Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Strelbytskyy Multimedia Publishing

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

Nellie Bly (born Elizabeth Jane Cochran) was an American journalist, writer, and entrepreneur. She made a name for herself and pioneered the field of investigative journalism by writing an undercover expose on a woman's lunatic asylum. Her colorful and hands-on reporting style earned her the nickname of "girl stunt reporter." In 1889 she pitched the idea of a trip around the world to her editor. In the spirit of Jules Verne's character Phileas Fogg, Bly proposed she could circle the globe in less than 80 days. On November 14, 1889, Nellie achieved her goal, having circled the globe in exactly 72 days, 6 hours, and 10 minutes. During her trip, Bly visited England, and France (where she met with Jules Verne), as well as Italy, the Suez Canal, Ceylon, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Japan. Contents: Around the World in Seventy-Two Days Ten Days in a Mad-House; or, Nellie Bly's Experience on Blackwell's Island Six Months in Mexico

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 850

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE COLLECTED WORKS OF NELLIE BLY:

Ten Days in a Mad-House, Around the World in Seventy-Two Days and More

(illustrated)

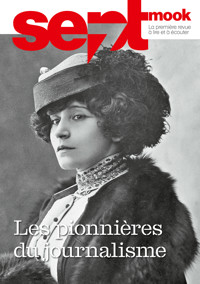

Nellie Bly (born Elizabeth Jane Cochran) was an American journalist, writer, and entrepreneur. She made a name for herself and pioneered the field of investigative journalism by writing an undercover expose on a woman’s lunatic asylum. Her colorful and hands-on reporting style earned her the nickname of “girl stunt reporter.”

In 1889 she pitched the idea of a trip around the world to her editor. In the spirit of Jules Verne’s character Phileas Fogg, Bly proposed she could circle the globe in less than 80 days. On November 14, 1889, Nellie achieved her goal, having circled the globe in exactly 72 days, 6 hours, and 10 minutes. During her trip, Bly visited England, and France (where she met with Jules Verne), as well as Italy, the Suez Canal, Ceylon, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Japan.

Around the World in Seventy-Two Days

Ten Days in a Mad-House; or, Nellie Bly's Experience on Blackwell's Island.

Six Months in Mexico

AROUND THE WORLD IN SEVENTY-TWO DAYS

CHAPTER I.

A PROPOSAL TO GIRDLE THE EARTH.

WHAT gave me the idea?

It is sometimes difficult to tell exactly what gives birth to an idea. Ideas are the chief stock in trade of newspaper writers and generally they are the scarcest stock in market, but they do come occasionally,

This idea came to me one Sunday. I had spent a greater part of the day and half the night vainly trying to fasten on some idea for a newspaper article. It was my custom to think up ideas on Sunday and lay them before my editor for his approval or disapproval on Monday. But ideas did not come that day and three o'clock in the morning found me weary and with an aching head tossing about in my bed. At last tired and provoked at my slowness in finding a subject, something for the week's work, I thought fretfully:

"I wish I was at the other end of the earth!"

"And why not?" the thought came: "I need a vacation; why not take a trip around the world?"

It is easy to see how one thought followed another. The idea of a trip around the world pleased me and I added: "If I could do it as quickly as Phileas Fogg did, I should go."

Then I wondered if it were possible to do the trip eighty days and afterwards I went easily off to sleep with the determination to know before I saw my bed again if Phileas Fogg's record could be broken.

I went to a steamship company's office that day and made a selection of time tables. Anxiously I sat down and went over them and if I had found the elixir of life I should not have felt better than I did when I conceived a hope that a tour of the world might be made in even less than eighty days.

I approached my editor rather timidly on the subject. I was afraid that he would think the idea too wild and visionary.

"Have you any ideas?" he asked, as I sat down by his desk.

"One," I answered quietly.

He sat toying with his pens, waiting for me to continue, so I blurted out:

"I want to go around the world!"

"Well?" he said, inquiringly looking up with a faint smile in his kind eyes.

"I want to go around in eighty days or less. I think I can beat Phileas Fogg's record. May I try it?"

To my dismay he told me that in the office they had thought of this same idea before and the intention was to send a man. However he offered me the consolation that he would favor my going, and then we went to talk with the business manager about it.

"It is impossible for you to do it," was the terrible verdict. "In the first place you are a woman and would need a protector, and even if it were possible for you to travel alone you would need to carry so much baggage that it would detain you in making rapid changes. Besides you speak nothing but English, so there is no use talking about it; no one but a man can do this."

"Very well," I said angrily, "Start the man, and I'll start the same day for some other newspaper and beat him."

"I believe you would," he said slowly. I would not say that this had any influence on their decision, but I do know that before we parted I was made happy by the promise that if any one was commissioned to make the trip, I should be that one.

After I had made my arrangements to go, other important projects for gathering news came up, and this rather visionary idea was put aside for a while.

One cold, wet evening, a year after this discussion, I received a little note asking me to come to the office at once. A summons, late in the afternoon, was such an unusual thing to me that I was to be excused if I spent all my time on the way to the office wondering what I was to be scolded for.

I went in and sat down beside the editor waiting for him to speak. He looked up from the paper on which he was writing and asked quietly: "Can you start around the world day after tomorrow?"

"I can start this minute," I answered, quickly trying to stop the rapid beating of my heart.

"We did think of starting you on the City of Paris tomorrow morning, so as to give you ample time to catch the mail train out of London. There is a chance if the Augusta Victoria, which sails the morning afterwards, has rough weather of your failing to connect with the mail train."

"I will take my chances on the Augusta Victoria, and save one extra day," I said.

The next morning I went to Ghormley, the fashionable dressmaker, to order a dress. It was after eleven o'clock when I got there and it took but very few moments to tell him what I wanted.

I always have a comfortable feeling that nothing is impossible if one applies a certain amount of energy in the right direction. When I want things done, which is always at the last moment, and I am met with such an answer: "It's too late. I hardly think it can be done;" I simply say:

"Nonsense! If you want to do it, you can do it. The question is, do you want to do it?"

I have never met the man or woman yet who was not aroused by that answer into doing their very best.

If we want good work from others or wish to accomplish anything ourselves, it will never do to harbor a doubt as to the result of an enterprise.

So, when I went to Ghormley's, I said to him: "I want a dress by this evening."

"Very well," he answered as unconcernedly as if it were an everyday thing for a young woman to order a gown on a few hours' notice.

"I want a dress that will stand constant wear for three months," I added, and then let the responsibility rest on him.

Bringing out several different materials he threw them in artistic folds over a small table, studying the effect in a pier glass before which he stood.

He did not become nervous or hurried. All the time that he was trying the different effects of the materials, he kept up a lively and half humorous conversation. In a few moments he had selected a plain blue broadcloth and a quiet plaid camel's-hair as the most durable and suitable combination for a traveling gown.

Before I left, probably one o'clock, I had my first fitting. When I returned at five o'clock for a second fitting, the dress was finished. I considered this promptness and speed a good omen and quite in keeping with the project.

After leaving Ghormley's I went to a shop and ordered an ulster. Then going to another dressmaker's, I ordered a lighter dress to carry with me to be worn in the land where I would find summer.

I bought one hand-bag with the determination to confine my baggage to its limit.

That night there was nothing to do but write to my few friends a line of farewell and to pack the hand-bag.

Packing that bag was the most difficult undertaking of my life; there was so much to go into such little space.

I got everything in at last except the extra dress. Then the question resolved itself into this: I must either add a parcel to my baggage or go around the world in and with one dress. I always hated parcels so I sacrificed the dress, but I brought out a last summer's silk bodice and after considerable squeezing managed to crush it into the hand-bag.

I think that I went away one of the most superstitious of girls. My editor had told me the day before the trip had been decided upon of an inauspicious dream he had had. It seemed that I came to him and told him I was going to run a race. Doubting my ability as a runner, he thought he turned his back so that he should not witness the race. He heard the band play, as it does on such occasions, and heard the applause that greeted the finish. Then I came to him with my eyes filled with tears and said: "I have lost the race."

"I can translate that dream," I said, when he finished; "I will start to secure some news and some one else will beat me."

When I was told the next day that I was to go around the world I felt a prophetic awe steal over me. I feared that Time would win the race and that I should not make the tour in eighty days or less.

Nor was my health good when I was told to go around the world in the shortest time possible at that season of the year. For almost a year I had been a daily sufferer from headache, and only the week previous I had consulted a number of eminent physicians fearing that my health was becoming impaired by too constant application to work. I had been doing newspaper work for almost three years, during which time I had not enjoyed one day's vacation. It is not surprising then that I looked on this trip as a most delightful and much needed rest.

The evening before I started I went to the office and was given £200 in English gold and Bank of England notes. The gold I carried in my pocket. The Bank of England notes were placed in a chamois-skin bag which I tied around my neck. Besides this I took some American gold and paper money to use at different ports as a test to see if American money was known outside of America.

Down in the bottom of my hand-bag was a special passport, number 247, signed by James G. Blaine, Secretary of State. Someone suggested that a revolver would be a good companion piece for the passport, but I had such a strong belief in the world's greeting me as I greeted it, that I refused to arm myself. I knew if my conduct was proper I should always find men ready to protect me, let them be Americans, English, French, German or anything else.

It is quite possible to buy tickets in New York for the entire trip, but I thought that I might be compelled to change my route at almost any point, so the only transportation I had provided on leaving New York was my ticket to London.

When I went to the office to say good-bye, I found that no itinerary had been made of my contemplated trip and there was some doubt as to whether the mail train which I expected to take to Brindisi, left London every Friday night. Nor did we know whether the week of my expected arrival in London was the one in which it connected with the ship for India or the ship for China. In fact when I arrived at Brindisi and found the ship was bound for Australia, I was the most surprised girl in the world.

I followed a man who had been sent to a steamship company's office to try to make out a schedule and help them arrange one as best they could on this side of the water. How near it came to being correct can be seen later on.

I have been asked very often since my return how many changes of clothing I took in my solitary hand-bag. Some have thought I took but one; others think I carried silk which occupies but little space, and others have asked if I did not buy what I needed at the different ports.

One never knows the capacity of an ordinary hand-satchel until dire necessity compels the exercise of all one's ingenuity to reduce every thing to the smallest possible compass. In mine I was able to pack two traveling caps, three veils, a pair of slippers, a complete outfit of toilet articles, ink-stand, pens, pencils, and copy-paper, pins, needles and thread, a dressing gown, a tennis blazer, a small flask and a drinking cup, several complete changes of underwear, a liberal supply of handkerchiefs and fresh ruchings and most bulky and uncompromising of all, a jar of cold cream to keep my face from chapping in the varied climates I should encounter.

That jar of cold cream was the bane of my existence. It seemed to take up more room than everything else in the bag and was always getting into just the place that would keep me from closing the satchel. Over my arm I carried a silk waterproof, the only provision I made against rainy weather. After-experience showed me that I had taken too much rather than too little baggage. At every port where I stopped at I could have bought anything from a ready-made dress down, except possibly at Aden, and as I did not visit the shops there I cannot speak from knowledge.

The possibilities of having any laundry work done during my rapid progress was one which had troubled me a good deal before starting. I had equipped myself on the theory that only once or twice in my journey would I be able to secure the services of a laundress. I knew that on the railways it would be impossible, but the longest railroad travel was the two days spent between London and Brindisi, and the four days between San Francisco and New York. On the Atlantic steamers they do no washing. On the Peninsular and Oriental steamers-which everyone calls the P. amp; O. boats-between Brindisi and China, the quartermaster turns out each day a wash that would astonish the largest laundry in America. Even if no laundry work was done on the ships, there are at all of the ports where they stop plenty of experts waiting to show what Orientals can do in the washing line. Six hours is ample time for them to perform their labors and when they make a promise to have work done in a certain time, they are prompt to the minute. Probably it is because they have no use for clothes themselves, but appreciate at its full value the money they are to receive for their labor. Their charges, compared with laundry prices in New York, are wonderfully low.

So much for my preparations. It will be seen that if one is traveling simply for the sake of traveling and not for the purpose of impressing one's fellow passengers, the problem of baggage becomes a very simple one. On one occasion-in Hong Kong, where I was asked to an official dinner-I regretted not having an evening dress with me, but the loss of that dinner was a very small matter when compared with the responsibilities and worries I escaped by not having a lot of trunks and boxes to look after.

CHAPTER II.

THE START.

ON Thursday, November 14, 1889, at 9.40.30 o'clock, I started on my tour around the world.

Those who think that night is the best part of the day and that morning was made for sleep, know how uncomfortable they feel when for some reason they have to get up with-well, with the milkman.

I turned over several times before I decided to quit my bed. I wondered sleepily why a bed feels so much more luxurious, and a stolen nap that threatens the loss of a train is so much more sweet, than those hours of sleep that are free from duty's call. I half promised myself that on my return I would pretend sometime that it was urgent that I should get up so I could taste the pleasure of a stolen nap without actually losing anything by it. I dozed off very sweetly over these thoughts to wake with a start, wondering anxiously if there was still time to catch the ship.

Of course I wanted to go, but I thought lazily that if some of these good people who spend so much time in trying to invent flying machines would only devote a little of the same energy towards promoting a system by which boats and trains would always make their start at noon or afterwards, they would be of greater assistance to suffering humanity.

I endeavored to take some breakfast, but the hour was too early to make food endurable. The last moment at home came. There was a hasty kiss for the dear ones, and a blind rush downstairs trying to overcome the hard lump in my throat that threatened to make me regret the journey that lay before me.

"Don't worry," I said encouragingly, as I was unable to speak that dreadful word, goodbye; "only think of me as having a vacation and the most enjoyable time in my life."

Then to encourage myself I thought, as I was on my way to the ship: "It's only a matter of 28,000 miles, and seventy-five days and four hours, until I shall be back again."

A few friends who told of my hurried departure, were there to say good-bye. The morning was bright and beautiful, and everything seemed very pleasant while the boat was still; but when they were warned to go ashore, I began to realize what it meant for me.

"Keep up your courage," they said to me while they gave my hand the farewell clasp. I saw the moisture in their eyes and I tried to smile so that their last recollection of me would be one that would cheer them.

But when the whistle blew and they were on the pier, and I was on the Augusta Victoria, which was slowly but surely moving away from all I knew, taking me to strange lands and strange people, I felt lost. My head felt dizzy and my heart felt as if it would burst. Only seventy-five days! Yes, but it seemed an age and the world lost its roundness and seemed a long distance with no end, and-well, I never turn back.

I looked as long as I could at the people on the pier. I did not feel as happy as I have at other times in life. I had a sentimental longing to take farewell of everything.

"I am off," I thought sadly, "and shall I ever get back?"

Intense heat, bitter cold, terrible storms, shipwrecks, fevers, all such agreeable topics had been drummed into me until I felt much as I imagine one would feel if shut in a cave of midnight darkness and told that all sorts of horrors were waiting to gobble one up.

The morning was beautiful and the bay never looked lovelier. The ship glided out smoothly and quietly, and the people on deck looked for their chairs and rugs and got into comfortable positions, as if determined to enjoy themselves while they could, for they did not know what moment someone would be enjoying themselves at their expense.

When the pilot went off everybody rushed to the side of the ship to see him go down the little rope ladder. I watched him closely, but he climbed down and into the row boat, that was waiting to carry him to the pilot boat, without giving one glance back to us. It was an old story to him, but I could not help wondering if the ship should go down, whether there would not be some word or glance he would wish he had given.

"You have now started on your trip," someone said to me. "As soon as the pilot goes off and the captain assumes command, then, and only then our voyage begins, so now you are really started on your tour around the world."

Something in his words turned my thoughts to that demon of the sea-sea-sickness.

Never having taken a sea voyage before, I could expect nothing else than a lively tussle with the disease of the wave.

"Do you get sea-sick?" I was asked in an interested, friendly way. That was enough; I flew to the railing.

Sick? I looked blindly down, caring little what the wild waves were saying, and gave vent to my feelings.

People are always unfeeling about sea-sickness. When I wiped the tears from my eyes and turned around, I saw smiles on the face of every passenger. I have noticed that they are always on the same side of the ship when one is taken suddenly, overcome, as it were, with one's own emotions.

The smiles did not bother me, but one man said sneeringly:

"And she's going around the world!"

I too joined in the laugh that followed. Silently I marveled at my boldness to attempt such a feat wholly unused, as I was, to sea-voyages. Still I did not entertain one doubt as to the result.

Of course I went to luncheon. Everybody did, and almost everybody left very hurriedly. I joined them, or, I don't know, probably I made the start. Anyway I never saw as many in the dining room at any one time during the rest of the voyage.

When dinner was served I went in very bravely and took my place on the Captain's left. I had a very strong determination to resist my impulses, but yet, in the bottom of my heart was a little faint feeling that I had found something even stronger than my will power.

Dinner began very pleasantly. The waiters moved about noiselessly, the band played an overture, Captain Albers, handsome and genial, took his place at the head, and the passengers who were seated at his table began dinner with a relish equaled only by enthusiastic wheelmen when roads are fine. I was the only one at the Captain's table who might be called an amateur sailor. I was bitterly conscious of this fact. So were the others.

I might as well confess it, while soup was being served, I was lost in painful thoughts and filled with a sickening fear. I felt that everything was just as pleasant as an unexpected gift on Christmas, and I endeavored to listen to the enthusiastic remarks about the music made by my companions, but my thoughts were on a topic that would not bear discussion.

I felt cold, I felt warm; I felt that I should not get hungry if I did not see food for seven days; in fact, I had a great, longing desire not to see it, nor to smell it, nor to eat of it, until I could reach land or a better understanding with myself.

Fish was served, and Captain Albers was in the midst of a good story when I felt I had more than I could endure.

"Excuse me," I whispered faintly, and then rushed, madly, blindly out. I was assisted to a secluded spot where a little reflection and a little unbridling of pent up emotion restored me to such a courageous state that I determined to take the Captain's advice and return to my unfinished dinner.

"The only way to conquer sea-sickness is by forcing one's self to eat," the Captain said, and I thought the remedy harmless enough to test.

They congratulated me on my return. I had a shamed feeling that I was going to misbehave again, but I tried to hide the fact from them. It came soon, and I disappeared at the same rate of speed as before.

Once again I returned. This time my nerves felt a little unsteady and my belief in my determination was weakening, Hardly had I seated myself when I caught an amused gleam of a steward's eye, which made me bury my face in my handkerchief and choke before I reached the limits of the dining hall.

The bravos with which they kindly greeted my third return to the table almost threatened to make me lose my bearings again. I was glad to know that dinner was just finished and I had the boldness to say that it was very good!

I went to bed shortly afterwards. No one had made any friends yet, so I concluded sleep would be more enjoyable than sitting in the music hall looking at other passengers engaged in the same first-day-at-sea occupation.

I went to bed shortly after seven o'clock. I had a dim recollection afterwards of waking up enough to drink some tea, but beyond this and the remembrance of some dreadful dreams, I knew nothing until I heard an honest, jolly voice at the door calling to me.

Opening my eyes I found the stewardess and a lady passenger in my cabin and saw the Captain standing at the door.

"We were afraid that you were dead," the Captain said when he saw that I was awake.

"I always sleep late in the morning," I said apologetically.

"In the morning!" the Captain exclaimed, with a laugh, which was echoed by the others, "It is half-past four in the evening!"

"But never mind," he added consolingly, "as long as you slept well it will do you good. Now get up and see if you can't eat a big dinner."

I did. I went through every course at dinner without flinching, and stranger still, I slept that night as well as people are commonly supposed to sleep after long exercise in the open air.

The weather was very bad, and the sea was rough, but I enjoyed it. My sea-sickness had disappeared, but I had a morbid, haunting idea, that although it was gone, it would come again, still I managed to make myself comfortable.

Almost all of the passengers avoided the dining-room, took their meals on deck and maintained reclining positions with a persistency that grew monotonous. One bright, clever, American-born girl was traveling alone to Germany, to her parents. She entered heartily into anything that was conducive to pleasure. She was a girl who talked a great deal and she always said something. I have rarely, if ever, met her equal. In German as well as English, she could ably discuss anything from fashions to politics. Her father and her uncle are men well-known in public affairs, and by this girl's conversation it was easy to see that she was a father's favorite child; she was so broad and brilliant and womanly. There was not one man on board who knew more about politics, art, literature or music, than this girl with Marguerite hair, and yet there was not one of us more ready and willing to take a race on deck than was she.

I think it is only natural for travelers to take an innocent pleasure in studying the peculiarities of their fellow companions. We were not out many days until everybody that was able to be about had added a little to their knowledge of those that were not. I will not say that the knowledge acquired in that way is of any benefit, nor would I try to say that those passengers who mingled together did not find one another as interesting and as fit subjects for comment. Nevertheless it was harmless and it afforded us some amusement.

I remember when I was told that we had among the passengers one man who counted his pulse after every meal, and they were hearty meals, too, for he was free from the disease of the wave, that I waited quite eagerly to have him pointed out, so that I might watch him. If it had been my pulse, instead of his own, that he watched so carefully, I could not have been more interested thereafter. Every day I became more anxious and concerned until I could hardly refrain from asking him if his pulse decreased before meals and increased afterwards, or if it was the same in the evening as it was in the morning.

I almost forgot my interest in this one man, when my attention was called to another, who counted the number of steps he took every day. This one in turn became less interesting when I found that one of the women, who had been a great sufferer from sea-sickness, had not undressed since she left her home in New York.

"I am sure we are all going down," she said one day in a burst of confidence, "and I am determined to go down dressed!"

I was not surprised after this that she was so dreadfully sea-sick.

One family who were removing from New York to Paris, had with them a little silver skye terrier, which bore the rather odd name of "Home, Sweet Home." Fortunately for the dog, as well as for those who were compelled to speak to him, they had shortened the name into "Homie."

"Homie's" passage was paid, but according to the rules of the ship, "Homie" was confined to the care of the butcher, much to the disgust of his master and mistress. "Homie" had not been accustomed to such harsh measures before, and the only streaks of happiness that came into his life were when permission was obtained for him to come on deck. Permission was granted with a proviso that if "Homie" barked he was to be taken instantly below. I fear that many hours of "Homie's" imprisonment might be laid at our door, for he knew how to dig most frantically when anyone said, "Rats," and when he did dig, he usually punctuated his attempt with short, crisp barks. With dismay we daily noted "Homie's" decrease in flesh. We marveled at his losing weight while confined in the butcher's quarters, and at last put it down to sea-sickness, which he, like some of the passengers, confined to the secrecy of his cabin. Towards the end of the voyage, when we were all served with sausage and Hamburger steak, there would be many whispered inquiries as to whether "Homie" had been seen that day. So anxious became those whispers that sometimes I thought they were rather tinged with a personal concern that was not wholly friendship for the wee dog.

When everything else grew tiresome, Captain Albers would always invent something to amuse us. He made a practice every evening after dinner, of putting the same number of lines on a card as there were gentlemen at the table. One of these lines he would mark and then partly folding the card over so as to prevent the marked line from being seen. would pass it around for the men to take their choice.

After all had marked, the card was passed to the Captain, and we would wait breathlessly for the verdict. The gentleman whose name had been marked paid for the cigars or cordials for the others.

Many were the discussions about the erroneous impression entertained by most foreigners about Americans and America. Some one remarked that the majority of people in foreign lands were not able to tell where the United States is.

"There are plenty of people who think the United States is one little island, with a few houses on it," Captain Albers said. "Once there was delivered at my house, near the wharf, in Hoboken, a letter from Germany, addressed to,

'CAPTAIN ALBERS,

FIRST HOUSE IN AMERICA.'"

"I got one from Germany once," said the most bashful man at the table, his face flushing at the sound of his own voice, "addressed to,

'HOBOKEN, OPPOSITE THE UNITED STATES.'"

While at luncheon on the 21st of November, some one called out that we were in sight of land. The way everyone left the table and rushed on deck was surely not surpassed by the companions of Columbus when they discovered America. I can not give any good reason for it, but I know that I looked at the first point of bleak land with more interest than I would have bestowed on the most beautiful bit of scenery in the world.

We had not been long in sight of land until the decks began to fill with dazed-looking, wan-faced people. It was just as if we had taken on new passengers. We could not realize that they were from New York and had been enjoying (?) a season of seclusion since leaving that port.

Dinner that evening was a very pleasant affair. Extra courses had been prepared in honor of those that were leaving at Southampton. I had not known one of the passengers when I left New York seven days before, but I realized, now that I was so soon to separate from them, that I regretted the parting very much.

Had I been traveling with a companion I should not have felt this so keenly, for naturally then I would have had less time to cultivate the acquaintance of my fellow passengers.

They were all so kind to me that I should have been the most ungrateful of women had I not felt that I was leaving friends behind. Captain Albers had served many years as commander of a ship in Eastern seas, and he cautioned me as to the manner in which I should take care of my health. As the time grew shorter for my stay on the Augusta Victoria, some teased me gently as to the outcome of my attempt to beat the record made by a hero of fiction, and I found myself forcing a false gaiety that helped to hide my real fears.

The passengers on the Augusta Victoria all stayed up to see us off. We sat on deck talking or nervously walking about until half-past two in the morning. Then some one said the tugboat had come alongside, and we all rushed over to see it. After it was made secure we went down to the lower deck to see who would come on and to get some news from land.

One man was very much concerned about my making the trip to London alone. He thought as it was so late, or rather so early, that the London correspondent, who was to have met me, would not put in an appearance.

"I shall most certainly leave the ship here and see you safely to London, if no one comes to meet you," he protested, despite my assurances that I felt perfectly able to get along safely without an escort.

More for his sake than my own, I watched the men come on board, and tried to pick out the one that had been sent to meet me. Several of them were passing us in a line just as a gentleman made some remark about my trip around the world. A tall young man overheard the remark, and turning at the foot of the stairs, looked down at me with a hesitating smile.

"Nellie Bly?" he asked inquiringly.

"Yes," I replied, holding out my hand, which he gave a cordial grasp, meanwhile asking if I had enjoyed my trip, and if my baggage was ready to be transferred.

The man who had been so fearful of my traveling to London alone, took occasion to draw the correspondent into conversation. Afterwards he came to me and said with the most satisfied look upon his face:

"He is all right. If he had not been so, I should have gone to London with you anyway. I can rest satisfied now for he will take care of you."

I went away with a warm feeling in my heart for that kindly man who would have sacrificed his own comfort to insure the safety of an unprotected girl.

A few warm hand clasps, and interchanging of good wishes, a little dry feeling in the throat, a little strained pulsation of the heart, a little hurried run down the perpendicular plank to the other passengers who were going to London, and then the tug cast off from the ship, and we drifted away in the dark.

CHAPTER III.

SOUTHAMPTON TO JULES VERNE'S.

MR. amp; MRS. JULES VERNE have sent a special letter asking that if possible you will stop to see them," the London correspondent said to me, as we were on our way to the wharf.

"Oh, how I should like to see them!" I exclaimed, adding in the same breath, "Isn't it hard to be forced to decline such a treat?"

"If you are willing to go without sleep and rest for two nights, I think it can be done," he said quietly.

"Safely? Without making me miss any connections? If so, don't think about sleep or rest."

"It depends on our getting a train out of here to-night. All the regular trains until morning have left, and unless they decide to run a special mail train for the delayed mails, we will have to stay here all night and that will not give us time to see Verne. We shall see when we land what they will decide to do."

The boat that was landing us left much to be desired in the way of comfort. The only cabin seemed to be the hull, but it was filled with mail and baggage and lighted by a lamp with a smoked globe. I did not see any place to sit down, so we all stood on deck, shivering in the damp, chilly air, and looking in the gray fog like uneasy spirits.

The dreary, dilapidated wharf was a fit landing place for the antique boat. I silently followed the correspondent into a large empty shed, where a few men with sleep in their eyes and uniforms that bore ample testimony to the fact that they had slept in their clothes, were stationed behind some long, low tables.

"Where are your keys?" the correspondent asked me as he sat my solitary bag down before one of these weary looking inspectors.

"It is too full to lock," I answered simply.

"Will you swear that you have no tobacco or tea?" the inspector asked my escort lazily.

"Don't swear," I said to him; then turning to the inspector I added: "It's my bag."

He smiled and putting a chalk mark upon the bag freed us.

"Declare your tobacco and tea or tip the man," I said teazingly to a passenger who stood with poor, thin, shaking "Homie" under one arm, searching frantically through his pockets for his keys.

"I've fixed him!" he answered with an expressive wink.

Passing through the custom house we were made happy by the information that it had been decided to attach a passenger coach to the special mail train to oblige the passengers who wished to go to London without delay. The train was made up then, so we concluded to get into our car and try to warm up.

A porter took my bag and another man in uniform drew forth an enormous key with which he unlocked the door in the side of the car instead of the end, as in America. I managed to compass the uncomfortable long step to the door and striking my toe against some projection in the floor, went most ungracefully and unceremoniously on to the seat.

My escort after giving some order to the porter went out to see about my ticket, so I took a survey of an English railway compartment. The little square in which I sat looked like a hotel omnibus and was about as comfortable. The two red leather seats in it run across the car, one backing the engine, the other backing the rear of the train. There was a door on either side and one could hardly have told that there was a dingy lamp there to cast a light on the scene had not the odor from it been so loud. I carefully lifted the rug that covered the thing I had fallen over, curious to see what could be so necessary to an English railway carriage as to occupy such a prominent position. I found a harmless object that looked like a bar of iron and had just dropped the rug in place when the door opened and the porter, catching the iron at one end, pulled it out, replacing it with another like it in shape and size.

"Put your feet on the foot warmer and get warm, Miss," he said, and I mechanically did as he advised.

My escort returned soon after, followed by a porter who carried a large basket which he put in our carriage. The guard came afterwards and took our tickets. Pasting a slip of paper on the window, which backwards looked like "etavirP," he went out and locked the door.

"How should we get out if the train ran the track?" I asked, not half liking the idea of being locked in a box like an animal in a freight train.

"Trains never run off the track in England," was the quiet, satisfied answer.

"Too slow for that," I said teasingly, which only provoked a gentle inquiry as to whether I wanted anything to eat.

With a newspaper spread over our laps for a table-cloth, we brought out what the basket contained and put in our time eating and chatting about my journey until the train reached London.

As no train was expected at that hour, Waterloo Station was almost deserted. It was some little time after we stopped before the guard unlocked the door of our compartment and released us. Our few fellow-passengers were just about starting off in shabby cabs when we alighted. Once again we called goodbye and good wishes to each other, and then I found myself in a four-wheeled cab, facing a young Englishman who had come to meet us and who was glibly telling us the latest news.

I don't know at what hour we arrived, but my companions told me that it was daylight. I should not have known it. A gray, misty fog hung like a ghostly pall over the city. I always liked fog, it lends such a soft, beautifying light to things that otherwise in the broad glare of day would be rude and commonplace.

"How are these streets compared with those of New York?" was the first question that broke the silence after our leaving the station.

"They are not bad," I said with a patronizing air, thinking shamefacedly of the dreadful streets of New York, although determined to hear no word against them.

Westminster Abbey and the Houses of Parliament were pointed out to me, and the Thames, across which we drove. I felt that I was taking what might be called a bird's-eye view of London. A great many foreigners have taken views in the same rapid way of America, and afterwards gone home and written books about America, Americans, and Americanisms.

We drove first to the London office of the New York World. After receiving the cables that were waiting for my arrival, I started for the American Legation to get a passport as I had been instructed by cable.

Mr. McCormick, Secretary of the Legation, came into the room immediately after our arrival, and after welcoming and congratulating me on the successful termination of the first portion of my trip, sat down and wrote out a passport.

My escort was asked to go into another part of the room until the representative could ask me an important question. I had never required a passport before, and I felt a nervous curiosity to know what secrets were connected with such proceedings.

"There is one question all women dread to answer, and as very few will give a truthful reply, I will ask you to swear to the rest first and fill in the other question afterwards, unless you have no hesitancy in telling me your age."

"Oh, certainly," I laughed. "I will tell you my age, swear to it, too, and I am not afraid; my companion may come out of the corner."

"What is the color of your eyes?" he asked.

"Green," I said indifferently.

He was inclined to doubt it at first, but after a little inspection, both the gentlemen accepted my verdict as correct.

It was only a few seconds until we were whirling through the streets of London again. This time we went to the office of the Peninsular and Oriental Steamship Company, where I bought tickets that would cover at least half of my journey. A few moments again and we were driving rapidly to the Charing Cross station.

I was faint for food, and while my companion dismissed the cab and secured tickets, I ordered the only thing on the Charing Cross bill of fare that was prepared, so when he returned, his breakfast was ready for him. It was only ham and eggs, and coffee, but what we got of it was delicious. I know we did not get much, and when we were interrupted by the announcement that our train was starting, I stopped long enough to take another drink of coffee and then had to run down the platform to catch the train.

There is nothing like plenty of food to preserve health. I know that cup of coffee saved me from a headache that day. I had been shaking with the cold as we made our hurried drive through London, and my head was so dizzy at times that I hardly knew whether the earth had a chill or my brains were attending a ball. When I got comfortable seated in the train I began to feel warmer and more stable.

The train moved off at an easy-going speed, and the very jog of it lulled me into a state of languor.

"I want you to see the scenery along here; it is beautiful," my companion said, but I lazily thought, "What is scenery compared with sleep when one has not seen bed for over twenty-four hours?" so I said to him, very crossly:

"Don't you think you would better take a nap? You have not had any sleep for so long and you will be up so late to-night, that, really, I think for the sake of your health you would better sleep now."

"And you?" he asked with a teasing smile. I had been up even longer.

"Well, I confess, I was saying one word for you and two for myself," I replied, with a laugh that put us at ease on the subject.

"Honestly, now, I care very little for scenery when I am so sleepy," I said apologetically. "Those English farm houses are charming and the daisy-dotted meadows (I had not the faintest conception as to whether there were daisies in them or not), are only equaled by those I have seen in Kansas, but if you will excuse me?-" and I was in the land that joins the land of death.

I slept an easy, happy sleep, filled with dreams of home until I was waked by the train stopping.

"We change for the boat here," my companion said catching up our bags and rugs, which he hauled to a porter.

A little walk down to the pier brought us to the place where a boat was waiting. Some people were getting off the boat, but a larger number stood idly about waiting for it to move off.

The air was very cold and chilly, but still I preferred the deck to the close, musty-smelling cabin beneath. Two English women also remained on deck. I was much amused at the conversation they held with some friends who had accompanied them to the boat, and now stood on the wharf. One would have supposed, by hearing the conversation that they had only that instant met and having no time to spend together, were forced to make all further arrangements on the spot.

"You will come over to-morrow, now don't forget," the young woman on the boat called out.

"I won't forget. Are you certain that you have everything with you?" the one on the wharf called back.

"Look after Fido. Give him that compound in the morning if there is no appearance of improvement," the first one said.

"You will meet me to-morrow?" said number two on shore.

"Oh yes; don't forget to come," was the reply, and as the boat moved out they both talked at once until we were quite a distance off, then simultaneously the one turned to her chair and the other turned around and walked rapidly away from the wharf.

There has been so much written and told about the English Channel, that one is inclined to think of it as a stream of horrors. It is also affirmed that even hardy sailors bring up the past when crossing over it, so I naturally felt that my time would come.

All the passengers must have been familiar with the history of the channel, for I saw everyone trying all the known preventives of seasickness. The women assumed reclining positions and the men sought the bar.

I remained on deck and watched the sea-gulls, or what I thought were these useful birds-useful for millinery purposes-and froze my nose. It was bitterly cold, but I found the cold bracing until we anchored at Boulogne, France. Then I had a chill.

At the end of this desolate pier, where boats anchor and where trains start, is a small, dingy restaurant. While a little English sailor, who always dropped his h's and never forgot his "sir," took charge of our bags and went to secure accommodations for us in the outgoing train, we followed the other passengers into the restaurant to get something warm to eat.

I was in France now, and I began to wonder now what would have been my fate if I had been alone as I had expected. I knew my companion spoke French, the language that all the people about us were speaking, so I felt perfectly easy on that score as long as he was with me.

We took our places at the table and he began to order in French. The waiter looked blankly at him until, at last, more in a spirit of fun than anything else, I suggested that he give the order in English. The waiter glanced at me with a smile and answered in English.

We traveled from Boulogne to Amiens in a compartment with an English couple and a Frenchman. There was one foot-warmer and the day was cold. We all tried to put our feet on the one foot-warmer and the result was embarrassing. The Frenchman sat facing me and as I was conscious of having tramped on someone's toes, and as he looked at me angrily all the time above the edge of his newspaper, I had a guilty feeling of knowing whose toes had been tramped on.

During this trip I tried to solve the reason for the popularity of these ancient, incommodious railway carriages. I very shortly decided that while they may be suitable for countries where little traveling is done, they would be thoroughly useless in thinly populated countries where people think less of traveling 3,000 miles than they do about their dinner. I also decided that the reason why we think nothing of starting out on long trips, is because our comfort is so well looked after, that living on a first-class railway train is as comfortable as living at a first-class hotel. The English railway carriages are wretchedly heated. One's feet will be burning on the foot-warmer while one's back will be freezing in the cold air above. If one should be taken suddenly ill in an English railway compartment, it would be a very serious matter.

Still, I can picture conditions under which these ancient railway carriages might be agreeable, but they are not such as would induce a traveler to prefer them to those built on the American model.

Supposing one had the measles or a black eye, then a compartment in a railway carriage, made private by a tip to the porter, would be very consoling.

Supposing one was newly wed and was bubbling over in ecstacy of joy, then give one an English railway compartment, where two just made one can be secluded from the eyes of a cold, sneering public, who are just as great fools under the same conditions, although they would deny it if one told them so.

But talk about privacy! If it is privacy the English desire so much, they should adopt our American trains, for there is no privacy like that to be found in a large car filled with strangers. Everybody has, and keeps his own place. There is no sitting for hours, as is often the case in English trains, face to face and knees to knees with a stranger, offensive or otherwise, as he may chance to be.

Then too, did the English railway carriage make me understand why English girls need chaperones. It would make any American woman shudder with all her boasted self-reliance, to think of sending her daughter alone on a trip, even of a few hours' duration, where there was every possibility that during those hours she would be locked in a compartment with a stranger.

Small wonder the American girl is fearless. She has not been used to so called private compartments in English railway carriages, but to large crowds, and every individual that helps to swell that crowd is to her a protector. When mothers teach their daughters that there is safety in numbers, and that numbers are the body-guard that shield all woman-kind, then chaperones will be a thing of the past, and women will be nobler and better.

As I was pondering over this subject, the train pulled into a station and stopped. My escort looking out, informed me that we were at Amiens. We were securely locked in, however, and began to think that we would be carried past, when my companion managed to get his head out of the window and shouted for the guard to come to our release. Freed at last, we stepped out on the platform at Amiens.

CHAPTER IV.

JULES VERNE AT HOME.

M. JULES VERNE and Mme. Verne, accompanied by Mr. R. H. Sherard, a Paris journalist, stood on the platform waiting our arrival.

When I saw them I felt as any other woman would have done under the same circumstances. I wondered if my face was travel-stained, and if my hair was tossed. I thought regretfully, had I been traveling on an American train, I should have been able to make my toilet en route, so that when I stepped off at Amiens and faced the famous novelist and his charming wife, I would have been as trim and tidy as I would had I been receiving them in my own home.

There was little time for regret. They were advancing towards us, and in another second I had forgotten my untidiness in the cordial welcome they gave me. Jules Verne's bright eyes beamed on me with interest and kindliness, and Mme. Verne greeted me with the cordiality of a cherished friend. There were no stiff formalities to freeze the kindness in all our hearts, but a cordiality expressed with such charming grace that before I had been many minutes in their company, they had won my everlasting respect and devotion.

M. Verne led the way to the carriages which waited our coming. Mme. Verne walked closely by my side, glancing occasionally at me with a smile, which said in the language of the eye, the common language of the whole animal world, alike plain to man and beast:

"I am glad to greet you, and I regret we cannot speak together." M. Verne gracefully helped Mme. Verne and myself into a coupé, while he entered a carriage with the two other gentlemen. I felt very awkward at being left alone with Mme. Verne, as I was altogether unable to speak to her.