25,94 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Paraclete Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Serie: Paraclete Giants

- Sprache: Englisch

Published in over 6,000 editions before the year 1900, The Imitation of Christ has been more widely read than any other book in human history except the Bible itself. It has been called "the most influential work in Christian literature," "a landmark in the history of the human mind," and "the fifth gospel." Now, and for the first time, comes an exhaustive edition of this classic work, a work that is bound to become a classic in its own right. Fr. John-Julian introduces Kempis and his Imitation in ways that will shock many who have read the book before. For example, Protestant devotees to the book may be astounded to discover that Thomas was not only a Roman Catholic but an ardent traditionalist contemplative monk as well. And devoted Catholic readers may be amazed to discover that he was a radical moral reformer and part of a group twice formally charged with heresy. Notes and introductions to every aspect of The Imitation open the meaning of this classic to the next generation of readers.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 731

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

PARACLETEGIANTS

The COMPLETE IMITATIONof Christ

THOMAS KEMPIS

Translation and Commentary by Father John-Julian, OJN

PARACLETE PRESSBREWSTER, MASSACHUSETTS

The Complete Imitation of Christ

2012 First Printing

Copyright © 2012 by The Order of Julian of Norwich

ISBN 978-1-55725-810-6

The author uses his own translation of the Latin Vulgate for all Bible references unless specifically referenced as another version.

The scriptural references marked NRSV are taken from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright 1989, 1995 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of Churches of Christ in the United States of America and are used by permission. All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Imitatio Christi. English. The complete Imitation of Christ / Thomas Kempis; translation and commentary by Father John-Julian. p. cm.—(Paraclete giants) Includes bibliographical references (p. ). ISBN 978-1-55725-810-6 (trade pbk.) 1. Meditations—Early works to 1800. 2. Spiritual life—Catholic Church—Early works to 1800. 3. Catholic Church—Doctrines—Early works to 1800. I. Thomas, à Kempis, 1380-1471. II. John-Julian, Father, O.J.N. III. Title.

BV4821.J64 2012 242—dc23 2011050574

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in an electronic retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Published by Paraclete PressBrewster, Massachusettswww.paracletepress.com

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

NOTES ON THE TEXT

The Imitation of Christ and Annotation

BOOK ONE Advice Helpful to a Spiritual Life

BOOK TWO Warnings Drawing Us Inward

BOOK THREE Of a Devout Exhortation to Communion of the Holy Body of Christ

BOOK FOUR Of Inner Consolation

NOTABLE READERS OF The Imitation

NOTES

TIMELINE The Medieval Church in Europe

BIBLIOGRAPHY

This small, old-fashioned book, for which you need only pay sixpence at a bookstall, works miracles to this day, turning bitter waters into sweetness; while expensive sermons and treatises, newly issued, leave all things as they were before. It was written down by a hand that waited for the heart's prompting; it is the chronicle of a solitary, hidden anguish, struggle, trust and triumph—not written on velvet cushions to teach endurance to those who are treading with bleeding feet on the stones. And so it remains to all time a lasting record of human needs and human consolations; the voice of a brother who, ages ago, felt, suffered and renounced … with a fashion of speech different from ours, but under the same silent, far-off heavens, the same strivings, the same failures, the same weariness.

—GEORGE ELIOT, Mill on the Floss (1860)

INTRODUCTION TOThe Complete Imitation of Christ

Published in over six thousand editions by the year 1900—more than one new edition per month for over five hundred years1—The Imitation of Christ has been published more often and read more widely than any other book in human history except the Bible itself. Encyclopedia Britannica calls it “the most influential work in Christian Literature.”2 Canon Little called it “a landmark in the history of the human mind.”3 Jacques Bossuet called it “the fifth gospel,”4 and Fontenelle described it as “the finest work that has proceeded from the hand of man.”5

A further amazing aspect of this book's story is that while literally millions of people have read and re-read and meditated upon Kempis's words, most know virtually nothing about the author himself. Passionately Protestant devotees are astounded to discover that Thomas was not only a Roman Catholic, but an ardent traditionalist, contemplative monk as well; devoted Catholic readers are amazed to discover that he was a radical moral reformer and part of a group formally charged with heresy on two occasions.

Over the centuries since its composition, the book has suffered scores of copying errors, intentional excision of portions offensive to some particular tradition,6 the alteration or omission of seemingly incomprehensible Latin phrases (not recognized as Flemish idioms), rearrangement (and/or exclusion) of its books, and general literary wear and tear—both unintentional and malicious. As a result there are now nearly as many different versions of the volume as there have been translators. Add to this the fact that over the years the book has been credited variously to some thirty-five different authors,7 and the trail we need to follow to find anything like the genuine text is a considerable challenge.

In the years between 1410 and 1415, various anonymous collections and combinations of material that is now in The Imitation began to circulate somewhat privately among Carthusian and Cistercian monasteries in the Netherlands and Westphalia8: sometimes the treatises were promulgated separately and individually, sometimes a collection might include Book I and part of Book II, sometimes in reverse order, sometimes with the writings of Hendrik van Kalkar9 or Florens Radewyns interspersed between them.

The first broad public notice of material now in The Imitation occurred in 1416 when John Goswin, prior of the Augustinian monastery at Windesheim,10 attended the Council of Constance and took along an anonymous treatise entitled De converstione interna (that contained Book I and half of Book II of The Imitation). The tract became immediately popular and the copying began in earnest.11

Since the author of the material had not been identified, over the years various names arose asserting authorship. Prior Goswin's name morphed into “Geswin,” and “Gesen,” and finally was tied to a “John Gersen, Benedictine Abbot of Vercelli” or “Jean Charlier de Gerson, Chancellor of the University of Paris.” The Italian Gersen claim evaporated when it was found that no such person had ever existed! The French Gerson claim was vitiated by the presence of Kempis's recognizable style and Flemish idioms (some untranslatable into French) in the material at issue.

What is now called “The Kirkheim MS,”12 the earliest extant copy of the book, was found in the Royal Library at Brussels in the seventeenth century. It included Books I, II, and IV as well as this attestation clause: “Let it be noted that this treatise has been published by the good and distinguished man, Master Thomas of Mount Saint Agnes and a Canon Regular in Utrecht [diocese] called Thomas of Kempen. It has been copied from the hand of the author in Utrecht [diocese] in the year 1425 in the Society's Provincial House.”13

Meanwhile, the earliest surviving manuscript that includes all four books of The Imitation is the Gaesdonck MS now in the Volkshalle of Köln.14 At the end of the second book is the note: “On St. Elizabeth's Day in the year of our Lord 1425” and at the end of the last book is the note: “On Ss. Crispin and Crispian's Day in the year of our Lord 1427.” An 1852 description of this manuscript testified that it contains the name of the author as “Thomas of Kempen.”15

Finally, the first verified autograph manuscript that included all four books (and several other treatises) appeared publicly in 1441 in a Latin codex literally written by the personal hand of Thomas Kempis16 and signed with a final attestation: “Finished and completed in the year of our Lord 1441 by the hand of Brother Thomas Kempis in Mount St. Agnes near Zwolle.”17 That codex survives in the Royal Library of Brussels (#5855-5861). This present translation is based on the first printed edition (1471)18 and compared to a facsimile of the 1441 autograph codex,19 with very few corrections.

To make for further confusion, in 1921 a manuscript was discovered by the librarian Paul Hagen in the Library of Lübeck in northern Germany that had belonged to the Sisters of the Common Life and was apparently the spiritual diary of Gerhard Groote, the founder of the Brothers of the Common Life. This manuscript contained sixty stanzas that also appeared in Latin in The Imitation.20 This find seems never to have been given the scholarly attention it deserves.

Finally a study done by the Lutheran scholar Karl Hirsche of Hamburg in 1874 demonstrated convincingly that many portions of The Imitation had been written in a style of poetic rhythm uniquely common to other works known unquestionably to be by Thomas Kempis.21

In dealing with such a plethora of evidence, most modern scholars are generally satisfied that The Imitation as we have it today was written by Thomas Kempis at the Mount St. Agnes monastery near Zwolle in the Netherlands sometime between 1407 and 1441. The three-hundred-year-old controversy about authorship is far too vast and too irrelevant now to be related in detail here. (In fact, at least three entire books have been written simply on the authorship controversy22 and conclude that Thomas Kempis was the true author.) While I heartily agree that the book was Thomas's work, I cannot agree to his sole authorship for several reasons:

First, I fully credit the Lübeck manuscript as being authentically the work of Gerhard Groote. As Malaise has shown, it clearly parallels Groote's own spiritual development and matches his circumstances at each step in his life,23 and it contains nothing contrary to what we know of Groote's values and spiritual approach. It also had belonged to the Sisters of the Common Life for whom the works of their founder would remain of supreme importance. They would never have tolerated a counterfeit document.

Second, one of the spiritual practices initiated by Groote and carried on by all the followers of the Devotio Moderna (“the New Piety”—see below) was the keeping of books of raparia or adages, proverbs, maxims, and wise sayings that the members had encountered in their copying of the works of the Fathers, in their personal reading, or that had come to them in prayer and that they shared with their brothers.24 Many of the chapters of The Imitation are composed of exactly such collections of spiritual insights, and, indeed, in many cases there is little or no logical link between two proximate chapters, each of which seems to be a totally independent grouping of thoughts, insights, or advice, with no evidence of consistent authorship style or language.

Third, as translator I can attest that no one person could possibly have written all that is in The Imitation. The variety of Latin is incredible, ranging from passages in the simplest schoolbook Latin, through sections of purely classical composition, to others of breathtakingly elegant literary rhetoric, and to some of impure, late, and irregular Latin, contaminated by local patois and idiom.25 It seems clear to me that this was an exhaustive compilation of materials from differing and assorted sources written by more than one author (in my opinion at least three).26

Fourth, there are many passages in The Imitation written in rhymed poetry, others that flow in a highly rhythmic fashion, but many others that are in rigid and almost severe prose. The variation in style is vast between stern, judgmental harangues, reprimands, and dire threats, on the one hand, and gentle, loving concern and soothing sympathy on the other. There are grace-filled paeans of praise for love or for the glories of heaven, and also dark threats and fearsome intimidations. Some chapters are almost entirely literal quotations from Scripture; others have no scriptural references at all. Such extremes of composition from a single hand seem at best unlikely.

Fifth, scattered through the book are Flemish idioms that make little sense in Latin unless one is familiar with the dialect and is warned by what appears to be untranslatable or erroneous Latin. It seems to me that some of the book was probably originally written in Flemish or Low German and translated into Latin for publication.27

Sixth, at least one commentator has declared: “Thomas a Kempis in the year 1424 set himself to the task of compiling and editing the writings of the Brethren of the Common Life” (emphasis mine).28

Seventh, the text of a surviving letter in Latin written no later than 1382 (the date of its writer's death) by a Dutch Canon Regular, Johann van Schoonhoven, is so close to the text of Book I of The Imitation that it cannot be explained in any other way than by replication. Since in 1382 Thomas Kempis would have been only two years old, the only conclusion is that in The Imitation, Thomas copied from Schoonhoven's letter (or both from a common earlier source).29 This is absolutely not a judgment of “plagiarism” against Thomas, however, since all work of the Canons Regular was considered to be common property to be used freely (and anonymously) for the good of the whole.

Eighth, several passages in The Imitation are confessional and self-accusatory in nature, and the author charges himself of having lived in opulence, having cared more for things of the world than for God, having been concerned only for his own pleasure and comfort. It is simply impossible to imagine that the simple and austere Thomas Kempis, who lived as a Brother of the Common Life or as a Canon Regular from the age of thirteen until his death over seventy-eight years later (and left the monastery only twice in all those years), could ever—even given rhetorical hyperbole—have lived the luxuriant and self-indulgent life of which the author accuses himself (whereas the self-accusations exactly describe Gerard Groote's decadent life before his conversion).

Ninth, there are several places in The Imitation (notably Book I, Chapter 22) where the subject in the Latin text without notice changes several times from first person plural to second person plural (that is, from “we” and “us” to “you”) and back again. It seems likely that some of the text was authored by the compiler (Thomas) and some by another author or authors.

Finally, there are some eight contemporary witnesses who assert that Thomas was the writer, not necessarily the author: that is, scriptor, not auctor of the four separate treatises that were brought together to form The Imitation.

My own conclusion (shared with at least two scholars30) is that Thomas Kempis was without any doubt the editor, compiler, and partial author of The Imitation of Christ. And although I would hesitate to make a specific verse-by-verse attribution by comparing this book with other of Thomas's works, I am convinced that the more simple, gentle, loving, forgiving, and exulting portions of the book are probably authored by him, and the rest by Gerard Groote and/or other proponents of the Devotio Moderna movement and the Brothers of the Common Life.31

But to understand the historical setting and impact of this significant volume, it is necessary for us to take a step backward—to August 20 in the year 1340 when Gerard Groote was born in Deventer in the Netherlands.32

GERARD GROOTE[Gerardus Magnus] 1340–1384

Although he is universally referred to as “Gerard Groote,” his name simply means “Gerard Great” in Flemish (Gerardus Magnus in Latin), and “great” he was!33 He was born the son of Werner Groote, the sheriff and mayor of Deventer—an independent city-state, a major center of trade, and a famous seat of learning. The boy excelled in his studies in the local cathedral Chapter School. He went on to higher studies in the great cathedral city of Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle) and then, when he was only fifteen, to the Sorbonne in Paris where he studied medicine, astronomy, theology, canon law, and even astrology and magic (which was considered a respectable aspect of science studies at the time).34 He graduated from the Sorbonne in 1358 with a Master of Arts degree and went on to pursue doctoral studies at the Universities in Köln and Prague. An anonymous biographer wrote: “So great was his knowledge and wisdom that he was second to no one in the entire world in his time; who was more influential in the liberal arts and moral theology, who more eminent in canon law than he?”35

In 1362, Groote returned to Deventer as teacher in the Chapter School. In 1366, at the age of twenty-six, he was so well-thought-of that he was sent as a secret ambassador from the city of Deventer to the papal court of Urban V at Avignon. Soon afterward he joined the faculty of the University in Köln, and was granted the (very considerable) incomes of two canonries in Utrecht and Aachen. While his fame as a brilliant scholar spread, he began to live a life of secular extravagance and luxury.36

In 1374, however, he fell seriously ill with a life-threatening sickness. His confessor required that he burn all his precious manuscripts on magic and astrology before he would administer Last Rites. Groote had barely recovered when he was visited by a fellow-student from the Sorbonne, Hendrick Ægher van Kalkar, who had become prior of the Carthusian monastery at Munnikhuizen near Arnhem on the Rhine and was a man of deep piety. He remonstrated with Groote about his opulent excesses.

During this time Groote also made several visits to the hermitage of the famous Flemish mystic Jan van Ruysbroek at Groenendaal near Brussels. Ruysbroek eventually became Groote's primary spiritual influence; he wrote: “My heart is welded to him beyond all other men by love and reverence. I do still burn and sigh for his presence, to be renewed and inspired by his spirit and to be a partaker thereof.” It was probably on Ruysbroek's advice that Groote made the decision to retire to the monastery.

Shaken by his brush with death and stirred by his friend's counsel, in 1376 Groote undertook a complete conversion of his life. He made a Life Confession of past sins, completely repudiated his previous luxuriant lifestyle, left his post at the University, resigned his prebends, and gave away all his belongings. Groote withdrew to the Munnikhuizen monastery where (although he did not actually take monastic vows) he began to live devoutly, abstaining from meat and wearing a hair shirt.37 He lived the Carthusian life there for three years in recollection and prayer. It was at that time and place that the spirituality of the Devotio Moderna with its “practical asceticism” was born in Groote's mind and heart.

Then in 1379—at the instigation of the monks—he approached the bishop and was ordained deacon38 and licensed as a missionary to preach wherever he wished in the diocese of Utrecht. And here his “New Piety” (Devotio Moderna) began to take practical shape. Groote came out of his monastic retreat, alive with an evangelistic fervor and a vibrant skill in preaching. His success was immense. People shuttered their businesses and skipped meals in order to hear his sermons. Eventually the churches could not contain the crowds that gathered to hear him, although he often preached as long as three hours—and twice in a day! Groote had signed away ownership of his own family mansion in Deventer to the city aldermen to serve as a hostel for poor women, reserving only one small apartment for himself. Using his brilliant familiarity with civic and canon law, Groote was eventually able to establish a unique formal charter and statutes to protect and govern the house after his death. Under these agreements the women were not allowed to take monastic vows or wear any special clothing. They were to have a matron (called the Martha) who served to oversee the house and its finances. Strictly speaking, this was a “hostel,” but it became a “Sister-House” after Groote's death.

More and more communities of women began to come together in cities across the Netherlands and in Germany, inspired by Groote's ideas and following his “rule.” (Eventually, over the next two generations, there were over a hundred and fifty women's houses of various sorts.)

The young Florens Radewyns, Groote's favorite disciple, once approached his mentor: “Master, why not put our efforts and earnings together? Why not work and pray together under the guidance of our common Father?” Groote replied with alarm, “Live together! The Mendicants [religious orders] would never allow it!” Radewyns persisted, “But what is to prevent our trying? Perhaps God will give us success.” Groote's reaction was momentarily hesitant and then increasingly enthusiastic, and the two set to work immediately and soon devised and established what was to become “The Brothers of the Common Life.” Radewyns opened his vicarage to house young scholars, a second house was obtained, and the new community began its life in what was to be called “The Brother-House.”39

Two problems arose: first, Groote's preaching against the ignorance, corruption, simony, and other vices of the clergy made him highly unpopular with many of the ecclesiastical powers. In 1383, following his sermon to a conference of bishops and high church officials in Utrecht,40 his license to preach as a deacon was revoked.41 Second, the new Brothers of the Common Life also encountered serious opposition, because its members were not under vows and owed formal allegiance to no one except Christ. Traditional monastic orders began an unremitting complaint, demanding that the Brothers either take monastic vows or disperse their communities and live “normal” lives.42

Groote finally made the decision to apply to the pope for formal ecclesiastical approval of the Congregations of the Common Life, and as a protective “front” or “cover” he also decided to gather some of the Devout and have them recognized as formal Canons under the established Rule of St. Augustine to found a proper monastery.43 So he went off with Radewyns and some of his disciples to the Nemel Hills (about five miles from Zwolle) and selected a site for this Augustinian House.

However, in the midst of the controversy and before his plans could be realized, a dear clerical friend, Lambert Stuerman, was stricken by the plague. Groote ministered to his friend, and in doing so contracted the pestilence himself. Approaching death, he called Radewyns to his bedside and urged him to build the proposed monastery as soon as possible, and then, after receiving the Viaticum, on August 20, 1384, at the young age of forty-four, he died, having initiated a renaissance of devotion and piety that swept over all of Europe and reached significantly into the future.

CONGREGATIONS OF THE COMMON LIFE44

When Florens Radewyns became leader of the movement, there were two Common Life houses in Deventer—his own vicarage (that housed poor young scholars who were attending Deventer schools) and another house for men—and the hostel for women that had been established as a Sister-House in Groote's own home.

These communities lived very simple lives without adornment or extravagance. Their intention was to reproduce the communal lives of the first Christians as recorded in the fourth chapter of the Acts of the Apostles. They lived together and, forbidden to beg for alms, they all did manual labor of some kind to earn enough income to cover their needs. The Sisters supported themselves mainly by gardening, baking, brewing, lace-making, spinning, sewing, and weaving; originally the men's work was primarily the copying of manuscripts.45 Later, after printing was invented and the demand for copying fell off, the Brothers took up printing and founded hundreds of schools across Holland and Germany so that eventually their major work became teaching and the management of these schools.

In 1386, two years after Groote's death (and obeying his last wishes), Radewyns sent six of the Brothers from his house to establish a formal congregation of Augustinian Canons at Windesheim down the Ijssel river valley, about forty miles from Deventer where the bishop had donated some land. Among these founders was John, the elder brother of Thomas Kempis. So, from that time on, there were two “orientations” or “branches” of the Devotio Moderna movement who, although they maintained very close relations, represented two separate traditions of Christian community: the simple, laity-based, neighborhood-house and schoolboy-hostel without vows, on the one hand, and the more formal, vowed, contemplative monastic tradition, on the other (although it is clear that the Brother-House also served as a “feeder” to the Augustinian Canons).

“[The Devout communities] were an alternative community, always perceived as slightly odd, often somewhat on the defensive. At the same time towns came to take their presence and work more and more for granted.”46

BROTHERS OF THE COMMON LIFE47

The House Brothers were expected to wear simple clothing—eventually a gray smock and cloak. They ate simple meals, provided alms and food for the poor and needy, and paid for the education and provided housing for poor boys whose families could not otherwise afford schooling. All the Brothers attended parish churches for Mass (although they had their own chapels for daily prayer and the Offices). Brothers who were priests engaged in preaching and occasionally served as parish pastors. As time went by, the schools of the Brotherhood spread far and wide throughout the Netherlands, Germany, and France, and eventually these schools trained many of the major leaders of later reform: Luther, Zwingli, Calvin, Melancthon, Bucer, Bez, Erasmus, and even the map-maker Mercator.48

The Bible was read during mealtimes by the rector, who, to make sure of people's attention, could question anyone present about what was being read. One was expected to offer up short prayers at all times of the day and to set oneself particular spiritual tasks, such as praying whenever one heard a clock chime. Perhaps most important was the process of continuous meditation, or rumination. The master would set a subject each day—say, the passion of Christ—and everyone was to ponder it all day long.

Then there were communal meetings where correction took place. Members were invited to accuse themselves of their faults, and anyone in the group was expected, with due humility, to reveal anything he knew of another person's faults—the model of a monastic Chapter of Faults.

The Brothers' main literary efforts went into biographies and handbooks rather than sustained mystical treatises. The biographies were of exemplary lives preserved for moral education; the handbooks were either guidelines for everyday spirituality or collections of useful sayings and exercises.

There was always opposition to the life and work of the Brothers and Sisters. In most cases, this opposition came from clergy whose decadent lifestyle had been challenged by the Brothers' preaching or by monastics who resented the relative freedom of the Brothers and Sisters. Whenever such opposition or charges arose, the matter was referred to the canon law faculty at the University of Köln that in all cases judged strongly in favor of the Brothers/Sisters. In 1418, however, Matthias Grabow, a German Dominican of Gröningen, brought twenty-five formal heresy charges against the Brothers at the Council of Constance49 (the substance of which charges was that Christian communal life had to be lived only within officially sanctioned formal religious orders). However, a commission appointed by the pope revoked the charges. Grabow refused to retract his allegations, was imprisoned, and died two years later. The new pope, Martin V, gave his enthusiastic approbation to the Brotherhood.50

The Brothers were not crude revolutionaries. They had no wish to overthrow the Catholic Church system in any way—they only wanted to get rid of its corruption.51 It is important to note that the Brothers' reforms were not done on the sly. Indeed, they were often asked to take responsibility for reform in other monasteries and to provide priests for parish churches. They were clearly effective: when Martin Luther and his reforming colleagues were preaching anticlericalism around 1520 and condemned monastics, these reformers specifically excluded the Brothers from their censure, as being manifestly not corrupt. It is interesting that there was apparently no evangelistic motivation in the life and work of the Devout; in an almost Benedictine way, they saw themselves as establishing “islands of grace,” not engaged in preaching or other ministries—welcoming new members, but not evangelizing.

THEDEVOTIO MODERNA

The label of Devotio Moderna came to be applied to the spiritual approach initiated by Gerard Groote and carried on by the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life and the Augustinian Canons founded by Groote's followers.52 The term has been variously translated, but basically means “The New Piety.”53

Although the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life were formally charged twice with heresy by the Inquisition,54 they were totally exonerated in each instance. And, although many modern writers like to think of them as forerunners of the Reformation, in fact, they had very little in common with the early Protestants.

In order to comprehend their “New Piety,” it must first be understood that the Brothers and Sisters were enthusiastically and unbendingly orthodox Catholics, with unqualified commitment to the doctrine and liturgical practices of the Roman Catholic Church of their day. This cannot be stressed sufficiently. The Brothers and Sisters strongly supported the practice of indulgences, celebrated the possession of the relics of saints, preached a strict doctrine of transubstantiation, promoted frequent Confession, dutifully followed and obeyed the pope, and in every way represented faithfulness to the Roman Church and its teachings. I have scoured all surviving works of the Devotio for anything that might even hint at a departure from or a compromise of Catholic faith and practice, and I have found nothing. The Brothers and Sisters' only criticisms were never of the Church, but of individual churchmen whom they accused of self-seeking, corruption, simony, concubinage, and moral compromise.

The major emphasis of the New Piety teachings was on conversion, meditation, discipline, and the deeply spiritual personal life lived daily. In effect, they strove to provide an inner spiritual and moral maturity in congruence with external practice.

In this process, the word conversion came to be central, referring to the beginning point of spiritual development. It implied a person's choice to move from an empty and inattentive mouthing of religious clichés and an insincere practice of church ritual to a vital, transforming commitment to moral purity and inner spiritual growth. The Devotio Moderna called for deep and constant introspection, serious private (and corporate) self-accusation, simple moral discipline, and extended meditation on Scripture and the writings of the Church Fathers. The Brothers and Sisters believed that they were simply restoring the early Christian customs and practices of the apostolic Church and the monastic Desert Fathers and Mothers.

Radewyns had compared a human being with a musical instrument: humans in their present state were “out of tune” with God. When one was truly converted, one's inadequate and imperfect affections and emotions were changed into pure love, and one can then love God for God's own sake.

All the strict ascetic disciplines of fasting, sleep-deprivation, hair shirts, and all the meditative reading of holy texts and the prayers were primarily oriented toward the abolition of sin that was, of course, an obstacle to love (and that loomed large in the Devotio). The Devout cannot escape the accusation of dualism, in which the world and the flesh was seen as wicked, and all things spiritual as good. As a result, the Devout “set experience over intellect, devotion against cognition, charity against learning.”55 Their main goal was to develop the sanctity of the individual (especially lay) Christian. Neither evangelistic preaching nor concern about political, social, or economic conditions held any significant place in their teaching and practice. They looked inward and were concerned almost exclusively with individual virtue and spiritual growth.

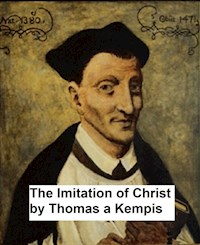

THOMAS HAMERKEN56[Thomas Kempis]

By an early linguistic error, Thomas has come to be known almost universally as “Thomas à Kempis.” He came from the town of Kempen in the diocese of Köln in the Rhineland (now Germany).57 When he became an Augustinian Canon and began to write, he Latinized his name to Thomas Kempensis (literally, “Thomas of Kempen”) and that came to be abbreviated to Thomas a Kempis or simply Thomas Kempis. (The “a” is Latin for “from”—and if it is used, it should never be accented.) His name in Dutch is van Kempen; in German von Kempen; and in French de Kempen. I have chosen to use the simplest form “Thomas Kempis” that Thomas himself used in signing his own copy of The Imitation and his translation of the Bible.58

Thomas was born in late 1379 or early 1380 in Kempen (about thirty miles northwest of Köln) in the Rhineland, the son of John and Gertrude Hemerken.59 His father, Johann, was a laborer (possibly a metal worker), and his mother (Gertrude Kuyt) kept the “dame's school” for the younger children of the town. We know of only two children in the family: John (about fourteen years the senior) and Thomas.60

While Thomas was very young, his brother John left home to attend a popular and renowned school in Deventer in the Netherlands.61 Around 1392, when Thomas was thirteen, he also traveled to Deventer to see his brother. He arrived at the Brother-House where John had lived, only to discover that, apparently unbeknownst to his family, two years previously John had been among the six founders of the Windesheim monastery and had become an Augustinian Canon Regular and left Deventer.62

Thomas sought him out there, and John sent his brother back to Florens Radewyns in Deventer for his schooling. Radewyns gave him a room in his own vicarage and sent him to the Latin academy led by John Boehm. Thomas was penniless, but Radewyns gave him money for tuition. However when Boehm learned of it, he returned the money, and kept the boy on free tuition.

Thomas's closest friend was Arnold of Schoonhoven. “For nearly a year Arnold and I dwelt together in close companionship, occupying the same small room and the same bed,” Thomas wrote in the brief biography of Arnold that he included in his later book The Founders of the New Devotion … and Their Followers.

After that first year, Radewyns arranged housing for Thomas with “a certain and devout noble lady who showed much kindness both to me and to several other clerks,” and Thomas remained in the Deventer schools for seven years, eventually moving back to “The Florens House.”

Meanwhile, in 1398, the Canons Regular at Windesheim had established and built a new daughter house three miles away at Mount St. Agnes near Zwolle, and John Kempis was elected first prior of the new monastery.

When Thomas finished his education in Deventer in 1399, he presented himself at Mount St. Agnes as a donatus, asking to join his brother's monastery.63 In the next year, Thomas's beloved mentor, Florens Radewyns, died. And apparently Thomas also lost his parents three years later since we know that in 1403 the brothers Hamerken had to travel the seventy-five miles to Kempen to make arrangements for the sale of their parents' home.

In 1406 Thomas was clothed as a novice,64 and soon afterward his brother, John, left Mount St. Agnes to serve as first prior of the new monastery at Haarlem. It seems likely that at this time Thomas began to collect materials that would later appear in The Imitation.65

By special dispensation of the monastery Chapter, Thomas's novitiate was shortened and he was allowed to profess Life Vows in 1407. This abbreviation of the novitiate was an indication that Thomas's spiritual integrity and piety must have been exceptional even at that early point. By about 1413, Thomas was ordained as a priest and may have compiled the first book of The Imitation. He also soon began another magnum opus when he commenced copying the Vulgate Bible (that would take sixteen years to complete).66

In 1421 the plague broke out in Deventer and Zwolle. Thomas tells of several deaths in his Chronicle of St. Agnes: the community's miller, a lay-brother carpenter, the infirmarian, a lay associate, a priest of the order, and another priest who served as confessor to the Sisters in Hasselt. But Thomas was spared.

In 1425 he was elected sub-prior (that is, second in command) and novice master (in charge of training novices) at Mount St. Agnes.67 And four years later the only event of great significance during his long life at St. Agnes occurred: the Papal Interdict. Contrary to the express wishes of the majority of the electors (who had chosen Rudolf van Diepholt), Pope Martin V named Sweder de Culenborgh as bishop of Utrecht. The people of Zwolle and Deventer refused to accept him, and the pope placed the two cities under an interdict by which the sacraments were not to be administered in the diocese, and no one was to be buried with a church funeral. The Canons at Mount St. Agnes decided to observe the interdict, and they were virtually driven out of their monastery by the angry populace. They fled by night the five miles to Hasselt and there took ship for Frisia and finally made their way to the monastery at Lunenkerc (outside the diocese of Utrecht).

Thomas remained there with his exiled brothers for two years, but in the autumn of 1431 he was called to the convent of Bethania near Arnhem where his brother, John, had been prior. John was very seriously ill, and Thomas nursed him for fourteen months until his death in 1432.68

Meanwhile, Martin V had died and been replaced by Eugene IV, the interdict had been lifted, and the Canons had returned to Mount St. Agnes and elected new officers. Consequently, when Thomas returned to the monastery after burying his brother, he found that he was no longer sub-prior or novice master, but he was made Procurator (treasurer) of the house. He soon begged to be relieved of the office pleading that he was inept with temporal matters, and when the post of sub-prior became vacant again in 1448, he was re-elected. As far as we know, from 1432 until his death Thomas never left the monastery grounds.

During his monastic life, Thomas wrote thirty-one books, treatises, and articles including a chronicle of his monastery and several biographies—lives of Gerhard Groote, Florens Radewyns, a Flemish lady St. Louise (Liduina), and of several of Groote's original disciples; a number of tracts on the monastic life—The Monk's Alphabet, The Discipline of Cloisters, A Dialogue of Novices, The Life of the Good Monk, The Monk's Epitaph, Sermons to Novices, Sermons to Monks, The Solitary Life, On Silence, On Poverty, Humility and Patience; two tracts for young people—A Manual of Doctrine for the Young, and A Manual for Children; and books for spiritual edification—On True Compunction, The Garden of Roses, The Valley of Lilies, The Consolation of the Poor and the Sick, The Three Tabernacles, True Wisdom, The Imitation of Mary, The Inner Life, Counsels on the Spiritual Life, On the Passion of Christ, and Consolations for My Soul. He also left behind him three manuscript collections of sermons, a number of letters, some hymns and, of course, the famous The Imitation of Christ.

In 1441 Thomas completed his final compilation of The Imitation written in his own hand, and with his personal attestation at the end of the manuscript (that also included nine other compositions of his). The four treatises in The Imitation had been written independently, and they had circulated far and wide for a long time (some scholars claim as long as thirty years), sometimes separately, and sometimes in various combinations before Thomas finally brought them all together in this manuscript.

As Thomas advanced in age, he suffered badly from the pains of dropsy (now known as edema, that is, the swelling of the legs and feet), but his vision remained clear, and he boasted of never having to use spectacles. In 1471, just before his death at the end of July, Thomas had what must have been the singular joy of seeing his The Imitation of Christ published by Günther Zainer at Augsburg—one of the earliest books ever printed.69 Franciscus Tolensis, a Canon Regular at Mount St. Agnes monastery (c. 1575) who wrote a biography of Thomas, tells of seeing an old painting of Thomas with the motto of mixed Latin and Flemish at its foot: In omnibus requiem quaesivi, sed non inveni, nisi een Hoexkens een Boexkens. (“In all things I have sought peace, but I found it not except in a little corner with a little book.”)70

Thomas's body was buried at the eastern end of the cloister at Mount St. Agnes where he had spent seventy-two contented years. During the upheavals of the Reformation, however, around 1570 the Canons left for St. Martin's Priory at Louvain, and the monastery stood empty. In 1577 the library (including the 1441 autograph manuscript of The Imitation) was rescued by Johannes Latomus, prior of the Monastery of the Throne near Herentehals. When he died, Johannes left the codex to a learned friend Jean Bellère who gave the manuscript to the Antwerp Jesuits in 1590.71 In 1591, the Jesuit Order was suppressed and the manuscript was given to the Burgundian Library at Brussels. The monastery buildings at Mount St. Agnes fell into disuse and were left to ruin.

In 1655 when Alexander VII became pope, he intended to canonize Thomas Kempis, but at the time no one could locate his remains.

However, when the Catholics retook possession of the Netherlands, the leaders immediately set out to find Thomas's relics. They were guided by a local recollection, handed down carefully from pastor to pastor,72 and thus in 1672 Maximilian Heinrich, Archbishop of Köln, was able to find the relics in exactly the location tradition had described. They were then carried in procession to the Chapel of St. Joseph in Zwolle where, in 1674, the archbishop provided a handsome reliquary, and attempted to start the canonization process. However, after his death in 1688, the matter was never advanced.73

More than a century later, in 1809, when the St. Joseph Chapel was abandoned, the relics were moved to the sacristy of St. Michael's Church outside Zwolle.74 In 1897, an elegant marble shrine was raised there, paid for by world-wide subscriptions and inscribed Honori, non memoriae Thomae Kempensis, cujus nomen perennius quam monumentum (“To the honor, not just to the memory, of Thomas of Kempen, whose name is more enduring than any monument”).

In 1911, Monsignor van Valen, Dean of Zwolle, in an audience with Pope Pius X, once again broached the possibility of canonization, but at that time the authorship of Thomas's great book was being contested by scholars, and the pope declared he could not be assured of Thomas's precise authorship and the matter was dropped.

Finally, in July of 2006 when St. Michael's Church was closed and pulled down, the reliquary containing Thomas's remains was carried in solemn procession to a new shrine in the Basilica of Our Lady of the Assumption, Zwolle (locally called Basiliek de Peperbus—“Basilica of the Pepper Pot”—because of the unusual design of the tower that looks like a pepper shaker).

In 1901 his hometown of Kempen erected an impressive statue of Thomas beside the parish church.75

NOTES ON THE TEXT

Translation of any text from any language is a challenge, and no translation can ever be “perfect,” because there is no conceivable way to capture the subtle nuances and unconscious associations that a word or phrase may have for its native writers and to make those explicit to an alien reader. For instance, the definitions of the single Latin word volo take up twenty-two full columns in the massive Lewis and Short dictionary—with a hundred and nine entirely separate definitions!76

In the case of The Imitation of Christ this is further complicated by the fact that some of the material may possibly have been written originally in Flemish, translated into Latin, and here translated a second time into English. Consequently, there are phrases and clauses in a Flemish idiom that are often in very poor Latin.

Of course, the only Bible available to the author of The Imitation was St. Jerome's Latin Vulgate Bible (indeed, it was Thomas's Augustinian Canons Regular who collected, corrected, and collated several differing Latin versions into the one Vulgate that was formally approved by the Catholic Church at the close of the fifteenth century).77 In this present book I use my own translation of the Latin Vulgate for all Bible references unless otherwise noted. There is some confusion that may result from this practice:

(a) The numbering of the Vulgate Psalter differs from the more familiar sequence, so I have used the translated Vulgate version and added in brackets the number of the psalm from the 1979 Book of Common Prayer.

(b) The names of some books of the Vulgate may also be unfamiliar: for example, 1 and 2 Samuel and 1 and 2 Kings are 1, 2, 3, and 4 Kings in the Vulgate; the “Book of Zephaniah” is the “Prophecy of Sophonias” in the Vulgate; 1 and 2 Chronicles are 1 and 2 Paralipomeno, and so forth. In every case I have used the Vulgate title and bracketed the familiar title.

(c) Since the Vulgate was Thomas's Bible, I have retained the Latinate quality of the translation throughout rather than adapt it to full, modern, and familiar use. Consequently, in some instances the language may seem somewhat stilted or artificial, but it captures the character and integrity of the original better than a modern idiom.

All translations of other Latin, Greek, or French documents referred to in the book are my own unless otherwise indicated.

Thomas has frequently used the generic masculine “man” (homo) or “son” (filius). I have tried where it is grammatically possible to replace that with “person,” “human,” “mortal,” or “child,” but it has been impracticable in many places to replace the pronoun “he,” “him,” or “his.” Apologies are offered and grammatical structure must take the blame!

The order of the four books presents another editing conundrum. In Thomas's original 1441 autograph codex and in the 1471 first printed edition, the book on the Blessed Sacrament was placed as Book III. However, in the dozens of English translations (excepting Liddon's in 1890 and Elder Mullan's in 1908), that book is placed as Book IV I suspect this is because there were several very early copies that circulated with only three books, omitting the one on the Mass. In later copies it was intentionally left out, because its teaching was theologically awkward for some Protestants. In this translation, however, I have restored the wandering book to its original position as Book III. Readers are reminded that citations from other sources, therefore, may not correspond with this edition: their “Book III” may be “Book IV” here, and vice versa.

Also, in the 1471 first printed edition, the chapter numbering in Book IV was somewhat altered from the more ancient codex. Since that printed version was known by Thomas Kempis himself just before he died, I have followed that later numbering. Similarly, the paragraphs or stanzas and their numbering were instituted in the 1599 edition of Henry Sommalius, SJ, and that numbering has been almost universally imitated in editions ever since. However, as the Dublin Review of 1880 put it: “Both paragraphs and versicles are extremely defective and tend to obscure rather than elucidate the text by separating kindred passages that naturally cohere, and approximating others that sensibly diverge.”78 Consequently, in this edition, I have removed those extraneous and unhelpful numbered divisions in the text.

The author of The Imitation used a peculiar system of punctuation that does not correspond to modern systems. Apparently these were attempts to provide guidance for those reading the text aloud. In all cases, the punctuation resembles the notes in Gregorian Plainchant: (a) a comma (that looks like a Gregorian clivis) indicates a very slight pause; (b) a colon (that looks like a Gregorian podatus) a bit longer pause; (c) a semi-colon (that looks like a Gregorian salicus) a still longer pause; (d) a flexus (an original punctuation that looks like a Gregorian torculus) indicates an even longer pause; (e) a period (such as a Gregorian punctum, although commonly above the font's base line) followed by a lower-case letter indicates the longest pause; (f) a period (punctum) followed by a capital letter shows the end of a sentence; and (g) a question mark (that looks like a Gregorian scandicus) indicates an interrogatory. I have not tried to reproduce these punctuation marks in the modern text, but I have divided the lines on the basis of this unique punctuation.79

In many places the language is very rhythmical and almost musical in its Latin phrasing. Chapter 7 of Book II, for instance, is one of the finest and most beautiful paeans to the love of Jesus in all Christian literature. In order to demonstrate those places where actual rhyming occurs, I have added the following symbols after words or lines that rhyme in the Latin: Δ, √, Ω, ∫, §, ≈, ß ∞, ∂, μ, ƒ, Π, Σ and †.

The attributions within the text—“The Soul speaks” or “God speaks”—are not present in the original codex. They are added for clarification.

It will be noted that there are many instances when the language of the text carries a monastic meaning not immediately evident to lay persons. For example, the word Devout is often a noun referring to one of the Brothers of the Common Life or one of the Augustinian Canons who called themselves “Devouts”80; or the Latin parvuli, novi, novissimi, “little ones” or “new ones” or “newest ones” here frequently refer to monastic novices. I have tried to point them out.

The book is full of “catalogs,” that is, long lists of sins or virtues or adjectives that often seem to be exercises in rhetorical prose rather than a religious thesis. In I:24, for instance, Tunc is repeated seventeen times; in IV:7, Tam is repeated thirty-seven times.81 There are also whole chapters of the book that seem to be simply collections of adages, aphorisms, and epigrams, and it seems to me that these may well have been the accumulated rapiaria or commonplace books of Thomas or others of the Devout. This might also explain the diary-like, highly personal lamentations, confessions, and revelations that occur in several places.

BOOK ONE

ADVICE HELPFUL TO A SPIRITUAL LIFE

COMMENTS ON CHAPTER 1

a. The introductory material explains the complexities of the author's name. I have chosen to use the Latin form “Thomas Kempis,” which was what Thomas himself used in his manuscripts.

b. Most Carthusian manuscripts (the earliest ones outside of the Windesheim circle itself) and the early English editions of the book were oddly entitled Musica Ecclesiastica (“Church Music”), probably because of the rhythmic (and occasionally rhymed) nature of the original text and Thomas's use of what appears to be musical notes in some of his punctuation. What has come to be the common name—Of the Imitation of Christ—is simply taken from the first words of the title of the first lines of the first book.

c. John 8:12—“…he who follows me does not walk in darkness”

d. We know from Thomas's other works that in addition to the Scriptures, the writings of the Fathers of the Church (especially St. Augustine and St. Bernard) were his constant reference, and he had made copies of their works.

e. Revelation 2:17b—“To him who overcomes I will give the hidden manna…”—a reference to unspecified spiritual rewards.

f. Romans 8:9—“Now if any man does not have the Spirit of Christ, he does not belong to him.”

g.Sensibly in the Latin is sapide and can also mean “appetizingly” or “prudently.”

h.Displease in the Latin is displiceas and can also mean “make ill.” The poetic literary parallel of dispute with displease is clearly intentional even in the Latin.

i. A curious Flemish idiom: the Latin has Si scires totam bibliam exterius— literally “If you know the whole [B]ible outwardly”—for outwardly the Flemish is van buiten that in local Flemish idiom means by heart! A similar English idiom is “out and out” that also can mean “thoroughly” or “from the heart.”

j. Here we first encounter a strong, consistent theme of the Devout: that in faith, a strong affective experience is more highly valued than intellectual comprehension, and without practical application, theological propositions are useless.

(I have marked lines that are rhymed in the original Latin text using the following symbols: Ω, §, √, Σ, ∫, ß, π, ∞, ¶, †, ∂, ƒ, Δ, ≈ and μ.)

THOMAS KEMPISaOf The Imitation of Christb

1OF THE IMITATION OF CHRIST AND DISREGARD FOR ALL THE FOOLISHNESS OF THE WORLD

“Whoever follows me does not walk in darkness,”

says the Lord.c

These are the words of Christ, by which we are told Δ

how far we are to imitate his life and character Δ

if we wish to be truly illuminated √

and freed from all blindness of heart. √

Therefore, above all else our commitment

is to reflect on the life of Jesus. √

The teaching of Christ surpasses all teaching of the saints,d

and whoever has his spirit

will find the hidden manna.e

But it happens that many, from hearing the Gospels over and over,

[feel little yearning,

because they do not have the spirit of Christ.f

On the other hand, if one wants fully and sensiblyg to understand the words of Christ,

it is necessary to strive to conform all one's life to Christ's.

What advantage is there to dispute loftily about the Trinity,

if, in the absence of humility, you displeaseh that Trinity?

Truly noble words do not make one holy and just, Ω

but it is virtuous lives that make one dear to God. Ω

I choose rather to feel remorse ∫

than to understand the definition of it. ∫

If you know the whole Bible by heart,i and the sayings of all the

[philosophers,

what advantage is all of that without love and grace?j

a. Ecclesiastes 1:2—“Vanity of vanities,” said Ecclesiastes, “vanity of vanities, and all is vanity.”

b. Deuteronomy 6:13—You shall fear the LORD your God; and shall serve him only, and you shall swear by his name.”

c. Thomas's greatest enemies are “the flesh” “the world” and “the self”—to a degree that is often difficult for moderns to accept. It must be remembered that much of his spirituality was an antidote to the lavish and superficial lives of many parish clergy of his day.

d. For futile Thomas has vanitas (vanity) and repeats it six times in a kind of “catalog” or “list” that is a common tool of the author's throughout The Imitation. The word carries the sense of “ineffective” and “conceited.”

e. Galatians 5:16—“I say then, walk in the Spirit, and you shall not fulfill the longings of the flesh.”

f. This and the preceding five lines are found in the 1441 autograph manuscript but are often omitted in later versions. It has been my intention to be faithful to that original manuscript—even when it contains matter that seems awkward or brash or with which I may not have much personal sympathy.

g. Ecclesiastes 1:8—“All things are hard; man cannot explain them by word; the eye is not satisfied with seeing, nor the ear filled with hearing.”

COMMENTS ON CHAPTER 2

h. “All people by their nature desire knowledge” (Aristotle; Metaphysics, Lbr. I, c.1 and St. Thomas Aquinas; Ethicorum 7:13–14). We note that the author knows classical Scholastic theology even though he clearly prefers the fervent and practical (possibly originally written by the scholar Gerard Groote).

i. “Movements of the heavens” refers to astrological charting of the stars. Even medieval churches were decorated with zodiac symbols. Such astrological exercises were referred to as “natural philosophy” at the time.

j. 1 Corinthians 13:2—“And if I have prophecy, and should know all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I should have all faith, so that I could remove mountains, but have not charity, I am nothing.”

Vanity of vanities, and all is vanitya

except to love God and to serve for him alone.b

That is the ultimate wisdom:

by disregarding the world to press on to the kingdom of heaven.c

Therefore it is futiled to seek crumbling riches,

and to place one's hope in them.

It is futile to solicit lofty status,

and to raise oneself on high.

It is futile to follow the longings of the flesh,e

and to wish for that which will only bring severe punishment afterward.

It is futile to hope only for a life that is long,

And not care if that life is a good one.

It is futile to expend oneself on the present lonely life,

and not to look forward to what the future holds.f

It is futile to love what is speedily passing away,

And not hasten to that place where eternal joys lie.

Often remind yourself of the saying:

“The eye is never satisfied with what it sees, and the ear is never satisfied with what it hears”g

and try to detach yourself from loving what you can see, Δ

and turn to what you cannot see. Δ

For those who let the senses lead, pollute their conscience. √

And lose the grace of God. √

2OF THE HUMILITY TO KNOW ONESELF

All people by their nature desire knowledge.h Ω

But what good is knowledge without the fear of God? Ω

Better a humble peasant who fears God ∫

Than an arrogant philosopher who neglects his soul while he concentrates

[on the movements of the heavens.i Ω

Whoever knows oneself well, recognizes that he is shameful, ∫

Neither is one pleased by the praises of others.

If I know everything in the world,

and am not in charity,j

what advantage would I find before God, who will judge me based

[on my actions.

a. Although some of the Brothers of the Common Life were highly educated and theologically literate, as a community, they were dedicated to an intellectual simplicity that did not credit or demand exhaustive academic knowledge of theology. Some of the Brothers even had to be taught to read so they could efficiently do the copying of manuscripts—the community's primary source of income.

It is apparent throughout Thomas's own writing (that is addressed primarily to his brother monks and particularly to novices) that he speaks on the basis of his own experience and gives the advice of a veteran. The fervency with which he describes the danger of pitfalls suggests that he knows them only too well. There is no sense of a “holier than thou” attitude that speaks down to his Brethren. In later books, his writing becomes more obviously autobiographical and sometimes brutally self-accusing.

b. One notices echoes of Jesus's saying: “from him who has been given much, much will be required, and from him to whom much has been entrusted, even more will be demanded” (Luke 12:48).

c. Romans 11:20—“Well: because of unbelief they were broken off. On the other hand, you stand by faith, so be not highminded, but fear.”

d. Thomas's Ama nesciri (“Love to be unknown”) was the motto of all the Brothers of the Common Life, and led to literary challenges with this very book, since the first manuscripts of The Imitation were anonymous and unsigned, leaving positive authorship in question. It wasn't until the 1441 autograph manuscript that Thomas made clear claim in his own name to writing (or, at least, copying out) the whole book. (This motto may have been influenced by “Seek to be unknown” from St. Bernard's Third Sermon on Christmas Day.)

e.