back but wore like a shroud, with a hook attached to the stump of his right wrist and a sly grimace permanently etched into the knotted scar tissue of his face, the public couldn’t look away. Fan fiction surfaced of him escaping his holding cell, making his way to the local lovers’ lane, and, with his hook hand, “giving precedent after the fact to all the urban legends, and making some new ones in the process.”

Because the so-called trials of the thirty-eight Dakota in 1862 had been as short as five minutes in some cases, Dark Mill’s day in court went for years, as every i needed careful dotting, every t the most patient crossing, and he had to get a new set of teeth installed besides. The Elk Bend Massacre, as it came to be known, had been July 3rd and 4th, 2015—a fateful day in the history of American violence, to be sure—but Dark Mill South’s much-negotiated plea deal wasn’t entered until mid–October 2019.

His claim was that he could show the officers of the court more of his north-facing dead if they were interested in that kind of thing, and had enough bodybags.

They were interested.

And of course nobody doubted that Dark Mill South could lead them to leathery body after leathery body in Wyoming, in Montana, and down through the Dakotas, across to Colorado. There could even be some in southern Idaho, on the way to Elk Bend, right? After all, there had been a sensational death along that path that had garnered national attention in the summer of 2015, and it very well could have been a murder, not just an animal attack. Better yet, if it could be established that Dark Mill South had passed that holy bodycount of “38” well before getting to Elk Bend, that would serve to mitigate the continuing outrage over all those Dakota men Abraham Lincoln had hanged in 1862, as they wouldn’t be people anymore, but simply an excuse a wily killer had used to rally public sympathy.

Social media dubbed this circuit The Reunion Tour—the killer reuniting with his victims.

The convoy of armored vehicles left Boise on Thursday, December 12th, 2019. Dark Mill South’s shackles supposedly had shackles, he had been doped to the gills besides, and the blacked-out SUV he was strapped into was one of four identical vehicles, each of the others mocked up to appear as if they too were carrying him. The fear was that the victims’ families might attempt an ambush, or—worse—that Dark Mill South’s ever-expanding fanbase might stage an escape.

There was air support, state troopers both led the way and rode drag, and local constabulary closed the roads ahead of this convoy when possible. And in what was surely a strategic slip, the speaker at the press conference laying all this out went “off-script” to whisper into his bouquet of microphones that there would at all times be an armed guard assigned to sit directly behind Dark Mill South, for “any eventualities,” which was of course wink-wink code for the last resort being a bullet to the back of the Nomad’s head, halting his murderous peregrinations once and for all.

If, indeed, a bullet would even be sufficient.

All of America poured a stiff drink and settled into their most comfortable chair to ride this out with the grim men and women assigned this task, but then the hour got late, the channel got changed for a quick look at the game, and… attention waned.

Which was just how the convoy of armored SUVs wanted it.

Better to travel in anonymity, well out of the camera’s eye. And, though they hadn’t counted on the weather helping them stay off the national radar, the weather was a boon in that regard all the same. When visibility is nil and the temperature’s in a nosedive, journalists can’t deliver progress reports to the world. The convoy ceased to be a blinking blue dot on a map over an anchorperson’s head. Instead, there were special reports interrupting the usual programming to warn viewers about this winter storm, this once-in-a-century whiteout.

The first of the interstates along the convoy’s route to shut down was I-80 across Wyoming, which was no surprise to anyone familiar with that stretch of highway. The convoy shrugged, went to their Plan B: the old stomping grounds of the Ninety-Eye Killer—Montana.

Retracing their route, they picked their way through Pocatello, then Blackfoot, intending to follow the I-15 north to Idaho Falls and then all the way up to Butte, ideally in a single push.

The blizzard rocking their SUVs didn’t agree: I-15 shut down as well, and wouldn’t open even for badges.

Now this convoy had no recourse but to either register at a hotel they hadn’t vetted or attempt a northern passage up Highway 20, which would spit them out just west of Yellowstone, right at the Montana state line.

When the call went out for a snowplow to clear the way for them out of Idaho Falls, three class 7 trucks showed up, each of them the size of a garbage or cement truck. The drivers let it be known that if that judge down in Boise needed someone to pull the switch on Dark Mill South’s electric chair or gas chamber or lethal injection, they could probably find an open slot in their schedule for that as well.

Or if, say, he were to accidentally fall out the side door of an SUV, then… well, it was slick, and snowplows are heavy, and that big blade’s gonna do what it’s gonna do, right?

There was much manly handshaking, many shoulders patted, and so began the slow grind up the mountain, the swirling gusts of snow revealing only greater blackness beyond and, every few miles, old billboards touting Proofrock, Idaho, as “The Silver Strike Heard ’Round the World!” and Proofrock’s Indian Lake as “The Best Kept Secret of the West.” By 2019, of course, these billboards had been defaced—a shark fin spray-painted onto the glittering surface of Indian Lake, along with the obligatory “Help! Shark!” dialogue balloon, the miner making that world-famous silver strike given overlarge eyes and a leering grin, since there was now the cartoon of a screaming woman painted in between his pickaxe and that seam of foil.

It’s probably safe to assume that Dark Mill South, seeing this graffiti through the storm, chuckled to himself with satisfaction. Just as the Marlboro Man would feel right at home walking into a forest of cigarettes, so would the Nomad recognize the country his convoy was broaching into. He was even, at this point, facing north.

As were his drivers, his guards, his handlers.

The individual flakes of snow crashed into the windshields and the wipers surely batted them away, smeared them in, fed them to the heat of the defrosters on full blast, but still the safety glass had to be icing over, making it tricky to stay locked on the taillights of the phalanx of snowplows leading the way, flinging great but silent curls of snow over the guardrail, out into open space.

Had air support been able to stay aloft in this storm, they would have had to hover so close over this crawling black line that their rotor wash would have only made visibility worse. But the two helicopters had retreated to the private airports hours behind, were handing the convoy off to Montana pilots, already waiting at their pads.

So, by 11 a.m., possibly 11:30 a.m., the convoy was out of the media eye, it had no air support, and it was being swallowed by the snow, by the blizzard, by the mountain. There was a team of snowplows carving a route, there was thermos after thermos of coffee for those drivers, but there was also Dark Mill South, perhaps already testing the limits of his shackles’ shackles—handcuffing a prisoner who only has a single hand is a tricky proposition, and some metabolisms burn through sedatives so fast you can almost see them steaming away.

It was like the West was calling him back. Like the land needed a cleansing agent to rove across the landscape, blood swelling up from each of his boot prints, his shadow so long and so deep that last cries whispered up from it.

Or so someone might say who believed in slashers and final girls, fate and justice.

But we’ll be getting to her later.

And everyone else as well.

First, though, this convoy lost in the whiteout, this Reunion Tour slouching toward a Bethlehem already swimming in blood.

Fifteen miles up Highway 20 is where accounts of that night begin to differ, Mr. Armitage, but where they converge again is a pier jutting out onto Indian Lake here in Proofrock, 8,000 feet up the mountain. In the offhand words of Deputy Sheriff Banner Tompkins—the sound bite that came to characterize this latest series of killings—“If we were looking anywhere for more bad shit to go down, we were looking out onto the lake, I guess. Not behind us.”

“Behind us” would be U.S. Highway 20.

Dark Mill South’s Reunion Tour began on December 12th, 2019, a Thursday.

Thirty-six hours and twenty bodies later, on Friday the 13th, it would be over.

As Martin Luther says on that poster by your chalkboard, “Blood alone moves the wheels of history.”

Our wheels are moving just fine, thank you.

Just, don’t look in the rearview mirror if you can help it.

SCREAM

This was so much easier when she was seventeen.

Jennifer Daniels looks to her left, out across the vast expanse of Indian Lake, then to the right, that long drop down and down and down, and she has to take a knee, tie her right boot tighter.

Her fingernails aren’t painted black, and her boots are the dress-ones her lawyer bought for her. The heels are conservative, there are no aggressive lugs on the soles, and the threads are the same dark brown color as the fake, purply-brown leather.

She stands up, is still kind of unsettled by all this open space, like it might swallow her, disappear her.

Her bangs blow into her eyes and she threads them away, and they don’t make that dry sound they always did. She’s still getting used to that, too: healthy hair. Long hair.

The jacket she’s wearing is from the sheriff’s office, because she didn’t have one. The jacket was balled in the backseat of the county Bronco. It’s Carhartt brown, with bright yellow conspicuity stripes down the arms and around the waist. It’s too big, fits her like a tunic. Her hands don’t reach the bottoms of the pockets. It makes her feel like a little girl, like she’s come out into the big bad cold with her dad and he’s wrapped her in his jacket because the wind doesn’t bother him, a lie that makes her even warmer.

When she buries her face in the lapel it smells like cigarettes.

“You can do this, girl,” she says to herself, and steps out onto the narrow concrete spine of the dam.

Why there’s still not any safety rails here, she can’t begin to imagine. This is walking a tightrope. If it were summer and she started to overbalance to her right, into that long silent fall, she could just fling herself the other way, fall back into the water, try to swim over to the rusty ladder there specifically because this is a drowning place. But this deep into winter, Indian Lake’s frozen. She would burst on its icy back, just be a splash of red for the wolves to come lick in secret. Scuffling out here across its wind-scoured surface, the safety cones all scattered, there were ice skate carvings back and forth like giant spiders dance there at night, and, farther out, there were wide tire tracks—the firetruck Proofrock always eases out, the second week of December, to show that the deep cold’s really and finally here.

Like anybody could ever doubt that. Still—and she’d never tell a soul this—it’s sort of good to be home. All through high school, her dream had been to blast off, escape down to Boise. She couldn’t get out of there fast enough, though.

Submitting her bare hands to the ten-degree chill, she holds her arms out to the side, places one foot in front of the other, no longer sure whether to watch where she’s walking or to fix her eyes on the control booth.

The silence out here is a pressure, almost. It makes her feel like her hearing’s been snatched from her.

Proofrock is so far down there it looks like a toy town, like a person in a Godzilla suit could step down through the drugstore, the bank, the post office, the motel. Not Dot’s, though, please. These last two days since Rex Allen ferried her back, slipped her the jacket and a couple of twenties, Dot’s coffee has been the only good thing.

In every place Jennifer Daniels puts her feet, there’s peg holes in the crusted snow, as if some daredevil of a clown’s been out here with a pogo stick.

She can’t let herself get distracted, though.

Halfway to the booth, she stops, is having a sort of panic attack.

Worse than anything, she wants to look behind her, so sure there’s going to be a trash bear standing there, leering at her.

She makes her lips into a wide oval and pants air in and out to try to calm herself. You can do this, she says inside, now. She has to. She at least owes him that.

On cue, then, the wind gusts from her right and she doesn’t know if she has to drop down to her hands and knees to keep from being blown off, but she does. Shaking and freezing and near throwing up, she crawls the rest of the way to the control booth, the heels of her hands and her knees burning with cold.

This is home, all right. Goddamnit.

At least there’s railing now around the little bulge of platform the booth occupies.

Jennifer stands, clamps onto it, and, just to be touching home base, keeps one frozen hand to the wall of the control booth.

Finally to the door, she bangs the side of her fist against it. Her whole forearm, really, all the way to the elbow. There’s still a divot in the metal at eye-height. It’s from the point of an axe, swung as hard as she could swing it.

It’s rusting now, and some joker with a marker’s scrawled 5 July 2015 beside it, and then, below that, in parentheses, jade.

Jennifer Daniels looks away from that.

One by one the door’s locks disengage, and then it pulls in, exhaling warmth around her.

Jennifer Daniels finally brings her eyes in from the lake, looks through the hair blowing across her face. She’s already blinking too fast.

“Well well well,” Hardy says, smiling one side of his mouth.

He’s leaning on a walker—the source of those peg holes out in the snow—and he’s gaunt, drawn, colorless. Losing feet of your intestines will do that to you.

Jennifer Daniels rushes forward all the same, buries her face in his chest.

Instead of closing the door, the former sheriff wraps the arm he can around her, pats her back while she sobs. He needs the other hand to stay on his walker, so they don’t both fall forward.

“This is my old jacket,” he says with wonder, down into the top of her head.

Jennifer Daniels tries to tell him she knows that, she remembers, she remembers everything, but she can’t exactly make words right now, can only press her face harder into his flannel shirt.

It smells like cigarettes too.

* * *

“Rex Allen could have chauffeured you up here the back way,” Hardy says over the dam version of coffee.

His second-best deputy is the sheriff now.

Torches were made to be passed, he figures.

Badges too.

Except, he only had two deputies, meaning Rex Allen was also the worst deputy.

But—not his headache anymore.

All he has to do is keep Indian Lake Indian Lake, the valley below them mostly dry.

Well, that and smoke cigarettes.

His skin is going yellow and drawn from being locked up here in this smoky cell, but it’s not like he ever planned to live forever, right?

He shouldn’t even really be alive now, he knows.

“He would have Banner do it,” Jade says—no: Jennifer. Jennifer Jennifer Jennifer. She’s already told him that’s who she is again. That “Jade” is dead. That she died that night in the water.

“‘Deputy Tompkins,’” Hardy says with a chuckle, adjusting the flow a smidge in the #2 tube. Not because it needs adjusting, but old men like to feel necessary.

“He always wanted to play college football,” Jennifer says, her eyes that kind of checked-out Hardy recognizes.

“Probably what he should be doing,” Hardy tells her.

Instead of grinning or even smiling, this new Jennifer stands, holding her coffee close for warmth, and studies the Terra Nova side of Indian Lake.

The trees are naked and black for about two acres into the national forest.

“You did that,” Hardy tells her, and when her eyes come back to him about that, he adds, “It would have all burned, I mean. You and Don Chambers, the valley owes the two of you. Maybe all of Idaho.”

He’s trying to build her back up, give her something to stand on, but she just shrugs it off, takes another drink, holding the mug with both hands. The sleeves on that jacket are long enough that she’s had to roll the cuffs back.

Hardy remembers another little girl who wore this same jacket, and has to look away.

“I’m living in my old house again,” Jennifer says, trying to make it into a sick joke. “My old bedroom, even.”

“Camp Blood,” Hardy says, commiserating.

He was down the mountain in surgery after surgery those first couple of years, but he was still getting reports. After that night in the water, all the murder tourists and horror junkies had come through Proofrock, and the Daniels house was one of the main stops. Then, when that finally died down with winter—snapshots for social media are fun, but not at twenty below—the high schoolers had jimmied the back door, made Jennifer’s old house into a party pad. Camp Winnemucca had always been that for them, but the lake was still spooky those first couple of years, the shore still haunted.

So: the Daniels house. And, because it kept them in out of the cold, kept them from starting bonfires that could get out of control, Rex Allen looked the other way. Which Hardy guesses is what sheriffing has come down to, these days.

Pretty soon some punk left “Camp Blood” spray-painted in red across the front of the house.

“It fits,” Jennifer says.

“You haven’t had hair like this since, what?” Hardy says, reaching forward to lift some of it up. “Fifth grade?”

“Sixth,” Jennifer says, blinking something away. She leans back, taking her new head of hair with her.

“Indian hair,” Hardy says, watching her eyes to see how she takes this.

He could have said her hair was like her dad’s, but he has a pretty good idea how that would go down. Anyway, she’s not saying anything about Trudy, so he’s not going to be bringing Tab Daniels up.

Neither is Ezekiel, he wants to add, except that last part, about her dad, wasn’t out loud, so adding anything to that would be awkward, to say the least. Spending all his time up here alone, it’s easy to lose track of what’s in his head, what’s not.

Which he guesses is the idea.

Jennifer doesn’t answer about her Indian hair, just chucks her chin out the bulletproof glass, says, “Everybody down there has PTSD, you know?”

Now it’s Hardy’s turn to duck the question. But yeah, he does know. When he first came back, was still in the wheelchair, it had given him a better angle on everybody in town. If you watch their faces, their eyes, then it’s business as usual, they’ve already put that night behind them, are just thinking about the future, or the moment, not that night in the water. But don’t fall for those poker faces. Instead, watch them sitting at the outdoor tables at Dot’s. Watch them leaning against that chipped blue pole at Lonnie’s while their cars gulp gas in. Watch them sitting on Melanie’s bench for the last little bit of the sunset.

They’ll make it three minutes, five minutes, their book distracting them, this phone call taking all their attention, this bite of omelette so perfect. But then, when their mental discipline slips—you can see it happen: a shoulder will twitch, a hand will clench into a sudden fist. A chest will fill with air as if the lake is washing over them all over again.

Better to sit up here on this impossible cliff of water and smoke a thousand cigarettes.

Speaking of—

Hardy thumbs his pack up from his shirt pocket, packs them, and shakes one up for Jennifer.

She shakes her head no, thanks.

“Good,” he says, taking that lead smoke himself. “You’re a stronger person than I am.”

“If I start, I won’t be able to stop,” she explains. “And I can’t afford them, right?”

“I can make a call or two,” Hardy tells her, digging for a match. “I might have lost three feet of my gut, but I still throw some weight around down there, can get you on the clock somewhere.”

Jennifer closes her eyes, nods thank you, her eyes filling with either gratitude or regret, it’s hard to tell. Either way, Hardy gives her her privacy, falls into his coughing routine, the one that makes him feel hollow inside.

“You good?” Jennifer asks, real concern in her voice, but a concern tinged with something a lot like anger, like this damnable cough is something she can fight—that she will fight.

She’s still in there, all right. Somewhere. Under everything that’s happened to her, everything that’s been piled onto her. Everything she’s still carrying, or trying to.

She’s only twenty-two years old, Hardy reminds himself.

The world is shit, to not have treated her better.

She should be on a full-ride scholarship at some school far away. All she should be worried about is a test, a date, a party.

Instead, her only friend is an old man dying in a concrete box at the top of the world, and her only memories are stained with blood.

So as not to be a complete insensitive, Hardy guides his cigarette from his lips back into the pack, sure to turn it around upside down so it won’t lose its place in line. It’s stupid being superstitious like that, he knows, but if you don’t have private little rituals, the days can lose their meaning real fast.

“How long you got up here?” he says to her.

“Why?”

“You’ll see,” he says, nodding down to the lake.

It’s three in the afternoon already, and dark at four, and she probably isn’t watching the barometer—kids—doesn’t know that that storm that’s stalled out down the mountain isn’t stalled anymore. With dusk the temperature’s going to plunge so fast it’ll punch the bottom out of the thermometer.

Hardy palms his radio, holds his finger up for Jennifer to be quiet, and squelches Meg in.

“Sheriff,” she says, and Hardy can just about see her back straightening to prim and proper now that the real boss is in the room.

“Gonna need a car up here in about forty-five minutes,” he says.

“You’re already on the schedule for six,” she reminds him in her clipped way, but that just means she’s flustered, he knows. The distinct sound of shuffling papers comes through her mic.

Because driving’s complicated for him, and because he is who he is, the sheriff’s office sends someone the back way to ferry him home each night. Meaning he only ever sees Proofrock at night, now. It’s becoming a shadow town for him, which, taking into account all the ghosts, is about right.

“You make it happen, Meggie?” Hardy asks. “Don’t want to get caught up here when it starts in blowing good.”

“Already doing it,” Meg says.

“And don’t send that kid,” Hardy adds with mock seriousness, holding Jennifer’s eyes about that.

She shakes her eyes like this is all so stupid, and she’s not wrong.

Hardy grandly clicks off, reseats the mic. It takes two tries to get it to stay.

“You don’t have to do that,” Jennifer says about him calling them a ride.

“I’m not sending you out there after dark,” he tells her, pointing through the window out to the lake, the night, all of it. “You step onto that soft spot, you’re gone, goodbye, world.”

“I saw the cones, I know where it is.”

“The cones that are blown to hell and gone?”

“I can leave now, it won’t be—”

“You’ll want to see this.”

“There’s something in this valley that can still surprise me?” she asks.

“Glad you made the trip,” Hardy tells her, lifting his mug in appreciation.

“Sorry I was such a… such a handful, back when,” she tells him, like maybe that’s the reason she made the long walk all the way up here.

“Was always interesting,” Hardy says back. “That time you wore those knife hands to school?”

“They weren’t real.”

“You still believe in all that?”

“In slashers? That was a long time ago. I was a—a different person, I don’t know.”

Hardy shrugs sure, and Jennifer shrugs back, says about all the space out the window, “You ever think about him?”

Hardy looks out into the grey sky with her.

“Bear,” he adds, obviously.

Mr. Grady “Bear” “Sherlock” Holmes, because one name would have never been enough for him.

“I do,” Jennifer says, all the muscles around her mouth tight. “I—it’s stupid.”

“So am I,” Hardy says with his stupidest grin.

Jennifer looks down into her mug, says, “I was… my lawyer said it would look good for the court if I took a lot of correspondence courses from the community college. Doing all that writing papers, reading history books, sometimes I would forget he was—he was—”

She leans her head back, working her throat to keep from crying again.

“I would forget what happened,” she goes on. “I would think how surprised he was going to be when I came back, had all that course credit.”

Now it’s Hardy who has to press his lips together, study the window glass.

“You did always have it in you,” he finally says. “I’m not surprised at all, Ja—Jennifer.”

She flicks her eyes up about her old name almost slipping in here, but doesn’t call him on it.

“Listen,” she says, setting her mug down, “I should—”

“Right on schedule,” Hardy says, leaning forward.

Jennifer tracks where he’s directing.

It’s the ruins of Terra Nova.

“I think they bed down over in Sheep’s Head,” he says about the small herd of elk picking their way down through the burnt houses and charred trees.

“But the lake’s frozen,” Jennifer says.

“They’re not drinking,” Hardy tells her. “It’s—that’s where the construction crew’s bank of port-a-johns were, remember?”

Jennifer narrows her eyes, dialing back, it looks like.

“Two blue ones and that wide grey one,” she says, nodding.

“After the… after what happened,” Hardy says, “nobody came and picked them up for that first year. But they were just plastic, couldn’t make it through winter. They cracked up, spilled. It’s like… you wouldn’t know, growing up in town. But the grass over a septic tank is always the greenest, the best. It’s the same there, and for the same natural reason. The grass was lush right there. Last summer, this little herd couldn’t stay away.”

“But it’s all gone now,” Jennifer says.

“Elk are hopeful, and they have good memories,” Hardy says, and directs her down there again, to the big bull pawing at the snow, to see if the good days are here again. And to… to the other one, stepping lightly down from the trees, fully aware of how obvious he is. How conspicuous.

“Oh,” Jennifer says, steepling both her hands over her mouth and drawing her breath in. “It’s—he’s white.”

“Snake Indians would have called him a spirit elk,” Hardy says. “And he doesn’t show himself for just anybody.”

“It’s the—it’s the storm,” Jennifer says.

“It’s you,” Hardy corrects, gently, and the way he can tell that Jennifer feels this is how the muscles around her mouth tighten her lips into a line. Like she’s trying to keep them from trembling.

Her chin is a prune, though.

Hardy gives her her privacy, doesn’t intrude on this moment anymore, and four or five minutes later, the elk pick their way back up the slope, fade into the trees, the white elk the last to leave.

“Thank you,” Jennifer says.

Hardy nods once.

Skirls of snow are swirling across the ice of Indian Lake, meaning things are about to pick up again.

Hardy bundles up, offers his scarf to Jennifer, and then he’s reaching his walker out along the dam’s icy backbone and pulling himself to it, the girl’s hands holding tight to the back of his jacket, and he kind of suspects that, with her letting him lead her like that, and take the brunt of the wind, he could maybe walk across all of Idaho.

* * *

Deputy Sheriff Banner Tompkins is drumming fast on the steering wheel of the snowcat when the old man materializes out of the storm, his edges blurry like he’s an oil painting leaking sideways.

Banner slows that drumbeat to more like sixty per minute, leans forward.

The ponderous single wiper on the cat is good enough to keep it between the sidewalks in town, but, facing the wind like this, the slush has been trying to freeze on the windshield. Banner wipes at the fog on his side of that glass but the forearm of his jacket sops up exactly nothing.

Step by walker-assisted step, then, the oil painting gaining resolution, Hardy goes from six legs to… eight? Him, his aluminum walker with the tennis ball feet, and—

He isn’t alone? What the hell, old man? Taking hitchhikers here, at the top of the world?