8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

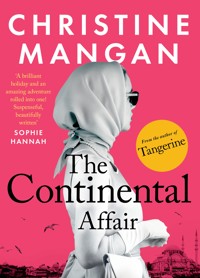

- Herausgeber: Bedford Square Publishers

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

With gorgeous prose, European glamour, and an expansive wanderlust, Christine Mangan's The Continental Affair is a fast-paced, Agatha Christie-esque caper packed full of romance and suspense. 'Reads as if Jean Rhys and Patricia Highsmith collaborated on a script for Alfred Hitchcock; it is an elegant, delirious fever dream of a book.' The Irish Times Meet Henri and Louise. Two strangers, travelling alone, on the train from Belgrade to Istanbul. Except this isn't the first time they have met. It's the 1960s, and Louise is running. From her past in England, from the owners of the money she has stolen―and from Henri, the person who has been sent to collect it. Across the Continent―from Granada to Paris, from Belgrade to Istanbul―Henri follows. He's desperate to leave behind his own troubles and the memories of his past life as a gendarme in Algeria. But Henri soon realises that Louise is no ordinary traveller. As the train hurtles toward its final destination, Henri and Louise must decide what the future will hold―and whether it involves one another. Stylish and atmospheric,* The Continental Affair *takes you on an unforgettable journey through the twisty, glamorous world of 1960s Europe. What reviewers and readers say about Christine Mangan: 'Assured and atmospheric' (Tangerine) Guardian '"Girl on a Train meets The Talented Mr Ripley under the Moroccan sun. Unputdownable' (Tangerine) The Times 'A plot as twisty as the streets of its dazzling Tangier setting' (Tangerine) Daily Mail 'A lush, malice-infused mystery' (Palace of the Drowned) The New York Times 'Atmospheric, twisting, and full of mystery,' (Palace of the Drowned) Refinery29 ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 'I wanted to savour every moment. Perfectly done.' Bertha ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 'Gripping and effortlessly done.' Ruth ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 'I could just feel the heat, picture the beautiful Alhambra and smell the coffees. Stylish.' Mel ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ 'This is the third Christine Mangan book that I've read and it's definitely my favourite.' Charlotte

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

CRITICAL ACCLAIM FOR CHRISTINE MANGAN

‘[Tangerine] The Girl on a Train meets The Talented Mr Ripley under the Moroccan sun. Unputdownable’ – The Times

‘[Tangerine] A plot as twisty as the streets of its dazzling Tangier setting’ – Daily Mail

‘[Palace of the Drowned] A lush, malice-infused mystery’ – The New York Times

‘Atmospheric, twisting, and full of mystery, Palace of the Drowned is a darkly delightful trip of a book’ – Refinery29

‘[Palace of the Drowned] Voluptuously atmospheric and surefooted at every turn’ – Paula McLain

‘[Tangerine] Assured and atmospheric’ – Guardian

‘[Tangerine] A satisfying, juicy thriller… knows all the notes to hit to create lush, sinister atmosphere and to prolong suspense’ – The New York Times

‘[Tangerine] It is an accomplished, ominous, evocative tale of spiralling obsession, skilfully pulled off’ – Alison Flood, Observer

‘[Tangerine] As if Donna Tartt, Gillian Flynn and Patricia Highsmith had collaborated in a screenplay to be filmed by Hitchcock - suspenseful and atmospheric’ – Joyce Carol Oates

‘[Tangerine] Riveting… unputdownable’ – Melissa Katsoulis,The Times

‘[Tangerine] A tightly wound debut that will leave you breathless’ – Evening Standard

To Ron, for always reading the first and last draft – and all the ones in between.

And to the memory of Shadow, whose travels took him many places throughout his lifetime – and even once to the shores of Oran.

1

Henri

‘Pardon me, but I think you’re in my seat.’

Henri looks up at the other passenger, a young woman of twenty-five or so, a single leather satchel held between her hands and an expression of something like suspicion on her face. She has spoken in English, and for a moment he cannot think of the correct response, the words vanishing before they have an opportunity to arrive. It’s a ridiculous reaction, he speaks the language as well as his own. Still, he is taken aback, unprepared. He wishes, suddenly, that it were still early morning, that he were back in the Hotel Metropol, that he had more time.

Henri takes out his own ticket, pretends to study it.

‘You see, you’re supposed to be in the one just there,’ the young woman says, pointing with a gloved hand to the seat opposite him. She is smartly dressed in black trousers and a blouse. Her thin frame is partially obscured by her wool coat, on which hang several large gold buttons that clang together as she leans forward. He has yet to grow accustomed to the sight of women in trousers, but he thinks it suits her, somehow.

‘Of course,’ he responds, conscious that he has yet to reply. ‘My apologies.’

‘Oh good,’ she says, sounding relieved. ‘You speak English.’ Her smile is small and tight, and he notices her left eyetooth is turned, curved in a way that no doubt drove some parent mad when she was a child. This, too, suits her.

He stands, indicates to her leather satchel. ‘May I?’

‘No, thank you, I think I’ll keep it close for now.’ Her hand, he is certain, imperceptibly tightens.

He nods. ‘Bien sûr.’

They sit, then, one across from the other. The air in the compartment is stale. He thinks, watching as she sets her satchel onto the seat beside her, that he can detect the odor of those who came before them. For while standards on such trains had once been revered, all crisp napkins and polished brass, now he can see smudges on the light fixtures, slight tears in the fabric seats. He wonders when the windows were last washed.

Another passenger approaches their compartment, looks in, and turns away.

‘I wonder whether we’ll have it all to ourselves,’ she says, watching the stranger disappear down the corridor.

He thinks she sounds hopeful. ‘If so, I might reclaim my previous seat,’ he replies, then hurries to explain, stumbling over the translated words as he does so. ‘Sitting backward on a train makes me feel strange – not like myself.’

‘Unwell, do you mean?’ she suggests, pushing a strand of hair behind her ear. ‘There’s a saying about that, I think. Something about not dwelling in the past, but looking toward the future.’

‘An English saying?’ he asks. When she only shrugs in response, he presses, ‘But you are from England, n’est-ce pas?’

She nods. ‘London. South of the Thames.’ She pauses, lets her gaze linger. ‘France, I presume?’

‘French,’ he confirms, then after a brief hesitation, he adds, ‘Algeria.’

He sees something then, reflected in her face. He wonders if he is only imagining it, tells himself he must be, for how much can this young woman know about the country he was born in and its internal strife, about Algeria and its fight for independence. She murmurs an affirmation – but no, he realizes he has misunderstood, that she has said something else entirely – Oran. His childhood home, whispered on her lips. He thinks back to a moment, nearly two weeks past.

She must read something on his face then, for she smiles tightly and says, ‘Lucky guess.’ Turning to the window, her breath causing the glass to fog, she continues, ‘Someone told me once that I should visit.’

He finds his voice. ‘Vraiment?’

For a moment – longer than that – he is uncertain whether she will say anything further. There is no indication that she intends to, and he is prepared to sit back and turn away – in disappointment, he thinks – when she looks to him and says: ‘Yes. There’s a particular view, I’m told, from an arched window in the north wall of the Santa Cruz Fort, the best in the entire city. I would have to rent a motorcar – I couldn’t take the people mover, I can’t bear the thought of heights. But I should like to see it, one day. That vast, never-ending blue.’ She pauses, takes a breath. ‘Afterward, I would drive the motorcar out of town, find a café that overlooks the mountains and the sea, and order creponne.’

He can taste it – the sharpness of the lemon, the sweetness of the sugar. It is the taste of his childhood, the smell that still haunts him, even in exile.

She turns to him. ‘It sounds almost too good to be true, n’est-ce pas?’

He is slow to answer. ‘Oui. Particularly in this weather.’ They both turn to the window, where the sun is lost behind the fog and cold of the early morning.

‘I’m Louise, by the way. Louise Barnard.’ She leans across the aisle, closing the distance between them, and holds out her hand. ‘You can call me Lou – everyone does.’

‘Do they?’ he asks, thinking it doesn’t suit her.

She holds his gaze. ‘Yes.’

‘Henri,’ he responds, mirroring her lean, accepting her hand. ‘A pleasure to meet you.’

A moment passes, and eventually they release their grip.

‘Do you mind?’ she asks, indicating the closed window. From her coat pocket, she withdraws a packet of Gitanes. He thinks her hands are trembling, just slightly.

‘No, of course not. Allow me.’ He stands, opens the window, notices she still has not removed her coat. ‘Were you long in Belgrade?’ he asks, sitting down again.

She tilts her head back, blowing the smoke from her cigarette into the air above them.

‘Only a night or two.’

The train conductor interrupts them then. Henri retrieves his ticket and passport from his coat pocket. The conductor looks it over, nods. He turns to the young woman, who in turn opens her small leather satchel, retrieves her ticket and passport, and hands them over. The conductor looks from the passport to the woman, then nods, apparently satisfied. ‘Hvala vam,’ he says and closes the door to the compartment.

They sit back into their seats. The engines rumble and a blast of steam fills the air with its whistle. Neither of them turns to the window, toward the platform, nor do they glance toward the hallway, toward the occasional traveler and passing attendant, luggage in tow.

Instead, they sit and stare at each other.

In the silence that follows, as they wait for the train to depart, Henri does not bring up the last fortnight, does not mention Granada or Paris and the moments they shared there, however small. In turn, she does not speak about what happened in Belgrade. There seems to be an understanding, an unspoken agreement between them, in which they will pretend – at least for now – that the past does not exist. That this particular moment, here, on this particular train, is their first encounter. He does, however, think, as he settles back into his seat, feeling the initial lurch of the train beneath him, that it is a pity – a damn shame, really – that everything about her is a lie.

Before

It was the smell of creponne that he dreamt of most often.

That familiar scent of sugar, caramelizing in the air around him, so strong that he could almost feel the promise of the sharp lemon on his tongue, he could almost believe, in those moments before his mind had fully awoken, that he was back home. That he had only to open his eyes and he would be greeted by a pair of French windows leading out to a filigreed balcony, the strong North African sun filtering through, depending on which way the wind blew, depending on the time of day and the sway of the bougainvillea.

Henri opened his eyes.

Now in another country, another continent, he lingered in bed, allowing himself a moment more to remember. And he did, he remembered it all – motor trips to the beach, to Tipasa, to walk among the Roman ruins, to contemplate what had come before. The smell of diesel, of the sun and sand and olive trees, burned into his senses so that one could not exist without the other. He remembered going to the cinema with friends, was it the Balzac or the Escurial, he could never recall, and the image of the carpet, a deep rouge with a pattern of flowers, forever imprinted on his mind, along with the kernels of popcorn left behind in the wake of the concessions girl. He recalled the place just outside of town, where his father would take them if he was in a particularly good mood. The restaurant perched on a cliff, its whitewashed walls set against the blue of the Mediterranean, which stretched out endlessly, and all around them, and throughout it all, the smell of pine in the air. And the sun, always the sun, shining brightly –

Only it was no longer a sun before him, but an orb of light that burned and blinded, and he was no longer outside, but in a small room, cramped and dirty, entirely dark, save for that one light. He could feel the sweat pooling, dripping down his temples, sliding down his back. The sound of the shouting, screaming – protestors, he knew – just beyond the room, rose and fell, along with something else. Gunshots, he thought, though it was hard to tell, hard to translate anything through the thickness of the walls. And there was a scratching sound, though he couldn’t place exactly where it was coming from. He could hear it, louder than all the other noises, as though whatever it was must be pressed right up against his ear, but when he brushed the side of his face, he felt nothing but air. He looked up, squinting against the bright light.

Two eyes, wide and accusing, stared back at him.

Henri jolted awake, his body drenched in sweat. He opened his eyes and saw the room before him, stark and barren. He must have fallen asleep. It had only been a dream, then, or a nightmare. Oran was hundreds of miles away, and his memories, the time between then and now, over a year already, and growing more still with each passing day.

The dreams, the nightmares – they were all he had left.

Sleep unattainable, Henri pushed the covers aside and decided to begin his walk to the Alhambra, where he was scheduled to be in several hours’ time to collect the money.

He bathed quickly in the tiny sink that sat in the corner of his room. As he wiped away the sweat that had settled, he looked into the mirror, at the reflection staring back, and he thought of those eyes in his nightmare. He had grown used to them – the nightmares, not the haunting eyes – as much as it was possible to grow used to something so uncertain. At least he knew what to expect. A replay of that day, the one that had convinced him, finally, to leave. To uproot his life, once and for all, because the life he had been living was suddenly unrecognizable to him. Sometimes he wondered when it had happened, had known that it was gradual, day by day, month by month, so that he had been able to bend and adapt, to close his eyes to the truth around him. It had been so easy to continue, to pretend – until it was impossible.

It was still early as he left his flat, the sun would not rise for another hour or so, but he decided there was no point in putting it off. He would go to the thirteenth-century palace, and there he would do the job he had been hired to do, by people he could not say no to. Not out of threats or coercion or anything so expected, but because they were blood, which meant a certain responsibility, a certain loyalty that could not be ignored, and because he had been unable to think of a reason to say no when they first asked.

The streets were empty at this hour. Henri crossed the River Darro, the border that flowed around the fortress, without encountering a single other person. The silence suited him. Granada always seemed to be so full of people, so full of life, that he found himself desperate as of late for quiet, for space. He continued on, up the steep path, past houses, his breath becoming hard and labored. He caught the scent of the cypress trees around him. Near the top, he paused. He had never seen the fortress up close before, his only view having been from down below. It felt strange, now, to be on the other side of it. In the meager light of the morning, peering down at the houses, he could almost understand how people fell in love with the city.

In Oran, his mother had spoken little of this place, the city of her birth. But then, she had spoken little of her past in Oran either, including her time spent living with her family in the Jewish enclave oftown – it was good for a time, and then the French came and it was better and then it was much worse – or how she met his father – in town – or their ensuing courtship – we married and I moved into your father’s flat in the French town.

Of her own home country she remembered little, only the faintest trace of orange blossoms in the air – she was little more than a baby when her family had fled Spain – though sometimes, particularly when they sat in the warmth of the kitchen together, she spoke to her son in Spanish, so that he learned enough to understand and speak it on his own. It was there that Henri had learned he had an aunt, his mother’s sister, that they had grown up alongside each other in Oran, but that she had married a Spaniard who had taken her back to their home country. He was not told the man’s name, and when he asked, his mother had only frowned and shaken her head, until eventually he learned not to mention that branch of the family.

When asked of the past, his mother had spoken of France, of his father’s hometown. All her memories outside of Oran set exclusively in Marseille, where they had gone for their honeymoon and spent a week eating bouillabaisse and moules marinière and drinking pastis in bars by the Mediterranean. His father, who was born in the port city, decried it all as filthy and depressing, but his mother described it as others might describe Paris, boasting to neighbors that her family was from Marseille, never noticing the confused expressions that such an admission elicited. What’s wrong with the port here? his father would demand, to which she would cry, It’s not the sea, is it, and from which would always ensue a lively debate on what body of water exactly – Mediterranean or otherwise – the port of Oran overlooked and whether it wasn’t all one and the same.

This, Henri soon understood, was how they spoke of things that were important – by speaking of things that were not.

The only part of her past his mother seemed to carry with her was the making of dafina for Sabbath. All the other religious observations she ignored, but each Friday night she would prepare the potatoes and meat and chickpeas and take it to the local baker, her name etched into the pan so that there would be no mistaking it as anything but her own. Though there was no need, really, as she was among only a few other women baking such dishes in that part of town. In the morning, every Saturday, Henri would walk with her to the baker to fetch the finished dish, which had been baked overnight on low heat, per his mother’s very specific instructions. Despite this, she was never satisfied. The dish was too dry, too cold, the oven must not be working properly, so perhaps they should find another baker.

Henri thought he understood why the perfection of this one dish mattered so greatly to his mother, thought he understood what she was saying in the words she spoke instead.

Henri stopped and looked up at the Alhambra, wondering whether his mother had ever done the same. She had never mentioned it before, this magical, mythical place. Though her silence did not surprise him. It seemed a trait particular to his mother – her innate ability to leave the past behind.

Henri only wished that he had managed to inherit it from her.

The job, the collection of money no doubt earned by illegal means – and that he was now making his way, slowly, but inevitably toward – had come about in the way most things of that nature came about. That is to say, gradually and without any real intent.

Upon arriving in Granada, Henri had rented an apartment near the aunt whom he had never intended to contact – the one his mother had mentioned to him once as a boy and never again – and whom he had sought out in the end, hoping to find something familiar, something that made sense, wanting his days to take on the same shape as they had before in Oran. And it had felt nice to be brought into a family, to be part of something. To not be entirely alone. His aunt had introduced him to the others. His uncle had long since passed, but before he did, there had been children from their union, so that every time Henri went to his aunt’s place it seemed he was introduced to a new son, a new son of a son, or some distantly related relative far removed. Used to the small unit he and his parents had made, Henri found it difficult to remember their names, to know who it was that he was speaking to and where they would fit on a genealogical map.

Soon Sunday lunches at his aunt’s became a common affair, as did visits to the bar around the corner with his cousins, where the cana was cheap and he didn’t feel too guilty about spending what money he had left, hidden under the floorboards in an apartment that depressed him. It had taken some time before his cousins relaxed around him. He had felt it the first time he had gone to his aunt’s – a tightening of the shoulders, a narrowing of the eyes. Henri had sat down at her table and nodded before one of his cousins had raised his eyebrows and asked, ‘Policía?’ It had been a collective question, and so Henri had shaken his head, had raised his voice for anyone interested, and answered, in Spanish, ‘Ya no, not anymore.’ He hadn’t explained further, had let them fill in the rest on their own. Whatever they came up with among themselves, no doubt sprinkled with whatever tidbits his aunt had learned over the years, he was certain there would be an element of truth in it.

Soon, his cousins seemed to relax. A nod here, a buenas noches there. And then eventually, they began to talk with him, about the past, about money, about jobs. About the future. Henri offered little, but it was enough. They understood what he did not tell them – a man had a right to his past, after all – understood what it meant to be a man in a country that was not his own, the idea of returning to where he came from impossible. Eventually, when they mentioned the possibility of a job – nothing too important, just a package to be picked up, taken to another location – he hadn’t hesitated. After all, he was fit for taking orders, his previous life had made certain of that, and so when someone gave him those once again – and not just someone, but family – he accepted.

The jobs were simple and the money easy. And Henri was always in groups of two, sometimes three or four, so it was never down to him entirely. His cousins seemed appreciative of the simplicity with which he conducted each task, the way he did not try to insinuate himself further into their world, though sometimes they tried to insinuate themselves further into his. ‘Come out with us tonight, celebrate,’ he would often hear, after they had retreated from his aunt’s into the local bar.

Henri always thanked his cousin – it was never the same one – telling him that this, gesturing to the bar around him, was all the celebration he could handle, that he would see him next week, at his aunt’s, for lunch. The cousin would laugh, placing his hand on Henri’s shoulder. Once, one of his cousins had said, ‘I like you, you’re smart.’ Henri had assured him that he was not. The man had insisted: ‘That’s how I know you are. Only a smart man would deny such a thing.’ Henri didn’t agree, but he didn’t argue either. Instead, he signaled to the bartender and ordered them another round.

It did not matter to him that these men, cousins and nephews alike, were criminals. After all, the things he had done in Oran were criminal, though sanctioned by law, which made it worse – much worse, he decided – in the end. At least the men he surrounded himself with now were honest about their deceptions. And they were smart as well, so he hadn’t worried at first about being caught, about ending up in some Spanish jail, at which point he was certain they would be quick to forget their association, bloodlines be damned.

But then – something had happened.

There were eyes on them that had not been there before, they said. Two of their own had been arrested in Tarifa, so it was obvious that someone, somewhere was talking. Henri had listened to their new plan: the money left somewhere around the Alhambra, under a bench, in a darkened hallway, just off one of the gardens. The Alhambra was popular among locals and tourists, and Henri had thought it sounded like a bad idea – ridiculous, even – like something out of a hackneyed spy novel. He told his cousins as much, but they had only laughed, had said, ‘Yes, like a spy novel.’ They spoke Spanish, in which Henri pretended to be only moderately proficient, hesitant to let them know just how much he actually understood.

A part of him felt guilty for the pretense, especially where his aunt was concerned. And yet, even before the jobs, on that very first day he had met his mother’s sister, he had remembered the look on his own mother’s face, the deep frown that had settled between her eyebrows at the mention of the woman before him, and he felt himself hold something back, told himself that he was only being smart. Some days he worried that his aunt knew – that she saw the glimmer of understanding in his eyes when he sat around her table for their weekly meal. Henri had taken to looking down at his food instead of at her face, which seemed too close to his mother’s anyhow. He did not know how much she knew of her sons’ business, but when he remembered the way his mother’s face had darkened at the mention of her sister’s new husband, Henri suspected that she knew enough.

The man’s tone that day had indicated there would be no more questions, but Henri had shaken his head in disbelief, ignored the warning, and asked what would happen if someone else came along and took the money before he could get it. He laughed, said it was Spain and nobody rose that early, particularly on a weekend – not even to go to the Alhambra. The man had bought him another cana then and paid Henri half the amount owed, with the other half to be paid upon completion.

‘This one you will do alone,’ his cousin informed him, nodding as he spoke, as if he were still in the process of deciding. ‘Let’s see how this goes, and then we’ll talk.’

‘About?’ Henri asked.

His cousin mentioned the idea of Henri becoming more involved now that he had impressed them. After all, he was family. Henri had smiled and nodded, though his stomach churned. He pushed the money into his pocket and continued to focus on belonging, on becoming a man who had adopted a new country as his own.

A man who fit in, who was built staunchly of the present, who did not live in the past.

Henri had been told to wait on a balcony overlooking the open courtyard.

It would give him the advantage of knowing when the person with the money had arrived, without being seen himself. Once they departed, he would make his way down the stairs and toward the bench where the money would be left. The whole thing would be over in a matter of minutes. Glancing at his watch, he saw that he still had another ten minutes before the money was set to arrive. He bent down and peered out. It was difficultto get a clear view of the space without doing so. The curved windows that ran the length of the balcony all featured low ledges, no doubt built for one to sit rather than stand, as was tradition in Islamic culture. Henri debated, decided he had time, and then lowered himself to the floor.

So this was it, he thought: the oldest garden in the world. He gazed out at the roses and orange trees, at the water fountain, and the canal that ran the length of the garden. An irrigation system, he guessed. The sun had risen by then, casting its golden light across it all. It was beautiful, he knew, and he could appreciate what it was meant to elicit from an onlooker, but all the same, he could not feel it, not in any way that mattered.

It had been this way ever since he first stepped off that boat – before that even, if he were being honest. Now, he spent his days roaming the city for hours at a time, retiring to his room only after the sun had set. In between, he ate and drank, tasting neither. He slept with women but felt empty afterward, crawling out of their beds and leaving before the sun had risen. He was a shadow, he often thought, or a reflection of someone who had once existed. On some nights, he climbed to the roof, looked out at the Alhambra, at the shadow she cast across the city, and waited for it to hit him, that experience he had heard others describe in songs and poems in tribute to the impressive fortress – but there was nothing, just the absence of what should have been.

Still, he did not give up hope. Every day he waited for the forgetting to begin, for his new life to take shape before him and the feeling of being adrift to leave him at last. He woke, he wandered, he slept. He tilted his head to the sun, felt the warmth on his face, but still, he could not smell the orange blossoms on the tree.

It was not that he minded the solitude. He had always been a solitary person, even in childhood, had played mostly with another boy at school, Aadir, the two of them a spitting image of each other until one day they were not, until politics became more important – or, at least, the politics of their parents. They had been friends through sixième, and though chances were they would have drifted away naturally, sometimes Henri wondered. After, it had been his first love, Marianne, around whom he had rearranged his world. Marianne, who had been his friend and then something more, so that her eventual departure had left him shaken, left him rearranging once again, but this time only to allow acquaintances and colleagues, never anything that bordered on real intimacy. He couldn’t quite explain the reason for his detachment, but he found it easier to operate within the world when it was placed at a distance.

At Université d’Alger, Henri had leaned toward history and linguistics, had even considered life as a professor. His parents had been proud of his degree, his mother especially so, but when she turned to him after graduation and said how wonderful it was that he could always read Voltaire in his spare time, he had understood. Afterward, Henri joined the gendarmerie, just as his father had, knowing that it would make his parents proud, which would, in turn, make him content. And it had worked. He had shaped his days around making them happy, had molded his life on being what his mother wanted – which was another version of his father, what she considered to be a good man. A man who came home each night, who drank little, argued less, and did not spend his money on games and drink and women. It pained him, sometimes, to realize that his mother’s definition was so narrow, so limited. But he did his best to do what was expected of him without questioning what he himself expected. Just as he did what the army asked of him, his role in the gendarmerie required another set of instruction, another set of rules to live by, as dictated by others.

And then his parents had died in a motor trip to Madagh Beach. A crash along the coastal road that had stopped traffic for several hours. Henri had seen the aftermath, the broken and steaming bits left behind, the stains on the road. They were gone, and after, Henri found that nothing was the same.

The next day, he had stood outside the Porte du Château-Neuf, leaning up against its façade, the heat against his back, and feeling, for the first time, the constraints of his uniform. He pulled at the collar, wondering whether he had managed to damage it in the wash. But he knew it wasn’t that. It simply did not fit him anymore, if it ever had. Over the years, his occupation had become harder to endure, the événements – that inconsequential word they all used, as if it could hide what was actually happening – now escalating across the country. Algerians were demanding their independence from France, and it was all reaching the point of no return. The événements, they all said, eschewing names like attacks, bombings, riots, war. Even his parents, before they passed, had waved it away with their words, their shrugs, their refusal to recognize that the country they had made a home in for decades no longer wanted them.

Henri had found himself tired, then, of words that were used to avoid saying what needed to be said, that provided distance, a distorted truth, when the truth was plain to everyone. He thought he could see where the French were headed with the Algerians – though it often surprised him to be included as such, having never actually set foot in the country of his nationality – could predict exactly how it would end, and with such astounding clarity that it made him wonder whether everyone else could as well, whether they were simply too stubborn or too frightened to admit it. And then December had come, and the protests had begun, and his need to leave solidified. The things he had witnessed that day, the interrogations that he had participated in during the days after – where before he had been content to do as he was told, to not think of the consequences – they were all that occupied his thoughts. He saw exactly what it was that they were doing, what he himself was doing, and he knew that he could not continue with it any longer – not for another day, not for another hour.

He had stood, his final night, in the Santa Cruz Fort, overlooking Oran. My city, he thought, the city that he had lived in for his entire life. A city that would soon no longer belong to him, or he to it. It was a strange thing, he often mused, to be identified as a Frenchman by the world, when he himself did not. He looked out at the port, at the ocean just beyond. Here was where he belonged. He looked to the old town, where lines of laundry were strung in between the buildings, a tenuous link that held each together, a jumbled mess that made it impossible to pick out where one began and the other ended. He reveled in its chaos, breathing it all in: the smell of baking somewhere in the distance, nutmeg and cloves, fennel and anise, and for him, lemons, always the sharp, bitter scent of lemons. This was real. This was home.

And yet, it no longer was. The Oran of his childhood was now only that: a place that no longer existed, perhaps had never existed at all, anywhere other than within his own memories.

Afterward, he packed up all his things – there wasn’t much, he had lived the spartan life of a soldier – procured a fake passport from one of the many contacts he had made during his time in the gendarmerie, and then boarded a ferry, looking out onto the Mediterranean as it took him away from the only place that he had ever known, a place that marked and defined him. He went to Marseille first, his father’s birthplace. He spent a week in the city, feeling more foreign than a tourist. Eventually, he found himself in Spain, in Granada. In the city his mother could not remember, except for the delicate smell of orange blossoms.

When he had first arrived in the red-ochre city, Henri had walked the remaining walls, found them familiar but different enough, and decided it would do. At least for now. His mother had been Spanish, after all, even if she had not remembered what that meant. In this way, he often thought, they were similar.

He was French and didn’t know what that meant either.

There was a rustle from somewhere below, the sound of pebbles underfoot.

Someone had entered the garden. At the sight of the stranger Henri hesitated, uncertain whether this was the person he was expecting. Something told him it wasn’t. For one thing, the woman standing below him was carrying a suitcase – and while he supposed that could be where the money was hidden, he thought it seemed too obvious, thought that the people they usually dealt with were more clever in their techniques. There was also the way she walked – slowly, as if she were in no hurry, as if she had no real business there. Again, it could be part of the plan, but Henri thought it didn’t seem right, the way she paused at the flowers, at the water fountain, as though she were a tourist, taking in the sights. He frowned, glanced at his watch. It was still early; perhaps this woman had only wandered here by chance. He paused when he saw her face. At the expression that had settled there, one of reverence and awe at her surroundings. He felt himself at once envious of this stranger, of this person he had never met.

Henri averted his gaze, tired of the emptiness that he carried inside him, tired of gazing out at this city, its splendor, and feeling nothing at all. Even these gardens – when he looked at them, he only thought of another garden, hundreds of miles away, of the sloped terraces perched atop another city, its buildings stained not red but white, its length filled with roses and geraniums, oleander and fig trees, so that even now, here, he could—

A scream ripped through the air.

Henri started, bumping his head against the arched window. He cast his eyes over the garden, over the woman, searching for the source of her pain. When his eyes fell on her, he could see that she was still alone. Bent slightly forward now, hands balled into fists, eyes squeezed shut, the scream emitting from her was raw and guttural, so that all at once, he was reminded of home, of the sound that the local women emitted to show joy or grief or rage, and he wanted nothing more than to clamp his hands over his ears, to close his own eyes at the image, at the memory. Henri had never been able to put into words what it had felt like to leave Oran – a decision that hadn’t felt like a decision at all – and yet here it was, all that grief and anger and inner turmoil reflected in the face of the stranger standing below him. It was uncanny, he thought, like seeing a double of himself, the idea so strange and grotesque that he found himself unable to break his gaze.

The woman looked up toward the balcony.

Henri stepped quickly from the opening, pushing himself against the wall, hoping that she could not see him, that she had not already seen him – but she had, he was certain of it. She had looked up and directly at him and yet – he thought of the sun, of the shadows, and he told himself that it was impossible. She could not have seen him standing there, watching. He slowed his breath, tried to compose himself, knowing it was ridiculous to come undone by such a thing as this.

By the time he looked back, it was already too late.

Only after was he able to make sense of it. How another woman, the one he had been waiting for, must have entered the garden, must have strode down the length of the canal and toward the interior of where he now stood. By the time he returned his gaze to the scene below, the woman was all but gone, just a flash of her leg, a black heel, and the money – the money she was supposed to have placed carefully in the hallway, underneath the bench – somehow fallen to the ground, littering the garden below.

The strangeness of it caught him off guard. He knew what had to be done, knew that the moment called for him to abandon his post at the window, to turn and run down the staircase to retrieve the fallen bills before they had time to float away on the wind, or into the hands of someone else. He did none of these things. Instead, he remained still, his gaze fixedon the woman with the suitcase who had screamed. He felt his breath catch as he took in the look that appeared on her face as she noticed the fallen money – something smart and calculating – and he smiled, despite himself.

He knew that he needed to act, knew that there would be consequences – terrible, far-reaching consequences if he did not retrieve the money – and yet, Henri continued to stand hidden in the shadows of the balcony, watching as she gathered up the money, as she placed the bills into her suitcase. Until she began to walk away from the Alhambra.

He followed her out ofthefortress.

From there, they continued across the city on foot, Henri following her in a halting pattern as she retraced her steps, from one street to the next, sometimes circling back on herself, and leading him to the conclusion that she was not from Granada, for even he knew the streets better than she. All the while he kept telling himself that he would take back the money: when they reached the next block, when they turned the corner, before they came to the next cathedral. He didn’t, though. He only continued walking, continued following until, eventually, they passed the bullfighting stadium that sat on the outskirts of town, and from there arrived at the only place left that made any sense: the bus station.

Inside, Henri followed her, trying to remain inconspicuous, turning his head whenever a guard walked by. She went first to the toilets and then to a bank, where he saw her hand over a few of the bills. He cursed. Now would be the time to stop her, before she could spend any more of the money that he would no doubt be responsible for replacing. He didn’t think a familial connection would earn him much special treatment where matters of money were concerned. From there, he watched as she found a café and ordered a coffee. Henri perched on a stool on the opposite end of the bar, in a position where he could see her, but she could not see him – not that she would have noticed. She seemed unaware of anyone at that moment, her eyes focused intently on the cup she held between her hands.

All this he observed, and yet he did none of the things that he knew he should do, that common sense, that years as a gendarme had conditioned him to – instead, Henri waited until she purchased her ticket, then went to the counter and told the agent that he wanted the same fare as the woman before. The man behind the counter frowned but didn’t question him.

Henri looked down at the bundle of tickets he was handed, at a series of tedious connections that would eventually end in Paris. He didn’t give himself time to think – he headed toward the platform.

The first time the driver stopped for a break, he saw the confusion sweep over her face as she took in the changed landscape.

Prior to this, she had been asleep for several hours. Henri was seated several rows back, and even though he couldn’t see her face, he could tell by the lolling of her head. He had been fighting sleep for a while now himself, the heat of the bus pushing down on him, the hours he had lain awake the night before wearing. When the bus came to a stop, she jolted in her seat, and he along with her.

He stood, stretched, listening to his body groan in protest. He was too old, he thought, for such a journey, though there were several men and women decades beyond his own age who had sat without complaint through the last few hours, who would presumably do so for the hours still ahead. Henri lingered on the bus as long as he could, until he worried he was in danger of drawing attention. He moved toward the exit, head down, though he could not stop himself from glancing as he passed by, from noticing the look that had crossed her face – panic, he thought. He pushed himself forward, told himself not to intervene.

In the café, which sat adjacent to the petrol station, he waited for her to exit the bus. When she finally did, it was with her satchel clasped between her hands with such force that it looked as though she expected someone to pry it from her at any moment. Once inside, she followed the other women to the toilets. He ordered a café from the bartender, dropped a sugar cube in it, and drank, trying not to blanch at the bitterness. Spanish coffee was one of the many things he had struggled to reconcile himself to while in Granada.

When she returned from the toilets, she seemed more confused than before. She moved slowly, as though still laden from her deep sleep. He wondered when she had last had anything to eat, whether she was used to the sun, to the heat of this place. Her pale skin suggested this wasn’t likely the case.

She came to stand at the bar, taking the seat next to him. He inhaled, noticed a small freckle on the side of her neck. Her hand half lifted – for the bartender, he thought – and he noticed the way it trembled slightly. Henri wondered then whether she spoke Spanish, even just a small amount, and if not, whether that accounted for some of the confusion he had seen when the bus driver had stopped. He thought perhaps she had only been asleep for his announcement, but now, he wondered whether it would have mattered.

Henri ordered two ponche from the man behind the bar and pushed one toward her, advising her, in Spanish, to drink. She only looked at him, confused. Not Spanish, then. He tried again in French, and he saw something bloom behind her eyes – an understanding, he realized. He told her to drink, then ordered a bocadillo. He asked her where she was going, how far, and told her to eat as well.

‘You’ll feel better soon,’ he promised.

When she thanked him, he knew she meant it, could see the relief written across her face. He knew, too, that he shouldn’t have done it. He wasn’t there to take care of her. He was there to get the money, to bring her back. He didn’t think she would remember this, her eyes were too glassy for a clear recollection. Still, he knew that he was taking too much of a risk.

Henri felt something shift against him – her leather satchel, he realized. He had not noticed it before, but now he became aware that it half rested on his thigh. He looked down, saw the glare of the zipper just below him.

It would be easy, he thought, to take the satchel now, to instruct her to follow him out of the café and toward the petrol station, where surely there was a mechanic of some sort, an automobile that could be purchased for cheap. They could be back in Granada by night.

Or he could just take the money, leave her to continue on to wherever it was that she was planning to disappear. He didn’t think she would protest, didn’t think she would attempt to claim that he had stolen what belonged to her. It would lead to questions, to possible searches, and something told him that this was the reason she was here, on this dusty autobus, rather than in the comfort of an airplane or train berth. The anonymity was part of her plan. It was also what made her vulnerable in that moment, her mind and body addled by the heat.

There wasn’t much time left to decide, he knew. He lowered one hand, inching it closer to the satchel. It wasn’t too late, things hadn’t gone too far. He was certain there was a telephone somewhere in this town. He could let them know back home when to expect him, that their money was safe. It would all be over before it really began. He could go back to Granada, continue with the life that he had been leading, and this, today, the moment in which he now found himself, would be only a memory, a temporary upset on the road that he found himself on.

His hand rested on the leather bag, his grip tightened—

The bus driver stood up and called out: ‘Atención, pasajeros! The bus leaves in five minutes.’

Henri felt the woman next to him shift, and he withdrew his hand quickly, as though he had been burned. He felt his face flush, certain she had noticed, that she had felt the pressure of his attempt, and so he hastily translated the bus driver’s warning to divert her attention. She only nodded, looking down at the sandwich she had been breaking into small pieces before placing each in her mouth. His own stomach ached, and he wished he had thought to order another.

Henri stood, carefully transferring the weight of her satchel back onto her own lap. The bar had grown too close, too stuffy, and he found himself desperate to be outside.

Back on the bus, Henri frowned when he realized that her own seat was still empty. He turned to look out the window, squinted, but they were parked too far away, the café itself too dim to be able to peer in from this distance.